Abstract

Background

High-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) are integral components of the overall management of patients with multiple myeloma (MM) who are 65 years of age or younger. The emergence of oligoclonal immunoglobulin bands, immunoglobulins differing from those originally identified at diagnosis (termed clonal isotype switch, CIS), has been reported in MM patients after high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation but the clinical relevance and the correlation with immune reconstitution remains unclear.

Methods

MM patients who underwent ASCT between 2007 and 2016 were included. Percentage of NK cells, B-cells and T-cell subpopulations were measured with flow cytometry in pre- and post-ASCT bone marrow samples. CIS was defined as the appearance of a new serum monoclonal spike on SPE and immunofixation different from original heavy or light chain detected at diagnosis.

Results

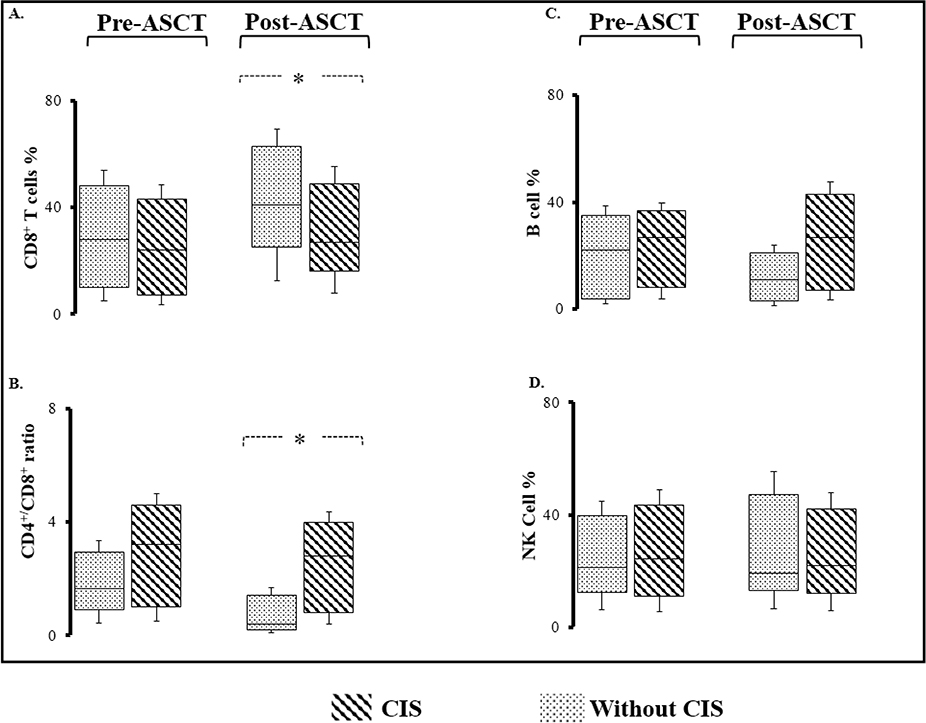

Retrospective analysis of 177 MM patients following ASCT detected CIS in 39 patients (22%). CIS post-ASCT was correlated with improved PFS (52.2 vs. 36.6, p=0.21) and OS (75.1 vs. 65.4 months, p=0.021). Patients who relapsed had an isotype different from CIS, confirming the benign nature of this phenomenon. CIS was also associated with lower CD8 T cell percentages and a greater CD4/CD8 ratio (2.8 vs. 0.2, p=0.001) compared to patients that did not demonstrate CIS, suggestive of more profound T cell immune reconstitution in this group.

Conclusion

Taken together, our data demonstrate that CIS is a benign phenomenon and correlates with reduced disease burden and enriched immune repertoire beyond the B cell compartment.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a malignancy of terminally differentiated plasma cells characterized by a decrease in both the number and functionality of immune effector cells, i.e., natural killer (NK) and T helper cells, increased immune suppressor cells, i.e., regulatory T and myeloid-derived suppressor cells, and osteoclast activation leading to tumor progression, infections and osteolytic bony lesions [1–3]. During the last two decades the advent of novel agents has led to significantly increased survival for MM patients; however, the disease remains nearly uniformly fatal through chemoresistance, the persistence of minimal residual disease (MRD) and frequent overt disease relapse. Modifications of cellular and molecular interactions in bone marrow during the course of the disease provide a permissive tumor microenvironment that favors the emergence of chemoresistant populations leading to MRD persistence [4].

High-dose melphalan (HDM) with autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) is the standard of care for MM patients and is aimed at achieving long term remission [5]. Robust post-ASCT immune-reconstitution has been shown to correlate with lower MRD and improved clinical outcomes [6]. While currently there is no specific validated immune signature to predict superior survival among MM patients, there have been reports of clonal isotype switch (CIS) post-ASCT [11]. The phenomenon has been documented in current literature under a number of different names such as oligoclonal immunoglobulins, abnormal protein bands, atypical serum immunofixation patterns, or secondary MGUS.

Prior studies have not investigated detailed bone marrow (BM) immune cell subsets before and after ASCT. We hypothesized that a comprehensive immune profiling (IP) of BM T-cell, NK-cell, B-cell, and dendritic cell (DC) subpopulations would identify immune cell phenotypes associated with prolonged PFS and OS after ASCT. Examining IP after ASCT would facilitate our understanding of immune reconstitution post-ASCT and its correlation with outcome. Strategies to enhance selected populations after ASCT could improve outcomes for MM patients.

MM cells originate after light and heavy chain switch in B lymphocytes, as suggested by the lack of mutation in the variable regions of light or heavy chains [7, 8]. Therefore, the malignant plasma cell clones almost always produce a single unique monoclonal heavy and/or light chain with constant isotype. This is represented on serum protein electrophoresis (SPEP) as an M-spike, which is considered the major disease marker followed through initial therapy and remission. CIS results in a new serum M-protein seen on SPEP, distinct from the M-protein pattern present at diagnosis, and may be associated with a good prognosis [9–11]. CIS often occurs post-ASCT or even post-induction chemotherapy [10]. Some reports suggest that MM relapse presents with the original monoclonal protein documented at diagnosis and not with the CIS protein [12]. This would suggest the transient CIS bands may represent part of the post-transplant immune reconstitution process and may even possess some anti-myeloma activity [13]. There are currently no studies that characterize the immune profile associated with CIS bands in patients undergoing ASCT. Here, we postulate that CIS occurrence correlates with a more robust reconstitution of the immune system after ASCT.

METHODS

Patients and therapies

All MM patients who underwent ASCT between 2007 and 2016 at University Hospital Cleveland Medical Center were studied. Patients that underwent allogeneic stem cell transplant were excluded. The Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study. Data collection was performed by reviewing electronic medical records and cellular therapy database. Patients who did not have flow cytometry data were excluded. Parameters included patient characteristics, induction therapy, mobilization regimen, graft characteristics including CD34+ cell dose, myeloid and erythroid progenitor cells (multi-potential colony forming unit or CFU-GM and erythroid burst-forming unit (BFU-E)). Myeloma staging was reported as International Staging System (ISS). Our institutional ASCT protocol involves peripheral blood CD34+ cells collection after mobilization with filgrastim (Amgen, CA, USA) with or without plerixafor (Sanofi Genzyme, MD, USA). Filgrastim continued throughout apheresis. BFU-E and CFU-GM assays were done on fresh collected graft for all patients. The transplant day was counted as day#0 and all days were calculated from this reference point. The conditioning regimen included amifostine 740m g/m2 intravenously (IV) on days −2 and −1 and melphalan 200 mg/m2 or 140 mg/m2 IV (i.e., based on age and organ dysfunction) on day day#−1 as previously described [14]. Daily filgastrim was administered from day#+1 and continued until neutrophil engraftment, defined by 3 consecutive days of absolute neutrophil count greater than 0.5/ml.

CIS identification

Monoclonal proteins and quantitative immunoglobulins were assessed around day+100 and with frequency of 2–8 times per year afterward. The presence of CIS was screened for by reviewing all Serum Protein Electrophoresis (SPEP), Immunofixation (IFE) and Urine Protein Electrophoresis (UPEP) and serum light chain assays pre- and post-ASCT. CIS was defined as the appearance of a new serum monoclonal spike on SPEP and IFE different from original heavy or light chain detected at diagnosis. Serum IFE was performed utilizing Sebia Hyrdrasys agarose gel electrophoresis apparatus by Sebia (Norcross, GA, USA) according to the manufacturer recommendations. Centrifuged plasma was run on alkaline agarose gels. Antibodies against IgG, IgA, IgM, kappa and lambda light chain were applied.

Immune cell subset recovery

EDTA-anticoagulated fresh bone marrow (BM) aspirate (1 mL) from each subject was immunophenotyped, using an six-color direct immunofluorescence technique previously described in detail [15], using antibodies from Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), on the BD FACSDiva platform. Percentage of NK cells (CD56(+) CD3(−) and CD16(+)CD3(−)), T-cells (CD3(+),CD56(−)), B-cells (CD19(+)), and T-cell subpopulations (CD4(+), CD8(+)),were measured with flow cytometry in pre- and post-ASCT fresh BM aspirates.

Statistical analysis

The start date for all time-dependent variables was the day of transplant (day#0). OS was calculated from day#0 to the date of death and censored at the date of last follow up. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to assess overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Two-tailed log-rank tests compared OS and PFS curves. Factors with a P-value <0.2 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis, which was performed using the Cox regression hazard model. All statistical tests were two-sided and P-value<0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All analyses were performed utilizing SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Patients’ characteristics and frequency of CIS in post-ASCT setting

The analysis included 177 MM patients who had ASCT during the study period and had available flow cytometry data. Median age was 60.7 (range 36–74) years at the time of ASCT. Median follow up of surviving patients was 38 months (range 2–101 months). CIS was detected in 39 patients (22%). Patients and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. Seventeen patients (46%) had only one new monoclonal protein, whereas 10 (25%) developed four or more monoclonal bands throughout the post-ASCT follow up period. The newly detected monoclonal proteins were <0.5 gr/dL in 34 patients (87%). The median time to occurrence of CIS was 7.1 months (range 1.9–32). The nature of CIS band heavy and light chains was mostly IgG (68%) and kappa light chain (65%), respectively.

Table 1.

Patient and Disease Characteristics. CIS occurrence correlated with monoclonal protein type and deeper therapeutic response.

| Without CIS1 (N=138) | With CIS (N=39) | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median) | 60.4 | 61.5 | 0.43 | |

| Gender (%) | 0.39 | |||

| male | 74 (54) | 21 (54) | ||

| female | 64 (46) | 18 (46) | ||

| Race (%) | 0.26 | |||

| Caucasian | 107 (78) | 29 (74) | ||

| Black | 28 (20) | 9 (23) | ||

| Others | 3 (2) | 1 (3) | ||

| Monoclonal type (%) | 0.001 | |||

| IgAκ | 10 (7) | 8 (20) | ||

| IgAL | 7 (5) | 5 (13) | ||

| IgGκ | 70 (51) | 10 (26) | ||

| IgGL | 32 (23) | 6 (15) | ||

| IgD | 1 (1) | 1 (3) | ||

| light chain | 18 (13) | 9 (23) | ||

| Hemoglobin (median, gr/dL) | 12.1 | 11.4 | 0.19 | |

| Albumin (median, gr/dL) | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.42 | |

| Pre-ASCT2 ALC3(median, × 10^9/L) | 1.09 | 1.23 | 0.37 | |

| Pre-ASCT AMC4(median, × 10^9/L) | 0.5 | 0.55 | 0.13 | |

| Pre-ASCT ALC/AMC (median) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 0.34 | |

| Plasma cell burden at diagnosis (median, %) | 40 | 50 | 0.19 | |

| Biclonal disease at diagnosis (%) | 3 (2) | 1 (3) | 0.47 | |

| High Risk Cytogenetics*(%) | 15 (17) | 6 (23) | 0.11 | |

| ISS Stage (%) | 0.21 | |||

| I | 43 (31) | 8 (21) | ||

| II | 54 (39) | 15 (38) | ||

| III | 41 (30) | 16 (41) | ||

| R-ISS Stage* (%) | 0.41 | |||

| I | 16 (17) | 5 (19) | ||

| II | 61 (67) | 16 (61) | ||

| III | 13 (14) | 3 (11) | ||

| Pre-ASCT Response (%) | 0.02 | |||

| VGPR | 32 (23) | 20 (52) | ||

| PR | 79 (57) | 6 (17) | ||

| CR | 27 (20) | 12 (31) |

CIS: Immunoglobulin Isotype Switch

ASCT: Autologous Stem Cell Transplant

ALC: Absolute Lymphocyte Count

AMC: Absolute Monocyte Count * cytogenetics was available for 90 patients without CIS and 26 patient with CIS.

Age, gender, MM risk stratification, ISS stage, or bone marrow plasma cell burden were not associated with post-ASCT CIS. The distribution of induction regimen between two cohorts is illustrated in Figure-1. Importantly, none of patients received anti-myeloma monoclonal antibodies. There was a significantly higher incidence of CIS in patients who received lenalidomide before ASCT (30.4%, vs. 11.2%, p=0.001), patients with IgA myeloma (21% vs. 7%, p=0.01) and patients who achieved VGPR pre-ASCT (52% vs. 23%, p=0.023). Also, CIS occurred more frequently in patients without suppressed un-involved immunoglobulin (92% vs 8%, p=0.001).

Figure-1.

The induction regimen distribution between patients with or without Clonal Isotype Switch (CIS) after autologous stem cell transplant. The larger portion of patients with CIS had Revlimid-continaing induction regimen before transplant (30.4%, vs. 11.2%, p=0.001). R: Revlimid (lenalidomide). V: Velcade (bortezomib). K: Kyprolis (carfilzomib). CyborD: cyclophosphamide, bortezomib and dexamethazon.

ASCT characteristics

Others have reported statistically significant difference in frequency of CIS occurrence after ASCT vs. patients who did not undergo ASCT (e.g., Mayo Clinic data: 22.7% of 458 patients who underwent ASCT vs. 1.6% of 1484 patients who did not undergo ASCT, p< 0.001) [16]. It raises the question whether the degree of immunotoxicity associated with ASCT may lead to different humoral rebound after ASCT, causing CIS. Therefore, we assessed different ASCT parameters which impact or reflect post-ASCT immunosuppression such as melphalan dose, graft composition, oral mucositis, weight loss and length of neutropenic fever period associated with ASCT (Table 2). Graft characteristics including collected Total Nucleated Cells (TNC), infused CD34+ cells, and myeloid and erythroid precursors were comparable in the CIS cohort vs. patients with no CIS (Table 2). Similarly, melphalan dose of 200 mg/m2 vs. 140 mg/m2 as the conditioning regimen (26% vs. 21%, p=0.321), as well as ASCT-associated mucositis length or severity and length of hospital admission were associated with similar frequency of CIS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Transplant Characteristics and post-transplant immunoprofiling. Clonal isotype switch (CIS) occurrence correlated with more robust lymphocyte subset recovery after transplant.

| Without CIS (N=138) | With CIS (N=39) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-ASCT Weight (median, kg) | 84.6 | 81 | 0.131 |

| Pre-ASCT BMI (median) | 30.5 | 28.4 | 0.320 |

| Weight change (median, kg) | −3.7 | −4.65 | 0.313 |

| Weight change (median, %) | −4 | −6 | 0.278 |

| Pre-ASCT1 CD4/CD8 ratio (median) | 1.3 | 3 | 0.066 |

| Pre-ASCT1 CD8 cell (median, %) | 29 | 28 | 0.430 |

| Pre-ASCT1 B cell (median, %) | 24 | 28 | 0.233 |

| Pre-ASCT1 NK cell (median, %) | 19 | 22 | 0.369 |

| Total Nucleated Cells (median, × 10 ^8/kg) | 9.92 | 9.82 | 0.485 |

| Infused CD 34+ Cell Dose (median, × 10^ 6/kg) | 4.95 | 5.16 | 0.380 |

| Myeloid Precursors (CFU-GM) (median, × 10^4) | 105.2 | 109 | 0.343 |

| Erythroid Precursors (BFU-E) (median, × 10^4) | 189.4 | 182.6 | 0.288 |

| Mucositis (%) | 63 (46) | 14 (35) | 0.256 |

| Mucositis Grade (median) | 1.70 | 1.94 | 0.323 |

| Mucositis Length (median, days) | 5 | 7.5 | 0.279 |

| Length of Hospital Admission (median, days) | 15 | 16 | 0.315 |

| Post-ASCT ALC2 (median, × 10^9/L) | 1.03 | 1.345 | 0.167 |

| Post-ASCT AMC3 (median, × 10^9/L) | 0.46 | 0.445 | 0.345 |

| Post-ASCT ALC/AMC (median) | 2.53 | 2.84 | 0.143 |

| Post-ASCT CD4/CD8 ratio (median) | 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.001 |

| Post-ASCT CD8 cell (median, %) | 43 | 28 | 0.015 |

| Post-ASCT B cell (median, %) | 16 | 32 | 0.056 |

| Post-ASCT NK cell (median, %) | 17 | 21 | 0.291 |

| Maintenance therapy (%) | 85 (61) | 23 (58) | 0.437 |

Bone marrow

ALC: Absolute Lymphocyte Count

AMC: Absolute Monocyte Count

Immune subset recovery in patients with CIS

Our group and others showed significance of peripheral lymphocytes and monocytes as prognostic factors in MM [17, 18]. There was no difference between pre- or post-ASCT peripheral absolute lymphocyte or monocyte count in patients who developed post-ASCT CIS and those that did not (Table 2). Similarly, there was no significant different in CD4, CD8, NK and B cell percentages as well as CD4/CD8 ratio in pre-ASCT bone marrow sample from patients with or without CIS. Appearance of post-ASCT CIS was associated with statistically lower CD8 T cell percentages (43% in patients without CIS vs. 28% in patients with CIS, p=0.015) and higher CD4/CD8 ratio (0.2 vs. 2.8, p=0.001) suggestive of faster T cell compartment reconstitution in this group of patients (Figure 2). Patients with CIS showed a trend toward faster B cell recovery in comparison to patients without CIS, however this difference did not reach statistical significance (16% vs. 32%, 0.056). There was no difference between NK cell percentages in post-ASCT marrow in both groups (17% vs. 21%, p=0.291).

Figure 2.

Immune subset recovery in T, B and NK cell compartment before and after autologous stem cell transplant in patients with or without Clonal Isotype Switch (CIS). A, B. Although there is no significant difference between CD8+ cell percentage or CD4+/CD8+ ratio before transplant, patients with CIS develop higher CD4+/CD8+ ratios with lower CD8+ percentages after ASCT. Asterisks represent a statistically significant difference between two groups. C, D. NK and B lymphocyte subset recovery after ASCT in patients with or without post-ASCT CIS.

Overall and Progression-free Survival

The presence of post-ASCT CIS correlated significantly with improved PFS, 52.2 vs. 36.6 months, p=0.21, and OS, 75.1 vs. 65.4 months, p=0.021 (Figure 3A and B). Age, cytogenetics, response category, presence of CIS and low LDH influenced PFS by univariate analysis. Cytogenetics, LDH and CIS presence were also significantly associated with MM response as determined by multivariate analysis. The median time between pre- and post-ASCT bone marrow (BM) was 92 days, range: 79–123 (Table 1). All patients who relapsed had an isotype different from CIS, highlighting the benign nature of this phenomenon.

Figure 3.

Outcomes of patients with or without clonal Isotype Switch (CIS). Progression free survival and overall survival comparison between two groups illustrate superior outcomes in patients with CIS.

DISCUSSION

MM is generally characterized by the abnormal production of a single heavy and/or light chain isotype by the malignant clone[19]. Here, we define the monoclonal protein signature in peripheral blood for patients who underwent ASCT and showed the CIS pattern associates with emergence of certain BM immune phenotype in the post-ASCT setting [20]. This BM immune repertoire is suggestive of a robust immune reconstitution beyond the B cell compartment. Our data are consistent with the benign nature of CIS and that CIS is not a source of relapse.. Previously reported retrospective analysis of the same phenomena from our institute by Manson et al. conducted among patients who received ASCT from 2000–2009 demonstrated significant OS benefit in patients who had delayed occurrence of a new monoclonal protein, compared to the rest of patients [20]. The lower percentage of CIS in their cohort may be due to the lower usage of novel agents in 2000–2009 compared to that in 2007–2015, [10].

Multiple groups have correlated CIS with superior survival among MM patients who are recipients of ASCT or allogeneic stem cell transplant [21, 22], but the origin of the new monoclonal bands remains largely unknown. Importantly, this phenomenon has been described under different names such as secondary MGUS [16, 20], oligoclonal or abnormal protein bands (APB) [23, 24] atypical serum immunofixation patterns (ASIPs) [25], Immunoglobolin Isotype Switch, or Immunoglobolin Class Switch [23] reflecting ambiguity around its pathogenesis. Gene sequencing of heavy chain variable region in 7 patients with post-ASCT CIS did not show clonal relation to original malignant clone idiotype [26], highlighting non-malignant B cells as the likely origin of CIS. A related question is what conditions lead to expansion of the non-malignant plasma cell clone secreting a new monoclonal protein in the post-ASCT setting. Multiple studies have demonstrated higher rates of monogammopathy correlated with immune system hyperactivation in patients with either autoimmune disease [27, 28], infections, inflammatory or allergic disorders [29] and after myeloablative regimens in recipients of allograft when humoral reconstitution occurs in a clonally deregulated pattern [30]. Our finding that CIS is associated with an expanded T and possibly B cell compartment supports the hypothesis that CIS is the result of robust immune reconstitution post-ASCT. Furthermore, our results confirm other reports of increased polyclonal B cell content in post-ASCT bone marrow as a predictor of better survival [31].

The non-malignant nature of CIS is supported by our result, as well as others [32], when all the disease relapses were different than CIS heavy and/or light chain in nature and CIS decreased or disappeared upon relapse. This finding can suggest a clonal competition between the malignant clone and the non-malignant clone responsible for CIS. In corollary, the European Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) criteria indicate that the presence of a different monoclonal protein in absence of the original MM protein should be considered complete response [32]. We preferred to use CIS terminology instead of secondary MGUS to differentiate this monoclonal gammopathy from the more commonly known MGUS as a pre-malignant condition [33].

Our data should be interpreted in the context of new knowledge of clonal tides in sequential relapses associated with emerging different clones over time, as the result of Darwinian mutational branching, as well as other reports of monoclonal protein signature in peripheral blood of MM patients [34]. The interplay between the clone responsible for CIS and emerging new and hybrid malignant clones remains to be defined. Campel et al. showed that smaller clones, represented as an accessory monoclonal protein band, i.e., 10–20 times smaller than major monoclonal band, are detected at diagnosis of biclonal MM.

There is an inherent limitation to the methodology of our study and similar studies that rely on SPE/IFE to detect the CIS. These studies are mostly able to identify the clones that make a different heavy or light chain than the original MM clone; therefore new clones that secrete the same M protein as the original MM clone are somewhat missing [16]. The majority of CIS occurs with clones that make IgG and Kappa as in our cohort and reported by others [20, 22, 35];, on the other hand IgG Kappa is the most frequent nature of malignant clone responsible for bulk of the initial disease for newly diagnosed MM. Therefore one may hypothesize that a slow and small rise in IgG Kappa M-protein post-ASCT in an asymptomatic patient with initial IgG Kappa disease may represent CIS which correlates with long remission and survival, rather than early post-ASCT relapse, which would denote clinically high-risk disease [36]. Future studies that will measure disease burden with Next Generation Sequencing can overcome the limitations of SPEP. Furthermore, these finding should be taken into account by response-adaptive strategies utilizing MRD testing to gauge anti-myeloma therapy aiming at curative measure[34, 37]. Overall, CIS is not an uncommon phenomenon post ASCT in MM patients and practitioners should be aware to not be mistaken with biochemical relapse.

Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies such as daratumumab and elotuzuma are emerging as new element of anti-myeloma therapy and they can be detected as a low IgG kappa monoclonal protein in SPEP up to 6 months after therapy [38]. Therefore, When interpreting newly identifed monoclonal proteins in treated MM patients, CIS should not be confused with low level monoclonal bands caused by these antibodies. The new assays to mitigate the interference from these antibodies can tease out CIS from pharmacologic monoclonal protein [39].

Here, we showed that CIS occurrence correlates with a low disease volume and enriched immune repertoire. This setting can be optimal to modulation by upcoming immune-based therapies, such as checkpoint inhibitors, for further suppression or potential elimination of MRD in the post-ASCT setting; therefore CIS may serve as an immune biomarker that helps to define a subset of patients most likely to benefit from immunotherapies [17]. Also efforts to better understand how specific immune subpopulations trigger and regulate the immune response to tumors may improve long-term control of MM. Further research to define whether there is an underlying anti-tumor effect of CIS is also needed.

CLINICAL POINTS.

Clonal Isotype Switch associated with better immune reconstitution after transplant in patients with Multiple Myeloma.

Clonal Isotype Switch correlated with superior progression free survival after transplant in patients with Multiple Myeloma.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

E.Malek was supported in part by institutional K12 Paul Calabresi Career Development Award. O. Landgren was supported in part by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Core Grant (P30 CA008748) from the National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD, USA.

AUTHOR DISCLOSURES: J. Driscoll: Research Funding from Takeda/Millennium, Onyx/Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Sanofi Oncology. E. Malek: Advisory board/Consultant/Speaker: Takeda, Celgene, Sanofi, Amgen, Janssen

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERNCES

- 1.An G, et al. , Osteoclasts promote immune suppressive microenvironment in multiple myeloma: therapeutic implication. Blood, 2016. 128(12): p. 1590–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broder S, et al. , Impaired synthesis of polyclonal (non-paraprotein) immunoglobulins by circulating lymphocytes from patients with multiple myeloma: Role of suppressor cells. New England Journal of Medicine, 1975. 293(18): p. 887–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malek E, et al. , Myeloid-derived suppressor cells: The green light for myeloma immune escape. Blood reviews, 2016. 30(5): p. 341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rawstron AC, et al. , Minimal residual disease assessed by multiparameter flow cytometry in multiple myeloma: impact on outcome in the Medical Research Council Myeloma IX Study. Journal of clinical oncology, 2013. 31(20): p. 2540–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Attal M, et al. , Lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone with transplantation for myeloma. New England Journal of Medicine, 2017. 376(14): p. 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho CM, et al. , Immune signatures associated with improved progression-free and overall survival for myeloma patients treated with AHSCT. Blood Advances, 2017. 1(15): p. 1056–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kosmas C, et al. , Origin and diversification of the clonogenic cell in multiple myeloma: lessons from the immunoglobulin repertoire. Leukemia, 2000. 14(10): p. 1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.González D, et al. , Immunoglobulin gene rearrangements and the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Blood, 2007. 110(9): p. 3112–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sucak G, et al. , Abnormal protein bands in patients with multiple myeloma after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation: does it have a prognostic significance? Hematological oncology, 2010. 28(4): p. 180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Larrea CF, et al. , Emergence of oligoclonal bands in patients with multiple myeloma in complete remission after induction chemotherapy: association with the use of novel agents. Haematologica, 2011. 96(1): p. 171–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alejandre ME, et al. , Oligoclonal bands and immunoglobulin isotype switch during monitoring of patients with multiple myeloma and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation: a 16-year experience. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine, 2010. 48(5): p. 727–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maisnar V, et al. , Isotype class switching after transplantation in multiple myeloma. Neoplasma, 2007. 54(3): p. 225–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rahlff J, et al. , Antigen-specificity of oligoclonal abnormal protein bands in multiple myeloma after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy, 2012. 61(10): p. 1639–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malek E, et al. , Amifostine reduces gastro-intestinal toxicity after autologous transplantation for multiple myeloma. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 2018: p. 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rawstron AC, et al. , Report of the European Myeloma Network on multiparametric flow cytometry in multiple myeloma and related disorders. haematologica, 2008. 93(3): p. 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wadhera RK, et al. , Incidence, clinical course, and prognosis of secondary monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood, 2011. 118(11): p. 2985–2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dosani T, et al. , Significance of the absolute lymphocyte/monocyte ratio as a prognostic immune biomarker in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Blood cancer journal, 2017. 7(6): p. e579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porrata LF, et al. , Early lymphocyte recovery predicts superior survival after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood, 2001. 98(3): p. 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campbell JP, et al. , Response comparison of multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance to the same anti-myeloma therapy: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet Haematology, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manson G, et al. , Secondary MGUS after autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation in plasma cell myeloma: a matter of undetermined significance. Bone marrow transplantation, 2012. 47(9): p. 1212–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitz MF, et al. , Secondary monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance after allogeneic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma. haematologica, 2014. 99(12): p. 1846–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zou D, et al. , Secondary monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance is frequently associated with high response rate and superior survival in patients with plasma cell dyscrasias. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 2014. 20(3): p. 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zent C, et al. , Oligoclonal protein bands and Ig isotype switching in multiple myeloma treated with high-dose therapy and hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood, 1998. 91(9): p. 3518–3523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Larrea CF, et al. , Abnormal serum free light chain ratio in patients with multiple myeloma in complete remission has strong association with the presence of oligoclonal bands: implications for stringent complete remission definition. Blood, 2009. 114(24): p. 4954–4956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mark T, et al. , Atypical serum immunofixation patterns frequently emerge in immunomodulatory therapy and are associated with a high degree of response in multiple myeloma. British journal of haematology, 2008. 143(5): p. 654–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guikema JE, et al. , Multiple myeloma related cells in patients undergoing autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. British journal of haematology, 1999. 104(4): p. 748–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krumbholz M, et al. , B cells and antibodies in multiple sclerosis pathogenesis and therapy. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2012. 8(11): p. 613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brito-Zerón P, et al. , Monoclonal gammopathy related to Sjögren syndrome: a key marker of disease prognosis and outcomes. Journal of autoimmunity, 2012. 39(1): p. 4348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown LM, et al. , Risk of multiple myeloma and monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance among white and black male United States veterans with prior autoimmune, infectious, inflammatory, and allergic disorders. Blood, 2008. 111(7): p. 3388–3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pageaux G-P, et al. , Prevalence of monoclonal immunoglobulins after liver transplantation: relationship with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Transplantation, 1998. 65(3): p. 397–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byrne E, et al. , Excess bone marrow B-cells in patients with multiple myeloma achieving complete remission following autologous stem cell transplantation is a biomarker for improved survival. British journal of haematology, 2011. 155(4): p. 509–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.BladÉ J, et al. , Criteria for evaluating disease response and progression in patients with multiple myeloma treated by high-dose therapy and haemopoietic stem cell transplantation. British journal of haematology, 1998. 102(5): p. 1115–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landgren O, et al. , Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS) consistently precedes multiple myeloma: a prospective study. Blood, 2009. 113(22): p. 5412–5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landgren O and Giralt S, MRD-driven treatment paradigm for newly diagnosed transplant eligible multiple myeloma patients. Bone marrow transplantation, 2016. 51(7): p. 913–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fujisawa M, et al. , Oligoclonal bands in patients with multiple myeloma: Its emergence per se could not be translated to improved survival. Cancer science, 2014. 105(11): p. 1442–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caillon H, et al. , Difficulties in immunofixation analysis: a concordance study on the IFM 2007–02 trial. Blood cancer journal, 2013. 3(10): p. e154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mailankody S, et al. , Minimal residual disease in multiple myeloma: bringing the bench to the bedside. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 2015. 12(5): p. 286–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beck R, et al. , 18 Investigating the Pattern of Detection of Therapeutic Monoclonal Antibodies Elotuzumab and Daratumumab by Routine Serum Protein Electrophoresis and Immunofixation in Patients with Myeloma. American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 2018. 149(suppl_1): p. S7–S8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCudden C, et al. , Assessing clinical response in multiple myeloma (MM) patients treated with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs): validation of a daratumumab IFE reflex assay (DIRA) to distinguish malignant M-protein from therapeutic antibody. J Clin Oncol, 2015. 33(15 Suppl): p. 8590. [Google Scholar]