Abstract

BMP signaling is involved in many aspects of metazoan development, with two of the most conserved functions being to pattern the dorsal-ventral axis and to specify neural versus epidermal fates. An active area of research within developmental biology asks how BMP signaling was modified over evolution to build disparate body plans. Animals belonging to the superclade Spiralia/Lophotrochozoa are excellent experimental subjects for studying the evolution of BMP signaling because a highly conserved, stereotyped early cleavage program precedes the emergence of distinct body plans. In this study we examine the role of BMP signaling in one representative, the slipper snail Crepidula fornicata. We find that mRNAs encoding BMP pathway components (including the BMP ligand decapentaplegic, and BMP antagonists chordin and noggin-like proteins) are not asymmetrically localized along the dorsal-ventral axis in the early embryo, as they are in other species. Furthermore, when BMP signaling is perturbed by adding ectopic recombinant BMP4 protein, or by treating embryos with the selective Activin receptor-like kinase-2 (ALK-2) inhibitor Dorsomorphin Homolog 1 (DMH1), we observe no obvious effects on dorsal-ventral patterning within the posterior (post-trochal) region of the embryo. Instead, we see effects on head development and the balance between neural and epidermal fates specifically within the anterior, pre-trochal tissue derived from the 1q1 lineage. Our experiments define a window of BMP signaling sensitivity that ends at approximately 44 to 48 hrs post fertilization, which occurs well after organizer activity has ended and the dorsal-ventral axis has been determined. When embryos were exposed to BMP4 protein during this window, we observed morphogenetic defects leading to the separation of the anterior, 1q lineage from the rest of the embryo. The 1q-derived organoid remained largely undifferentiated and was radialized, while the post-trochal portion of the embryo developed relatively normally and exhibited clear signs of dorsal-ventral patterning. When embryos were exposed to DMH1 during the same time interval, we observed defects in the head, including protrusion of the apical plate, enlarged cerebral ganglia and ectopic ocelli, but otherwise the larvae appeared normal. No defects in shell development were noted following DMH1 treatments. The varied roles of BMP signaling in the development of some other spiralians have recently been examined. We discuss our results in this context, and highlight the diversity of developmental mechanisms within spiral-cleaving animals.

Keywords: BMP, Dpp, neural development, dorsal-ventral patterning, embryonic organizer, Spiralia, Mollusca, Crepidula

1. Introduction

Bone Morphogenetic Proteins (BMPs) are a group of signaling molecules that belong to the Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) superfamily. These proteins were originally discovered for their ability to induce bone and cartilage formation (Urist et al., 1971; Wozney et al.,1988), but have come to be known as crucial signals that control a wide range of processes in development, morphogenesis, homeostasis, and regeneration, and are also mis-regulated in many cancers (Salazar et al., 2016; Herrera et al., 2017; Gomez-Puerto et al., 2019). The BMP pathway is ancient and highly conserved across the animal kingdom, and so the field of EvoDevo has asked how this pathway evolved to mediate so many diverse functions within metazoans. Here, we use the marine gastropod, Crepidula fornicata, as an experimental system to investigate the role of BMP signaling during molluscan development. While BMP signaling has been widely investigated in deuterostomes (Zinski et al., 2018), ecdysozoans (Hamaratoglu et al., 2014), and increasingly in early-branching organisms like cnidarians (Rentzsch and Technau, 2016), it has not been as well-studied in the largest branch of metazoans, the Spiralia (Lophotrochozoa, Giribet, 2008).

Spiralia is a clade of bilaterians constituting at least a dozen distinct body plans (Hejnol, 2010; Henry, 2014; Dunn et al., 2018). It includes familiar taxa such as molluscs, annelids, and platyhelminthes, as well as several lesser-known groups, such as entoprocts and gnathostomulids (Giribet, 2008; Laumer et al., 2019). From a comparative developmental biology perspective, one useful attribute of this clade is the fact that extant species of several phyla exhibit a highly stereotyped early developmental program called spiral cleavage (Giribet, 2008; Henry, 2014). During spiral cleavage, the first two divisions of the zygote establish four blastomeres, called A, B, C, D, which subsequently divide repeatedly. These cells typically give rise to 4 tiers or quartets (“q”) of cells called micromeres at the animal pole [including the first quartet (1a-1d; or “1q”), the second quartet (2a-2d; or “2q”), the third quartet (3a-3d; or “3q”), and the fourth quartet (4a-4d; or “4q”)], while their larger, vegetal sister cells are called macromeres, and are designated by correspondingly numbered capital letters (see Figure 1). The stereotyped cleavage pattern allows one to identify homologous cells by virtue of their birth order and position within the embryo. Furthermore, in multiple species detailed lineage tracing studies of individual micromeres and macromeres reveals that specific cells give rise to the same body parts (e.g., in many species the photoreceptors/ocelli come from 1a and 1c; trunk mesoderm comes from 4d, etc.), demonstrating that the cells’ fates are also homologous (Henry and Martindale, 1998; Henry, 2014). Within this highly conserved framework, variations between species have also been observed. For example, the ocelli in the larval chiton Chaetopleura apiculata arise from 2a and 2c instead of 1a and 1c (Henry et al., 2004), and trunk mesoderm in the polychaete Capitella teleta mainly comes from 3c and 3d instead of 4d (Meyer et al., 2010). Such variations provide an opportunity to link changes in the spiral cleavage program to diversification of morphology and signaling pathways at single-cell resolution.

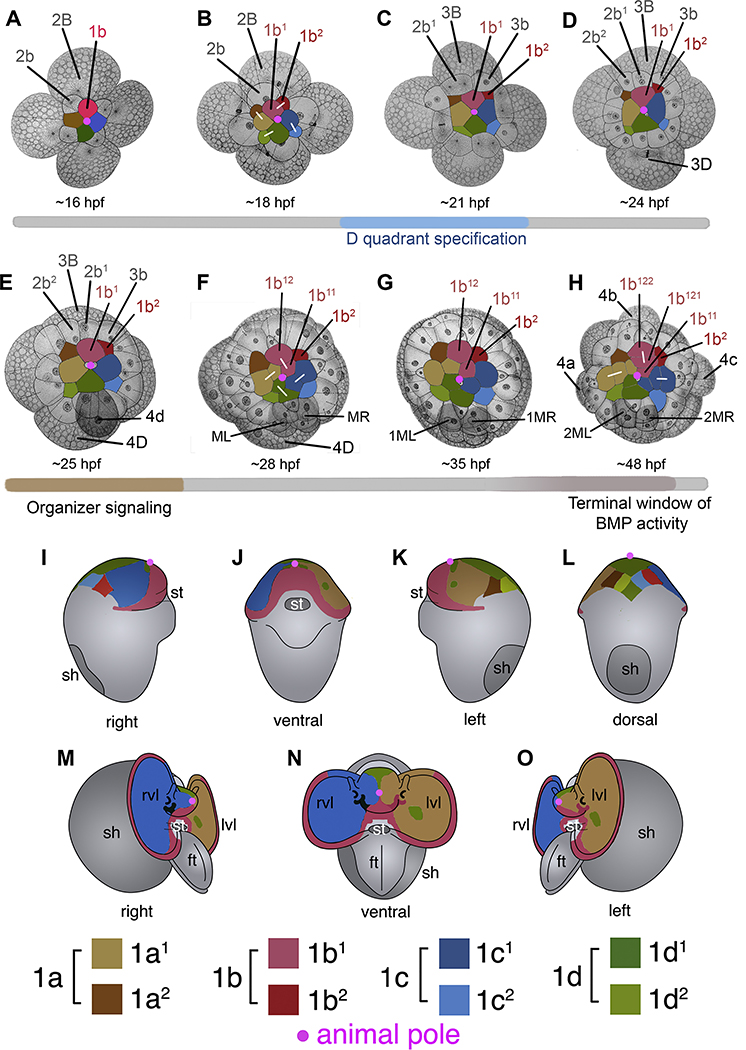

Figure 1.

Overview of early development focusing on the first quartet (1q). A-H. Animal pole views of cleavage-stage embryos, with the first quartet (1a-1d) and its descendants highlighted according to the color key. For reference and simplicity, the 1b clone is labeled, as well as other cells within the B quadrant. Selected cells within the D quadrant are also labeled. White bars indicate sister cells following recent cell divisions. The gray bar below the embryos indicates developmental time, and approximate time intervals marked in color indicate developmental events that correspond to those highlighted in Figure 9. The age (hours post fertilization; hpf) of the embryos are also shown. Drawings modified from Conklin (1897). I-O. Individual lineages are colored as in A-H. Views are indicated under each diagram. I-L. Summary diagrams showing behavior of the 1q2 micromeres and 1q1 clone in four different views of an organogenesis stage embryo (~190 hpf). Note at this stage the 1q2 cells occupy a small area on the dorsal surface of the head. M-O. Three views of an advanced veliger larva (~230 hpf) showing contributions to the formation of the head, anterior surface of the velum, and the prototroch by progeny of the 1q1 cells. By this stage the 1q2 cells have been lost from the embryo. ft, foot; lvl, left velar lobe; rvl, right velar lobe; sh, shell; st, stomodeum. Images modified from Lyons et al. (2015, 2017).

Since phyla that possess spiral cleavage are distributed widely across the Lophotrochozoa clade, parsimony suggests that the last common ancestor of this group exhibited spiral cleavage, and that spiral cleavage was subsequently lost in multiple lineages (e.g., brachiopods, phoronids, and cephalopods; Hejnol 2010). Thus, the spiral cleavage program is considered to be homologous between phyla, enabling one to study cell types, tissues, and organs in a phylogenetic context, independent of the genes that they express. This paradigm offers an unprecedented opportunity to ask how developmental signaling pathway members, like BMPs, have diversified during evolution. For example, BMP signaling has recently been shown to be necessary for the function of the organizer in the mud snail Tritia (Ilyanassa) obsoleta (Lambert et al., 2016), but not in the polychaete Capitella teleta (Lanza and Seaver, 2018; Corbet et al., 2018). Since we know that the cells that function as organizers in these two species are different (3D and 2d, respectively), we can ask how organizer specification and BMP signaling vary between species, independently of one another. These types of insights require investigations of developmental processes in a wider range of spiralians.

This study focuses on one of the best-studied spiralian species, the slipper snail C. fornicata (Henry et al., 2010a; Henry and Lyons, 2016; Lesoway and Henry, 2019). C. fornicata is a caenogastropod mollusc that is abundant in the waters around the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, where E.G. Conklin (1897) made his initial description of its early development at the end of the 19th century. More recently, we have developed this species for functional studies, including generating embryonic transcriptomes, describing the spatiotemporal expression patterns of regulatory genes (e.g. Henry et al., 2010b; Perry et al., 2015; Lorente-Sorolla et al., 2018; Osborne et al., 2018), investigating the role of signaling pathways such as MAPK and β-catenin (Henry and Perry, 2008; Henry et al., 2010c), preparing high resolution fate maps (Hejnol et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2012, Lyons et al., 2015; Lyons et al., 2017), and demonstrating the application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing within the Lophotrochozoa for the first time (Perry and Henry, 2015).

Here, we investigate the role of BMP signaling in C. fornicata development through in situ expression analysis of several pathway members and by treating embryos with ectopic recombinant BMP4 protein, and a BMP pathway pharmacological inhibitor, the selective Activin receptor-like kinase-2 (ALK-2) inhibitor Dorsomorphin Homolog 1 (DMH1). We find that applying BMP4 protein leads to morphogenetic defects, and interferes with anterior-neural development and dorsal-ventral patterning within the pre-trochal region, which is derived from the progeny of the first quartet micromeres. In contrast, patterning in the post-trochal region, which is derived from the 2q through 4q micromeres, and 4Q macromeres, was not severely affected. Treating embryos with DMH1 leads to abnormal development of the apical plate and an excess of anterior neural structures, such as ectopic ocelli, but does not prevent normal dorsal-ventral patterning in pre-trochal or post-trochal regions. These phenotypes were observed when BMP4 protein or DMH1 inhibitor were added anytime up until the birth of the 4a-4c micromeres (~44–48 hours post fertilization), including time points long after embryological experiments show that 4d organizer activity is completed (approximately 25–26 hours post fertilization, Henry et al., 2017). We also saw little to no effect on shell formation in the BMP inhibition experiments. Collectively, we did not observe defects that mimic or phenocopy loss of organizer activity in either of these treatments. Instead, BMP signaling appears to play a key role in regulating downstream events related to the reception of organizer signaling within the anterior progeny of the first quartet micromeres (more specifically the 1q1 cells). We discuss these results in the context of recent studies of BMP function in other spiralians. Our results lend further evidence to support the idea that embryonic patterning mechanisms vary significantly between spiralian species, despite their highly conserved cleavage program.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Animal care and handling

Adult Crepidula fornicata were obtained from the Marine Resources Center at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA. Embryos were obtained and reared as previously described (Henry et al., 2006, 2010a, 2010b). Embryos were kept between 20°C and 22°C and staging follows the timing and nomenclature described previously (Figure 1; Lyons et al., 2012, 2015, 2017).

2.2. Lineage tracing and mRNA injections

Previous studies established the fates of the major cell lineages, including neuronal/sensory fates (Hejnol et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2012; Lyons et al., 2015; Lyons et al., 2017). In this study, specific micromeres were pressure micro-injected with either Rhodamine Green dextran (cat. no. D-7153, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) or DiIC18 (cat. no. D-282, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) at the 8 to 25-cell stages, as previously described (Henry and Martindale, 1998; Henry et al., 2006; Hejnol et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2012, 2015, 2017). These embryos were treated with either BMP4, DMH1, or treated as negative controls (see below), and then raised to various time points for clonal analyses of the injected cells’ progeny. Embryos were photographed live following gentle compression under a coverslip using epifluorescence and confocal microscopes (see below). Five to ten embryos were examined for each set of labeled cells/clones. To help visualize the arrangement of cells in live cleavage-stage embryos, we microinjected zygotes with synthetic mRNAs to express various combinations of fluorescently tagged proteins, as described previously (Lyons et al., 2015). In those cases, we followed cell outlines using a GFP fusion of the actin-binding domain of utrophin (UTPH-GFP), and nuclei using a histone H2B-RFP fusion protein.

2.3. Sequence Analysis and Cloning BMP pathway components

Homologous invertebrate sequences were collected from publicly available databases (UniProtKB, NCBI) and used individually for tBlastn alignments against each of our available C. fornicata EST databases (Henry et al., 2010b; Perry et al., 2015), using the program Geneious (Auckland, New Zealand). Those C. fornicata ESTs that aligned well with the gene of interest were submitted to BlastX (NCBI) for verification. In cases where we obtained only partial sequences for the genes of interest, we attempted to lengthen the sequence by using the C. fornicata fragment as the query in a Blastn alignment targeted to the available C. fornicata databases (Henry et al., 2010b). Any extended sequence information was compiled as a contig and submitted to BlastX again for verification. With these methods we identified the following genes: Cfo-Dpp (accession number MN561846), Cfo-BMPRIb (accession number MN561847) Cfo-chordin (accession number MN561849) and Cfo-noggin-like (accession number MN561848). Cfo-Smurf2 and Cfo-Smad1/5 were described previously (Henry et al., 2010b, accession numbers HM040895, and HM040893, respectively), but analysis of their expression has been expanded here to include additional stages and is reported for the sake of comparison with the other BMP pathway genes.

2.4. Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference analyses

Protein coding sequences were aligned using ClustalW v2.1 (Larkin et al., 2007) with protein sequences from a previously conducted study (Kenny et al., 2015). Alignments were trimmed to remove poorly aligned positions from the matrix using Gblocks v0.19b (Talavera and Castresana, 2007), using an option to provide less strict flanking positions. Both Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference analyses were carried out to infer phylogenetic relationships (Figure 2). Maximum Likelihood analysis was performed with RAxML v8.2.12 (Stamatakis, 2014) with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Prior to running maximum likelihood analysis, the best model for protein evolution was chosen under the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) using ProtTest v2.4 (Abascal et al., 2011). Bayesian inference analysis was performed using MrBayes v3.2.7a (Ronquist et al., 2012), with four Markov chains run for 1,000,000 generations, with sampling taken every 1000 generations; the first 25% of trees were discarded as burn-in, and the remaining trees were used to generate the posterior probabilities.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of C. fornicata BMP pathway components. Phylogenies were reconstructed using Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference methods. The topology presented for all trees here is from the maximum likelihood method, with numerical values at nodes indicating bootstrap (of 1000 replicates) or posterior probability values. Crepidula fornicata sequences are highlighted in red. A. Phylogeny of BMP-ligands from an 88bp amino acid alignment and determined using the WAG model. B. Phylogeny of BMP receptors from a 91bp amino acid alignment and determined using the LG model. The tree was rooted with a Raf gene from D. melanogaster (X07181). C. Phylogeny of SMAD from a 126bp amino acid alignment. Protein evolution was determined using the LG model. D. Phylogeny of Chordin from a 125bp amino acid alignment. Protein evolution determined using the Dayhoff model, and BMP-binding endothelial regulator from H. sapiens (NP597725.1) used to root the tree. E. Phylogeny of Noggin from 79bp amino acid alignment. Protein evolution determined using the WAG model. F. Phylogeny of SMURF from a 175bp amino acid alignment. Protein phylogeny determined using the LG model. Wwp2 protein sequence from H. sapiens (AAC51325.1) was used to root the tree.

2.5. In situ hybridization

Genes of interest (expression shown in Figures 3–8) were cloned according to methods described previously (e.g., Perry et al., 2015; Osborne et al., 2018). Linearized template DNA was prepared for use in transcription reactions to generate DIG-labeled RNA. Each probe was prepared using either T7 or SP6 RNA polymerase (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and DIG-labeling mix (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Each probe was purified with the RNeasy MinElute Cleanup kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and quantified on a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). Following in situ hybridization, nuclei were labeled with 0.5ug/ml DAPI and specimens were mounted in 80% glycerin/20% 1X PBS and photographed with a Zeiss M2 Imager compound microscope equipped with an Axiocam 503 mono camera (Carl Zeiss Inc., Munich, Germany).

Figure 3.

Expression of Cfo-dpp during development in C. fornicata. A-BB. 8-cell to 200+ hpf (larval stages). Refer to detailed descriptions in the Results section. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image (an., animal; veg., vegetal; vent., ventral). DAPI staining shown in B, D, F, H, J, L, N corresponds to embryos in A, C, E, G, I, K, M, respectively. S-T, U-X, Y-BB show different views of three different embryos, respectively. Anterior is toward the top of the figure in M-BB. The animal pole is labeled with an asterisk. A-B. 8-cell embryo. C-D. 16-cell embryo. E-F. 24-cell embryo. G-H. 40 hpf embryo. I-J. 42 hpf embryo. K-L. 45 hpf embryo. M-N. 90 hpf embryo. O. 94 hpf embryo. P. 105 hpf embryo. Q. 120 hpf embryo. R. 137 hpf embryo. S-T. 170 hpf embryo. U-X. 180 hpf embryo. Y-BB. 200 hpf embryo. 4D and its progeny, 4d, are labeled in G-I, K. The teloblasts (progeny of the mesentoblast 4d), ML and MR are labeled in L. White arrowheads point to localized areas of expression in the neurogenic region of the anterior plate. bp, blastopore; ft, foot; in, intestine; sg, shell gland; sh, shell; st, stomodeum; vr, velar rudiment. Scale bar = 50 μm in BB.

Figure 8.

Expression of Cfo-smurf2 during development in C. fornicata. A-P. 2-cell to 130 hpf (late gastrulation). Refer to detailed descriptions in the Results section. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image (an., animal; veg., vegetal; vent., ventral). DAPI staining shown in B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P corresponds to embryos in A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, respectively. The animal pole is labeled with an asterisk. Anterior is toward the top of the figure in M-P. A-B. 2-cell embryo. C-D. 4-cell embryo. E-F. 8-cell embryo. G-H. 24-cell embryo. I-J. 45 hpf embryo with the 4D cell labeled, as well as its progeny, 4d. K-L. 60 hpf embryo with the 4D cell labeled. M-N. 94 hpf embryo. O-P. 130 hpf embryo. bp, blastopore. Scale bar = 50 μm in P.

2.6. Drug Treatments

Embryos were treated with either recombinant human BMP4 (Stemgent, Lexington, MA, Stemfactor BMP-4; cat. no. 03–0007) or the ALK-2 receptor inhibitor DMH1 (Tocris, Bristal, UK; cat. no. 4126) during specific stages of development, as indicated in Figure 9. BMP4 protein was made up as either a 40μg/ml or 50μg/ml stock in a 4mM HCl solution and stored at −80°C. The stock was then diluted into FSW. We compared the effects of treating embryos with different concentrations of BMP4. Embryos were treated at 100, 50, 40, 12.5, 6.25 and 2.25ng/ml for 24 or 48 hrs beginning either at early cleavage stages (2–4 cell stages) or at 34–38 hours post fertilization (hpf). 100% of those embryos (N = 1,213) exhibited the characteristic phenotypes described in the Results section. A lower range of concentrations was also tested (1.25ng/ml to 0.025ng/ml) and the percentage of cases exhibiting these phenotypes was found to decrease in a dose dependent fashion (1.25ng/ml = 89% (N=142); 0.63ng/ml = 67% (N=63); 0.31ng/ml = 52% (N=77); 0.13ng/ml = 21% (N=121); 0.025ng/ml = 2% (N=80)). The remaining embryos at those lower concentrations appeared to develop normally. For most experiments, unless noted, BMP4 was used at 40ng/ml, which ensured a robust response.

Figure 9.

Illustration showing the various time intervals for experimental BMP4 and DMH1 treatments. The two timelines at the top show particular stages of development (above) and hours past fertilization (hpf, below). Colored bars below represent corresponding windows for each set of drug treatments. Green bars indicate that characteristic phenotypes were observed, and red bars signify that only normal phenotypes where observed. Solid vs. dashed bars indicate some treatments extended over 24 or 48 hrs, respectively. At least 30 embryos were included in each treatment. Numbers associated with specific bars indicate the number of replicates performed using different batches of embryos, followed by the total number of embryos examined and the percent showing the defective phenotypes. The appearance of particular defective phenotypes (noted in green with quotation marks) is also included for the time they are first apparent. The blue horizontal bar represents the time window for D quadrant specification (as determined by Henry and Perry, 2008). The brown horizontal bar represents the time interval for 4d organizer signaling (see Henry et al., 2017). The graduated grey horizontal bar leads to the end of the window of BMP signaling activity, which corresponds with the birth of the 4th quartet micromeres, 4a, 4b and 4c. Over 4400 control embryos were raised for these different experiments. Nearly all of those embryos developed normally and exhibited none of characteristic BMP4 or DHM1 phenotypes.

DMH1 was made up as a 40mM stock in DMSO and stored at −20°C and freshly diluted into FSW. A range of concentrations was examined (from 80 to 5μM). DMH1 is not completely soluble in FSW and a fine precipitant was often observed at higher concentrations. Embryos were treated for 24–48 hrs beginning either at early cleavage stages (2–8 cell stages) or at 36hpf. All of these concentrations gave rise to the characteristic phenotypes described in the Results section; however, the percentage of cases exhibiting these phenotypes was found to be less at the lower concentrations (80μM = 43% (N=120); 40μM = 44% (N=525); 20μM = 28% (N=50); 10μM = 21% (N=104); 5μM = 4% (N=180)). The remaining embryos at those lower concentrations appeared to develop normally. For most experiments, unless noted, the embryos were treated with 40μM DMH1, which ensured a robust response.

Controls were treated with the equivalent dilution of either 4mM HCl or DMSO in FSW and these treatments were not found to affect normal development. Drug treatments were carried out in gelatin-coated 35mm petri dishes in a total volume of 3ml or 4ml FSW for either 24 or 48 hrs. Following treatment, the embryos were washed three times by serial transfer through dishes containing fresh FSW and raised further in FSW containing penicillin and streptomycin (Henry and Martindale, 1998; Hejnol et al., 2007). Extensive experiments varying the beginning and ending times of these treatments were conducted to establish the stages of development that are sensitive to these perturbations (Figure 9).

2.7. Fixation, Immunohistochemistry, and Microscopy

All specimens were fixed in a 3.7% solution of formaldehyde (Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) diluted in filtered sea water (FSW) for 1 hr at room temperature. For immunohistochemistry, the formaldehyde solution was removed immediately after fixation and replaced by three washes of 1X PBS (1X PBS:1.86mM NaH2PO4, 8.41mM Na2HPO4, 75mM NaCl, pH 7.4) followed by three 100% methanol washes. Samples were stored in 100% methanol at −80°C. In those cases used for phalloidin staining (see below), the dehydration steps in methanol were omitted and the samples were stored at 4°C in 1X PBS. Antibody localization was performed using anti-FMRFamide (1:100, catalog #20091; ImmunoStar Inc., Hudson, WI). The secondary antibody used was anti-mouse Alexafluor 488 (1:400, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) following the methods described in Giani et al., (2011) and Lyons et al., (2017). Specimens were visualized on a Zeiss Axioplan microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Munich, Germany) equipped with a Spot Flex camera (Spot Imaging Solutions, Sterling Heights, Michigan). Some images were captured using a Zeiss M2 Imager compound microscope equipped with an Axiocam 503 mono camera (Carl Zeiss Inc., Munich, Germany). Multifocal stacks of brightfield images were combined and flattened using Helicon Focus stacking software (Helicon Soft Ltd., Kharkov, Ukraine). In situ hybridization was also used to examine the expression of Cfo-Six3 (accession number KP885705), as an early neural marker (Perry et al., 2015), following the methods described in section 2.5, above.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Crepidula development

The early cleavage pattern, cell lineage nomenclature, and morphogenesis of the C. fornicata embryo has been described previously (Conklin, 1897; Henry et al., 2006; Henry and Perry, 2008; Hejnol et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2012; 2015; 2017). Here, we briefly highlight the birth, arrangement, and ultimate cell fates (Figure 1) of key blastomeres leading up to and following the BMP signaling window described below. When embryos are raised at ~20°C, the first quartet of micromeres is born at the eight-cell stage, approximately 12–13 hpf. Earlier cleavages occur at approximately 7 hpf (two-cell stage), 10 hpf (four-cell stage), and 13 hpf (eight-cell stage). By 16 hpf, the embryo has reached the 12-cell stage with the primary quartet (1a-1d=1q) located at the very center of the animal pole, and the secondary quartet (2a-2d=2q) located more centrifugal and vegetal to the first quartet cells (Figure 1A). Note that each 1q cell undergoes an asymmetric division, resulting in a larger, more animal-situated 1q1 cell, and a smaller, more vegetal-situated 1q2 cell (Figure 1B). Over the next 3 hrs the 1q and 2q cells continue to divide, and the third quartet of micromeres is born at the 20-cell stage (by 20 hpf, 3a-3d=3q) (Figure 1C).

Until the 24-cell stage (which is reached at approximately 21–22 hpf), the arrangement of cells around the animal-vegetal axis is symmetric, and experimental manipulations show that the dorsal-ventral (D-V) axis is not yet fully determined (Henry et al., 2006; Henry and Perry, 2008; Henry et al., 2017a). Earlier, during the 20-cell stage, direct cell contacts involving the 1q1 derivatives of the first quartet and the 3Q macromeres result in the determination of the dorsal, D quadrant cell, 3D (Henry and Perry, 2008; Henry et al., 2017a). Then, during the 24-cell stage, the first obvious asymmetry emerges when the 3D macromere protrudes from the embryo, as it prepares for mitosis (Figure 1D). Around 24–25 hpf, 3D completes its precocious division (relative to the other 3rd quartet macromers, 3A-3C) and gives rise to the 4d micromere and the 4Q macromere (Figure 1E). This 25-cell stage embryo has characteristic asymmetries: a pronounced protrusion of the 4D macromere and the presence of the large 4d micromere (Figure 1E). These asymmetries are very easy to score with the dissecting microscope and serve as obvious visual assays for assessing cell quadrant asymmetries and the D-V axis in the early embryo.

The 4d micromere is the embryonic organizer in C. fornicata (Henry et al 2006; Henry and Perry 2008). Systematic ablation studies demonstrated that during the first hour of its birth the 4d cell signals to the cells in the micromere cap to pattern certain fates along the D-V axis in the pretrochal and post-trochal territories (Henry et al., 2017a; Figure 1E). If 4d is removed during the first hour after its birth, the resulting embryos exhibit abnormal radialized forms of development, with no specific pre-trochal structures, such as the ocelli (derived from the 1c1 and 1a1 cells), and no specific post-trochal structures, such as the shell (derived from 2a-2d). These embryological experiments establish the timing and function of the organizer and form a framework for comparison with the present BMP perturbation treatments. If BMP signaling is mediating the signal emanating from the 4d organizer during the first hour following its birth, we predict that perturbing BMP signaling during this same period would phenocopy the removal of the 4d cell (i.e. loss of eyes and shell).

During organizer signaling and subsequent stages of development, the micromere cap cells continue to divide and expand over the macromeres (Figure 1E–H). Note that the 1q2 cells do not divide (i.e., are cleavage arrested), but flatten out and ultimately re-arrange to form part of a temporary ciliated epithelium located on the dorsal side of the head (Figure 1I–L). Following organizer signaling, the 4d cell undergoes a symmetric, bilateral division, giving rise to the teloblasts, ML and MR, around 27–28 hpf (Figure 1F). Both ML and MR divide at ~32 hpf to give rise to their first set of progeny, the endodermal cells 1mR and 1mL, and the teloblasts are renamed 1ML and 1MR (Figure 1G). The teloblasts continue to divide, giving rise to stereotyped clones of cells whose division patterns and fates have been documented in detail (Lyons et al., 2012; Figure 1G–H). At ~48 hpf the embryo reaches a characteristic “morula” stage during which the 3A-3C macromeres divide to give rise to the remaining 4th quartet micromeres (which become endodermal cells, 4a-4c) (Figure 1H). At that stage there are six progeny within the 4d sub-lineage, including the teloblasts 2ML and 2MR (Figure 1H; Lyons et al., 2012). The stereotyped division of the 4d lineage is another feature that we use to carefully monitor the stage of the embryos and to check for phenotypes following drug treatments.

Gastrulation and organogenesis proceed over the next several days and by ~196 hpf the pre-veliger stage is reached (Figure 11–L), and by ~230 hpf the veliger stage is reached (Figure 1M–O). Detailed lineage tracing studies (Hejnol et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2017) show that the head, neural, and velar tissues are made up largely of the 1q1 cells’ progeny, while the four cleavage arrested 1q2 cells are ultimately lost from the larva. The 2q and 3q lineages contribute to ectodermal and mesodermal cells, including cells of the stomodeum/esophagus, post-trochal region, muscles within the velum, and the shell gland (Hejnol et al., 2007; Henry et al., 2007; Lyons et al., 2015). The 4d cell gives rise to the intestine, heart, muscles (such as the main retractor muscle), cells of the larval kidney complex, and the primordial germ cells (Lyons et al., 2012). The well-understood cleavage pattern, experimental embryology experiments, and fate map of the early Crepidula embryo were used to interpret gene expression patterns, and the drug treatment experiments described below.

Figure 11.

Development of BMP4 protein and DMH1 treated embryos in which one 1q micromere had been injected with Dil at the 8-cell stage. Injected micromeres are indicated in the lower right corner of each image. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image. The animal pole is located towards the top of the figures and marked with an asterisk. A. Control embryo (~115 hpf). B. Sibling embryo to that show in A, treated with BMP4 for 48 hrs beginning at the 8-cell stage. The 1 c clone of labeled cells is similar to that of the control embryo; however, the more prolific clone of 1c1 progeny are somewhat condensed. C. BMP4-treated embryo (~122 hpf), beginning to undergo constriction (white arrowheads). BMP4 treatment began at the 8-cell stage and continued for 48 hrs. The labeled clone of the 1a micromere extends just to the point of constriction. Note the presence of the blastopore/stomodeum in the vegetal portion. D. An even older BMP4 treated embryo (~168 hpf), which has undergone constriction (white arrowheads). The labeled clone from the 1d micromere extends just to the point of constriction. The animal fragment has not yet undergone complete separation. E. BMP4-treated embryo (~140 hpf) stained with DAPI and undergoing constriction. Treatment began at 24 hpf and continued for 24 hours. The blastopore is still located towards the vegetal pole. A region of highly condensed ciliated cells around the blastopore/stomodeum are intensely labeled. F. Corresponding untreated control embryo to that shown in E. Note the ventral location of the blastopore/stomodeum, which has become displaced towards the anterior pole. G. Control embryo (~115 hpf), in which the 1d micromere had been injected with Dil at the 8-cell stage. Large flattened cells that contribute to the temporary ciliated epithelium are labeled (1d2, 1d121 and 1d122). H. Sibling embryo (~115 hpf) in which the 1d micromere had been injected with Dil at the 8-cell stage, and that was treated with DMH1 beginning at the 8-cell stage for 48 hrs. A fairly normal appearing 1d clone is seen. I. Another older embryo (~130 hpf) that was treated with DMH1 beginning at 24 hpf for 24 hrs. Normal appearing 1d clone is seen. J-O. Combined DIC and fluorescence micrographs showing development of the 4d lineage (green fluorescent dextran) within control, BMP4 and DMH1 treated embryos. J. Control untreated embryo (~168 hpf). Note labeled intestine, larval kidney and scattered mesenchyme cells derived from 4d. K. Lateral view of BMP4 treated embryo (~122 hpf). Embryo was treated beginning at ~26 hpf for 24 hrs. This embryo is beginning to undergo constriction (white arrowheads). Though not completely normal, note the presence of bilateral paired mesodermal bands derived from 4d, as well as the central intestinal rudiment. The terminal large cells that will form the larval kidney complex are also present. L. BMP4 treated embryo (~168 hpf). Embryo was treated beginning at 54 hpf for 48 hrs. It has developed normally and does not exhibit the phenotype of embryos subjected to earlier treatments (compare with D). M. DMH1 treated embryo (~144 hpf). This is the same embryo shown as a DIC only image in Figure 11J. This embryo was treated beginning at the 4-cell stage for 48 hrs. Note presence of bilateral paired mesodermal bands and intestinal rudiment derived from 4d. N. DMH1 treated embryo (~168 hpf). Treatment began at ~26 hpf and continued for 24 hrs. Note the presence of a prominent anterior protrusion from the head. The 4d lineage appears to be developing fairly normally, except the development of the intestinal rudiment appears to be delayed. O. DMH1 treated embryo (~168 hpf). This embryo was treated beginning at ~54 hpf for 48 hrs. This embryo is developing normally and does not exhibit the phenotype of embryos subjected to earlier treatments (compare with N). ft, foot; in, intestine; kc, larval kidney; pr, anterior protrusion; sh, shell; st, stomodeum. Scale bar in O = 50 μm.

3.2. Phylogenetic analysis of BMP pathway components

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) ligands are part of the TGF-β superfamily (Wozney et al., 1988), and are classified into four subgroups: (1) BMP 2 and 4; (2) BMP 5, 6, 7, and 8; (3) BMP 9 and 10; (4) BMP 12, 13, and 14 (Burt and Law, 1994; Wang et al., 2014; Ongaro et al., 2019). Results for both Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference analyses of the phylogenetic relationship of the TGF- β/BMP superfamily resulted in the recovery of four distinct clades of BMP-ligand subgroups. Within the BMP 2/4 clade, there is support for a Dpp clade (Figure 2A). The Crepidula fornicata Dpp homolog (accession number MN561846) was found to be sister to two molluscan Dpp homologs (L. gigantea 205842; P. vulgata AF440097). Further, Dpp homologs from A. mellifera and D. melanogasterwere sister to the molluscan Dpp clade.

BMP-ligands bind to two heteromeric receptor complexes of transmembrane, serine/threonine kinase receptors: type I receptor (BMPR1) and type II receptor (BMPR2) (Sieber et al., 2009; ten Dijke and Hill, 2004). We performed a protein phylogeny for BMP receptors using 14 BMP receptor genes from various metazoan organisms including: seven BMPR2 and seven BMPR1 sequences from metazoan species. BMP receptor type 1 and type 2 clades were recovered in both Maximum Likelihood and Bayesian Inference phylogenies (Figure 2B), which is in agreement with the two types of BMP receptors that have been previously identified (Sieber et al., 2009; ten Dijke and Hill, 2004). Further, two BMP receptors were found for C. fornicata from developmental transcriptomes: BMP type 1 receptor (BMPR1, accession number MN561847) and BMP type 2 receptor (BMPR2, accession number MT025178). Both phylogenetic analyses showed that these two sequences fell within their respective type 1 and 2 clades.

Three evolutionarily conserved SMAD subfamilies are recognized (Newfeld and Wisotzkey, 2006): (1) R-SMADS (SMAD1, 2, 3, 5, 8/9); (2) I-SMADS (SMAD6, 7); and (3) Co-SMAD (SMAD 4). The SMAD protein phylogeny conducted in this study included 46 metazoan sequences for SMAD; the topology of the tree was in agreement with the three SMAD subtypes that have previously been identified. C. fornicata SMAD1/5 fell within the SMAD1/5/8 clade of R-SMADS and was grouped within a molluscan clade of SMAD1/5/8 (Figure 2C, accession number HM040893).

Chordins are known for being BMP2/4 (Dpp) antagonists (Abreu et al., 2002; Blader et al., 1997), and are typified by highly conserved cysteine-rich (CR) repeats. Further, chordin and closely related chordin-like genes have been found across the Metazoa (Dubuc et al., 2019). Both Maximum likelihood and Bayesian Inference analyses of 15 chordin and chordin-like genes from various metazoan organisms revealed congruent topologies for chordin and chordin-like clades (Figure 2D). Crepidula fornicata chordin (accession number MN561849) fell within the chordin clade, and was closely related to two other molluscan chordins.

Noggins are BMP antagonists that have been phylogenetically classified into two clades: canonical noggin and noggin-like (Molina et al., 2011). Noggin-like proteins contain a 50–60 amino acid insertion between the 5th and 6th cysteine residue, which are absent in noggin proteins (Molina et al., 2009). A maximum likelihood protein phylogeny was performed on 23 noggin or noggin-like sequences from 15 metazoan species. In agreement with Molina et al. (2011), noggin and noggin-like clades were recovered. The C. fornicata sequence was found within a noggin-like clade (Figure 2E), and contains a 59 amino acid insert between the 5th and 6th cysteine residue within the noggin domain, confirming it is noggin-like.

SMURF (E3 ubiquitin protein ligase) is an antagonist of BMP signaling (Liang et al., 2003), and in vertebrates, two copies are present, whereas in invertebrates, only single orthologs have been identified (Kenny et al., 2014). A single SMURF ortholog was found in the developmental transcriptome of C. fornicata (accession number HM040895). Our phylogenetic analysis of SMURF genes revealed a well-supported clade for vertebrate SMURFs and arthropod SMURFs. Annelid and molluscan SMURFs were found to be polyphyletic (Figure 2F).

3.3. Expression patterns of BMP pathway components

Here, we cloned 4 genes in the BMP pathway including those encoding the ligand Dpp/BMP2–4 (Figure 3), a receptor BMPR1b (Figure 4), and two antagonists: chordin (Figure 6) and noggin-like (Figure 6). We examined their spatiotemporal expression patterns during cleavage and early development, including the time period that covers organizer specification, organizer signaling, and the window of BMP activity (Figure 1A–H), as defined by the experiments described below. We also report on their expression domains later in development, after the proposed window of BMP activity. In addition to these 4 genes, we extended our previous studies that examined the expression of two other BMP signaling mediators: Smad1/5 and Smurf2 (Henry et al., 2010b; Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 4.

Expression of Cfo-bmprbl during development in C. fornicata. A-T. 8-cell to 200+ hpf (larval stages). Refer to detailed descriptions in the Results section. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image. DAPI staining shown in B, D, F, H, J, L corresponds to embryos in A, C, E, G, I, K, respectively. M-P and Q-T show different views of two different embryos, respectively. The animal pole is labeled with an asterisk. Anterior is toward the top of the figure in G-T. A-B. 8-cell embryo. C-D. 16-cell embryo at a different point in the cell divisions, showing changes in expression, presumably based on differences in the cell cycle. E-F. 45 hpf embryo with the 4D clone labeled. G-H. 105 hpf embryo. I-J. 125 hpf embryo. K-L. 130 hpf embryo. M-P. 145 hpf embryo. Q-T. 200 hpf embryo. Black arrowheads point to asymmetric post-trochal ectodermal patch of expression. bp, blastopore; ft, foot; sg, shell gland; st, stomodeum; vl, velar lobe. Scale bar = 50 μm in T.

Figure 6.

Expression of Cfo-noggin-like during development in C. fornicata. A-BB. 8-cell to 196 hpf (larval stages). Refer to detailed descriptions in the Results section. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image. DAPI staining shown in B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P corresponds to embryos in A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O, respectively. Q-R, S-T, U-X, Y-BB show different views of four different embryos, respectively. The animal pole is labeled with an asterisk. Anterior is toward the top of the figure in M-BB. A-B. 8-cell embryo. C-D. 12-cell embryo. E-F. 18-cell embryo. G-H. 25-cell embryo with the 4D clone and its progeny, 4d, labeled. I-J. 40 hpf embryo with the 4D cell labeled. K-L. 60 hpf embryo with the 4D cell labeled, as well as the 4a, 4b, and 4c cells noted. M-N. 94 hpf embryo. O-P. 120 hpf embryo. Q-R. 140 hpf embryo. S-T. 145 hpf embryo. U-X. 180 hpf embryo. Y-BB. 196 hpf embryo. White arrowheads point to a localized area of expression in the neurogenic region of the anterior plate. bp, blastopore; ft, foot; st, stomodeum; vl, velar lobe; vr, velar rudiment. Scale bar = 50 μm in BB.

Figure 7.

Expression of Cfo-smad1/5 during development in C. fornicata. A-BB. 2-cell to 200+ hpf (larval stages). Refer to detailed descriptions in the Results section. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image. DAPI staining shown in B, D, F, H, J, L, N corresponds to embryos in A, C, E, G, I, K, M, respectively. Q-R, S-T, U-X, Y-BB show different views of four different embryos, respectively. The animal pole is labeled with an asterisk. Anterior is toward the top of the figure in M-BB. A-B. 2-cell embryo. C-D. 4-cell embryo. E-F. 8-cell embryo. G-H. 12-cell embryo. I-J. 24-cell embryo with the 4D cell labeled. K-L. 25-cell embryo with the 4D cell labeled, as well as the progeny, 4d, and the 1q1s labeled. M-N. 120 hpf embryo. O. 125 hpf embryo. P. 130 hpf embryo. Q-R. 145 hpf embryo. S-T. 150 hpf embryo. U-X. 180 hpf embryo. Y-BB. 196 hpf embryo. bp, blastopore; ft, foot; pt, prototroch; sg, shell gland; st, stomodeum; vl, velar lobe; vr, velar rudiment. Scale bar = 50 μm in BB.

A single Dpp/BMP2–4 homolog, Cfo-dpp (accession number MN561846) was recovered from the available C. fornicata developmental transcriptomes. Its transcripts were localized predominantly near the nuclei in macromeres during early cleavage stages through the 25-cell stage, similar to what has been previously described for some other mRNAs (Henry et al., 2010b; Figure 3A–F). Beginning at the 25-cell stage, transcripts were also localized to the 4d micromere, as well as in the 4D macromere (Figure 3G–H). In addition, some transcripts were also localized within the 3a and 3d micromeres. However, later expression was mainly localized to the macromeres (Figure 3I–L). At late gastrula stages Cfo-dpp appeared to be expressed around the blastopore in the cells that give rise to ectomesoderm, as well as in the progeny of the 3c2 and 3d2 cells (Figure 3M–R), which are situated along the posterior ridge of the blastopore, and begins to be noted in what are presumed to be neural precursors derived from the 1q1 cells (Figure 3R). Some expression was also noted at later stages, though it becomes more diminished (Figure 3U–BB). Organogenesis stages show transcript localization in distinct cells within the apical/head plate (Figure 3S–T,V), as well as around the mouth (Figure 3S, U–W), the foot rudiment (Figure 3U–W), and the shell gland (Figure 3T, U–X). There is some expression also seen in cells associated with the intestinal rudiment in pre-veliger stage embryos (Figure 3U–W). During early veliger larval stages some expression is detected in the foot rudiment and inside the neck (Figure 3Y–BB).

A BMPR1b homolog, Cfo-bmpr1b, was cloned (accession number MN561847), based on sequence information from the C. fornicata transcriptome. Only one copy of this gene was identified, and it was found to be expressed at the 8-cell stage in a symmetrical pattern in the four macromeres (Figure 4A–B). At the 16-cell stage expression is seen in the macromeres and the 2q micromeres (Figure 4C–D). Like Cfo-dpp, at later stages Cfo-bmpr1b transcripts were localized to near the macromere nuclei during epiboly (Figure 4E–H). At even later stages, during gastrulation and elongation, faint expression is noted around the blastopore in cells that give rise to the ectomesoderm and in the progeny of 3c2 and 3d2 (Figure 4I–L). Organogenesis stages show stronger expression around the mouth (Figure 4M–O), in the shell gland (Figure 4O,P) and in a patch of ectodermal cells on the right side of the post-trochal region (Figure 4M–N,P). This asymmetrical ectodermal territory has been observed for several other transcripts (Osborne et al 2018, Perry et al 2015). Expression during veliger stages is noted in the head, velum, and the foot (Figure 4Q–S), and continues in the ectodermal patch of cells on the right side of the post-trochal region (Figure 4Q–R,T).

We identified a single gene model each for canonical BMP-signaling antagonists, Cfo-schordin (accession number MN561849) and Cfo-noggin-like (accession number MN561848). Cfo-chordin expression begins during gastrulation where it is faintly associated with the nuclei of the macromeres (Figure 5A–B). During later stages, expression is seen around the blastopore/mouth, where it is expressed in ectomesodermal precursors, as well as in the progeny of 3c2 and 3d2 that undergo convergent extension (Figure 5C–D). Faint expression is seen in other cells in the future post-trochal region. During organogenesis stages, expression is seen around the mouth (Figure 5E,G), in the shell gland (Figure 5F,H), and in bilateral ectodermal patches in the post-trochal region (Figure 5G–H). During later organogenesis stages expression is seen in the velar lobes, foot rudiment, and cells located deep within the head (Figure 5I–L). During early veliger stages expression continues to be detected in the velum and the foot (Figure 5M–P).

Figure 5.

Expression of Cfo-chordin during development in C. fornicata. A-P. 40 hpf to 200+ hpf (larval stages). Refer to detailed descriptions in the Results section. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image. DAPI staining shown in B, D corresponds to embryos in A, C, respectively. I-J, K-L, and M-P show different views of three different embryos, respectively. The animal pole is labeled with an asterisk. Anterior is toward the top of the figure in C-P. A-B. 40 hpf embryo shown with the 4D cell labeled. No expression was noted prior to this developmental stage. C-D. 135 hpf embryo. E-F. 140 hpf embryo. G-H. 145 hpf embryo. I-J. 175 hpf embryo. K-L. 180 hpf embryo. M-P. 200 hpf embryo. Black arrowheads point to asymmetric post-trochal ectodermal patch of expression. bp, blastopore; ft, foot; sg, shell gland; sh, shell; st, stomodeum; vr, velar rudiment. Scale bar = 50 μm in P.

Cfo-noggin-like transcripts are transiently localized to the macromeres during early cleavage stages, such as the pattern shown during the 8-cell stage (Figure 6A–B) and the 16-cell stage (Figure 6E–F). Transcripts are more highly localized near the nuclei of the vegetal macromeres. Interspersed between these time points—for example at the 12-cell stage (Figure 6C–D) or the 25-cell stage (Figure 6G–H), we also consistently saw some embryos that were devoid of signal. At later stages, during epiboly, transcripts are localized to the macromeres of the A, B and C quadrants and their progeny (Figure 6I–J, M–P). However, intermediate stages, such as that shown in Figure 6K–L appeared to be devoid of expression. These findings were consistent in multiple batches of embryos. We interpret the transient expression in cleavage stages to be related to the cell cycle, and perhaps more specifically to mRNA loading on and off of the centrosomes. In the leech Helobdella, cell-cycle dependent transcription has been documented for transcription factors and signaling components (Song et al 2004 and Gonzales and Weisblat 2007) and in the mud snail Tritia (Ilyanassa) mRNA cycling between interphase centrosomes and the cell cortex have been documented for many genes (e.g. Kingsley et al 2007). In embryos undergoing organogenesis, expression was seen in distinct cells predominantly located in the developing head (Figure 6Q–X), which might represent neural precursors. Some faint expression could be detected within the esophagus (Figure 6U–V, Y–Z). At later stages, such as in the early veliger larvae, expression appears to be lost (Figure 6AA–BB).

A homolog to Cfo-smad1/5/8 was previously identified in C. fornicata (accession number HM040893, Henry et al., 2010b). Smad1/5/8 is a major transcription factor effector protein of the BMP2–4 signaling pathway (Nohe et al., 2004). At early stages, Cfo-smad1/5/8 mRNA is localized to both macromeres and micromeres (Figure 7A–H). However, after the 25-cell stage, this expression becomes progressively localized to the four 1q1 cells (Figure 7I–L) and the macromeres of the A, B and C quadrants (Figure 7I–N). During late gastrula stages expression is noted around the blastopore, which includes the anterio-lateral, ectomesodermal precursors (Figure 7O–P). Organogenesis stages show expression around the mouth (Figure 7Q,S), as well as in the shell gland (Figure 7R,T), and in the developing velar rudiment/prototrochal band (Figure 7S). Expression during pre-veliger and veliger stages is seen around the mouth, in the velum, in the foot rudiment (e.g. Figure 7V), in cells located deeper within the head, and faintly around the proliferative growth zone of the shell gland (e.g. Figure 7Y–BB).

A homolog of the Smad ubiquitin regulatory factor protein, Cfo-smurf2, which promotes BMP-antagonist complex turnover was also described previously (accession number HM040895, Henry et al., 2010b). Cfo-smurf2 expression is detected at the 2- and 4-cell stages in the cytoplasm around the nucleus (Figure 8A–D). Through the early cleavage stages we found that expression changed, with signal observed in the cytoplasm in some cells/time points, and in the perinuclear area in other cells/timepoints. At later cleavage stages, expression continues to be seen in all cells (Figure 8E–H), Like the situation encountered for Cfo-noggin, we saw some examples in which there was no detectable expression (data not shown), and it is possible that expression and transcript localization may be cell-cycle dependent. At even later cleavage stages Cfo-smurf2 transcripts were only localized to foci adjacent to the nuclei of the macromeres (3A, 3B, 3C, most likely associated with the centrioles, Figure 8I–J). During early gastrulation, only very faint expression could be detected in the progeny of the macromeres of the A, B, and C quadrants in some cases (Figure 8K–N). Expression was no longer detected during later stages of gastrulation (Figure 8O–P).

3.4. BMP4 treatment affects early morphogenesis

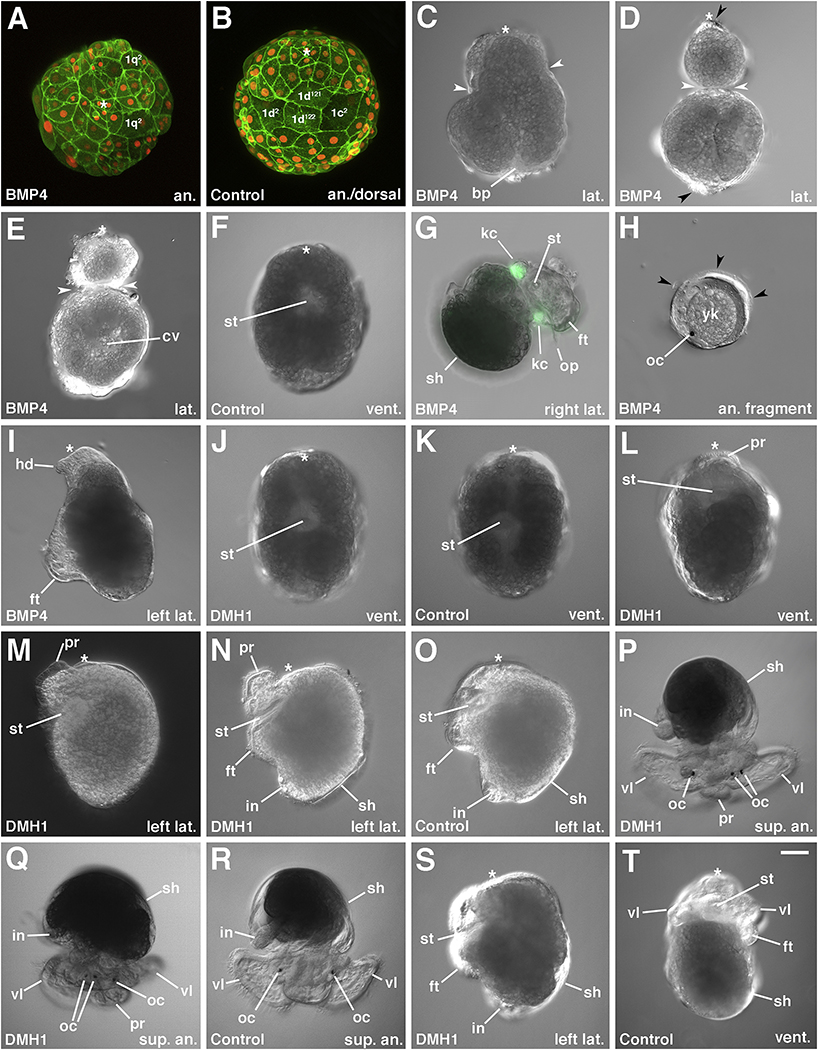

BMP4 is one member of the T ransforming Growth Factor- β superfamily of signaling molecules that plays crucial roles in secondary axis patterning, stem cell maintenance, germline development, and regeneration (e.g. Hamaratoglou et al., 2014; Brazil et al., 2015, Salazar et al., 2016; Lochab and Extavour, 2017). Figure 9 summarizes the experiments performed to define the time window during which adding recombinant BMP4 protein affects development in C. fornicata. Treating embryos for a 24–48 hr period any time before the “morula” stage (when the 4a-4c micromeres are born at approximately 48 hpf; Figure 1H) results in characteristic phenotypes. Initially, embryos treated with BMP4 protein develop normally. Early cleavage divisions of BMP4-treated embryos appear to be identical to those of untreated controls, and one can clearly observe protrusion and precocious division of the 3D macromeres with normal formation of the 4d micromere at the 25-cell stage (data not shown), an indication that normal D-quadrant specification has taken place. Subsequent divisions of the embryo and the stages of compaction and early gastrulation (~48 to ~110 hpf) also appear to be normal (Figures 10A vs. 10B). When control embryos reach ~120–140 hpf, BMP4 protein-treated embryos begin to undergo axial elongation and an abnormal process we call “pinching” (Figures 10C–E, 11B–E, K). These elongation and pinching phenotypes are initiated just before control embryos begin to undergo axial elongation (Figures 11A vs. 11B,F). As they take place, the embryos first become somewhat constricted (also with the narrow end located at the animal pole) or they more typically assume a “pear” or “bowling pin” shape (with the narrow end located at the animal pole; Figures 10C, 11C,K). In either case the pear shape or bowling pin shape emerges and the constriction deepens over time (Figures 10D–E, 11C–E). Eventually the constriction deepens to the point that the cells more anterior to the constriction separate completely from the vegetal cells (Figure 10H); complete separation generally takes place by 7 days of development.

Figure 10.

Development of BMP4 protein and DMH1 treated embryos. Views are indicated in the bottom right corner of each image (sup. an., superior animal). The animal pole is located towards the top of the figure in all cases except A-B, H and N-P. The dorsal side is towards the top of the image in P, Q, and R. Asterisk marks the animal pole. Anterior is toward the top of the figure in A. Embryo undergoing gastrulation at approximately 110 hpf treated for 24 hrs with BMP4 beginning at 24 hpf. This embryo looks comparable to that of a control untreated embryo shown in B, but the arrangement of animal micromere derivatives is not normal. Large flattened cells, presumably 1q2 cells can be seen. B. Control sibling embryo to that shown in A. Note normal arrangement of large 1q2 and other flattened cells derived from 1d1 are gathering along the dorsal side (see Lyons et al., 2017). C. Embryo at approximately 120 hpf treated with BMP4 for 24 hrs beginning at 24 hpf. This embryo is just beginning to undergo constriction (white arrowheads). Blastopore is still located at the posterior, vegetal pole directly opposite the animal pole. D. Embryo at approximately 140 hpf treated with BMP4 for 24 hrs beginning at 24 hpf. Note that upper animal 1q progeny are almost completely separated (at white arrowheads) from the lower vegetal progeny. Ciliated cells reside at the animal and vegetal poles (black arrowheads). E. A second BMP4 treated embryo similar to that shown in D, which focuses on the deeper internal fluid filled cavity located in the vegetal region. F. Untreated control embryo undergoing elongation, at the same age as treated embryos shown in D and E. Note more anterior location of the blastopore/stomodeum on the ventral surface. No constrictions are present. G. Embryo treated with BMP4 for 24 hrs beginning at 24 hpf. This older embryo is approximately 190 hpf and lacks a head. H. Animal 1q fragment derived from an embryo treated for 24 hrs with BMP4 beginning at 24 hpf. In rare cases one can see the development of an ocellus, as shown in this example. Some ciliated cells are present in these fragments (black arrowheads). I. Embryo at approximately 160 hpf treated with BMP4 for 48 hrs beginning at 44 hpf. In this case the animal 1q micromere progeny did not become separated from the vegetal progeny, and a reduced, narrow head has formed. J. Ventral view of an embryo at ~144 hpf treated for 48 hrs with DMH1 beginning at the 8-cell stage. This embryo appears to be normal, like sibling controls (F and K). K. Ventral view of a sibling control embryo for that shown in J. L. Older embryo (~156 hpf) treated with DMH1 beginning at the 8-cell stage for 48 hrs that is forming a protrusion in the head. M. An even older DMH1 treated embryo (168 hpf) treated for 48 hrs beginning just after the birth of 4d (25 hpf) that has a more pronounced anterior protrusion in the head. N. An older DMH1 treated embryo (180 hpf), treated for 48 hrs beginning at 36 hpf. O. Sibling control embryo to that shown in N. P. Embryo treated with DMH1 for 48 hrs beginning at 20 hpf. Note the presence of condensed tissue mass protruding from the head, as well as a supernumerary ocellus on the animal’s left side. Q. Another embryo (230 hpf) treated with DMH1 for 48 hrs beginning at 36 hpf. Note the presence of a condensed tissue mass protruding from the head, as well as a supernumerary ocellus on the veliger’s right side. R. Untreated control veliger for those shown in P and Q. Note presence of only two ocelli and broader rounded head vesicle. S. Embryo (~230 hpf) treated with DMH1 for 48 hrs beginning at 54 hpf, exhibiting normal development. T. Sibling control embryo to that shown in S. bp, blastopore; cv, fluid-filled internal cavity; ft, foot; hd, pointy head; in, intestine; kc, larval kidney; oc, ocellus; op, operculum; pr, anterior protrusion; sh, shell; st, stomodeum; vl, velar lobe. Scale bar in J = 50 μm.

Treatments initiated after the birth of the 4th quartet micromeres (4a-4c) had no effect on development (Figure 9, and compare Figure 11J vs. 11L), while those initiated around the time these cells were born resulted in some embryos exhibiting a weaker phenotype (Figure 9; Figure 10I). In the case of this later phenotype, the progeny of the 1st quartet did not become separated from the rest of the embryo; however, these animal cells still failed to differentiate normally and the embryos exhibited a constricted “pin head” or “headless” form. It should be emphasized that treatments initiated prior to 48 hpf, but after the specification of the D quadrant (blue vertical bar in Figure 9; Figure 1C), and alter 4d organizer signaling (tan vertical bar in Figure 9; Figure 1E), resulted in embryos with these characteristic BMP4 phenotypes (signified by green horizontal bars, Figure 9).

3.5. BMP4 protein-induced pinching occurs between the 1st and 2nd quartet

Previous lineage tracing studies established the origins, early morphogenesis, and ultimate fates of the cells within the various micromere quartets (Figure 1; Hejnol et al., 2007, Lyons et al., 2015, 2017). Figure 11A–B shows examples of control and BMP4 protein-treated embryos, respectively, in which one micromere clone (the 1c clone consisting of a large, flattened identifiable 1c2 cell in the center and the multi-cell 1c1 sub-clone) has been labelled with Dil. The shape of the flattened 1c2 cells are similar to those of controls. On the other hand, the shape of the 1c1 clones appear to occupy less area compared to those in controls (Figure 11A–B). When these 1q-labelled embryos are allowed to develop further, it is clear that the circumferential line of constriction/pinching is located exactly between the progeny of the first and second quartet micromeres (Figure 11C–D). It is unclear whether this process happens through extracellular changes such as differential cell adhesion between cells, or via intracellular mechanical forces with cells driven by the cytoskeleton, or as the results of muscle contractions. For the latter at least, the answer appears to be no. Muscles normally develop from 4d, 3a, and 3b cells, and the progeny of those cells are retained in the vegetal fragments only (e.g., 4d clone shown in Figure 11K). Staining with phalloidin confirms that no muscles have formed at these stages of development, nor do they form in the animal fragments (data not shown). Therefore, muscular contractions could not play a role in the pinching process.

As the process of constriction takes place, the blastopore can be seen initially at the vegetal pole where there is a shallow divot opposite the animal constricted end (compare Figures 10C and 11E vs. Figures 10F and 11F). As the constriction deepens, the blastopore moves somewhat anteriorly onto the future ventral side of the embryo, but its relocation is delayed and it remains in a relatively posterior location compared to control embryos, as they undergo the process of elongation (compare Figure 11C, E vs. F). Before the animal and vegetal fragments undergo complete separation, one can observe that the vegetal fragments initially contain a central fluid-filled cavity (Figure 10E), which appears to be lost later in development.

3.6. Post-pinching, the animal fragments of BMP4-treated embryos are radialized

After the pinching process separates the animal/anterior fragments from the vegetal/posterior fragments, the animal fragments do not develop normally. These fragments never exhibit any obvious signs of dorsal-ventral patterning, and thus we consider them to be radialized (Figure 10H). These pieces are spherical, consisting of an outer layer of ectoderm derived solely from the 1q cells surrounding pinched-off pieces of the yolk-filled macromeres (verified by lineage tracers, data not shown). These spherical animal fragments eventually become ciliated, and one can observe that these include the 1q2 cells (Figure 11C–D). Those 1q2 cells behave similarly to those present in control embryos, as they are both cleavage arrested, ciliated, and highly flattened cells (compare Figures 10A, 11B–D vs. 10B, 11A). These 1q2 cells eventually contract, become more rounded and protrude from the surface of those embryoids (data not shown), in a process that appears to be similar to that which takes place in control embryos just before they are lost from the embryo (Lyons et al., 2017). Some longer cilia can also be seen, which appear similar to velar cilia, though no discrete velar lobes are formed. Otherwise, little differentiation takes place within these radialized animal fragments. Less than 4% of the cases form ocelli and more typically only one ocellus (Figure 10H) or a smaller fragmented ocellus is present in those cases, which appear between 7– 8 days of development. We examined the expression of Cfo-Six3/6 in the BMP4 treated embryos, as an early marker of neural development. In these cases expression was diminished, though we did observe some discrete areas of expression in the anterior constrictions (compare Figure 12A vs. 12B). Little or no recognizable staining for FMRF-amide was found inside these animal fragments (data not shown). Typically, these small animal fragments were found to have disintegrated by 9–10 days of development.

Figure 12.

anti-FMRFamide labeling of neurons in control, BMP4 and DMH1 treated embryos. A-B, E-J show superior animal views and C-D show right lateral views. White arrowheads in A, E, G, I point to ocelli. The cerebral commissure is noted with a white arrowhead in B, F, H, J. A. Control early veliger larva (approximately 228 hpf) with velar lobes, shell and two ocelli with B, corresponding fluorescence micrograph showing green fluorescent FMRFamide stained neurons on the CNS. A long fine neuron derived from the 2d micromere is also visible (green arrowhead, see Lyons et al., 2015). C. Headless BMP4 treated case (228 hpf) that was treated for 48 hrs beginning at 20 hpf. A small mass of ciliated ectoderm lies in place of the head (most likely derived from the 2nd quartet micromeres). Though delayed, the post-trochal region has developed normally, complete with an intestine, shell, foot and operculum. D. Corresponding fluorescence micrograph to that in C, showing absence of FMRFamide stained CNS neurons. However, the long fine neuron derived from the 2d micromere (green arrowhead) is still present. E. DMH1 treated case (228 hpf), which appears nearly identical to untreated controls (compare with A). The embryo was treated for 48 hrs beginning at 20 hpf. A prominent head protrusion is seen in this early veliger and there is one supernumerary ocellus on the left side. F. Corresponding fluorescence micrograph to that in E, showing green fluorescent FMRFamide stained neurons on the CNS, as well as long fine neuron derived from the 2d micromere (green arrowhead). FMRFamide staining also appears similar to that of controls. G. An older control veliger larva (~240 hpf), and corresponding fluorescence micrograph (H), showing presence of FMRFamide stained CNS neurons. The anterior and posterior visceral loops are also visible, as labeled. I. An older DMHI-treated veliger larva (~240 hpf). J. Corresponding fluorescence micrograph to that in I, showing presence of FMRFamide stained CNS neurons. Note thickened cerebral commissure (white arrowhead). The anterior and posterior visceral loops are also visible, as labeled. The commissure connecting the cerebral ganglia appears to be thickened, compared to the control in H. avl, anterior visceral loops; ce, ciliated epithelium; op, operculum; pr, anterior protrusion; pvl, posterior visceral loop; sh, shell; st, stomodeum; vl, velar lobe. Scale bar in J = 50 μm for A-F, and 70 pm for G-J.

3.7. Post pinching, vegetal fragments from BMP4 protein-treated embryos form headless embryos that exhibit dorsal-ventral patterning

In contrast to the animal fragments that form in BMP4 protein-treated embryos, the vegetal fragments can develop rather normally. While some of these partial embryos disintegrate before they undergo differentiation, those that survive develop post-trochal regions with clear signs of bilateral and dorso-ventral asymmetry and eventually form “headless” embryos (Figure 10G, I; Figure 12C–D). These possess a foot with an operculum and bilateral statocysts. All cases formed bilateral autofluorescent crystal cells and larval absorptive cells (Figure 10G; Figure 11K). Differentiated neurons are seen in these embryoids, including one prominent neuron labeled by FMRF-amide that is characteristic of that derived from the second quartet cell 2d (see Lyons et al., 2015) (compare Figure 12A–B vs. 12C–D). They may also form a reduced shell on the dorsal surface (Figure 12C). These headless embryos may possess a blind passageway located closer to the animal pole, which could be the stomodeum/esophagus though its relationship to the blastopore is uncertain. Within these vegetal fragments, the 4d mesentoblast forms bilateral mesodermal bands, and they also form the 1mL/R and 3mL/R cells of the intestinal rudiment (Figure 11K). At later stages, an intestine can be seen in some of these embryos. Other derivatives of the mesentoblast also appear to undergo normal differentiation. For instance, in all cases a pair of bilateral external kidneys can be seen to form in the vegetal halves and this includes the autofluorescent crystal cells (e.g. Figure 10G; Figure 11K). [Note that although Figure 11 shows the fluorescent kidney cells and the lineage tracer both in green fluorescence, we are able to distinguish the autofluorescent crystal cells from the fluorescent dextran label in the 4d lineage because we previously carried out an extensive study of the 4d fate map using both red and green lineage tracers (Lyons et al., 2012).] Ultimately, these vegetal fragments do not survive and most have disintegrated by 9 to 10 days of development.

When embryos are exposed to BMP4 protein at later stages of development, i.e., closer to the time the other fourth quartet cells are born, the degree of constriction between the first quartet derivatives and the vegetal portion of the embryo is much reduced and the first quartet sister cells remain attached to the vegetal cells (Figure 10I). These embryos do not form a well differentiated head or velum, and instead possess a highly constricted spike of transparent ciliated tissue (headless or “pinhead” phenotype). Ocelli may or may not be present within these cases.

3.8. DMH1 treatment affects neural development, but not signaling activity from the organizer

DMH1 (Dorsomorphin Homolog 1) is a small molecule inhibitor, which is selective for the activin receptor-like kinase 2 (ALK-2), a type I BMP receptor (Hao et al., 2010), but also can inhibit ALK-1 and ALK-3 with lower affinity. Early development in DMHI-treated embryos appears to be identical to controls (Figure 10J vs. 10K), until the initial stages of early organogenesis are reached. During early organogenesis one can observe a pronounced protrusion forming in the head. This protrusion phenotype can be readily observed between 6 to 7 days of development (Figure 10L). This region gives rise to the ciliated apical plate, which is thought to be sensory in function and is derived from the 1q1 cells (including cells that give rise to the brain and ocelli, see Hejnol et al., 2007, Lyons et al., 2017). At later stages this protrusion enlarges and extends outwards toward the ventral surface, just anterior to the mouth (compare Figure 10M–N vs. 10O). In some experiments this protrusion disappeared after further development (particularly those cases treated just before the birth of the 4a, 4b, and 4c micromeres. Otherwise, development appears to be normal with one additional difference. In DMH1-treated cases, there are enlarged apical ganglia with duplicated ocelli in up to 50% of the cases (Figure 10P,Q; Figure 12E, I). The pigmented ocelli appear generally between 7 to 8 days of development. These ectopic ocelli appear to be intact, full-size and are not the result of fragmented ocelli. During normal development, the left and right ocelli are derived from the 1a1 and 1c1 cells, respectively (Hejnol et al., 2007; Figure 1B,M–O). The extra ocelli in DMH1-treated embryos appear on either the right or the left side in close proximity with the neighboring ocellus located there. This suggests that the ectopic ocelli are derived from the same cells that normally give rise to the normal ocelli, and not coming from another lineage, such as 1b or 1d. Duplicated ocelli were not observed in control embryos. We also examined the expression of Six3/6 in these embryos as an early marker of neural development during elongation stages. In some of these cases we observed expanded regions of ectopic expression in the developing head (compare Figure 13C,C’,C” vs. 13D,D’,D”). At later stages, the arrangement of FMRF-amide labeled neurons appears fairly normal in DMH1 treated cases with some subtle differences. For example, the morphology of the commissure connecting the cerebral ganglia appears to be altered and thickened, compared to controls (compare Figure 12A–B vs. 12E–F and 12G–H vs. 12I–J).

Figure 13.

Cfo-six3/6 expression in control, BMP4- and DMHI-treated embryos. Embryos were treated for 48 hrs beginning at 20 hpf. Views are as labeled. A. Control embryo showing normal Cfo-six3/6 expression at approximately 135 hpf. Note foci of Cfo-six3/6 expression in presumptive neurogenic cells, located in the future head region (white arrowheads). These areas of expression correspond to regions that presumably give rise to future cerebral ganglia and ocelli. Some expression is also seen around the developing stomodeum. B. Example of a sibling embryo to that shown in A, which was treated with BMP4. This embryo has undergone constriction. Note presence of some Cfo-six3/6 expression in the anterior fragment, derived from the first quartet micromeres (white arrowheads). C-C”. Control embryo showing normal Cfo-six3/6 expression at approximately 130 hpf. Note regions of expression in the future head (white arrowheads). C’. Corresponding anterior (animal pole) view. C”. Corresponding dorsal view. D-D”. Example of a sibling embryo treated with DMH1. Note increased expression of Cfo-six3/6, including ectopic sites of expression in the future head region, as indicated by the white arrowheads. D’. Corresponding anterior (animal pole) view. D”. Corresponding dorsal view. st, stomodeum. Scale bar in D” = 50 μm.

Similar phenotypes are seen regardless of when the embryos were exposed to DMH1, as long as the drug is administered prior to the birth of the 4q cells (Figure 9). DMH1-treated embryos survive much longer (at least 2 weeks) compared to the BMP4 treated cases. No effects were noted when embryos were treated after this time interval. Similar to the time window for BMP4 protein treatments, treatments with DMH1 initiated prior to 48 hpf, but after the specification of the D quadrant (blue vertical bar in Figure 9; see also Figure 1C) and after the end of 4d organizer signaling (tan vertical bar in Figure 9; see also Figure 1E), resulted in embryos with characteristic DMH1 phenotypes (signified by green horizontal bars; Figure 9).

4. Discussion

4.1. BMP signaling has an ancient role in metazoan dorsal ventral patterning and neural-epidermal fate specification

The developmental roles for BMP signaling have been studied extensively in bilaterians and BMP signaling is widely associated with specifying the dorsal-ventral axis and neural/epidermal fates (Mizutani and Bier, 2008; Hejnol and Lowe, 2015; Martín-Durán et al., 2018). In Drosophila and vertebrates the expression patterns of the transcripts for BMP ligands and their antagonists are mutually exclusive, with BMPs expressed on the side of the embryo that will develop into epidermal and peripheral nervous system tissue, while BMP antagonists are expressed on the side that will develop into neural tissue belonging to the central nervous system (Lowe et al., 2006). In other species, such as in sea urchins and cnidarians, mRNAs for BMP and its antagonists are asymmetrically expressed on the same side of the embryo, but BMP signaling is still involved in dorsal-ventral/neural-epidermal specification because the proteins diffuse away from their source and interact in the extracellular matrix to influence cell fate in the surrounding cells (Bier 2011; Lapraz et al., 2009). Although BMP signaling has an ancestral role in axial patterning, the components can be deployed in diverse ways, and studying a wider range of animals may uncover further functional diversity.

Dorsal-ventral patterning downstream of BMP signaling generally occurs in two phases (e.g., in vertebrates). First, during pre-gastrula or gastrula stages, ectoderm segregates into two domains: where BMP signaling is high, cells will become epidermal, and where BMP antagonists are present, BMP signaling is low and cells will become neural. Later, at post-gastrula stages, a second phase of BMP signaling further patterns multiple germ layers in deuterostomes and ecdysozoans. While both phases of BMP signaling appear to be widespread and thus ancestral for metazoan body plan development, it is not fully understood how this conserved signaling pathway has been modified during evolution to give rise to morphological diversity. Gaps in our knowledge are particularly prevalent within the large and diverse superclade Spiralia, which is severely under-sampled compared to deuterostomes and ecdysozoans. For example, two recent molecular studies of the spiralian organizer, which patterns embryonic cell fates along the dorsal-ventral axis, found that BMP signaling is involved in organizer signaling in a mollusc (Lambert et al., 2016), but not in an annelid (Lanza and Seaver, 2018; Corbet et al., 2018). Thus, we set out to examine the role of BMP signaling in the development of the slipper snail C. fornicata, which we have developed as an experimental model system among molluscs (Henry et al., 2010a; Henry and Lyons, 2016; Lesoway and Henry, 2019). Here, we found that BMP signaling is not involved in D quadrant specification or 4d organizer activity in C. fornicata, but rather is involved later during development - downstream of organizer activity - in regulating cell fate specification of anterior neural cells derived from the first quartet of micromeres.

4.2. BMP signaling in C. fornicata is not involved in organizer signaling, but is involved in anterior neural/epidermal development