Abstract

Background:

Long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain arose amid limited availability and awareness of other pain therapies. Though many complementary and integrative health (CIH) and nondrug therapies are effective for chronic pain, little is known about CIH/nondrug therapy use patterns among people prescribed opioid analgesics.

Objectives:

To estimate patterns and predictors of self-reported CIH/nondrug therapy use for chronic pain within a representative national sample of U.S military veterans prescribed long-term opioids for chronic pain.

Research Design:

National two-stage stratified random sample survey combined with electronic medical record data. Data were analyzed using logistic regressions and latent class analysis.

Subjects:

U.S. military veterans in Veterans Affairs (VA) primary care who received >=6 months of opioid analgesics.

Measures:

Self-reported use of each of ten CIH/nondrug therapies to treat or cope with chronic pain in the past year: meditation/mindfulness, relaxation, psychotherapy, yoga, t’ai chi, aerobic exercise, stretching/strengthening, acupuncture, chiropractic, massage; Brief Pain Inventory-Interference (BPI-I) scale as a measure of pain-related function.

Results:

8,891(65%) of 13,660 invitees completed the questionnaire. 80% of veterans reported past-year use of at least one non-drug therapy for pain. Younger age and female sex were associated with use of most non-drug therapies. Higher pain interference was associated with lower use of exercise/movement therapies. Nondrug therapy use patterns reflected functional categories (psychological/behavioral, exercise/movement, manual).

Conclusion:

Use of CIH/nondrug therapies for pain was common among patients receiving long-term opioids. Future analyses will examine non-drug therapy use in relation to pain and quality of life outcomes over time.

Keywords: chronic pain, veterans, opioids, non-drug therapy, complementary and integrative health

Introduction

Long-term opioid therapy (LTOT) is associated with high morbidity and mortality1–3 and little evidence supports its effectiveness for chronic pain.4 Current guidelines for many chronic pain conditions recommend avoiding opioids for chronic pain and using nondrug therapies as first line treatment.5–9 For patients already on long-term opioid therapy, guidelines recommend working with patients to reduce opioids and incorporate nondrug therapies.10,11 In practice, however, opioids remain overprescribed and nondrug therapies underused for chronic pain. Overprescribing of opioids for chronic pain in the U.S. and Canada has been described as a marker of inadequate pain management resources overall.12

Many non-drug therapies have demonstrated effectiveness in improving functional outcomes in chronic pain, though evidence varies for specific therapies and conditions, and multimodal care may be most effective.13–15 Non-drug therapies comprise functional categories such as psychological or behavioral (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy), movement-based (e.g., exercise therapy), or manual (e.g., spinal manipulation), and can be either self-directed or practitioner-delivered.16 Non-drug therapies include many complementary and integrative health (CIH) therapies such as acupuncture, yoga, and t’ai chi. Although “complementary” initially described health practices with origins in other health traditions outside the biomedical health system,17 CIH therapies are increasingly integrated into mainstream health practice in the U.S.18–20 Little is known about the extent and predictors of non-drug therapy use for pain among people currently prescribed LTOT.

The U.S. Veterans Health Administration (VA) continues to develop novel approaches to interdisciplinary pain therapy, with emphasis on non-drug modalities including behavioral therapy, physical rehabilitation and CIH therapies.16,20 Understanding how veterans use non-drug therapies is an important step toward understanding demand and opportunities to improve access within VA, especially for veterans on LTOT who may benefit from more effective and safe treatment options.

The purpose of this study is to identify patterns of CIH and non-drug therapy use within a national sample of VA primary care patients on LTOT for chronic pain, and to evaluate associations of patient characteristics with type of non-drug therapy use.

Methods

Study population and sampling

Survey and administrative data were collected as part of the Evaluating Prescription Opioid Changes in Veterans (EPOCH) study, a prospective longitudinal cohort of VA primary care patients prescribed LTOT for chronic pain in 2016. The EPOCH study used a two-stage stratified random sampling design. Eligibility criteria for patients included current LTOT and at least one primary care clinic appointment during the 12 months preceding the most recent opioid dispensing date. Current LTOT was defined as 1) a qualifying opioid analgesic dispensed within the prior 30 days and 2) ≥150 days’ supply of a qualifying opioid in the 180 days before the most recent dispensing date with no between-fill gaps >40 days. Qualifying opioid analgesics were on the VA formulary and indicated for pain, not including tramadol or buprenorphine. Eligibility criteria were assessed using monthly extractions of administrative data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW).

To limit the sample to patients receiving LTOT for chronic pain rather than other reasons (such as opioid use disorder or palliative care with limited life expectancy), exclusion criteria included any of the following over the preceding year: oncology, radiation oncology, hospice, or palliative care visit; dementia diagnosis or dementia clinic visit; adult day care; nursing home stay; or opioid addiction treatment program visit.

Selected patients were contacted and invited to participate. Data were collected from participants via mailed paper or telephone annual surveys. Patients were contacted in seven waves (total contacted N=14,160), including an initial embedded pilot survey wave (pilot contacted N= 500). Minor changes to the questionnaire were made after the embedded pilot was completed. Because these changes involved measures that are the focus of this report, we used data for the main six survey waves, excluding pilot data. The response rate was 65% for the overall survey cohort (9,253 responded/14,160 contacted) and for the main cohort excluding the pilot (8,891 responded/13,660 contacted). Additional details of EPOCH study design, methods, and survey response have been described elsewhere.21 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Minneapolis VA Health Care System.

Patient-reported survey measures

Non-drug and CIH therapy measures

EPOCH survey questions about CIH and non-drug therapy use were modified from the Pain Management Inventory (PMI).22 The PMI, a checklist of non-drug conventional and complementary therapies used in pain management, was designed to facilitate standardized self-reported therapy use comparable across studies. PMI therapy descriptions were based on items used in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) complementary medicine supplement23 and refined through cognitive interviews with patients and key informant interviews with pain clinicians. EPOCH survey descriptions of therapies are outlined in Table 1. Questionnaires included questions about each of ten therapies and practices they “may have used to treat or cope with pain in the past year.” For each therapy or practice, participants were asked to “choose the one answer that best describes your use in the past year” from five categories: did not use in past year, a few times, monthly, weekly, or most days.

Table 1.

Complementary, integrative and non-drug pain therapies assessed in the Effects of Prescription Opioid Changes for veterans (EPOCH) survey.

| Functional category | Therapy | Description provided in survey |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological/ behavioral | Psychotherapy | Cognitive, behavioral or psychological therapy: One-on-one or group talk therapy by a psychologist or other mental health provider |

| Mindfulness or meditation | Meditation or mindfulness practice: Use of focused attention and non-judgmental awareness including Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) | |

| Relaxation | Relaxation techniques: Breathing techniques, guided imagery, or progressive muscle relaxation | |

| Exercise/ movement | Yoga | Practices that combine physical postures, breathing techniques, and mental focus |

| t’ai chi | Combined practice of slow movements, coordinated breathing, and mental focus | |

| Stretching/ strengthening | Exercise with stretches or weights on your own, in a group, or directed by a physical therapist or trainer | |

| Aerobic exercise | Activities such as walking, swimming or aerobics on your own, in a group, or directed by a physical therapist or trainer | |

| Manual | Acupuncture | Stimulation of specific points of the body with thin needles |

| Chiropractic | Hands on adjustment of spine and joints | |

| Massage | Hands on pressure, rubbing, or manipulation of muscles and soft tissues |

Pain-related functional interference

Pain-related functional interference was assessed with the Brief Pain Inventory-Interference (BPI-I) scale.24,25 The BPI-I assesses pain-related functional interference over the preceding week in seven domains rated on a scale of 0 (“does not interfere”) to 10 (“completely interferes”). An overall BPI-I score was calculated as the mean of the seven item scores (range 0–10). For analyses, BPI-I was categorized as “mild” (0–3), “moderate” (4–6) or “severe” (7–10).

Administrative data measures

Demographic and health-related measures

Patient demographic information including age, sex, and race were obtained from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Mental health diagnoses were assessed through inpatient and outpatient International Classification of Diseases (ICD) Ninth-Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)26 and Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM)27 codes obtained from the CDW and categorized into diagnostic groups including depressive disorders, PTSD, and non-PTSD anxiety disorders. The Charlson comorbidity index28 of chronic disease burden was calculated by extracting included diagnoses from the CDW.

Opioid dose

Opioid doses were calculated using dispensing data from VA outpatient pharmacies and converted to morphine-equivalent (ME) milligrams (mg) per day via conversion factors recommended by the CDC.29 To determine average daily dose for each participant, the total mg for all opioids dispensed in six months (including the index prescription) was calculated then divided by the number of days from the first opioid dispensed to the end of the most recent prescription days’ supply. Categorical analyses considered daily dosage in ME mg/day according to the following conventional research categories: low (<20), moderate (20 to <50), high (50 to <100), or very high (≥100).30–32

Statistical analysis

To allow comparison across therapies, frequency of use for each individual non-drug therapy was dichotomized as any past-year use or no past-year use. Therapies were categorized within functional categories cited in the literature: psychological/behavioral, exercise/movement, and manual therapies (Table 1).16 Frequencies of past year use of any non-drug therapy, each functional category of non-drug therapy, and each individual non-drug therapy were calculated and presented as observed unweighted counts. Percentages were calculated with survey weights as appropriate for the sampling design.21

To estimate associations between individual characteristics and use of individual non-drug therapies, multivariable logistic regressions were estimated separately for each therapy. Past-year use vs. non-use of an individual therapy for pain was the dependent variable in each regression. Independent variables included age (categorical: <55, 55–64, 65–74, 75+), sex (male, female), race (white, black, other), BPI-I category (mild, moderate, severe), opioid daily dose in ME mg/day (<20, 20 to <50, 50 to <100, 100+), Charlson comorbidity index (continuous), depressive disorder diagnosis (present vs. absent), anxiety disorder diagnosis (present vs. absent), and PTSD diagnosis (present vs absent). As past-year use was common for several therapies, results of the logistic models were used to estimate adjusted risk differences and 95% confidence intervals.33

To explore patterns of non-drug therapy use, we used latent class analysis (LCA)34 to identify groups with similar past-year use patterns. Past-year use of individual non-drug therapies were the only indicators used to determine latent classes in LCA models. Yoga and t’ai chi were not included in the LCA models because the low prevalences created estimability problems. We explored 3, 4, 5 and 6-class solutions to the model. The final class solution was determined based on interclass heterogeneity, fit statistics, class size and clinical interpretability.34,35 After a final LCA model was identified, participants were assigned to a single latent class based on highest posterior probability of membership. A multinomial logistic regression model was estimated with class membership as the dependent variable. Independent variables were dichotomized for ease of model interpretation: age (<65, 65+), sex (male, female), race (white, not white), BPI-I (not severe, severe), opioid daily dose in ME mg/day (<100, 100+), Charlson comorbidity index (0–2, 3+), depressive disorder diagnosis (present vs. absent), anxiety disorder diagnosis (present vs. absent), and PTSD diagnosis (present vs. absent). Risk differences were calculated from multinomial logistic regression results.

Survey weights were applied to analyses to account for the two-stage stratified sampling approach.21 As LCA models could not be fit using survey weights, survey weights were applied at the phase of multinomial logistic regressions assessing posterior probability of class membership. We did not adjust alpha levels for multiple comparisons because this was an exploratory analysis not intended to test specific hypotheses.

All analyses were performed in Stata Version 15.36

Results

Prevalence of non-drug and CIH therapy use

Use of at least one of 10 non-drug therapies was reported by 80.1% (N=6978) of the cohort. Table 2 presents frequencies of self-reported past-year use of any functional category of non-drug therapy and of each of the 10 non-drug therapies individually. The most commonly used individual therapies were stretching/strengthening exercise (55.9%), aerobic exercise (38.2%), and relaxation techniques (35.7%). All non-drug therapy use variables had <4% missing data.

Table 2.

Frequency of past-year non-drug therapy use for pain among patients on long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. Percentages were calculated with survey weights. N is the observed unweighted count. Total sample size: 8,891.

| Non-drug therapy | % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Any psychological/behavioral use | 47.9 | 4,278 |

| Psychotherapy | 27.7 | 2,428 |

| Mindfulness or meditation | 19.8 | 1,749 |

| Relaxation | 35.7 | 3,122 |

| Any exercise/movement use | 64.5 | 5,792 |

| Aerobic exercise | 38.2 | 3,542 |

| Stretching/strengthening | 55.9 | 5,101 |

| Yoga | 6.4 | 568 |

| t’ai chi | 5.1 | 402 |

| Any manual use | 32.2 | 2,913 |

| Acupuncture | 9.5 | 957 |

| Chiropractic | 14.8 | 1,243 |

| Massage | 18.9 | 1,737 |

Factors associated with individual non-drug and CIH therapy use

Table 3 presents factors associated with past-year use of individual non-drug therapies for pain in multivariable logistic regression analyses. Measures presented have an absolute value range of 0–1 and represent probability differences of reported therapy use as compared to the noted reference group. For example, people aged 75 years or older had 0.18 (18%) lower probability of reporting past-year use of psychotherapy for pain than people aged under 55. Patients aged 65 and older were less likely than patients under 55 to report using every non-drug therapy except t’ai chi and chiropractic care. Women were more likely than men to report use of therapies other than t’ai chi and chiropractic care, most notably meditation, relaxation, stretching/strengthening, aerobic exercise, yoga, and massage. Patients reporting severe pain interference were less likely than patients reporting mild pain interference to report use of stretching/strengthening or aerobic exercise, and more likely than patients reporting mild pain interference to report use of acupuncture or massage. Patients with opioid doses of 100 ME mg/day or higher were more likely than patients with opioid doses under 20 ME mg/day to report use of meditation and relaxation. Veterans diagnosed with PTSD were more likely to report use of any psychological/behavioral therapy.

Table 3.

Factors associated with past-year use of individual complementary, integrative and non-drug therapies for pain. Results are presented as risk differences (RD) calculated from multivariable logistic regressions. Analyses adjusted for all listed variables and for Charlson comorbidity index, which as a continuous variable was not associated with use of any non-drug therapy. BPI-I: Brief Pain Inventory–Interference. ME: Morphine equivalent, milligrams/day.

| Psychological / behavioral therapies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychotherapy RD (95% CI) |

Meditation RD (95% CI) |

Relaxation RD (95% CI) |

||

| Age Ref: <55 | ||||

| 55–64 | −0.054 (−0.11, 0.0031) | −0.080 (−0.15, −0.012) | −0.10 (−0.17, −0.035) | |

| 65–74 | −0.13 (−0.19, −0.070) | −0.16 (−0.23, −0.091) | −0.21 (−0.28, −0.14) | |

| 75+ | −0.18 (−0.25, −0.11) | −0.21 (−0.28, −0.14) | −0.30 (−0.37, −0.23) | |

| Sex Ref: Male | ||||

| Female | 0.049 (−0.014, 0.11) | 0.11 (0.039, 0.18) | 0.13 (0.046, 0.21) | |

| Race Ref: White | ||||

| Black | 0.063 (0.011, 0.12) | −0.010 (−0.057, 0.037) | −0.034 (−0.089, 0.020) | |

| Other | 0.035 (−0.019, 0.089) | −0.014 (−0.063, 0.035) | 0.033 (−0.035, 0.10) | |

| BPI-I Ref: Mild | ||||

| Moderate | 0.010 (−0.057, 0.078) | −0.038 (−0.11, 0.037) | 0.012 (−0.060, 0.082) | |

| Severe | 0.020 (−0.050, 0.090) | −0.066 (−0.14, 0.0094) | −0.030 (−0.10, 0.043) | |

| Opioid dose (ME) | ||||

| Ref: <20 | ||||

| 20 - <50 | −0.010 (−0.045, 0.025) | 0.030 (−0.0067, 0.068) | 0.024 (−0.019, 0.068) | |

| 50 - <100 | 0.016 (−0.039, 0.070) | 0.059 (−0.0017, 0.11) | 0.029 (−0.039, 0.096) | |

| 100+ | 0.032 (−0.017, 0.080) | 0.088 (0.030, 0.15) | 0.13 (0.064, 0.19) | |

| Depressive disorder | 0.23 (0.18, 0.28) | 0.044 (0.00086, 0.088) | 0.079 (0.029, 0.13) | |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.19 (0.13, 0.24) | 0.040 (−0.021, 0.10) | 0.096 (0.033, 0.16) | |

| PTSD | 0.27 (0.21, 0.33) | 0.13 (0.067, 0.18) | 0.12 (0.063, 0.18) | |

| Exercise / movement therapies | ||||

| Aerobic exercise RD (95% CI) |

Stretching/ strengthening RD (95% CI) |

Yoga RD (95% CI) |

t’ai chi

RD (95% CI) |

|

| Age Ref: <55 | ||||

| 55–64 | 0.013 (−0.058, 0.085) | −0.068 (−0.14, 0.0051) | −0.0011 (−0.042, 0.040) | 0.012 (−0.020, 0.044) |

| 65–74 | −0.086 (−0.16, −0.015) | −0.15 (−0.23, −0.077) | −0.040 (−0.075, −0.0042) | −0.037 (−0.029, −0.037) |

| 75+ | −0.12 (−0.21, −0.034) | −0.18 (−0.27, −0.083) | −0.048 (−0.085, −0.0098) | 0.0093 (−0.030, 0.048) |

| Sex Ref: Male | ||||

| Female | 0.15 (0.064, 0.23) | 0.094 (0.016, 0.17) | 0.072 (0.023, 0.12) | 0.015 (−0.016, 0.045) |

| Race Ref: White | ||||

| Black | 0.030 (−0.028, 0.088) | −0.021 (−0.084, 0.041) | 0.013 (−0.018, 0.045) | 0.027 (−0.030, 0.057) |

| Other | 0.082 (0.011, 0.15) | 0.065 (−0.013, 0.14) | −0.0031 (−0.032, 0.026) | 0.032 (−0.0097, 0.074) |

| BPI-I Ref: Mild | ||||

| Moderate | −0.082 (−0.15, −0.0091) | −0.041 (−0.10, 0.021) | −0.0084 (−0.046, 0.029) | 0.013 (−0.015, 0.040) |

| Severe | −0.20 (−0.28, −0.13) | −0.16 (−0.22, −0.094) | −0.015 (−0.040, 0.020) | −0.020 (−0.045, 0.056) |

| Opioid dose (ME) | ||||

| Ref: <20 | ||||

| 20 - <50 | 0.0046 (−0.043, 0.052) | −0.033 (−0.088, 0.023) | 0.010 (−0.0093, 0.030) | 0.018 (−0.00025, 0.037) |

| 50 - <100 | 0.017 (−0.056, 0.090) | −0.038 (−0.12, 0.044) | −0.0034 (−0.028, 0.021) | 0.025 (−0.0068, 0.056) |

| 100+ | 0.017 (−0.048, 0.083) | 0.032 (−0.042, 0.10) | 0.052 (−0.0047, 0.11) | 0.014 (−0.0076, 0 036) |

| Depressive disorder | 0.0097 (−0.042, 0.061) | 0.026 (−0.028, 0.081) | 0.016 (−0.013, 0.045) | 0.010 (−0.014, 0.034) |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.030 (−0.041, 0.10) | −0.011 (−0.090, 0.068) | −0.0090 (−0.037, 0.019) | 0.040 (0.00083, 0.078) |

| PTSD | 0.033 (−0.034, 0.10) | 0.028 (−0.040, 0.096) | 0.037 (0.0043, 0.070) | 0.045 (0.010, 0.080) |

| Manual therapies | ||||

| Acupuncture RD (95% CI) |

Chiropractic RD (95% CI) |

Massage RD (95% CI) |

||

| Age Ref: <55 | ||||

| 55–64 | −0.029 (−0.069, 0.010) | −0.071 (−0.13, −0.01) | −0.072 (−0.13, −0.017) | |

| 65–74 | −0.048 (−0.086, −0.0094) | −0.067 (−0.14, 0.0023) | −0.085 (−0.15, −0.024) | |

| 75+ | −0.049 (−0.093, −0.0049) | −0.084 (−0.15, −0.014) | −0.081 (−0.16, −0.0041) | |

| Sex Ref: Male | ||||

| Female | 0.037 (−0.015, 0.089) | −0.0094 (−0.052, 0.033) | 0.078 (0.015, 0.14) | |

| Race Ref: White | ||||

| Black | 0.034 (0.0020, 0.067) | −0.030 (−0.067, 0.0077) | 0.029 (−0.018, 0.075) | |

| Other | 0.045 (−0.0096, 0.10) | 0.032 (−0.049, 0.11) | 0.041 (−0.023, 0.11) | |

| BPI-I Ref: Mild | ||||

| Moderate | 0.026 (−0.0023, 0.055) | −0.011 (−0.058, 0.036) | 0.049 (0.013, 0.085) | |

| Severe | 0.037 (0.0090, 0.065) | 0.0021 (−0.053, 0.057) | 0.050 (0.0061, 0.093) | |

| Opioid dose (ME) | ||||

| Ref: <20 | ||||

| 20 - <50 | −0.0050 (−0.031, 0.021) | 0.014 (−0.021, 0.050) | −0.013 (−0.054, 0.028) | |

| 50 - <100 | 0.0069 (−0.027, 0.041) | 0.045 (−0.041, 0.13) | −0.056 (−0.10, −0.012) | |

| 100+ | 0.053 (0.00045, 0.11) | −0.013 (−0.066, 0.041) | −0.016 (−0.071, 0.039) | |

| Depressive disorder | 0.0039 (−0.0247, 0.032) | −0.049 (−0.096, −0.0021) | −0.036 (−0.076, 0.0035) | |

| Anxiety disorder | 0.00093 (−0.032, 0.034) | −0.0027 (−0.052, 0.046) | 0.017 (−0.032, 0.066) | |

| PTSD | 0.014 (−0.018, 0.046) | 0.085 (0.0015, 0.17) | 0.025 (−0.033, 0.083) | |

Latent classes of non-drug therapy use patterns

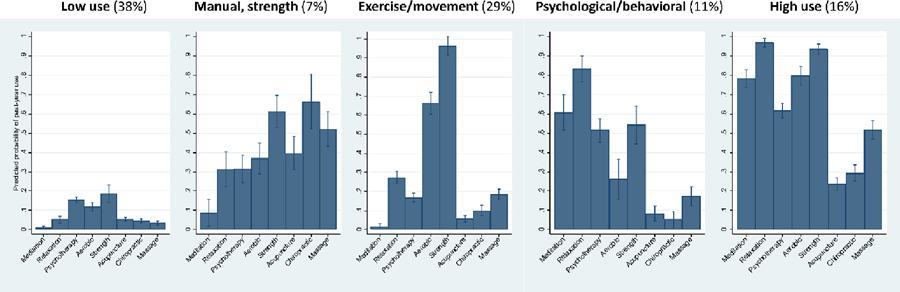

We determined that a five-class model was the best latent class solution based on interclass heterogeneity, fit statistics, and clinical impressions of relevant classes. Classes represented distinct patterns of non-drug therapy use, which we named according to how we perceived their unique characteristics: low use, manual/strength, exercise/movement, psychological/behavioral, and high use. The five-class solution offered additional classes with distinct therapy use patterns over those available in the three-class and four-class solutions, in addition to gains in fit statistics. Use patterns appeared somewhat robust, as similar use classes were evident across multiple latent class solutions. The low-use, exercise/movement and high-use classes were apparent in the three-class and four-class solutions, and the four-class solution yielded an additional class analogous to the manual/strength class. The six-class solution did not identify a substantively meaningful different additional class beyond those available in the five-class solution.

Figure 1 displays the probability of past-year use of each individual non-drug therapy within each latent class. Patients in the low-use class (38% of the cohort) had low likelihood of past-year use of each non-drug therapy for pain (between 1% and 19%). The manual/strength class (7% of cohort) was characterized by higher use of acupuncture (40%) and chiropractic (66%) therapy than any other class, higher use of massage (52%) than any class except the overall high-use class, and relatively high use of stretching/strengthening (61%). The exercise/movement class (29% of cohort) was characterized by almost universal use of stretching/strengthening (96%) and high use of aerobic exercise (66%), with lower use of other therapies (2–27%). The psychological/behavioral class (11% of cohort) was characterized by high use of relaxation (83%), meditation (61%) and psychotherapy (52%) as well as stretching/strengthening (54%), with lower use of other therapies (5–26%). The high-use class (16% of cohort) was characterized by almost universal use of relaxation (97%) and stretching/strengthening (94%), high use of aerobic exercise (80%), meditation (78%) and psychotherapy (62%), and higher use of massage (52%) than all classes except the manual/strength class.

Figure 1.

Probability of past-year use of individual non-drug therapies for pain among people on long-term opioid therapy, by latent class. Probability range: 0–1. Percentages represent the percent of people with maximum probability of membership in each class.

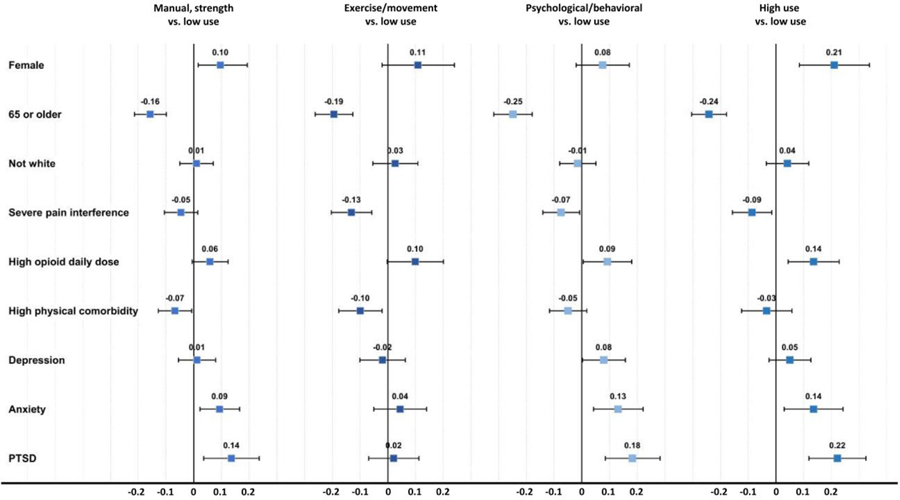

Figure 2 presents patient characteristics associated with differences in probability of membership in each of the four active classes (i.e., manual/strength, exercise/movement, psychological/behavioral, and high use) relative to the low-use class. Measures presented have an absolute value range of 0–1 and represent probability differences of membership in a non-drug therapy use class compared to membership in the low-use class. For example, being female was associated with a 0.25 (25%) greater prevalence of the high-use class than the low-use class. Being 65 or older was associated with lower probability of membership in each active class relative to the low-use class, whereas female sex and high opioid daily dose were associated with higher probability of membership in each of the active classes. Severe pain interference was associated with higher probability of membership in the low-use class than in the exercise/movement and high-use classes. Higher medical comorbidity was associated with higher probability of membership in the low-use class than in the exercise/movement or manual/strength classes. Anxiety and PTSD were associated with higher probability of membership in the manual/strength, psychological/behavioral, and high-use classes, while depression was only associated with higher probability of psychological/behavioral class membership.

Figure 2.

Difference in probability of membership in each non-drug therapy use class, vs. membership in low-use class, by patient characteristics. Probability range: 0–1 (absolute value). Severe pain interference: Brief Pain Inventory-Interference ≥ 7. High opioid daily dose: ≥ 100 morphine-equivalent mg/day. High physical comorbidity: Charlson Comorbidity Index ≥ 3 (80th percentile). PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Some patient characteristics also distinguished active use classes from one another. Being female was associated with higher probability of membership in the high-use class than in every class other than exercise/movement. Severe pain interference was less associated with exercise/movement class membership than with membership in any class other than high-use, and PTSD was less associated with exercise/movement class membership than with membership in any class other than low-use. Depression was more positively associated with psychological/behavioral class membership than with membership in any class other than high-use.

Discussion

We found that a large majority of U.S. VA primary care patients on long-term opioid therapy reported use of non-drug therapies for pain. Younger patients and female patients were more likely to use most non-drug therapies, and patients with severe pain interference were less likely to use exercise/movement therapies. Observed non-drug therapy use patterns derived from latent class analysis were largely consistent with clinically relevant functional categories of psychological/behavioral, exercise/movement, and manual therapies.

Broadly, our findings regarding non-drug therapy use for pain among patients on long-term opioid therapy are consistent with previous research. In one study of patients with a past-year musculoskeletal pain diagnosis prescribed at least 90 days of opioid therapy, 71% of 517 patients reported non-drug therapy use for pain in the preceding 6 months.37 An earlier study of 908 primary care patients in Wisconsin with continuous pain for 3 months and prescribed opioids found that 44% reported CIH therapy use for pain in the past 12 months, with overall use more common among younger patients, women, and patients with higher pain intensity and disability.38 To our knowledge, these are the only prior studies of non-drug therapy use patterns among people on opioid therapy for pain.

Larger observational studies that used VA administrative data to explore patterns of CIH and non-drug therapy use among people with chronic pain similarly found use to be more common among younger patients and women.39,40 These studies found lower non-drug therapy use prevalence than studies that assessed use via self-report, presumably because people often access non-drug therapies outside health systems.41

The finding that younger patients and women were more likely to use most types and combinations of non-drug and CIH therapies is consistent with past research in general U.S. populations,42–44 and may relate to cultural norms and patient and provider beliefs. For example, female patients in our cohort were more likely to have used yoga for pain, though yoga use was rare overall. Although 60% of yoga users perceived yoga as helpful for pain in a recent study of veterans with chronic pain on LTOT,37 other research has suggested many veterans see yoga as a therapy “for girls.”45,46 Engaging with patient and provider beliefs about who can and should engage in certain therapy types may increase accessibility.

A prior study conducted a latent class analysis of non-drug and CIH therapy use (for any purpose) using data from a cohort of U.S. Minnesota National Guard veterans.47 Patients in that study were younger (mean age 39) and mostly without chronic pain or opioid use. Results demonstrated similar observed categories of non-drug therapy use, despite differences in study populations and reasons for CIH use.

We found that patients with worse pain interference with function were less likely to have engaged in exercise and movement therapies, particularly aerobic and stretching/strengthening exercise. Although this cross-sectional analysis cannot determine cause and effect, prior research suggests reasons for a connection between exercise and better pain-related function. Lower levels of physical activity are a risk factor for developing chronic pain.48 Exercise interventions have been shown to prevent future pain and improve outcomes in patients with established chronic pain.10,14 Investigating and targeting factors that facilitate use of exercise/movement therapy among people with worse pain interference may be of particular benefit.

Mental health diagnoses were positively associated with use of psychological and behavioral therapies. This could reflect increased access to treatments often delivered by mental health clinicians, or greater comfort seeking out psychological resources. The existence of a mental health diagnosis in the chart may itself be a proxy for access to relevant therapies.

Patterns of use derived from latent class analysis were found to reflect previously cited functional categories (i.e., psychological/behavioral, exercise/movement, and manual therapies). While several patient characteristics distinguished low-use classes from other active use classes, few differed meaningfully between active use classes, suggesting that factors unmeasured in these data may drive distinct patterns of non-drug therapy use. Differences among use patterns may represent barriers and facilitators related to non-drug therapy access and motivation for use, such as awareness of therapies, beliefs about effectiveness, and other factors at the health system, provider, and patient levels.49,50 Future qualitative and mixed-methods work focusing on patterns of non-drug therapy use and referral can help clarify what drives non-drug therapy use.

Our overall finding of high levels of non-drug therapy use may be a promising sign that many veterans on LTOT for chronic pain are willing to engage with non-opioid therapies. The most commonly used therapies, including exercise/movement and psychological/behavioral therapies, are relatively effective and low-cost, with potential health benefits beyond pain management that may motivate patients’ use. Our findings suggest an opportunity for health care systems to encourage and support existing interest in non-drug therapy use by people on LTOT for chronic pain.

This study has limitations. First, self-report data are subject to recall bias and misclassification. Self-report nevertheless remains the most accurate and relevant form of assessment for non-drug therapy use, as administrative data omits use of therapies sought outside the medical system or not subject to billing.41,51 For example, a national survey of over 3,000 VA patients found that while 52% reported use of a CIH therapy in the past year, little of this care was obtained at VA.51 Results should be considered in the context of the broader literature. Second, administrative data are also subject to misclassification, particularly with respect to mental health diagnoses.52 Third, survey and administrative data indicators were necessarily limited in scope, and factors that we did not measure or analyze may be relevant to non-drug therapy use. Fourth, findings in this current analysis are cross-sectional and cannot consider temporality or causality. This cohort study of veterans on LTOT for chronic pain is ongoing and future analyses can explore non-drug therapy use in relation to pain and quality of life outcomes over time.

In conclusion, our study found that U.S. VA patients on LTOT for chronic pain commonly use non-drug therapies to manage pain, that observed non-drug therapy use classes reflect clinically relevant functional groups, and that patient characteristics are associated with use of different non-drug therapies. Further exploration of factors affecting non-drug therapy access and use for specific subpopulations, such as use of exercise/movement therapy by people with high pain interference, may enable implementation of non-drug and CIH therapy for chronic pain and expand safe, effective pain treatment options for people prescribed long-term opioid therapy.

Acknowledgments:

We thank the veteran participants in the study and the members of the research team, including Sean Nugent BA and Indulis Rutks BS.

Funding Source: The research reported here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (IIR 14–295). The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Preliminary data were presented as poster abstracts at the 2019 Minneapolis VA Health Care System Research Day (Minneapolis, MN, May 1 2019), the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Society of General Internal Medicine (Washington, DC, May 8–11 2019), and the 2019 Annual Meeting of the Society for Epidemiologic Research (Minneapolis, MN, June 18–21 2019).

References

- 1.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: A systematic review for a national institutes of health pathways to prevention workshop. Ann Intern Med 2015;162(4):276–286. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohnert AS, Valenstein M, Bair MJ, et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1315–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paulozzi LJ, Zhang K, Jones CM, Mack KA. Risk of adverse health outcomes with increasing duration and regularity of opioid therapy. J Am Board Fam Med 2014;27(3):329–338. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2014.03.130290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krebs EE, Gravely A, Nugent S, et al. Effect of Opioid vs Nonopioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain: The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2018;319(9):872–882. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong JJ, Côté P, Sutton DA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: a systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration. Eur J Pain. 2016:1–16. doi: 10.1002/ejp.931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Int Med 2007;147(July):478–491. doi:147/7/478 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Mclean RM, Forciea MA, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med 2017;166:514–530. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reid MC, Ong AD, Henderson CR, et al. Why We Need Nonpharmacologic Approaches to Manage Chronic Low Back Pain in Older Adults. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(3):338. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.8348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reid MC, Eccleston C, Pillemer K. Management of chronic pain in older adults. BMJ. 2015;350(8):h532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Foster NE, Anema JR, Cherkin D, et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2368–2383. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30489-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.VA/DoD Opioid Therapy Guideline Working Group. VA / DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. 2017.

- 12.Finestone HM, Juurlink DN, Power B, Gomes T, Pimlott N. Opioid prescribing is a surrogate for inadequate pain management resources. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62(6):465–468. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27302997%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4907548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahin RL, Boineau R, Khalsa PS, Stussman BJ, Weber WJ. Evidence-Based Evaluation of Complementary Health Approaches for Pain Management in the United States. Mayo Clin Proc 2016;91(9):1292–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic Therapies for Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med 2017;166(7):493. doi: 10.7326/M16-2459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elwy AR, Johnston JM, Bormann JE, Hull A, Taylor SL. A systematic scoping review of complementary and alternative medicine mind and body practices to improve the health of veterans and military personnel. Med Care 2014;52(12):S70–S82. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kligler B, Bair MJ, Banerjea R, et al. Clinical Policy Recommendations from the VHA State-of-the-Art Conference on Non-Pharmacological Approaches to Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. J Gen Intern Med 2018;Published. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4323-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? 2016. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health.

- 18.Ananth S. 2010 Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals. Alexandria, VA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ezeji-okoye SC, Kotar TM, Smeeding SJ, Durfee JM. State of care: complementary and alternative medicine in Veterans Health Administration – 2011 survey results. Fed Pr 2013;30:14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kligler B, Niemtzow RC, Drake DF, et al. The Current State of Integrative Medicine Within the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Acupunct 2018;30(5):230–234. doi: 10.1089/acu.2018.29087-rtl [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krebs EE, Clothier B, Nugent S, et al. Design, survey response, and baseline characteristics of the Evaluating Prescription Opioid Changes in Veterans (EPOCH) prospective cohort study. Under Rev 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Donaldson MT, Polusny MA, MacLehose RF, et al. Patterns of conventional and complementary non-pharmacological health practice use by US military veterans: A cross-sectional latent class analysis. BMC Complement Altern Med 2018;18(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2313-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Use of Complementary Health Approaches in the U.S.: National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). https://nccih.nih.gov/research/statistics/NHIS/2012/key-findings. Published 2017. Accessed April 7, 2018.

- 24.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleeland C. The Brief Pain Inventory User Guide. Houston, TX: University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center; 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Center for Health Statistics. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd9cm.htm Accessed April 6, 2018.

- 27.National Center for Health Statistics. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/icd/icd10cm.htm#FY 2018. release of ICD-10-CM Accessed April 6, 2018.

- 28.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Center for Injury Prevention and. CDC compilation of benzodiazepines, muscle relaxants, stimulants, zolpidem, and opioid analgesics with oral morphine milligram equivalent conversion factors, 2018 version.

- 30.Bohnert ASB, Ilgen MA, Galea S, McCarthy JF, Blow FC. Accidental Poisoning Mortality Among Patients in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. Med Care 2011;49(4):393–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunn KM, Saunders KW, Rutter CM, et al. Overdose and prescribed opioids: Associations among chronic non-cancer pain patients. Ann Intern Med 2010;152(2):85–92. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-0000620083827 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ilgen MA, Bohnert ASB, Ganoczy D, Bair MJ, Mccarthy JF, Blow FC. Opioid dose and risk of suicide. Pain. 2016;157(5):1079–1084. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller CJ, Maclehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: Different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):962–970. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: Applications in the Social Behavioral, and Health Sciences. Hoboken NJ: Wiley. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley InterScience; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Masyn KE. Latent class analysis and finite mixture modeling In: Little TD, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Quantitative Methods, Volume 2: Statistical Analysis. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2013:551–611. [Google Scholar]

- 36.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. 2017.

- 37.Lozier CC, Nugent SM, Smith NX, et al. Correlates of Use and Perceived Effectiveness of Non-pharmacologic Strategies for Chronic Pain Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioid Therapy. J Gen Intern Med 2018;33:46–53. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4325-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming S, Rabago DP, Mundt MP, Fleming MF. CAM therapies among primary care patients using opioid therapy for chronic pain. BMC Complement Altern Med 2007;7:1–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taylor SL, Herman PM, Marshall NJ, et al. Use of Complementary and Integrated Health: A Retrospective Analysis of U.S. Veterans with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain Nationally. J Altern Complement Med 2019;25(1):32–39. doi: 10.1089/acm.2018.0276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans EA, Herman PM, Washington DL, et al. Gender Differences in Use of Complementary and Integrative Health by U.S. Military Veterans with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Women’s Heal Issues. 2018;28(5):379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2018.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Healthcare Analysis & Information Group (HAIG), Department of Veterans Affairs Veterans Health Administration. FY 2015 VHA Complementary and Integrative Health (CIH) Services (Formerly CAM); 2015.

- 42.Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2001;135(4):262–268. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-4-200108210-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saper RB, Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Culpepper L, Phillips RS. Prevalence and patterns of adult yoga use in the United States: Results of a national survey. Altern Ther Health Med 2004;10(2):44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tindle HA, Wolsko P, Davis RB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP. Factors associated with the use of mind body therapies among United States adults with musculoskeletal pain. Complement Ther Med 2005;13(3):155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor SL, Giannitrapani KF, Yuan A, Marshall N. What Patients and Providers Want to Know about Complementary and Integrative Health Therapies. J Altern Complement Med 2018;24(1):85–89. doi: 10.1089/acm.2017.0074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hurst S, Maiya M, Casteel D, et al. Yoga therapy for military personnel and veterans: Qualitative perspectives of yoga students and instructors. Complement Ther Med 2018;40(October 2017):222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donaldson MT, Polusny MA, Maclehose RF, et al. The Pain Management Inventory: Patterns of conventional and complementary non-pharmacological therapy use in pain. In preparation.

- 48.Shiri R, Falah-Hassani K. Does leisure time physical activity protect against low back pain? Systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 prospective cohort studies. Br J Sports Med 2017;51(19):1410–1418. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bair MJ, Matthias MS, Nyland KA, Huffman MA, Stubbs DL, Kroenke K. Barriers and Facilitators to Chronic Pain Self-Management: A Qualitative Study of Primary Care Patients with Comorbid Musculoskeletal Pain and Depression. Pain Med 2009;10(7):1280–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00707.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker WC, Dorflinger L, Edmond SN, Islam L, Heapy AA, Fraenkel L. Barriers and facilitators to use of non-pharmacological treatments in chronic pain. BMC Fam Pract 2017;18:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12875-017-0608-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taylor SL, Hoggatt KJ, Kligler B. Complementary and Integrated Health Approaches: What Do Veterans Use and Want. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34(7):1192–1199. doi: 10.1007/s11606-019-04862-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Davis KAS, Sudlow CLM, Hotopf M. Can mental health diagnoses in administrative data be used for research? A systematic review of the accuracy of routinely collected diagnoses. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0963-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]