Abstract

Treatment with cluster of differentiation 47 (CD47) monoclonal antibody has exhibited promising antitumor effects in various preclinical cancer models. However, its role in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains unclear. In the present study, the CD47 expression level was measured in PDAC patient samples. The effects of CD47 on antigen presentation and anti-tumor immunity were evaluated using phagocytotic assays and animal models. The results indicated that CD47 was overexpressed in the tumor tissue of PDAC patients compared with that in normal adjacent tissues. In the human samples, antigen-presenting cells (macrophages and dendritic cells) in tumors with high CD47 expression demonstrated low CD80 and CD86 expression levels. In an in vitro co-culture tumor cell system, CD47 overexpression was observed to inhibit the function of phagocytic cells. Furthermore, in a PDAC mouse model, CD47 overexpression was indicated to reduce antigen-presenting cell tumor infiltration and T-cell priming in tumor-draining lymph nodes. Anti-CD47 treatment appeared to enhance the efficacy of the approved immune checkpoint blockade agent anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (anti-CTLA4) in suppressing PDAC development in a mouse model. Therefore, it was concluded that CD47 overexpression suppressed antigen presentation and T-cell priming in PDAC. Anti-CD47 treatment may enhance the efficacy of anti-CTLA4 therapy and may therefore be a potential strategy for the treatment of PDAC patients in the future.

Keywords: cluster of differentiation 47, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, antigen presentation, macrophage, dendritic cells, anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4

Introduction

Cluster of differentiation 47 (CD47), also known as integrin-associated protein, is a membrane protein of the immunoglobulin superfamily (1). CD47 negatively regulates phagocytosis by participating in integrin and cadherin signaling through interaction with thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) and signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) (1). CD47 is ubiquitously expressed in human cells and has been found to be overexpressed in numerous cancer types (2-5). CD47 overexpression on cancer cells predicts adverse prognosis of breast, gastric, ovarian and esophagus cancer (2-5). Emerging evidence has demonstrated the critical roles of phagocytosis and antigen presentation in anti-tumor immunity (4,5). In preclinical cancer models, CD47 monoclonal antibody treatment has exhibited promising antitumor effects in various types of cancer by enhancing the activity of phagocytic cells and innate antitumor immunity (4-7). However, the effects of CD47 expression on regulating antigen presentation and T-cell priming in cancer currently remain unclear.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one of the most lethal diseases, with an estimated 53,000 new cases in the United States in 2016(8). Although comprehensive treatment strategies are available, the 5-year survival rate of PDAC patients remains dismal (9). Therefore, developing new anti-PDAC targets for novel treatments represents an urgent and unmet medical need. Immune checkpoint blockades target immune checkpoints, key regulators of the immune system, to enhance the immune response, including the anti-tumor activity (10). Anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (anti-CTLA4), an example of an immune checkpoint blockades, displayed promising anti-tumor effects in various cancers, including melanoma and colon and lung cancer (11-13); however, to the best of our knowledge, their effect has not been investigated in PDAC to date (14). The effects of anti-CTLA4 treatment largely depend on the antigen-presenting cell (APC) function and T-cell priming, which is under the regulation of APCs (15). Notably, APCs express a high level of SIRPα and are, thus, influenced by tumor cell CD47 expression.

Given these previous observations, the present study aimed to investigate whether targeting CD47 is able to enhance the function of APCs and improve the efficacy of anti-CTLA4 as a treatment for PDAC in preclinical models.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

The mouse pancreatic cancer cell line Panc02 was purchased from the Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Panc02 cells were cultured using RPMI medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA), 100 U/ml of penicillin and 100 µg/ml of streptomycin at 37˚C with 5% CO2. When the cells reached 85% confluency, subculturing was performed.

To manipulate CD47 expression, wild-type Panc02 cells (CD47-WT) were transfected with CD47-short hairpin RNA (shRNA) for expression knockdown (CD47-KD group), CD47 overexpression vector (CD47-OE group) or control nonsense vector (CD47-Ctrl group). All vectors used were lentiviral vectors purchased from OriGene Technologies, Inc. On day 1, a total of 1.2x107 293 cells (cat. no. 85120602; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) were seeded in a 10-cm dish and cultured with EMEM medium (cat. no. 30-2003; American Type Tissue Collection) at 37˚C with 5% CO2. When 70% confluency was reached, the 293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (cat. no. L3000008; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) with aCD47 overexpression vector (cat. no. MR204706L1; OriGene Technologies, Inc.), CD47 shRNA (cat. no. TL501123; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) or control vector (cat. no. PS100064; OriGene Technologies, Inc.; 20 µg each) together with the packaging vector (Lenti-vpak packaging kit; cat. no. TR30037; OriGene Technologies, Inc.) in order to produce lentiviruses to infect Panc02 cells. After 48 h of transfection, the lentivirus was harvested from the supernatant (by centrifugation at 1,500 x g at 4˚C for 5 min to remove cell debris) of the 293 cell culture and used to transduce the Panc02 cells. Panc02 cells (1.0x105) were seeded in 24-well plates, and then 0.5 ml supernatant with virus (107 particles) was added to the plates to incubate for 24 h at 37˚C. Puromycin (10 µg/ml; cat. no. A1113802; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was added to the culture medium to select the transduced Panc02 cells on day 3 after lentiviral transduction. Following 4 days of selection, the expression of CD47 on the cell membrane was measured by flow cytometry in each group in order to validate the gene expression manipulation. Briefly, 1.0x105 cells were collected and washed with PBS once at room temperature and resuspended in PBS with 5% BSA. Cells were then stained with CD47 antibody (1:100; cat. no. 127507; BioLegend, Inc.) for 20 min at room temperature. Then cells were then washed with PBS and analyzed using a FACSCanto II flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson & Company) and FlowJo software (version 9; FlowJo LLC).

Patient samples

Fresh PDAC tissues and the paired adjacent normal pancreatic tissues were collected from 20 PDAC patients diagnosed at Xi'an Gaoxin Hospital between June and December 2015. These patients met the following inclusion criteria: i) The diagnosis of PDAC was confirmed by hematoxylin-eosin staining by two certificated pathologists; ii) the patient had not accepted any chemotherapy or radiotherapy previously; iii) adequate quantities of tumor tissue and paired tumor adjacent pancreatic tissues were collected; iv) the patient did not have any immune deficient or autoimmune disease; v) the patient did not have any other severe disease; vi) the patient provided informed consent to participation in the study and agreed to the collection of follow-up information. Patients were followed-up until death or for up-to 24 months. The fresh tissues were collected during surgery and immediately used for flow cytometry analysis (as described) to measure protein expression levels. The expression of CD47 was measured in tumor and tumor-adjacent normal tissues, while the expression levels of CD80 and CD86 were measured in tumor-infiltrating APCs. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi'an Gaoxin Hospital, Ganzhou, Jiangxi, China. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal representatives through visits or phone calls and written or oral consents respectively were obtained in the presence of a public notary.

Animal model

C57BL/6 mice and the Panc02 cell line were used to establish subcutaneous mouse models of PDAC. Briefly, 5-week old male mice (Beijing HFK Bioscience, Changping, Beijing, China; weight, 18-20 g) were obtained and kept in a specific-pathogen-free environment (27˚C, 45% humidity and 12 h light/dark cycle) with free access to clean water and standard food. In order to evaluate the role of CD47 in PDAC development, mice were divided into four experimental groups (n=10 per group), and 5x105 Panc02 cells with different CD47 expression levels (CD47-OE, CD47-WT, CD47-Ctrl or CD47-KD) were respectively inoculated into the flanks of the mice.

Subsequently, the effects of anti-CD47 treatment were evaluated in the CD47-WT mouse model. Briefly, treatment with anti-CD47 (5 mg/kg/week; diluted in PBS, cat. no. BE0270; Bio X Cell, West Lebanon, NH, USA) and/or anti-CTLA4 (5 mg/kg/week; diluted in PBS, cat. no. BE0131; Bio X Cell) was initiated at 1 week after tumor inoculation via intraperitoneal injection with Panc02 cells. The tumor volume was measured and calculated every week. The tumor volume was calculated based on the following formula: Volume = length x width2 x π/6. A tumor volume that was >1,500 m3 was considered as the endpoint (euthanasia took place after 2-8 weeks depending on the rate of tumor growth and the treatment used).

Phagocytic assay

Panc02 cells were digested into single cell suspensions and then labeled with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE; eBioscience; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the manufacturer's protocol. Macrophages were purified from the peritoneal cell suspension of C57BL/6 mice (the same source and breeding condition as stated in the animal odel paragraph, pooled cells from 3 mice). Briefly, 10 ml saline was injected to the peritoneal cavity and incubated for 10 min. The saline was then collected for macrophage isolation using the Macrophage Isolation kit (Peritoneum), mouse, cat. no. 130-110-434, Miltenyi Biotec GmbH) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Dendritic cells (DCs) were also isolated from a cell suspension of spleens of C57BL/6 mice (pooled samples from 3 mice) using a DC isolation kit (CD8+ Dendritic Cell Isolation kit; cat. no. 130-091-169, Miltenyi Biotec GmbH) following the manufacturer's protocol. Subsequently, CFSE-labeled Panc02 cells (105) were co-cultured with the C57BL/6 mouse macrophages (0.2x105) or DCs (0.2x105) for 2 h. The phagocytic index was calculated by dividing the number of CFSE-positive macrophages or DCs by the total number of macrophages or DCs. To study the effects of CD47 on phagocytosis, tumor cells were treated with anti-CD47 antibodies. For anti-CD47 treatment, Panc02 cells were exposed to 20 µg/ml purified anti-mouse CD47 antibody (cat. no. BE0270; Bio X Cell) for 30 min at room temperature. The control group cells were exposed to the same dose of isotype IgG (cat. no. BE0089; Bio X Cell).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis

Single cell suspensions were generated by dissociating the fresh human and mouse tissue samples (including normal pancreas and pancreatic cancers) using collagenase IV (5 mg/ml; cat. no. 17104019; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and deoxyribonuclease (DNase I; 50 units/ml; cat. no. EN0525; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C for 1 h. Cultured cell lines were collected by trypsinization (0.05% for 5 min at 37˚C). Next, cells were incubated with fluorochrome-conjugated primary antibodies on ice for 30 min, followed by thoroughly washing with PBS. The cells were then analyzed with the FACSCanto II device (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and the results were read on the FlowJo software (FlowJo LLC, Ashland, OR, USA). All the primary antibodies used in the flow cytometry analyses were purchased from BioLegend, Inc. (San Diego, CA, USA), and are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Antibodies used in the flow cytometry experiments of the present study.

| A, Antibodies used for flow cytometry in murine samples | |

|---|---|

| Protein antibody raised against | Catalog number |

| CD11c | 117307 |

| F4/80 | 123133 |

| MHC-II | 107651 |

| CD11b | 101220 |

| CD68 | 137017 |

| CD80 | 104715 |

| CD86 | 105035 |

| CD8 | 100747 |

| CD3 | 100225 |

| CD4 | 116011 |

| B, Antibodies used for flow cytometry in human samples | |

| Protein antibody raised against | Catalog number |

| CD11c | 301634 |

| MHC-II | 307625 |

| CD11b | 301323 |

| CD68 | 333819 |

| CD80 | 305213 |

| CD86 | 341407 |

| CD47 | 323108 |

All antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:100 and were supplied by BioLegend, Inc.

In mouse samples, the CD11c+MHC-II+ and CD11b+F4/80+ markers were used for gating DCs and macrophages, respectively. gp70 protein is known to be widely expressed by mouse tumor cell lines, but not by normal tumor tissue (16). Thus, gp70 tetramers (peptide, VGRVPIGPNP; QuickSwitch™ Custom Tetramer kit; cat. no. TB-7400-K2; MBL International Corporation, Woburn, MA, USA) were used to detect gp70+ CD8 T-cell, and these were considered as tumor-specific T-cells. In human samples, the markers CD11c+MHC-II+ and CD11b+CD68+ were used for gating of DCs and macrophages, respectively. Data were visualized by FlowJo software (version 9), and the mean fluorescence intensity was used for statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS (version 17.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism software (version 7; GraphPad Software, Inc.). The differences between the mean values were accordingly analyzed using t-test or one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Survival analysis was performed by the Kaplan-Meier method. The difference between survival curves was assessed by the log-rank test. Quantified data presented in the bar plots are shown as the mean ± standard deviation. A two-tailed P-value of <0.05 was considered to denote a statistically significant difference.

Results

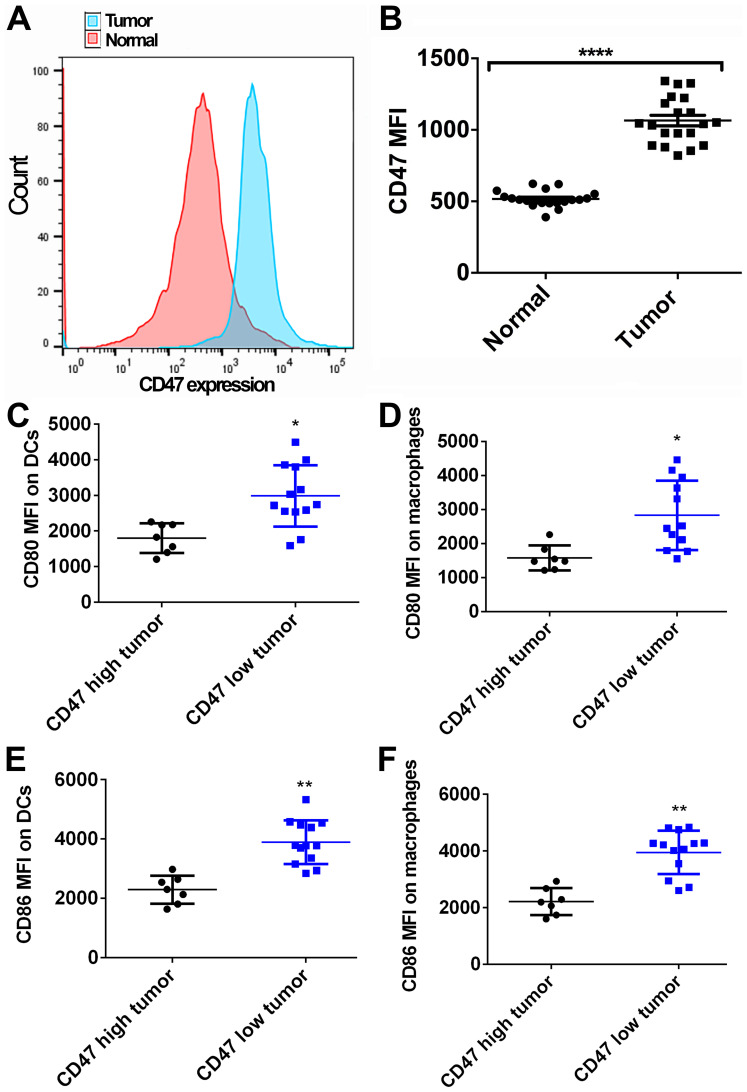

CD47 is overexpressed in PDAC samples and is associated with decreased APC activation

To reveal the role of CD47 in PDAC development, the CD47 expression levels in PDAC tissues were first evaluated. The clinicopathological features of the patients included in the present study are summarized in Table II. The average age of these patients was 61.5±5.8 years. In total, 12 patients were male and 8 were female. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, 20 normal fresh pancreatic tissue samples and the paired PDAC tissue samples were collected and analyzed by FACS. The CD47 expression on tumor cells was found to be higher in the PDAC tissue as compared with that on ductal cells in the adjacent normal pancreatic tissue (P<0.0001). Furthermore, the effects of CD47 expression on DC and macrophages' activation were evaluated. Tumor samples exhibiting higher CD47 expression level than the mean value were considered as the CD47 high expression tumors. A total of 7 out of 20 cases were classified as high CD47 expression tumors, while the remaining 13 cases were considered as CD47 low expression tumors. Significantly higher levels of CD80 and CD86 were detected in DCs and macrophages identified in CD47 low expression tumors by FACS, in comparison to the CD47 high expression tumors (MFI: Mean fluorescent intensity; unpaired t-test was used to compare the CD80/CD86 MFI between indicated groups; Fig. 1C-F). Therefore, it is suggested that CD47 may serve an important role in promoting PDAC development via suppressing the function of APCs.

Table II.

Clinicopathological features of the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients.

| Feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 61.5±5.8a |

| Gender (male/female) | 12/8 |

| Tumor stage (T2/T3) | 9/11 |

| Lymph node metastasis (no/yes) | 14/6 |

| Distant metastasis (no/yes) | 17/3 |

| Survival, months | 37.6±9.3a |

| Follow-up outcome (alive/dead) | 4/16 |

aPresented as the mean ± standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Expression of CD47 and activation of antigen-presenting cells in PDAC samples. (A) CD47 expression in normal pancreatic and paired tumor tissues was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (sample size=20). Tumor tissues exhibited higher CD47 expression as compared with that in normal tissues. (B) Quantified data showing that the MFI of CD47 in tumor tissues was higher than that in normal tissues. (C) DCs and (D) macrophages exhibited higher CD80 expression in human PDAC samples with low CD47 expression. (E) DCs and (F) macrophages exhibited higher CD86 expression in human PDAC samples with low CD47 expression. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ****P<0.0001. CD47, cluster of differentiation 47; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; DCs, dendritic cells.

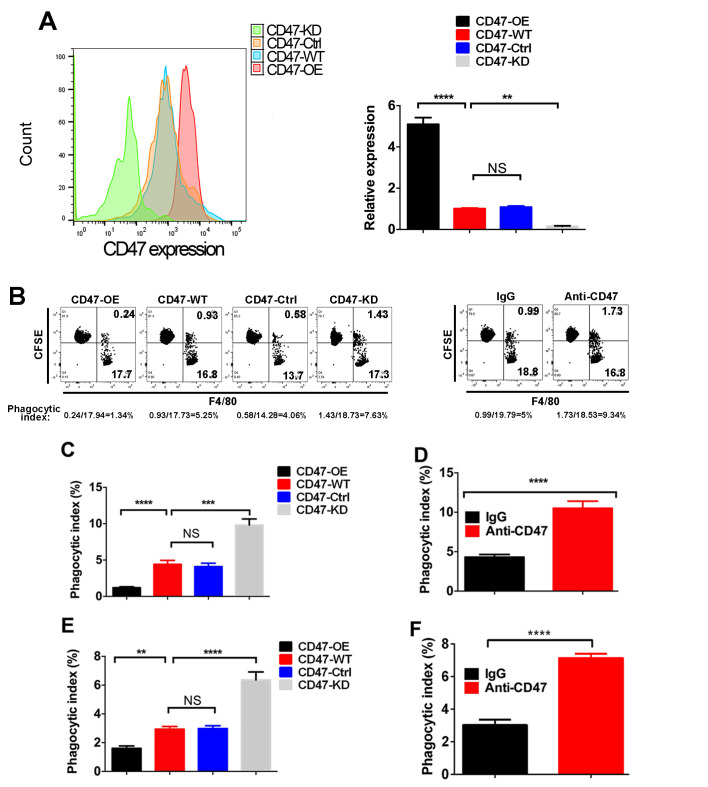

CD47 overexpression in PDAC cells inhibits the phagocytosis of APCs in vitro

To further explore the role of CD47 in PDAC, different CD47 expression levels were induced in the PDAC cell line Panc02, resulting in CD47-OE, CD47-KD, CD47-WT and CD47-Ctrl cells (Fig. 2A). Next, the phagocytosis index of these cells was measured in the macrophage-Panc02 co-culture system via FACS method (Fig. 2B). As shown in Fig. 2C, the phagocytosis index of CD47-OE Panc02 cells was decreased compared with that in the CD47-WT Panc02 cells and CD47-Ctrl Panc02 cells, while the phagocytosis index of the CD47-KD Panc02 cells was highly increased. When CD47 was blocked by the anti-CD47 antibody, the phagocytic function of macrophages was rescued (Fig. 2D). Similar results were observed in DCs (Fig. 2E and F).

Figure 2.

Effects of increased CD47 expression on phagocytosis of macrophages and DCs. (A) FACS analysis confirmed the CD47 expression manipulation in Panc02 cells (B) Representative dot plots indicating how the phagocytic index was measured by FACS method (Q3 indicates the Panc02 cells that were phagocytosed by macrophages). (C) Panc02 cells with various expression levels of CD47 were co-cultured with macrophages, and the phagocytic index was measured. Quantified data revealed that macrophages had a higher phagocytic index in CD47-KD Panc02 cells. (D) Anti-CD47 treatment significantly rescued the phagocytic function of macrophages. (E) CD47-overexpressing tumor cells inhibited the phagocytic function of DCs. (F) Anti-CD47 treatment significantly rescued the phagocytic function of DCs. All the experiments were repeated three times.**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 ****P<0.0001. CD47, cluster of differentiation 47; OE, overexpression; WT, wide type; Ctrl, control; KD, knockdown; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

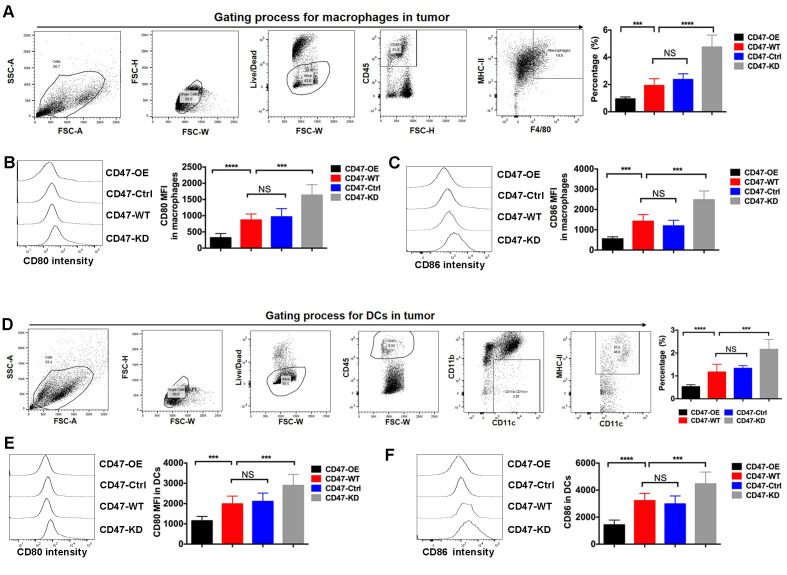

CD47 overexpression inhibits APC infiltration and functions in the PDAC mouse model

A PDAC syngeneic mouse model was further established using Panc02 cell lines with various CD47 expression levels. Through the FACS method, the ratio of two key APCs, namely macrophages and DCs, was measured in tumor tissues. The results indicated that the percentages of macrophages and DCs in CD47-OE tumors were significantly decreased, while these were markedly increased in the CD47-KD tumors (Fig. 3A and D). CD80 and CD86 are the two key ligands of CD28 and CTLA4, respectively, which are critical in modulating T-cell priming. It was further observed that the expression levels of CD80 and CD86 were reduced in macrophages of CD47-OE tumors (Fig. 3B and C). Similarly, the expression levels of CD80 and CD86 in DCs isolated from the CD47-OE tumors were decreased (Fig. 3E and F).

Figure 3.

CD47 overexpression inhibited antigen-presenting cell infiltration and activity in a pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma mouse model. The mouse model was established using Panc02 cell lines with various CD47 expression levels, and the ratio of macrophages and DCs was measured by the fluorescence-activated cell sorting method. (A) The representative flow plots showed gating of macrophages in tumors. The CD47-OE tumor tissues exhibited the lowest percentage of macrophages. (B) CD80 and (C) CD86 expressed in macrophages isolated from CD47-OE tumor tissues were the lowest compared with other groups. Representative histograms of signal intensity were shown for each group. (D) The representative flow plots showed gating of DCs in tumors. The CD47-OE tumor tissues exhibited the lowest percentage of DCs. (E) CD80 and (F) CD86 expression levels were significantly reduced in the DCs isolated from CD47-OE tumor tissues. Representative histograms of signal intensity were shown for each group. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. CD47, cluster of differentiation 47; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity; OE, overexpression; WT, wide type; Ctrl, control; KD, knockdown.

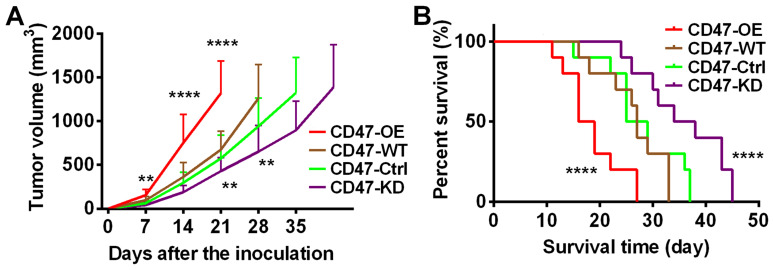

The study also investigated the effects of CD47 expression on tumor development. As shown in Fig. 4A, it was observed that PDAC tumors with CD47 overexpression grew at a much faster rate compared with tumors with lower CD47 expression. Consistently, the survival time of the mice with CD47-OE tumors was the shortest among all groups (Fig. 4B). Taken together, this evidence indicated that CD47 suppressed the infiltration and functions of the macrophages and DCs in PDAC tumors. These data were in line with our findings in human samples.

Figure 4.

Effects of CD47 overexpression on PDAC development. A PDAC syngeneic mouse model was established using Panc02 cell lines with various CD47 expression levels. (A) Growth of tumors established by CD47-OE cells was the fastest as compared with the other groups. (B) Mice with CD47-OE tumors had the lowest survival rate as compared with the other groups (n=10 in each group). **P<0.01, ****P<0.0001 vs. CD47-WT. CD47, cluster of differentiation 47; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; OE, overexpression; WT, wide type; Ctrl, control; KD, knockdown.

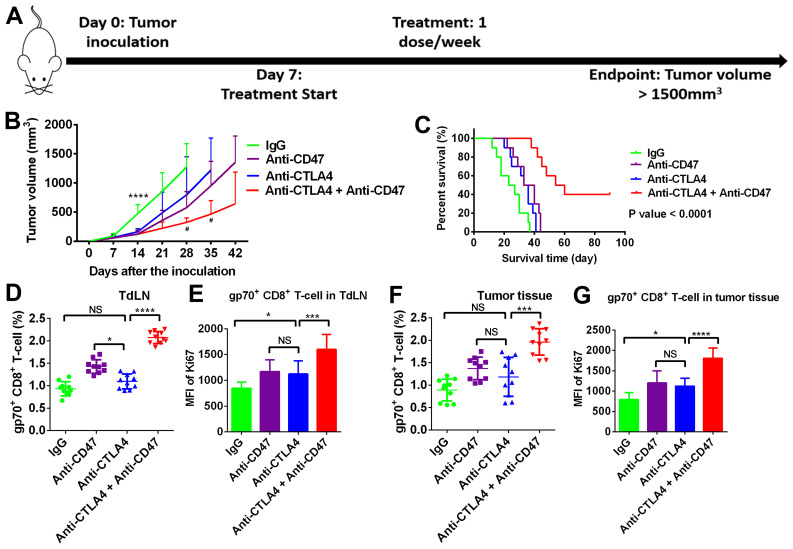

Anti-CD47 treatment enhances the efficacy of anti-CTLA4 treatment in suppressing PDAC development

Since anti-CD47 increased phagocytic function and B7 molecule (CD80 and CD86) expression in APCs, the current study further investigated whether anti-CD47 is able to enhance anti-CTLA4 efficacy in T-cell priming and suppress PDAC development (Fig. 5A). In the PDAC subcutaneous mouse model, the tumors co-treated with anti-CD47 and anti-CTLA4 antibodies grew much slower when compared with the untreated and monotherapy-treated tumors (Fig. 5B). The survival time of the mice co-treated with anti-CD47 and anti-CTLA4 antibodies was evidently extended (log-rank test P-value of <0.01; Fig. 5C). The present study further investigated T-cell priming in the tumor-draining lymph node (TdLN) and T-cell infiltrating in tumor tissues. As shown in Fig. 5D and E, the numbers and proliferation rate of tumor-specific CD8 T-cells (gp70+) in TdLN were significantly increased by the anti-CD47 and anti-CTLA4 combination treatment. Similar results were observed in tumor tissues (Fig. 5F and G).

Figure 5.

Anti-CD47 treatment enhanced the efficacy of anti-CTLA4 treatment via stimulating anti-tumor immunity. (A) The experimental scheme. (B) Growth of tumors co-treated with anti-CD47 and anti-CTLA4 antibodies was slower in comparison with tumors treated with monotherapy. ****P<0.0001 vs. IgG group; #P<0.05 vs. anti-CTLA4 group) (C) Mice co-treated with anti-CD47 and anti-CTLA4 antibodies exhibited longer survival as compared with mice receiving monotherapy. (D) Number of gp70+ CD8 T-cells and (E) Ki-67 expression in the tumor-draining lymph node were increased by anti-CD47 and anti-CTLA4 combination treatment. (F) Number of gp70+ CD8 T-cells and (G) Ki-67 expression levels in tumor tissues were higher in the anti-CD47 and anti-CTLA4 combination treatment group. Sample size=10 per group. *P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and ****P<0.0001. CTLA4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4. CD47, cluster of differentiation 47; MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Discussion

CD47 is a membrane protein of the immunoglobulin superfamily that is widely expressed on human cells and overexpressed in certain types of cancer (1). CD47 negatively regulates phagocytosis of macrophages and DCs by interacting with TSP-1 and SIRPα (1). Previous studies have demonstrated that CD47 overexpression promoted tumor development via suppressing the phagocytic function of macrophages and innate antitumor immunity. However, the role of CD47 in regulating antigen presentation in PDAC and the value of targeting CD47 in treating PDAC have yet to be determined.

The expression and prognostic value of CD47 have been studied in multiple types of cancer, including breast, gastric, ovarian and esophagus cancer (2-5). In line with these previous studies, the results of the present study revealed that CD47 expression was upregulated in PDAC tumors by comparing PDAC tissues with tumor-adjacent normal tissues. In addition, the B7 molecule expression on APCs was compared in human tumors exhibiting high and low CD47 expression. Notably, the B7 molecules showed higher expression in APCs isolated from CD47 low expression tumors. These data suggested that CD47 exerted tumor promoting effects in PDAC and provided the rationale for investigating its roles in regulating antigen presentation.

Phagocytic cells, such as DCs and macrophages, have profound antitumor activity via killing tumor cells by secreting cytokines and functioning as APCs to stimulate adaptive immunity (17,18). Phagocytosis mainly depends on macrophage/DC recognition of pro-phagocytic molecules on target cells, however it can be inhibited by simultaneous expression of anti-phagocytic molecules, such as CD47(19). In line with previous studies, the current study revealed that overexpression of CD47 in PDAC cells significantly reduced the phagocytic activity of macrophages and DCs in vitro. Furthermore, in the syngeneic PDAC mouse model, overexpression of CD47 facilitated tumor growth, but reduced tumor tissue infiltration of macrophages and DCs. The activation of tumor infiltrating macrophages and DCs was further examined, which was also found to be suppressed by CD47-overexpressing PDAC cells.

In the PDAC mouse model of the current study, blocking CD47 reduced tumor development and prolonged animal survival. In a previous esophagus cancer model, blocking CD47 significantly restored T-cell activation and delayed tumor development (5). Similar antitumor effects of anti-CD47 treatment were also observed in ovarian cancer and glioma (4,20). More notably, the present study results indicated that blocking CD47 in tumor cells has demonstrated positive effects in sensitizing PDAC to the currently used immune checkpoint blockade agent anti-CTLA4 through the mechanisms of enhancing antigen presentation. These observations were in line with the findings of a recent study in an esophageal cancer model (5). It is known that impaired antigen presentation, which relies on the function of phagocytic cells, is one major reason for resistance to immune checkpoint blockades (21-23). PDAC is considered as a poor immune infiltrated cancer that is highly resistant to immunotherapies (24,25). Thus, the data of the present study implied the potential of combining anti-CD47 treatment with the existing immune checkpoint blockades in future clinical trials. The effect of anti-CD47 treatment in PDAC has also been highlighted in the study by Cioffi and colleagues (26). It was reported that anti-CD47 treatment alone did not result in direct inhibition of tumor growth. However, when combined with chemotherapy, anti-CD47 treatment achieved sustained tumor regression in patient-derived xenograft models (26). Another study reported that anti-CD47 treatment increased the clearance of PDAC cells by macrophages (27). In line with these previous findings, the present study highlighted the therapeutic value of anti-CD47 on PDAC when combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that CD47 is overexpressed in PDAC tissues, while overexpression of CD47 accelerated PDAC development by inhibiting the function of APCs. Blocking the CD47 function using monoclonal antibody treatment ehanced the efficacy of anti-CLTA4 treatment in suppressing preclinical PDAC development. Therefore, combining anti-CD47 treatment with current standard immune checkpoint therapies may be of great value against PDAC in future studies.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was funded by Xi'an Gaoxin Hospital.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

XS and ZL analyzed and interpreted the patient data and performed the in vitro and in vivo experiments. JX analyzed the experimental data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi'an Gaoxin Hospital, Ganzhou, Jiangxi, China. Informed consent was obtained from all patients or their legal representatives.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Matozaki T, Murata Y, Okazawa H, Ohnishi H. Functions and molecular mechanisms of the CD47-SIRPalpha signalling pathway. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baccelli I, Stenzinger A, Vogel V, Pfitzner BM, Klein C, Wallwiener M, Scharpff M, Saini M, Holland-Letz T, Sinn HP, et al. Co-expression of MET and CD47 is a novel prognosticator for survival of luminal breast cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2014;5:8147–8160. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida K, Tsujimoto H, Matsumura K, Kinoshita M, Takahata R, Matsumoto Y, Hiraki S, Ono S, Seki S, Yamamoto J, Hase K. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and a therapeutic target in gastric cancer. Cancer Med. 2015;4:1322–1333. doi: 10.1002/cam4.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu R, Wei H, Gao P, Yu H, Wang K, Fu Z, Ju B, Zhao M, Dong S, Li Z, et al. CD47 promotes ovarian cancer progression by inhibiting macrophage phagocytosis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:39021–39032. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao H, Qian P, Wang F, Yu H, Guo Y. Targeting CD47 enhances the efficacy of anti-PD-1 and CTLA-4 in an esophageal squamous cell cancer preclinical model. Oncol Res. 2017;25:1579–1587. doi: 10.3727/096504017X14900505020895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, Zhang L, Yang L, Li H, Li R, Yu J, Yang L, Wei F, Yan C, Sun Q, et al. Anti-CD47 antibody as a targeted therapeutic agent for human lung cancer and cancer stem cells. Front Immunol. 2017;8(404) doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Fan J, Wang S, Li Y, Wang Y, Li S, Luan J, Wang Z, Song P, Chen Q, et al. Targeting CD47 and autophagy elicited enhanced antitumor effects in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2017;5:363–375. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulson AS, Cao HS, Tempero MA, Lowy AM. Therapeutic advances in pancreatic cancer. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1316–1326. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Topalian SL, Drake CG, Pardoll DM. Immune checkpoint blockade: A common denominator approach to cancer therapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:450–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber J, Mandala M, Vecchio MD, Gogas HJ, Arance AM, Cowey CL, Dalle S, Schenker M, Chiarion-Sileni V, Marquez-Rodas I, et al. Adjuvant nivolumab versus ipilimumab in resected stage III or IV melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1824–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reck M, Schenker M, Lee KH, Provencio M, Nishio M, Lesniewski-Kmak K, Sangha R, Ahmed S, Raimbourg J, Feeney K, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer with high tumour mutational burden: Patient-reported outcomes results from the randomised, open-label, phase III CheckMate 227 trial. Eur J Cancer. 2019;116:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winer A, Ghatalia P, Bubes N, Anari F, Varshavsky A, Kasireddy V, Liu Y, El-Deiry WS. Dual checkpoint inhibition with ipilimumab plus nivolumab after progression on sequential PD-1/PDL-1 inhibitors pembrolizumab and atezolizumab in a patient with lynch syndrome, metastatic colon, and localized urothelial cancer. Oncologist. 2019;24:1416–1419. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symeonides SN, Anderton SM, Serrels A. FAK-inhibition opens the door to checkpoint immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5(17) doi: 10.1186/s40425-017-0217-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu FJ, Komarovskaya M. CTLA4 blockade maximizes antitumor T-cell activation by dendritic cells presenting idiotype protein or opsonized anti-CD20 antibody-coated lymphoma cells. J Immunother. 2002;25:455–468. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200211000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scrimieri F, Askew D, Corn DJ, Eid S, Bobanga ID, Bjelac JA, Tsao ML, Allen F, Othman YS, Wang SC, Huang AY. Murine leukemia virus envelope gp70 is a shared biomarker for the high-sensitivity quantification of murine tumor burden. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(e26889) doi: 10.4161/onci.26889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klimp AH, de Vries EGE, Scherphof GL, Daemen T. A potential role of macrophage activation in the treatment of cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2002;44:143–161. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palucka K, Banchereau J. Cancer immunotherapy via dendritic cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:265–277. doi: 10.1038/nrc3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordon S. Phagocytosis: An immunobiologic process. Immunity. 2016;44:463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gholamin S, Mitra SS, Feroze AH, Liu J, Kahn SA, Zhang M, Esparza R, Richard C, Ramaswamy V, Remke M, et al. Disrupting the CD47-SIRPalpha anti-phagocytic axis by a humanized anti-CD47 antibody is an efficacious treatment for malignant pediatric brain tumors. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(eaaf2968) doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Subramanian S. Intrinsic resistance of solid tumors to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Res. 2017;77:817–822. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitt JM, Vétizou M, Daillère R, Roberti MP, Yamazaki T, Routy B, Lepage P, Boneca IG, Chamaillard M, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Resistance mechanisms to immune-checkpoint blockade in cancer: Tumor-intrinsic and -extrinsic factors. Immunity. 2016;44:1255–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sindoni A, Minutoli F, Ascenti G, Pergolizzi S. Combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors and radiotherapy: Review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2017;113:63–70. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mace TA, Shakya R, Pitarresi JR, Swanson B, McQuinn CW, Loftus S, Nordquist E, Cruz-Monserrate Z, Yu L, Young G, et al. IL-6 and PD-L1 antibody blockade combination therapy reduces tumour progression in murine models of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2018;67:320–332. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ino Y, Yamazaki-Itoh R, Shimada K, Iwasaki M, Kosuge T, Kanai Y, Hiraoka N. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:914–923. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cioffi M, Trabulo S, Hidalgo M, Costello E, Greenhalf W, Erkan M, Kleeff J, Sainz B Jr, Heeschen C. Inhibition of CD47 effectively targets pancreatic cancer stem cells via dual mechanisms. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2325–2337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michaels AD, Newhook TE, Adair SJ, Morioka S, Goudreau BJ, Nagdas S, Mullen MG, Persily JB, Bullock TNJ, Slingluff CL Jr, et al. CD47 blockade as an adjuvant immunotherapy for resectable pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24:1415–1425. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.