Abstract

Following the 2013 public subsidy of pregabalin in Australia for neuropathic pain not responding to other medicines, use and misuse increased substantially. We used pharmaceutical dispensing claims for a 10% sample of Australians to quantify initiation, discontinuation and dispensing of other analgesics before and after initiation. We identified 130 770 people initiating pregabalin between 2013/14 and 2017/18 (median age: 61 years; 56.8% female). Discontinuation rates at 1‐year increased from 77.0% in 2013/14 to 85.9% in 2017/18; 38% only had 1 dispensing. Approximately 1/3 (37.5%) initiated on the lowest strength capsule (25 mg) with only 31.2% later up‐titrating to a higher strength. 47.4% and 53.0% were dispensed opioids within 180 days before and after pregabalin initiation, respectively. Many individuals are using pregabalin for short treatment durations and low dose ranges not consistent with treatment of neuropathic pain, which is generally a chronic condition. This may suggest poorer tolerability than observed in clinical trials, or use for other conditions, some of which may be for indications where the balance of benefits and risk is less clear.

Keywords: Australia, discontinuation, gabapentinoids, initiation, pharmacoepidemiology, pregabalin

What is already known about this subject

Pregabalin use has been increasing both in Australia and worldwide, with a corresponding increase in harms.

There are concerns that pregabalin is being prescribed for non‐neuropathic pain syndromes, such as low back pain, despite evidence of ineffectiveness for these conditions.

What this study adds

We found high rates of initiation on low‐strength capsules, with limited up‐titration to therapeutic doses.

Discontinuation rates were high, suggesting poor tolerability or use for indications other than neuropathic pain with poor risk–benefit profiles, prompting cessation of therapy.

Opioid dispensing was common, both before and after initiation with pregabalin, despite their limited efficacy to treat neuropathic pain and increased risks of harm in this context.

1. INTRODUCTION

Pregabalin is a gabapentinoid with analgesic, anxiolytic and anticonvulsant properties. In clinical trials, pregabalin was superior to placebo for the treatment of neuropathic pain and provided similar pain relief as other medicines such as amitriptyline and gabapentin. 1 Pregabalin use is on the rise globally, 2 , 3 , 4 with growing concerns about off‐label use and misuse. 5 , 6 Many people initiating pregabalin do not have a diagnosis for an approved indication and there is suspicion that pregabalin is being prescribed for non‐neuropathic pain, particularly low back pain, despite evidence that it is ineffective for this condition. 2 , 3 , 7

Pregabalin is accompanied by a high risk of adverse events such as dizziness, somnolence, peripheral oedema and dry mouth, 1 , 8 , 9 and has recently been associated with an increased risk of suicidal behaviour and unintentional overdose. 10 Pregabalin has abuse potential, particularly in people with substance use disorders, and when combined with opioids increases the risk of overdose‐related mortality. 6 , 11 In Australia, increases in pregabalin‐related overdose and ambulance attendances have increased dramatically in recent years. 5 , 12 In the UK, pregabalin was reclassified as a controlled substance in 2019 due to concerns over increasing gabapentinoid‐related mortality. 13

The Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), the national government programme that provides subsidised access to medicines, listed pregabalin for subsidy in March 2013 for the treatment of neuropathic pain not controlled by other medicines only. Since then, dispensing of pregabalin increased 2.7‐fold over the first 3 years of listing with a concomitant rise in poisonings and deaths. 5 The reason for this dramatic increase in prescribing is unclear. Thus, to help understand who is being prescribed pregabalin and how it is being used, in this study we describe the characteristics of people initiating pregabalin since it was subsidised in Australia, their individual patterns of use in the first year after treatment initiation, and dispensing of other medicines before and after initiation.

2. METHODS

2.1. Context and data source

All Australian residents are eligible for subsidised access to prescribed medicines through the PBS. We used PBS dispensing claims for a 10% random sample of all PBS‐eligible people between 1 March 2013 and 30 June 2018. This is a standard dataset provided by the Australian Government Department of Human Services for analytical use and is selected based on the last digit of each individual's randomly assigned unique identifier. To protect privacy, all dates are offset by +14 or −14 days; this offset is the same for each individual. Private dispensings (i.e. medicines not dispensed through the PBS and for which the consumer pays the entire cost out‐of‐pocket) are not captured in these data. However, since its subsidy, approximately only 6% of pregabalin prescriptions have been private. 14

2.2. Study population

We identified all people ≥18 years with a first dispensing of PBS‐subsidised pregabalin between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2018. As some people may have switched from privately prescribed pregabalin to subsidised pregabalin immediately after its listing, we excluded individuals with their first recorded dispensing between 1 March 2013 and 30 June 2013 as a washout period. For our description of patterns of initiation, we included the full cohort of people who initiated between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2018. For analyses of pregabalin use in the first year after initiation (specifically, the total number of dispensings and discontinuations, and patterns of use of other medicines), we restricted the cohort to people with at least 1 full year of follow‐up who initiated between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2017 as complete data were only available until 30 June 2018 at the time of this study.

2.3. Medicines of interest

Pregabalin is approved in Australia for treatment of neuropathic pain and seizures. On 1 March 2013 pregabalin was PBS‐listed for the treatment of refractory neuropathic pain not controlled by other medicines only. It is available in capsule strengths of 25, 75, 150 and 300 mg and the standard pack size is 56 capsules. Apart from pregabalin, we extracted information on other medicines used to treat pain and/or mental health conditions dispensed in the 180 days preinitiation and 180 postinitiation using World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes. The date of initiation was included in the postinitiation period. These included: tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs; N06AA), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs; N06AX16, N06AX21, N06AX23), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs; N06AB), other antidepressants (N06A, excluding TCAs, SNRIs and SSRIs), other antiepileptics (N03A, excluding pregabalin), opioids (N02A), prescription nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; M01), antipsychotics (N05A), and benzodiazepines (N05B, N05C). Gabapentin, which like pregabalin is a gabapentinoid, is only subsidised through the PBS for the treatment of seizures and not neuropathic pain. While gabapentin is subsidised through Repatriation PBS for eligible veterans and their families for the treatment of refractory neuropathic pain and seizures, we did not have data for medicines subsidised through the Repatriation PBS.

2.4. Patterns of use

We calculated counts as well as incidence rates per 1000 population using the Australian Bureau of Statistics population estimates, 15 with estimates scaled up to account for the data being a representative 10% sample of Australian residents. We identified the following measures for pregabalin in the 365 days after initiation: total number of dispensings; total number of defined daily doses dispensed; and maximum capsule strength dispensed. The defined daily dose for pregabalin is 300 mg. We measured discontinuation as a gap in dispensing of 90 days or greater and counted the first discontinuation only. In our study population, the 95th percentile for time between dispensings was 90 days, thus allowing a generous grace period for individuals to miss doses or for late refills and is a conservative estimate of discontinuation. We also identified the proportion of people that up‐titrated to a higher capsule strength among people initiating on the lowest strength (25 mg). While older, frail individuals and those with renal impairment (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 mL/min) may require smaller initial doses and/or slower titration, these are likely to represent a minority of people initiating pregabalin and for most individuals ongoing use of the 25‐mg capsule alone is likely to represent a subtherapeutic dose. 16

2.5. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Incidence

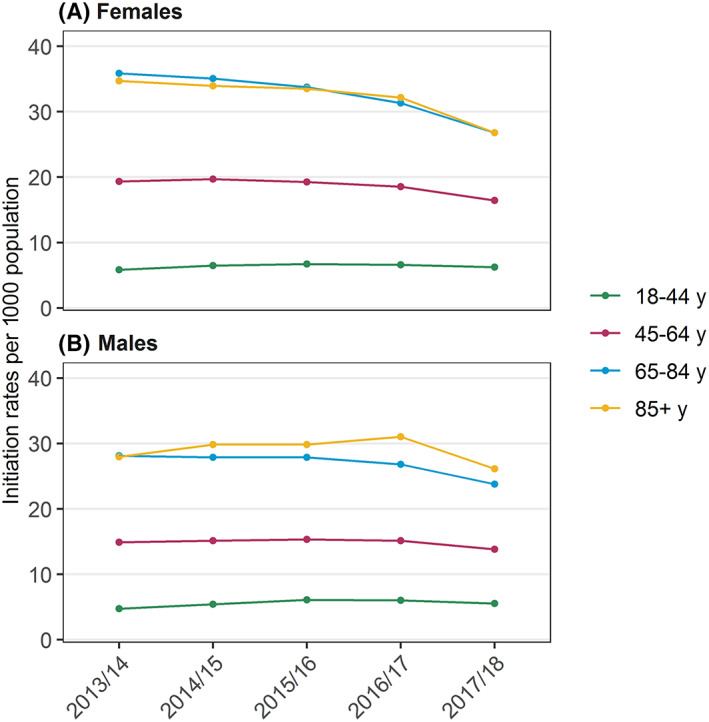

In our 10% sample of PBS‐eligible Australians, we identified 130 770 people initiating pregabalin between 1 July 2013 and 30 June 2018. Overall, the median age at initiation was 61 years (interquartile range, 47–72), and 56.8% were female. The age and sex distributions were relatively consistent across years (Table 1). Initiation rates were 14.2/1000 population in 2013/14, decreasing slightly to 12.9/1000 in 2017/18. Initiation rates were highest in people aged 65–84 years and ≥85 years, and slightly higher in women (Figure 1). The majority of new users (92.7%) initiated on capsule strengths of 75 mg or less, and a substantial proportion initiated on the 25‐mg strength only, which increased from 29.5% in 2013/14 to 46.4% in 2017/18.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of people initiating pregabalin in sample since its subsidy and patterns of use in first year (July 2013–June 2018)

| 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Number of people initiating pregabalin | 25 491 (100.0) | 26 635 (100.0) | 27 274 (100.0) | 26 883 (100.0) | 24 487 (100.0) |

| Age group (y) | |||||

| 18–44 | 4689 (18.4) | 5333 (20.0) | 5800 (21.3) | 5765 (21.4) | 5473 (22.4) |

| 45–64 | 9797 (38.4) | 10 092 (37.9) | 10 140 (37.2) | 10 023 (37.3) | 9130 (37.3) |

| 65–84 | 9590 (37.6) | 9735 (36.5) | 9825 (36.0) | 9563 (35.6) | 8575 (35.0) |

| ≥85 | 1415 (5.6) | 1475 (5.5) | 1509 (5.5) | 1532 (5.7) | 1309 (5.3) |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 10 670 (41.9) | 11 262 (42.3) | 11 839 (43.4) | 11 846 (44.1) | 10 918 (44.6) |

| Female | 14 821 (58.1) | 15 373 (57.7) | 15 435 (56.6) | 15 037 (55.9) | 13 569 (55.4) |

| Capsule strength at initiation | |||||

| 25 mg | 7520 (29.5) | 9587 (36.0) | 11 025 (40.4) | 11 703 (43.5) | 11 374 (46.4) |

| 75 mg | 15 436 (60.6) | 15 073 (56.6) | 14 381 (52.7) | 13 420 (49.9) | 11 755 (48.0) |

| 150 mg | 1910 (7.5) | 1420 (5.3) | 1275 (4.7) | 1155 (4.3) | 877 (3.6) |

| 300 mg | 274 (1.1) | 196 (0.7) | 205 (0.8) | 195 (0.7) | 175 (0.7) |

| Multiple | 351 (1.4) | 359 (1.3) | 388 (1.4) | 407 (1.5) | 306 (1.2) |

| No. dispensings in first year a | |||||

| 1 | 8157 (32.0) | 9720 (36.5) | 10 708 (39.3) | 11 360 (42.3) | |

| 2–4 | 6101 (23.9) | 6794 (25.5) | 7124 (26.1) | 7046 (26.2) | |

| 5–12 | 7136 (28.0) | 6648 (25.0) | 6366 (23.3) | 5741 (21.4) | |

| >12 | 4097 (16.1) | 3473 (13.0) | 3076 (11.3) | 2736 (10.2) | |

| Total defined daily dose dispensed in the first year a , b | |||||

| 0–14 | 8600 (33.7) | 10 527 (39.5) | 11 730 (43.0) | 12 522 (46.6) | |

| 15–28 | 3142 (12.3) | 3568 (13.4) | 3701 (13.6) | 3786 (14.1) | |

| 29–90 | 5433 (21.3) | 5559 (20.9) | 5679 (20.8) | 5292 (19.7) | |

| 91–365 | 6989 (27.4) | 6035 (22.7) | 5313 (19.5) | 4564 (17.0) | |

| >365 | 1327 (5.2) | 946 (3.6) | 851 (3.1) | 719 (2.7) | |

| Discontinuation in first year a | 19 619 (77.0) | 21 709 (81.5) | 22 859 (83.8) | 23 105 (85.9) | |

Patterns of use in first year postinitiation presented for people who initiated prior to 1 July 2017 only.

The defined daily dose for pregabalin is 300 mg.

FIGURE 1.

Initiation rates per 1000 population over time by age and sex, July 2013 to June 2018

3.2. Patterns of use in first year after initiation

Among people initiating prior to 1 July 2017 (n = 106 283), pregabalin discontinuation rates at 1 year were high; discontinuation increased from 77.0% (n = 19 619) of people initiating in 2013/14 to 85.9% (n = 23 105) in 2016/17 (Table 1), and the proportion of people with only 1 dispensing increased from 32.0% (n = 8157) in 2013/14 to 42.0% (n = 11 360) in 2016/17. Overall, the median time to discontinuation was 103 days (interquartile range 90–219). Among people with >1 dispensing (n = 68 553), the median time to discontinuation was 209 days. People who initiated on 300 mg were least likely to discontinue (74.0%), followed by those who initiated on the 150 mg (80.4%), 25 mg (85.2%) and 75 mg (85.6%). Among pregabalin users who initiated on strengths of 25 mg (n = 39 835; 37.5%), 37.2% discontinued after their first dispensing, while 31.5% stayed on the same capsule strength. Only 31.2% (n = 12 444) were dispensed a higher capsule strength indicating up‐titration in the first year.

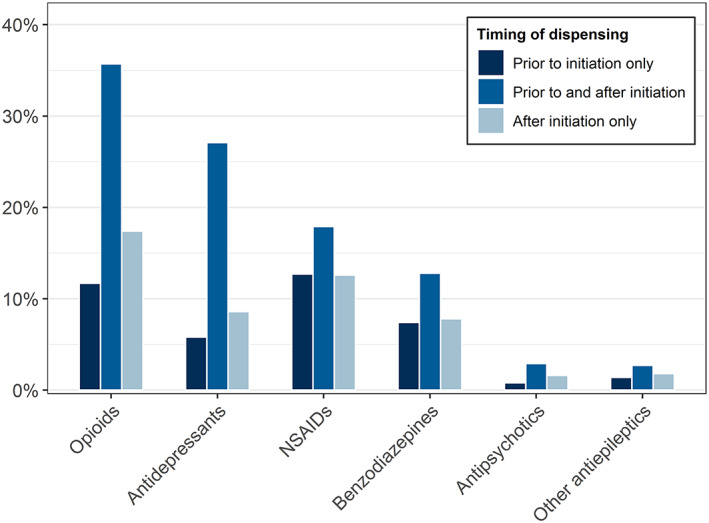

Many people were dispensed opioids (n = 50 346; 47.4%), antidepressants (n = 34 961; 32.9%), NSAIDs (n = 32 582; 30.6%) and benzodiazepines (n = 21 474; 20.2%) in the 6 months prior to pregabalin initiation; the majority also continued to use these medicines in the 6 months following pregabalin initiation (Figure 2). In pregabalin initiators with a prior opioid dispensing, 75.3% (n = 37 903) continued to be dispensed opioids after initiating pregabalin; in initiators with a prior antidepressant dispensing, 82.4% (n = 28 797) continued antidepressant use after initiating pregabalin; in those with a prior NSAID dispensing, 58.5% (n = 19 072) continued use after initiating pregabalin. Only 11.8% (n = 12 539), 8.3% (n = 8775) and 13.2% (n = 14 051) of the cohort were dispensed a TCA, SNRI or SSRI respectively. Prior dispensing of other antiepileptics, including gabapentin, was uncommon.

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of dispensing of other medicines within 180 days before and 180 days after initiation of pregabalin (June 2013 to July 2017). NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs

4. DISCUSSION

Following the PBS subsidy of pregabalin, we observed high rates of pregabalin initiation from 2013/14 to 2016/17 with only a slight drop in 2017/18. However, consistent with other studies, 7 , 17 , 18 we observed high rates of discontinuation which have been increasing over time, suggesting suboptimal efficacy or low tolerability of pregabalin for the conditions for which it is being used. The lower discontinuation rates in people that initiated on the higher capsule strengths may indicate a better risk–benefit profile, use for different indications, or use in different populations. For neuropathic pain, pregabalin is generally effective in clinical trials at doses of at least 150 or 300 mg daily, 1 , 16 and exhibits a dose–response relationship with increasing efficacy at higher doses. In our study, 38% of people were given an initial strength of 25 mg, and most of these people (69%) either discontinued after 1 dispensing or remained on this low strength without up‐titration. Real‐world prescribing of pregabalin may be to frailer patient population with higher rates of renal impairment compared with those in clinical trials, and lower doses are recommended in these individuals. 19 , 20 Australian medicine guidelines suggest starting patients on doses of 75 mg 21 ; however, the lack of up‐titration of the 25 mg to a therapeutic dose may result from limited clinical review, poor tolerance or adverse effects at higher doses, or treatment for off‐label indications.

Dispensing of other pain medicines, particularly opioids and prescription NSAIDs, was common despite limited evidence of their efficacy for neuropathic pain. 22 , 23 However, the low rates of prior antidepressant use (specifically TCAs, SSRIs and SNRIs) suggest that the majority of new pregabalin use is not consistent with the PBS restriction for neuropathic pain refractory to other first‐line medicines. Inconsistencies in the recommended uses of pregabalin in the treatment of neuropathic pain in evidence‐based guidelines could be contributing to clinician uncertainty about when to prescribe pregabalin. In contrast to the PBS restriction, Australian guidelines recommend analgesic adjuvants such as pregabalin for neuropathic pain, without restriction to second‐line. 24 Additionally, while pregabalin is registered for use in fibromyalgia and generalised anxiety disorder in the USA and Europe, respectively, neither of these are approved indications in Australia. The variations in recommendations and approvals by health regulatory bodies worldwide, compounded by drug company marketing for off‐label conditions 25 are no doubt contributing to the uncertainty around the optimal use of pregabalin; revision of PBS restrictions to be more in line with contemporary practice may be warranted.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is that we were able to measure population‐level incidence of use with certainty due to the representative nature of our sample. However, an important limitation is the lack of clinical information, such as the indication for which pregabalin and other medicines were prescribed. As such we could not identify off‐label use or the appropriateness of prescribing with any certainty. Secondly, we did not have information on the prescribed daily dose; some people may have been taking multiple 25‐mg capsules a day to reach a higher dose. Lastly, we have not captured over‐the‐counter analgesics in our study, such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. However, these are not guideline‐recommended treatments and there is little evidence for the efficacy of NSAIDs for neuropathic pain. 23

5. CONCLUSION

Our study found high rates of pregabalin initiation and discontinuation following a single dispensing, in addition to high rates of ongoing low dose use without evidence of up‐titration. There are several potential reasons for this. It may indicate that pregabalin is either being used for indications other than neuropathic pain with shorter treatment durations and lower dose ranges, or is less well tolerated in real‐world use compared to clinical trials. Additionally, it may partly be explained by differences in the trial populations compared with people prescribed pregabalin in actual clinical practice, such as higher rates of renal impairment. Regardless, in Australia, increased community availability has resulted in increasing rates of use, of which a significant proportion may be inappropriate. In some countries, concerns over gabapentinoids has led to regulatory responses such as the rescheduling of gabapentinoids in the UK; the Australian Therapeutics Goods Administration is now also considering approaches to reduce pregabalin‐related harms and misuse. 26

COMPETING INTERESTS

There are no competing interests to declare.

CONTRIBUTORS

AS conceived of and designed the study. SP acquired the data. TC and AS analysed the data. All authors contributed to interpretation of the results. TC and AS drafted the manuscript. AS, JB and SP revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Centre of Research Excellence in Medicines and Ageing (ID: 1060407) and a Cooperative Research Centre Project (CRC‐P) Grant from the Australian Government Department of Industry, Innovation and Science (ID: CRC‐P‐439). A.L.S. is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (#1158763). We thank the Australian Government Department of Human Services for providing the data.

Chiu T, Brett J, Pearson S‐A, Schaffer AL. Patterns of pregabalin initiation and discontinuation after its subsidy in Australia. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;86:1882–1887. 10.1111/bcp.14276

The study has ethics approval from the New South Wales Population and Health Services Ethics Committee (2013/11/494). The Australian Government Department of Human Services External Request Evaluation Committee approved access to the data (approval code: MI8695).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Australian Government Department of Human Services (https://www.humanservices.gov.au/organisations/about-us/statistical-information-and-data). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Derry S, Bell RF, Straube S, Wiffen PJ, Aldington D, Moore RA. Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;1:CD007076 10.1002/14651858.CD007076.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Montastruc F, Loo SY, Renoux C. Trends in first gabapentin and Pregabalin prescriptions in primary Care in the United Kingdom, 1993‐2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2149‐2151. 10.1001/jama.2018.12358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johansen ME. Gabapentinoid use in the United States 2002 through 2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):292‐294. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kwok H, Khuu W, Fernandes K, et al. Impact of unrestricted access to Pregabalin on the use of opioids and other CNS‐active medications: a cross‐sectional time series analysis. Pain Med. 2017;18(6):1019‐1026. 10.1093/pm/pnw351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cairns R, Schaffer AL, Ryan N, Pearson SA, Buckley NA. Rising pregabalin use and misuse in Australia: trends in utilization and intentional poisonings. Addiction. 2019;114(6):1026‐1034. 10.1111/add.14412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schifano F. Misuse and abuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: cause for concern? CNS Drugs. 2014;28(6):491‐496. 10.1007/s40263-014-0164-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Viniol A, Ploner T, Hickstein L, et al. Prescribing practice of pregabalin/gabapentin in pain therapy: an evaluation of German claim data. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e021535 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mathieson S, Maher CG, McLachlan AJ, et al. Trial of Pregabalin for acute and chronic sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(12):1111‐1120. 10.1056/NEJMoa1614292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Enke O, New HA, New CH, et al. Anticonvulsants in the treatment of low back pain and lumbar radicular pain: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. CMAJ. 2018;190(26):E786‐E793. 10.1503/cmaj.171333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Molero Y, Larsson H, D'Onofrio BM, Sharp DJ, Fazel S. Associations between gabapentinoids and suicidal behaviour, unintentional overdoses, injuries, road traffic incidents, and violent crime: population based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ. 2019;365:l2147 10.1136/bmj.l2147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gomes T, Greaves S, van den Brink W, et al. Pregabalin and the risk for opioid‐related death: a nested case–control study. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(10):732‐734. 10.7326/M18-1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crossin R, Scott D, Arunogiri S, Smith K, Dietze PM, Lubman DI. Pregabalin misuse‐related ambulance attendances in Victoria, 2012–2017: characteristics of patients and attendances. Med J Aust. 2019;210(2):75‐79. 10.5694/mja2.12036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mayor S. Pregabalin and gabapentin become controlled drugs to cut deaths from misuse. BMJ. 2018;363:k4364 10.1136/bmj.k4364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chidwick K. Pregabalin prescribing patterns in Australian general practice, 2012‐18. Presented at: GP19 Conference; October 25, 2019; Adelaide, Australia.

- 15. Australian Bureau of Statistics . 3101.0 ‐ Australian Demographic Statistics, Mar 2019. 2019. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3101.0 (accessed 3 Oct 2019).

- 16. Serpell M, Latymer M, Almas M, Ortiz M, Parsons B, Prieto R. Neuropathic pain responds better to increased doses of pregabalin: an in‐depth analysis of flexible‐dose clinical trials. J Pain Res. 2017;10:1769‐1776. 10.2147/JPR.S129832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wettermark B, Brandt L, Kieler H, Bodén R. Pregabalin is increasingly prescribed for neuropathic pain, generalised anxiety disorder and epilepsy but many patients discontinue treatment. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68(1):104‐110. 10.1111/ijcp.12182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Onakpoya IJ, Thomas ET, Lee JJ, Goldacre B, Heneghan CJ. Benefits and harms of pregabalin in the management of neuropathic pain: a rapid review and meta‐analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e023600 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Semel D, Murphy TK, Zlateva G, Cheung R, Emir B. Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of pregabalin in older patients with neuropathic pain: results from a pooled analysis of 11 clinical studies. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:85 10.1186/1471-2296-11-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raouf M, Atkinson TJ, Crumb MW, Fudin J. Rational dosing of gabapentin and pregabalin in chronic kidney disease. J Pain Res. 2017;10:275‐278. 10.2147/JPR.S130942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Australian Medicines Handbook . Pregabalin. 2019. https://amhonline.amh.net.au/chapters/neurological-drugs/antiepileptics/other-antiepileptics/pregabalin (accessed 3 Oct 2019).

- 22. McNicol ED, Midbari A, Eisenberg E. Opioids for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD006146 10.1002/14651858.CD006146.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moore RA, Chi C‐C, Wiffen PJ, et al. Oral nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10:CD010902 10.1002/14651858.CD010902.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Therapeutic Guidelines Limited . Neuropathic pain. eTG. 2019. https://tgldcdp.tg.org.au/viewTopic?topicfile=neuropathic‐pain&guideline (accessed 3 Oct 2019).

- 25. Tanne JH. Pfizer pays record fine for off‐label promotion of four drugs. BMJ. 2009;339:b3657 10.1136/bmj.b3657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Australian Government Therapeutic Goods Administration . Advisory Committee on Medicines meeting statement, Meeting 13, 1 February 2019. 2019. https://www.tga.gov.au/committee-meeting-info/acm-meeting-statement-meeting-13-1-february-2019 (accessed 3 Oct 2019).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Australian Government Department of Human Services (https://www.humanservices.gov.au/organisations/about-us/statistical-information-and-data). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study.