Abstract

Introduction:

Unilateral neglect is a debilitating condition that can occur after stroke and can affect a variety of domains and modalities, including proprioception. Proprioception is a sensorimotor process essential to motor function and is thus important to consider in unilateral neglect. To date, there has not been a comprehensive review of studies examining the various aspects of proprioceptive impairment in unilateral neglect after stroke. This review aimed to determine if people with unilateral neglect have more severe proprioceptive impairments than those without unilateral neglect after stroke.

Methods:

The MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, CINAHL and Web of Science databases were searched from inception to September 2019 using an a priori search strategy. Two independent reviewers screened abstracts and full texts, and extracted data from the included full texts. A third reviewer resolved disagreements at each step. Risk of bias was assessed using the AXIS Quality Assessment tool.

Results:

A total of 191 abstracts were identified, with 56 eligible for full-text screening. A total of 18 studies were included in the review and provided evidence that people with unilateral neglect have more severe proprioceptive impairment than people without unilateral neglect. This impairment is present in multiple subtypes of unilateral neglect and aspects of proprioception. Most studies had a moderate risk of bias.

Conclusion:

People with unilateral neglect after stroke are more likely to have impaired processing of multiple types of proprioceptive information than those without unilateral neglect. However, the available evidence is limited by the large heterogeneity of assessment tools used to identify unilateral neglect and proprioception. Unilateral neglect and proprioception were rarely assessed comprehensively.

PROSPERO Registration: CRD42018086070.

Keywords: Rehabilitation, sensorimotor, neurology, unilateral neglect, proprioception, stroke, systematic review

Introduction

Unilateral neglect (UN) is an umbrella term for a range of clinical presentations, characterised by the failure to report, respond, or orient to novel or meaningful stimuli presented on the side opposite to the brain lesion.1 Depending on the method used for assessment, UN is estimated to affect 23.5%–67.8%2,3 of people after stroke. However, the most commonly used assessments (cancellation tasks and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) Item 11) indicate the incidence is ~30%.4,5 UN is linked to greater length of hospital stay, higher incidence of falls, and a reduced likelihood of home as a discharge destination.2,6–9 These negative sequelae are largely due to the poor functional outcomes that are associated with UN, which persist at 1-year post-stroke in 30%–60% of patients.10–12 Despite the high incidence and negative functional consequences of UN, there is no consensus about effective yet clinically feasible assessment and treatment strategies for the condition.13–17

The lack of appropriate assessments and effective treatment strategies is an indication of the complexity of UN. UN is often associated with larger lesion volumes3 and is not the result of lesions in a single location. Rather, it is the result of impaired functional connectivity between brain regions associated with attention, sensorimotor and visual processing, notably the frontoparietal networks.18–20 As a result, symptoms of UN are varied and can present in a range of domains (visuospatial, auditory and sensorimotor) and spaces (personal, peri-personal and extra-personal).21,22

Clinical assessment of UN should target a combination of these domains and spaces, and yet, many current standardised clinical assessments are limited to only one.13 The most common form of UN assessment uses pen-and-paper tasks, including line bisection, shape cancellation, or figure copying.14 These tasks are unable to capture visuospatial neglect in the peri-personal and extra-personal spaces and do not account for auditory or sensorimotor domains.13 Given this limited assessment scope, it is not surprising that UN is often considered a singular condition and associated solely with visuospatial impairment, neglecting other domains, and thus, the heterogeneous nature of the condition.9,23

Importantly, a sensorimotor impairment in UN that is often clinically neglected is proprioception.24 Proprioception, as defined by Sherrington in 1906, derives from the Latin word proprius, meaning ‘one’s own’, combined with the concept of perception and thus refers to ‘perceiving one’s own self’.25 Proprioception is largely considered as the processes enabling joint movement, position detection and muscle force judgement (for review, see Hillier et al.25). However, information about the size and shape of body parts is crucial for proprioception.26 Explicitly, to sense the position and movement of ‘one’s own self’ is impossible without the information about what that ‘self’ is. Therefore, an updated and emerging definition of proprioception includes the body representation, defined as the stored internal model of the body and its parts.26–28 Distinct methods of assessing body representation include judgement of laterality, body axes and body topography.29,30

Standardised clinical assessments of proprioception typically involve the detection or judgement of passively imposed joint movements in the absence of vision.31,32 These capture a patient’s ability to detect when and where a body part is moving, without accounting for body representation.33 Skilled movement emerges from the judgement of movement direction, magnitude and the nature of the moving parts, provided by the body representation. Given that stroke rehabilitation focuses largely on the restoration of skilled movement, it is important to consider impairments in all aspects of proprioception. In the context of the complex presentation of UN, it is conceivable that multiple aspects of proprioception are impaired. However, this is unknown because, to date, no review examining proprioception in UN has been conducted.

Impaired proprioception is associated with poor motor and functional outcomes at all stages of stroke.34,35 Thus, it should be an essential target in stroke rehabilitation, particularly in patients with UN. Therefore, the primary aim of this systematic review is to determine whether proprioception, including the body representation as part of the definition, is more impaired in people with UN compared to those without after a stroke. The secondary aims are to identify the assessments used to detect UN and its domains (e.g. spatial, extra-personal).

Methods

Protocol and registration

The protocol for this systematic review is registered in PROSPERO, under the registration number CRD42018086070 and can be accessed at the following link: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=86070.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) cross-sectional design or intervention studies that provided cross-sectional data at baseline, (2) participants were adults aged 18 years and over, (3) participants had first-time stroke confirmed on medical imaging, (4) employed at least one standardised assessment of UN, and (4) at least one assessment of proprioception and (5) had data reported for participants with UN (UN+) and without (UN−). There was no restriction on publication year or language. Studies were excluded if they used clinical tests that assessed only balance and/or vestibular function and/or sensorimotor function that was not specific to proprioception.

Search strategy and study selection

This review followed Cochrane Methodology and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) reporting guidelines.36 The CINAHL, Embase, MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science electronic databases were searched from inception to 10 September 2019 using a pre-established search strategy developed by all members of the study team and reviewed by a university librarian (Supplemental Appendix 1). Two review authors (G.F. and D.K.) screened abstracts and full texts independently, and a third review author (C.Q.d.O.) resolved disagreements at each step of study selection. Screening was conducted using the Covidence software. Studies in languages other than English were translated using an online translation service.

Data extraction

Two review authors (G.F. and C.Q.d.O.) independently extracted data using a standardised excel spreadsheet based on the Cochrane Data Extraction Template.37 Extracted information included studies’ authors, year, aims, setting, population, procedures; participant’s recruitment, demographics and baseline characteristics, and completion rates; type of outcome measures used to assess UN and proprioception, assessment data for UN and proprioception with time points of collection; and the suggested mechanisms of interaction between proprioception and neglect. Determination of UN was based on standardised and validated clinical or laboratory tests developed to assess UN, such as Albert’s Test,38 Rivermead Behavioural Inattention Test (BIT)39 and Catherine Bergego Scale (CBS)40 (for summary, see Menon and Korner-Bitensky13). Assessment of proprioception included standardised tests in any of the following categories: (1) movement detection/direction discrimination, for example, the distal proprioception test;41 (2) joint position judgement or reproduction for example, the Wrist Position Sense Test;42 (3) force judgement or matching, for example, finger force reproduction as per Walsh et al.;43 and (4) tests of body representation, for example, the RecogniseTM App for hand laterality.44 Assessments of proprioception that had not been formally validated were eligible for inclusion, given the lack of research into tests of certain aspects of proprioception. Where information was not available in the published study, details were requested from the corresponding author.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias was evaluated by two review authors (G.F. and C.Q.d.O.), independently using the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS), a 20-item scale developed using a Delphi panel consensus assessing 5 domains – Introduction (1 item), Methods (10 items), Discussion (5 items), Conclusion (2 items), and Other (2 items).45 The AXIS requires a Yes/No/Unsure assessment for each item, for example, ‘Was the sample size justified?’ and ‘Were the results for the analyses described in the methods presented?’ The full list of AXIS items is reported in Supplemental Appendix 4. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and when necessary, with a third review author (D.K.). Prior to discussion, percent agreement between the two reviewers on AXIS items was 90.28%. The AXIS acknowledges the issues with the summation of checklists for study quality,46,47 and as such, does not have published cut-off scores to categorise studies as low, medium, or high risk of bias.45 Therefore, the authors used a quartiles system for categorising risk of bias according to the number of AXIS items met (low risk >15, moderate risk 10–15, high risk 4–9 and very high risk <4).48

Summary measures and data synthesis

A descriptive synthesis of (1) between-group differences of UN+ and UN− stroke patients, and (2) types of assessments of UN and proprioception used in the included studies was conducted. The summary of study results was presented in separate tables for continuous (mean values and standard deviations, medians and interquartile range (IQR)) and dichotomous data (percentages and total number of participants). Effect size was calculated using Hedges g for continuous outcomes due to small and uneven group sizes49 and odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes.50 Risk of bias assessment was descriptively synthesised and presented in tabular format.

Results

Study selection

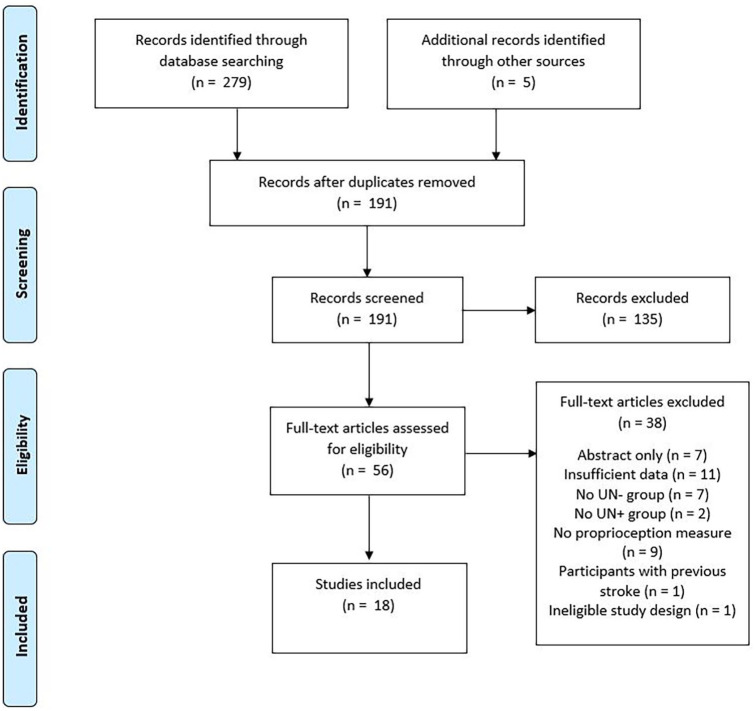

A total of 284 titles and abstracts were identified, with 191 eligible for abstract screening after duplicate removal, and 56 eligible for full-text screening. A total of 18 studies were included in the review23,51–67 (see Figure 1). The predominant reasons for exclusion at full-text review were inadequate data reporting and a lack of a measure of proprioception. The full list of excluded studies and the reasons for their exclusion can be found in Supplemental Appendix 2.

Figure 1.

Flow of studies through review.

Study characteristics

Population

The complete characteristics of the participants included in the studies are summarised in Table 1. A combined total of 959 participants were included in the studies, 246 in the UN+ group and 713 in the UN− group. All studies had a small sample size (mean = 50, SD = ±68, range = 6–281). The mean age and standard deviation were 60.3 ± 5.4 years (UN+ = 60.9 ± 5.6, UN− = 59.8 ± 5.4), and the majority of participants were male (65%). Most studies recruited participants in the sub-acute phase (3 weeks to 6 months post-stroke); however, two studies59,63 collected data from participants in the chronic phase (more than 6 months after stroke). Five studies23,53,64–66 recruited stroke populations in different phases (chronic, acute, sub-acute), and one study67 limited recruitment to the acute phase (less than 3 weeks post-stroke).

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies, by proprioceptive test type.

| Author | Setting | Time since stroke | Sample size | Age (mean, SD) | Lesion side | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN+ | UN− | UN+ | UN− | UN+ | UN− | |||

| Movement detection/judgement | ||||||||

| Meyer et al.62 | Inpatient rehab | Sub-acute | 27 | 95 | 68 (60.2–77.7)a | 66.7 (58.7–75.7)a | NR | NR |

| Schmidt et al.63 | NR | Chronic | 7 | 15 | 61.7 (14.8) | 66.3 (12.2) | R = 7 | R = 15 |

| van Stralen et al.67 | ASU | Acute | 9 | 47 | 58.9 (12.4) | 61.5 (16.1) | R = 8, 1 = NR | R = 14, L = 33 |

| Joint position matching | ||||||||

| Borde et al.61 | NR | NR | 6 | 3 | 63.3 (9.4) | 62.33 (5.77) | R = 6 | R = 3 |

| Borde et al.60 | Inpatient rehab | Sub-acute | 10 | 20 | 63.4 (8.8) | 62.5 (11.9) + 61.2 (15.5)b | R = 10 | R = 10, L = 10 |

| Semrau et al.65 | ASU, Inpatient rehab | Acute, sub-acute | 35 | 123 | 59 (20–86) | 63 (18–89) | R = 31, L = 4 | R = 67, L = 55, B = 1 |

| Semrau et al.64 | ASU, Inpatient rehab | Acute, sub-acute | 59 | 222 | 62.32 (15.19) | 60.64 (14.46) | NR | NR |

| Laterality | ||||||||

| Baas et al.51 | NR | NR | 7 | 15 | 51.47 (13.62) | 61.29 (7.89) | R = 7 | R = 15 |

| Coslett54 | NR | Sub-acute, chronic | 3 | 3 | 63.67 (10.41) | 58.67 (11.37) | NR | NR |

| van Stralen et al.67 | ASU | Acute | 9 | 47 | 58.9 (12.4) | 61.5 (16.1) | R = 8, 1 = NR | R = 14, L = 33 |

| Vromen et al.59 | Inpatient rehab | Chronic | 8 | 12 | 55.3 (8.4) | 59.5 (6.9) | R = 8 | R = 12 |

| Body axis/midline | ||||||||

| Barra et al.52 | NR | Sub-acute | 10 | 8 | 63.6 (7.53) | 53.12 (18.26) | R = 7, L = 3 | R = 3, L = 5 |

| Heilman et al.55 | NR | NR | 5 | 5 | 48 (10.3) | 58.6 (6.27) | R = 5 | L = 5 |

| Richard et al.56 | Inpatient rehab | Sub-acute, chronic | 8 | 8 | 61.13 (12.45) | 52.13 (13.61) | R = 8 | R = 8 |

| Saj et al.58 | Inpatient rehab | NR | 6 | 6 | 58 (12.7) | 59.2 (11.2) | R = 6 | R = 6 |

| Tosi et al.66 | Inpatient rehab | Acute, chronic | 7 | 38 | 68.42 (7.23) | 65.97 (12.5) | R = 7 | R = 16, L = 21, B = 1 |

| Body topography | ||||||||

| Cocchini et al.53 | Inpatient rehab | Sub-acute | 14 | 24 | 67.21 (8.43) | 58.00 (10.7) + 59.45 (15.9)b | R = 14 | R = 13, L = 11 |

| Di Vita et al.23 | NR | Sub-acute, chronic | 7 | 16 | 65.29 (10.29) | 64.44 (13) | R = 6, L = 1 | R = 12, L = 4 |

| Rousseaux et al.57 | NR | NR | 9 | 6 | 53.1 (13.2) | 46.3 (9.3) | R = 9 | R = 6 |

SD: standard deviation; UN: unilateral neglect; UN+: participants with UN; UN−: participants without UN; NR: not reported; ASU: acute stroke unit; R: right; L: left; B: bilateral.

Median and IQR presented.

Two UN− groups, first listed (R) side lesion, second (L) sided lesion. Acute defined as <3 weeks post-stroke, sub-acute 3 weeks to 6 months post-stroke, and chronic >6 months post-stroke.

Proprioception assessment

Proprioception was assessed by 13 different methods across the studies, as described in Table 2. Three studies62,63,67 assessed solely the detection or discrimination of movement. Five studies60–62,64,65 assessed proprioception via a limb-matching task. Of the four studies51,54,59,67 that examined laterality, three51,54,59 used a hand laterality task and one67 utilised a laterality task in which participants were required to point to the left or right hand of human stick figure drawings in various orientations. Five studies52,55,56,58,66 used an assessment that required participants to identify the location of the body midline or a body axis. Finally, three studies23,53,57 examined perceptions of body topography by asking participants to arrange tiles printed with body parts, detect targets placed on their body and localise points stimulated on their trunk, respectively. A single study67 reported two distinct proprioception outcomes, laterality and movement detection. No study investigated force matching.

Table 2.

Assessment descriptions.

| Author | UN test(s) | Type of UN assessment | Proprioception test(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Movement detection | |||

| Meyer et al.62 | SCT | Pen and paper | Em-NSA, TFT (0–3) |

| Schmidt et al.63 | LeCT, SCT, LBT, Figure Copying, Reading Test | Pen and paper | Arm Position Test–Error |

| van Stralen et al.67 | SCT | Pen and paper | RASP |

| Joint position matching | |||

| Borde et al.61 | LCT, Observation, Environment Description, Double Letter Cancellation | Pen and paper, Extra-personal | Upper limb position reproduction, TFT |

| Borde et al.60 | LBT, LeCT | Pen and paper | Upper limb position reproduction |

| Semrau et al.65 | BIT | Behavioural | Robotic Arm Position Matching Task, TFT |

| Semrau et al.64 | BIT | Behavioural | Robotic Arm Position Matching Task |

| Laterality | |||

| Baas et al.51 | Fluff test (primary), LBT, BCT | Personal | Hand Laterality |

| Coslett54 | LBT, SCT, LCT | Pen and paper | Hand Laterality |

| van Stralen et al.67 | SCT | Pen and paper | Bergen Laterality Test |

| Vromen et al.59 | SCT, subjective neglect questionnaire | Pen and paper, self-report | Hand Laterality |

| Body axis/midline | |||

| Barra et al.52 | BCT, CBS, LBT | Pen and paper, functional | Longitudinal Body Axis |

| Heilman et al.55 | LBT | Pen and paper | Pointing to body midline |

| Richard et al.56 | BCT, Scene Copy, LBT (2/3) | Pen and paper | Pointing to body midline |

| Saj et al.58 | BCT, LBT, Scene Copy | Pen and paper | Longitudinal Body Axis |

| Tosi et al.66 | Biasch’s Test | Personal | Arm bisection task |

| Body topography | |||

| Cocchini et al.53 | SCT, LCT | Pen and paper | Body Exploration Fluff Test |

| Di Vita et al.23 | LeCT, LCT, Use of Common Objects Test, Sentence Reading, Wundt–Jastrow Area Illusion | Personal | Body Topography |

| Rousseaux et al.57 | LBT, BCT, CBS | Pen and paper, functional | Tactile Stimulation Localisation |

UN: unilateral neglect; SCT: star cancellation test; Em-NSA: Erasmus Modifications to the Nottingham Sensory Assessment; TFT: thumb finding test; RASP: Rivermead Assessment of Somatosensory Perception; LCT: line cancellation; LeCT: letter cancellation; LBT: line bisection test; BIT: behavioural inattention test; BCT: bell cancellation; CBS: Catherine Bergego Scale.

Risk of bias

According to the AXIS risk of bias assessment, 2 studies were rated as low risk of bias,52,66 12 as moderate risk of bias23,51,54,56,58–65,67 and 3 as high risk of bias53,55,57 (see Table 3, with full AXIS items and result reported in Supplemental Appendices 3 and 4). The two studies using the CBS as a measure of UN had an AXIS rating of low52 and high risk of bias.57 The main sources of risk of bias were sampling strategy, and consistency in reporting participant characteristics and results for all planned analyses. All studies defined their target population, reported internally consistent results, and justified their discussion and conclusions. Only one study52 justified their sample size and reported non-response to recruitment. Twelve studies23,51,53–58,60,61,65,66 failed to report their methodological limitations and four studies53,57,60,61 did not employ a validated assessment tool for UN. Five studies23,53–56 did not present results for all planned analyses and six55,57–59,63,67 did not provide sufficient participant demographic data. Finally, seven studies51,53,55,57,58,63,65,67 used convenience samples.

Table 3.

AXIS risk of bias assessment summary – percentages of items satisfied.

| Author | Intro | Methods | Results | Conclusions | Other | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baas et al.51 | 100% | 60% | 75% | 50% | 50% | Moderate |

| Barra et al.52 | 100% | 90% | 80% | 100% | 100% | Low |

| Borde et al.61 | 100% | 80% | 90% | 50% | 0% | Moderate |

| Borde et al.60 | 100% | 70% | 100% | 50% | 100% | Moderate |

| Cocchini et al.53 | 0% | 20% | 50% | 50% | 0% | High |

| Coslett54 | 100% | 70% | 75% | 50% | 0% | Moderate |

| Di Vita et al.23 | 100% | 70% | 75% | 50% | 100% | Moderate |

| Heilman et al.55 | 100% | 40% | 25% | 50% | 50% | High |

| Meyer et al.62 | 100% | 80% | 75% | 100% | 100% | Moderate |

| Richard et al.56 | 100% | 80% | 50% | 50% | 50% | Moderate |

| Rousseaux et al.57 | 100% | 60% | 50% | 50% | 50% | High |

| Saj et al.58 | 100% | 60% | 50% | 50% | 100% | Moderate |

| Schmidt et al.63 | 100% | 50% | 50% | 100% | 100% | Moderate |

| Semrau et al.65 | 100% | 70% | 75% | 50% | 50% | Moderate |

| Semrau et al.64 | 100% | 70% | 75% | 100% | 50% | Moderate |

| Tosi et al.66 | 100% | 90% | 80% | 50% | 100% | Low |

| van Stralen et al.67 | 100% | 70% | 75% | 100 | 100% | Moderate |

| Vromen et al.59 | 100% | 80% | 75% | 100% | 100% | Moderate |

Synthesis of results

Proprioceptive impairment in UN

The majority of studies in this review support the existence of more severe proprioceptive impairment in UN+ compared to UN−. The two studies with low risk of bias reported conflicting results on the relationship between proprioceptive impairment and UN. One study52 reported a body axis judgement error correlation of r = −0.61 and r = −0.56 for the CBS and Line Bisection Test, respectively, indicating that individuals with UN had more severe proprioceptive impairment. Another study66 reported a mean difference of 2.4 cm in forearm bisection measurement between people with and without UN, with a small effect size indicating greater proprioceptive impairment in UN+ group (Hedges g = 0.22). Of the 13 studies with a moderate risk of bias, 77% (n = 10) reported medium or large effect sizes indicating more severe proprioceptive impairment in people with UN.

The studies with the largest sample size64,65 reported large and moderate effect sizes (Hedges g = 1.59 and 1.43, and 0.63, respectively) indicating greater proprioceptive impairment in people with UN than those without. All three studies with a high risk of bias53,55,57 reported significantly more severe proprioceptive impairment in UN+. A descriptive synthesis of the findings of the included studies’ results is presented in Table 4 (continuous outcomes) and Table 5 (dichotomous outcomes) broken down by proprioceptive test subtype.

Table 4.

Comparison of proprioceptive impairments between UN+ and UN− (continuous outcomes).

| Study | Proprioception outcome | UN+ | UN− | Hedge’s g | Impaired group (effect size) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | ||||

| Movement detection | |||||||

| Meyer et al.62 | Em-NSA (median, IQR) | 7.0 (2.0–8.0) | 27 | 8.0 (7.0–8.0) | 95 | UTD | UN+ (p < 0.05)a |

| TFT Score (0–3) (median, IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 27 | 0 (0–1.0) | 95 | UTD | UN+ (p < 0.05)a | |

| Schmidt et al.63 | Arm Position Test–Error | 7.5 (1.0) | 7.0 | 4.5 (0.6) | 15 | 3.88 | UN+ (large) |

| Joint position matching | |||||||

| Borde et al.61 | Reproduction Error n – paretic upper limb | 7.8 (2.5) | 6 | 5 (5) | 3 | 0.73 | UN+ (medium) |

| Reproduction Error n – healthy upper limb | 3.3 (3.5) | 6 | 1.7 (4.6) | 3 | 0.37 | UN+ (small) | |

| TFT Error | 7.5 (2.7) | 6 | 6.7 (2.9) | 3 | 0.26 | UN+ (small) | |

| Borde et al.60 | Reproduction Error Total n | 12.9 (7.7) | 10 | 9.8 (7.8) | 10b | 0.38 | UN+ (small) |

| Reproduction Error No Vision n | 7.2 (5.1) | 10 | 6.2 (5.4) | 10b | 0.18 | Nil | |

| Semrau et al.65 | TFT Score (0–3) | 1.3 (1.1) | 35 | 0.7 (0.9) | 123 | 0.63 | UN+ (medium) |

| Semrau et al.64 | Kinesthetic Score Vision (lower = better) | 3.9 (1.7) | 59 | 1.8 (1.2) | 222 | 1.59 | UN+ (large) |

| Kinesthetic Score No Vision (lower = better) | 4.3 (1.4) | 59 | 2.4 (1.3) | 222 | 1.43 | UN+ (large) | |

| Laterality | |||||||

| Baas et al.51 | Hand Laterality % Error | 25 (5) | 7 | 14 (3) | 15 | 2.85 | UN+ (large) |

| Coslett54 | Hand Laterality (L) % Error | 41.7 (13.5) | 3 | 6.7 (9.9) | 3 | 2.37 | UN+ (large) |

| Hand Laterality (R) % Error | 16.3 (9.1) | 3 | 7.3 (8.1) | 3 | 0.84 | UN+ (large) | |

| Vromen et al.59 | Hand Laterality % Error | 37.6 (21.5) | 12 | 14.1 (14.7) | 8 | 1.18 | UN+ (large) |

| Body axis / midline | |||||||

| Heilman et al.55 | Pointing to body midline–Midline Deviation | 8.8 (NR) | 5 | −1.2 (NR) | 5 | UTD | UTD |

| Richard et al.56 | Pointing to body midline–Midline Deviation | 9.4 (12.5) | 8 | 1.6 (1.8) | 8 | 0.83 | UN+ (large) |

| Saj et al.58 | Longitudinal Body Axis Translation Head | 2.3 (2.0) | 6 | −0.3 (1.4) | 6 | 1.39 | UN+ (large) |

| Longitudinal Body Axis Translation Trunk | 5.9 (5.8) | 6 | −0.5 (1.1) | 6 | 1.42 | UN+ (large) | |

| Longitudinal Body Axis Rotation Head | −4.6 (2.2) | 6 | −2.5 (1.5) | 6 | −1.03 | UN+ (large) | |

| Longitudinal Body Axis Rotation Trunk | −4.6 (3.3) | 6 | −2.3 (1.9) | 6 | −0.79 | UN+ (medium) | |

| Tosi et al.66 | Arm Bisection Task | 69.7 (11.7) | 7 | 67.3 (10.7) | 37 | 0.22 | UN+ (small) |

| Body topography | |||||||

| Di Vita et al.23 | Body topography % Error | 42.9 (27.5) | 7 | 16 (17.2) | 16 | 1.17 | UN+ (large) |

| Rousseaux et al.57 | Localisation – Total Deviation | 1.8 (11.4) | 9 | 0.2 (7.8) | 6 | 0.16 | Nil |

| Localisation – Left Point Deviation | 13.4 (13.2) | 9 | 4.5 (9.5) | 6 | 0.78 | UN+ (medium) | |

UN: unilateral neglect; UN+: participants with UN; UN−: participants without UN; SD: standard deviation; Em-NSA: Erasmus Modifications to the Nottingham Sensory Assessment; IQR: interquartile range; UTD: unable to determine; TFT: thumb finding test; L: left; R: right; NR: not reported.

Effect size determined using cut offs of 0.2 for small, 0.5 medium, and 0.8 large as reported by Lakens.49

More impaired group determined by p values in study due to median and IQR reporting.

Data reported for UN− group with right hemisphere damage only.

Table 5.

Comparison of proprioceptive impairments between UN+ and UN− (dichotomous outcomes).

| Study | Proprioception outcome | N + | N- | Odds ratio (95% CI) | More impaired group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | N | % | N | ||||

| Movement detection | |||||||

| Meyer et al.62 | Em-NSA | 48.1 | 27 | 15.8 | 95 | 4.95 (1.94–12.61) | UN+ |

| TFT (0–3) | 77.8 | 27 | 47.4 | 95 | 3.89 (1.44–10.49) | UN+ | |

| van Stralen et al.67 | RASP–Impaired | 100 | 9 | 25.7 | 35 | 53 (2.81–1001.40) | UN+ |

| Joint position matching | |||||||

| Semrau et al.65 | Robotic Arm Position Matching Task–Failure | 100 | 35 | 59 | 123 | 48.78 (2.92–813.68) | UN+ |

| Semrau et al.64 | Robotic Upper Limb Position Match–Impaired+/−vision | 85 | 59 | 38 | 222 | 9.12 (4.27–19.51) | UN+ |

| Laterality | |||||||

| van Stralen et al.67 | Bergen Laterality Test Total Failure | 25.7 | 9 | 11.1 | 35 | 2.21 (0.34–14.59) | Nil |

| Body topography | |||||||

| Cocchini et al.53 | Body Exploration Fluff Test–Impaired | 71.4 | 14 | 16.7 | 24 | 12.5 (2.57–60.70) | UN+ |

UN: unilateral neglect; UN+: participants with UN; UN−: participants without UN; CI: confidence interval; Em-NSA: Erasmus Modifications to the Nottingham Sensory Assessment; TFT: thumb finding test; RASP: Rivermead Assessment of Somatosensory Perception.

UN assessment

There were a total of 18 different assessment tools used to assess UN, with 12 studies23,51–54,56–61,63 using more than one outcome measure to assess UN (see Table 2). Nine studies53–56,58,60,62,63,67 used pen-and-paper tests alone to identify UN, and two studies51,66 used outcome measures that assessed personal neglect solely. Two studies59,61 used a combination of a pen-and-paper task with a self-reported measure of UN and an environmental observation task, respectively. Two studies64,65 used a behavioural assessment in isolation (the BIT), while two studies52,57 added a functional assessment of UN (the CBS) to pen-and-paper cancellation and bisection tasks.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

We found moderate risk of bias in the majority of studies that demonstrated that people with UN after stroke have more severe proprioceptive impairments than those without. The assessment of UN was commonly limited to pen-and-paper tests designed to capture peri-personal hemi-spatial UN with minimal usage of UN tests that assess the impact of UN on functional activities. Multiple subtypes of proprioception were impaired, including movement detection, joint position matching, and the judgement of laterality, body axes and body topography. Deficits in spatial orientation and exploration in UN may be due to the disruption of distributed cortical networks controlling attention anchored in an egocentric frame of reference.68 Importantly, this egocentric frame of reference depends extensively on proprioceptive, visual and vestibular inputs.69 The results of this review suggest that proprioceptive deficits may underlie the disruption to the egocentric reference frame contributing to other impairments seen in UN.

Proprioception assessment

Proprioception is a complex sensorimotor process, with multiple aspects that contribute to adequate motor function. The finding that multiple types of proprioceptive impairment are present in people with UN is important for two major reasons. First, despite its importance to function, the majority of Stroke Guidelines17,70–72 do not include any recommendations for assessment or treatment of proprioceptive deficits, and subsequently, it is absent from national audits of stroke rehabilitation. Thus, it is likely that proprioceptive impairments are not being assessed and subsequently treated in this population. Second, the standardised clinical tools to test proprioception such as the Erasmus Modification of the Nottingham Sensory Assessment and the Rivermead Assessment of Somatosensory Perception solely assess simple movement detection. These tools use an ordinal grading system, defining the patient’s proprioception as normal, impaired or absent (reducing sensitivity to change)31,32 and have no correlation with patient function and activity.73 In addition, over 75% of Australian physiotherapists and occupational therapists report using non-validated proprioception assessment tools.74 Thus, standardised clinical assessments of proprioception fail to capture multiple aspects of the sense and have limited clinical utility. Furthermore, it is unknown what aspects of proprioception are assessed in clinical practice.

UN assessment

The predominant bias of UN assessment to the visuospatial domain suggests that the processing of proprioceptive information is impaired in this type of UN. The studies in this review that did use assessments of other aspects of UN support the notion that proprioceptive information is also neglected in other domains of the condition. However, further evidence is required in order to draw conclusions about proprioceptive impairment outside the traditional definition of visuospatial UN.

This is relevant for two reasons. First, the tendency of researchers and clinicians to consider UN a visuospatial disorder alone means that rehabilitation targets impairments only in this domain and that proprioceptive deficits are rarely considered. Second, multiple issues such as poor reliability, lack of ability to detect change, and the allowance for compensation to skew results limit the usefulness of pen-and-paper assessments of UN.13,75 Moreover, these tests correlate weakly with functional outcomes,76 which is important given the negative impact of UN on patient functional capacity. Also, the use of pen-and-paper assessments fails to capture a subset of patients with milder presentations of UN, which still likely contribute to functional deficits. However, in the acute stroke setting, there are more significant functional restrictions, and thus, these tests may be useful as a screening tool for UN at this stage. Where possible, assessment using an ecological tool such as the CBS would provide better insight on the impact of UN on function during the rehabilitation process. Importantly, only two included studies used the CBS, one rated as high and one as low on the AXIS scale.52,57 Thus, the presence of proprioception impairment in ecologically defined UN is largely unknown.

Proprioception and UN in clinical practice

The results of review suggest that higher levels of proprioceptive impairment could be a contributing factor in the poorer functional recovery seen in people with UN after stroke. However, despite being the most comprehensive tool available, the CBS does not directly measure the level of proprioceptive impairment present in UN. There is a clear need for a clinical assessment of UN that includes tests that are sensitive to impaired proprioception.

However, the clinical assessment of proprioception is currently inconsistent, frequently non-standardised and there is little data available on what constitutes a minimal clinically important difference (MCID). Importantly, assessment is typically focused solely on position detection. Thus, it is unsurprising that investigation of proprioceptive treatment often has a similar focus.77,78 Broadening the scope of clinical assessment to include multiple aspects of proprioception is likely to broaden the scope of investigation of treatment strategies. For example, recent studies using somatosensory stimulation (mostly neuromuscular electrical stimulation)79,80 to provide increased proprioceptive input show promising results in people after stroke. Improvements are thought to be due, in part, to the reintegration of the internal representations of the stimulated body parts. There is thus a clear need for a simple but comprehensive battery of proprioceptive tests to address the issues with clinical assessment of proprioception in general stroke populations. Once established, these tests could be incorporated into the clinical assessment of UN to enable identification of the multiple sensorimotor impairments present in this population.

Limitations of the study

Adopting a broad definition of proprioception is both a strength and limitation of this review. On one hand, the unification of multiple components of an essential sensorimotor process allows more functional, and thus clinically relevant, conclusions to be drawn. However, it also limits the strength of the conclusions of this review, due to the heterogeneity in data. This is a strong argument for further research in UN that comprehensively defines proprioception.

A further limitation of this review is the small sizes of the UN+ groups in the included studies (mean = 13 SD = ±14, range = 3–59). Eight studies with a collective sample size of 504 participants were excluded at full-text review due to insufficient reporting of data. All authors were contacted to request data, but the data were either unavailable or no reply was received. The inclusion of these data may change the strength of or the findings of the present review. In addition, the data of this review come from studies with a predominately moderate risk of bias which limits the strength of the conclusions.

Finally, heterogeneity of studies and the reporting of data did not allow for meta-analysis. There is a clear need to establish consensus on standard assessments of both UN and proprioception in research and clinical settings to reduce heterogeneity, which would allow stronger conclusions in future reviews.

Conclusion

We found that people with UN after stroke are more likely to have impaired processing of proprioceptive information than those without UN. These impairments occur across a variety of different subtypes of UN and aspects of proprioception. Assessment of both UN and proprioception is highly inconsistent, which likely reflects current clinical practice. Future investigations in this area should prioritise comprehensive and functional assessments of UN that include an assessment of proprioception.

Clinical messages

- In UN after stroke:

- Proprioceptive impairment is likely common and should be specifically assessed.

- Proprioceptive impairment can present in multiple ways, including (but not limited to) deficits in movement detection and position matching but also in body representation.

- Assessment of both UN and proprioception is frequently non-comprehensive, which likely reflects clinical practice.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, Appendices for Proprioceptive impairment in unilateral neglect after stroke: A systematic review by Georgia Fisher, Camila Quel de Oliveira, Arianne Verhagen, Simon Gandevia and David Kennedy in SAGE Open Medicine

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge associate professor Kris Rogers for his help in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Georgia Fisher  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7252-7800

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7252-7800

Camila Quel de Oliveira  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3991-0699

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3991-0699

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Wee JY, Hopman WM. Comparing consequences of right and left unilateral neglect in a stroke rehabilitation population. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 87(11): 910–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen P, Chen CC, Hreha K, et al. Kessler Foundation Neglect Assessment Process uniquely measures spatial neglect during activities of daily living. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015; 96(5): 869–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ringman JM, Saver JL, Woolson RF, et al. Frequency, risk factors, anatomy, and course of unilateral neglect in an acute stroke cohort. Neurology 2004; 63(3): 468–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowen A, McKenna K, Tallis RC. Reasons for variability in the reported rate of occurrence of unilateral spatial neglect after stroke. Stroke 1999; 30(6): 1196–1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hammerbeck U, Gittins M, Vail A, et al. Spatial neglect in stroke: identification, disease process and association with outcome during inpatient rehabilitation. Brain Sci 2019; 9(12): 374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cherney LR, Halper AS, Kwasnica CM, et al. Recovery of functional status after right hemisphere stroke: relationship with unilateral neglect. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82(3): 322–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jehkonen M, Laihosalo M, Kettunen JE. Impact of neglect on functional outcome after stroke – a review of methodological issues and recent research findings. Restor Neurol Neurosci 2006; 24(4–6): 209–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Di Monaco M, Schintu S, Dotta M, et al. Severity of unilateral spatial neglect is an independent predictor of functional outcome after acute inpatient rehabilitation in individuals with right hemispheric stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92(8): 1250–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bosma MS, Nijboer TCW, Caljouw MAA, et al. Impact of visuospatial neglect post-stroke on daily activities, participation and informal caregiver burden: a systematic review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2020; 63: 344–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karnath H-O, Rennig J, Johannsen L, et al. The anatomy underlying acute versus chronic spatial neglect: a longitudinal study. Brain 2011; 134(Pt 3): 903–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cherney L, Halper A. Unilateral visual neglect in right-hemisphere stroke: a longitudinal study. Brain Inj 2001; 15(7): 585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nijboer TCW, Kollen BJ, Kwakkel G. Time course of visuospatial neglect early after stroke: a longitudinal cohort study. Cortex 2013; 49(8): 2021–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Menon A, Korner-Bitensky N. Evaluating unilateral spatial neglect post stroke: working your way through the maze of assessment choices. Top Stroke Rehabil 2004; 11(3): 41–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Plummer P, Morris ME, Dunai J. Assessment of unilateral neglect. Phys Ther 2003; 83(8): 732–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vahlberg B, Hellström K. Treatment and assessment of neglect after stroke – from a physiotherapy perspective: a systematic review. Adv Physiother 2008; 10(4): 178–187. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Azouvi P, Jacquin-Courtois S, Luauté J. Rehabilitation of unilateral neglect: evidence-based medicine. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2017; 60(3): 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Clinical guidelines for stroke management 2017. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Stroke Foundation Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith DV, Clithero JA, Rorden C, et al. Decoding the anatomical network of spatial attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci 2013; 110(4): 1518–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doricchi F, Tomaiuolo F. The anatomy of neglect without hemianopia: a key role for parietal-frontal disconnection? Neuroreport 2003; 14(17): 2239–2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He BJ, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, et al. Breakdown of functional connectivity in frontoparietal networks underlies behavioral deficits in spatial neglect. Neuron 2007; 53(6): 905–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heilman KM, Valenstein E, Watson RT. The what and how of neglect. Neuropsychol Rehabil 1994; 4(2): 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robertson IH, Halligan PW. Spatial neglect: a clinical handbook for diagnosis and treatment. Hove: Psychology Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Di Vita A, Palermo L, Piccardi L, et al. Body representation alterations in personal but not in extrapersonal neglect patients. Appl Neuropsychol 2017; 24(4): 308–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rode G, Pagliari C, Huchon L, et al. Semiology of neglect: an update. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2017; 60(3): 177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hillier S, Immink M, Thewlis D. Assessing proprioception: a systematic review of possibilities. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2015; 29(10): 933–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ingram LA, Butler AA, Gandevia SC, et al. Proprioceptive measurements of perceived hand position using pointing and verbal localisation tasks. PLoS ONE 2019; 14(1): e0210911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Longo MR, Azanon E, Haggard P. More than skin deep: body representation beyond primary somatosensory cortex. Neuropsychologia 2010; 48(3): 655–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shenton JT, Schwoebel J, Coslett HB. Mental motor imagery and the body schema: evidence for proprioceptive dominance. Neurosci Lett 2004; 370(1): 19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Razmus M. Body representation in patients after vascular brain injuries. Cogn Process 2017; 18(4): 359–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rousseaux M, Honoré J, Vuilleumier P, et al. Neuroanatomy of space, body, and posture perception in patients with right hemisphere stroke. Neurology 2013; 81(15): 1291–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winward CE, Halligan PW, Wade DT. The Rivermead Assessment of Somatosensory Performance (RASP): standardization and reliability data. Clin Rehabil 2002; 16(5): 523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stolk-Hornsveld F, Crow JL, Hendriks EP, et al. The Erasmus MC modifications to the (revised) Nottingham Sensory Assessment: a reliable somatosensory assessment measure for patients with intracranial disorders. Clin Rehabil 2006; 20(2): 160–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Proske U, Gandevia SC. The proprioceptive senses: their roles in signaling body shape, body position and movement, and muscle force. Physiol Rev 2012; 92(4): 1651–1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Welmer AK, von Arbin M, Murray V, et al. Determinants of mobility and self-care in older people with stroke: importance of somatosensory and perceptual functions. Phys Ther 2007; 87(12): 1633–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kenzie JM, Semrau JA, Hill MD, et al. A composite robotic-based measure of upper limb proprioception. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2017; 14(1): 114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009; 339: b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. The Cochrane Collaboration. Data extraction forms, 2019, https://dplp.cochrane.org/data-extraction-forms

- 38. Albert ML. A simple test of visual neglect. Neurology 1973; 23(6): 658–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wilson B, Cockburn J, Halligan P. Development of a behavioral test of visuospatial neglect. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1987; 68(2): 98–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Azouvi P. Functional consequences and awareness of unilateral neglect: study of an evaluation scale. Neuropsychol Rehabil 1996; 6(2): 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Richardson JK. The clinical identification of peripheral neuropathy among older persons. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002; 83(11): 1553–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Carey LM, Oke LE, Matyas TA. Impaired limb position sense after stroke: a quantitative test for clinical use. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77(12): 1271–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Walsh LD, Taylor JL, Gandevia SC. Overestimation of force during matching of externally generated forces. J Physiol 2011; 589(Pt 3): 547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wajon A. Recognise™ app for graded motor imagery training in chronic pain. J Physiother 2014; 60: 117. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, et al. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016; 6(12): e011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Greenland S, O’Rourke K. On the bias produced by quality scores in meta-analysis, and a hierarchical view of proposed solutions. Biostatistics 2001; 2(4): 463–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Juni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, et al. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 1999; 282(11): 1054–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bull C, Byrnes J, Hettiarachchi R, et al. A systematic review of the validity and reliability of patient-reported experience measures. Health Serv Res 2019; 54(5): 1023–1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol 2013; 4: 863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Szumilas M. Explaining odds ratios. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010; 19(3): 227–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Baas U, de Haan B, Grässli T, et al. Personal neglect – a disorder of body representation. Neuropsychologia 2011; 49(5): 898–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Barra J, Chauvineau V, Ohlmann T, et al. Perception of longitudinal body axis in patients with stroke: a pilot study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2007; 78(1): 43–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cocchini G, Beschin N, Jehkonen M. The Fluff Test: a simple task to assess body representation neglect. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2001; 11(1): 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Coslett HB. Evidence for a disturbance of the body schema in neglect. Brain Cogn 1998; 37(3): 527–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Heilman KM, Bowers D, Watson RT. Performance on hemispatial pointing task by patients with neglect syndrome. Neurology 1983; 33(5): 661–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Richard C, Honore J, Bernati T, et al. Straight-ahead pointing correlates with long-line bisection in neglect patients. Cortex 2004; 40(1): 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rousseaux M, Sauer A, Saj A, et al. Mislocalization of tactile stimuli applied to the trunk in spatial neglect. Cortex 2013; 49(10): 2607–2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saj A, Honoré J, Richard C, et al. Where is the ‘straight ahead’ in spatial neglect? Neurology 2006; 67(8): 1500–1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vromen A, Verbunt JA, Rasquin S, et al. Motor imagery in patients with a right hemisphere stroke and unilateral neglect. Brain Inj 2011; 25(4): 387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Borde C, Mazaux JM, Barat M. Defective reproduction of passive meaningless gestures in right brain damage: a perceptual disorder of one’s own body knowledge. Cortex 2006; 42(1): 8–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Borde C, Mazaux JM, Sicre C, et al. Troubles somatognosiques et lésions hémisphériques droites. Ann Readapt Med Phys 1997; 40(1): 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Meyer S, De Bruyn N, Lafosse C, et al. Somatosensory Impairments in the upper limb poststroke: distribution and association with motor function and visuospatial neglect. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2016; 30(8): 731–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schmidt L, Keller I, Utz KS, et al. Galvanic vestibular stimulation improves arm position sense in spatial neglect: a sham-stimulation-controlled study. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2013; 27(6): 497–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Semrau JA, Herter TM, Scott SH, et al. Vision of the upper limb fails to compensate for kinesthetic impairments in subacute stroke. Cortex 2018; 109: 245–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Semrau JA, Wang JC, Herter TM, et al. Relationship between visuospatial neglect and kinesthetic deficits after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2015; 29(4): 318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Tosi G, Romano D, Maravita A. Mirror box training in hemiplegic stroke patients affects body representation. Front Hum Neurosci 2017; 11: 617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. van Stralen HE, Dijkerman HC, Biesbroek JM, et al. Body representation disorders predict left right orientation impairments after stroke: a voxel-based lesion symptom mapping study. Cortex 2018; 104: 140–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Corbetta M, Shulman GL. Spatial neglect and attention networks. Annu Rev Neurosci 2011; 34: 569–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nico D, Daprati E. The egocentric reference for visual exploration and orientation. Brain Cogn 2009; 69(2): 227–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. National stroke audit – rehabilitation services report 2018. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Stroke Foundation, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 71. National clinical guideline for stroke. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 72. Canadian stroke best practices: rehabilitation. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Meyer S, Karttunen AH, Thijs V, et al. How do somatosensory deficits in the arm and hand relate to upper limb impairment, activity, and participation problems after stroke? A systematic review. Phys Ther 2014; 94(9): 1220–1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Pumpa LU, Cahill LS, Carey LM. Somatosensory assessment and treatment after stroke: an evidence-practice gap. Aust Occup Ther J 2015; 62(2): 93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bonato M. Neglect and extinction depend greatly on task demands: a review. Front Hum Neurosci 2012; 6: 195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Nijboer TCW, Van Der Stigchel S. Visuospatial neglect is more severe when stimulus density is large. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 2019; 41(4): 399–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lynch EA, Hillier SL, Stiller K, et al. Sensory retraining of the lower limb after acute stroke: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88(9): 1101–1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Carey LM, Matyas TA. Training of somatosensory discrimination after stroke: facilitation of stimulus generalization. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2005; 84(6): 428–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kattenstroth JC, Kalisch T, Sczesny-Kaiser M, et al. Daily repetitive sensory stimulation of the paretic hand for the treatment of sensorimotor deficits in patients with subacute stroke: RESET, a randomized, sham-controlled trial. BMC Neurol 2018; 18(1): 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tashiro S, Mizuno K, Kawakami M, et al. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation-enhanced rehabilitation is associated with not only motor but also somatosensory cortical plasticity in chronic stroke patients: an interventional study. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. Epub ahead of print 20 November 2019. DOI: 10.1177/2040622319889259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, Appendices for Proprioceptive impairment in unilateral neglect after stroke: A systematic review by Georgia Fisher, Camila Quel de Oliveira, Arianne Verhagen, Simon Gandevia and David Kennedy in SAGE Open Medicine