Abstract

PURPOSE:

Rates of burnout among health care professionals are rising. Oncology nurses are at the forefront of cancer care, and maintenance of their well-being is crucial to delivering high-quality care to people with cancer. The purpose of this pilot study was to implement a novel intervention, Storytelling Through Music, and examine the effects on depression, insomnia, loneliness, self-awareness, self-compassion, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion satisfaction in oncology nurses.

METHODS:

This two-group (intervention and control), quasi-experimental study of a 6-week intervention combined storytelling, reflective writing, songwriting, and stress management skills.

RESULTS:

Participants (N = 43) were predominately white (98%), with 27% reporting Hispanic ethnicity, and female (95%); their average oncology experience was 8.5 years. Both groups improved significantly over time on all measures. Compared with the control group, participants in the intervention group also had significantly less loneliness (F[3, 98] = 7.46; P < .001) and insomnia (F[3, 120] = 5.77; P < .001) and greater self-compassion (F[3, 105] = 2.88; P < .05) and self-awareness (F[3, 120] = 2.42; P < .10).

CONCLUSION:

There are few opportunities for health care professionals to reflect on the impact of caregiving. The Storytelling Through Music intervention provided a structured space for reflection by participants, individually and among their peers, which decreased loneliness and increased self-compassion. Both factors relate to the burnout that affects the oncology health care workforce.

INTRODUCTION

Rising rates of compassion fatigue and burnout threaten the well-being and health of both clinicians and patients and must be a national priority.1-3 More than half of all US physicians and nurses report burnout symptoms,1 and these symptoms are arising at earlier points in their careers.2 The personal consequences of compassion fatigue are classified as physical, behavioral, psychological, and spiritual and can affect the health care professional’s (HCP’s) identity, understanding of self, and existential well-being.4 Burnout has been directly linked to depression, loneliness, a decreased quality of life, and even personal harm.1

From an organizational standpoint, decreased well-being leads to decreased quality of patient care, on-the-job errors, and increased staff turnover.1,5 It is caused by increasing work demands, higher acuity, and staff shortages as well as repeated exposure to patient suffering, cumulative patient death, moral distress, and a lack of time to address the psychosocial implications of caregiving.6-8 Research indicates that the health outcomes for the patient are affected by the well-being of HCPs.5

The nature of oncology work involves rich and dynamic relationships, existential questions of life and death, and repeated exposure to patient suffering and death.6 The impact of cumulative professional grief may be an antecedent to compassion fatigue and burnout in oncology HCPs. Studies of oncology HCPs’ experiences with grief reveal that nurses and physicians avoid their emotional expression of grief.6,7,9 Innovative interventions to teach them how to cope with the dynamic emotions they experience while caring for patients with cancer are limited.

Expressive writing has been used to improve well-being of many populations and has been shown to improve immune system functioning,10 mood,11 and cognitive functioning.12 In addition, music has been studied across cultures. Music is a socially acceptable form of self-expression that encourages social interaction.13 In HCPs, the use of music has been found to reduce burnout11 and assist in revealing true emotions linked to work stress.14 However, in a recent systematic review of expressive arts interventions used to improve HCP well-being, the studies that combined expressive arts interventions with psycho-education had more positive outcomes on the emotional well-being of HCPs than single-modality interventions.15

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of implementing a novel, multidimensional intervention, Storytelling Through Music (STM), with oncology nurses. STM uses storytelling, reflective writing, songwriting, and stress management skills over a 6-week period. Well-being was examined by evaluating professional factors (burnout, secondary traumatic stress [STS], and compassion satisfaction [CS]), personal factors that have been shown to be related to compassion fatigue and burnout (depression, insomnia, and loneliness),1,16 and protective factors to enhance well-being (self-awareness and self-compassion).16,17 The following hypotheses were tested: Compared with the control group, participants in the intervention group would show significantly greater improvements in measures of professional well-being (burnout, STS, and CS), personal well-being (depression, insomnia, and loneliness), and protective factors to enhance well-being (self-awareness and self-compassion).

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

The interrelated constructs of burnout and compassion fatigue do not fully represent the emotional stress experienced by oncology professionals.18 For this reason, three theoretical models were integrated to create the conceptual framework for this study: Transactional Model of Stress and Coping,19 model of health professionals’ grieving process,20 and self-awareness–based model of self-care.17 The constructs of stress and coping from Lazarus and Folkman19 underlie the framework. Coping with the emotional experience of caring for people with cancer is further explained by Papadatou’s20 model of HCPs’ grief and Kearney and Weininger’s17 conceptualization of outcomes on the basis of the HCPs’ level of self-awareness to their emotional experience.

METHODS

The study was a two-group (intervention and control), quasi-experimental design. After institutional review board approval (2018-05-0061), data were collected at two time points before the intervention and two time points after the intervention. The two pre-intervention data points were used to control for the testing effect, while all four data collection points provided a stronger test of the intervention than using a simple pre/post design.21 The two pre-intervention data points were separated by 2 weeks. The third data point was collected at the end of the intervention, and the fourth data point was collected approximately 1 month later.

The recommended sample size was calculated with G*Power 3.1.7 software.22 To achieve statistical significance (α = .10), assuming a power of 0.8, a moderate effect size (F) of 0.2, and correlation of 0.6 between measures, a sample size of at least 24 per group would be needed. The α-level was set at P < .10 because the focus of the inferential analysis was to identify potential meaningful differences in outcomes that could be followed up in a larger randomized trial.23

Participants

Participants were recruited over 4 months in central Texas and came from community and academic cancer settings. Methods of recruitment included e-mail (through an Oncology Nursing Society chapter LISTSERV), social media, flyers, presentations, and word of mouth. Inclusion criteria were > 18 years of age; ability to read and speak English; licensed registered nurse with ≥ 1 years of oncology experience delivering direct patient care; and if not currently working in oncology, having had worked in oncology within the past 5 years. The inclusion criteria were designed to recruit nurses with current or recent cancer care experience who worked in the field long enough to have experienced the stress of patient loss.

Four intervention cohorts were created on the basis of rolling recruitment. Eligible nurses who were unable to participate in the intervention were offered the option of participating in the control group. Written informed consent from each participant was obtained before data collection. Each participant received a $50 gift card at the end of data collection.

STM Intervention

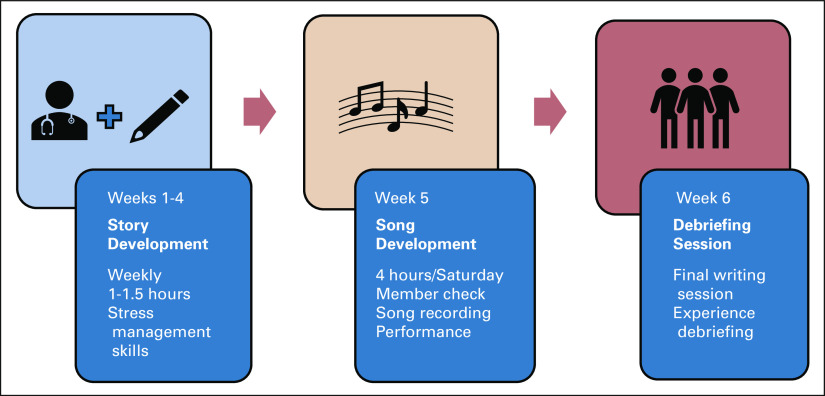

STM is a 6-week intervention (Fig 1). It was cofacilitated by an advanced practice oncology nurse and a singer-songwriter who had previously conducted a similar intervention.24 During the first 4 weeks, participants met weekly for approximately 1-1.5 hours and were provided with writing prompts to help them to develop their caregiving stories. A 10-minute, self-care lesson (guided breathing, body scan, self-compassion) was taught at the beginning of each session.

Fig 1.

Storytelling Through Music intervention.

During the 5th week, each participant was paired with a songwriter who worked with the participant to turn his or her story into a song. At the end of the week, the participants and songwriters performed the stories and songs for each cohort. The last writing session (week 6) facilitated participant debriefing about this experience. Participants were also given a recording of their song and asked to interact with it (sing along, listen only, or both) for 1 month. To enhance intervention fidelity, the same researchers implemented the intervention in all four cohorts.

The data collected suggested that STM was feasible and acceptable to this group of participants. Ninety-eight percent of the intervention sessions were attended, and 100% of the stories and songs were completed. Additional information about the STM intervention components, feasibility, acceptability, and songwriter recruitment and screening is described elsewhere (Phillips et al, manuscript submitted for publication).

Measures

Individual factors.

An information sheet was used to collect background data to describe the sample.

Depression.

The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) depression short-form scale (8 items) was used. The PROMIS scale’s reliability and validity have been reported for various populations.25 Individual item ratings are summed. Higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. Reliability in this study was α = .90.

Insomnia.

The Insomnia Severity Index (7 items) assesses the nature, severity, and impact of insomnia.26,27 A 5-point Likert scale is used to rate each item (eg, 0 = no problem, 4 = very severe problem), which yields a total score that ranges from 0 to 28. Previous studies have reported adequate psychometric properties,26 and this summative scale has been used with HCPs.16 Higher scores indicate higher levels of insomnia. Reliability in this study was α = .84.

Loneliness.

The University of California, Los Angeles, Loneliness Scale (20 items) measures subjective feelings of loneliness and social isolation.28 Participants rate each item from 0 to 3 (never to often). Higher scores indicate more loneliness. The measure is reliable (α = .89-.94) and test-retest reliability over a 1-year period is r = 0.73.28 Reliability in this study was α = .97. The scale is strong in convergent and construct validity28 and has been used in previous studies with HCPs.29

Self-awareness.

The Self-Reflection and Insight Scale30 (20 items) assesses self-reflection (12 items; a tendency to think about and evaluate thoughts, actions, and feelings) and insight (8 items; the clarity of experience and self-knowledge). Items are rated on 7-point scales (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicate higher amounts of the construct. The scale has been validated with different groups, including nurses.30,31 Both internal consistency and test-retest reliability are high.31 Reliability in this study was α = .90 on the self-reflection subscale and α = .83 on the insight subscale.

Self-compassion.

On the Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; 26 items), a higher score indicates more of the construct. Used in a wide variety of populations, including nurses,32 the SCS demonstrates good reliability and discriminate validity.27,33 Reliability in this study was α = .96.

Professional well-being.

The three subscales of the Professional Quality of Life (ProQOL) scale measure professional well-being: burnout, STS, and CS. Burnout and STS assess the risk for compassion fatigue.34 The CS subscale yields a separate score. Higher scores on all subscales indicate more of the construct. All subscales had good, previously reported, internal reliability (burnout = .75, STS = .81, and CS = .87).34 Reliability in this study was α = .78 (burnout), α = .83 (STS), and α = .92 (CS). Used with many professional groups, the construct validity is strong.34,35

Data Analysis

Survey data were collected through Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and analyzed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY) software. After determining that data were missing at random, mean substitution was used if < 15% of item values on a scale were missing. Once preliminary analysis of assumptions and internal consistency was completed, background data were analyzed using descriptive statistics.

Separate 2 × 4 mixed-repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were performed to examine changes between groups across the four time points—baseline (pre-intervention time 1 [T1] and T2), immediate postintervention (T3), and 1-month postintervention (T4)—on each outcome measure. Effect sizes associated with the differences over time and the interactions between time and groups were calculated and reported.

RESULTS

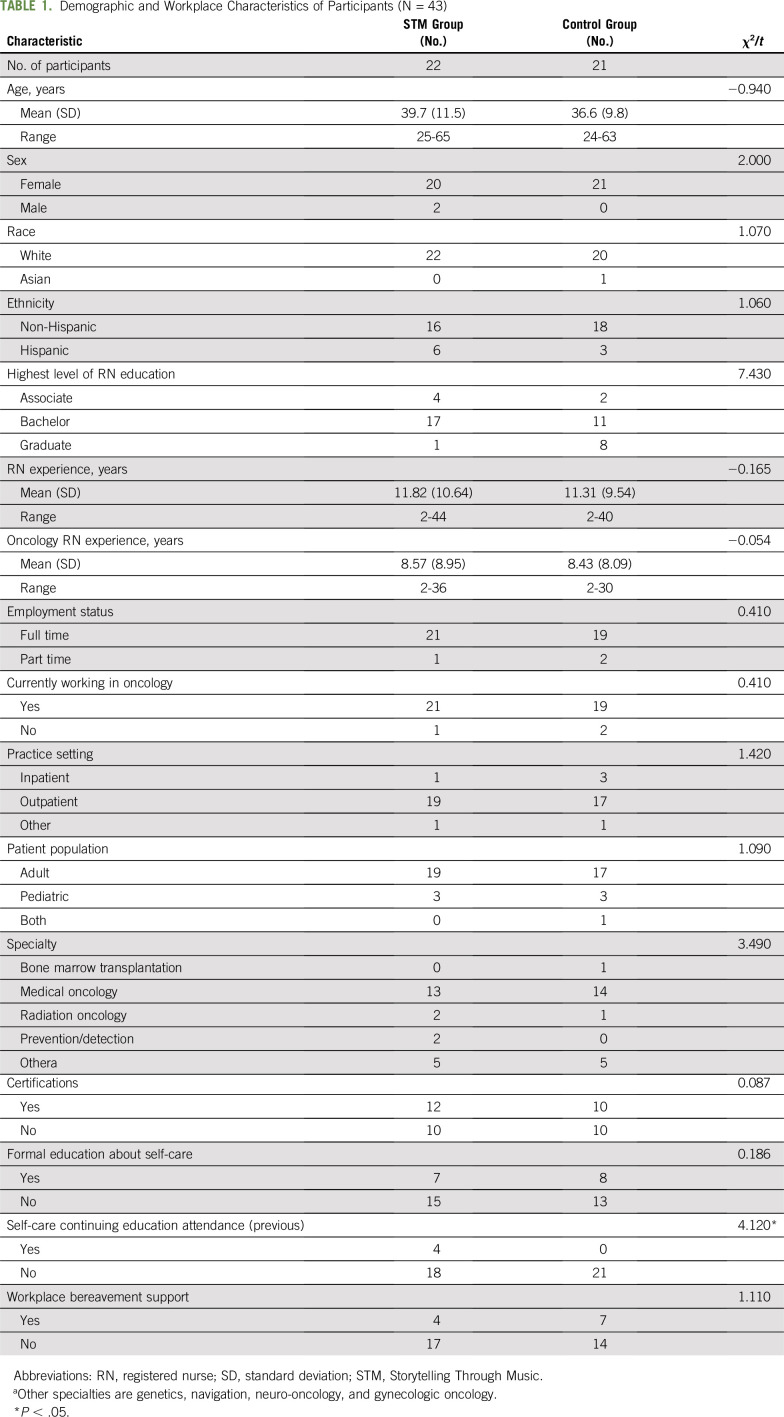

Fifty-one oncology nurses expressed interest in the study, and 86% of that group participated (N = 43). The only significant difference between the control and intervention groups was on self-care continuing education attendance (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Workplace Characteristics of Participants (N = 43)

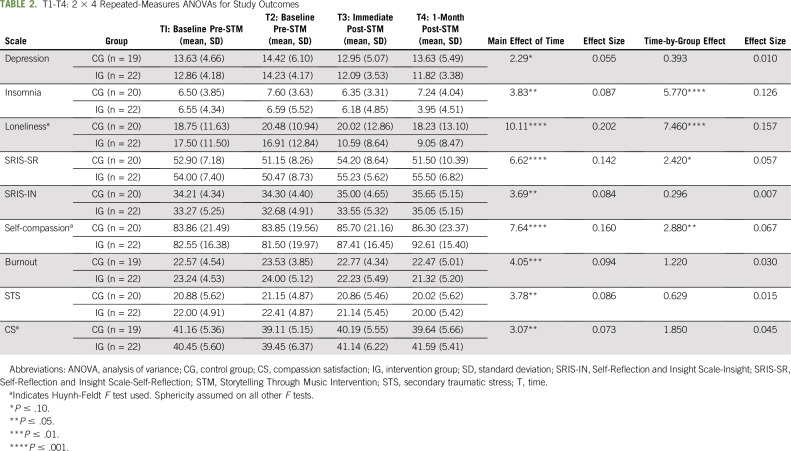

Paired t tests between outcomes at T1 and T2 yielded few differences. Most differences occurred between T2 and T3 and T2 and T4. Only two outcome measures indicated a significant difference between T1 and T2: Self-reflection and CS both decreased significantly. Table 2 lists a comparison of means (standard deviations) and the results of the ANOVA tests.

TABLE 2.

T1-T4: 2 × 4 Repeated-Measures ANOVAs for Study Outcomes

Outcomes Related to Professional Well-Being

Outcome variables related to professional well-being were captured on the ProQOL scale (burnout, STS, and CS). All measures had a significant main effect of time, but no time-by-group interactions were significant. The effect size associated with the time-by-group interaction for each of these measures was small. When comparing differences between time points separately for the intervention and control groups, there were a few instances when the intervention group improved significantly and the control group did not, but the pattern was not consistent.

Outcomes Related to Personal Well-Being

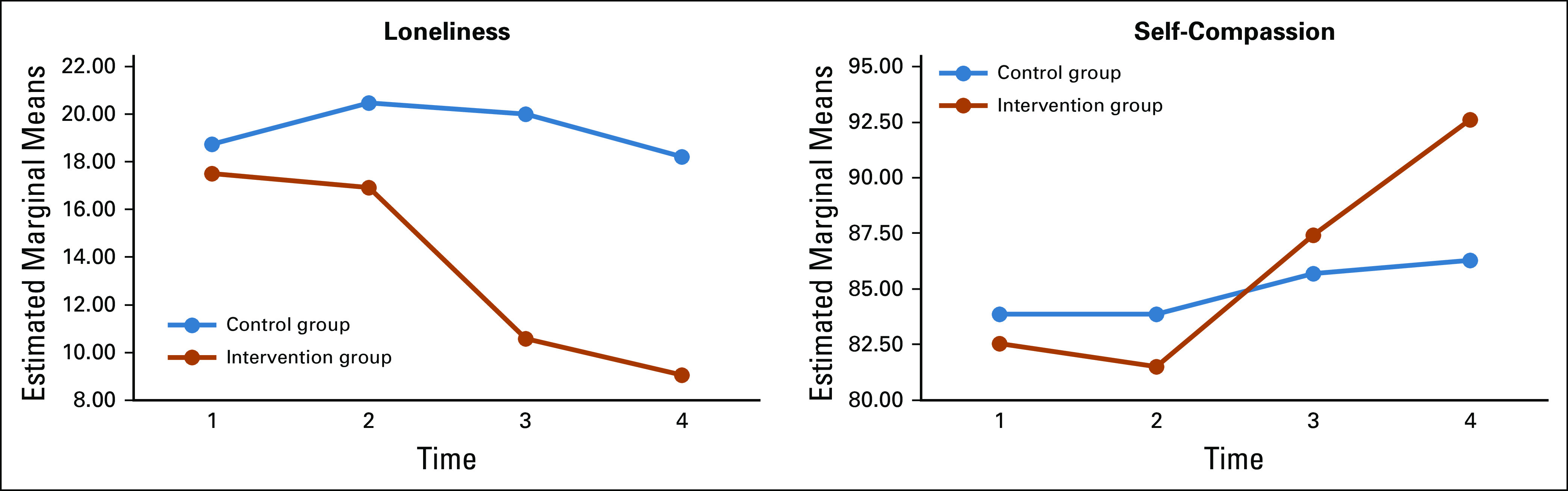

All outcome variables related to personal well-being (depression, insomnia, and loneliness) showed a statistically significant main effect for time. The time-by-group interaction effect was significant for insomnia (F[3, 120] = 5.77; P < .001 [ = .126]) and loneliness (F[3, 98] = 7.46; P < .001 [ = .157]; Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Changes in loneliness and self-compassion scores for intervention and control groups.

Additional evaluation of the depression scores was undertaken because of the different trends in mean scores between the intervention and control groups. The largest decrease in the control group was from T2 to T3, and then depression increased at T4 back to the baseline value. In contrast, the intervention group maintained a decrease in depression from T2 through T4. Paired t tests between T2 and T4 revealed a significant decrease for the intervention group (t[21] = 2.278; P < .05) and a nonsignificant difference for the control group (t[18] = 0.541; P > .10).

Outcomes Related to Protective Factors to Enhance Well-Being

Self-compassion and self-awareness were proposed to enhance well-being. There was a statistically significant main effect for time on all variables but few significant time-by-group interaction effects. A statistically significant time-by-group effect was observed for self-compassion (F[3, 105] = 2.88; P < .05 [ = .067]; Fig 2). There was a significant time-by-group effect on the self-reflection subscale (F[3, 120] = 2.42; P < .10 [ = .057]). Post hoc analysis of the intervention effect on the insight subscale showed significant improvement in the intervention group between T2 and T4 (P < .05).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this pilot study was to examine the effect of STM on oncology nurses’ well-being. The differential pattern of scores across time revealed that the intervention group typically had greater improvements over time than the control group, although not all differences were statistically significant. The significant changes over time for both groups suggest that even control group participants had an improvement in many outcomes. There are two possible explanations for this effect. First, completion of the surveys may have acted as an intervention. By taking the surveys, the control group participants were exposed to concepts that may have increased their awareness of and attention to their emotional well-being. Second, some participants in the intervention group worked with and shared their experiences with participants in the control group, which also could have affected the results.

The intention of STM is to provide a space for oncology nurses to safely discuss work-related emotions, thereby increasing awareness of the depth of emotion that they and their colleagues experience routinely. While doing so, participants are taught self-care skills to use when the emotions arise during the intervention, a skill that can be translated to the work environment later. The exposure to and discussion of emotions occurred in a group setting, which allowed participants to gain an understanding of their shared experience and may have contributed to awareness of their collective suffering. Intervention participants also exhibited increased self-awareness and self-compassion and decreased insomnia and loneliness.

Loneliness has been described in the bereavement literature as a gateway symptom for additional depressive symptoms and a predictor for other mental and physical health consequences.36 Another study showed a positive correlation between loneliness and work-related burnout scores, while more friend- and colleague-based social support was inversely related to burnout and loneliness.37 Participants in the STM intervention had a greater decrease in loneliness compared with the control group. One possible explanation for this effect may be the experience of cognitive dissonance when there is a lack of consistency between beliefs and behavior.38 In health care, there is little opportunity for HCPs to reflect on the impact caregiving has on self. This leads to coping in isolation. Dissonance in the experience may result when HCPs isolate but at the same time desire to continue to connect to and be emotionally available with their patients. STM provided a setting for the participants to discuss their emotions, which may have brought internal consistency to participants who experienced cognitive dissonance. Furthermore, participants completed the study in a group setting where they learned that they were not alone in this experience. There is little intervention research that has targeted loneliness, yet it is an important variable because it can lead to and be a symptom of burnout.

For participants in the intervention group, increase in self-compassion was another important outcome. Self-compassion can build resilience against depression, anxiety, stress, burnout, and emotional exhaustion39 by increasing life satisfaction, optimism, and social connectedness.33 Not only is self-compassion an important component for HCPs in maintaining their health while caregiving but also it is reflected in the care they give to patients. Research suggests that individuals who are more critical of themselves also tend to be more critical of others, such as their patients.40 Conversely, when a person is able to experience the full range of emotions, they are able to hold space for this range of emotions in others and can interact with others more authentically.40 Thus, to care well for others, one must first care for oneself.

This study did not show a difference in the relative gain between groups on burnout, STS, and CS. More time may be needed to have a differential effect on these variables. Another consideration is that the items within the ProQOL may not resonate with the participants. In the intervention group, participants discussed feeling burned out and emotionally exhausted, yet their scores did not indicate high levels of burnout or STS. When evaluating the individual items on the scale, it is possible that these participants were not willing to say that patient care hurts them, which may affect their responses. Moreover, the emotional exhaustion described by the participants was another construct not captured by the ProQOL scale.

There are limitations to this study, including nonrandomized group assignment, small sample size, and convenience sampling. These limit generalizability and increase the risk for selection bias. Compared with other oncology nurses, the nurses who chose to participate may be more drawn to this type of intervention. In addition, the sample was heavily represented by outpatient nurses, and the intervention study should be replicated with larger groups and hospital-based nurses.

The National Academy of Medicine declared that clinician well-being must be a national priority1 and made a call for high-quality intervention studies aimed at addressing burnout in clinicians. This study provides initial evidence for improved well-being with the use of STM. However, study participants were volunteers who completed it on their own time outside the regularly scheduled workday. To enhance participation in wellness programs, one policy recommendation is to connect programs to mandatory competency training required by accrediting bodies so that institutions can make clinician well-being a priority.

There are numerous workplace implications. Additional work is needed to understand the feasibility and effect of STM with inpatient nurses. Implementation of this intervention with teams could also be explored. Team-based implementation may improve the workplace dynamic and give HCPs more compassion for themselves, their colleagues, and their patients. Alternatively, more research is required to understand whether the team dynamic is positively affected when only a few nurses from one unit participate in the intervention or whether it is better to implement STM for the entire team. Future research should also evaluate the impact on turnover and the overall economic impact within an institution. At this time, next-step studies are under way to explore ways to disseminate this intervention on a larger scale.

In conclusion, few opportunities exist for HCPs to reflect on the impact of caregiving. STM aims to improve individuals’ well-being by bringing awareness to their emotions and providing them with skills to cope with work-related emotions. While there are workplace stresses that are not directly affected by this intervention, increasing self-awareness could improve coping with the workplace stresses that are beyond one’s control. STM provided a structured space for reflection by participants, individually and among their peers, thereby decreasing loneliness and increasing self-compassion. Both factors relate to the burnout that affects the oncology health care workforce.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Patricia Carter, PhD, RN, CNS, and Barbara Jones, PhD, MSW, FNAP, for their guidance throughout the dissertation, the oncology nurses who participated, and the songwriters who contributed.

SUPPORT

Supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Future of Nursing Scholars program; the Doctoral Degree Scholarship in Cancer Nursing (DSCN-18-06901-SCN) from the American Cancer Society; the Hogg Foundation for Mental Health: Frances Fowler Wallace Memorial for Mental Health Dissertation Award; the Central Texas Oncology Nursing Society Award; the Gordan and Mary Cain Excellence Fund for Nursing Research; The University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing; and the Mary E. Walker Dissertation Award.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Carolyn S. Phillips, Deborah L. Volker, Heather Becker

Collection and assembly of data: Carolyn S. Phillips, Kristin L. Davidson

Data analysis and interpretation: Carolyn S. Phillips, Deborah L. Volker, Heather Becker

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Storytelling Through Music: A Multidimensional Expressive Arts Intervention to Improve Emotional Well-Being of Oncology Nurses

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/site/ifc/journal-policies.html.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

No potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T, Sinsky C, et al: Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care, in NAM Perspectives. Washington, DC, National Academy of Medicine, 2017.

- 2.Gómez-Urquiza JL, Aneas-López AB, Fuente-Solana EI, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and levels of burnout among oncology nurses: A systematic review. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2016;43:E104–E120. doi: 10.1188/16.ONF.E104-E120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al: Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc 90:1600-1613, 2015 [Erratum: Mayo Clin Proc 91:276, 2016] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sinclair S, Raffin-Bouchal S, Venturato L, et al. Compassion fatigue: A meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;69:9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:475–482. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Granek L, Ben-David M, Nakash O, et al. Oncologists’ negative attitudes towards expressing emotion over patient death and burnout. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25:1607–1614. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3562-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerow L, Conejo P, Alonzo A, et al. Creating a curtain of protection: Nurses’ experiences of grief following patient death. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2010;42:122–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2010.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rushton CH, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, et al. Burnout and resilience among nurses practicing in high-intensity settings. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24:412–420. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papadatou D, Bellali T, Papazoglou I, et al. Greek nurse and physician grief as a result of caring for children dying of cancer. Pediatr Nurs. 2002;28:345–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koschwanez H, Robinson H, Beban G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of expressive writing on wound healing following bariatric surgery. Health Psychol. 2017;36:630–640. doi: 10.1037/hea0000494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bittman B, Bruhn KT, Stevens C, et al. Recreational music-making: A cost-effective group interdisciplinary strategy for reducing burnout and improving mood states in long-term care workers. Adv Mind Body Med. 2003;19:4–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barclay LJ, Skarlicki DP. Healing the wounds of organizational injustice: Examining the benefits of expressive writing. J Appl Psychol. 2009;94:511–523. doi: 10.1037/a0013451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murrock CJ, Higgins PA. The theory of music, mood and movement to improve health outcomes. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:2249–2257. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huet V, Holttum S. Art therapy-based groups for work-related stress with staff in health and social care: An exploratory study. Art Psychother. 2016;50:46–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Phillips CS, Becker H. Systematic review: Expressive arts interventions to address psychosocial stress in healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:2285–2298. doi: 10.1111/jan.14043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheval B, Mongin D, Cullati S, et al. Reciprocal relations between care-related emotional burden and sleep problems in healthcare professionals: A multicentre international cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75:647–653. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2018-105096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kearney M, Weininger R: Whole person self-care: Self-care from the inside out, in Hutchinson TA (ed): Whole Person Care: A New Paradigm for the 21st Century. New York, NY, Springer, 2011, 109-125. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledoux K. Understanding compassion fatigue: Understanding compassion. J Adv Nurs. 2015;71:2041–2050. doi: 10.1111/jan.12686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazarus R, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Papadatou D: A proposed model on health professionals grieving process. Omega 41:59-77, 2000.

- 21.Campbell DT, Stanley JC, Gage NL. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Research. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipsey M. Design Strategy. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips C, Welcer B. Songs for the soul: A program to address a nurse’s grief. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2017;21:145–146. doi: 10.1188/17.CJON.145-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): Progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care. 2007;45:S3–S11. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000258615.42478.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin CM. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management. New York, NY: Guilford; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russell DW. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66:20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karaoglu N, Pekcan S, Durduran Y, et al. A sample of paediatric residents’ loneliness-anxiety-depression-burnout and job satisfaction with probable affecting factors. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant AM, Franklin J, Langford P. The self-reflection and insight scale: A new measure of private self-consciousness. Soc Behav Personal. 2002;30:821–835. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen FF, Chen SY, Pai HC. Self-reflection and critical thinking: The influence of professional qualifications on registered nurses. Contemp Nurse. 2019;55:59–70. doi: 10.1080/10376178.2019.1590154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duarte J, Pinto-Gouveia J, Cruz B. Relationships between nurses’ empathy, self-compassion and dimensions of professional quality of life: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neff KD. The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self Ident. 2003;2:223–250. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hudnall-Stamm B: Professional quality of life: Compassion satisfaction and fatigue scales, R-IV (ProQOL). 2008. http://www.proqol.org.

- 35. Stamm B: The Concise ProQOL Manual (ed 2). Pocatello, ID, ProQOL.org, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fried EI, Bockting C, Arjadi R, et al. From loss to loneliness: The relationship between bereavement and depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2015;124:256–265. doi: 10.1037/abn0000028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers E, Polonijo AN, Carpiano RM. Getting by with a little help from friends and colleagues: Testing how residents’ social support networks affect loneliness and burnout. Can Fam Physician. 2016;62:e677–e683. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Festinger L. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raab K. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and empathy among health care professionals: A review of the literature. J Health Care Chaplain. 2014;20:95–108. doi: 10.1080/08854726.2014.913876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dobkin PL: Mindfulness and whole person care, in Hutchinson TA (ed): Whole Person Care: A New Paradigm for the 21st Century. New York, NY, Springer, 2011, pp 69-82. [Google Scholar]