Abstract

We investigated potential differential impact of barriers to HIV care retention among women relative to men. Client intake, health assessment, service, and laboratory information among clients receiving medical case management during 2017 in the Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program (RWP) were obtained and linked to American Community Survey data by ZIP code. Cross-classified multilevel logistic regression analysis was conducted. Among 1609 women and 5330 men, 84.6% and 83.7% were retained in care. While simultaneously controlling for all demographic characteristics, vulnerable/enabling factors, and neighborhood indices in the model, younger age, being US born, not working, and having a medical provider with low volume (<10) of clients remained associated with non-retention in care among women and men; while having ≥3 minors in the household and being perinatally infected were additionally associated with retention only for women. Both gender-specific and gender-non-specific barriers should be considered in efforts to achieve higher retention rates.

Keywords: HIV, care retention, women

What Do We Already Know about This Topic?

In the United States, women living with HIV are more likely to belong to racial/ethnic minority groups, have lower socioeconomic status, and more competing needs such as childcare than men, potentially affecting HIV care outcomes.

How Does Your Research Contribute to the Field?

We identified that if client health care providers cared for few Ryan White Program clients, retention was lower among both men and women, but that having 3 or more minors in the household was significantly associated with lower retention only for women.

What Are Your Research’s Implications toward Theory, Practice, or Policy?

Findings from our study indicate that the Ryan White Programs should assess patient retention outcomes among providers, particularly those with low volumes of clients, to identify providers in need of additional support and that the Ryan White Program should provide support for clients with childcare burdens.

Introduction

Women are a minority group among people living with HIV (PWH), making up about 25% of PWH in the US,1 and their needs related to HIV care, including HIV care retention, have been understudied relative to men. While the percentage of women retained in care in the US is similar to men (58%),2 women likely face different barriers to care due to demographic differences.3 For example, relative to men with HIV, women with HIV are more likely to be non-Hispanic Black or Hispanic,1 have lower socioeconomic status,3 and have lower educational levels.3 These factors have all been associated with lower rates of HIV care engagement or adherence.4-9 Studies of women have found that psychosocial factors such as stigma,10-12 lack of family support,13 and lack of transportation,10,14 and lack of disclosure10,15 were also associated with poor care engagement among women. However, the relative importance of specific barriers to HIV care retention among women compared to men has not been systematically assessed. HIV care retention is one of the steps of the HIV care continuum, and continuous retention is essential to long-term viral suppression success.6 The Ryan White Program provides medical care, medical case management, and support services to low-income PWH, serving as the provider of last resort for over half of the PWH in the US.16,17 This study examined people in the Part A and Part F’s Minority AIDS Initiative of Miami-Dade County’s Ryan White Program. Part A of the Ryan White Program provides medical and support services to counties and cities that are most severely affected by the HIV epidemic, and the Minority AIDS Initiative of Part F provides additional funding for these same services to address racial/ethnic disparities.17 The Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach metropolitan statistical area has the highest prevalence rate of diagnosed HIV in the US,18 and the Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program Part A and Minority AIDS Initiative, hereafter referred to as the RWP, serves about one sixth of all PWH in Miami-Dade County.18,19 To identify the most significant barriers to retention in the RWP among women relative to men, we conducted stratified cross-classified multilevel logistic regression analyses of RWP client intake, billing, laboratory, and neighborhood data.

Methods

Dataset/Population

Client intake, 2016 and 2017 health assessment, 2017 laboratory and 2017 service billing data files from the Miami-Dade County RWP were merged. Together these data included demographic, psychosocial, and health status factors, as well as viral load and CD4 laboratory data. To identify client needs, health assessments are conducted twice a year by medical case managers, who enter the data through a mixture of checking boxes and entering text into text fields. During the health assessments, case managers ask clients who their HIV provider is and about the client’s HIV-related symptoms, hospitalizations, medications, adherence, and any medical needs. They also ask clients about their employment, household structure, substance use, mental health symptoms, and needs related to housing, transportation, and food. Data from the first health assessment during 2017 was used. If there was no health assessment during 2017, the last health assessment from 2016 was used.

The study population included clients ≥18 years, enrolled in the RWP prior to January 2017, and who had received medical case management or peer services during 2017. Clients were excluded from the analysis if during 2017 they died, moved out of the county, were incarcerated, were dropped from the RWP because of no contact for at least 240 days, or became financially ineligible for the RWP. There were 6939 clients who met the inclusion criteria for the analyses.

Dependent Variable: Retention in Care

Retention in care was defined as evidence of at least 2 encounters with an HIV provider during 2017 that were at least 3 months apart, consistent with the Center for Disease Control’s (CDC) definition.2 Evidence included a service billed from a prescribing HIV provider or a HIV viral load or CD4 count test. About 14% of RWP clients receive the HIV care through a health insurance plan that is part of the Affordable Care Act marketplace; the RWP pays the premiums for this plan in lieu of paying providers directly. The RWP pays providers directly for the remaining clients. Because there is no service data available for clients who are in Affordable Care Act insurance plans, retention could be measured in those clients only through evidence of obtaining a HIV viral load or CD4 count test which would have been ordered by a provider. Thus, these laboratory test dates are used as a proxy for an HIV care visit consistent with how the CDC has defined retention.2

Independent, Individual-Level Variables

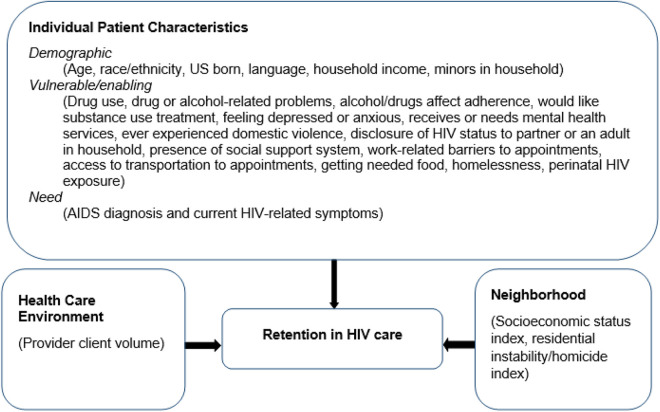

Our selection of independent variables was limited to those in the RWP dataset and informed by the Andersen Behavioral Model for Health Services Utilization20 adapted for HIV by Christopoulos et al.21 and Ulett et al.22 In this framework, health service seeking behaviors are driven by demographic, vulnerable, enabling, and need characteristics as well as the health care and external environment. Our adaptation of the framework and the variables considered are in Figure 1. Race and ethnicity variables from the original dataset were combined to form 4 categories: Hispanic (of any race), Haitian, Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) (excluding Hispanic Blacks and Haitian Blacks), and Non-Hispanic White/ Other (NHW). For 18 people that reported both Haitian and Hispanic ethnicity, the category was chosen based on preferred language. If ethnicity was not consistent with preferred language (n = 13) (e.g. Hispanic ethnicity but Creole as preferred language), race/ethnicity was assigned based on language and country of birth. People were classified as US-born if they were born in any of the 50 states. Non US-born included people born in another country and people born in US territories. Clients were asked at the time of the health assessments and during intake the name of their HIV care provider and also the name of the provider who prescribed each of their antiretroviral medications. These names were coded. Each person in the database was assigned a provider code for the purposes of analysis based on whom they named. If multiple providers were named, the following ranking was used: 1) HIV care provider at time of the first health assessment of 2017; 2) provider named during intake; and 3) provider named who prescribed HIV medications. If the client could provide no names of their HIV provider, the provider was coded as “unknown.” The total number of RWP clients for each HIV care provider was calculated, and this number was assigned to all clients with that assigned provider.

Figure 1.

HIV care retention and adapted behavioral model for vulnerable populations and associated variables. Figure based on Andersen Behavioral Model for Health Services Utilization20 adapted for HIV by Christopoulos et al.21 and Ulett et al.22

Neighborhood-Level Indices

Five-year estimates (2013–2017) of 25 neighborhood variables were obtained from the American Community Survey (ACS)23 for each zone improvement plan (ZIP) code tabulation area (ZCTA) (See Supplementary Table 1). The number of homicides for each ZIP code in Miami-Dade County was obtained from Simple Analytics.24 Due to the large number of neighborhood variables, we created indices by first conducting a reliability analysis and selecting variables to retain based on the Cronbach’s alpha if the item was deleted. Next, we conducted exploratory factor analysis without and with varimax rotation to select the number of factors and assess factor loadings. Variables with factor loadings <0.4 were removed.25 Finally, we performed confirmatory factor analysis to calculate individual scores on each of the indices for individuals in our dataset. Scores were computed as the linear combination of the standardized values of the variables in each factor.

The Cronbach’s alpha for all 25 neighborhood variables was 0.8084. Deleting 8 variables improved the Cronbach’s alpha to 0.9386. Factor analysis revealed 2 factors: low socioeconomic status (loadings ranged between 0.45 and 0.93), and residential instability/homicide (loadings were 0.66 and 0.72). The resulting index score for each ZCTA was merged to the RWP dataset by the client’s residential ZIP code.

Analysis

The demographic, need, vulnerable/enabling variables, and neighborhood indices were compared between men and women and between those who were and were not retained in care using chi-square tests for categorical variables and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for continuous variables. Cross-classified multilevel logistic regression models (CCMM) were generated using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS Version 9.4,26 using non-retention in care as the dependent variable and all variables considered in the bivariate analysis as independent variables. The 2 cross-classified variables were residential ZIP code and medical case management sites. Unlike traditional multilevel models where individuals are nested within hierarchical groups, CCMMs allow individuals in the same level to simultaneously belong to multiple non-hierarchical groups.27 Clients in the RWP dataset could belong to the same or different medical case management site (group 1) and reside in the same or different neighborhood (group 2). Models were run separately for men and women, followed by combining records and assessing for interactions for gender with all variables that were significant in either gender-stratified model. We used listwise deletion to handle missing data due to the small number of subjects who had one or more variables with missing values: 19 (0.4%) among men and 3 (0.2%) among women. Collinearity was assessed between all variables in each of the models, and preferred language was removed from the model because it was highly correlated with race/ethnicity and US born (Spearman correlation 0.87 and 0.76 respectively) and based on the type II tolerance (<0.1).

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

This study was approved by the Florida International University which waived the requirement for informed consent given the use of retrospective, anonymized data in this non-interventional study.

Results

Of the 6939 people in the dataset, 1609 (23.2%) were women, and 5330 (76.8%) were men. Relative to men, women were more likely to be older, NHB or Haitian, US born, have a preferred language of English or Haitian Creole, lower household income, more minors in the household, previous diagnoses with AIDS, HIV-related symptoms at the time of assessment, and live in a poor neighborhood (Table 1). However, the majority of women and men were not US born, did not have any minors in the household, had not been diagnosed with AIDS and had no HIV-related symptoms at the time of the assessment.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Clients of the Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program by Gender, 2017.

| Characteristics | Total, n | Women, n (%) | Men, n (%) | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 6939 | 1609 | 5330 | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age group (years) | ||||

| 18–34 | 1561 | 250 (15.5) | 1311 (24.6) | <0.0001 |

| 35–49 | 2666 | 603 (37.5) | 2063 (38.7) | |

| ≥ 50 | 2712 | 756 (47.0) | 1956 (36.7) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1731 | 668 (41.5) | 1063 (19.9) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 3989 | 486 (30.2) | 3503 (65.7) | |

| Haitian | 747 | 397 (24.7) | 350 (6.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic White/Other | 472 | 58 (3.6) | 414 (7.8) | |

| Born in USb | ||||

| Yes | 2311 | 701 (43.6) | 1610 (30.2) | <0.001 |

| No | 4628 | 908 (56.4) | 3720 (69.8) | |

| Preferred language | ||||

| English | 3007 | 827 (51.4) | 2180 (40.9) | <0.0001 |

| Spanish | 3217 | 413 (25.7) | 2804 (52.6) | |

| Haitian Creole | 626 | 350 (21.8) | 276 (5.2) | |

| All other | 89 | 19 (1.2) | 70 (1.3) | |

| Household income, percent of Federal Poverty Level | ||||

| ≥200% | 1594 | 202 (12.6) | 1392 (26.1) | <0.0001 |

| 100%–199% | 2414 | 572 (35.6) | 1842 (34.6) | |

| <100% | 2931 | 835 (51.9) | 2096 (39.3) | |

| Number of minors in household | ||||

| None | 6212 | 1153 (71.7) | 5059 (94.9) | <0.0001 |

| 1 | 427 | 248 (15.4) | 179 (3.4) | |

| 2 | 205 | 137 (8.5) | 68 (1.3) | |

| 3 or more | 95 | 71 (4.4) | 24 (0.5) | |

| Need characteristics | ||||

| Diagnosis of AIDS at any time | ||||

| Yes | 2840 | 795 (49.4) | 2045 (38.4) | <0.0001 |

| No | 4099 | 814 (50.6) | 3285 (61.6) | |

| Has HIV-related symptoms at time of assessment | ||||

| Yes | 137 | 42 (2.6) | 95 (1.8) | 0.0364 |

| No | 6802 | 1567 (97.4) | 5235 (98.2) | |

| Vulnerable/enabling variables | ||||

| Drug use in the last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 531 | 99 (6.2) | 432 (8.1) | 0.0098 |

| No | 6408 | 1510 (93.9) | 4898 (91.9) | |

| Drug use resulted in problems with daily activities or legal issue or hazardous situation | ||||

| Yes | 163 | 47 (2.9) | 116 (2.2) | 0.0839 |

| No | 6776 | 1562 (97.1) | 5214 (97.8) | |

| Drug use affects adherence | ||||

| Yes | 355 | 57 (3.5) | 298 (5.6) | 0.0011 |

| No | 6584 | 1552 (96.5) | 5032 (94.4) | |

| Would like substance use treatment now | ||||

| Yes | 112 | 36 (2.2) | 76 (1.4) | 0.0236 |

| No | 6827 | 1573 (97.8) | 5254 (98.6) | |

| Feeling depressed or anxious | ||||

| Yes | 1047 | 289 (18.0) | 758 (14.2) | 0.0002 |

| No | 5890 | 1320 (82.0) | 4570 (85.8) | |

| Receives or needs mental health services | ||||

| Yes | 1106 | 310 (19.3) | 796 (15.0) | <0.0001 |

| No | 5826 | 1299 (80.7) | 4527 (85.0) | |

| Ever experienced domestic violence | ||||

| Yes | 308 | 134 (8.3) | 174 (3.3) | <0.0001 |

| No | 6628 | 1475 (91.7) | 5153 (96.7) | |

| Disclosure of HIV status to partner or an adult in households | ||||

| No adult in household and no partner | 2605 | 540 (33.6) | 2065 (38.7) | <0.0001 |

| At least 1 adult in household or partner, but partner and adult do not know status | 595 | 203 (12.6) | 392 (7.4) | |

| Adult in household or a partner knows status | 3739 | 866 (53.8) | 2873 (53.9) | |

| Has a social support system to depend on | ||||

| No | 1217 | 234 (14.5) | 983 (18.5) | 0.0003 |

| Yes | 5721 | 1375 (85.5) | 4346 (81.6) | |

| Work-related barriers to attending care appointments | ||||

| Not working | 2764 | 825 (51.3) | 1939 (36.4) | <0.0001 |

| No | 4009 | 735 (45.7) | 3274 (61.4) | |

| Yes | 166 | 49 (3.1) | 117 (2.2) | |

| Client has access to transportation to appointments | ||||

| No | 634 | 127 (7.9) | 507 (9.5) | 0.0482 |

| Yes | 6305 | 1482 (92.1) | 4823 (90.5) | |

| Client getting food he/she needs | ||||

| No | 117 | 22 (1.3) | 96 (1.8) | 0.1757 |

| Yes | 6822 | 1588 (98.7) | 5234 (98.2) | |

| Homeless | ||||

| Yes | 378 | 76 (4.7) | 302 (5.7) | 0.1443 |

| No | 6561 | 1533 (95.3) | 5028 (94.3) | |

| Infected perinatally with HIV | ||||

| Yes | 49 | 24 (1.5) | 25 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| No | 6890 | 1585 (98.5) | 5305 (99.5) | |

| Health care environment | ||||

| Number of Ryan White clients that client’s clinician cares for | ||||

| 1–9 | 209 | 70 (4.4) | 139 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| 10–29 | 245 | 64 (4.0) | 181 (3.4) | |

| 30–99 | 1371 | 426 (26.5) | 945 (17.7) | |

| 100–199 | 2046 | 510 (31.7) | 1536 (28.8) | |

| ≥200 | 2666 | 444 (27.6) | 2222 (41.7) | |

| Unknownc | 402 | 95 (5.9) | 307 (5.8) | |

| Neighborhood environment | ||||

| Neighborhood low socioeconomic status (SES) indexd | ||||

| Median | 0.90 | 0.34 | <0.0001 | |

| Interquartile range | (0.34;1.51) | (−0.21;1.34) | ||

| Neighborhood residential instability/homicide indexe | ||||

| Median | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.0227 | |

| Interquartile range | (−0.29;0.93) | (−0.32;1.28) | ||

Percentages in the table represent column percentages.

Results exclude missing values as follows: feeling depressed or anxious (n = 2), receives or needs mental health services (n = 7), experienced domestic violence (n = 3), social support needs (n = 1) and the 2 neighbor indices (n = 15).

a Chi square for P values, Wilcoxon Rank Sum test for neighborhood indices.

b Those born in Puerto Rico or other US territories are classified as non-US born.

c Client who could not name provider during health assessment or patient intake.

d Higher score indicates lower SES.

e Higher score indicates more instability and homicides.

Of the 6939 people, 5823 (83.9%) were retained in HIV care during 2017, and there was no significant difference between women and men (84.6 vs. 83.7%; P = .40), (data not shown). Table 2 depicts the distribution of each variable by retention in care.

Table 2.

Non-Retention in HIV Care by Characteristics for Women and Men, Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program, 2017.

| Characteristics | Women (n = 1609) | Men (n = 5330) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retained in care, n (%) | Not retained in care, n (%) | P-valuea | Retained in care, n (%) | Not retained in care, n (%) | P-valuea | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | ||||||

| 18–34 | 185 (74.0) | 65 (26.0) | <0.0001 | 1038 (79.2) | 273 (20.8) | <0.0001 |

| 35–49 | 512 (84.9) | 91 (15.1) | 1738 (84.3) | 325 (15.8) | ||

| ≥ 50 | 664 (87.8) | 92 (12.2) | 1686 (86.2) | 270 (13.8) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 547 (81.9) | 121 (18.1) | 0.0129 | 792 (74.5) | 271 (25.5) | <0.0001 |

| Hispanic | 419 (86.2) | 67 (13.8) | 3029 (86.5) | 474 (13.5) | ||

| Haitian | 350 (88.2) | 47 (11.8) | 300 (85.7) | 50 (14.3) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White/Other | 45 (77.6) | 13 (22.4) | 341 (82.4) | 73 (17.6) | ||

| US-born | ||||||

| Yes | 554 (79.0) | 147 (21.0) | <0.0001 | 1225 (76.1) | 385 (23.9) | <0.0001 |

| No | 807 (89.0) | 101 (11.1) | 3237 (87.0) | 483 (13.0) | ||

| Preferred language | ||||||

| English | 665 (80.4) | 162 (19.6) | <0.0001 | 1695 (77.8) | 485 (22.3) | <0.0001 |

| Spanish | 368 (89.1) | 45 (10.9) | 2468 (88.0) | 336 (12.0) | ||

| Haitian Creole | 312 (89.1) | 38 (10.9) | 242 (87.7) | 34 (12.3) | ||

| All other | 16 (84.2) | 3 (15.8) | 57 (81.4) | 13 (18.6) | ||

| Household income, percent of Federal Poverty Level | ||||||

| ≥200% | 171 (84.7) | 31 (15.4) | 0.0730 | 1214 (87.2) | 178 (12.8) | <0.0001 |

| 100%–199% | 499 (87.2) | 73 (12.8) | 1597 (86.7) | 245 (13.3) | ||

| <100% | 691 (82.8) | 144 (17.3) | 1651 (78.8) | 445 (21.2) | ||

| Number of minors in household | ||||||

| None | 986 (85.5) | 167 (14.5) | 0.0174 | 4230 (83.6) | 829 (16.4) | 0.8148 |

| 1 | 211 (85.1) | 37 (14.9) | 152 (84.9) | 27 (15.1) | ||

| 2 | 113 (82.5) | 24 (17.5) | 59 (86.8) | 9 (13.2) | ||

| 3 or more | 51 (71.8) | 20 (28.2) | 21 (87.5) | 3 (12.5) | ||

| Need characteristics | ||||||

| Diagnosis of AIDS at any time | ||||||

| Yes | 663 (83.4) | 132 (16.6) | 0.1912 | 1716 (83.9) | 329 (16.1) | 0.7584 |

| No | 698 (85.8) | 116 (14.3) | 2746 (83.6) | 539 (16.4) | ||

| Has HIV-related symptoms | ||||||

| Yes | 31 (73.8) | 11 (26.2) | 0.05 | 60 (63.2) | 35 (36.8) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1330 (84.9) | 237 (15.1) | 4402 (84.1) | 833 (15.9) | ||

| Vulnerable/enabling variables | ||||||

| Drug use in the last 12 months | ||||||

| Yes | 69 (69.7) | 30 (30.3) | <0.0001 | 307 (71.1) | 125 (28.9) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1292 (85.6) | 218 (14.4) | 4155 (84.8) | 743 (15.2) | ||

| Drug use resulted in problems with daily activities or legal issue or hazardous situation | ||||||

| Yes | 28 (59.6) | 19 (40.4) | <0.0001 | 70 (60.3) | 46 (39.7) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1333 (85.3) | 229 (14.7) | 4392 (84.2) | 822 (15.8) | ||

| Drug use affect adherence or not | ||||||

| Yes | 44 (77.2) | 13 (22.8) | 0.1155 | 221 (74.2) | 77 (25.8) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1317 (84.9) | 235 (15.1) | 4241 (84.3) | 791 (15.7) | ||

| Would like substance use treatment now | ||||||

| Yes | 19 (52.8) | 17 (47.2) | <0.0001 | 41 (54.0) | 35 (46.1) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1342 (85.3) | 231 (14.7) | 4421 (84.2) | 833 (15.9) | ||

| Feeling depressed or anxious | ||||||

| Yes | 239 (82.7) | 50 (17.3) | 0.3265 | 583 (76.9) | 175 (23.1) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1122 (85.0) | 198 (15.0) | 3877 (84.8) | 693 (15.2) | ||

| Receives or needs mental health services | ||||||

| Yes | 252 (81.3) | 58 (18.7) | 0.0736 | 618 (77.6) | 178 (22.4) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1109 (85.4) | 190 (14.6) | 3839 (84.8) | 688 (15.2) | ||

| Ever experienced domestic violence | ||||||

| Yes | 111 (82.8) | 23 (17.2) | 0.5577 | 133 (76.4) | 41 (23.6) | 0.0081 |

| No | 1250 (84.8) | 225 (15.3) | 4327 (84.0) | 826 (16.0) | ||

| Disclosure of HIV status to adults in households | ||||||

| No adults in household | 445 (82.4) | 95 (17.6) | 0.1551 | 1713 (83.0) | 352 (17.1) | 0.4832 |

| Adults in household, but none know status | 178 (87.7) | 25 (12.3) | 329 (83.9) | 63 (16.1) | ||

| At least 1 adult in household knows status | 738 (85.2) | 128 (14.8) | 2420 (84.2) | 453 (15.8) | ||

| Has a social support system to depend on | ||||||

| No | 189 (80.8) | 45 (19.2) | 0.0802 | 789 (80.3) | 194 (19.7) | 0.0011 |

| Yes | 1172 (85.2) | 203 (14.8) | 3673 (84.5) | 673 (15.5) | ||

| Work related barriers to attending care appointments | ||||||

| Not working | 671 (81.3) | 154 (18.7) | 0.0010 | 1479 (76.3) | 460 (23.7) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 43 (87.8) | 6 (12.2) | 101 (86.3) | 16 (13.7) | ||

| No | 647 (88.0) | 88 (12.0) | 2882 (88.0) | 392 (12.0) | ||

| Client has access to transportation to appointments | ||||||

| No | 101 (79.5) | 26 (20.5) | 0.0999 | 398 (78.5) | 109 (21.5) | 0.0008 |

| Yes | 1260 (85.0) | 222 (15.0) | 4064 (84.3) | 759 (15.7) | ||

| Client getting food he/she needs | ||||||

| No | 16 (76.2) | 5 (23.8) | 0.2834 | 57 (59.4) | 39 (40.6) | <0.0001 |

| Yes | 1345 (84.7) | 243 (15.3) | 4405 (84.2) | 829 (15.8) | ||

| Homeless | ||||||

| Yes | 52 (68.4) | 24 (31.6) | <0.0001 | 207 (68.5) | 95 (31.5) | <0.0001 |

| No | 1309 (85.4) | 224 (14.6) | 4255 (84.6) | 773 (15.4) | ||

| Infected perinatally with HIV | ||||||

| Yes | 12 (50.0) | 12 (50.0) | <0.0001 | 18 (72.0) | 7 (28.0) | 0.1118 |

| No | 1349 (85.1) | 236 (14.9) | 4444 (83.8) | 861 (16.2) | ||

| Health care environment | ||||||

| Number of Ryan White clients that client’s clinician cares for | ||||||

| 1–9 | 48 (68.6) | 22 (31.4) | <0.0001 | 92 (66.2) | 47 (33.8) | <0.0001 |

| 10–29 | 56 (87.5) | 8 (12.5) | 140 (77.4) | 41 (22.7) | ||

| 30–99 | 361 (84.7) | 65 (15.3) | 813 (86.0) | 132 (14.0) | ||

| 100–199 | 452 (88.6) | 58 (11.4) | 1293 (84.2) | 243 (15.8) | ||

| ≥200 | 375 (84.5) | 69 (15.5) | 1901 (85.6) | 321 (14.5) | ||

| Unknownc | 69 (72.6) | 26 (27.4) | 223 (72.6) | 84 (27.4) | ||

| Neighborhood environment | ||||||

| Neighborhood low socioeconomic status (SES) Indexd | ||||||

| Median | 0.88 | 1.04 | 0.3170 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.0327 |

| Interquartile range | (0.34, 1.51) | (0.33, 1.64) | (−0.21, 1.32) | (−0.21, 1.37) | ||

| Neighborhood residential instability/homicide indexe | ||||||

| Median | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.0043 | 0.41 | 0.65 | 0.4094 |

| Interquartile range | (−0.29, 0.89) | (−0.04, 1.28) | (−0.40, 1.28) | (−0.29, 1.28) | ||

Percentages in the table represent row percentages.

Results exclude missing values as follows: feeling depressed or anxious (n = 2), receives or needs mental health services (n = 7), experienced domestic violence (n = 3), social support needs (n = 1), and the 2 neighbor indices (n = 15).

aP-values from chi-square. For continuous variables median and interquartile range reported, P-value from Wilcoxon rank sum.

b Those born in Puerto Rico or other US territories are classified as non-US born.

c Clients who could not name HIV care provider during health assessment or patient intake.

d Higher score indicates lower SES.

e Higher score indicates more instability and homicides.

Cross-classified multilevel logistic regression models were generated using residential ZIP code and medical case management sites for men. For women, ZIP code random effects were not estimable for the full model due to the number of independent variables; therefore, the model ran as a multilevel model with medical case management group only. Demographic factors associated with non-retention in care among both men and women were younger age (women: being aged 18–34 relative to ≥35, men: age groups <50 relative to ≥50) and being US born (Table 3). For women only, having ≥3 minors in the household were associated with non-retention.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios of Non-Retention in HIV Care Among Miami-Dade County Ryan White Program Clients, 2017, Models Stratified for Women and Men.

| Women (N = 1606) | Men (N = 5311) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age group | ||||

| 18–34 | 1.98 | (1.27–3.09) | 1.86 | (1.50–2.32) |

| 35–49 | 1.35 | (0.95–1.93) | 1.42 | (1.18–1.72) |

| ≥50 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.81 | (0.39–1.67) | 1.38 | (0.99–1.91) |

| Hispanic | 1.17 | (0.53–2.60) | 0.99 | (0.72–1.38) |

| Haitian | 1.01 | (0.43–2.38) | 1.22 | (0.78–1.92) |

| Non-Hispanic White/Other | Ref | Ref | ||

| US-borna | ||||

| Yes | 2.11 | (1.30–3.43) | 1.34 | (1.06–1.70) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Household income, percent of Federal Poverty Level | ||||

| 200%- >300% | Ref | Ref | ||

| 100%–199% | 0.70 | (0.43–1.13) | 0.93 | (0.75–1.16) |

| <100% | 0.71 | (0.43–1.16) | 1.04 | (0.82–1.31) |

| Number of minors in household | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||

| 1 | 1.13 | (0.73–1.73) | 0.96 | (0.62–1.49) |

| 2 | 1.34 | (0.80–2.26) | 0.88 | (0.43–1.81) |

| 3 or more | 2.03 | (1.10–3.76) | 0.56 | (0.16–2.00) |

| Need characteristics | ||||

| Diagnosis of AIDS at any time | ||||

| Yes | 1.20 | (0.89–1.61) | 0.98 | (0.83–1.16) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Has HIV-related symptoms at time of assessment | ||||

| Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| No | 0.67 | (0.30–1.47) | 0.54 | (0.34–0.86) |

| Vulnerable/enabling variables | ||||

| Drug use in the last 12 months | ||||

| Yes | 1.18 | (0.42–3.33) | 1.22 | (0.78–1.90) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Drug use resulted in problems with daily activities or legal issue or hazardous situation | ||||

| Yes | 1.39 | (0.48–4.05) | 1.27 | (0.75–2.13) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Drug use affects adherence | ||||

| Yes | 0.77 | (0.28–2.13) | 0.96 | (0.59–1.54) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Would like substance use treatment now | ||||

| Yes | 2.25 | (0.91–5.54) | 1.57 | (0.89–2.76) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Feeling depressed or anxious | ||||

| Yes | 0.90 | (0.58–1.39) | 1.18 | (0.94–1.49) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Receives or needs mental health services | ||||

| Yes | 0.92 | (0.60–1.41) | 0.93 | (0.74–1.17) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Ever experienced domestic violence | ||||

| Yes | 0.71 | (0.40–1.24) | 0.97 | (0.64–1.46) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Disclosure of HIV status to partner or an adult in household | ||||

| Does not have a partner or adult in household | 1.34 | (0.97–1.84) | 1.13 | (0.95–1.34) |

| At least 1 adult in household or partner, but partner and adult do not know status | 1.03 | (0.63–1.67) | 0.98 | (0.73–1.33) |

| Adult in household or a partner knows status | Ref | Ref | ||

| Has a social support system to depend on | ||||

| No | 1.13 | (0.76–1.68) | 1.13 | (0.93–1.38) |

| Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| Work related barriers to attending care appointments | ||||

| Not working | 1.72 | (1.21–2.43) | 1.80 | (1.48–2.20) |

| Yes | 1.13 | (0.45–2.85) | 1.35 | (0.77–2.36) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Client has access to transportation to appointments | ||||

| No | 1.19 | (0.71–1.99) | 1.24 | (0.96–1.58) |

| Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| Client getting food he/she needs | ||||

| No | 1.53 | (0.51–4.64) | 1.98 | (1.24–3.14) |

| Yes | Ref | Ref | ||

| Homeless | ||||

| Yes | 1.30 | (0.67–2.53) | 1.32 | (0.98–1.78) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Infected perinatally with HIV | ||||

| Yes | 3.04 | (1.16–7.93) | 0.89 | (0.35–2.26) |

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Health care environment | ||||

| Number of Ryan White clients that client’s clinician cares for | ||||

| 1–9 | 1.91 | (1.03–3.56) | 2.89 | (1.93–4.30) |

| 10–29 | 0.63 | (0.27–1.46) | 1.57 | (1.06–2.33) |

| 30–99 | 1.10 | (0.74–1.65) | 1.02 | (0.80–1.29) |

| 100–199 | 0.66 | (0.44–1.00) | 1.24 | (0.99–1.54) |

| ≥200 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Unknownb | 1.41 | (0.79–2.51) | 2.08 | (1.52–2.85) |

| Neighborhood environment | ||||

| Neighborhood low socioeconomic status (SES) Index (higher score indicates lower SES) c | 1.00 | (0.82–1.23) | 0.94 | (0.85–1.04) |

| Neighborhood residential instability/homicide indexd | 1.12 | (0.92–1.36) | 0.98 | (0.90–1.07) |

The intercluster correlation coefficients were 0.047 for the same ZIP code and medical case management site, 0.016 for the same ZIP code and different medical case management site and 0.032 for a different ZIP code and same medical case management site.

Bold indicates statistically significant P < 0.05.

Results exclude19 men and 3 women with missing values from one or more of the following variables: feeling depressed or anxious, receives or needs mental health services, experienced domestic violence social support needs, and neighborhood indices.

a Those born in Puerto Rico or other US territories are classified as non-US born.

b Clients who could not name HIV care provider during health assessment or patient intake.

c Higher score indicates lower SES.

d Higher score indicates more instability and homicides.

None of the need characteristics were associated with retention among women. For men, having symptoms was associated with non-retention.

Regarding the vulnerable/enabling variables, not working was significantly associated with non-retention for both men and women. For women only, having been infected with HIV perinatally was significantly associated with non-retention. For men only, not getting needed food was significantly associated with non-retention.

Among both men and women, having a provider with <10 RWP patients compared with ≥200 was associated with non-retention. Among men only, compared with having a provider with ≥200 RWP patients, having a provider with 10–29 RWP patients or not knowing the provider’s name was additionally associated with non-retention. There was no association between neighborhood index and retention in care either among men or women. The only statistically significant interaction term between each of the variables and gender was perinatal HIV transmission where the association between perinatal infection and lower retention was significantly stronger for women than men (P = .03). There was no significant interaction between race/ethnicity and US birth.

Discussion

Men and women served by the Miami-Dade County RWP are demographically different, with women being older, more likely to be NHB and Haitian, English- and Creole- speaking, US born, having minors in the household, having a lower household income, and living in a poorer neighborhood. Despite having a higher prevalence of demographic and other factors that may be barriers to care such as having symptoms of depression and anxiety and history of experiencing domestic violence, women’s retention in HIV care was nearly identical to men (84.6 vs. 83.7% respectively). This is consistent with 2011 national RWP data indicating that retention in care for men and women is similar (82.9% for women and 82.0% for men).28 Our data did not have measures of resiliency or other factors that may be helping women be successful in care despite increased adversity relative to men. Such factors need to be explored.

In the bivariate analysis race/ethnicity was associated with non-retention in care with the highest proportion of non-retention for women among NHW/other women and for men among NHB men. However, in the regression models, there were no statistically significant odds ratios for race/ethnicity among men or women after adjustment for other demographic, need, vulnerable/enabling, and health care environment factors. National RWP 2011 data indicated that non-retention was significantly higher among NHBs (19.3%) than NHWs (17.5%), but in that study only a limited number of demographic factors were controlled for.28 In our study, NHB women had appreciably lower non-retention than NHB men (17.9% vs. 25.4%). Additionally, they had lower non-retention (17.9%) than NHW women (22.0%). Indeed, the only gender disparity was among NHWs in that women’s non-retention (22.0%) was substantially higher than that of NHW men (17.1%). A study of the North American AIDS Cohort Collaboration on Research and Design (NA-ACCORD), a consortium of more than 20 cohorts in the United States and Canada, found that after 5 years of entry into HIV care, NHW women had the lowest mean percentage of person-time in HIV care among all gender and racial/ethnic groups.29

Compared with NHWs, Hispanics and Haitians had higher retention in care in unadjusted analyses. To assess the relationship between race/ethnicity and US birth, we compared retention by US birth status stratified by sex and race/ethnicity in a post-hoc analysis (See Supplemental Table 2). We found that for all racial/ethnic groups, retention was higher for those non-US born than US born with differences being statistically significant for Hispanics and NHBs for men and women and Haitians among women. However, there were no significant interactions between race/ethnicity and US birth after adjusting for other variables. These findings suggest that immigrant populations in the RWP are not disadvantaged relative to US-born clients. However, these findings may not apply to other regions because Miami-Dade County has a high percentage of Hispanics (69.1%), people who do not speak English at home (73.8%), and people who are foreign-born (52.9%).30 Thus, in Miami-Dade County relative to other regions in the US, non-US born and non-English speaking people tend not to be isolated, and the local health care environment is more likely to have staff who are linguistically and culturally concordant with clients.

Women were much more likely to live with a minor in the household than men (28.3% vs 5.1% respectively), (data not shown). In the logistic regression model, there was a dose-dependent reduction in retention for women with increased number of minors in the household, although the association was only statistically significant when there were ≥3 minors in the household. This relationship was not seen in men. It was not possible to determine if these minors were cared for by the PWH or not, but the results suggest that caring for minors may be impacting retention among women. This is consistent with another study that found that having ≥ 2 children was associated with lower adherence to antiretroviral therapy among women.31

In the Andersen Behavioral Model for Health Services Utilization,20 need drives health care use. However, we found that having HIV-related symptoms was associated with non-retention, and not, as expected, with retention although the association was only significant for men. It is likely that those who are not retained are not receiving antiretroviral medications and thus having a non-suppressed viral load. Thus, in this situation, having HIV-related symptoms may not be the need driving use of care but rather the effect of not seeking care.

Not working was associated with not being retained in care for both men and women. This finding may seem counterintuitive because work competes with appointment attendance particularly for people with low paying jobs that do not offer sick leave. However, a meta-analysis found that employment was associated with a 27% increased likelihood of adherence to antiretroviral therapy,32 and 2 studies have reported a decreased likelihood of missed visits with employment.33,34 These findings may be confounded by factors related to employment such as education, organizational skills, self-esteem, or self-efficacy,34 which may empower clients to better manage their HIV care. However, we cannot rule out that the association is at least partly due to people who are in care and virally suppressed being healthier and able to work.

For both men and women, lack of food was associated with non-retention although the association was only significant for men. While the odds ratios suggested that homelessness was associated with non-retention for both men and women, the relationship was not significant, which may be due to the relatively small number of homeless people in our dataset. Unmet housing and food needs have been reported in other studies to adversely affect HIV care outcomes.35-38 There were small numbers of people reporting these needs; yet it may be difficult to appreciably increase HIV care retention among the minority of people not yet retained without addressing these needs. No measure of substance use was associated with retention in care which is not consistent with other studies.39 This may be due to the lack of validated measures of substance use that are used by the Ryan White Program system given their primary goal of identifying client service needs.

It is not clear why perinatal HIV exposure would be associated with retention in care in women but not men. Youth who were perinatally infected with HIV face special challenges to HIV care retention such as cognitive impairment, mental health problems, and treatment fatigue particularly when transitioning from pediatric to adult care.40 A study using national surveillance data found that retention was higher among females than males who were perinatally infected (64.2% vs. 57.6%) although the percentages included people younger than 18.41 However, our results with respect to differences in retention by gender should be interpreted with caution given the small number of participants who were perinatally exposed to HIV.

Compared to having a HIV clinician who cared for ≥200 RWP clients, men and women cared for by a HIV clinician with <10 RWP clients were less likely to be retained in care. Of note, we measured the number of RWP clients not HIV patients. Some of these low volume clinicians may have many HIV patients, but few RWP clients. Other studies indicate that clinical outcomes for PWH cared for by clinicians with a low volume of PWH or with less experience have worse outcomes relative to PWH cared for by clinicians with a high volume of PWH.42-44 These differences may be due to less experience by both the HIV health care provider and/or support staff, which may also increase the likelihood of patient-perceived HIV stigma), or to how the practices are set up or staffed. Compared with practices with fewer than 10 RWP clients, practices seeing many RWP clients are more likely to have support staff adept at dealing with the specific requirements of the RWP as well as the special needs of the clients. Clients in the RWP are free to choose the clinic site that they want to attend, and anecdotally many clients choose clinics and providers that are not near their homes because they like particular providers or the clinic sites. Thus, the high-volume providers may represent the most trusted providers. Unknown clinician (when a person doesn’t know the clinician’s name) was also associated with non-retention, although it was only significant for men. This may indicate a weaker relationship between the client and clinician which has been found to be associated with poorer engagement as measured by percentage of appointments kept.45

This study is subject to several limitations. It is a secondary analysis of administrative RWP data, which were collected and entered by multiple case managers from different medical case management systems. Differences in completeness and accuracy of information may occur due to variations in case managers’ interviewing skills, available time for each client, and data entry practices. Furthermore, the questions were asked to identify needed services for each patient and not for research purposes; thus, validated scales were not used. Finally, some variables were based on information that clients may be reluctant to share. Thus, it is likely that substance use and history of intimate partner violence were underreported. Furthermore, we had no information about stigma and little detail about family and social support—factors associated with retention in other studies.10,13,33,46 An additional limitation is that our analysis is restricted to clients who are engaged in care in that we only included people who had a health assessment. Thus, our results apply to people who have been linked to care and had at least one contact with the Ryan White Program. Furthermore, our analysis excluded clients who left the program for various reasons. Some of these reasons such as financial ineligibility (i.e. income increased) and extended incarceration (due to care provided in prison) would likely be associated with better retention, while others such as being dropped from the RWP because of no contact for at least 240 days may be associated with worse retention. The Ryan White Program data system is at the county level and does not allow for data linkages between counties within Florida or within states. Therefore, while some of those with no contact may be out of care, some also may be served by Ryan White Programs in neighboring counties. These limitations may be affecting the measured overall retention rate, but it is not clear or how they would be affecting the specific barriers that were identified or any differences between men and women. The neighborhood analysis was limited in that the geographic unit available for analysis was the ZIP code. An analysis by census tract would have allowed for a more precise characterization of the neighborhood. Finally, it was not possible to analyze client volume by providers in more depth with service data because service billing data was only available for clients who were not enrolled in Affordable Care Act insurance plans and the data frequently listed the provider as a site and not as a specific health care professional. Additionally, because of the limitations of the data, it was not possible to use additional retention measures such as missed visits or visit adherence. However, the retention measure we used has been found to have good prognostic value for viral suppression.47

Conclusions

Despite women living with HIV being generally more socioeconomically disadvantaged than men, HIV care retention was similar for men and women. For men and women, having a clinician who cares for few RWP patients appears to adversely affect care retention, suggesting the need to examine how such clinicians can be supported to better serve RWP clients. For example, RWPs could share best practices from highly experienced RWP providers with those providers with less RWP experience. Overall, 16% of enrolled clients were not retained in care; to reduce this number, addressing some of the identified problems such as lack of employment, food insecurity, and substance use will be needed. For women, being perinatally infected with HIV and caring for children appear to be additional barriers that need further examination.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental_Table_1_4.19.20 for Differential Role of Psychosocial, Health Care System and Neighborhood Factors on the Retention in HIV Care of Women and Men in the Ryan White Program by Mary Jo Trepka, Diana M. Sheehan, Rahel Dawit, Tan Li, Kristopher P. Fennie, Merhawi T. Gebrezgi, Petra Brock, Mary Catherine Beach and Robert A. Ladner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental_Table_2_7.11.20 for Differential Role of Psychosocial, Health Care System and Neighborhood Factors on the Retention in HIV Care of Women and Men in the Ryan White Program by Mary Jo Trepka, Diana M. Sheehan, Rahel Dawit, Tan Li, Kristopher P. Fennie, Merhawi T. Gebrezgi, Petra Brock, Mary Catherine Beach and Robert A. Ladner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Acknowledgments

We wish to gratefully acknowledge Carla Valle-Schwenk, Ryan White Program Administrator, and the entire Ryan White Part A Program in the Miami-Dade County Office of Management and Budget, for their active assistance, cooperation and facilitation in the implementation of this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is supported by Award Numbers R01MD013563 and in part by R01MD012421, U54MD012398 and K01MD013770 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities at the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD: Mary Jo Trepka  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6585-1194

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6585-1194

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Estimated HIV incidence and prevalence in the United States, 2010–2019. HIV Surv Suppl Rep. 2019;24(1). Published 2019 Accessed September 20, 2019 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Monitoring selected national HIV prevention and care objectives by using HIV surveillance data—United States and 6 US dependent areas. HIV Surv Suppl Rep. 2019;25(2). Accessed September 20, 2019 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beer L, Mattson CL, Bradley H, Skarbinski J. Understanding cross-sectional racial, ethnic, and gender disparities in antiretroviral use and viral suppression among HIV patients in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;95(13):e3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson AN, Higgins CM, Haardörfer R, Holstad MM, Nguyen MLT, Waldrop-Valverde D. Disparities in retention in care among adults living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(4):985–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen JK, Santos GM, Moss NJ, Coffin PO, Block N, Klausner JD. Regular clinic attendance in two large San Francisco HIV primary care settings. AIDS Care. 2016;28(5):579–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Colasanti J, Kelly J, Pennisi E, et al. Continuous retention and viral suppression provide further insights into the HIV care continuum compared to the cross-sectional HIV care cascade. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(5):648–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dasgupta S, Oster AM, Li J, Hall HI. Disparities in consistent retention in HIV care—11 States and the District of Columbia, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(4):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ghiam MK, Rebeiro PF, Turner M, et al. Trends in HIV continuum of care outcomes over ten years of follow-up at a large HIV primary medical home in the Southeastern United States. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33(10):1027–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hall HI, Gray KM, Tang T, Li J, Shouse L, Mermin J. Retention in care of adults and adolescents living with HIV in 13 U.S. areas. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(1):77–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giles ML, MacPhail A, Bell C, et al. The barriers to linkage and retention in care for women living with HIV in an high income setting where they comprise a minority group. AIDS Care. 2019;31(6):730–736. doi:10.1080/09540121.2019.1576843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McDoom MM, Bokhour B, Sullivan M, Drainoni M. How older black women perceive the effects of stigma and social support on engagement in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29(2):95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sangaramoorthy T, Jamison AM, Dyer TV. HIV stigma, retention in care, and adherence among older black women living with HIV. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2017;28(4):518–531. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Geter A, Sutton MY, Hubbard McCree D. Social and structural determinants of HIV treatment and care among black women living with HIV infection: a systematic review: 2005-2016. AIDS Care. 2018;30(4):409–416. doi:10.1080/09540121.2018.1426827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Magnus M, Herwehe J, Murtaza-Rossini M, et al. Linking and retaining HIV patients in care: the importance of provider attitudes and behaviors. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(5):297–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Loutfy M, Johnson M, Walmsley S, et al. The association between HIV disclosure status and perceived barriers to care faced by women living with HIV in Latin America, China, Central/Eastern Europe, and Western Europe/Canada. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30(9):435–444. doi:10.1089/apc.2016.0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bradley H, Viall AH, Wortley PM, Dempsey A, Hauck H, Skarbinski J. Ryan White HIV/AIDS program assistance and HIV treatment outcomes. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(1):90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health Resources and Service Administration. Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program Annual client-Level Data Report 2017. Published 2018 Accessed September 24, 2019 http://hab.hrsa.gov/data/data-reports

- 18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report. Vol. 31 Published 2020 Updated 2018 Accessed July 03, 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html [Google Scholar]

- 19. HIV/AIDS Partnership. 2019 Needs Assessment. Published 2019 Accessed September 20, 2019 http://aidsnet.org/partners/annual-needs-assessment/

- 20. Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Socl Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Christopoulos KA, Das M, Colfax GN. Linkage and retention in HIV care among men who have sex with men in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl_2):S214–S222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ulett KB, Willig JH, Lin H-Y, et al. The therapeutic implications of timely linkage and early retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(1):41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. American Community Survey. 2011–2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. American Community Survey United States Census Bureau; Published 2019 Accessed March 18, 2019 https://factfinder.census.gov [Google Scholar]

- 24. Simply Analytics. Simply Analytics Data. Published 2019 Accessed December 19, 2018 https://simplyanalytics.com/

- 25. Peterson RA. A meta-analysis of variance accounted for and factor loadings in exploratory factor analysis. Marketing Letters. 2000;11(3):261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 26. SAS Institute. SAS, Version 9.4. SAS Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Goldstein H. Multilevel cross-classified models. Sociol Methods Res. 1994;22(3):364–375. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Doshi RK, Milberg J, Isenberg D, et al. High rates of retention and viral suppression in the US HIV safety net system: HIV care continuum in the Ryan White HIV/AIDS Program, 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(1):117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Desir FA, Lesko CR, Moore RD, et al. One size fits (n)one: the influence of sex, age, and sexual human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition risk on racial/ethnic disparities in the HIV care continuum in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(5):795–80224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. US Census Bureau. Quick Facts 2013-2017 Miami-Dade County. Published 2019 Accessed December 05, 2019 https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/miamidadecountyflorida/POP815217

- 31. Merenstein D, Schneider MF, Cox C, et al. Association of child care burden and household composition with adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in the Women’s Interagency HIV Study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2009;23(4):289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Peltzer K, et al. Association between antiretroviral therapy adherence and employment status: systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2014;93(1):29–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hussen SA, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA, Hightow-Weidman LB; Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. Psychosocial influences on engagement in care among HIV-positive young black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(2):77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nijhawan AE, Liang Y, Vysyaraju K, et al. Missed initial medical visits: predictors, timing, and implications for retention in HIV care. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(5):213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aidala AA, Wilson MG, Shubert V, et al. Housing status, medical care, and health outcomes among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(1):e1–e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Arnold EA, Weeks J, Benjamin M, et al. Identifying social and economic barriers to regular care and treatment for black men who have sex with men and women (BMSMW) and who are living with HIV: a qualitative study from the Bruthas cohort. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bulsara SM, Wainberg ML, Newton-John TR. Predictors of adult retention in HIV care: a systematic review. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):752–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. de Pee S, Grede N, Mehra D, Bloem MW. The enabling effect of food assistance in improving adherence and/or treatment completion for antiretroviral therapy and tuberculosis treatment: a literature review. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maulsby C, Enobun B, Batey D, et al. A mixed-methods exploration of the needs of people living with HIV (PLWH) enrolled in access to care, a national HIV linkage, retention and re-engagement in medical care program. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(3):819–828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dowshen N, D’Angelo L. Health care transition for youth living with HIV/AIDS. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gray KM, Wang X, Li J, Nesheim SR. Characteristics and care outcomes among persons living with perinatally acquired HIV infection in the United States, 2015. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;82(1):17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Landovitz RJ, Desmond KA, Gildner JL, Leibowitz AA. Quality of care for HIV/AIDS and for primary prevention by HIV specialists and nonspecialists. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2016;30(9):395–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rackal JM, Tynan AM, Handford CD, Rzeznikiewiz D, Agha A, Glazier R. Provider training and experience for people living with HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(6):CD003938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sangsari S, Milloy M, Ibrahim A, et al. Physician experience and rates of plasma HIV-1 RNA suppression among illicit drug users: an observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Flickinger TB, Saha S, Moore RD, Beach MC. Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(3):362–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Valverde E, Rodriguez A, White B, Guo Y, Waldrop-Valverde D. Understanding the association of internalized HIV stigma with retention in HIV care. J HIV AIDS. 2018;4(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mugavero MJ, Westfall AO, Zinski A, et al. Measuring retention in HIV care: the elusive gold standard. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(5):574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental_Table_1_4.19.20 for Differential Role of Psychosocial, Health Care System and Neighborhood Factors on the Retention in HIV Care of Women and Men in the Ryan White Program by Mary Jo Trepka, Diana M. Sheehan, Rahel Dawit, Tan Li, Kristopher P. Fennie, Merhawi T. Gebrezgi, Petra Brock, Mary Catherine Beach and Robert A. Ladner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)

Supplemental_Table_2_7.11.20 for Differential Role of Psychosocial, Health Care System and Neighborhood Factors on the Retention in HIV Care of Women and Men in the Ryan White Program by Mary Jo Trepka, Diana M. Sheehan, Rahel Dawit, Tan Li, Kristopher P. Fennie, Merhawi T. Gebrezgi, Petra Brock, Mary Catherine Beach and Robert A. Ladner in Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care (JIAPAC)