Abstract

Testosterone (T) administration (TA) increases serum T and fat-free mass (FFM). Although TA-mediated increases in FFM may enhance physical performance, the data are largely equivocal, which may be due to differences in study populations, the magnitude of change in serum T and FFM, or the performance metrics. This meta-analysis explored effects of TA on serum T, FFM, and performance. Associations between increases in serum T and FFM were assessed, and whether changes in serum T or FFM, study population, or the performance metrics affected performance was determined. A systematic review of double-blind randomized trials comparing TA versus placebo on serum T, FFM, and performance was performed. Data were extracted from 20 manuscripts. Effect sizes (ESs) were assessed using Hedge’s g and a random effects model. Data are presented as ES (95% confidence interval). No significant correlation between changes in serum T and FFM was observed (P = .167). Greater increases in serum T, but not FFM, resulted in larger effects on performance. Larger increases in testosterone (7.26 [0.76-13.75]) and FFM (0.80 [0.20-1.41]) were observed in young males, but performance only improved in diseased (0.16 [0.05-0.28]) and older males (0.19 [0.10-0.29]). TA increased lower body (0.12 [0.07-0.18]), upper body (0.26 [0.11-0.40]), and handgrip (0.13 [0.04-0.22]) strength, lower body muscular endurance (0.38 [0.09-0.68]), and functional performance (0.20 [0.00-0.41]), but not lower body power or aerobic endurance. TA elicits increases in serum T and FFM in younger, older, and diseased males; however, the performance-enhancing effects of TA across studies were small, observed mostly in muscular strength and endurance, and only in older and diseased males.

Keywords: age, disease, strength, power, body composition, muscle mass

Chronic exposure to testosterone (T) concentrations below the normal range (9.5-31.8 nmol/L) [1] generally manifests in fat-free mass (FFM) loss and decrements in physical performance (ie, muscle strength and function) [2-5]. T deficiency and associated deteriorations in FFM and physical performance are common characteristics in old [4, 5] and diseased [6-11] males, but are also prevalent in healthy males exposed to stressors that suppress endogenous T synthesis, such as prolonged energy deficit, sleep deprivation, overuse, muscle unloading, injury, and spaceflight [12-14]. Thus, pharmacological restoration of normal T concentrations via exogenous T administration (TA) is now a widely accepted clinical practice in males across the population spectrum [1, 15, 16].

Several meta-analyses report that, while TA increases FFM [17-20], the performance-enhancing effects of TA are equivocal [17, 18, 21]. Failure to account for the magnitude of change in serum T following TA, the type of performance metric studied, and the study population (ie, young, old, and diseased males) may have contributed to the incongruent findings between TA, FFM, and physical performance in those meta-analyses [17-20]. For example, TA-mediated increases in serum T and FFM are dose-dependent [22, 23], such that higher T doses elicit greater increases in serum T and FFM. It has been suggested that FFM accrual underlies improvements in muscle strength and function, suggesting that the overall change in serum T following TA may not only predict changes in FFM but also physical performance. Furthermore, most research examining the effects of TA on physical performance only assess strength and power [23-30]; however, FFM accrual secondary to TA may benefit several other metrics of physical performance rarely assessed or included in meta-analyses, such as measures of muscle function, mobility, fatigue, and activities of daily living. The physiological responses to TA may also be affected by age (and health status). For example, eugonadal older men (60-75 years) receiving the same dose of T as eugonadal younger men (18-35 years) experienced greater absolute increases in serum T; however, the greater increase in serum T in older men than in younger men did not translate into greater FFM accretion and improvements in strength [23]. Collectively, these data suggest that the population studied must be accounted for when assessing the overall impact of TA on physical performance.

The primary objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to explore the effects of TA on changes in serum T, FFM, and physical performance among old, young, and diseased males. We examined associations between increases in serum T and changes in FFM following TA to determine if increases in serum T predict changes in FFM. We also aimed to determine whether changes in serum T or FFM, differences in study population, or the physical performance metrics themselves mediated the effects of TA on physical performance.

1. Materials and Methods

A. Literature search strategy

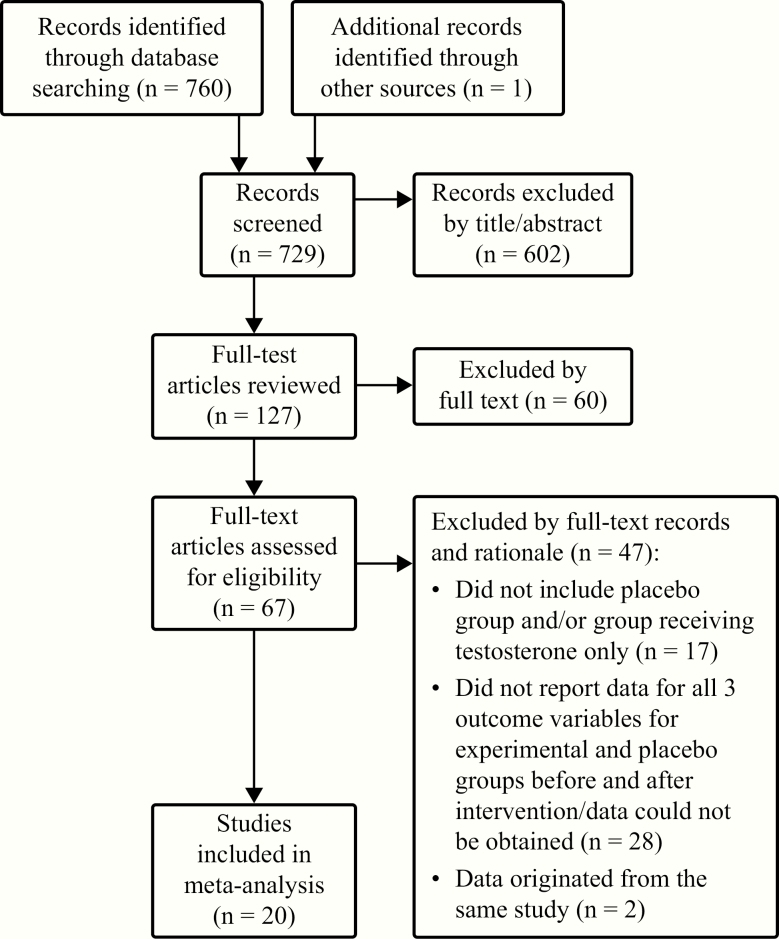

Abstracts of publications identified in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) were reviewed by A.N.V. and L.M.M. using Abstrackr (http://abstrackr.cebm.brown.edu). Literature searches took place on July 11, 2019, and were not restricted by publication date. Exact search terms are described in Table 1. All terms were included in a single search. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) search strategy and subsequent reference narrowing is described in Fig. 1 [31]. Full-text publications were reviewed independently by A.N.V. and L.M.M. for relevance and the presence of serum T, FFM, and physical performance measurements. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between researchers. The final 20 publications are included in Table 2 [24-30, 32-44].

Table 1.

Meta-analysis search terms

| Intervention terms | Outcome terms | Population terms | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Testosterone | “Body composition” | Men | Women |

| “Anabolic steroids” | “Lean body mass” | Males | Females |

| Androgens | “Fat-free mass” | Sarcopenia | Children |

| Muscle | Dynapenia | Youth | |

| “Cross-sectional area” | Hypogonadal | Adolescents | |

| Exercise | Hypogonadism | Mice | |

| Performance | “Androgen deficiency” | Rat | |

| “Physical function” | “Testosterone deficiency” | Mouse | |

| Strength | “Low testosterone” | Monkey | |

| Power | Athletes | Pig | |

| “Repetition maximum” | Bodybuilders | Rabbit | |

| Anaerobic | Powerlifters | “Erectile dysfunction” | |

| Aerobic | Castration | ||

| “Time trial” | |||

| “Time to exhaustion” | |||

| VO2max | |||

| VO2peak | |||

| Fatigue | |||

| “Aerobic capacity” | |||

| Endurance |

Search terms used in Pubmed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed) to capture relevant articles. Searches took place on 11 July 2019 and were not restricted by publication date.

Figure 1.

Selection process for manuscripts included in the meta-analysis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of studies included in the meta-analysis

| Study characteristics | T characteristics | Reported outcomes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studya | Article | Population | Comparisonb | Group | N | Type/Mode | Dose | Duration (wks) | Serum T elevation group | FFM methodc | FFM elevation group | Physical performance metric(s) |

| 1 | Bhasin et al., 1996 [24] | YNG (normal body weight, 19-40 y) | 1 | T + E | 11 | Enanthate intramuscular injection | 600 mg/wk | 10 | THI | UW | FFMHI | Lower body strength, |

| P + E | 9 | |||||||||||

| 2 | T | 10 | THI | FFMHI | Upper body strength | |||||||

| P | 10 | |||||||||||

| 2 | Bhasin et al., 2000 [25] | DIS (HIV, weight loss, low T, 18-50 y) | 3 | T + E | 11 | Enanthate intramuscular injection | 100 mg/wk | 16 | TLO | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strength,e |

| P + E | 11 | |||||||||||

| 4 | T | 15 | TLO | FFMLO | Upper body strengthe | |||||||

| P | 12 | |||||||||||

| 3 | Casaburi et al., 2004 [32] | DIS (COPD, low T, 55-80 y) |

5 6 |

T + E P + E |

11 12 |

Enanthate intramuscular injection | 100 mg/wkd | 10 |

TLO TLO |

DEXA |

FFMLO FFMHI |

Lower body strength, |

|

T P |

12 12 |

Lower body muscular endurance, | ||||||||||

| Lower body power, | ||||||||||||

| Aerobic endurancee | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Clague et al., 1999 [33] | OLD (low T, >60 y) | 7 |

T P |

7 7 |

Enanthate intramuscular injection | 200 mg/2 wk | 12 | THI | BIA | FFMLO | Lower body strengthe, |

| Lower body power, | ||||||||||||

| Handgrip, | ||||||||||||

| Functional test | ||||||||||||

| 5 | Dillon et al., 2018 [26] | YNG (head-down bed rest, 24-55 y) | 8 | T + E | 8 | Enanthate intramuscular injection | 100 mg/wk, 2 wk off between | 10 | TLO | DEXA | FFMHI | Lower body strengthe |

| P + E | 8 | |||||||||||

| 6 | dos Santos et al., 2016 [34] | DIS (CHF, low T, 18-65 y) | 9 |

T + E P + E |

8 11 |

Undecanoate intramuscular injection | 1000 mg/ onced | 16 | THI | DEXA | FFMHI | Lower body power, |

| Aerobic endurance | ||||||||||||

| 7 | Emmelot-Vonk et al., 2008 [35] | OLD (low T, 60-80 y) | 10 |

T P |

104 103 |

Undecanoate oral pills | 80 mg/2× day | 24 | TLO | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strength, |

| Handgrip, | ||||||||||||

| Functional test | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Giannoulis et al., 2006 [36] | OLD (low T, 65-80 y) | 11 |

T P |

21 16 |

Transdermal patch | 5 mg/day | 24 | TLO | DEXA | FFMHI | Lower body strengthe,, |

| Aerobic endurance, | ||||||||||||

| Handgrip | ||||||||||||

| 9 | Grinspoon et al., 1998 [37] | DIS (HIV, weight loss, low T, 18-49 y) | 12 | T | 22 | Enanthate intramuscular injection | 300 mg/3 wk | 24 | TLO | DEXA | FFMHI | Functional teste |

| P | 19 | |||||||||||

| 10 | Kenny et al., 2001 [27] | OLD (low T, >65 y) | 13 | T | 24 | Transdermal patch | 5 mg/day | 52 | TLO | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strength |

| P | 20 | |||||||||||

| 11 | Kenny et al., 2010 [38] | OLD (low T, low BMD/frailty, >60 y) | 14 |

T P |

53 46 |

Transdermal gel | 5 mg/day | 52 | TLO | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strength, |

| Lower body power, | ||||||||||||

| Handgrip, | ||||||||||||

| Functional teste | ||||||||||||

| 12 | Knapp et al., 2008 [39] | DIS (HIV, weight loss, low T, 18-60 y) | 15 |

T P |

21 27 |

Enanthate intramuscular injection | 300 mg/wk | 16 | THI | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strength, |

| Lower body muscular endurance, | ||||||||||||

| Lower body power, | ||||||||||||

| Functional teste | ||||||||||||

| 13 | Page et al., 2005 [40] | OLD (low T, >65 y) | 16 | T | 17 | Enanthate intramuscular injection | 200 mg/2 wkd | 144 | TLO | DEXA | FFMHI | Handgrip, |

| Functional test | ||||||||||||

| P | 18 | |||||||||||

| 14 | Pasiakos et al., 2019 [41] | YNG (military training, 18-39 y) | 17 |

T P |

24 26 |

Enanthate intramuscular injection | 200 mg/wk | 4 | THI | DEXA | FFMHI | Lower body strengthe, |

| Lower body muscular endurance | ||||||||||||

| 15 | Sheffield-Moore et al., 2011 [28] | OLD (low T, 60-85 y) | 18 | T | 8 | Enanthate intramuscular injection | 100 mg/wk | 20 | THI | DEXA | FFMHI | Lower body strengthe, |

| P | 8 | |||||||||||

| 19 | T | 8 | 100 mg/8 wk | THI | FFMHI | Upper body strengthe, | ||||||

| P | 8 | |||||||||||

| 16 | Snyder et al., 1999 [42] | OLD (low T, >65 y) | 20 |

T P |

50 46 |

Transdermal patch | 6 mg/dayd | 144 | THI | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strengthe, |

| Handgrip, | ||||||||||||

| Functional test | ||||||||||||

| 17 | Srinivas-Shankar et al., 2010 [43] | OLD (frail, low T, >65 y) | 21 |

T P |

130 132 |

Transdermal gel | 25–75 mg/dayd | 24 | ~ THI | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strengthe, |

| Handgrip, | ||||||||||||

| Functional teste | ||||||||||||

| 18 | Travison et al., 2011 [44] | OLD (mobility limitation, low T, >65 y) | 22 | T |

69 69 |

Transdermal gel | 50–150 mg/dayd, | 24 | THI | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strength, |

| Upper body strength, | ||||||||||||

| Lower body power, | ||||||||||||

| Handgrip, | ||||||||||||

| Functional teste | ||||||||||||

| 19 | Wittert et al., 2003 [29] | OLD (low T, >60 y) | 23 | T | 33 | Undecanoate oral pills | 40–80 mg/2× dayd, | 52 | TLO | DEXA | FFMLO | Lower body strengthe, |

| P | 25 | Handgrip | ||||||||||

| 20 | Zachwieja et al., 1999 [30] | YNG (head-down bed rest, 31-47 y) | 24 |

T P |

6 4 |

Enanthate intramuscular injection | 75 mg/day for 3 days, 200 mg/wk after | 4 | THI | DEXA | FFMHI | Lower body strengthe, |

| Upper body strengthe | ||||||||||||

BIA, bioelectrical impedance analysis; BMD, bone mineral density; CHF, chronic heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DEXA, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; DIS, “Diseased males” subgroup; FFM, fat-free mass; FFMHI, treatment group experienced higher elevations in fat-free mass than the median of all groups; FFMLO, treatment group experienced lower elevations in fat-free mass than the median of all groups; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; LBM, lean body mass; OLD, “Older males” subgroup; P, placebo; P + E, placebo and exercise training; T, testosterone; T + E, testosterone and exercise training; THI, Treatment group experienced higher elevations in serum testosterone concentrations than the median of all groups; TLO, treatment group experienced lower elevations in serum testosterone concentrations than the median of all groups; UW, underwater weighing; YNG, “Younger males” subgroup.

aIndicates individual manuscripts identified for the meta-analysis.

bIndicates each comparison extracted from individual manuscripts; each comparison was treated as a separate study.

cDenotes methods to assess FFM. When multiple methods were used in the investigation, DEXA data was preferentially used in analysis.

dIndicates that testosterone administration dosage alterations may have occurred in certain subjects.

eIndicates that multiple tests of this subgroup were assessed and each was analyzed separately in current study.

B. Study selection criteria

Studies were included if they were randomized controlled trials examining the effects of TA compared with placebo in males at least 18 years of age. Studies were required to be published in English, report serum T, FFM, and physical performance before and after the experimental intervention, and provide enough methodological information on physical performance to delineate metric type. Studies were excluded if they did not report serum T, FFM, and physical performance before and after the intervention, were observational, crossover, or not placebo-controlled. Studies were also excluded if androgens other than T were administered, T was coadministered with drugs known to affect muscle mass, strength, or sex hormone metabolism unless there were clearly defined groups that only received T, or if endogenous T production was experimentally suppressed prior to TA. Studies that duplicated data from other publications, included females, or assessed physical performance by self-report were excluded. Studies were not restricted by participant age (as long as participants were over 18 years old) but were required to report participant age and health status. If studies met all inclusion criteria but did not report data in an acceptable manner for statistical analyses, corresponding authors were contacted by e-mail to ask for additional information. The study was excluded if the data were not provided.

C. Bias analysis

A bias analysis was performed by A.N.V. and L.M.M. according to PRISMA guidelines recommended by Moher et al. [31]. Ratings of low, unclear, or high risk of selection, performance, attrition, and reporting bias were assigned to each study. Differences were resolved by discussion. The resulting risk of bias assessment is reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Risk of bias for publications included in meta-analysis

| Selection bias | Performance bias | Attrition bias | Reporting bias | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manuscript | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants/personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting |

| Bhasin et al., 1996 [24] | L | U | H | H | U | H |

| Bhasin et al., 2000 [25] | L | H | L | H | H | H |

| Casaburi et al., 2004 [32] | L | U | H | H | U | U |

| Clague et al., 1999 [33] | L | L | L | H | H | U |

| Dillon et al., 2018 [26] | L | H | U | H | H | H |

| dos Santos et al., 2016 [34] | L | L | U | H | H | U |

| Emmelot-Vonk et al., 2008 [35] | L | H | L | H | H | H |

| Giannoulis et al., 2006 [36] | L | L | L | H | H | U |

| Grinspoon et al., 1998 [37] | L | H | L | H | H | U |

| Kenny et al., 2001 [27] | L | L | L | H | H | U |

| Kenny et al., 2010 [38] | L | H | L | H | H | H |

| Knapp et al., 2008 [39] | L | H | L | H | H | U |

| Page et al., 2005 [40] | L | L | U | H | H | H |

| Pasiakos et al., 2019 [41] | L | H | L | H | H | U |

| Sheffield-Moore et al., 2011 [28] | L | L | L | H | U | U |

| Snyder et al., 1999 [42] | L | L | L | H | H | U |

| Srinivas-Shankar et al., 2010 [43] | L | H | H | H | H | U |

| Travison et al., 2011 [44] | L | H | L | H | H | H |

| Wittert et al., 2003 [29] | L | H | U | H | H | U |

| Zachwieja et al., 1999 [30] | L | L | L | H | U | U |

H, high risk; L, low risk; U: unclear.

D. Data extraction

Data were extracted from 20 manuscripts, consisting of 24 independent comparisons for serum T and FFM. Several studies included multiple physical performance outcomes; each outcome within a study was treated as an independent comparison. Serum T, FFM, and physical performance data were extracted before and after the experimental intervention. If a study measured these variables at multiple time points before and after the experimental intervention, the time points closest to the beginning and end of the intervention were used in the analysis. When a single study incorporated multiple experimental and placebo-controlled groups (eg, TA and exercise intervention versus placebo and exercise intervention and TA without exercise intervention versus placebo without exercise intervention), data were extracted from all groups receiving T and their corresponding control groups and analyzed as independent studies. In studies reporting total T, bioavailable T, and/or free T, total T data were extracted and used in our analyses, as it was the most commonly reported. Serum T values were converted to nmol/L for standardization across studies.

Studies included in this meta-analysis primarily used dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to determine FFM. As such, the term FFM was used throughout the manuscript for simplicity (some studies report lean body mass) and presumed, in part, to reflect muscle mass. For studies reporting multiple body composition methodologies, DEXA data were prioritized, extracted, and used in the analyses. If studies did not use DEXA, total body FFM or lean body mass data were extracted and analyzed, and body composition methodologies were noted in Table 2.

Each physical performance test within an individual study was treated as a separate comparison and was categorized by A.N.V. and L.M.M. into performance metric type: lower body strength, upper body strength, lower body power, lower body muscular endurance, handgrip strength, aerobic endurance, and functional tests (Tables 2 and 4). Physical performance tests not categorized into one of these metric types or tests completed at submaximal intensity (eg, normal walking speed) were excluded. Physical performance data reported in absolute values were extracted preferentially, but data reported relative to body mass were used when absolute values were not available. When performance tests of the same type were conducted at different relative intensities within an individual study, data were extracted from those conducted at the highest intensity (eg, loaded stair climb versus unloaded stair climb; 1-repetition maximum [RM] versus 3-RM). Data from isokinetic dynamometry conducted an angular velocity of 60°/second were used in the analysis when available; this angular velocity was most commonly reported among included studies. Data from unilateral physical performance tests were extracted only in the dominant limb (or the right limb when extremity dominance was not reported). In studies reporting a composite score for a physical performance type that was calculated from the combination of multiple individual performance tests, the composite score was used for analysis. Data presented only in figures or graphs were obtained using image analysis software (Image J, version 1.52a, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) by digitally measuring the height of data points and error bars and calculating relative to measured y-axis units [45].

Table 4.

Physical performance tests and corresponding metric type categories

| Physical performance type | Tests included in subgroup |

|---|---|

| Lower body strength | Isokinetic knee extension (concentric/eccentric) |

| Isokinetic knee flexion (concentric/eccentric) | |

| Isokinetic calf extension (concentric/eccentric) | |

| Isokinetic calf flexion (concentric/eccentric) | |

| Isometric knee extension | |

| Isometric knee flexion | |

| 1-RM leg press | |

| 1-RM squat | |

| 1-RM leg curl | |

| 1-RM leg extension | |

| Upper body strength | Isokinetic shoulder extension (concentric/eccentric) |

| Isokinetic shoulder flexion (concentric/eccentric) | |

| 1-RM chest press | |

| 1-RM bench press | |

| 1-RM latissimus pulldown | |

| 1-RM overhead press | |

| 1-RM arm curl | |

| 1-RM arm extension | |

| Lower body power | Leg press power |

| Cycle ergometer peak work rate during VO2max | |

| Isokinetic leg extension power | |

| Lower body muscular endurance | Leg press repetitions to failure |

| Total isokinetic work (20 knee extensions) | |

| Handgrip strength | — |

| Aerobic endurance | VO2max |

| VO2peak | |

| Constant work rate duration at % of VO2max | |

| Functional test | Unloaded stair climb |

| Loaded stair climb | |

| Unloaded walking speed | |

| Loaded walking speed | |

| 6-minute walk test | |

| Physical performance test | |

| Aggregate locomotor function test | |

| Tinnetti gait test | |

| Tinnetti balance test | |

| Lift and lower task | |

| Maximal vertical step height | |

| Timed up-and-go | |

| Sit-to-stand | |

| Get-up-and-go | |

| Supine to stand time | |

| Incremental shuttle walk | |

| Composite physical function test | |

| Short physical performance battery |

E. Statistical analysis

The difference between pre- and postintervention values for serum T, FFM, and physical performance were used in the analysis. Effect sizes (ESs) for changes in serum total T, FFM, and physical performance were determined as the standard mean difference of pre- and postintervention values divided by the pooled standard deviation at preintervention. Meta-essentials by Van Rhee [46,47] with Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to conduct the meta-analysis. To account for heterogeneity and small sample bias, random effects were applied, and ESs were generated as Hedges’ g, respectively [48]. ES values of 0.01, 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1.2, and 2.0 were considered very small, small, medium, large, very large, and huge effects, respectively [49]. ESs were coded such that positive numbers reflected increasing serum T, FFM, or physical performance measures, and negative values reflected decreasing values in comparison with placebo. For each dependent measure, an ES and the accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI) are reported. To assess heterogeneity, both the Q and I2 statistics were used to assess between-study variations in ES [48].

To assess whether discrepancies in study population, physical performance metric, or changes in serum T or FFM account for the overall variance across studies, we performed additional meta-regression and subgroup analysis. A meta-regression analysis was performed using the ES of changes in serum T as a moderator on the ES of changes in FFM to determine if increases in serum T dicate increases in FFM. To further explore the effects of increases in serum T on FFM and physical performance, each study was dichotomized into groups based on the median ES of TA on serum T as well as the median ES of TA on FFM compared to placebo into high (high T: “THI”; high FFM: “FFMHI”) and low (low T: “TLO”; low FFM: “FFMLO”). Subgroup analyses were performed to compare increases in FFM and physical performance following TA based on the median increase in serum T and FFM separately. Each study was also categorized into one of the following groups based on the population of individuals enrolled in the study: older males (>60 years; “OLD”), younger males (<60 years; “YNG”), and diseased males (not only low serum T concentrations; “DIS”) (Table 2). Subgroup analyses were performed to compare increases in serum T, FFM, and physical performance in response to TA between populations. Additional subgroup analyses were performed to compare increases in physical performance in response to TA based on the performance metric type (lower body strength, upper body strength, lower body power, lower body muscular endurance, handgrip strength, aerobic endurance, aerobic endurance, and functional tests). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

2. Results

A. Study characteristics

Of the 729 articles included in the initial literature search, 20 met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Within these studies, 24 independent comparisons were identified for serum T and FFM analysis, and 100 independent comparisons were identified for physical performance analysis. Following dichotomization of studies into groups based on the ES of increases in serum T or FFM following TA, 12 comparisons were categorized as TLO [25-27, 29, 32, 35-38, 40], and 12 comparisons were THI [24, 28, 30, 33, 34, 39, 41-44]; 12 different comparisons were categorized as FFMLO [25, 27, 29, 32, 33, 35, 38, 39, 42-44] and 12 comparisons were FFMHI [24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 37, 40, 41] (Table 2). This corresponded to 47 comparisons in TLO [25-27, 29, 32, 35, 37, 38, 40], and 53 comparisons in THI [24, 28, 30, 33, 34, 39, 41-44], as well as 60 comparisons in FFMLO [25, 27, 29, 32, 33, 35, 38, 39, 42-44] and 40 comparisons in FFMHI [24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 37, 40, 41] for physical performance analysis. Population subgroup categorization for serum T and FFM yielded 12 comparisons classified as OLD [27-29, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42-44], 5 comparisons as YNG [24, 26, 30, 41], and 7 comparisons as DIS [25, 32, 34, 37, 39] (Table 2). This corresponded to 15 comparisons in YNG [24, 26, 30, 41], 54 comparisons in OLD [27-29, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42-44], and 31 comparisons in DIS [25, 32, 34, 37, 39] for physical performance analysis. Physical performance type subgroup categorization yielded 38 comparisons classified as tests of lower body strength [24-30, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39, 41-44], 15 comparisons of upper body strength [24, 25, 28, 30, 44], 4 comparisons of lower body muscular endurance [32, 39, 41], 7 comparisons of lower body power [32-34, 38, 39, 44], 6 comparisons of aerobic endurance [32, 34, 36], 9 comparisons of handgrip strength [29, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40, 42-44], and 21 comparisons of functional tests [33, 35, 37-40, 42-44]. Study characteristics of all included articles are presented in Table 2.

B. Serum testosterone

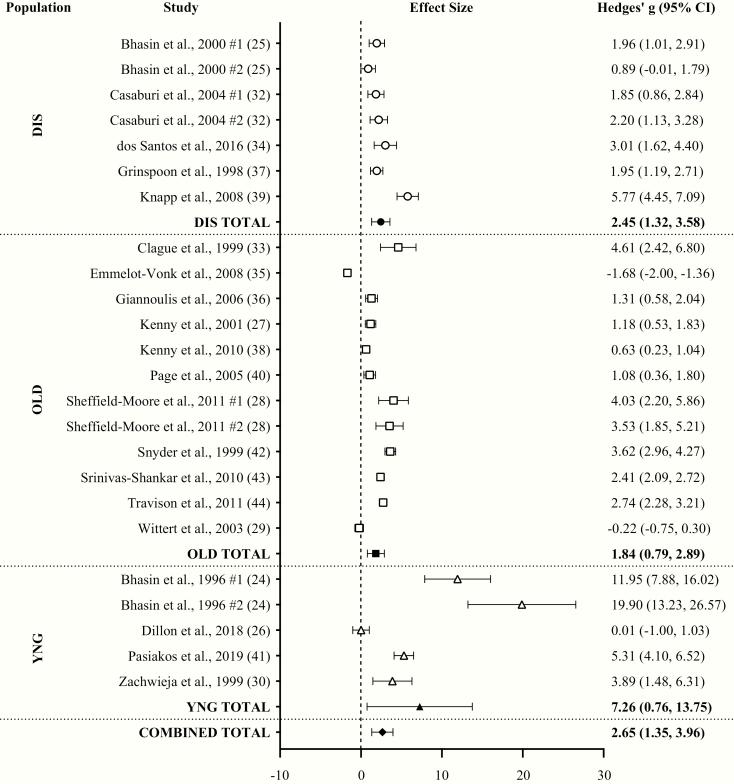

With all groups combined, TA had a huge effect (ES = 2.65; 95% CI = 1.35-3.96; P < .001) on changes in serum T compared to placebo with a high level of heterogeneity (Q = 755.88; I2 = 96.82%; P < .001) between comparisons. Egger regression analysis indicated a high level of publication bias (P < .001). TA significantly increased serum T in all populations individually. The ES of TA on serum T was huge in YNG (ES = 7.26; 95% CI = 0.76-13.75), but was very large in DIS (ES = 2.45; 95% CI = 1.32-3.58) and OLD (ES = 1.84; 95% CI = 0.79-2.89) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the effects of testosterone administration versus placebo on serum testosterone concentrations in different populations. DIS, diseased males; OLD, older males (>60 years); YNG, younger males (<60 years).

C. Fat-free mass

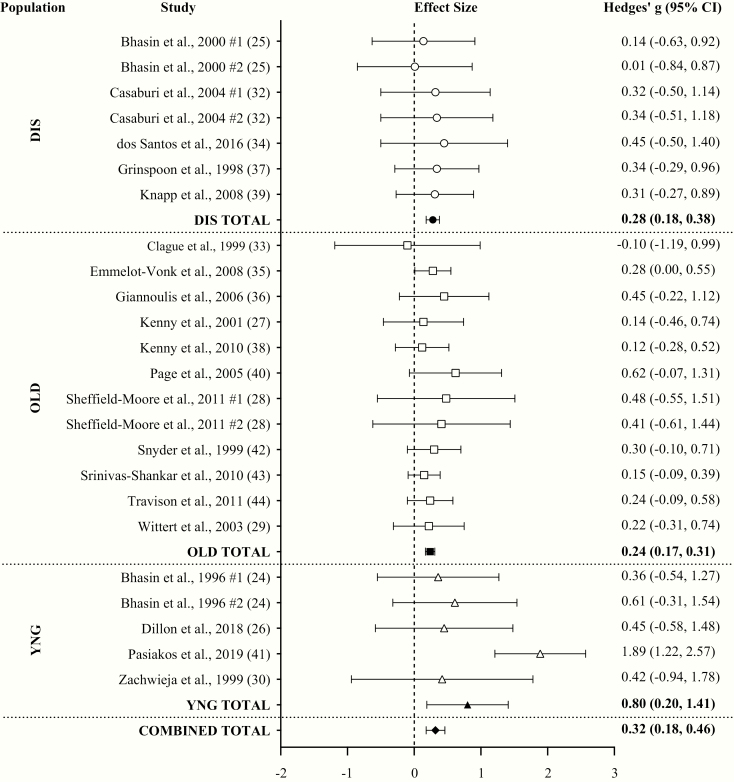

With all groups combined, TA had a small effect (ES = 0.32; 95% CI = 0.18-0.46; P < .001) on changes in FFM compared to placebo with a low level of heterogeneity (Q = 28.60; I2 = 19.59%; P = .194) between comparisons. Egger regression analysis indicated no evidence of publication bias (P = .219). Based on linear regression, the ES of increases in serum T in response to TA was not associated with the ES on FFM change when compared with placebo (P = .167). Small effects were observed for changes in FFM in both THI (ES = 0.44; 95% CI = 0.16-0.72) and TLO (ES = 0.26; 95% CI = 0.18-0.34). TA significantly increased FFM in all populations individually, but the ES of TA on FFM in YNG was large (ES = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.20-1.41) and small in DIS (ES = 0.28; 95% CI = 0.18-0.38) and OLD (ES = 0.24; 95% CI = 0.17-0.31) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the effects of testosterone administration versus placebo on fat-free mass (FFM) in different populations. DIS, diseased males; OLD, older males (>60 years); YNG, younger males (<60 years).

D. Physical performance

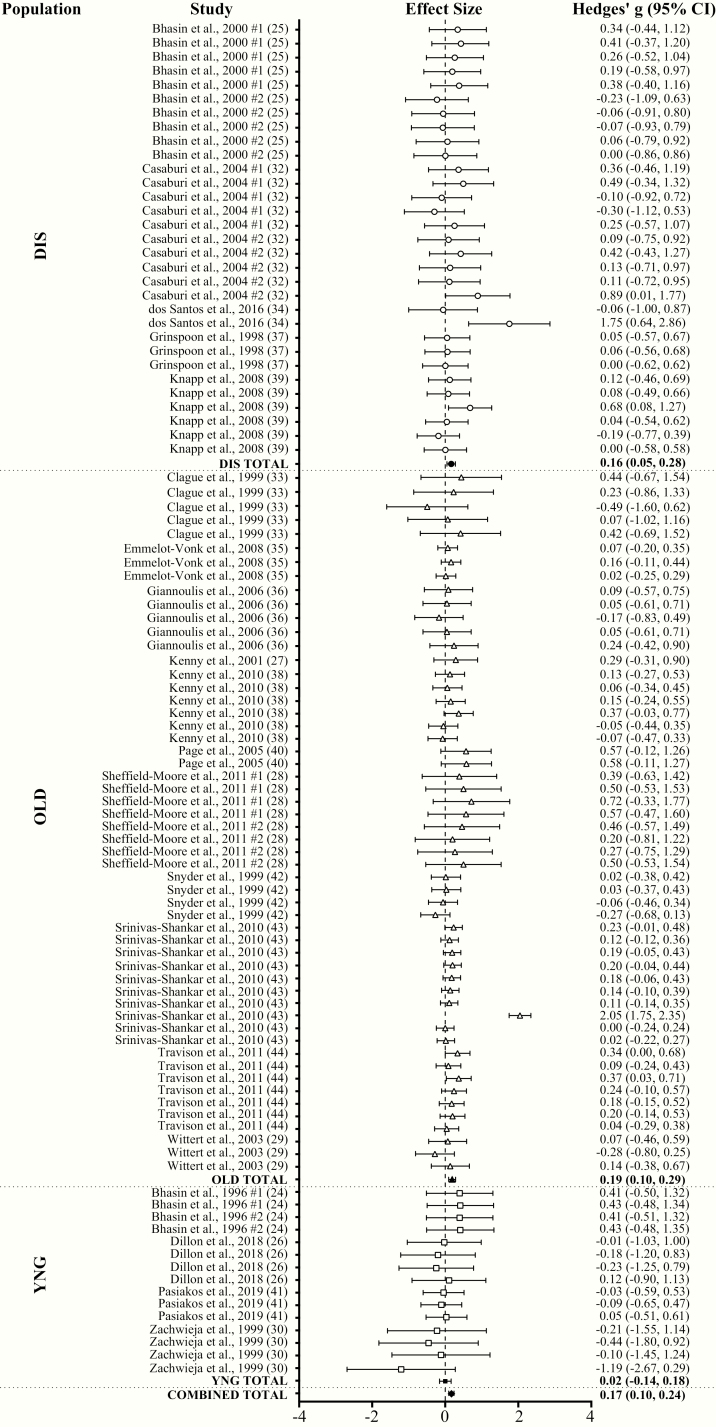

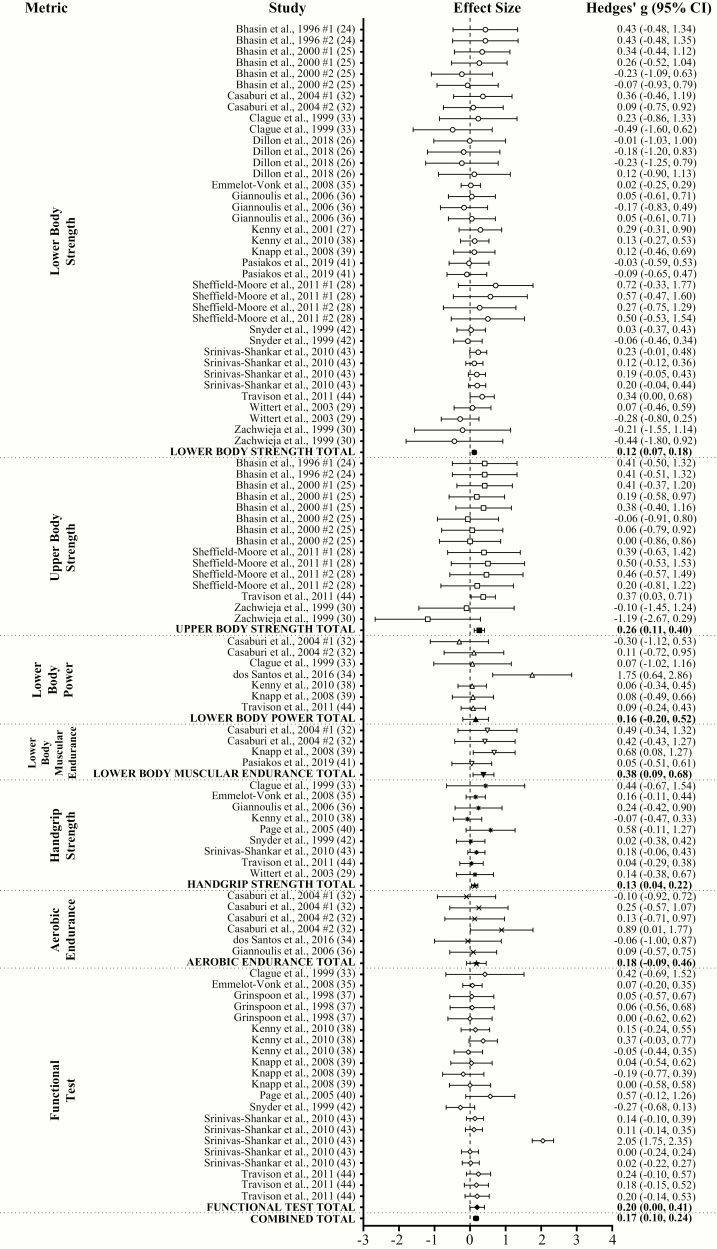

With all groups combined, TA had a very small effect (ES = 0.17; 95% CI = 0.10-0.24; P < .001) on physical performance compared to placebo with a substantial level of heterogeneity (Q = 357.05; I2 = 71.99%; P < .001) between comparisons. Egger regression analysis indicated no evidence of publication bias (P = .947). Very small (ES = 0.11; 95% CI = 0.05-0.17) and small (ES = 0.21; 95% CI = 0.09-0.32) significant effects on performance were observed in TLO and THI, respectively. Very small significant effects on performance were observed in both FFMLO (ES = 0.16; 95% CI = 0.07-0.25) and FFMHI (ES = 0.18; 95% CI = 0.07-0.29). Overall physical performance significantly increased following TA compared to placebo in DIS (ES = 0.16; 95% CI = 0.05-0.28; very small ES) and OLD (ES = 0.19; 95% CI = 0.10-0.29; very small ES), but not in YNG (ES = 0.02; 95% CI = –0.14 to 0.18) (Fig. 4A and 4B). TA significantly increased lower body (ES = 0.12; 95% CI = 0.07-0.18; very small ES), upper body (ES = 0.26; 95% CI = 0.11-0.40; small ES), and handgrip (ES = 0.13; 95% CI = 0.04-0.22; very small ES) strength, lower body muscular endurance (ES = 0.38; 95% CI = 0.09-0.68; small ES), and functional performance (ES = 0.20; 95% CI = 0.00-0.41; small ES) compared to placebo. TA had no effect on lower body power (ES = 0.16; 95% CI = –0.20 to 0.52) and aerobic endurance (ES = 0.18; 95% CI = –0.09 to 0.46) (Fig. 5A and B).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the effects of testosterone administration versus placebo on physical performance in different populations. DIS, diseased males; OLD, older males (>60 years); YNG, younger males (<60 years).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the effects of testosterone administration versus placebo on physical performance based on performance metric type.

3. Discussion

This meta-analysis demonstrates that TA had huge, small, and very small effects on changes in serum T, FFM, and physical performance compared to placebo, respectively. The ES of TA on changes in physical performance were minimally larger in THI than TLO, likely contributing little toward performance enhancement. Additionally, changes in FFM did not affect physical performance, and the ESs of TA on serum T and FFM were not significantly correlated. The ES of TA on both serum T and FFM were in larger in YNG than OLD or DIS, but physical performance was increased only in DIS and OLD and not in YNG. TA significantly improved lower body strength, upper body strength, lower body muscular endurance, handgrip strength, and functional test performance, but did not affect lower body power or aerobic endurance.

The observed effects of TA on increasing serum T and FFM align with previous individual studies and meta-analyses [17-20, 22-24, 50], but our results demonstrate that FFM accretion is not dictated by increases in serum T alone. These findings contradict studies reporting an association between TA-mediated elevations in serum T and FFM [22, 23]. The inclusion of all populations together in our meta-regression may, in part, explain our discordant results, as we observed that TA elicited larger effects on serum T and FFM in YNG than in DIS and OLD. Previous dose-response studies demonstrate that a given T dose results in greater serum T elevations in older (60-75 years) versus younger (18-35 years) eugonadal males, but the greater increases in serum T in older males did not result in greater increases in FFM [22, 23]. The higher serum T concentrations following a given T dose observed in older males [22, 23] are thought to be partially attributed to age-related decreases in T clearance rates [51]. Although these findings contradict ours, such that increases in serum T were the smallest in OLD and largest in YNG, the magnitude of the effects of TA on serum T and FFM may be dependent on participant characteristics and T formulations. In the current meta-analysis, all subjects in DIS and OLD studies had low serum T concentrations based on specific criteria for that individual study (although not part of the inclusion criteria for the current study). Age-related anabolic resistance [52-56] and differences in endocrine status (T deficient versus T sufficient)[17] may have contributed to diminished muscle mass accretion in OLD compared to YNG. Furthermore, the weekly T dose provided in most OLD and DIS studies was lower than in YNG. All studies in YNG also administered T via an intramuscular injection, whereas DIS and OLD studies used several different administration routes (transdermal patches/gels, oral, intramuscular injection). Intramuscular injections are more effective than oral or transdermal T at elevating serum T, FFM, and strength [18, 20, 57, 58]; thus, the T dose and route of administration may have contributed to greater serum T and FFM in YNG. Importantly, the magnitude of the ES of TA on serum T was substantially greater than on FFM across populations, indicating that large elevations in serum T are necessary to elicit meaningful changes in FFM.

With all groups combined, TA enhanced physical performance similarly in both FFMLO and FFMHI, suggesting factors aside from FFM (ie, presumably muscle) accretion may contribute to performance enhancement. Strength can be improved independent of muscle growth [59, 60], and muscle growth can occur without corresponding increases in strength [61, 62]. TA may also induce neural adaptations that improve motor unit recruitment and neurotransmitter synthesis that enhance strength independent of FFM accrual [63-66]. We observed that the magnitude of the effects of TA on performance are dependent on the type of performance test administered, as TA improved lower body, upper body, and handgrip strength, lower body muscular endurance, and functional performance, but did not affect lower body power or aerobic endurance. Previous meta-analyses and reviews report conflicting effects of TA on strength outcomes [17, 18, 20, 67]. Isidori et al. [17] observed improved knee extension and handgrip strength but no change in leg extension or knee flexion, and Nam et al. [67] reported increased physical function, but no change in strength. We observed a larger effect of TA on upper body than lower body strength, which conflicts with findings from a previous meta-analysis in older men receiving androgen treatment [20]. However, we restricted studies in our meta-analysis to those administering T only, whereas Ottenbacher et al. [20] included studies administering T and dihydrotestosterone. A recent meta-analysis [18] concluded that intramuscular TA results in similar magnitudes of improvement between lower and upper body strength, however transdermal TA results in small improvements in upper body strength and no change in lower body strength. We did not restrict studies based on administration route, and the inclusion of transdermal and oral TA routes in our analysis may have contributed to the smaller ES we observed in strength metrics compared to other reports [18], as well as the smaller ES we observed in lower body strength compared to upper body strength.

Few systematic reviews have investigated the effects of TA on additional physical performance parameters [67] despite the inclusion of several performance metrics in individual studies. The beneficial effects of TA on physical performance are not limited to strength outcomes. We observed that lower body muscular endurance and overall physical function are enhanced, which may improve overall quality of life. Although rodent studies have suggested that TA may increase blood capillary density [68], we observed no effect of TA on cardiorespiratory endurance. We also demonstrated that TA did not affect lower body power, which is counterintuitive considering that increases in muscular power production are largely attributed to increases in force production. Nevertheless, power is also influenced by other factors, including muscle architecture [69], physical training [70], and skeletal muscle contractile properties and neuromuscular activation [71, 72]. Previous studies demonstrated that TA in elderly males may not affect muscle architecture, despite substantial muscle hypertrophy [73]. The lack of improvements in muscular power may also help explain our findings for functional test performance, as we observed significant improvements, but the 95% CI was close to crossing zero (0.00-0.41). Studies suggest that, although performance on functional tasks are related to the strength of the muscle groups involved, power production may be more predictive of functional ability in older adults [74], and strength gains beyond a certain point may not further enhance physical function [75, 76]. Notably, all tests of functional, handgrip strength, and aerobic endurance were completed only in OLD or DIS; thus, the lack lower body power improvements may have restricted further improvements in functional tasks. Evidence also suggests that muscle quality, which is often overlooked and requires further study in the context of TA, plays a vital role in functional ability, particularly in older adults [77].

Although population-based discrepancies between elevations in serum T and FFM may be a result of differences in TA regimens, overall performance was only enhanced in DIS and OLD, despite greater increases in serum T and FFM in YNG. It is apparent that muscle mass accretion does not necessarily translate to performance improvements, especially in YNG. The T regimens typically used in clinical scenarios incorporate lower T doses administered over a prolonged period of time, aiming to gradually raise serum T while minimizing the risk of adverse events [78, 79]. The present study demonstrates that physical performance improves, specifically in OLD and DIS, even with TA regimens that are less effective at increasing serum T and FFM. To the best of our knowledge, our meta-analysis is the first to examine the effects of TA in YNG males, making it difficult to compare our results with other studies. Although speculative, these results may be a factor of the study duration in YNG, as studies in YNG were 10 weeks or less, whereas studies in OLD and DIS were generally longer. While TA-mediated increases in FFM and performance have been reported in short-term studies (≤10 weeks) [24, 26, 41], the greatest improvements often manifest over several months to a year [80]. Furthermore, the lack of performance improvements in YNG may be related to the physically-active and healthy nature of these participants at baseline. It is possible that individuals with lower baseline fitness levels, such as those in OLD and DIS, may be more likely to see physical performance benefits from TA compared to those that are healthy and physically-active.

The current investigation is not without its limitations. As with all meta-analyses, we were limited to the data available in the current literature. High levels of heterogeneity in serum T and physical performance indicate that these findings should be interpreted with caution; however, the variance in this data set can likely be attributed to differences in TA doses, administration routes, supplementation duration, and supplementation frequency between study populations. We performed meta-regression and subgroup analyses to assess if discrepancies in study population, physical performance metric, or changes in serum T or FFM accounted for the overall variance across studies, but differences in TA regimens across studies make it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. Egger regression analysis indicated that there was publication bias for serum T, but this finding may be expected because TA is known to increase serum T. However, the lack of publication bias for FFM and physical performance measures strengthens our findings, showing that TA does not consistently affect these outcomes across studies. Furthermore, several manuscripts in our literature search reported total T values, without including free T or sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) concentrations. Total T values alone may not adequately reflect the potential of TA on FFM and performance, as most circulating T is bound to SHBG, rendering it inactive. Age and health status affect SHBG concentrations [81] and therefore may change the amount of T available to perform biological activity, suggesting that measurements of bioavailable free T, albumin-bound T, or SHBG may have provided additional insight [82, 83]. In addition to age, obesity is a main determinant of T homeostasis, such that greater body fat is associated with an upregulation of the conversion of T to estradiol, reducing total T concentrations [84]. While it is possible that differences in body weight between populations may have contributed to our findings, we were unable to perform a subgroup analysis based on obesity classification because the studies included in our analysis did not directly recruit overweight or obese males. It is also possible that differences in the timing of blood sampling between studies may have impacted T concentrations due to diurnal variations in T, but we aimed to minimize these effects by examining the changes in T concentrations from pre-to postintervention. In addition, most of the studies included in the current meta-analysis used DEXA to evaluate FFM, which does not directly measure muscle mass and could be affected by the effects of TA on body water retention [78, 85]. Lastly, most studies included in this analysis used several physical performance tests in their analysis. While this allowed us to perform subgroup analyses to determine the effects of TA on different performance metrics, it prevented us from conducting a meta-regression to predict how TA-mediated increases in serum T or FFM would impact physical performance.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrates that TA in males results in huge increases in serum T, small increases in FFM, and very small increases in overall physical performance. TA-mediated increases in serum T are not related to increases in FFM, and changes in FFM may not predict physical performance improvements. Subgroup analysis between different populations revealed that TA increased serum T and FFM across all populations examined in the current study; however, physical performance was enhanced only in DIS and OLD. Finally, TA significantly improved lower body strength, upper body strength, lower body muscular endurance, handgrip strength, and functional test performance, however it did not affect lower body power or aerobic endurance. These results may be related to different TA doses, formulations, types, or study durations; therefore, future studies examining the effects of TA among different populations using similar T dosing strategies may be warranted.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Supported in part by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command and appointment to the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BIA

bioelectrical impedance analysis

- BMD

bone mineral density

- CHF

chronic heart failure

- CI

confidence interval

- DEXA

dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

- ES

effect size

- FFM

fat-free mass

- SHBG

sex hormone-binding globulin

- T

testosterone

- THI

treatment group experienced higher elevations in serum testosterone concentrations than the median of all groups

- TLO

treatment group experienced lower elevations in serum testosterone concentrations than the median of all groups

- TA

testosterone administration

- T+E

testosterone and exercise training

- U

unclear risk of bias

- UW

underwater weighing

- YNG

younger males (<60 years) subgroup

Additional Information

Disclosure Summary: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The opinions or assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Army or the Department of Defense. Any citations of commercial organizations and trade names in this report do not constitute an official Department of the Army endorsement of approval of the products or services of these organizations.

Data Availability: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(5):1715-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baumgartner RN, Waters DL, Gallagher D, Morley JE, Garry PJ. Predictors of skeletal muscle mass in elderly men and women. Mech Ageing Dev. 1999;107(2):123-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van den Beld AW, de Jong FH, Grobbee DE, Pols HA, Lamberts SW. Measures of bioavailable serum testosterone and estradiol and their relationships with muscle strength, bone density, and body composition in elderly men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(9):3276-3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matsumoto AM. Andropause: clinical implications of the decline in serum testosterone levels with aging in men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2002;57(2):M76-M99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morley JE, Perry HM 3rd. Andropause: an old concept in new clothing. Clin Geriatr Med. 2003;19(3):507-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Paepe ME, Vuletin JC, Lee MH, Rojas-Corona RR, Waxman M. Testicular atrophy in homosexual AIDS patients: an immune-mediated phenomenon? Hum Pathol. 1989;20(6):572-578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dobs AS, Dempsey MA, Ladenson PW, Polk BF. Endocrine disorders in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Am J Med. 1988;84(3 Pt 2):611-616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jankowska EA, Biel B, Majda J, et al. Anabolic deficiency in men with chronic heart failure: prevalence and detrimental impact on survival. Circulation. 2006;114(17):1829-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jankowska EA, Filippatos G, Ponikowska B, et al. Reduction in circulating testosterone relates to exercise capacity in men with chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2009;15(5):442-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sellmeyer DE, Grunfeld C. Endocrine and metabolic disturbances in human immunodeficiency virus infection and the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Endocr Rev. 1996;17(5):518-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Semple PD, Beastall GH, Watson WS, Hume R. Hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction in respiratory hypoxia. Thorax. 1981;36(8):605-609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bloomfield SA. Changes in musculoskeletal structure and function with prolonged bed rest. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(2):197-206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Convertino VA. Physiological adaptations to weightlessness: effects on exercise and work performance. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1990;18:119-166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henning PC, Park BS, Kim JS. Physiological decrements during sustained military operational stress. Mil Med. 2011;176(9):991-997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Kuo YF, et al. Screening and monitoring in men prescribed testosterone therapy in the U.S., 2001-2010. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(2):143-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baillargeon J, Urban RJ, Ottenbacher KJ, Pierson KS, Goodwin JS. Trends in androgen prescribing in the United States, 2001 to 2011. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(15):1465-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Isidori AM, Giannetta E, Greco EA, et al. Effects of testosterone on body composition, bone metabolism and serum lipid profile in middle-aged men: a meta-analysis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2005;63(3):280-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Skinner JW, Otzel DM, Bowser A, et al. Muscular responses to testosterone replacement vary by administration route: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2018;9(3):465-481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Neto WK, Gama EF, Rocha LY, et al. Effects of testosterone on lean mass gain in elderly men: systematic review with meta-analysis of controlled and randomized studies. Age (Dordr). 2015;37(1):9742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ottenbacher KJ, Ottenbacher ME, Ottenbacher AJ, Acha AA, Ostir GV. Androgen treatment and muscle strength in elderly men: a meta-analysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(11):1666-1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gruenewald DA, Matsumoto AM. Testosterone supplementation therapy for older men: potential benefits and risks. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):101-15; discussion 115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bhasin S, Woodhouse L, Casaburi R, et al. Testosterone dose-response relationships in healthy young men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2001;281(6):E1172-E1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bhasin S, Woodhouse L, Casaburi R, et al. Older men are as responsive as young men to the anabolic effects of graded doses of testosterone on the skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(2):678-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bhasin S, Storer TW, Berman N, et al. The effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on muscle size and strength in normal men. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(1):1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bhasin S, Storer TW, Javanbakht M, et al. Testosterone replacement and resistance exercise in HIV-infected men with weight loss and low testosterone levels. Jama. 2000;283(6):763-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dillon EL, Sheffield-Moore M, Durham WJ, et al. Efficacy of testosterone plus NASA exercise countermeasures during head-down bed rest. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2018;50(9):1929-1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kenny AM, Prestwood KM, Gruman CA, Marcello KM, Raisz LG. Effects of transdermal testosterone on bone and muscle in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(5):M266-M272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sheffield-Moore M, Dillon EL, Casperson SL, et al. A randomized pilot study of monthly cycled testosterone replacement or continuous testosterone replacement versus placebo in older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(11):E1831-E1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wittert GA, Chapman IM, Haren MT, Mackintosh S, Coates P, Morley JE. Oral testosterone supplementation increases muscle and decreases fat mass in healthy elderly males with low-normal gonadal status. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(7):618-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zachwieja JJ, Smith SR, Lovejoy JC, Rood JC, Windhauser MM, Bray GA. Testosterone administration preserves protein balance but not muscle strength during 28 days of bed rest. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(1):207-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Casaburi R, Bhasin S, Cosentino L, et al. Effects of testosterone and resistance training in men with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):870-878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Clague JE, Wu FC, Horan MA. Difficulties in measuring the effect of testosterone replacement therapy on muscle function in older men. Int J Androl. 1999;22(4):261-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dos Santos MR, Sayegh AL, Bacurau AV, et al. Effect of exercise training and testosterone replacement on skeletal muscle wasting in patients with heart failure with testosterone deficiency. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(5):575-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Emmelot-Vonk MH, Verhaar HJ, Nakhai Pour HR, et al. Effect of testosterone supplementation on functional mobility, cognition, and other parameters in older men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(1):39-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Giannoulis MG, Sonksen PH, Umpleby M, et al. The effects of growth hormone and/or testosterone in healthy elderly men: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(2):477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Grinspoon S, Corcoran C, Askari H, et al. Effects of androgen administration in men with the AIDS wasting syndrome. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(1):18-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kenny AM, Kleppinger A, Annis K, et al. Effects of transdermal testosterone on bone and muscle in older men with low bioavailable testosterone levels, low bone mass, and physical frailty. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(6):1134-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Knapp PE, Storer TW, Herbst KL, et al. Effects of a supraphysiological dose of testosterone on physical function, muscle performance, mood, and fatigue in men with HIV-associated weight loss. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294(6):E1135-E1143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Page ST, Amory JK, Bowman FD, et al. Exogenous testosterone (T) alone or with finasteride increases physical performance, grip strength, and lean body mass in older men with low serum T. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(3):1502-1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pasiakos SM, Berryman CE, Karl JP, et al. Effects of testosterone supplementation on body composition and lower-body muscle function during severe exercise- and diet-induced energy deficit: A proof-of-concept, single centre, randomised, double-blind, controlled trial. EBioMedicine. 2019;46:411-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Snyder PJ, Peachey H, Hannoush P, et al. Effect of testosterone treatment on body composition and muscle strength in men over 65 years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(8):2647-2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Srinivas-Shankar U, Roberts SA, Connolly MJ, et al. Effects of testosterone on muscle strength, physical function, body composition, and quality of life in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(2):639-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Travison TG, Basaria S, Storer TW, et al. Clinical meaningfulness of the changes in muscle performance and physical function associated with testosterone administration in older men with mobility limitation. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(10):1090-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tsafnat G, Glasziou P, Choong MK, Dunn A, Galgani F, Coiera E. Systematic review automation technologies. Syst Rev. 2014;3(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Van Rhee HJ, Suurmond R, Hak T. . User manual for Meta-Essentials: Workbooks for meta-analysis (Version 1.4). Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Erasmus Research Institute of Management. www.erim.eur.nl/research-support/meta-essentials.

- 47. Suurmond R, van Rhee H, Hak T. . Introduction, comparison, and validation of Meta-Essentials: A free and simple tool for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2017;8(4):537- 553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sawilowsky SS. New effect size rules of thumb. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2009;8(2):597-599. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Guo C, Gu W, Liu M, et al. Efficacy and safety of testosterone replacement therapy in men with hypogonadism: A meta-analysis study of placebo-controlled trials. Exp Ther Med. 2016;11(3):853-863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Coviello AD, Lakshman K, Mazer NA, Bhasin S. Differences in the apparent metabolic clearance rate of testosterone in young and older men with gonadotropin suppression receiving graded doses of testosterone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4669-4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Feldman HA, Longcope C, Derby CA, et al. Age trends in the level of serum testosterone and other hormones in middle-aged men: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts male aging study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):589-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ferrini RL, Barrett-Connor E. Sex hormones and age: a cross-sectional study of testosterone and estradiol and their bioavailable fractions in community-dwelling men. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(8):750-754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Laudat A, Blum L, Guéchot J, et al. Changes in systemic gonadal and adrenal steroids in asymptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-infected men: relationship with the CD4 cell counts. Eur J Endocrinol. 1995;133(4):418-424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Morley JE, Kaiser FE, Perry HM 3rd, et al. Longitudinal changes in testosterone, luteinizing hormone, and follicle-stimulating hormone in healthy older men. Metabolism. 1997;46(4):410-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Torres-Anjel MJ, Volz D, Torres MJ, Turk M, Tshikuka JG. Failure to thrive, wasting syndrome, and immunodeficiency in rabies: a hypophyseal/hypothalamic/thymic axis effect of rabies virus. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10(Suppl 4):S710-S725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Borst SE, Shuster JJ, Zou B, et al. Cardiovascular risks and elevation of serum DHT vary by route of testosterone administration: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2014;12:211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Borst SE, Yarrow JF. Injection of testosterone may be safer and more effective than transdermal administration for combating loss of muscle and bone in older men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2015;308(12):E1035-E1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dankel SJ, Counts BR, Barnett BE, Buckner SL, Abe T, Loenneke JP. Muscle adaptations following 21 consecutive days of strength test familiarization compared with traditional training. Muscle Nerve. 2017;56(2):307-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mattocks KT, Buckner SL, Jessee MB, Dankel SJ, Mouser JG, Loenneke JP. Practicing the test produces strength equivalent to higher volume training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(9):1945-1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jakobsgaard JE, Christiansen M, Sieljacks P, et al. Impact of blood flow-restricted bodyweight exercise on skeletal muscle adaptations. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Martins FM, de Paula Souza A, Nunes PRP, et al. High-intensity body weight training is comparable to combined training in changes in muscle mass, physical performance, inflammatory markers and metabolic health in postmenopausal women at high risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Exp Gerontol. 2018;107:108-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bellew JW. The effect of strength training on control of force in older men and women. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14(1):35-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Häkkinen K, Pakarinen A, Kraemer WJ, Newton RU, Alen M. Basal concentrations and acute responses of serum hormones and strength development during heavy resistance training in middle-aged and elderly men and women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55(2):B95-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Oki K, Law TD, Loucks AB, Clark BC. The effects of testosterone and insulin-like growth factor 1 on motor system form and function. Exp Gerontol. 2015;64:81-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sinha-Hikim I, Cornford M, Gaytan H, Lee ML, Bhasin S. Effects of testosterone supplementation on skeletal muscle fiber hypertrophy and satellite cells in community-dwelling older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(8):3024-3033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Nam YS, Lee G, Yun JM, Cho B. Testosterone replacement, muscle strength, and physical function. World J Mens Health. 2018;36(2):110-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Neto WK, de Assis Silva W, dos Santos da Silva A, et al. Testosterone is key to increase the muscle capillary density of old and trained rats. J Morphol Sci. 2019;36(3):182-189. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Aagaard P, Andersen JL, Dyhre-Poulsen P, et al. A mechanism for increased contractile strength of human pennate muscle in response to strength training: changes in muscle architecture. J Physiol. 2001;534(Pt. 2):613-623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Miszko TA, Cress ME, Slade JM, Covey CJ, Agrawal SK, Doerr CE. Effect of strength and power training on physical function in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(2):171-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Clark DJ, Patten C, Reid KF, Carabello RJ, Phillips EM, Fielding RA. Muscle performance and physical function are associated with voluntary rate of neuromuscular activation in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(1):115-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Reid KF, Doros G, Clark DJ, et al. Muscle power failure in mobility-limited older adults: preserved single fiber function despite lower whole muscle size, quality and rate of neuromuscular activation. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(6):2289-2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Atkinson RA, Srinivas-Shankar U, Roberts SA, et al. Effects of testosterone on skeletal muscle architecture in intermediate-frail and frail elderly men. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65(11):1215-1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Reid KF, Fielding RA. Skeletal muscle power: a critical determinant of physical functioning in older adults. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2012;40(1):4-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Buchner DM, Larson EB, Wagner EH, Koepsell TD, de Lateur BJ. Evidence for a non-linear relationship between leg strength and gait speed. Age Ageing. 1996;25(5):386-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kwon IS, Oldaker S, Schrager M, Talbot LA, Fozard JL, Metter EJ. Relationship between muscle strength and the time taken to complete a standardized walk-turn-walk test. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(9):B398-B404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McGregor RA, Cameron-Smith D, Poppitt SD. It is not just muscle mass: a review of muscle quality, composition and metabolism during ageing as determinants of muscle function and mobility in later life. Longev Healthspan. 2014;3(1):9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(2):109-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Calof OM, Singh AB, Lee ML, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone replacement in middle-aged and older men: a meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(11):1451-1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Saad F, Aversa A, Isidori AM, Zafalon L, Zitzmann M, Gooren L. Onset of effects of testosterone treatment and time span until maximum effects are achieved. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165(5):675-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Elmlinger MW, Kühnel W, Wormstall H, Döller PC. Reference intervals for testosterone, androstenedione and SHBG levels in healthy females and males from birth until old age. Clin Lab. 2005;51(11-12):625-632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bhasin S, Zhang A, Coviello A, et al. The impact of assay quality and reference ranges on clinical decision making in the diagnosis of androgen disorders. Steroids. 2008;73(13):1311-1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, Sluss PM, Raff H. Position statement: Utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(2):405-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Cohen PG. The hypogonadal-obesity cycle: role of aromatase in modulating the testosterone-estradiol shunt–a major factor in the genesis of morbid obesity. Med Hypotheses. 1999;52(1):49-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Johannsson G, Gibney J, Wolthers T, Leung KC, Ho KK. Independent and combined effects of testosterone and growth hormone on extracellular water in hypopituitary men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):3989-3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]