Abstract

The manuscript “Covid-19 And Vit-D: Disease Mortality Negatively Correlates with Sunlight Exposure” held our attention as we found fatal shortcomings that invalidates the analyses and conclusions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Vitamine D, Bias, Scientific integrity, Reproducibility

The manuscript “Covid-19 And Vit-D: Disease Mortality Negatively Correlates with Sunlight Exposure” (Lansiaux et al., 2020) held our attention as we found fatal shortcomings that invalidates the analyses and conclusions.

1. General considerations

First, the title itself is misleading as the manuscript does not report any information on Vitamin D since it was not measured in the context of this study.

Second it relies on unfounded hypotheses as the authors refer to a website (Prevenzione Tumori, 2020) without any scientific validity rather than to peer-reviewed articles.

Third, the reporting is poor. The manuscript does not conform to any reporting guidelines such as STROBE (von Elm et al., 2007). The public data sources citations that were provided in the paper are hyperlinks to main pages of websites, insufficient to find the actual data, hampering any reproducibility effort. From authors’ words, it is not clear whether “mortality rate” refer to the number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths divided by the number of inhabitants of each region (i.e. incidence of lethal COVID-19) or to the number of confirmed COVID-19 deaths divided by the number of COVID-19 confirmed cases (i.e. lethality of confirmed COVID-19). The former would be related to the incidence of COVID-19 while the latter is related to the prognosis of COVID-19. Trying to reproduce the results from Table 1 , we eventually found that the “mortality rate” refer to the latter and so, is related to the prognosis of COVID-19.

Table 1.

Updated data gathered (Santé publique France, 2020) for COVID-19 data, (Météo France 2020) for sunlight exposure (Yearly regional climate → Reporting of each station in each region), and (Ined 2020) for number of male and female inhabitants in 2019.

| Region | Name | Sunlight (h/year) by station | Average sunlight (h/year) | Cumulative discharge on 04/25/2020 | Cumulative inhospital deaths on 04/25/2020 | Hospitalized on 04/25/2020 | In-hospital mortality rate | Physician density (/100 000) | N male inhabitants | M female inhabitants | Sex ratio M/F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Île-de-France | 1637,3; 1661,6; 1752,5 | 1683,8 | 15754 | 5516 | 11609 | 0,168 | 396 | 5902798 | 6342009 | 0,931 |

| 24 | Centre-Val de Loire | 1758; 1767,3; 1833,3; 1743,6; 1811,4; 1840,6 | 1792,4 | 1056 | 348 | 974 | 0,146 | 265 | 1242428 | 1322830 | 0,939 |

| 27 | Bourgogne-Franche-Comté | 1774; 1767,7; 1848,8; 1836,4; 1799,3 | 1805,2 | 2227 | 786 | 1216 | 0,186 | 297 | 1358835 | 1434498 | 0,947 |

| 28 | Normandie | 1691,2; 1689,5; 1684,4; 1557,5 | 1655,7 | 974 | 314 | 615 | 0,165 | 288 | 1600250 | 1713090 | 0,934 |

| 32 | Hauts-de-France | 1617,5; 1679,7; 1659,9; 1669,4 | 1656,6 | 3672 | 1281 | 2385 | 0,175 | 302 | 2897369 | 3080068 | 0,941 |

| 44 | Grand Est | 1515,9; 1640,4; 1726,9; 1664,9; 1816,4; 1702,8; 1692,7; 1799; 1783 | 1704,7 | 7232 | 2714 | 4253 | 0,191 | 321 | 2692457 | 2832834 | 0,950 |

| 52 | Pays de la Loire | 1771,8; 1798,5; 1791,3; 1852 | 1803,4 | 1113 | 307 | 717 | 0,144 | 289 | 1843001 | 1944399 | 0,948 |

| 53 | Bretagne | 1529,8; 1564,6; 1717,1; 1827,2; 1683,8 | 1664,5 | 766 | 202 | 412 | 0,146 | 321 | 1618845 | 1714875 | 0,944 |

| 75 | Nouvelle-Aquitaine | 1888,8; 1995,9; 1899,8; 2007,6; 2035,4; 1982,4 | 1968,3 | 1276 | 289 | 707 | 0,127 | 337 | 2880996 | 3105322 | 0,928 |

| 76 | Occitanie | 2078,9; 2066,1; 2662,9; 1928,6; 1951,2; 1936,3; 2119,3; 2464,9 | 2151,0 | 2006 | 361 | 724 | 0,117 | 356 | 2847749 | 3051460 | 0,933 |

| 84 | Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes | 1861,7+1913+1985,1+1909,6+2404,8+2117,5 | 2032,0 | 4643 | 1212 | 2682 | 0,142 | 340 | 3890241 | 4115641 | 0,945 |

| 93 | Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur | 2510,9; 2775,4; 2724,2; 2744,2 | 2688,7 | 3366 | 625 | 1671 | 0,110 | 408 | 2413218 | 2635187 | 0,916 |

| 94 | Corse | 2579,3; 2755,8 | 2667,6 | 172 | 50 | 64 | 0,175 | 306 | 165666 | 175888 | 0,942 |

2. Major statistical flaws

The authors claimed that they analyzed data of 64,553,275 French citizens to explore the correlation between Sunlight exposure and Mortality. The main finding is a correlation between mortality rate and Sunlight exposure (that is considered as a surrogate marker of Vit-D) with an impressive “p-value of 1.532 × 10–32) correlated to the COVID-19 mortality rate, with a Pearson coefficient of -0.636”.

To explore this correlation, authors used a “Pearson correlation” (that explores association between two quantitative variables), and refer to aggregate data reported by various health agencies and institutions, i.e. Santé Publique France, INSEE, Meteo France). Upon request, the primary author shared on social media (Lansiaux, 2020) the scatterplot (not published in the manuscript) displaying the correlation they studied, suggesting an ecological analysis on data aggregated at regional level, confirmed by our further analysis (see below). Indeed, there are only 12 points in the figure, corresponding to the 12 regional areas reported in Table 1. Exploring such a correlation leads to weak evidence as it is prone to ecological fallacy, a bias that refers to inappropriate conclusions at an individual scale based on the analysis of aggregate data.

Moreover, a careful look at the manuscript, shows that the analysis done by the authors is totally flawed. From aggregate regional data provided in Table 1, we found that all correlation coefficients have been computed with 12 data points – one for each region – but that the statistical test has been performed as if there were as many data points as individuals (n=64,553,275). Indeed, the usual Student's t statistic associated to a Pearson's correlation coefficient is t=r × √[(n-2)/(1-r2)]. For n=64,553,275 and r=0.663, one can easily compute that t=7115.601 as is displayed on the first line of Table 3 for correlation between male sex and COVID-19 mortality rate.

Performing such an analysis violates the logic of Pearson's correlation. Indeed, Pearson's correlation is based on the empirical variance observed between the twelve data points that were given. The reduction of variance due to large regional sample sizes is already taken in account in this empirical variance and the Student's t statistic must be based on the sample size that has been used for the empirical variance calculation (i.e. n=12). This first error makes the estimation of statistical error highly biased. The actual error is at least √((64553275-2)/(12-2)) higher, i.e. 2540.7 times higher. After correction of this error, from Table 1 data, the significance level is P=0.03. Moreover, this statistic is based on two other dubious or erroneous assumptions. The first error is assumption of binormal distribution; to avoid this assumption, Spearman's correlation would be better than Pearson's correlation (P=0.04). The second assumption is that the 12 data points are independent. This second assumption is erroneous at least for sunlight exposure, since two neighboring regions have more similar climates than two distant regions. Consequently, even the P-value of Spearman's correlation is erroneous and the actual unbiased P-value would be higher if spatial correlation is taken in account!

Furthermore, we are surprised that all regions of metropolitan France were included but Corsica (Corse in French). Authors state that they excluded Corsica “because of poorer access there than on the continent", a statement made without any reference. In contrast, the Insee statistics indicate that the density of healthcare providers per inhabitants is in the same range as on the continent (Insee, 2020). As the authors point in the manuscript, they worked from a protocol. A time stamped protocol (e.g. registered on the Open Science Framework before any data extraction and analysis) is warranted to demonstrate that exclusion of Corsica was an a priori choice.

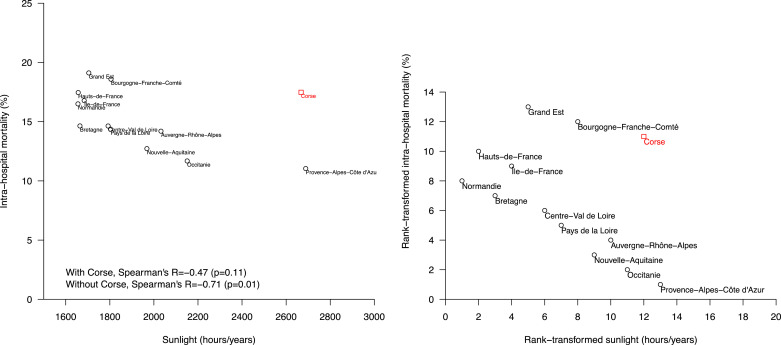

Indeed, an analysis based on Spearman correlation updated with data from Santé Publique France (Data from April 25th, 2020, extracted on July 24th, 2020 (Santé publique France, 2020)) and Méteo France extracted on July the 24th 2020 (Météo France, 2020), show that the correlation observed between intra-hospital mortality (cumulative hospital deaths divided by cumulative hospital deaths plus cumulative discharged patients plus number of currently hospitalized patients) and Sunlight without Corsica is not significant anymore when Corsica is added. With our new data extraction, Spearman's R=−0.47 (p=0.11) with Corsica versus R=−0.71 (p=0.01) without Corsica (Fig. 1 and Table 1 that includes data gathered from (Santé publique France, 2020; Météo France, 2020; Ined, 2020)). Note that our data extraction provided slightly different figures than author's ones, as we could not found the exact same data sources. Therefore, exclusion of Corsica may influence the results. If author cannot prove that this choice was made a priori, this is suspect of p-Hacking.

Fig. 1.

Scatterplot and Spearman's correlations of intra-hospital mortality (number of COVID-19 deaths in hospital divided by number of COVID-19 hospitalizations) and Sunlight exposure (with and without Corsica). Data and code to reproduce this analysis are available on the Open Science Framework (osf.io/mjz35).

Authors’ specify that they had assessed confounding factors. Indeed, with their erroneous analyses, they found that many potential confounding factors have significant effects (see Table 3) on the mortality rate, but no statistical adjustment is performed to cancel effects of these factors. Moreover, climate confounding, such as temperature have not even been analyzed.

Let's now apply reductio ad absurdum. Applying the same methods as authors of this article, we can calculate the association between sunlight exposure and number of senior assisted living beds for 100000 inhabitants of more than 75 years. With authors’ raw data (Table 1 of their article) and statistical methods we find a Pearson's R=−0.693 a Student's t statistic equal to −7720.827 and a P-value inferior to 10−30. After fixing the Student's t calculation, we find a Student's t statistic equal to −3.039 and a P-value equal to 0.01. Using updated data, including Corsica, and Spearman's correlation gives a R=−0.69 and a P-value equal to 0.009. Therefore, this method provides better evidence for the fact that sunlight exposure makes people build nursing homes (maybe via increased serological vitamin D in stakeholders building nursing homes, influencing their minds) than for the fact that vitamin D improves the prognosis of COVID-19; indeed, it is robust to the inclusion of Corsica. Another explanation would be the fact that the climate is influenced by nursing homes.

3. Conclusion

For all these reasons the manuscript has no informative value at all concerning any association between “Covid-19 And Vit-D”. Therefore, we think that the article methods and conclusions are too flawed to have any value.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We declare no competing interests.

References

- Ined. Estimation de population au 1er janvier, par région, sexe et grande classe d'âge2020[cited 2020 24/07/2020]. Available from:https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/159/estim.pop.nreg.sexe.gca.1975.2020.fr.xls.

- Insee. Professionnels de santé au 1ᵉʳ janvier 2018. Comparaisons régionales et départementales. 2020. Available from:https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/2012677.

- Lansiaux É., Pébaÿ P.P., Picard J.-L., Son-Forget J. Covid-19 and Vit-D: disease mortality negatively correlates with sunlight exposure. Spatial and Spatio-temporal Epidemiology. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2020.100362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansiaux, E.2020. Available from:https://twitter.com/EdLansiaux/status/1286656426371317762/photo/1.

- Météo France. Climat France / Ensoleillement2020[cited 2020 24/07/2020]. Available from:http://www.meteofrance.com/climat/france.

- Prevenzione Tumori [cited2020July the 26]. Available from:https://www.prevenzionetumori.eu/vitamina-d-possibile-ruolo-preventivo-e-terapeutico-nella-gestione-della-pandemia-da-covid19/.

- Santé publique France. Données hospitalières relatives à l’épidémie de Covid-192020[cited 2020 24/07/2020]. Available from:https://www.data.gouv.fr/fr/datasets/donnees-hospitalieres-relatives-a-lepidemie-de-covid-19/.

- von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J., Gøtzsche P.C., Vandenbroucke J.P. The Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(07)61602-x. Epub 2007/12/08PubMed PMID: 18064739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]