Highlights

-

•

Incidence of mental disorders is relatively low under the long-term of COVID-19.

-

•

The real-time news trends affect the psychological state of the public.

-

•

Public's poor mental state will be alleviated while controlling the pandemic.

Keywords: COVID-19, Mental health, Geographical distribution, Temporal distribution, General public

Abstract

Background

The mental health status caused by major epidemics is serious and lasting. At present, there are few studies about the lasting mental health effects of COVID-19 outbreak. The purpose of this study was to investigate the mental health of the Chinese public during the long-term COVID-19 outbreak.

Methods

A total of 1172 online questionnaires were collected, covering demographical information and 8 common psychological states: depression, anxiety, somatization, stress, psychological resilience, suicidal ideation and behavior, insomnia, and stress disorder. In addition, the geographical and temporal distributions of different mental states were plotted.

Results

Overall, 30.1% of smokers increased smoking, while 11.3% of drinkers increased alcohol consumption. The prevalence rates of depression, anxiety, mental health problems, high risk of suicidal and behavior, clinical insomnia, clinical post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, moderate-to-high levels of perceived stress were 18.8%, 13.3%, 7.6%, 2.8%, 7.2%, 7.0%, and 67.9%, respectively. Further, the geographical distribution showed that the mental status in some provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities was relatively more serious. The temporal distribution showed that the psychological state of the participants was relatively poorer on February 20, 24 to 26 and March 25, especially on March 25.

Limitations

This cross-sectional design cannot make causal inferences. The snowball sampling was not representative enough.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that the prevalence rate of mental disorders in the Chinese public is relatively low in the second month of the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, people's mental state is affected by the geographical and temporal distributions.

- COVID-19

2019 coronavirus disease

- (WHO)

World Health Organization

- PHQ-9

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

- DSM

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

- GAD-7

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7

- SCL-90

Symptom Check List 90

- SOM

somatization of Symptom Check List 90

- PSS-10

Perceived Stress-10 Scale

- CD-RISC-10

10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale

- MINI

Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview

- ISI

Insomnia Severity Index

- ASDS

Acute Stress Disorder Scale

- PCL-5

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5

- PTSD

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

- IQR

Interquartile range

- BMI

Body Mass Index.

1. Introduction

The 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been characterized as a pandemic by World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11, 2020 because of its strong infectivity, high incidence and great health hazards. It has been raging in China since January 10, 2020. Although it was basically under control in China, it has spread rapidly around the world at present. As of May 17, a total of 4.52 million people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, with 307,395 deaths (WHO, 2020), and the case fatality rate was as high as 6.8%. It is the focus of global attention recently. In Wuhan, China, where the infectious disease was first reported, in order to cut off the route of transmission, the government adopted lockdown measures on January 23, 2020. Other places have restricted mobility and travel one after another, and 1.4 billion people across the country have been banned, except for special posts. Almost all of Chinese had to stay at home, which has affected every aspect of life. As a public health emergency, mental health problems of COVID-19 pandemic cannot be ignored. The incidence of poor mental health of the public is very high (Cullen et al., 2020; Page et al., 2011), which has brought a lot of negative effects to themselves, family members, relatives and friends, society, and even the country (Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020). In addition, studies have shown that psychological factors play an important role in public compliance with public health measures and in dealing with the threat of infection and related losses (Taylor, 2019).

In China, Professor Xiang firstly proposed that the mental and psychological intervention caused by COVID-19 was imminent (Li et al., 2020). Then, a recent investigation of psychological distress among the Chinese public reported that nearly 35% of the 52,730 participants experienced psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic, surveyed by psychiatrists at Shanghai Mental Health Center (Qiu et al., 2020). Another study reported that 2 weeks after the outbreak of COVID-19 in China, more than half of the subjects thought that the degree of psychological influence was moderate to severe, while about 1/3 of the subjects had moderate to severe anxiety (Wang et al., 2020a). Internationally, there are also many reports on people's mental health during the H1NA pandemic. For example, Goodwin et al. reported the regional differences in anxiety indicators between Malaysians and Europeans within 6 days after WHO was on alert level 5 for H1N1 pandemic, showing that Malaysians were more anxious than Europeans (Goodwin et al., 2009). Lau et al. reported the negative psychological reactions of ordinary people in the early days of the H1N1 pandemic in Hong Kong, showing that 15% of people were very worried about H1N1 infection and 6% had signs of emotional distress (Lau et al., 2010).

The COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented in history and has a great impact. Only a few studies have been conducted to investigate the mental health problems of the public during the COVID-19 pandemic, with comparatively few contents of relevant mental health issue. Moreover, the investigation only focused on the psychological status in the early stages of the outbreak. The long-term psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have not been tracked. A previous study showed that the psychological effects of an infectious disease lasted up to 4 months or more (Peng et al., 2010).

The purpose of this study was to investigate mental health status of the public during the long-term effects of COVID-19 in China. This pandemic is unprecedentedly large, with a long incubation period, during which COVID-19 is also contagious (Sanche et al., 2020). It is now raging all over the world, and the pandemic is still in development. We hope that our research on the psychological status of the public can provide a reference for other regions to reduce the occurrence of adverse psychological status of the public.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants and data collection

A cross-sectional study was performed from February 14 to March 29, 2020. In the study, snowball sampling method was used to recruit Chinese residents who could operate mobile phones. Participants scanned and identified the Wechat QR code on their mobile phones to fill in the questionnaire established by an online survey platform, Ranxing Technology "SurveyStar" based in Changsha, Shanghai, China. Each questionnaire can only be conducted with the consent of the participants. They can opt out at any time without saving the data, and they will not receive any financial reward for filling out the questionnaire. The Ethics Committee for Scientific Research, Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences approved the study. Finally, a total of 1172 participants from 133 cities were recruited.

We chose China for two reasons. First, the main purpose of our study was the long-term impact of COVID-19 pandemic on public mental health in the context of Chinese culture. Second, the Chinese public experienced the COVID-19 pandemic earlier than other countries, and the impact of the pandemic on the Chinese public was longer than that of other countries.

2.2. Measures

The questionnaire used in this survey was a structured self-rating questionnaire, which included the following 9 aspects.

Demographic characteristics—We collected the demographic information of the subjects, including sex, age, height, weight, nationality, marriage, education level, place of residence, employment status, annual household income, history of somatic diseases, COVID-19 infection in relatives and friends, history of SARS epidemic in 2003, economic losses caused by COVID-19, smoking and drinking habits.

Psychological depression—Psychological depression was rated by the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which is widely used to assess the depression levels in general population (Maske et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2012). PHQ-9 asks subjects to assess how often they experienced depressive symptoms in the previous two weeks: 0–3 (not at all to almost every day). PHQ-9 was complied according to the diagnostic criteria of depression in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)−4, including 9 items (Guo et al., 2017). The total score of these 9 item was used to reflect the severity of depression, ranging from 0 to 27. A score of 10 or higher indicates the current depressive symptoms (Kroenke et al., 2001).

Psychological anxiety—Psychological anxiety was screened by the Chinese version Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 (GAD-7), and its 7 items correspond to the diagnostic criteria of generalized anxiety disorder in the DSM-4 (Hughes et al., 2018). Each item is rated from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day), based on how often the respondent has experienced symptoms in the past two weeks, with the total score ranging from 0 to 21. A higher score indicates more severe symptoms of anxiety. The cut-off value of 8 points represents obvious clinical anxiety symptoms in general population (Hughes et al., 2018).

Somatization—Somatization was assessed by the first subscale of Chinese version Symptom Check List 90 (SCL-90) (Fau et al., 1973), named somatization (SOM), which includes 12 items. SCL-90 is widely used in the Chinese general population (Yu et al., 2019), and it is measured with a 5-point Likert scale. Item 1 (no) to item 5 (severe) represent the severity of the symptoms. Therefore, the higher the score, the higher the frequency and intensity of symptoms, with a total score ranging from 12 to 60 points. A score ≥ 24 indicates potential mental health problems (Li et al., 2018).

Psychological stress—Psychological stress was measured by the Chinese version Perceived Stress-10 Scale (PSS-10), including 6 negative and 4 positive items. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) (Huang et al., 2020). Therefore, the score of PSS-10 ranges from 0 to 40. The higher the total score, the higher the psychological stress. A score≥14 indicates that the perceived stress is at a moderate to high level (Wiriyakijja et al., 2020).

Psychological Resilience—Psychological resilience was assessed by the simplified Chinese version of 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10), which is widely used in different populations (Cheng et al., 2020). Each item ranges from 0 (not true at all) to 4 (true almost all of the time). A high total score reflects a great ability to cope with adversity (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007), ranging from 0 to 40 points.

Suicidal ideation and behaviors—Suicide risk was rated by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) suicidality module (Sheehan et al., 1998), which includes 6 questions about suicidal ideation and behavior. The total score divides the current suicide risk into three levels: a score between 1 and 5 is considered low risk, a score between 6 and 9 is considered moderate risk, and a score above 10 is considered high risk (Lim et al., 2014).

Insomnia—Insomnia was measured using the Chinese version of the 7-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) (Morin, 1996), which has been widely used by many researchers over the past 30 years. The scale is of the Likert-type with 5 anchor points, ranging from 0 to 4. Therefore, the total score ranges from 0 to 28. A higher total score indicates the more serious insomnia. A cut-off value of 15 has been used as threshold for a clinically relevant insomnia (Castronovo et al., 2016). The scale is based on the evaluation of the situation in the last 2 weeks (Chung et al., 2011).

Stress disorder—Stress disorder was screened by two Chinese version scales. We originally designed the Acute stress disorder scale (ASDS). With the extension of the time span of the survey, the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) was more suitable, so we replaced ASDS with PCL-5. Finally, we collected 714 questionnaires using the ASDS, and the remaining 458 questionnaires using the PCL-5. The ASDS has 7 items. The scale anchor is 0–4, and the total score is 0–28. The higher the total score, the more serious the symptoms of acute stress disorder. PCL-5 includes 20 items, with scale anchor of 0–4 (Weathers et al., 2013). Thus, the total score ranges from 0 to 80. The higher the total score, the more serious the symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). A score more than the cut-off score of 33 on PCL-5 is defined as stress disorder (Krüger-Gottschalk et al., 2017).

2.3. Statistical analyses

We conducted a descriptive statistical analysis of the demographic characteristics and other selected characteristics of the respondents. In order to test the internal consistency, reliability test was used to analyze the PHQ-9, GAD-7, SOM of SCL-90, PSS-10, CD-RISC-10, MINI suicidality module, ISI, and ASDS/PCL-5, respectively. Data were depicted using SPSS version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The geographical and temporal distributions of different mental states were plotted using Tableau Desktop version 10.4 (Tableau Software, Inc., Washington, USA) and Microsoft Office Excel 2007, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Development of the COVID-19 pandemic from January 10 to March 29 2020

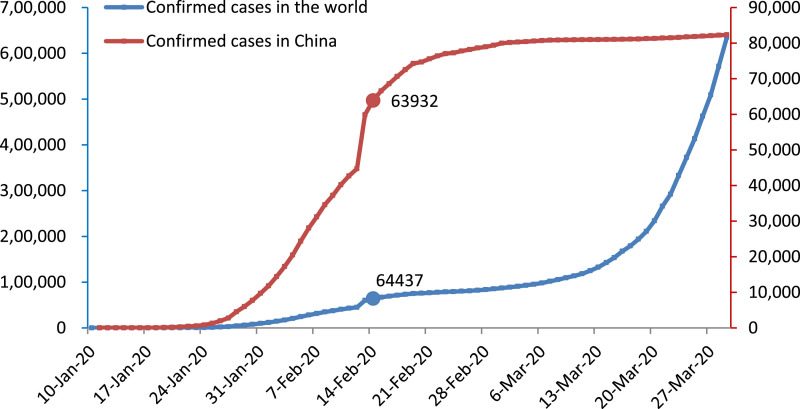

Fig. 1 shows the development trend of the COVID-19 pandemic in China and around the world from January to March 2020, respectively. The data after February 14 was at the stage when the curve of confirmed COVID-19 cases in China was relatively flat, while the global pandemic situation was in the stage of slow growth to sharp growth during this period.

Fig. 1.

Pandemic situation in China and the world.

3.2. Survey respondents

The demographic characteristics and selected characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1 . Their ages ranged from 13 to 70 years, with a median age of 22.0 (Interquartile range, IQR, 21.0–37.0) years. The majority of the participants (69.3%) were female. The median height, weight, and Body Mass Index (BMI) were 165.0 cm, 60.0 kg, and 21.5 kg/m2, respectively. The majority (69.1%) were unmarried. Few participants (2.1%) had education level of junior high school or below. Nearly half of the participants (50.1%) were full-time students. Most of the participants’ annual household income (89.3%) was less than 42,962 dollars.

Table 1.

Participants’ demographic characteristics.

| Variable | N (%) / Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 360 (30.7%) |

| Female | 812 (69.3%) |

| Age | 22.0 (21.0–37.0) |

| Height (cm) | 165.0 (160.0–171.0) |

| Weight (kg) | 60.0 (53.5–67.0) |

| BMI | 21.5 (19.7–24.2) |

| Nationality | |

| Han | 1113 (95.0%) |

| Others | 59 (5.0%) |

| Marriage | |

| Unmarried | 810 (69.1%) |

| Married | 461 (39.3%) |

| Education level | |

| Undergraduate or above | 782 (66.7%) |

| Junior college | 223 (19.1%) |

| Senior high school | 142 (12.1%) |

| Junior high school or below | 25 (2.1%) |

| Occupation | |

| Full-time students | 587 (50.1%) |

| Already working | 585 (49.9%) |

| Annual household income (US dollars) | |

| More than 143,207 | 11 (0.9%) |

| 42,962 to 143,207 | 115 (9.8%) |

| 11,457 to 42,962 | 546 (46.6%) |

| 4296 to 11,457 | 500 (42.7%) |

| Characteristics related to the pandemic | |

| History of somatic diseases | |

| Yes | 154 (13.1%) |

| No | 1018 (86.9%) |

| COVID-19 infection of relatives and friends | |

| Yes | 8 (0.7%) |

| No | 1164 (99.3%) |

| History of SARS epidemic in 2003 | |

| Yes | 558 (47.6%) |

| No | 614 (52.4%) |

| Economic losses caused by COVID-19 (US dollars) | 1432 (0–2864) |

| Daily smoking | |

| Never smokes | 1052 (89.7%) |

| Has given up smoking | 37 (3.2%) |

| Smoking | 83 (7.1%) |

| Daily smoking consumption | |

| More than 15 cigarettes | 9 (10.8%) |

| 5–15 cigarettes | 34 (41.0%) |

| Less than 5 cigarettes | 40 (48.2%) |

| Did smoking increase during the pandemic? | |

| Yes | 25 (30.1%) |

| No | 58 (69.9%) |

| Daily drinking | |

| Never drinks | 904 (77.1%) |

| Has abstained from drinking | 56 (4.8%) |

| Drinking | 212 (18.1%) |

| Daily alcohol consumption | |

| More than 200 g | 7 (3.3%) |

| 100 g–200 g | 23 (10.8%) |

| Less than 200 g | 182 (85.9%) |

| Did drinking increase during the pandemic? | |

| Yes | 24 (11.3%) |

| No | 188 (88.7%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, Interquartile range; BMI, Body Mass Index; COVID-19, The 2019 coronavirus disease; SARS, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.

Most of the participants (86.9%) had no physical disease. Relatives or friends of 8 people (0.7%) were infected with COVID-19. Approximately half of the participants (47.6%) experienced the SARS epidemic in 2003. The median economic loss caused by COVID-19 was 1432 dollars.

A small number of the participants (10.3%) had the habit of smoking. Of these people, nearly half (48.2%) smoked less than 5 cigarettes a day, and some (30.1%) increased smoking during the pandemic. A small number of the participants (18.1%) had drinking habits. Of these people, most (85.9%) drank less than 200 g per day, and some (11.3%) drank more during the pandemic.

In addition, Table 2 shows the psychological characteristics of the participants. 18.8% of the participants reported current depressive symptoms, with a median PHQ-9 score of 4.0. Few people (13.3%) had significant symptoms of clinical anxiety, with a median GAD-7 score of 2.0. Few people (7.6%) reported mental health problems, with a median SCL-90 SOM score of 14.0. The majority (67.9%) felt moderate to high levels of perceived stress, with a median PSS-10 score of 16.0. The median CD-RISC-10 score was 27.0, with an IQR of 20.2–32.0. A total of 34 participants (2.8%) reported a high risk of suicidal ideation and behavior, with a median score of 0 for MINI suicidality module. A small number of the participants (7.2%) had clinically related insomnia, with a median ISI score of 3.0. The median ASDS score and PCL-5 score were 6.0 and 5.0, respectively. 7.0% of the participants had clinical PTSD symptoms. These scales (PHQ-9, GAD-7, SOM of SCL-90, PSS-10, CD-RISC-10, MINI suicidality module, ISI, ASDS, and PCL-5) demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency in this sample with α of 0.891, 0.933, 0.935, 0.719, 0.960, 0.773, 0.920, 0.874, and 0.966, respectively.

Table 2.

Participants’ psychological characteristics.

| Variable | N (%) / Median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Psychological depression | |

| PHQ-9 score (0–27 points) | 4.0 (1.0–8.0) |

| ≥10 | 220 (18.8%) |

| <10 | 952 (81.2%) |

| Psychological anxiety | |

| GAD-7 score (0–21 points) | 2.0 (0.0–6.0) |

| ≥8 | 156 (13.3%) |

| <8 | 1016 (86.7%) |

| Somatization | |

| SOM of SCL-90 score (12–60 points) | 14.0 (12.0–17.0) |

| ≥24 | 89 (7.6%) |

| <24 | 1083 (92.4%) |

| Psychological stress | |

| PSS-10 score (0–40 points) | 16.0 (12.0–19.0) |

| ≥14 | 796 (67.9%) |

| <14 | 376 (32.1%) |

| Psychological resilience | |

| CD-RISC-10 score (0–40 points) | 27.0 (20.2–32.0) |

| Suicidal ideation and behaviors | |

| MINI suicidality module score (0–33 points) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) |

| 0 | 1037 (88.5%) |

| 1–5 | 71 (6.1%) |

| 6–9 | 30 (2.6%) |

| ≥10 | 34 (2.8%) |

| Insomnia | |

| ISI score (0–28 points) | 3.0 (0.0–7.0) |

| ≥15 | 84 (7.2%) |

| <15 | 1088 (92.8%) |

| PTSD symptom severity | |

| ASDS score (0–28 points) | 6.0 (3.0–10.0) |

| PCL-5 score (0–80 points) | 5.0 (1.0–14.0) |

| ≥33 | 32 (7.0%) |

| <33 | 426 (93.0%) |

Abbreviations: IQR, Interquartile range; BMI, Body Mass Index; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7; SOM of SCL-90, somatization of Symptom Check List 90; PSS-10, Perceived Stress-10 Scale; CD-RISC-10, 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; ISI, 7-item Insomnia Severity Index; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; ASDS, Acute Stress Disorder Scale; PCL-5, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5.

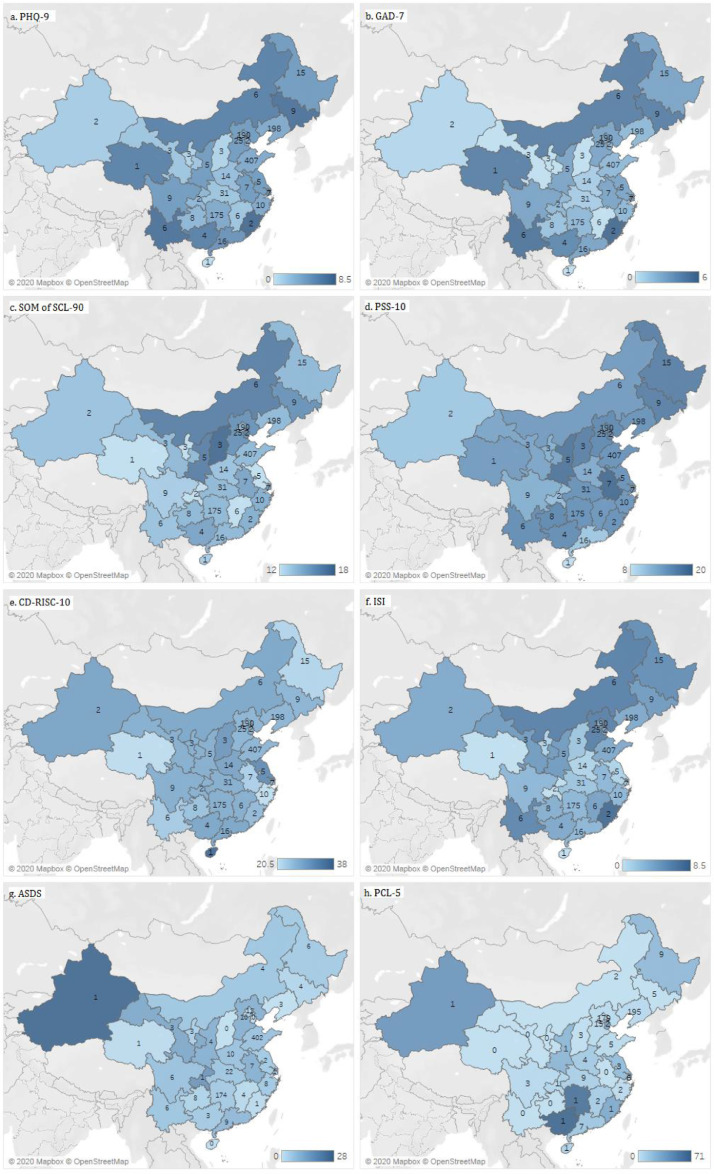

Respondents to the questionnaire lived in 30 provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities of China in the past two weeks. The distribution of the total score of each scale in different places of residence is shown in Fig. 2 . The darker the color is, the larger the median of the total score is. The figures in the Figure represent the number of participants in the questionnaire. Because the median score of MINI suicidality module score was zero, there was no corresponding map distribution. From this figure, we can see that psychological state of several provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities along the border of our country is relatively poor. Inner Mongolia, Jilin and Yunnan were more depressed than other provinces (a). Fujian, Jilin, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai and Yunnan were more anxious than others (b). Inner Mongolia, Shanxi and Shaanxi had more obvious somatization symptoms than others (c). Anhui, Heilongjiang, Jilin, Shaanxi and Shanxi had more significantly perceived stress than others (d). The psychological resilience of Heilongjiang, Qinghai and Zhejiang was lower than that of others (e). Fujian, Hebei and Inner Mongolia had more obvious symptoms of insomnia than other provinces (f). Guangxi, Hunan, Xinjiang, Gansu and Chongqing had more obvious symptoms of stress disorder than other provinces (g and h).

Fig. 2.

Geographical distribution of different mental states in China. Footnotes: 1. The darker the color is, the larger the median of the total score is. The figures in the Figure represent the number of participants in the questionnaire. 2. Out of the total of 1172 people, there were no participants from Tibet, Taiwan, Hongkong and Macao, so these areas are gray. 3. Because the median score of MINI suicidality module score was 0, there was no corresponding map distribution.4. Abbreviations: PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7; SOM of SCL-90, somatization of Symptom Check List 90; PSS-10, Perceived Stress-10 Scale; CD-RISC-10, 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; ISI, 7-item Insomnia Severity Index; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; ASDS, Acute Stress Disorder Scale; PCL-5, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5.

These data were collected from February 14, 2020 to March 29, 2020. The temporal distribution of the median total score of each scale is shown in Fig. 3 . Because the median score of MINI suicidality module score was zero, there was no corresponding temporal distribution. The data with a sample size of 1 on the same day was deleted in order to reflect the changes of mental state over time more objectively and truly. Fig. 3 showed that there were several days (February 20, February 24–26, and March 25) on which the public's mentality was relatively bad. March 25 was particularly worse, with a higher total score of all 8 scales.

Fig. 3.

Temporal distribution of different mental states in China. Footnotes: 1. Because the median score of MINI suicidality module score was 0, there was no corresponding temporal distribution. 2. The data with a sample size of 1 on the same day was deleted in order to reflect the changes of mental state over time more objectively and truly. 3. Abbreviations: PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7; SOM of SCL-90, somatization of Symptom Check List 90; PSS-10, Perceived Stress-10 Scale; CD-RISC-10, 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale; MINI, Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview; ISI, 7-item Insomnia Severity Index; PTSD, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; ASDS, Acute Stress Disorder Scale; PCL-5, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5.

4. Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first time in China to conduct a comprehensive descriptive analysis of the mental health status of the public after the long-term occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic, adopting nine commonly used scales to rate people's different mental status. We found that during the pandemic many smokers/drinkers increased their smoking/drinking. Further, during this period (February 14 to March 29), the incidence of mental disorders in China was comparatively low. Some provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities along the national border were more serious than other places. On March 25 and February 20, the mental health of the public was more serious than that on other days.

Our exploratory cross-sectional study showed that 30.1% of smokers increased smoking during the pandemic, while 11.3% of drinkers increased alcohol consumption during this period. Many scholars have proved that there is a significant association between anxiety disorder and smoking behavior (Cougle et al., 2010; Lasser et al., 2000). A previous review reported that 75% of studies showed positive relationship between alcohol consumption and social anxiety disorders (Cruz et al., 2017). Therefore, anxiety disorder may be a factor in people's choice of smoking and drinking. In addition, this pandemic has caused a median economic loss of 1432 dollars, which is bound to put pressure on people's lives, thereby increasing the consumption of cigarettes and alcohol.

In this study, it is noteworthy that the prevalence rates of most mental disorders were comparatively low: 18.8% for clinical depression, 13.3% for clinical anxiety, 7.6% for mental health problems, 2.8% for high risk of suicidal and behavior, 7.2% for clinical insomnia, and 7.0% for clinical PTSD symptom. However, moderate to high level of perceived stress was as high as 67.9%. The psychological resilience (the median score of CD-RISC-10 score was 27.0) was relatively good according to the cut-off of 23 (Blanco et al., 2019) or 25.5 (Ye et al., 2017). Interestingly, an earlier study from Liaoning Province in China found that one of the immediate mental effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on residents was mild stress (Zhang and Ma, 2020), which is consistent with our overall results. Another survey on the knowledge, attitude and behavior towards the COVID-19 pandemic during the sharply rise stage showed that the majority of the Chinese residents (97.1%) were confident that China can win the battle against COVID-19 (Zhong et al., 2020), which may explain why our research shows good psychological resilience. Moreover, a previous report on the psychological status of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic among 825 college students in Guangzhou found that 10.7% of them felt panic/depressed/emotional disturbed due to H1N1, while 14.9% were afraid of the WHO's H1N1 pandemic announcement (Gu et al., 2015). These are close to our incidences. The study also found that there was a significant correlation between the cognition of H1N1 and the mental disorders caused by H1N1. However, a recent literature reported that the incidence of mental disorders was high during COVID-19, with 53.8% of respondents experienced moderate or severe level of psychological effects (Wang et al., 2020a). According to the study, the incidence of depression, anxiety, and stress was as high as 30.3%, 36.4%, and 32.1%, respectively. Another study related to COVID-19 also reported psychological distress for up to 35% of respondents (Qiu et al., 2020). There may be some explanations for this difference. These studies on the psychological states of COVID-19 mainly focused on about two weeks (January 31 to February 14, 2020) after WHO declared the Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia of China as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Previous studies have shown that the announcement of WHO has a great impact on the public's psychology (Gu et al., 2015). However, our research period (February 14 to March 29) came two weeks after the announcement of WHO, when the pandemic in China was basically under control. Another point is that the psychological scales used in these studies are different, which leads to differences in the results of different studies. In addition, there is evidence that different levels of education (de Sousa et al., 2017), age composition (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2010), gender composition (Barefoot et al., 2001), marital status (Zhang and Ma, 2020), BMI (Jang and Lee, 2013), family income (Chung et al., 2018) and other factors are related to mental health status. Therefore, the demographic differences in the above studies may lead to inconsistencies with our study.

Furthermore, we found geographical differences in the mental health status. The psychological status of some provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities in the border was relatively more serious. To our best knowledge, there is very little research in this area. Similarly, a previous study focused on disaster survivors in Japan found that the psychological distress of survivors varied in different temporary housing communities (Matsuyama et al., 2016). This study also pointed out that social relations at the individual and community levels contributed to this difference. Considering the different prevention and control policies of different provinces/autonomous regions/municipalities during the COVID-19 pandemic, the contents and methods of related publicity were also different, resulting in regional differences. In addition, this study was carried out when the pandemic situation in China was basically under control, and also when the pandemic situation abroad was rapid and severe. Many cases imported from abroad were reported one after another. In these border provinces with more overseas imports, it is also possible to cause relatively poor psychological conditions.

In our study, we also found several special days when the public was in a relatively poor mental health status. On February 20, and 24–26, the psychological condition was relatively poorer. All negative scale medians were higher, while the median of CD-RISC-10 (psychological resilience scale) was lower. Looking up the news before and after these days, we found that the reason may be related to the news in the past few days. It was reported that on February 20, prison systems broke out in Shandong and Zhejiang provinces. On February 24, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Japan, South Korea and Italy rose, while the stock market plummeted. On February 26, several feverish people were found among overseas passengers flying to China. Interestingly, on the day of the worst mental state (March 25, 2020), the total score medians of all scales were high, including the psychological resilience scale. This may be related to the important notice issued by the Hubei Provincial COVID-19 Pandemic Prevention and Control headquarters on March 24. The notice said that the control of Hubei passageway (except Wuhan) will be lifted on March 25, and Wuhan will abolish the channel control measures on April 8. Hubei Province was the most serious pandemic place in China, especially in Wuhan City, where people across the country worried that deregulation will worsen another pandemic, thus they were in a bad psychological and emotional state. What's worse, another pandemic report said that 47 new confirmed cases were imported from abroad on March 24. This means that the number of new cases in China has been cleared, and the development of the domestic pandemic has basically been brought under control, but the situation of imported cases from abroad was becoming more and more serious. The notice and the news undoubtedly brought great worry and pressure to the general population. However, given the strong and effective control measures taken in China over the past two months, people were very confident that our country can win the final victory in the battle against the pandemic (Zhong et al., 2020). Therefore, the score of psychological resilience scale was high.

Several limitations of this current study should be mentioned here. First, due to the limitations of cross-sectional design itself, we cannot make causal inferences. Second, our study does not include the data from other countries, and cannot be extrapolated to the global psychological states. Different countries have different social and cultural backgrounds, and there are also great differences. Last but not least, although snowball sampling is more convenient to obtain samples, it is not representative enough to truly reflect the mental health status of the public in our country.

All in all, our results show that the prevalence rates of mental disorders in the Chinese population were relatively low nearly a month after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. More importantly, the development of the pandemic and the dynamics of real-time news affect the psychological status of the general population, therefore it is necessary to spread the information related to the pandemic openly, transparently and in a timely manner. People's poor psychological state will be alleviated when the government effectively controls the pandemic. In addition, some people increase the amount of smoking/drinking in order to relieve bad mental symptoms. If there is a significant increase in smoking/alcohol consumption in family members and friends, more attention should be paid to their bad mood, and guide them to relieve the psychological problems in a timely manner.

Contributors

Yali Ren and Wei Qian drafted the manuscript and analyzed and interpreted the data together. Xiangyang Zhang and Zhengkui Liu revised it critically for important intellectual content and made great contributions in conception and design of the study. Ruoxi Wang participated in the design of the research and the revision of the later manuscript. Yongjie Zhou, Ling Qi and Jiezhi Yang contributed to the acquisition of data. Xiuli Song, Lingyun Zeng and Zezhi Li have contributed to charting and related interpretation.

Role of the funding source

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants who participated in the study.

References

- Barefoot J.C., Mortensen E.L., Helms M.J. A longitudinal study of gender differences in depressive symptoms from age 50 to 80. Psychol. Aging. 2001;16:342–345. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.2.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco V., Guisande M.A., Sánchez M.T. Spanish validation of the 10-item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC 10) with non-professional caregivers. Aging Ment. Health. 2019;23:183–188. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1399340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L., Stein M.B. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J. Trauma Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castronovo V., Galbiati A., Marelli S. Validation study of the Italian version of the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) Neurol. Sci. 2016;37:1517–1524. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2620-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Dong D., He J. Psychometric properties of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) in Chinese undergraduates and depressive patients. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;261:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K.-.F., Kan K.K.-.K., Yeung W.-.F. Assessing insomnia in adolescents: comparison of insomnia severity index, athens insomnia scale and sleep quality index. Sleep Med. 2011;12:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung R.Y.-.N., Chung G.K.-.K., Gordon D. Deprivation is associated with worse physical and mental health beyond income poverty: a population-based household survey among Chinese adults. Qual. Life Res. 2018;27:2127–2135. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1863-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle J.R., Zvolensky M.J., Fitch K.E., Sachs-Ericsson N. The role of comorbidity in explaining the associations between anxiety disorders and smoking. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2010;12:355–364. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz ELDd, Martins PDdC, Diniz P.R.B. Factors related to the association of social anxiety disorder and alcohol use among adolescents: a systematic review. J. Pediatr. (Rio J.) 2017;93:442–451. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen W., Gulati G., Kelly B.D. Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM. 2020 doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa R.D., Rodrigues A.M., Gregorio M.J. Anxiety and depression in the portuguese older adults: prevalence and associated factors. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 2017;4:196. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2017.00196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fau D.L., Lipman R.S., Covi L. SCL-90: an outpatient psychiatric rating scale–preliminary report. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1973;9:13–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo A., Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psychiatry. 2020;63:e32. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin R., Haque S., Neto F., Myers L.B. Initial psychological responses to Influenza A, H1N1 ("Swine flu") BMC Infect. Dis. 2009;9:166. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J., Zhong Y., Hao Y. Preventive behaviors and mental distress in response to H1N1 among university students in Guangzhou, China. Asia Pac. J. Public Health. 2015;27 doi: 10.1177/1010539512443699. NP1867-NP1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo B., Kaylor-Hughes C., Garland A. Factor structure and longitudinal measurement invariance of PHQ-9 for specialist mental health care patients with persistent major depressive disorder: exploratory structural equation modelling. J. Affect. Disord. 2017;219:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F., Wang H., Wang Z. Psychometric properties of the perceived stress scale in a community sample of Chinese. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:130. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02520-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A.J., Dunn K.M., Chaffee T. Diagnostic and clinical utility of the GAD-2 for screening anxiety symptoms in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2018;99:2045–2049. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang M.H., Lee G. Body image dissatisfaction as a mediator of the association between BMI, self-esteem and mental health in early adolescents: a multiple-group path analysis across gender. J. Korean Acad. Nurs. 2013;43:165–175. doi: 10.4040/jkan.2013.43.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger-Gottschalk A., Knaevelsrud C., Rau H. The German version of the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): psychometric properties and diagnostic utility. BMC Psychiatry. 2017:379.. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1541-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L., Williams J.B.W. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K., Boyd JW Fau, Woolhandler S., Woolhandler S Fau, Himmelstein D.U. Smoking and mental illness: a population-based prevalence study. JAMA. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau J.T., Griffiths S., Choi K.C., Tsui H.Y. Avoidance behaviors and negative psychological responses in the general population in the initial stage of the H1N1 pandemic in Hong Kong. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010;10:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P., Wang F., Ji G-z. The psychological results of 438 patients with persisting GERD symptoms by symptom checklist 90-revised (SCL-90-R) questionnaire. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9783. doi: 10.1097/.0000000000009783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Li W., Yang Y., Liu Z.H. Progression of mental health services during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:1732–1738. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim A.-.Y., Lee A.-.R., Hatim A. Clinical and sociodemographic correlates of suicidality in patients with major depressive disorder from six Asian countries. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maske U.E., Buttery A.K., Beesdo-Baum K. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-IV-TR major depressive disorder, self-reported diagnosed depression and current depressive symptoms among adults in Germany. J. Affect. Disord. 2016:190. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama Y., Aida J., Hase A. Do community- and individual-level social relationships contribute to the mental health of disaster survivors?: a multilevel prospective study after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016;151:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C.M. The Guiford Press; 1996. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management. [Google Scholar]

- Page L.A., Seetharaman S., Suhail I. Using electronic patient records to assess the impact of swine flu (influenza H1N1) on mental health patients. J. Ment. Health. 2011;20:60–69. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2010.542787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng E.Y.-.C., Lee M.-.B., Tsai S.-.T. Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: an example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2010;109:524–532. doi: 10.1016/s0929-6646(10)60087-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J., Shen B., Zhao M. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen. Psychiatr. 2020;33 doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanche S., Lin Y.T., Xu C. High contagiousness and rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200282. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H. The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. quiz 34-57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. Cambridge Scholars Publishing; Newcastle upon Tyne: 2019. The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease. [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Pan R., Wan X. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:1660–4601. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729. (Electronic) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F.W., Litz B.T., Keane T.M. et al. The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). The national center for PTSD; 2013. p Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp#obtain.

- WHO. Coronavirus (COVID-19) World Health Organization; 2020. https://who.sprinklr.com/.

- Wiriyakijja P., Porter S., Fedele S. Validation of the HADS and PSS-10 and a cross-sectional study of psychological status in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020;49:260–270. doi: 10.1111/jop.12991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K.B., Castriotta N., Lenze E.J. Anxiety disorders in older adults: a comprehensive review. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:190–211. doi: 10.1002/da.20653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Z.J., Qiu H.Z., Li P.F. Validation and application of the Chinese version of the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-10) among parents of children with cancer diagnosis. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017;27:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Tam W.W.S., Wong P.T.K. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for measuring depressive symptoms among the general population in Hong Kong. Compr. Psychiatry. 2012;53:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Wan C., Huebner E.S. Psychometric properties of the symptom check list 90 (SCL-90) for Chinese undergraduate students. J. Ment. Health. 2019;28:213–219. doi: 10.1080/09638237.2018.1521939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Ma Z.F. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020;17:2381. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17072381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong B.L., Luo W., Li H.M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese residents during the rapid rise period of the COVID-19 outbreak: a quick online cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:1745–1752.. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]