Abstract

Introduction:

Recently, participation in clinical global health rotations has significantly increased among graduate medical education (GME) trainees. Despite the many benefits these experiences provide, many ethical challenges exist. Well-intentioned partnerships and participants often encounter personal and professional dilemmas related to safety, social responsibility, and accountability. We designed a curriculum to provide trainees of all specialties with a comprehensive educational program aimed at delivering culturally mindful and ethically responsible clinical care in resource-constrained settings.

Methods:

The McGaw Global Health Clinical Scholars Program (GHCS) at Northwestern University offers a 2-year curriculum for selected GME trainees across specialties interested in global health. Each trainee must complete the following components: core lectures, peer journal club, specialty-specific lectures, a mentorship agreement, ethics and skill-based simulations, a global health field experience, a poster presentation, and a mentored scholarly project.

Results:

Since 2014, 84 trainees from 13 specialties have participated in the program with 50 current trainees and 39 graduates. Twenty-five trainees completed exit surveys, of which 95% would recommend this program to other trainees and 84% felt more prepared to deliver global health care. In addition, 78% reported career plans that included global health and/or work with underserved populations. Trainees described “acceptance of differences and respect for those differences” and “understanding sustainability” as learning points from the program.

Discussion:

Providing a comprehensive global health education program across specialties can be feasible and effective. GME trainees who participated in this program report feeling both more prepared for clinical experiences and more likely to serve the underserved anywhere.

Keywords: global health, medical education, ethics

Introduction

Over the last few decades, American medical trainees and professionals at varying levels of clinical training have expressed a growing interest in global health.1 With increasing international travel and globalization, physicians and those in training have acknowledged a need for better understanding of global health systems, the global burden of disease and ways to address health disparities between systems. Academic institutions have responded to this interest and a large majority of medical schools and GME programs across the United States offer trainees opportunities to travel abroad and participate in short term experiences in global health (STEGH) and more and more programs include some form of global health teaching or training along with these rotations.2 Furthermore, an increasing amount of American academic institutions have partnered with foreign institutions to provide educational exchanges and funding.3,4

An AAMC survey in 2010 showed that 30.2% of graduating medical students have participated in these activities.1 Upon entering residency, numerous studies have shown that global health interest remains high and often influences trainees’ selection of a training program.5 Offerings of global health education during residency and fellowship have historically been available to those training in primary care specialties (family medicine, primary care internal medicine, and pediatrics) but are now increasingly available for trainees of all specialties.6 In a survey of ophthalmology residency programs in 2012, 54% of programs reported offering a global health elective.7,8 Additionally, a survey of plastic surgery residency programs in 2015 showed that 64% of programs sponsored resident participation in global health missions.7,9 Despite the growing availability of STEGH opportunities in GME training, trainees continue to voice more and more interest and desire for further and structured programs.2 A 2007 survey of surgical residents revealed that 98% were interested in an international elective and 73% would prioritize this over any other elective.10 In 2010, 91% of surveyed anesthesiology residents reported interest in global health as well as 72% of radiology residents, further showing that interest is persistent and prevalent across specialties.7,11,12

When participating in an international elective, trainees often encounter a new culture and medical system and are exposed to different and often unfamiliar methods of diagnosis, treatment, and interactions with patients and caregivers. The benefits of these international electives have been well-established and reported by trainees themselves.13 Trainee STEGH participants have noted improved confidence in clinical skills, less dependence on technology, an increased awareness of cost, and an appreciation of public health and preventative medicine.14 These benefits are thought to improve not only the individual trainee but the U.S. health system as a whole given that those who participate in international rotations are more likely to choose primary care specialties, work with underserved populations and opt for public health degrees.2,13

Despite these many benefits, many concerns have been raised about the risks of undertaking global health rotations without the preparation one would typically have when approaching a novel clinical setting. Without thoughtful planning and education, global health rotations can lead to ethical issues that negatively affect the host institution, local health professionals and trainees, the rotating trainee, patients as well as local communities.15 Unbalanced partnerships can lead to undue burden on the local system and raise concerns about exploitation and sustainability.16 Visiting trainees may feel compelled or be asked to practice outside their scope of practice or with minimal supervision causing significant harm to patients, who may be unaware of their individual expertise particularly in a new context.17 Returning trainees have also reported feeling inadequately prepared to handle the ethical dilemmas encountered during these experiences.18 Numerous initiatives have been launched to respond to these concerns and establish consensus on ethical guidelines for global health partnerships and rotations. Nearly a decade ago, The Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT) collectively agreed upon the key components of global health partnerships including: the importance of structured programs between partners, reciprocal and mutual benefit, comprehensive accounting of cost, the value of long term partnerships, selection of suitable trainees, adequate mentorship and supervision of trainees, preparation of trainees, trainee safety, appropriate trainee attitudes and behaviors.19 Since then global health competencies have been proposed as well as multiple best practice guidelines for both the structure of STEGH at the institutional level and for individual trainees.20-23 Multiple individual institutions have also created pre-departure trainings that are open to other institutions and better prepare trainees for these experiences including the American Medical Student Association, edX through Boston University, Unite for Sight, Child Family Health International, and Aperian Global.24-28

In addition to addressing these ethical challenges, creating and operationalizing a global health training program for graduate medical trainees can be a truly formidable task. GME residents and fellows have substantial workloads with significant time constraints and mandatory program requirements to complete training, which are particularly applicable to those in the surgical specialties (Obstetrics and Gynecology, Anesthesia, Surgery, and surgical subspecialties).29 Furthermore, given the constant acquisition of new skills and evolving independence, defining scope of practice during global health rotations is a common ethical dilemma faced by GME residents and fellows. Finally, the individualized objectives, needs and partnerships across specialties vary significantly and can lead to global health education within an institution feeling disjointed. At our institution, the Center for Global Health which is now the Institute for Global Health and will be referred to as IGH, already existed and offered support to global health faculty and interested GME trainees looking for mentorship and international rotations. However, there was not a structured path for GME trainees to designate themselves as interested in global health, obtain formalized mentorship and education around these rotations or be exposed to intentional opportunities for collaboration and careers in global health. Thus, we designed and implemented a global health clinical scholars program (GHCS) that would fill these many needs and current gaps in standard training. We combine a standardized educational curriculum for GME residents and fellows across all specialties to prioritizes institutional unity, collaboration and consensus in our approach to global health education with individualized specialty-specific teaching and mentorship for trainees to be successful within their interest area. The global health rotations themselves are offered through their training departments however our program aims to create an educational scaffolding around these STEGHs. The core curriculum is focused on teaching trainees how to provide culturally respectful and ethically responsible care in resource constrained settings.

Methods

Curriculum development

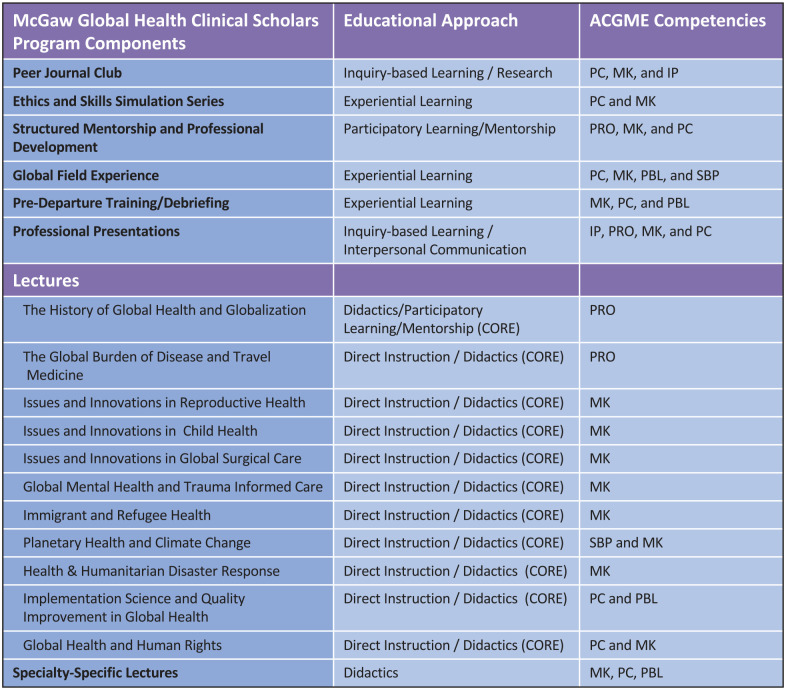

We used a modified Kern’s methodology to develop our curriculum and focused on identifying the problem/general needs assessment, targeted needs assessment, goals and objectives, educational strategies, implementation and evaluation, and feedback.20 As an initial needs assessment, internal medicine residents participated in a 2-part survey that asked who would participate if a global health opportunity were available. Of 51 participants, 33% responded yes and 31% responded maybe. We also asked how important they feel global health opportunities are to residency applicants, of which more than 60% responded with moderately or very important. After establishing this general trainee interest, the IGH faculty drafted a preliminary curriculum and conducted 2 rounds of focus group interviews. The curriculum was created based on seminal training texts,21,22 PubMed literature searches, ACGME competencies, and input from professional networks such as the Consortium of Universities for Global Health (CUGH). The first group was a meeting comprised of interested program directors, leaders of GME and IGH faculty who revised the initial draft. Given the many stakeholders involved in creating a curriculum that spans all specialties, institutional alignment, and support for the program was imperative. A second targeted needs assessment was completed and recommendations from a second focus group was used to finalize the curriculum. We ensured that global health competencies were in alignment with GME competencies for each specialty (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Alignment of global health competencies with GME competencies for the GHCS program.

Abbreviations: GHCS, Global Health Clinical Scholars Program; IP, interpersonal skills; MK, medical knowledge; PBL, practice based learning; PC, patient care; PRO, professionalism; SBP, systems based practice.

Program structure

A 2 year program is available for all graduate medical trainees (residents and fellows of all specialties) interested in global health whose program partners with the GHCS. Our program staff is composed of a core faculty including a program director (PD), assistant program director (APD), and program assistant. Curriculum development, arrangement, and supervision of partnerships with each specialty, provision of educational opportunities, and general scheduling are the primary roles of this faculty and the program itself. The education program assistant from IGH supports the McGaw GHCS as part of her portfolio in program administration.

A formal partnership agreement with the trainee’s department and our program is required as there are many support and scheduling roles needed to participate. Each individual training program agrees to provide specific lectures, scheduling support including time for the field experience, simulation instruction, and provision of a faculty mentor within the trainees’ department. Once a trainee expresses interest in the program, a formal meeting is held with their program director and potential specialty-specific mentors in order to determine the feasibility of the partnership. Programs are added as partners on a rolling basis. Once part of the program, specialty specific mentors meet together with core faculty every 3 months to discuss progress of mentees, delineation of tasks, and ideas for program change and improvements. The PD receives support from Northwestern GME, the APD and faculty mentors are supported by the Global Health Initiative, an internal global health philanthropic fund.

Applicant selection

A program application and recruitment materials (see Appendix 1) are now sent out to all GME trainees (until 2018, these applications were sent out at the discretion of the residency or fellowship program director). Interested GME trainees complete an application which includes a statement of interest and a formal recommendation from their program director (see Appendix 2). Information sessions for all interested trainees are provided by our program director and for individual programs upon request.

Program components

Once admitted to the program, all trainees are provided with a copy of the following educational objectives which are continually emphasized throughout the duration of the program.

Educational objectives

Describe the global burden of disease and demonstrate understanding of epidemiologic tools and methods

Understand health implications of travel, migration and trade

Recognize the major determinants of health

Demonstrate a basic understanding of the relationship between health and human rights

Demonstrate high standards of ethical conduct and quality in global healthcare

Explain the role of community-engagement strategies in capacity strengthening

Demonstrate cultural humility and cross culturally effective support to patients

Develop strategies for ethical practice in unfamiliar and resource-constrained settings

Develop a global health focused scholarly work and peer teaching skills

Trainees must then complete the following curricular requirements in order to graduate from the global health scholars program (see Appendix 3). Trainees have 2 years to complete all requirements based on individual schedules though we allow trainees with longer clinical programs, especially those in surgical specialties, to use additional years to complete the program.

1. Orientation: Requirement: Attendance

Once admitted to the program, all trainees must attend orientation. This time serves as a general introduction to the program and curricular requirements and an opportunity to meet with trainees in other specialties.

2. Core Lectures: Requirement: Attend 9/11 lectures

These lectures serve to provide a basic foundation in global health and tend to cover broader topics that are pertinent to all specialties (see Figure 1 for complete list of core lectures).

3. Specialty-Specific Lectures: Requirement: Attend 5/6 lectures

These lectures are organized by the global health mentor and are intended to provide their trainees with global health knowledge specific to their specialty. Of note, all trainees are invited to each other’s specialty-specific lecture series as there are often cross over areas of interest (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of specialty-specific lecture topics given in GHCS.

| Specialty | Lecture topics |

|---|---|

| Internal medicine | • Fever in the returning traveler • Emerging global diseases • Advocacy/activism and tobacco cessation • Oncology care in low-resource settings |

| Neurology | • Global burden of stroke • Sleep disorders in refugees |

| OBGYN | • Community health workers’ role in obstetric care • Disproportionate burden of cervical cancer and challenges of treatment in sub-Saharan Africa • HIV current strategies for obstetric patients |

| Family medicine | • Immigrant and refugee rights • Intimate partner violence in Chicago’s immigrant communities • Disability process and rights • Global surgical system strengthening: from evidence to implementation |

| Pediatrics | • Immigration status as a social determinant of health • Incorporating global health into your career as a pediatrician • World refugee day: trauma-informed care |

Copyright: Northwestern McGaw Global Health Clinical Scholars Program.

4. Peer Journal Club: Requirement: Participation and Mandatory Attendance

In order to encourage trainees to remain updated on emerging issues in global health and to critically appraise global health literature, trainees from each specialty, either as a group or individual, present a journal article relevant to that specialty. Each trainee must discuss the selection and plan for discussion of the chosen article with their global health mentor prior to presentation. On the day of presentation, the trainee should be prepared to discuss key takeaways, strengths and weaknesses, and relevant discussion questions.

5. Structured Mentorship and Professional Development: Requirement: Meetings every 2 to 3 months and more frequently prior to, during and after field experience; fulfillment of mentor-mentee agreement.

Each trainee is paired with a global health mentor who is a faculty member from their home department. Mentors are expected to use their specialized knowledge in both global health and that particular specialty to support, supervise, and mentor each trainee. Each mentor is provided with a set of expectations and responsibilities (see Appendix 4). Mentors meet with trainees before, during and after each field experience, assist with creation of peer journal clubs, and provide career guidance. Each mentor has no more than 3 mentees at one time in order to provide each trainee with a meaningful relationship. Mentors and mentees are required to sign an agreement stating that both have a mutual understanding of what the mentoring relationship will involve and can agree on action items that should take place. All mentors from all programs meet every 3 months in order to review and revise the program and troubleshoot current issues, discuss upcoming lectures or educational products, receive global health education trainings or resources and discuss trainees and their progress toward graduation requirements.

6. Ethics and Skills Simulation Series: Requirement: Attend 3/3 simulations

A detailed description of the Ethics and Skills Simulation Series can be found in Appendix 5 which describes the entire curriculum and contains documents to support implementation.

7. Global Field Experience: Requirement: Participation

Trainees complete a 4 to 6 week experience at an approved field site. Our institution has several global health partnerships and different specialties have partnerships that are supervised and arranged by their department at international clinical training sites. Our trainees typically choose a specialty-specific site where there is an existing partnership that is approved by their program director, global health mentor, and finally the GME leadership. Each partnership varies in terms of Memoranda of Understanding, trainee activities, participation, supervision, and support at the site.

Examples of Active International Partnerships include:

Internal Medicine: Hillside Health Care Clinic, Belize; Centro Medico Humberto Parra, Bolivia

Family Medicine: Clínica de Familia La Romana, Dominican Republic; Hillside Health Care Clinic, Belize

Anesthesiology: Hospital Materno Dr. Reynaldo Almanzar, Dominican Republic

General Surgery: Bolivia Trauma Initiative, Bolivia

Pediatrics: Bugando Medical Center, Tanzania

8. Pre-departure training and Debrief: Requirement: Participation

Trainees are required to complete all 3 modules of “The Practitioner’s Guide to Global Health” which is a timeline-based course provided by EdX and Boston University as well as Unite for Sight’s module on Ethics in Photography.25,26 The simulation series, particularly the ethics simulation and nearly all of the core lecture series, also comprise essential pre-departure training.

Trainees are also required to meet with their mentors prior to travel in order to reflect on the content of the pre-departure training modules and discuss the trainee specific objectives of the experience. They can opt to communicate with their mentor during their field experience but are required to debrief with their mentors within 2 weeks of their return.30

9. Scholarly Project: Requirement: Participation

Upon returning from their field experience, trainees are required to complete a scholarly project which should demonstrate understanding of a learning objective relevant to their global field experience. This may include any of the following: poster or abstract presentation, opinion piece, clinical reflection essays, peer-reviewed publications, curriculum development or training materials, literature reviews, educational initiatives for health care workers, research (encouraged only from those participating in year-long research fellowships already), and quality improvement initiatives.

10. Professional Presentation: Requirement: Participation

Trainees are asked to present a poster abstract on global health day hosted by the IGH that is relevant to their field experience or global health area of interest. This should also meet one of the aforementioned educational objectives. Trainees have recently presented posters entitled “Seizures in Tuberculous Meningitis in Zambia,” “Birth Tourism: Obstetric and Neonatal Outcomes,” and “Understanding the High Caesarean Section Rate in Egypt: An Exploratory Study.”

11. Optional Exit Survey: An optional exit survey is offered at the end of the program. An IRB exemption was obtained to analyze and report this data.

Results

2014 to 2015 served as our pilot year in which 3 trainees participated in the program. Trainees were from internal medicine, family medicine, and physical medicine and rehabilitation and formal partnerships were formed with these programs. Since our pilot year, the program has grown to a total of 84 trainees and 13 formal partnerships with residency and fellowship programs. As of 2019, 50 trainees are actively participating in our program. New specialties continue to be added each year and now non-primary care specialties make up the majority of our trainees (see Figures 2 and 3). Our trainees have participated in global field experiences with established partner sites as listed above. A few training programs have established new formal partnerships after approval from their program’s and GME leadership. Some trainees are beginning to create local partnerships with underserved communities in the U.S. as well. Our faculty play an advisory role in these final decisions.

Figure 2.

Total participants in GHCS by specialty, 2014 to 2019.

Abbreviation: GHCS, Global Health Clinical Scholars Program.

Figure 3.

Graduates of GHCS by specialty, 2014 to 2019.

Abbreviation: GHCS, Global Health Clinical Scholars Program.

In total, 39 trainees have graduated the program. The 2 trainees who completed all curricular requirements except a field experience received an area of focus designation. There has not been a surgical specialty graduate outside of OBGYN given their longer training programs and propensity to extend participation in the program to fit individualized scheduling needs. Many of our trainees have continued to pursue work with underserved populations both in and outside the United States after graduation. Three trainees have been awarded NIH Fogarty awards, one for cardiovascular health services research and one for paternal roles in OBGYN in Kenya and one for Neurosurgery in Peru (while participating in the program). One of our recently graduated trainees worked as an oncology clinician for Partners in Health in Rwanda. Two are working at federally qualified health centers. One will continue to teach simulation curriculum in Tanzania as part of a faculty appointment and will have a leadership role in global health education at our institution. Many of our trainees are currently pursuing fellowships including additional graduate global health training programs.

In total, 25 exit surveys were completed with 90% agreeing or strongly agreeing when asked if the program added value to training. When asked, if after completing the program, trainees felt more prepared to deliver global health care 84% agree or strongly agree. Eighty percent agree or strongly agree that the program encouraged them to start or continue a career in global health. Ninety-five percent would recommend this program to other trainees. Seventy-five percent will be working with underserved populations, both in and outside the U.S. Trainees reported that, “the combination of didactics, mentorship, resources, and funding provided by the GHCS program unquestionably added to my development as a global health physician-scientist.” Another noted that the program led to “increased awareness of global health, cultural considerations and limitations, resource limited decision making, and provided networking opportunities. The simulation sessions were highly informative and helpful.”

When asked what they learned from the program, one noted, “acceptance of cultural differences and respect for those differences in partnered health decision making” and another said they learned, “ethical considerations, my place in a multinational healthcare team.” In regards to core lectures, some trainees with prior global health experience felt that these were too “basic” for their knowledge base. Other trainees felt that they provided the broad education that they needed.

When asked specifically about their mentors, 96% felt that their mentor met their needs. One commented that “our mentor was always available to us for advice and heavily facilitated our travel and clinical arrangements for our month-long site visit. For our simulation sessions, she was also very helpful and kept us on track and organized. She is an excellent mentor who consistently encouraged us to seek out global health opportunities for our education.” Another wrote “. . .having a scholarly project as part of the requirement made us think more critically about systems improvement and helped make our site visit even more valuable.” Others also noted that “the program allows for interactions with residents and attendings from other specialties who would otherwise potentially never interact with one another.” Another trainee commented, “Had I gone abroad without this program, I would have been unknowingly ill-prepared. The adage ‘you don't know what you don’t know’ comes to mind. I know I will make my share of mistakes in the future while practicing abroad (and stateside) but I will make far less and I believe. . . (do) more good and less harm, because of the global health program.” A few trainees also alluded to the idea of making the program more of a community. One trainee specifically noted, “We do individual debriefing in our program, but I think post-travel discussing what we have done and experienced together would be valuable.” A final and unexpected outcome of creating the global health clinical scholars program was the subsequent development of 3 other scholars programs (bioethics, medical education, and health disparities and equity)31 at our institution using the structure of our program as a template.

Discussion

Given concerns around and needs for safe and ethical STEGHs, many institutions have recognized both a need to better prepare trainees for these experiences and that trainees interested in careers in global health require dedicated education and professional development which are not traditionally offered in most GME programs. Learning objectives, best practices and frameworks have been established to standardize the ethical principles that should guide trainees’ actions during global health rotations. With these in mind, we aimed to create a general curriculum that could be adopted by graduate medical education programs for trainees across all specialties. We have found that this approach can establish a standardized, mindful and safe approach to clinical global health practices by GME trainees, increase collaboration and promote trainee professional development throughout the institution. We were able to deliver a robust educational curriculum incorporating a variety of instructional strategies and using asynchronous curricula from other platforms like EdX, Unite for Sight which helped to expose trainees to a variety of approaches to the material. Experiential and transformative learning were central to our curriculum with both the field experience and simulation.25,26 Our simulation curriculum provides trainees with high-fidelity, safe, experiential learning with structured debriefing in preparation for challenges they may encounter in their field experience. We also came to recognize the immense value in creating an educational home where trainees interested in global health can receive the support to reach their goals.

There were also several challenges that we encountered when implementing this curriculum. Coordinating schedules, lectures, and simulations across specialties can be incredibly difficult. We held global health faculty meetings every 3 months to improve communication and arrange educational activities. Having a designated program assistant to arrange and disseminate logistics, schedules, and educational materials improved efficiency and offered unified support to trainees and program partners. Trainees in our program also reported struggling to attend required curriculum components due to clinical schedules. In fact, we created this program over 2 years (or more for those with longer clinical programs) in order to have a better chance of attending more events. Trainee feedback about the content of the core lectures reflected the diversity of our learners. Given trainees join the program with differing levels of expertise, it can be difficult to meet all trainees’ needs. We are planning to incorporate a more in-depth lecture schedule especially for second year trainees and those with prior global health experience. We have also found that trainees are interested in learning more about career opportunities and are planning a career development series that will illuminate opportunities in global health related to research, clinical care, advocacy, and work with both governmental and non-governmental organizations. In response to trainees requesting that our program provide a deeper sense of community and collaboration, we are planning to incorporate more shared experiences and platforms for group discussion through videos, small groups, and social events.

Other institutions such as Mount Sinai, University of Virginia and Indiana University have formed global health education programs that also focus on collaboration between specialties and have been designated as collaborative interdisciplinary global health tracks (CIGHTs). These programs have further highlighted the strengths of the multidisciplinary approach including shared allocation of global health resources, consensus on global health education, and consistent mentorship regardless of year-to-year trainee interest.32 With similar program components (educational activities, international experience, and mentoring etc.), these curriculums are seemingly differentiated in their educational approach with our focus being on learning global health ethics especially through simulation whereas other programs have emphasized participation in bidirectional educational exchanges and public health courses.32

Although it can be difficult to meet the needs of many different trainees, we have found that creating an educational space for global health trainees and mentors of all specialties is fundamental to a supportive and collaborative learning environment. By establishing a codified set of basic knowledge, attitudes, and professional skills rooted in ethical practice in STEGH, we can begin to prevent unintentional harms, improve patient and trainee safety, support and enable professional development for dedicated trainees and standardize best practices in clinical global health both within our institution and beyond.

Acknowledgments

The study group acknowledges valuable input from Dr. Elizabeth Groothius, Dr. Mamta Swaroop, Dr. Magdy Milad, and Dr. Feyce Peralta as well as staff support from Sara Caudillo and Elizabeth Nicole Christian. We would also like to express a sincere thank you to Northwestern Graduate Medical Education, McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University, and the Global Health Initiative.

Appendix 1

McGaw Global Health Clinical Scholars Program

The McGaw Global Health Clinical Scholars program (GHCS) is a 2-year educational program designed to equip graduate medical education trainees with the knowledge and skills trainees to better understand the global health landscape, challenges and best practices in care delivery in resource-limited settings worldwide.

Applications are due:

Program structure:

GHCS combines the expertise of institutional programs and leaders to provide an interactive, supportive efficient, and valuable learning experience.

Program participants attend monthly didactic sessions focusing on a different core Global Health topic.

The program also offers specialty-specific and peer lectures that are specific to the trainees’ field of expertise. Finally, simulation has been incorporated to teach principles of clinical care and ethics in resource limited settings worldwide.

Key features of the program include:

Approximately 20 to 25 participants which are accepted into the program through a competitive application process

Two year program design

Structured mentorship and a final scholarly project

Pre-departure training and mentorship throughout Global Field Experience

Peer-teaching in both didactic and simulation sessions

Graduation as GHCS once all program criteria are fulfilled

Core Lectures on the first Wednesday of each month from 6:30 to 7:30 pm

Please note:

Attendance at orientation is required and will be held on:

Location:

The application will require you to upload a headshot or recent photo, completed Program Director Recommendation Form, and Statement of Interest.

If you are interested in joining the program, please apply here: https://bit.ly/2qXyQND

If you have questions, comments, or would like to discuss the program further, please email Program Assistant, Institute for Global Health.

Appendix 2

Global Health Clinical Scholars Program

Program Director Recommendation Form

Program summary:

The McGaw Global Health Clinical Scholars Program offers Northwestern University’s McGaw Graduate Medical trainees (residents and fellows) a 2-year program. Curricular requirements include 10 of 12 core lectures, 5 of 6 specialty lectures, participation in a quarterly professional development and journal club, faculty mentorship, web-based training modules, simulation training, contribution to cross residency skill simulation, global health field experience, and production and presentation of a scholarly project.

To be completed by Program Director:

Do you believe the applicant would be able to complete the requirements of this certificate program? What would they contribute to the program?

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

I have reviewed the McGaw Global Health Clinical Scholars program and am familiar with the above applicant applying for admission. This applicant is in good standing with their program and has demonstrated leadership potential. I believe the above applicant would contribute to the Global Health Community and the academic quality of the program. I hereby recommend this applicant for admission.

Name of Program Director recommending applicant: _____

Title: _____________________________

Signature: __________________ Date: __________________

Please return this form to:

Appendix 3

Global Health Clinical Scholars—Program checklist for graduation. Completion rate.

| # | Check Items (double click topics to expand /collapse) |

Descriptions | Checked by (user stamp) | Checked at (time stamp) | Status (double click to change) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Core Lecture Series | ||||

| 1.1 | Orientation | ⎕ | |||

| 1.2 | The History of Global Health & Globalization | ⎕ | |||

| 1.3 | The Global Burden of Disease & Travel Medicine | ⎕ | |||

| 1.4 | Issues & Innovations in Reproductive Health | ⎕ | |||

| 1.5 | Issues & Innovations in Child Health | ⎕ | |||

| 1.6 | Issues and Innovations in Global Surgical Care | ⎕ | |||

| 1.7 | Global Mental Health & Trauma Informed Care | ⎕ | |||

| 1.8 | Immigrant & Refugee Health | ⎕ | |||

| 1.9 | Planetary Health & Climate Change | ⎕ | |||

| 1.10 | Health & Humanitarian Disaster Response | ⎕ | |||

| 1.11 | Implementation Science & Quality Improvement in Global Health | ⎕ | |||

| 1.12 | Global Health & Human Rights | ⎕ | |||

| 2 | Specialty Lecture Series | Name/Date | |||

| 2.1 | Lecture 1 | ⎕ | |||

| 2.2 | Lecture 2 | ⎕ | |||

| 2.3 | Lecture 3 | ⎕ | |||

| 2.4 | Lecture 4 | ⎕ | |||

| 2.5 | Lecture 5 | ⎕ | |||

| 3 | Peer Journal Club | Topic/Presenter/Date | |||

| 3.1 | Internal Medicine | ⎕ | |||

| 3.2 | Neuro | ⎕ | |||

| 3.3 | OB/GYN | ⎕ | |||

| 3.4 | Peds | ⎕ | |||

| 3.5 | Radiology | ⎕ | |||

| 3.6 | Dermatology | ⎕ | |||

| 3.7 | Anesthesia | ⎕ | |||

| 3.8 | Surgery | ⎕ | |||

| 4 | Web Based Training Modules | Date Viewed | |||

| 4.1 | GH Practitioner’s Guide 1 | ⎕ | |||

| 4.2 | GH Practitioner’s Guide 2 | ⎕ | |||

| 4.3 | GH Practitioner’s Guide 3 | ⎕ | |||

| 4.4 | Photography and Ethics | ⎕ | |||

| 5 | Simulation Lab Skills Training | Date Attended | |||

| 5.1 | Ethics Simulation | ⎕ | |||

| 5.2 | OB/GYN and Pediatrics Simulation | ⎕ | |||

| 5.3 | Surgery/Anesthesiology Simulation | ⎕ | |||

| 6 | Global Rotation | Date/Location/Supervisor Name—Email (as applicable) | |||

| 6.1 | Global Rotation | ⎕ | |||

| 6.2 | Post-Trip Debriefing | ⎕ | |||

| 7 | Scholarly Project | Description/Presentation or Publication Date | |||

| 7.1 | Scholarly Project | ⎕ | |||

| 7.2 | Global Healt Day Poster | ⎕ | |||

Appendix 4

McGaw Global Health Clinical Scholars mentor responsibilities

The objective of McGaw GHCS is to provide trainees (residents and fellows) with training in clinical care in resource limited settings worldwide. Since trainees from many different departments/divisions will participate in this program, it is crucial to have faculty mentors involved who represent each specialty in order to support, supervise, and mentor our residents and fellows. Each mentor should use their specialized knowledge in teaching the mentees. The mentor should strive to develop meaningful relationships with the mentees. Should the mentor come across any concerns or questions please contact the program director.

Mentors support their mentees by:

Monitoring trainee progress to graduation using the Box Checklist

Supporting development of their final scholarly project

-

Meeting regularly (1/time a month) and monitor to accomplish scholarly project

○ Frequency is determined in Mentee/Mentor agreement (e.g. once every 2 months check in project and once a month leading up to the site rotation)

Developing action strategies to support the mentee’s learning

Providing mentorship and support during the mentee’s Global Field Experience (GFE)

Providing site and specialty-specific pre-departure preparation*

The mandatory requirements for each mentor within their specialty are:

-

Development of specialty-specific competencies and accompanying lecture series

Please send us the lecture schedule as soon as possible

Provision of simulation instruction for your particular field

Participation in development and delivery of GHCS didactic curriculum

Additionally, the GHCS Mentor is asked to adhere and assist with scheduling and deadlines as they arise.

*The pre-departure support and preparation should be site specific, for example an orientation specific to Hillside Healthcare Clinic in Belize as the program provides general pre-departure orientation. Mentors are encouraged to include past participants for peer orientation about the sites.

Appendix 5

Ethics and skills simulation series

Background

While the benefits of global health rotations for trainees from high income countries have been well-documented, many ethical issues have arisen around skills and behaviors toward local expectations and norms, inappropriate patient care, professionalism, and interpersonal communication.33 Furthermore, given a high degree of specialization during training in tertiary care centers in the United States, trainees have a much narrower scope of clinical practice than in many other settings with different resources and care delivery needs. When trainees participate in clinical rotations in low-resource settings, they often report feeling pressure to perform beyond their current scope of practice or difficulties managing care with fewer resources.16,34 To address these ethical issues, high quality pre-departure teaching around ethics should be taught by instructors from sending institutions and should be the standard of practice for global health rotations.35 Numerous approaches to pre-departure training have been implemented and are utilized in our curriculum including online modules, clinical case-based simulation sessions and didactic lectures. More recently, simulation curricula have been added including Ethics Simulation in Global Health Training (ESIGHT) with the goal of teaching ethical decision making in the midst of common dilemmas encountered during STEGH.36

In this program, we implemented and adapted the ESIGHT curriculum to address ethical challenges faced in global health work, including navigating or practicing outside one’s clinical scope or personal comfort. A skills curriculum was also implemented in 2015 to review core surgery, anesthesia, obstetrics and gynecology and pediatric clinical skills that may be encountered, allowing each trainee to assess their own proficiency in each skill. The goals of the skills and simulation series are 3: (1) to provide trainee physicians with clinical skills and strategies to provide safe and high-quality medical care in resource limited settings, (2) to assess and augment a universal set of clinical skills as well as emergent or life-saving skills that may be relevant to trainees from across varied specialties engaged in global health work, and (3) to provide trainees with skills to navigate ethical challenges and maintain ideals of professionalism regarding the possibility of performing outside their typical clinical scope of practice. The simulation series is grounded in ethical clinical practice with one dedicated Global Health Ethics simulation and 2 skills-based simulations: OBGYN/Pediatrics skills and Surgery/Anesthesia skills.

Each simulation is made up of the following general components: pre- and post-testing, participation in the simulation or skills station, and post-scenario debriefing.

Global health ethics simulation

General structure

This ethics simulation curriculum was developed from numerous existing resources and input from global health faculty of various specialties. The curriculum was purchased and adapted from ESIGHT creators who hosted an in-person training for faculty and standardized patients.36 Our own McGaw ESIGHT curriculum modified the faculty debriefing, adding further detail, framework and structure to the debriefing guide specifically around decision making for our trainees, background on ethical concepts, and structured guidance for facilitators. Each year, we have continued to develop our debriefing guides based on the needs of our trainees and feedback from the previous simulations. The McGaw ethics simulation curriculum re-creates 3 ethically challenging scenarios that trainees are likely to be exposed to while working in a resource limited setting. Each scenario is very specific and the principle challenges addressed are: privacy and confidentiality, informed consent, and scope of practice. Each trainee receives background information then enters the 10 to 15 minute case and must navigate the challenging scenario and make decisions based on feedback from a specially trained Standardized Patient (SP). Additional trainees observe the scenario out of view of the main participant. Global health faculty then facilitate a structured debriefing of the situation, actions and feelings witnessed and experienced by all trainees. The ethics simulation is offered annually.

Simulation staffing: We attempt to create an atmosphere which reflects traditional dress, culture, and language. Actors who have experience in simulation are hired to portray these settings. They are trained to provide the regional context of each specific case and are trained to create ethical tensions and to challenge trainees to take an action. Along with the SP director of the sim lab, the SPs are also debriefed prior to and after the actual simulation. Global health faculty are trained in debriefing prior to the simulation and are provided with a structured debriefing script to be used during the event.

Pre and post simulation evaluation: A confidential survey is distributed to each trainee who participates in the simulation. The pre-simulation survey addresses whether the trainee has been exposed to each ethical issue and has a strategy for dealing with the ethical issue. The post-simulation survey, in addition to these questions, asks if these scenarios highlight dilemmas that could be faced in resource limited settings.

Simulation scenarios: Each simulation case is presented in a simulation lab with visuals, sounds, and props to create a high-fidelity version of patient scenarios in a woman’s home in rural Malawi, a community in Sierra Leone, and a Haitian Hospital.

Case #1: An SP plays the role of a pregnant woman in Malawi addressing HIV treatment when her husband does not know her HIV status.36 This case is specifically developed to address the ethical principles of privacy and confidentiality.

Case #2: A young woman currently in extremis from obstructed labor in Sierra Leone.36 The participant must work with a community health worker and the patient’s mother in law, both played by SPs, to navigate a challenging social situation. This case is specifically designed to address the ethical principle of informed consent.

Case #3: An SP is acting as a resident in a Haitian Hospital who asks the participant to take care of the ward for a few days while the resident returns home for a family emergency. There are no other doctors at the hospital except for an obstetrician who is currently in the operating room. This case addresses the principle of scope of practice.

Debriefing: After each case, a global health faculty member leads a 15 minute debriefing session in which the trainees jointly reflect on the experience that they shared during the simulation. The focus of the debriefing is 2-fold: (1) Critical reflection: to consciously reflect on the impact various ethical issues had on the trainees’ emotional state and moral values and (2) strategy: to jointly work out what an appropriate response would be if the trainees found themselves in a similar situation. Each global health faculty member is given a general debriefing guide along with a structured debriefing guide with specific questions and ethical principles and norms to discuss in each case.

Skills-based simulations

General structure: Each Skill-Simulation day follows the same overall structure:

Pre-simulation trainee survey given about skills and procedures being taught

Presentation of patient case or skill that would be encountered in a global health setting

Individual/group participation or role playing of the case or skill

Debriefing of the case and skills reviewed with global health faculty while specifically focusing on reflection of ethical frameworks and an exploration of decision making

Each station consists of the following structure:

Review of a case where the skill is used in a resource limited setting

Demonstration and discussion of performing that skill by trainee or global health faculty member with expertise in that skill

Debriefing of trainee’s comfort level, scope of practice (SOP), familiarity and performance of that skill

If the skill is within the trainee’s SOP**, they are able to practice that skill further with support and guidance from a faculty member

**For example- simple fracture management may fall within the SOP of certain family medicine, emergency medicine, surgical subspecialists, and pediatric trainees but is not within the SOP for neurology, most internal medicine, urology, dermatology, obstetrics/gynecology, anesthesia, among others

Surgery anesthesia simulation skills

Peripheral IV insertion and basics of fluid resuscitation

Administering Moderate Sedation

Bag/Mask Ventilation

Suturing

Incision and Drainage

Simple Fracture Management

Trauma First Responder’s Skills*

OBGYN/pediatrics simulation skills

Postpartum Hemorrhage/Estimating Blood Loss

Obstetric Suturing

Obstetric Ultrasound

Basic Gynecology and Evaluation of the Lower Female Genital Tract

Vaginal Delivery

Helping Babies Breathe curriculum*

The Surgery/Anesthesia and OBGYN/Pediatrics skill simulations are framed in case-based scenarios and the aim is to teach and assess scope of comfort performing each skill. Skills were determined by global health mentors and faculty from the departments of obstetrics and gynecology, surgery, anesthesia, and pediatrics. The initial skills taught for the OBGYN simulation were based on previously used skill curriculum for fourth year medical students. The primary objective of these simulations is to not only to teach appropriate basic skills but to equip trainees with an ethical framework for making decisions about performing these skills. We emphasize identifying SOP, continued self-assessment and personal comfort with these procedures to guide decision-making. These simulations are offered annually.

Simulation staffing: Each station is co-lead by a trainee or faculty member who is experienced in the particular skill and a global health faculty member who leads the debriefing. The skilled faculty member is taught the scenario and context of the skill prior to the simulation. At each station, the skilled faculty member demonstrates the skill and trainees are given the opportunity to both practice the skill and reflect on their personal competency of that skill. The global health faculty member then leads a discussion about the scenario itself, the trainees’ personal proficiency of the skill and reflection on if and when to perform the skill.

Pre and post simulation evaluation: Before and after the simulation, trainees are asked about their perception of the benefit versus harm of each individual skill performed, both within and outside their scope of practice in both routine or emergent circumstances.

*First responder and universal skill training: Valuable first-responder or lay-person basic life support skills were also incorporated into the curriculum. A session of the Trauma First Responder’s course was provided for all surgery/anesthesia skills simulation participants. This is a lay person’s course for responding to violence and injuries.37 Additionally, Helping Babies Breathe was provided for all OBGYN/Peds skills simulation participants which teaches basic neonatal resuscitation.38 Finally, the future iteration of the skills components will be based in scenarios and include only first responder or lay-person life support skills such as those taught in BLSO, HBB, ACLS, and STOP the bleed.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding:The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: Conception and Design: JM, SG, ADP

Collection and Assembly of Data: JM, CF, ADP

Data Analysis and Interpretation: JM, CF, ADP

Manuscript Writing: All Authors

ORCID iD: Ashti Doobay-Persaud  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7063-4429

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7063-4429

References

- 1. 2010 Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire. AAMC. http://www.aamc.org/data/gq. Published July 2019. Accessed June 15, 2018.

- 2. Drain PK, Primack A, Hunt DD, Fawzi WW, Holmes KK, Gardner P. Global health in medical education: a call for more training and opportunities. Acad Med. 2007;82:226-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, et al. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84:320-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tupesis JP, Jacquet GA, Hilbert S, et al. The role of graduate medical education in global health: proceedings from the 2013 Academic Emergency Medicine consensus conference. Acad Emerg Med 2013;20:1216-1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bazemore AW, Henein M, Goldenhar LM, Szaflarski M, Lindsell CJ, Diller P. The effect of offering international health training opportunities on family medicine residency recruiting. Fam Med. 2007;39:255-260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kerry VB, Walensky RP, Tsai AC, et al. US medical specialty global health training and the global burden of disease. J Glob Health. 2013;3:020406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. St. Clair, Pitt MB, Bakeera-Kitaka S, et al. Global health: preparation for working in resource-limited settings. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20163783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coombs PG, Feldman BH, Lauer AK, Paul Chan RV, Sun G. Global health training in ophthalmology residency programs. J Surg Educ. 2015;72:e52-e59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ho T, Bentz M, Brzezienski M, et al. The present status of global mission trips in plastic surgery residency programs. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:1088-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Powell AC, Mueller C, Kingham P, Berman R, Pachter HL, Hopkins MA. International experience electives, and volunteerism in surgical training: a survey of resident interest. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:162-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McCunn M, Speck RM, Chung I, Atkins JH, Raiten JM, Fleisher LA. Global heath outreach during anesthesiology residency in the United States: a survey of interest, barriers to participation, and proposed solutions. J Clin Anesth. 2012;24:38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lungren MP, Horvath JJ, Welling RD, et al. Global health training in radiology residency programs. Acad Radiol. 2010;18:782-791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta AR, Wells CK, Horwitz RI, Bia FJ, Barry M. The international health program: the 15-year experience with Yale University’s internal medicine residency program. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61:1019-1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bissonette R, Routé C. The educational effect of clinical rotations in nonindustrialized countries. Fam Med. 1994;26:226-231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elansary M, Graber LK, Provenzano AM, Barry M, Khoshnood K, Rastegar A. Ethical dilemmas in global clinical electives. J Glob Health (Columbia Univ). 2011;1:24-27. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Logar T, Le P, Harrison JD, Glass M. Teaching corner: “first do no harm”: teaching global health ethics to medical trainees through experiential learning. J Bioeth Inq. 2015;12:69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Doobay-Persaud A, Evert J, DeCamp M, et al. Practising beyond one’s scope while working abroad. Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e1009-e1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jesus JE. Ethical challenges and considerations of short-term international medical initiatives: an excursion to Ghana as a case study. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:17-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crump JA, Sugarman J; Working Group on Ethics Guidelines for Global Health Training (WEIGHT). Ethics and best practice guidelines for training experiences in global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;86:1178-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sweet LR, Palazzi DL. Application of Kern’s six-step approach to curriculum development by global health residents. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2015;28:138-141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Evert J, Stewart C, Chan K, et al. Developing Residency Training in Global Health: A Guidebook. San Francisco, CA: Global Health Education Consortium; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Arya AN, Evert J. Global Health Experiential Education: From Theory to Practice. New York: Routledge; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Loh LC, Cherniak W, Dreifuss BA, Dacso MM, Lin HC, Evert J. Short term global health experiences and local partnership models: a framework. Global Health. 2015;11:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Elansary M, Phil M, Thomas J, Graber J, Rabin T. AMSA global health clinical ethics pre-departure workshop student resource guide. http://www.amsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/AMSA-Clinical-Ethics-Pre-Departure-Workshop-Student-Resource-Guide-FINAL.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- 25. The practitioner’s guide to global health. EdX and Boston University. https://www.edx.org/course/the-practitioners-guide-to-global-health. Published 2019. Accessed June 2, 2018.

- 26. Ethics and photography in developing countries. Unite for Sight. http://www.uniteforsight.org/global-health-university/photography-ethics. Published 2015. Accessed June 2, 2018.

- 27. Preparing for international health experiences: a practical guide. Child Family Health International. https://www.cfhi.org/preparing-for-international-health-experiences-a-practical-guide. Published 2019. Accessed June 1, 2018.

- 28. Aperian Global. Quick guide to strengthen your inclusive behaviors. https://www.aperianglobal.com/site-resources/quick-guides/. Published 2019. Accessed June 10, 2018.

- 29. Jayaraman SP, Ayzengart AL, Goetz LH, Ozgediz D, Farmer DL. Global health in general surgery residency: a national survey. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:426-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. St. Clair NE, Butteris S, Cobb C, et al. S-PACK a modular and modifiable, comprehensive pre-departure preparation curriculum for global health experiences. Acad Med. 2019;94:1916-1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McGaw clinical scholars programs. McGaw Medical Center of Northwestern University. https://www.mcgaw.northwestern.edu/benefits-resources/educational-resources/mcgaw-clinical-scholar-programs.html. Published 2019. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- 32. McHenry MS, Baenziger JT, Zbar LG, et al. Leveraging economies of scale via Collaborative Interdisciplinary Global Health Tracks (CIGHTs). Acad Med. 2020;95:37-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gladding S, Zink T, Howard C, Campagna A, Slusher T, John C. International electives at the University of Minnesota global pediatric residency program: opportunities for education in all Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education competencies. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12:245-250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Harrison J, Logar T, Le P, Glass M. What are the ethical issues facing global health trainees working overseas? A multi-professional qualitative study. Healthcare. 2016;4:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Purkey E, Hollaar G. Developing consensus for postgraduate global health electives: definitions, pre-departure training and post-return debriefing. BMC Med Educ. 2016;16:159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Asao S, Lewis B, Harrison JD, et al. Ethics Simulation in Global Health Training (ESIGHT). MedEdPORTAL. 2017;13:10590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Trauma responders unify to empower communities. Northwestern Trauma and Surgical Initiative. https://www.ntsinitiative.org/chicago-trauma-first-responders-cou. Updated 2019. Published 2018. Accessed June 20, 2019.

- 38. Niermyer S, Keenan WJ, Little GA, et al. Helping Babies Breath, Learner Workbook. Elk Grove, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2010. [Google Scholar]