Abstract

Health reform initiatives have caused disruptive change throughout the US health care system. A key driver of change is the adoption of alternative payment models that apply financial risk on physicians and hospital systems. Success in these value-based payment models requires health care provider and payor organizations to continue developing population-based approaches, including partnerships with community-based organizations that provide services within a community setting. Community-based organizations are positioned to serve as an extension of the care continuum because they provide desired access points to upstream services that address nonclinical factors. Yet many health care providers fail to enter into sustainable contracts with community organizations. This limits their ability to treat patients’ social needs and widens the clinic-to-community gap, both of which must be addressed for success in value-based contracts. Future cross-sector collaboration will require stakeholders to abandon transactional partnership arrangements primarily concerned with referral systems in favor of transformational arrangements that better align partnership aims and more equally distribute ownership in solving for capacity building, evaluation, and sustainability. The following practices are based on the experience of local YMCAs and YMCA of the USA in establishing clinic-to-community partnerships throughout the country that can influence clinical cost and quality measures.

Keywords: sustainable, partnerships, clinic-to-community, value-based care, community-based

‘The US health care system is in the midst of a transition that attempts to pay for outcomes rather than solely the volume of services rendered.’

The Y’s Role in Community Health

The Y’s national footprint and experiences in health care integration efforts across communities gives YMCA of the USA (Y-USA) a unique perspective on the role of community-based organizations (CBOs) in community health. Over the last 10 years, the Y has used its Healthy Living Framework (Figure 1) to inform its involvement in a range of community health activities that include policy, systems, and environmental change interventions as well as the scaling of a portfolio of national, evidence-based health interventions that have been replicated across the Y service areas, in an effort to bridge the clinic-to-community gap.

Figure 1.

The framework that guides the Y’s efforts in community health.

As a result of these efforts, local leaders influenced more than 39,000 changes to support healthy living within their communities—changes that include improving access to healthier foods, modifying the built environment to better support physical activity, and improving healthy food, beverage, and physical activity options in early childhood and afterschool programs, among others. In total, these changes have affected up to 73 million lives.

In addition, the Y has scaled evidence-based, chronic disease prevention and management interventions to play a role in provider efforts to achieve the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim objectives—improving the health of populations, enhancing the experience of care for individuals, and reducing the per capita cost of health care. Each of these interventions have their own background studies (ie, randomized control trials) and are designed to address the needs of distinct groups of people, including cancer survivors, people with hypertension or prediabetes, people with arthritis, families with children who carry excess weight, and people at risk for falls. Through these interventions and with the YMCA’s Diabetes Prevention Program as a focal point, the Y has secured pay-for-performance contracts with health plans across Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and commercial product lines, and participated in a successful Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) “Health Care Innovation Award” with the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation.

These efforts have resulted in change at local and national levels that foster conditions necessary for ongoing collaboration across sectors and between stakeholders to close the clinic-to-community gap. They also inform the expertise on the topic of clinical-community partnerships discussed in this article.

The Role of CBOs in an Evolving Health Care System

The US health care system is in the midst of a transition that attempts to pay for outcomes rather than solely the volume of services rendered. According to the Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network (HCP LAN), in 2017, 34% of US health care payments representing approximately 226.3 million Americans and 77% of the covered population flowed through alternative payment models (APMs) built on fee-for-service architecture (category 3) or population-based payment (category 4) models. Category 3 and 4 payments are the most advanced payment categories in HCP LAN’s APM Framework.1 Additional data indicate that the proportion of health plan business aligned with fee-for-service continues to decline, albeit slowly and not always in a linear trajectory, while the proportion aligned with categories 3 and 4 payment models is predicted to increase.2,3 There is variation in the pace at which organizations assume downside risk based on their size and experience,4 as well as slow movement to translate these value-based payments into physician compensation,5 but the prevailing winds indicate that the shift toward value-based payment continues to gain momentum.

One of the APMs that has proliferated the most since the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 2010 is Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs). In the past 5 years, the number of ACOs across payors and the corresponding covered lives has more than doubled, with approximately 440 ACOs covering almost 15 million lives at the beginning of 2013 to just over 1000 ACOs covering 32.7 million lives at the end of 2018.6 Physician participation in ACOs has steadily increased in the past 3 to 5 years as well, and perhaps not surprisingly, physicians in practices that participate in ACOs report lower proportions of their revenue coming from fee-for-service reimbursement than physicians not participating.7

The aforementioned data reinforce the notion that future viability as a physician is increasingly tied to success in value-based payment models. Yet, physician offices face challenges in executing these complex models. For example, success in value-based payment models often requires risk scoring and stratification capabilities in order to link target populations to interventions based on risk.

Even if an organization’s population health management systems are advanced, there is often a part of a patient’s home and community life that clinicians have trouble reaching and influencing. This is comprised of the behavioral, social and economic, and physical environment factors that are nonclinical and which account for approximately 80% of health outcomes.8 Understanding this has led to an increased focus on the impact that individual, health-related social needs and structural, social determinants of health have on lifestyle choices and health outcomes.

Fortunately, CBOs are uniquely positioned to fill in the gaps and serve as an extension of the care continuum. They provide desired access points to upstream services that address health-related social needs. This unique role in the community positions CBOs to partner with provider and payor organizations to address the nonclinical factors affecting health outcomes.

However, despite the clear role that CBOs can play in addressing lifestyle changes, many health care organizations fail to enter into sustainable contracts with organizations in the community. In order to move toward sustainable partnerships that result in improved community health, most collaborating provider, payor, and social service organizations must reimagine what partnerships look like.

The next sections outline emerging clinic-to-community partnership development practices from the field and some examples of those practices coming to life.

Learnings From the Field

Moving Beyond Transactional Relationships

Clinic-to-community partnership arrangements have historically been transactional in nature. Oftentimes, the primary problem being solved for, and therefore focus of the partnership, is establishing enhanced referral systems to community services to increase patient access points. Establishing referral systems is undoubtedly a critical step in increasing awareness and utilization of services, but when this is the primary focus, the downstream impacts to the partnership are detrimental. This type of relationship often transpires because of community-based, grant-funded projects that require a target volume of individuals to be served. To fulfill grant deliverables, CBOs feel pressured to detail medical practices with the hopes of increasing referrals. This results in a transactional relationship between CBOs and their referring partners that misses opportunities to understand what each organization intends to accomplish through the collaboration. Without this shared understanding, partners are limited in their ability to establish shared and mutually beneficial goals that integrate into a formalized agreement.

In addition to over-focusing on referrals at the risk of a holistic partnership, collaborating organizations have also historically not addressed the unbalanced power dynamics that exist at partnership tables and therefore limit the potential for success. Though collaborating organizations may be working toward solving for the same health-related issue (ie, food insecurity among patients), it is ultimately the CBOs that are asked to integrate into the health care paradigm in order to lower costs and improve quality. Yet, CBOs have limited resources to support new technology or operational systems because the social service sector relies heavily on unpredictable funding sources to sustain interventions. CBOs also often have limited knowledge of a health care landscape that emphasizes closing gaps in care to optimize Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures and operationalizing Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) policies and procedures. As a result, they fail to articulate a comprehensive value proposition to providers that aligns with their business imperatives. This allows for cross-sector integration to occur just enough to increase some access points, but the dynamics relegate the relationship to being very transactional and partners collectively leaving value on the table (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinic-to-community partnerships whose primary aim is establishing referral systems.

Moving Toward Transformational Relationships

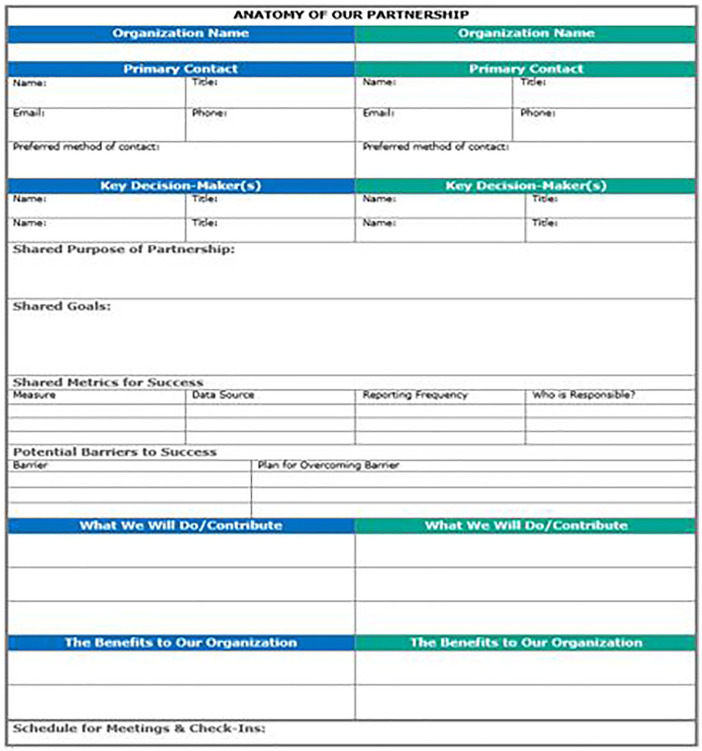

Transactional partnership arrangements can be overcome by taking a more comprehensive approach to the partnership. Rather than viewing the establishment of a formal referral system as the singular goal or end game, referrals should be one step in a larger process. Partners should discuss and formalize shared partnership aims early in the planning process. They should clarify roles and distribute responsibilities across stakeholders. This can be assisted by utilizing a partnership anatomy document like the Y uses (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

A partnership anatomy worksheet helps align stakeholder interests.

Partners should also co–problem solve for challenges related to sustainability, capacity building, technology, evaluation, and the cultural and linguistic knowledge gaps that exist between organizations in order to position the partnership for success. When these topics are discussed during partnership development phases, it encourages collaborating organizations to examine the unique assets they bring to the relationship and how they can be leveraged. For instance, health care and community organizations have different but important abilities to measure and evaluate the success of an intervention. The CBO is likely able to measure participation, short-term health status indicators (ie, up to 1 year), and self-reported quality of life indicators from participants in the intervention. Conversely, a health care provider and/or payor organization has greater ability to measure health care utilization, costs and cost avoidance, and long-term health status indicators than a CBO does. Using all available assets inherently requires greater ownership from all organizations and results in a more balanced power dynamic.

The above-mentioned scenario is just one example of many challenges that confront stakeholders on the ground. There is no single solution to these common challenges, but rather a variety of alternatives that will need to be explored based on the local contexts in which the partnership comes to fruition. However, some challenges that often arise and potential solutions are briefly described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Navigating Common CBO Challenges to Partnership.

| Challenge | Solution |

|---|---|

| CBOs historically lack the organizational knowledge, experience, and resources required to be HIPAA compliant. | Acknowledge that in order for CBOs to play a meaningful role in the care continuum, they may need to increase their organizational understanding and enforcement of HIPAA policies and procedures. Provider and payor organizations have long-standing experience in this subject matter and can potentially play a role in building the capacity of their community partners. |

| Up-front investments in technology, training, and personnel can be too costly for CBOs in order to be ready to partner. | Partners can collectively pursue funds made available through community benefits or other sources to cover these initial costs. These funds should be viewed as seed funding to cover initial costs that decrease the time needed to begin delivering services, producing outcomes, and tapping into a different revenue model that partners have collectively identified for long-term sustainability. |

| CBOs rely on unpredictable sources of funding yet are being asked to establish referral systems that allow them to serve more individuals, which increases their costs. | Partners discuss a sustainability model early in partnership development conversations. This may include a combination of payment models that mimic risk-bearing payment models used in health care and therefore align risk among organizations, but CBOs should be granted glide paths to move down that risk continuum similar to health care provider organizations. |

Abbreviations: CBO, community-based organization; HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

A partnership that can address these topics and others early in planning stages is more likely to move down a pathway that better aligns stakeholders around shared expectations and roles, and one which does not view referrals as the end game. Partners should collaboratively plan for other critical aspects, such as establishing (1) the CBO as a preferred provider of the service, (2) a sustainability plan, and (3) shared responsibility in ongoing evaluation of the intervention and partnership. By embracing these steps, the relationship has moved from transactional to transformational (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Clinic-to-community partnerships whose aims are more holistic than referral systems.

Examples From the Field

The vignettes in Tables 2 and 3 share characteristics of clinic-to-community partnerships that are at various degrees of planning and implementation. The names of the Y’s and their local partners have been de-identified.

Table 2.

Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) and Y Implement a Wellness Program.

| Overview: A Y and a local FQHC implement an 8-week, evidence-informed wellness program that helps participants adopt person-centered goals related to healthy eating, physical activity, and overall wellness. |

| Roles: Staff operate at the top of their license by involving medical assistants, community health workers, and Y health coaches, in addition to oversight from a primary care physician (PCP). Each participant is provided a Y health coach and given up to 3 personalized coaching sessions. |

| Alignment with quality measures: The FQHC’s Uniform Data Set measures potentially affected by the program include the following: percentage of enabling services; percentage of adult medical patients age 18 and older with body mass index screening and follow-up; percentage of patients with hypertension whose blood pressure is controlled; and percentage of diabetic patients with poorly controlled hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). In addition, the state Medicaid program has moved toward value-based payment models, which has resulted in the FQHC having significant business in risk-bearing contracts. |

| Evaluation: Partners share responsibility for measuring the following: labs (HbA1c, total cholesterol, LDL [low-density lipoprotein], HDL [high-density lipoprotein], triglycerides); biometrics and vitals (weight, waist circumference, blood pressure, respiration); PHQ-9; weekly self-evaluations; coaching notes for documentation; person-centered plans; and participant-reported evaluations. |

| Pathway to sustainability: Billable, shared medical appointments are conducted with groups that meet weekly at the Y for education and facilitated discussions; biometrics and vitals during weeks the PCP is present; self-reporting on achievements and barriers; community building activities; and brief coaching and resource navigation. |

| Future opportunities: Work toward interoperable electronic communication between partners to further streamline data collection and sharing; leverage electronic tools such as clinical patient registries to evaluate population health metrics; continue iterating program model to produce optimal outcomes and sustainability. |

Table 3.

Y and Children’s Hospital Collaborate on a Childhood Obesity Program.

| Overview: After participating in a pilot program to evaluate several potential community interventions, the Y is selected by the hospital as the preferred provider of a community-based, childhood obesity intervention. |

| Roles: Trained Y staff deliver a 25-session program that engages a child and adult as a pair so that, together, they can understand how the environment and other factors influence choices that lead to a healthy weight. A baseline and follow-up clinical evaluation is conducted by the patient’s provider pre- and post-program. |

| Alignment with quality measures: HEDIS (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) measures potentially affected by the program include: percentage of children and adolescents 3-17 years of age who had an outpatient visit with a PCP (primary care physician) or OB/GYN during the measurement year and had evidence of body mass index percentile documentation, counseling for nutrition, and counseling for physical activity. The state Medicaid program has also started shifting toward pay-for-performance quality measure targets in its contracts with Managed Care Organizations. |

| Evaluation: Partners have agreed to jointly evaluate program and health care indicators. The Y will track height, weight, and attendance and the clinical partner is still determining which health status and utilization indicators to measure. |

| Pathway to sustainability: The partnering organizations reshaped their view of sustainability from establishing a referral pathway—the original intent of the pilot conducted by the hospital—to discussing referral pathways, shared evaluation, and sustainability. As a result, the hospital helped secure seed funding from a local payor to fund several initial cohorts while the partners continue garnering buy-in from key administrative and clinical decision makers for a shared medical appointment model. |

| Future opportunities: Partners will look to secure support for their long-term sustainability model and begin testing workflows for it while seed funding is still available. With this approach, they will be ready to transition from grant funding to a longer-term sustainability plan. |

Conclusion

The momentum within the health care sector around solving for patient’s nonclinical needs is unlike any in recent times. Health care provider organizations are responding by increasing their competencies in community needs and capabilities in deploying effective population health management strategies because they are both necessary ingredients for succeeding in value-based contracts.

In some cases, they are enhancing their data management strategy to more robustly source, combine, and evaluate health care data from disparate sources such as clinical registries, claims data, or electronic medical record documentation. In other cases, the focus may be on increasing care management and coordination services for patients. Either way, the goal is to stratify patient populations based on risk factors and then connect them to interventions that address their unmet needs.

Inevitably, this leads health care provider organizations to ask themselves whether they need to build an intervention, buy an intervention, or take a hybrid approach to address unmet needs among a subpopulation of patients. Yet, the challenge inherent in addressing social needs forces health care institutions to recognize that community partners must be engaged for strategies that require a “buy it” rather than a “build it” from within approach.

Fortunately, the momentum behind this issue brings a wealth of diverse stakeholders and influx of new resources to partnership tables to solve for these nonclinical factors. Organizations should be cautious, however, in ensuring that the influx of new resources is not merely solving for past barriers to establishing or optimizing referral systems, such as a lack of technology, data analytics, or interoperability. Solving solely for improving referral systems will recycle and perpetuate past shortcomings in clinic-to-community partnerships.

Instead, partners should first work toward understanding and addressing the underlying dynamics present in collaborations. This will enable conversations to take place that focus on establishing shared objectives, solving for gaps in capacity, speaking the same “language,” and sharing ownership for evaluation and sustainability. These are tough conversations to have because they often take circuitous paths and are typically not a primary job responsibility. They require existing and newly collaborating stakeholders to have an openness to approach discussions differently; CBOs can do just as much work to enhance their capacity and learn alongside their clinical partners as health care providers can do to develop sustainable relationships with community organizations. However, addressing the underlying dynamics is a necessary adjustment in order to solve for challenges that transcend sectors. With more stakeholders at clinic-to-community and other partnership tables than ever before, it is also a realistic adjustment to expect to occur.

Acknowledgments

I gratefully acknowledge the collaborative spirit of local YMCA’s and their health care partners throughout the country, particularly YMCA’s that participated in Y-USA’s Clinical Integration Demonstration Cohorts funded by the generous support of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation from 2016 to 2018. I also thank the following individuals for their contributions related to the article: Heather Hodge, MEd, and Katherine H. Hohman, MPH.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: The study was approved by the institutional review board at the University of South Carolina.

Informed Consent: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Trial Registration: Not applicable, because this article does not contain any clinical trials.

References

- 1. Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network. APM measurement: progress of alternative payment models: 2019. methodology and results report. http://hcp-lan.org/workproducts/apm-methodology-2019.pdf. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 2. Catalyst for Payment Reform. 2018. National Scorecard on commercial payment reform. https://www.catalyze.org/product/2018-national-scorecard/. Accessed November 10, 2019.

- 3. Change Healthcare. Finding the value in value-based care: the state of value-based care in 2018. 2018. 2018VBCstudy.com. Accessed November 10, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muhlestein D, Bleser WK, Saunders RS, Richards R, Singletary E, McClellan MB. Spread of ACOs and value-based payment models in 2019: gauging the impact of pathways to success. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20191020.962600/full/. Published October 21, 2019. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 5. Gordon R, Burrill S, Chang C. Volume-to value-based care: physicians are willing to manage cost but lack data and tools findings from the Deloitte 2018. Survey of US Physicians. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/4628_Volume-to-value-based-care/DI_Volume-to-value-based-care.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2019.

- 6. Muhlestein D, Saunders R, Richards R, Mcclellan MB. Recent progress in the value journey: growth of ACOs and value-based payment models in 2018. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20180810.481968/full/. Accessed February 27, 2020.

- 7. Rama A. Policy Research Perspectives: payment and delivery in 2018: participation in medical homes and accountable care organizations on the rise while fee-for-service revenue remains stable. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2019-09/prp-care-delivery-payment-models-2018.pdf. Accessed October 10, 2019.

- 8. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. 2014. Rankings: key findings report. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/2014%20County%20Health%20Rankings%20Key%20Findings.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2019.