Abstract

The reimbursement of immune checkpoint inhibitors is challenging. Funding these technologies involves the careful balance between awarding innovation and ensuring affordability as increases in drug spending compete directly with other health care and social expenditure. This narrative review examines the recommendations of 2 health technology assessment agencies—the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee and the British National Institute of Clinical Excellence—to determine the factors that contribute to the approval and rejection of immune checkpoint inhibitors as well as the use of manage entry schemes and risk management strategies to control expenditure. Reimbursement decisions from 6 immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs (ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, durvalumab, atezolizumab, avelumab) covering 10 different cancers were examined. The extrapolation of survival beyond the clinical trial and lack of head‐to‐head evidence are some of the main issues relating to cost effectiveness. Payers managed financial risks using different mechanisms such as risk share agreements and financial caps. This review of the reimbursement decisions and subsequent financial impact in Australia and the UK suggests budgets for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy have been well managed so far. Through risk agreements and managed entry programmes, the example of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies illustrates that industry and payers can effectively collaborate to ensure that innovative, but expensive, drugs can be made readily available to patients.

Keywords: cancer, health economics, immunotherapy, pharmacoeconomics

1. INTRODUCTION

The reimbursement of new high‐cost innovative medicines is particularly challenging. Costly to develop, funding these technologies involves the careful balance between awarding innovation and ensuring affordability as increases in drug spending compete directly with other health care and social expenditure.

The advent of immunotherapy drugs, such as immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy, illustrates these issues. Marked as a paradigm shift in cancer treatment, ICI therapy offers the possibility of long‐term survival among cancer patients. 1 Ipilimumab was the first ICI therapy to gain Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency regulatory approval in 2011. 2 Australia 3 and the UK 4 undertook the first reimbursement evaluations the same year with approvals for funding granted the following year. 5 , 6 However, the initial costs of these drugs have caused anxiety among health care providers, patients, payers and researchers, as countries have to balance affordability and timely access to these drugs. 7 , 8

To meet this challenge, reimbursement agencies have developed several approaches to ensure appropriate access whilst managing the financial risk to health care budgets. Health technology assessment (HTA) is now being used almost ubiquitously to assist health care providers and payers decide whether new therapies, such as ICI medicines represent good value for money. 8 HTA is the systematic evaluation of direct and indirect effects of health technology, 9 and the subfield of health economic modelling is an integrated part of decision analysis when assessing the cost effectiveness of these drugs. 10 This principle was first implemented in Australia in 1992 as a mandatory part of evaluations of pharmaceutical products by Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC). The use of HTA has been broadened to include medical devices with the issue of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines in 2001 in the UK. 11

As part of the HTA process, a variety of managed entry schemes have been developed to improve affordability. Outcome‐based schemes include schemes that require conditional treatment rules and coverage with evidence development. An example is avelumab for the treatment of Merkel cell carcinoma. The UK NICE approved avelumab for reimbursement under the condition that the sponsor report additional survival data as the initial data only consisted of a small number of patients with short follow‐up. 12 , 13 Nonoutcome‐based schemes refer to price volume agreements, dosing caps, discounts and hypothecated budgets. A discount in the form of a rebate is common. 14 These are sometimes referred as special price arrangements in Australia. 15

This paper sought to examine the recommendations of 2 HTA agencies (PBAC and NICE) to determine the factors that contribute to the approval and rejection of ICIs. The paper also explores the use of managed entry schemes and risk management strategies to control expenditure.

2. METHODS

A narrative review was undertaken of all published funding decisions by the Australian PBAC and the NICE in the UK regarding ICIs. These HTA agencies were chosen because they were among the first to appraise ICI therapies. A search was conducted among public summary documents issued by the PBAC and technology appraisal guidance reports issued by NICE that involved ICIs in https://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd and https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance, respectively. Records from September 2009 (which was 12 months prior to the date of the first published phase III trial of an ICI agent) to 28 October 2019 were reviewed. Where available, listing and cost data were retrieved from government websites.

3. RESULTS

Six ICI drugs (ipilimumab, pembrolizumab, nivolumab, durvalumab, atezolizumab, avelumab) were found to have been considered for reimbursement. In total, 29 guidance documents have been issued by NICE across 9 different tumour types. Only 1 of the guidance documents did not recommend reimbursement 16 ; however, another ICI drug is available for that indication. 17 There were 46 public summary documents published by the PBAC covering 10 different cancers. Of the 46 PBAC reimbursement submissions 29 were rejections and the remaining 17 resulted in a recommendation to subsidise the drug on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS: a programme of the Australian Government that provides subsidised prescription medicines; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor drugs considered by British National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) and Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC)

| Drug | NICE | PBAC |

|---|---|---|

| Ipilimumab | GBP 3750/50 mg 13 | AUD 16 962.82/120 mg 18 |

| • metastatic melanoma | • *Dec 2012, 6 *Jul 2014 14 | • ^July 2011, 3 ^Mar 2012, 19 *Nov 2012 5 |

| Pembrolizumab | GBP 1315/50 mg 20 | AUD 9005.06/200 mg 18 |

| • metastatic melanoma | • *Oct 2015 21 , 22 | • *Mar 2015 23 |

| • adjuvant melanoma | • *Dec 2018 24 | • ^Nov 2018, 25 ^Jul 2019 26 |

| • metastatic colorectal cancer | No assessment | • ^Mar 2019 27 |

| • relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B‐cell lymphoma | No assessment | • ^Nov 2018 28 |

| • relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin's lymphoma | • *Sep 2018 29 | • *Aug 2017 30 |

| • squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck | • *Apr 2018 17 , *Jun 2018 31 | • ^Jul 2018 32 |

| • metastatic urothelial cancer | No assessment | • ^Nov 2017, 33 *Jul 2018 34 |

| • nonsmall cell lung cancer | • *Jan 2017, 35 *Jun 2017, 36 *Jul 2018, 20 *Jan 2019 37 | • ^Nov 2016, 38 ^Mar 2017, 39 ^Nov 2017, 40 ^Mar 2018, 41 *Jul 2018 42 |

| Pembrolizumab + chemotherapy | ||

| • nonsmall cell lung cancer | • *Sep 2019 43 | • ^Nov 2018, 44 ^Jul 2019 45 |

| Nivolumab | GBP 439/40 mg 13 | AUD 10 053.46/480 mg 18 |

| • metastatic melanoma | • *Feb 2016 46 | • ^Jul 2015, 47 *Nov 2015 48 |

| • nonsmall cell lung cancer | • *Nov 2017 49 , 50 | • ^Mar 2016, 51 ^Nov 2016, 52 *Mar 2017 53 |

| • renal cell carcinoma | • *Nov 2016 54 | • ^Jul 2016, 55 ^Nov 2016, 56 *Mar 2017 57 |

| • squamous cell carcinoma of the head or neck | • *Nov 2017 58 | • ^Nov 2017, 59 *Mar 2018 60 |

| • adjuvant melanoma | • *Jan 2019 61 | • ^Jul 2018, 62 ^Mar 2019, 63 *Nov 2019 64 |

| • relapsed/refractory classical Hodgkin's lymphoma | • *Jul 2017 65 | No assessment |

| • metastatic urothelial cancer | • ^Jul 2018 16 | No assessment |

| Durvalumab | GBP 592/120 mg 66 | Not reimbursed in Australia |

| • nonsmall cell lung cancer | • *May 2019 66 | • ^Nov 2018, 67 ^Jul 2019, 68 *Nov 2019 64 |

| • metastatic urothelial cancer | No assessment | • ^Jul 2019 69 |

| Nivolumab + ipilimumab | ||

| • nonsmall cell lung cancer | • *Jul 2016 13 | • Nov 2015, 70 Mar 2017, 71 Jul 2018 72 |

| • renal cell carcinoma | • *May 2019 73 | • Jul 2018, 74 Nov 2018 75 |

| Atezolizumab | GBP 3807.69/1200 mg 76 | AUD 7561.36/1200 mg 18 |

| • nonsmall cell lung cancer | • *May 2018 76 | • *Nov 2017 77 |

| • metastatic urothelial cancer | • *Jun 2018, 78 *Jul 2018 79 | No assessment |

| • small cell lung cancer | No assessment | • ^Jul 2019, 80 *Nov 2019 64 |

| Atezolizumab + bevacizumab | ||

| • nonsmall cell lung cancer | • *Jun 2019 81 | • *Mar 2019 82 |

| Avelumab | GBP 768/200 mg 12 | AUD 8229.22/1200 mg 18 |

| • metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma | • *Apr 2018 12 | • *Jul 2018 83 |

: not recommended,

: recommended.

During this period, ICI drugs have also been considered in combination (such as nivolumab + ipilimumab), and in combination with other agents (such as pembrolizumab + chemotherapy and atezolizumab + bevacizumab). Most of the target tumours were stage IV metastatic disease, but more recent applications involved adjuvant therapy for stage III nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

The first‐time rejection rate is 76.2% (see Figure 1). Most of the rejections in Australia were followed up with subsequent resubmissions. However, for 2 tumour types, namely metastatic colorectal cancer and relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B‐cell lymphoma, this has not occurred yet and as of Q1, 2020 no ICI drug is available for these indications in Australia.

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of first‐time rejections in Australia. ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor

Australian public summary documents report whether or not reimbursement listing was recommended by the PBAC, while NICE technical appraisal guidance reports 1 of the following outcomes:

do not recommend

recommend only when the company provides the therapy in line with the commercial access agreement with NHS England 21

recommend for use within the Cancer Drugs Fund only if the conditions in the managed access agreement for the therapy are followed 12

recommend when the company provides the therapy with the discount agreed on in the patient access scheme. 13

It is important to note that all therapies were subject to special pricing arrangements in the form of either a rebate and/or a financial cap.

3.1. Factors relating to cost‐effectiveness

Ipilimumab was the first ICI to be considered for reimbursement by the PBAC (July 2011) 3 and NICE (December 2012) 6 for metastatic melanoma. The dosing regimen for ipilimumab is 4 infusions over a 9‐week period 84 at a cost of approximate GBP 58 500. Both reimbursement agencies considered that the length of follow‐up in the pivotal clinical trial did not provide robust evidence of the overall survival gain beyond the length of the trial, therefore extrapolation of the clinical benefit was necessary in order to demonstrate cost effectiveness. However, the way the 2 agencies addressed the gap in evidence differed. After 2 further submissions 5 , 19 the PBAC mandated an outcome‐based risk share agreement to assess whether trial efficacy translated into real‐world effectiveness. 5 As part of the agreement, the PBAC reassessed ipilimumab in 2016 using real‐world data, which confirmed the initial estimate of cost‐effective. 85 Similarly, NICE was unable to reliably quantify the long‐term survival benefit even after real‐world data in the form of register data from the USA was presented by the sponsor during the consultation of the evaluation to fill the data gap. NICE decided that a simple discount was to be applied to the list price of ipilimumab to make it cost‐effective, i.e. the price reduction mitigated the uncertainty in the estimated cost‐effectiveness.

The funding of ipilimumab in Australia is a good example of industry and Government working together, via a risk‐share agreement to allow early reimbursement as further evidence was collected. However, the sponsor may delay the reimbursement application and opt to wait for longer‐term data to be available. This was the case for second‐line treatment of renal cell carcinoma with nivolumab 56 and for the combination treatment of nivolumab and ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma. 72

Choice of extrapolation of survival data is a common source of uncertainty in cost‐effectiveness assessments of ICI drugs. 86 For example, in guidance document TA519 when considering pembrolizumab, NICE found that using the Gompertz curve for extrapolation assumed that no patient could reside in the postprogressive health state after year 6. 17 This meant that patients could only move from preprogression to death, which is not in accord with real‐world observations.

Lack of head‐to‐head evidence is another common stumbling block for demonstrating cost‐effectiveness for ICI therapies. Pembrolizumab sought reimbursement for NSCLC in 2016 in Australia, but the PBAC concluded that the magnitude of the gain in effectiveness over pemetrexed was unclear due to the need to conduct an indirect comparison. 37 Moreover, the PBAC did not find pembrolizumab cost‐effective in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck due to uncertainty related to the indirect comparison (in addition to low unmet clinical need). 31 By contrast, high unmet need was the driver behind pembrolizumab getting first‐time approval for metastatic melanoma despite the absence of head to head data. 23

3.2. Managing financial risks

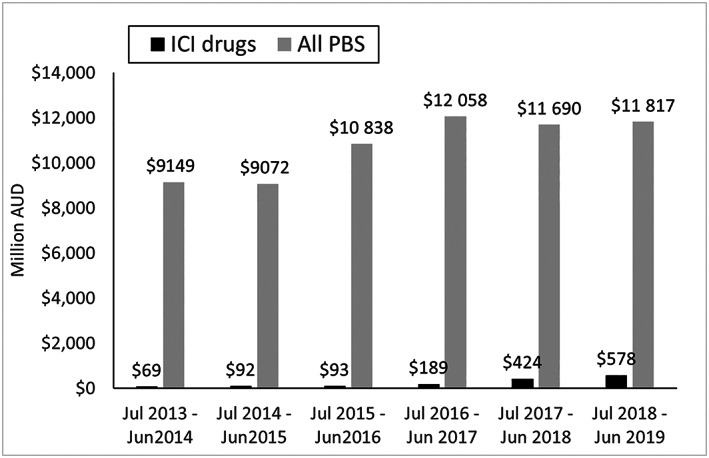

The approach to funding ICI therapies differs between Australia and England/Wales. ICI therapies in Australia are funded through a scheme called Efficient Funding of Chemotherapy (EFC)— Section 100 Arrangements which is a part of the Australian PBS. 87 The total cost of the PBS is uncapped. 88 The total costs for ICI therapies across all tumour types was approximately AUD 578 million (approx. GBP 306.5 million or USD 394.9 million) for the financial year ending June 2019 (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Cost of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapies and total cost of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia 89 , 90 , 91 , 92 , 93 , 94

The total expenditure of the Australian PBS was AUD 11.8 billion for the financial year ending in June 2019. 94 Therefore, it appears that ICI drugs accounted for approximately 5% of the overall PBS expenditure. To put this into perspective, the combined costs of adalimumab (AUD 320.4 million 93 ) and aflibercept (AUD 304.2 million 93 ) amounted to AUD 46 million more than the whole class of ICI therapies, although as can been seen in Figure 2, expenditure on ICI drugs is increasing. It should be noted that these numbers are only indicative, as each therapy has its own special pricing arrangement and rebate, which are commercial in confidence.

England and Wales fund ICI therapies through the Cancer Drug Fund, which operates with a fixed budget. 95 A recent review found that they kept the spending for the Cancer Drug Fund within the GBP 340 million a year budget. 96

Every ICI therapy had a special pricing arrangement on the Australian PBS or there was a requirement to provide the drug according to a commercial/patient/managed access agreement or scheme with NICE. One interpretation of this is that the companies had to offer a rebate of the public listed price of the ICI therapies, however, it is uncertain what the magnitude of the rebate is since the details are commercial in confidence. This lack of transparency is not necessarily negative as it enables companies to offer substantial discounts without being concerned about commercial risks due to reference pricing. 97 However, this also creates issues as there is a lack of visibility of the comparator price resulting in a possible underestimation of the cost‐effectiveness because of high prices being used in cost‐effectiveness analysis. 56

Often a performance based financial risk share agreement is also needed in conjunction with these special pricing arrangements. As mentioned previously, payers can manage the treatment duration using stopping rules. 81 Another example of financial management is through expenditure caps. This can either be based on agreed utilisation rates and a 50% rebate for expenditure beyond the agreed cap (as was the case for pembrolizumab) 38 or even with a 100% rebate (nivolumab). 57

Finally, the issue of ICI combination therapies needs to be mentioned. The financial implication of having to pay for 2 ICI therapies is potentially devastating. However, a classic HTA tool, namely cost minimisation analysis, has proven useful for indirectly managing the risk. Decision makers use cost minimisation analysis when it turns out that the clinical effectiveness is equivalent. 98 Briggs et al. 99 deemed this approach dead back in 2001, but it is still actively being used when a superiority claim of ICI combination therapies over monotherapy is not possible because of immature data. 72 , 82

4. CONCLUSION

This review of the reimbursement decisions and subsequent financial impact in Australia and the UK suggests that the costs of ICI therapies have been well managed so far. The cancer drug fund in England and Wales stayed within budget and in Australia ICI drugs only account for 5% of the total spend in 2019. Through risk agreements and managed entry programmes, the example of ICI therapies illustrates that industry and payers can effectively collaborate to ensure that innovative, but expensive, drugs can be made readily available to patients.

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

All authors contributed to the conception, drafting and approval of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

No funding was received for this piece of research.

Kim H, Liew D, Goodall S. Cost‐effectiveness and financial risks associated with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:1703–1710. 10.1111/bcp.14337

REFERENCES

- 1. da Veiga CRP, da Veiga CP, Drummond‐Lage AP. Concern over cost of and access to cancer treatments: a meta‐narrative review of nivolumab and pembrolizumab studies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;129:133‐145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Specenier P. Ipilimumab in melanoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(8):811‐826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Ipilimumab, concentrate solution for I.V. infusion, 50 mg in 10 mL, 200 mg in 40 mL, Yervoy®,July 2011. 2011; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2011-07/pbac-psd-ipilimumab-july11

- 4. Dickson RB, Bagust A, et al. Ipilimumab for previously treated unresectable malignant melanoma: a single technology appraisal. 2011; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta268/documents/melanoma-stage-iii-or-iv-ipilimumab-evidence-review-group-report3

- 5. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Ipilimumab, concentrate solution for I. V infusion, 50 mg in 10 mL, 200 mg in 40 mL, Yervoy® ‐ November 2012. 2012; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2012-11/ipilimumab

- 6. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Ipilimumab for previously treated advanced (unresectable or metastatic) melanoma (TA268). 2012; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta268

- 7. Dranitsaris G, Zhu X, Adunlin G, Vincent MD. Cost effectiveness vs. affordability in the age of immuno‐oncology cancer drugs. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(4):351‐357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sola‐Morales O, Volmer T, Mantovani L. Perspectives to mitigate payer uncertainty in health technology assessment of novel oncology drugs. J Mark Access Health Policy. 2019;7(1):1562861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. INAHTA, T.i.n.o.a.f.h.t.a . HTA glossary. 2019; Available from: http://htaglossary.net/HomePage

- 10. Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision modelling for health economic evaluation. 2006: OUP Oxford.

- 11. Hjelmgren J, Berggren F, Andersson F. Health economic guidelines‐‐similarities, differences and some implications. Value Health. 2001;4(3):225‐250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Avelumab for treating metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma (TA517). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta517

- 13. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab in combination with ipilimumab for treating advanced melanoma (TA400). 2016; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta400

- 14. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Ipilimumab for previously untreated advanced (unresectable or metastatic) melanoma (TA319). 2014; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta319 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . The Deed of Agreement Process. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/industry/listing/elements/deeds-agreement/c-deed-of-agreement

- 16. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for treating locally advanced unresectable or metastatic urothelial cancer after platinum‐containing chemotherapy (TA530). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta530

- 17. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for treating locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum‐containing chemotherapy (TA519). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta519

- 18. (PBS), A.P.B.S . The Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/home

- 19. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Ipilimumab, concentrate solution for I.V. infusion, 50 mg in 10 mL, 200 mg in 40 mL, Yervoy® ‐ March 2012. 2012; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2012-03/ipilimumab

- 20. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for untreated PD‐L1‐positive metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer (TA531). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta531

- 21. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for advanced melanoma not previously treated with ipilimumab (TA366). 2015; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta366

- 22. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for treating advanced melanoma after disease progression with ipilimumab (TA357). 2015; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta357

- 23. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (melanoma); 50 mg injection: powder for, 1 vial, 100 mg injection: powder for, 1 vial; Keytruda® – March 2015. 2015; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2015-03/pembrolizumab-keytruda-psd-03-2015

- 24. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for adjuvant treatment of resected melanoma with high risk of recurrence (TA553). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta553

- 25. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for untreated PD‐L1‐positive locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer when cisplatin is unsuitable (TA522). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta522

- 26. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (adj melanoma): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac‐meetings/psd/2018‐11/Pembrolizumab‐‐psd‐november‐2018

- 27. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (Melanoma): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-07/files/pembrolizumab-melanoma-psd-july-2019.pdf

- 28. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (mCRC): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; keytruda®. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-03/pembrolizumab-solution-psd-march-2019

- 29. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (PMBCL): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-11/Pembrolizumab-PMBCL

- 30. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for treating relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (TA540). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta540

- 31. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (rrcHL), powder for I.V. infusion, 50 mg and 100 mg vials, Keytruda®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-08/pembrolizumab-rrchl-powder-for-i.v.-infusion-50-mg-and-1-psd-august-2017

- 32. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (SCCHN): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 ml; Keytruda®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-07/Pembrolizumab-SCCHN-psd-july-2018

- 33. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (urothelial cancer): Powder for injection 50 mg, Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-11/pembrolizumab-urothelial-cancer-psd-november-2017

- 34. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (urothelial cancer): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-07/Pembrolizumab-psd-july-2018

- 35. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for treating PD‐L1‐positive non‐small‐cell lung cancer after chemotherapy (TA428). 2017; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta428

- 36. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab for untreated PD‐L1‐positive metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer (TA447). 2017; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta447

- 37. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab with pemetrexed and platinum chemotherapy for untreated, metastatic, non‐squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer (TA557). 2019; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta557

- 38. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (NSCLC): Powder for injection 50 mg; Keytruda®. 2016; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2016-11/pembrolizumab-nsclc-keytruda-psd-november-2016

- 39. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (NSCLC): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL, Powder for injection 50 mg; Keytruda®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-03/pembrolizumab-psd-march-2017

- 40. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (NSCLC): Powder for injection 50 mg, Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-11/pembrolizumab-psd-november-2017

- 41. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (NSCLC): Powder for injection 50 mg, solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-03/Pembrolizumab-nsclc-psd-march-2018

- 42. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (NSCLC): Powder for injection 50 mg; Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-07/Pembrolizumab-Keytruda-psd-july-2018

- 43. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Pembrolizumab with carboplatin and paclitaxel for untreated metastatic squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer (TA600). 2019; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta600

- 44. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab +chemo (NSCLC): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-11/Pembrolizumab-NSCLC-psd-november-2018

- 45. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Pembrolizumab (NSCLC): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL; Keytruda. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-07/files/pembrolizumab-nsclc-psd-july-2019.pdf

- 46. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for treating advanced (unresectable or metastatic) melanoma (TA384). 2016; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta384

- 47. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (melanoma), concentrate solution for infusion, 10 mg/mL, 1 x 4 mL vial, concentrate solution for infusion, 10 mg/mL, 1 x 10 mL vial, Opdivo®. 2015; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2015-07/nivolumab-opdivo-psd-july-2015

- 48. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (melanoma), concentrate solution for infusion, 10 mg/mL, 1 x 4 mL vial, 1 x 10 mL vial, Opdivo®. 2015; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2015-11/nivolumab-opdivo-psd-11-2015

- 49. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for previously treated squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer (TA483). 2017; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta483

- 50. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for previously treated non‐squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer (TA484). 2017; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta484

- 51. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (NSCLC): 40mg in 4ml (10mg/mL concentrate for IV infusion) 100mg in 10mL (10mg/mL concentrate for IV infusion), Opdivo®. 2016; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2016-03/nivolumab-opdivo-sq-psd-03-2016

- 52. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (squamous NSCLC): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. 2016; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2016-11/nivolumab-squamous-nsclc-psd-november-2016

- 53. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (NSCLC): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-03/nivolumab-psd-nsclc-march-2017

- 54. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for previously treated advanced renal cell carcinoma (TA417). 2016; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta417

- 55. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (RCC): 40 mg in 4 mL (10mg/mL concentrate for IV infusion) 1 × 4 mL vial 100 mg/10 mL injection (10mg/mL concentrate for IV infusion) 1 × 10 mL vial, Opdivo®. 2016; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2016-07/nivolumab-psd-july-2016

- 56. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (RCC): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. 2016; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2016-11/nivolumab-rcc-psd-november-2016

- 57. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-03/nivolumab-rcc-psd-march-2017

- 58. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for treating squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck after platinum‐based chemotherapy (TA490). 2017; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta490

- 59. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (SCCHN): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-11/nivolumab-psd-november-2017

- 60. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (SCCHN): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-03/Nivolumab-psd-march-2018

- 61. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for adjuvant treatment of completely resected melanoma with lymph node involvement or metastatic disease (TA558). 2019; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta558

- 62. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (Adj melanoma): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL; Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 ml; Opdivo®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-07/Nivolumab-malignant-melanoma-psd-july-2018

- 63. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (Adj Melanoma): Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-03/nivolumab-melanoma-psd-march-2019

- 64. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Recommendations made by the PBAC ‐ November 2019. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/pbac-outcomes/recommendations-made-by-the-pbac-november-2019

- 65. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab for treating relapsed or refractory classical Hodgkin lymphoma (TA462). 2017; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta462

- 66. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Durvalumab for treating locally advanced unresectable non‐small‐cell lung cancer after platinum‐based chemoradiation (TA578). 2019; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta578

- 67. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Durvalumab: Solution for I.V. infusion 120 mg in 2.4 mL, Solution for I.V. infusion 500 mg in 10 mL; Imfinzi®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-11/Durvalumab-psd-november-2018

- 68. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Durvalumab (NSCLC): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 120 mg in 2.4 mL, Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 500 mg in 10 mL; Imfinzi. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-07/files/durvalumab-nsclc-psd-july-2019.pdf

- 69. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Durvalumab (urothelial cancer): Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 120 mg in 2.4 mL, Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 500 mg in 10 mL; Imfinzi. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-07/files/durvalumab-uc-psd-july-2019.pdf

- 70. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab (melanoma), concentrate solution for infusion: 10 mg/mL, 1 x 4 mL vial, 10 mg/mL, 1 x 10 mL vial, Opdivo®, plus Ipilimumab, concentrate solution for infusion: 5 mg/mL, 1 x 40 mL vial, 5 mg/mL, 1 x 10 mL vial, Yervoy®, Bristol Myers Squibb. 2015; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2015-11/nivolumab-opdivo-plus-ipilimumab-yervoy-psd-11-2015

- 71. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab and Ipilimumab (melanoma): Nivolumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Opdivo®. Ipilimumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 50 mg in 10 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 200 mg in 40 mL; Yervoy®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-03/nivolumab-and-ipilimumab-psd-march-2017

- 72. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab and ipilimumab (malignant melanoma): Nivolumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL; Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Ipilimumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 50 mg in 10 mL; Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 200 mg in 40 mL; Opdivo® and Yervoy®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-07/Nivolumab-psd-july-2018

- 73. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Nivolumab with ipilimumab for untreated advanced renal cell carcinoma (TA581). 2019; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta581 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab and ipilimumab (renal cell carcinoma): Nivolumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL; Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 10 mL; Ipilimumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 50 mg in 10 mL; Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 200 mg in 40 mL; Opdivo® and Yervoy®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-07/Nivolumab-ipilimumab-psd-july-2018

- 75. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Nivolumab And Ipilimumab (1L RCC): nivolumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion 40 mg in 4 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion, 100 mg in 10 mL; ipilimumab: Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion, 50 mg in 10 mL, Injection concentrate for I.V. infusion, 200 mg in 40 mL; Opdivo® and Yervoy®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-11/Nivolumab-And-Ipilimumabpsd-november-2018

- 76. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Atezolizumab for treating locally advanced or metastatic non‐small‐cell lung cancer after chemotherapy (TA520). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta520

- 77. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Atezolizumab: Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 1200 mg in 20 mL; Tecentriq®. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2017-11/atezolizumab-psd-november-2017

- 78. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Atezolizumab for untreated PD‐L1‐positive locally advanced or metastatic urothelial cancer when cisplatin is unsuitable (TA492). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta492

- 79. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Atezolizumab for treating locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma after platinum‐containing chemotherapy (TA525). 2018; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta525

- 80. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Atezolizumab: Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 1200 mg in 20 mL; Tecentriq (July 2019). 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-07/files/atezolizumab-psd-july-2019.pdf

- 81. (NICE), N.I.f.H.a.C.E . Atezolizumab in combination for treating metastatic non‐squamous non‐small‐cell lung cancer (TA584). 2019; Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta584

- 82. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Atezolizumab and Bevacizumab: atezolizumab: Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 1200 mg in 20 mL; bevacizumab: Solution for I.V. infusion 100 mg in 4 mL, Solution for I.V. infusion 400 mg in 16 mL; Tecentriq® and Avastin®. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2019-03/atezolizumab-and-bevacizumab-psd-march-2019

- 83. (PBAC), A.P.B.A.C . Avelumab: Solution concentrate for I.V. infusion 200 mg in 10 mL; Bavencio®. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/pbs/industry/listing/elements/pbac-meetings/psd/2018-07/Avelumab-psd-july-2018

- 84. EMA, E.M.A . Ipilimumab summary of product characteristics. 2011; Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/yervoy-epar-product-information_en.pdf

- 85. Kim H, Comey S, Hausler K, Cook G. A real world example of coverage with evidence development in Australia ‐ ipilimumab for the treatment of metastatic melanoma. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2018;11(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Kim H, Goodall S, Liew D. Health technology assessment challenges in oncology: 20 years of value in health. Value Health. 2019;22(5):593‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . Efficient Funding of Chemotherapy (EFC) – Section 100 Arrangements. 2019; Available from: https://www.pbs.gov.au/info/browse/section-100/chemotherapy

- 88. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . About the PBS. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/about-the-pbs

- 89. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . Expenditure and prescriptions twelve months to 30 June 2014. 2014; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/statistics/2013-2014-files/expenditure-and-prescriptions-12-months-to-30-june-2014.pdf

- 90. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . Expenditure and prescriptions twelve months to 30 June 2015. 2015; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/statistics/2014-2015-files/exp-prs-book-01-2014-15.pdf

- 91. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . Expenditure and Prescriptions Twelve Months to 30 June 2016. 2016; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/statistics/expenditure-prescriptions/2015-2016/expenditure-prescriptions-report-2015-16.pdf

- 92. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . Expenditure and Prescriptions Twelve Months to 30 June 2017. 2017; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/news/2017/12/pbs-expenditure-prescriptions-2016-17

- 93. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . Expenditure and Prescriptions Twelve Months to 30 June 2018. 2018; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/statistics/expenditure-prescriptions/expenditure-prescriptions-twelve-months-to-30-june-2018

- 94. (DoH), A.G.D.o.H . PBS Expenditure and Prescriptions Report 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019. 2019; Available from: http://www.pbs.gov.au/statistics/expenditure-prescriptions/2018-2019/PBS_Expenditure_and_Prescriptions_Report_1-July-2018_to_30-June-2019.pdf

- 95. Team, N.E.C.D.F . Appraisal and Funding of Cancer Drugs from July 2016 (including the new Cancer Drugs Fund). 2016.

- 96. Hawkes N. New cancer drugs fund keeps within £340m a year budget. BMJ. 2018;360:k461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Holtorf A‐P, Gialama F, Wijaya KE, Kaló Z. External reference pricing for pharmaceuticals—a survey and literature review to describe best practices for countries with expanding healthcare coverage. Value Health Regional Issues. 2019;19:122‐131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Stoddart GL, Torrance GW. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 99. Briggs AH, O'Brien BJ. The death of cost‐minimization analysis? Health Econ. 2001;10(2):179‐184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]