Abstract

Military veterans who could benefit from mental health services often do not access them. Research has revealed a range of barriers associated with initiating United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) care, including those specific to accessing mental health care (e.g., fear of stigmatization). More work is needed to streamline access to VA mental health-care services for veterans. In the current study, we interviewed 80 veterans from 9 clinics across the United States about initiation of VA mental health care to identify barriers to access. Results suggested that five predominant factors influenced veterans’ decisions to initiate care: (a) awareness of VA mental health services; (b) fear of negative consequences of seeking care; (c) personal beliefs about mental health treatment; (d) input from family and friends; and (e) motivation for treatment. Veterans also spoke about the pathways they used to access this care. The four most commonly reported pathways included (a) physical health-care appointments; (b) the service connection disability system; (c) non-VA care; and (d) being mandated to care. Taken together, these data lend themselves to a model that describes both modifiers of, and pathways to, VA mental health care. The model suggests that interventions aimed at the identified pathways, in concert with efforts designed to reduce barriers, may increase initiation of VA mental health-care services by veterans.

Keywords: mental health, access, veteran, qualitative

Over the last two decades, the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has identified improving access to health care as a priority area (e.g., Kehle, Greer, Rutks, & Wilt, 2011; Miller, 2001). This focus on access has intensified since the VA waitlist crisis in 2014 (Oppel & Shear, 2014). In response, the VA established the MyVA Access Initiative to strengthen veteran access to both VA and non-VA care (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2014a). Research consistent with this focus has identified a range of barriers to care including: lack of knowledge of VA eligibility and services (Wagner, Dichter, & Mattocks, 2015; Washington, Yano, Simon, & Sun, 2006), trouble navigating the health-care system (Gorman, Blow, Ames, & Reed, 2011; Johnson, Carlson, & Hearst, 2010), and logistical difficulties associated with traveling to appointments (Gorman et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2010; Washington, Bean-Mayberry, Riopelle, & Yano, 2011). Some of these barriers may be particularly relevant for specific veteran groups. For example, the need to travel long distances for care is particularly pertinent to the 36% of VA users located in rural areas (Goins, Williams, Carter, Spencer, & Solovieva, 2005; United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Rural Health, 2008).

Veterans in need of mental health care may face additional challenges in accessing care. For example, symptoms such as lack of motivation and trouble concentrating may further complicate veterans’ abilities to traverse an already challenging system. Indeed, research has found that more severe psychiatric symptoms are associated with increased access barriers (Drapalski, Milford, Goldberg, Brown, & Dixon, 2008). In addition, veterans may avoid seeking treatment based on negative beliefs about mental health care (Pietrzak, Johnson, Goldstein, Malley, & Southwick, 2009), or fear of negative consequences associated with seeking help (Gorman et al., 2011; Hoge et al., 2004; Stecker, Fortney, Hamilton, & Ajzen, 2007).

Veterans new to the VA system may have an especially difficult time accessing services. Specifically, they may lack knowledge of VA eligibility and services and have difficulty navigating the VA health-care system. These barriers also may limit access for veterans who have been ensconced in VA care for a long time (e.g., through primary care), but who are attempting to access a new type of service (e.g., mental health services).

Although the literature includes explorations of veterans’ perceptions of VA mental health-care access (including studies using data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Survey of Health Care Experience of Patients (SHEP), e.g., Burnett-Zeigler, Zivin, Ilgen, & Bohnert 2011; Budzi, Lurie, Singh, & Hooker 2010; Prentice, Davies, & Pizer 2014) and has detailed a number of facilitators and barriers that may influence the initiation of care (e.g., Elbogen et al., 2013; Ouimette et al., 2011; Spoont et al., 2014), the vast majority of these investigations have used quantitative approaches. These approaches are limited, however, in instances in which the structured-answer choices do not adequately capture the experiences of the participant (Duffy, 1987). In the case of facilitators and barriers to mental health care, a deeply personal topic for many veterans, providing an opportunity for veterans to expand upon how they made the decision to initiate (or not initiate) care provides a forum for gaining additional, richer, data. Further, confirmation of the themes already identified in the literature through this method would provide additional support for conclusions drawn from quantitative methods.

Relatedly, whereas the literature has focused on identifying factors that influence the initiation of care, there may be other aspects of access that have not been examined because of a primarily quantitative approach to the question. Indeed, a better understanding of the ways that veterans first get connected to VA mental health care is still needed. Accurately conceptualizing initiation of care is crucial to streamlining access and improving receipt of timely and appropriate services, including mental health services, for veterans.

In the current study, we used qualitative methods to develop a more complete understanding of veterans’ initial experiences accessing VA mental health care. These analyses were conducted as part of a larger, mixed-methods study that aimed to develop a veteran-centered measure of perceptions of access to health care: the Perceived Access Inventory (PAI; Pyne et al., 2018). Whereas the PAI represents a generalizable measure of perceived access, for the current article, we used qualitative methods to explore experiences by veterans initially accessing VA mental health care.

Method

Study Population

Eligible participants were United States military veterans between the ages of 18 and 70 years, with at least one positive screen for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), alcohol-use disorder (AUD), or major depressive disorder (MDD) documented in their VA medical record during the previous year. These screening measures are typically conducted in primary care settings. Veterans who screen positive for these disorders do not necessarily receive services for them, or are even aware that they screened positive for a mental health problem. Therefore, our sample included veterans with and without a history of using VA-based mental health services or being aware of what was in their medical record regarding these screens. However, we excluded veterans who screened positive but denied any distress related to the condition for which they screened positive, because they were unlikely to need mental health services. We also excluded veterans with documented psychosis or dementia in their VA medical records, as these conditions could potentially interfere with the informed-consent process and/or completion of the qualitative interview. We recruited participants from nine clinics: three separate clinics within each of three Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs; VISN 1 in the Northeast, VISN 16 in the Central South, and VISN 21 in the West).

Recruitment Procedures

We mailed recruitment packets to 585 eligible veterans across all three study VISNs. Recruitment packets included a letter briefly describing the study and stating that recipients would receive a call from the study team, unless they opted out by either calling study personnel or returning an enclosed, self-addressed, stamped response form. Veterans who did not opt out within 2 weeks (n = 496) were called by trained study staff to discuss study participation and confirm eligibility. Of these, 258 veterans were reached and 72 of these veterans (27.9% of those reached by phone; 12.3% of those sent a study packet) were included in the study. These 72 veterans, plus eight additional veterans recruited onsite, made up the final study sample (n = 80). Sampling was purposive, and intended to ensure adequate numbers of women and members of racial/ethnic minorities, as well as a mixture of veterans living in rural and urban areas, older and younger veterans, and veterans with and without a history of mental health-service access. All study procedures were approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (CIRB). Additional detail on this study’s opt-out design and recruitment procedures can be found in a previous peer-reviewed article from this study (Miller et al., 2017).

Study Sample

A total of 80 veterans participated in the study, approximately equally distributed across the three VISNs. Participants were mostly between 30 and 60 years old (M = 45.8 years; SD = 13.7 years), White (62.5%), non-Hispanic (71.3%), and male (75%), with approximately half living in rural areas (46.2%; see Table 1). As described in the previous article from this study (Miller et al., 2017), our recruitment strategy was generally successful in obtaining our desired sample, although study participants were more likely to have accessed VA-based mental health services in the past year than those who did not participate.

Table 1.

Study-Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | Sample (N = 80) |

|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 45.8 (13.7) |

| Gender: n (% female) | 20 (25.0) |

| Race: n (%) | |

| Native American | 2 (2.5) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 7 (8.8) |

| Black | 17 (21.3) |

| White | 50 (62.5) |

| Unknown | 11 (13.8) |

| Ethnicity: n (%) | |

| Hispanic | 8 (3.8) |

| Not Hispanic | 57 (71.3) |

| Unknown | 15 (18.8) |

| Mental health services used past year: n (%) | 53 (66.3) |

| Rural/urban: n (% rural) | 37 (46.2) |

Measures

In addition to a self-report demographic questionnaire, participating veterans completed a semistructured qualitative interview, designed in part based on the state-of-the-art (SOTA) access model (Fortney, Burgess, Bosworth, Booth, & Kaboli, 2011). The SOTA access model describes five dimensions of access to care, including Geographical (e.g., travel distance), Temporal (e.g., wait times for the next appointment), Financial (e.g., costs associated with getting care), Cultural (e.g., stigma associated with getting care), and Digital (e.g., connectivity to allow remote access to healthcare services). In addition to questions regarding these domains, the qualitative interview guide also included open-ended questions regarding the process of accessing VA medical and mental health services more generally (e.g., overall experience of receiving care at the VA).

Study Procedures

Interviews generally were conducted in person at the veteran’s local VA community-based outpatient clinic, with a small subset (n = 6) conducted over the telephone. Written informed consent was obtained for in-person participants, and CIRB-approved verbal consent was obtained for telephone participants. Study sessions involved administration of the aforementioned demographics questionnaire and semistructured qualitative interview, as well as additional measures unrelated to this article. Interviews were conducted by the qualitative team, which consisted of four researchers experienced in conducting qualitative interviews and analyses, including one communication scientist, one applied anthropologist, one nurse scientist, and one clinical psychologist. Study sessions took about 1.5–2 hr each, and veterans were provided with financial compensation for participating.

Analytic Plan

Qualitative interviews were audio recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim. The qualitative team (described in the previous section) undertook the coding and analysis of the resulting transcripts. Using a subset of transcribed interviews, the qualitative team used a modified form of directed content analysis to develop an original codebook to characterize interview content (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Directed content analysis was used to generate deductive codes from the SOTA Access Model. While reading transcripts, the team noticed other features of veterans’ experiences that could not be captured in the existing deductive codes; inductive codes were generated to capture this content. The resulting codebook therefore combined both deductive and inductive codes to describe interview content.

An iterative process was used to determine which deductive and inductive codes would comprise the final codebook. The qualitative team first read one transcript every 2 weeks to discuss deductive code application and inductive codes that may have been generated. All code definitions were discussed and refined orally, circulated via e-mail for written clarification, and incorporated into the next round of coding. After three months, no new inductive codes were proposed, and the codebook was finalized with 49 substantive codes grouped into six domains (Pyne et al., 2018).

In preparation for coding, one team member segmented all transcripts into a coding unit consisting of a question asked by the interviewer and the participant’s answer to that question. Once transcripts were segmented into units, qualitative team members coded interviews using ATLAS.ti qualitative management software (Muhr, 2017). To assess intercoder reliability, 20% of interviews were reviewed and discussed during periodic reliability meetings, with discrepancies in coding resolved by consensus.

The current article focuses on interview segments assigned a single code, entitled “Getting the Ball Rolling,” an inductive code describing factors influencing veterans access to VA mental health care for the first time. We used qualitative thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) for this article. Specifically, we first exported all coded segments of interview text to which the “Getting the Ball Rolling” code had been applied from the ATLAS.ti software into a separate text file. Next, Christopher J. Miller reviewed all segments in the text file and developed an analytic summary that described common themes within the data. This summary was first discussed among the full qualitative team and revised according to comments to take into consideration the relationship between the summary and results of other codes and analytic summaries. Then, it was presented before the full study team, who also offered comments in light of the overall research project concerning access to VA mental health care. Finally, Michelle J. Bovin reviewed the coded segments and resulting themes to create a model that accounted for the data and thematic findings.

Results

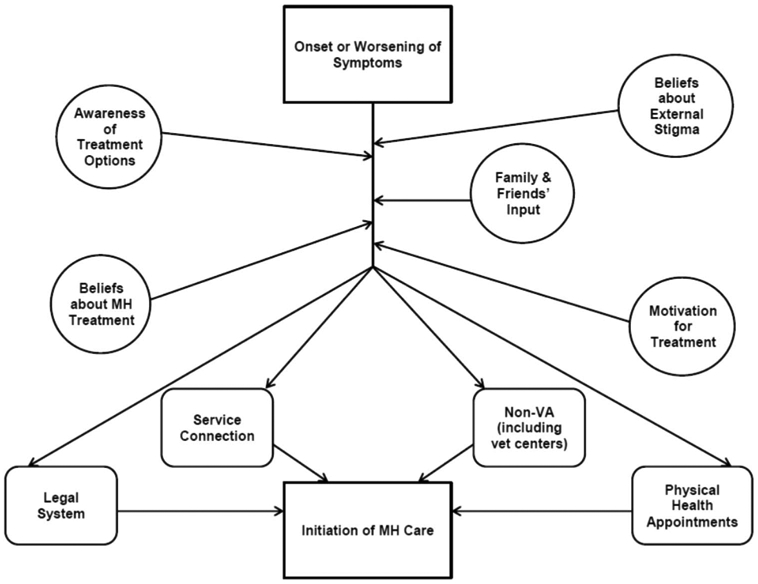

In total, the “Getting the Ball Rolling” code was applied to 299 interview segments. Examination of these segments suggested three superordinate themes: (a) onset or worsening of symptoms, which was the motivation for seeking treatment; (b) facilitators and barriers to getting help; and (c) the actual pathways that veterans followed that led them to initiate mental health services (see Figure 1). These themes and associated subthemes are discussed below.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the modifiers of and pathways to initial VA mental health-care access. The circles represent the modifiers of access to specialty mental health care, whereas the truncated squares represent commonly reported pathways to this care.

Onset/Worsening of Symptoms

The veterans in our sample noted that they did not think about accessing VA mental health services until they experienced, recognized, or saw a worsening of their mental health symptoms. Sometimes the onset/increase in symptoms was tied to a triggering event. One veteran noted the following.

I would say getting married was [the tipping point]. The stressors of experiencing something new when I was—I didn’t realize that I was depressed and angry and trying to learn to live with another person, even though we had been living together already it was more—it was a change of environment. (Participant 3028)

In other cases, veterans noticed that their symptoms were affecting their daily lives: “All I knew was I was very angry and I wanted to take somebody I work with and throw them in a trash can, which was my red flag, ‘Need help!’” (Participant 2009).

Although this symptom exacerbation was often not enough to prompt the veteran to contact VA mental health immediately, it served as the beginning of the pathway toward care for all the veterans who eventually did decide to seek services.

Barriers and Facilitators to Initiating Mental Health Treatment

Although onset or worsening of symptoms was the initial step in the pathway toward initiating care, not all veterans who experienced this onset or worsening eventually sought care. Veterans reported a number of barriers and facilitators which affected their decision to seek (or not to seek) help. In particular, five common subthemes, or factors, were identified during interviews: (a) Awareness of VA Mental Health Services; (b) Fear of Negative Consequences of Seeking Care; (c) Personal Beliefs About Mental Health Treatment; (d) Input From Family and Friends; and (e) Motivation for Treatment.

Awareness of VA mental health services or processes for obtaining them.

Many veterans reported not being provided with information about when, or how, to access VA mental health services. This frequently was discussed in the context of separating from the military. A number of veterans in our sample reported that they were not given any information about how to access VA services after separation, or if they were, these instructions were vague or unhelpful. Some veterans were also given incorrect information about access, such as being told they were not eligible for services based on noncombat status. Other veterans indicated that, although they were provided with some information about accessing services, they were overwhelmed by their other out-processing duties and were therefore unable to focus on this information at the time. Many participants commented that after separation, they got the impression that the focus of the military was to get them out as quickly as possible, rather than to ensure that they were aware of the services they were eligible for, should they need them.

Because I, I, there’s a process when you get discharged and they speed that process up. I do not know if you’re going to be working with veterans [but if you do] you’ll hear that a lot. They do not give you any information when they’re getting you out, they just want you stamped out and gone as fast as possible. (Participant 3009)

Fear of negative consequences of seeking care.

Several veterans reported that they did not seek mental health services, in some cases for years, because of concerns about negative consequences. While study participants were still in the military, these issues were of particular concern, because they feared that seeking care might risk their military careers. One veteran, who noticed psychiatric symptoms prior to separation, discussed his fear of seeking help.

It was difficult to seek that kind of treatment … it could have potentially affected my career had I decided to stay in. I mean depending on what you disclose in seeking treatment like that it can make you nondeployable. And if you’re nondeployable then you get kicked out of the service. (Participant 1019)

Personal beliefs about mental health treatment.

Internal stigmatization (i.e., negative beliefs about mental health treatment and the people who seek it) also served as a barrier to accessing care. Even if veterans were hearing from others that they should seek help, these personal beliefs were often powerful deterrents to care.

Well I was out of control, couldn’t keep no job, and I was not sleeping at night. And I had lost a lot of weight and my mother told me to go get me some help. … I really didn’t want to come because I always heard [mental health clinic] it was crazy people up here so I was not wanting to come up here [to the mental health clinic]. (Participant 1002)

Input from family and friends.

Veterans often mentioned interactions with family and friends as the impetus for seeking treatment. These interactions frequently came in the form of demands that the veteran get help (from spouses or partners), or suggestions that accessing services might help the veteran feel better (from other veterans). For example, when asked why he decided to seek help, one veteran commented:

… basically it was my wife told me I needed to get help or they were leaving. ‘Cause I, she would wake up I would be, you know, in the corner, you know, with a knife in my hand crying ah, you know, where the slightest little thing with my kids I would just explode at them. You know so … I was starting to drink more and … you know, just accumulation of things … [but] the biggest thing was her saying get help or we’re gone. (Participant 2015)

Another reported it was not his wife, but a fellow veteran who influenced him to seek treatment.

My uncle he was … he’s a veteran and told me I just needed to come up here and he just kept telling me I needed to come to the VA. He was like, boy you’ve got problems you need to come up there. (Participant 1004)

Motivation for treatment.

Whether because of fear of how they would be perceived if they sought treatment, internalized stigma about mental health issues, lack of motivation as a result of depression, or other factors, several veterans we interviewed noted that they had not sought services despite knowing both that they were struggling with mental health issues and that VA mental health care was accessible. Paradoxically, increases in symptom severity sometimes reduced motivation for seeking treatment. As one veteran noted, “Well, what I think initially makes it hard, is like you’re in this crisis mode of depression. It’s hard to get out of bed. So seeking help is way beyond that” (Participant 2029).

Pathways to Mental Health Care

In discussing their initiation of VA mental health treatment, many veterans in our sample went beyond discussing why they chose to access (or not access) care, and spoke about how they eventually became enrolled in this care. Overwhelmingly, veterans reported that, even after experiencing an onset or worsening of symptoms, and with facilitators in place, they did not initiate mental health care by contacting VA specialty mental health clinics directly. Instead, participants indicated that initial contact with these clinics was generally made through four pathways: (a) VA physical health appointments, usually in primary care; (b) the service connected disability system; (c) non-VA services (including vet centers); and (d) mandated treatment.

VA physical health appointments.

One of the main pathways discussed as an entry point to VA mental health services was through VA physical health appointments (especially—but not exclusively—through primary care). Whereas in some cases this was based on a formal referral process, in other cases it was more serendipitous (e.g., a veteran decided to investigate mental health services while he was already at the VA for an audiology appointment). Veterans noted that having mental health services offered at the same location as their physical health treatments was a facilitator for initiating psychiatric treatment:

And then once I found [the local VA clinic] I was like oh! Ok! I can come here for both my physical and my mental? Because when I first started coming here, it was for my pain to get a new doctor. And then I started with the mental health services and I went “Sweet!” It was very, very helpful to have them both collocated. (Participant, 2009)

The service-connected disability system.

Several veterans reported that their initial contact with the VA was related to seeking service-connected disability status rather than treatment. During or after the process of seeking such disability, which can include paid cash benefits (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2017), these veterans ended up receiving mental health services they would not have sought otherwise.

I didn’t even really know too much about the VA … my uncle just kept telling me I needed to come to the VA … I went up there and I didn’t know what to do … so they sent me through a few things and I filled out some papers and the next thing you know I had to go see a doctor. You know he did a physical and all that stuff … I ended up coming out with like 70% disability and stuff like that so I think 50% of it was PTSD, and that’s how I ended up getting connected with the psychiatrist. And they made an appointment for me and I went in and saw some guy and then the next thing you know he was like, “You really need to talk to a psychiatrist.” So I ended up going and talking with her and then she made some appointments and it just went from there. (Participant 1002)

Non-VA services.

A number of veterans noted that non-VA services ultimately introduced them to VA mental health services. In our sample, both vet centers and private sector care facilitated these connections, which could be made through direct referrals (e.g., one veteran was receiving suboxone treatment in the private sector and was referred to the VA because the medications would be more affordable). However, the connections were often more indirect, with the non-VA settings providing veterans with information about how to navigate the VA system. One veteran described how the vet center staff eased his transition to the VA.

[Initially I didn’t know how to navigate the VA] … there’s the fliers on the walls, but, there’s no standard way of “this is where you go.” They have a kiosk but if you have no idea what you’re doing with it, then you do not even know how to check in, so you go to the lady at the front, whomever’s there is their receptionist, and they ask you who you are and what you’re there for and you go “I don’t know what I’m here for,” and that’s the first thing, you actually have to find your way in. [But the vet center] gave me all kinds of, any information that I needed, they assisted me with getting, they told me where to go, they got me directions, they were really helpful with that because, like I said it’s vets treating vets, so they understand more. (Participant 2009)

Mandated treatment.

A small number of veterans noted that they initially entered the VA mental health system as an alternative to jail or more intensive inpatient services. For example, one veteran reported that he initiated VA substance-abuse treatment in lieu of jail time after receiving a citation for driving under the influence of alcohol. Another veteran described his choice between initiating outpatient mental health care or submitting to involuntary hospitalization: “They ended up admitting me into the psych ward, and they let me out and told me a week later I had to seek [outpatient] counseling … to stay out of the hospital” (Participant 2032).

Discussion

Our qualitative investigation into the initiation of VA mental health treatment provided rich data on what influences veterans to access this care, as well as the pathways to achieving access. These data lend themselves to a model of mental health-care access highlighting the facilitators and barriers that may encourage or impede a given veteran’s decision ultimately to engage in treatment. The model also includes common pathways to initiating this care (see Figure 1). Although other models have explored the sociocultural factors that influence care initiation (e.g., the network-episode model; Pescosolido, 2006), it is this additional attention to specific pathways that sets our model apart.

Many of our findings are consistent with previous literature on barriers and facilitators to accessing care (Fischer et al., 2016). Specifically, our findings emphasize the importance of personal motivation (Schultz, Martinez, Cucciare, & Timko, 2016), input from family and friends (Spoont et al., 2014), knowledge of available services (Wagner et al., 2015; Washington et al., 2006), internalized stigma (Pietrzak et al., 2009), and fear about the consequences of seeking care (Gorman et al., 2011; Hoge et al., 2004; Stecker, Fortney, Hamilton, & Ajzen, 2007) as impacting the initiation of VA mental health care.

In other areas, however, our findings appear to be at odds with the previous literature—or at least to not emphasize facets of access to care that have been emphasized consistently in the literature. For example, veteran interview segments in this analysis did not cite travel difficulties frequently as a barrier to initiating VA mental health care, which is particularly surprising because nearly half of our sample was comprised of rural veterans, for whom travel is often described as a primary barrier to accessing care (e.g., Buzza et al., 2011; Goins et al., 2005). This may not have been the case in our study because travel distance may be a more important barrier to continuing, rather than initiating, care. Consistent with this, separate codes (not part of this analysis) did suggest that travel difficulties were seen as barriers to ongoing care. However, it also may be that the factors influencing the initiation of mental health care are somewhat different from those associated with initiating other types of care.

One of the benefits of using a qualitative approach is the ability to uncover unexpected findings by capturing veterans’ lived experiences of accessing care. Although we set out to investigate factors that influence the initiation of care, many veterans took the opportunity to also discuss their pathways to accessing VA mental health care. Although it is possible for veterans to directly contact VA specialty mental health clinics for services, this was not the case for our sample. Instead, veterans in our sample consistently indicated that they became connected with VA mental health services through one of four pathways: VA physical health care, service-connection disability services, non-VA services including vet centers, and mandates to receive treatment. The VA already has begun to capitalize on these pathways; one component of the VA’s large-scale quality-improvement initiative for veteran access was the introduction of VA Primary Care Mental Health Integration (PC-MHI), a program that embeds mental health providers into primary care teams (Zeiss & Karlin, 2008). Since their initial inception in the late 2000s, PC-MHI services have already demonstrated improvements in facilitating mental health diagnoses and treatment engagement for veterans (Bohnert, Sripada, Mach, & McCarthy, 2016). Our findings—that primary care appointments may serve as an important gateway to mental health treatment—are therefore consistent with this body of literature on PC-MHI.

Other pathways to mental health treatment revealed in this study have been subject to less attention in previous research. For example, we were surprised to find that the service-connected disability system served as the de facto entry point to mental health treatment for some veterans in our sample. Currently, staff conducting compensation and pension examinations that help determine a veteran’s eligibility for disability compensation are instructed to inform the veterans they interview of available treatment options. However, staff who conduct these examinations are often required to conduct back-to-back comprehensive diagnostic evaluations in very short time frames, which may limit the time they have to pursue these discussions. Our results suggest that additional efforts to increase the frequency with which compensation and pension examiners discuss treatment options may help more veterans seek and receive appropriate mental health services.

Another pathway that has received less attention in the literature is that of non-VA services. In particular, in the current study, vet centers often served as a pathway to VA mental health care. Although technically part of the Veterans Health Administration, vet centers—which were established in 1979 to assist veterans and their families with adjustment difficulties—historically have maintained a degree of independence from VA medical centers to ensure confidential counseling (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2015). Although known to provide additional services (i.e., counseling, outreach, and referral) to veterans outside of the VA, little research has focused on the content of these services. Our findings suggest that both the vet centers themselves and the veterans who use their services, can provide immeasurable assistance to veterans hoping to transition to mental health care at the VA. It is possible that not all veterans who take advantage of vet centers would wish to transition to the VA. Because there is no shared medical record between the VA and the vet centers, accessing services at the latter is a method for compartmentalizing treatment. However, our findings suggest that some veterans do wish to make this transition. Therefore, working with vet-center staff may be another avenue to explore in an effort to provide these veterans with the support they need to access care.

Finally, several veterans in our study indicated that their pathway to VA mental health care was through the legal system or similar requirements. The idea of court-mandated mental health treatment for certain behaviors (e.g., partner battering, substance abuse) is not new; offenders are often assigned to treatment as a component of their sentence. Our findings suggest that, above and beyond such mandated treatment, strengthening the ability of the legal system’s representatives to connect veterans with VA mental health care may be helpful. Effectively leveraging this pathway, however, would need to account for the fact that some veterans might see such referrals as punitive even if they were not court-mandated.

Our findings should be considered within the context of the enormous strides VA has already made to improve veterans’ access to mental health care. Efforts including the introduction of PC-MHI, the mandating of regular mental health screenings (e.g., Department of Veterans Affairs, 2007), the passage of legislation aimed at reducing wait times (e.g., the Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014; Department of Veterans Affairs, 2014b); and targeted campaigns within VA hospitals designed to reduce stigma around mental health treatment (Department of Veterans Affairs, 2011) all have served to facilitate the initiation of services. Despite this, there are still veterans who would benefit from mental health care who do not initiate treatment. Our results provide guidance on what additional interventions may further facilitate mental health access for these veterans. For example, the importance of family and friends in veterans’ decisions to initiate care suggests that interventions that target the nonveteran community might be beneficial. Furthermore, organizations and individuals that provide VA mental health-care referrals (e.g., lawyers who regularly work with veterans; compensation and pension examiners) may help connect more veterans with VA mental health care if they are provided information packets that describe the mental health services VA offers, as well as the best way to access them. Although effective interventions to improve access are already in place, our findings suggest that additional outreach may be effective at further reducing the gap between veterans who could benefit from mental health treatment and those who initiate this care.

Our findings have implications for public sector mental health services outside of the VA system, as well. First, the facilitators and barriers to receiving help that we identified generally align well with previous literature (e.g., Gorman et al., 2011; Pietrzak et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2015), suggesting that our findings are likely generalizable. Therefore, interventions geared toward improving access suggested by our results (e.g., those designed to provide psychoeducation about the availability and purpose of mental health services and to normalize help seeking) may be effective in non-VA as well as VA settings. Second, the pathways to care identified in the current study may be relevant to any health system that aims to ensure that all patients needing mental health services have access to them. This would include, but would not be limited to, outpatient mental health clinics within accountable care organizations, which are ultimately incentivized not only to treat patients who are actively seeking their services, but also to make it easier for patients who are suffering from mental illness symptoms to seek treatment before a mental health crisis occurs (e.g., Bao, Casalino, & Pincus, 2013). For such clinics, partnering more closely with representatives of the legal system and physical health-care providers may be essential to streamlining access to their services.

This study has several limitations. First, our sample consisted mostly of White males. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other veteran groups. Second, we limited our sample only to veterans who had a positive screen for PTSD, AUD, or MDD. Veterans with other mental health disorders may not report the same barriers, facilitators, and pathways to mental health care. Third, because of our small sample size, it was impossible to estimate which of the pathways we identified would be the most promising to pursue to improve VA mental health access for the greatest number of veterans, and/or whether certain pathways would better suited for particular subsets of veterans (e.g., those at urban vs. rural sites). Additional research is needed to explore this possibility. Fourth, our sample consisted of veterans who were already in the VA system, and had therefore overcome existing barriers sufficiently to be using VA at least for physical health concerns. It is possible that veterans who have not been involved in the system at all may face additional access barriers that are not represented here. Finally, because our investigation focused purely on initiation of care, we cannot speak to the factors that encourage veterans to maintain engagement in care. Understanding both initiation and continued access is essential because initial access is only as good as available follow-up services. Getting people into the system, but not providing sufficient resources to treat them effectively, ultimately does them a disservice. Future research is encouraged to explore both aspects of access, as well as their interaction.

Despite these limitations, this article provides rich information about the barriers and facilitators veterans encounter when deciding whether to initiate VA mental health care. In addition, it provides information about the pathways veterans take to access this care. The findings serve to reinforce the current VA efforts (e.g., PC-MHI; the antistigmatization campaign), and suggest additional avenues to pursue. In particular, providing compensation and pension examiners, vet center staff, and representatives of the legal system detailed information about the services VA provides, as well as the methods through which these services can be accessed, may benefit a myriad of veterans who are not currently receiving VA mental health care. Future work should be undertaken to explore novel entry points to care to ensure that all veterans are able to receive the help they need and deserve.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development, CRE 12-300 (“Development and Validation of a Perceived Access Measure,” principal investigator: Jeffrey M. Pyne). James F. Burgess Jr., who passed away during the revision of this article, was an inspirational leader of this project and we are grateful to have had the opportunity to work with him. The authors would also like to thank Ellen P. Fischer and Regina L. Stanley for their invaluable contributions to this article.

Contributor Information

Michelle J. Bovin, National Center for PTSD at Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, and Boston University School of Medicine

Christopher J. Koenig, San Francisco State University and Palo Alto Healthcare system, Palo Alto, California

Kara A. Zamora, San Francisco Veterans Affairs Healthcare system, San Francisco, California

Jeffrey M. Pyne, Central Arkansas Veterans Healthcare System, North Little Rock, Arkansas, and University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Christopher J. Miller, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, and Harvard Medical School

Jessica M. Lipschitz, Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, and Harvard Medical School

Patricia B. Wright, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

James F. Burgess, Jr., Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts, and Boston University School of Public Health

References

- Bao Y, Casalino LP, & Pincus HA (2013). Behavioral health and health-care reform models: Patient-centered medical home, health home, and accountable care organization. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services & Research, 40, 121–132. 10.1007/s11414-012-9306-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnert KM, Sripada RK, Mach J, & McCarthy JF (2016). Same-day integrated mental health care and PTSD diagnosis and treatment among VHA primary care patients with positive PTSD screens. Psychiatric Services, 67, 94–100. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budzi D, Lurie S, Singh K, & Hooker R (2010). Veterans’ perceptions of care by nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians: A comparison from satisfaction surveys. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 22, 170–176. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00489.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett-Zeigler I, Zivin K, Ilgen MA, & Bohnert AS (2011). Perceptions of quality of health care among veterans with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatric Services, 62, 1054–1059. 10.1176/ps.62.9.pss6209_1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzza C, Ono SS, Turvey C, Wittrock S, Noble M, Reddy G, … Reisinger HS (2011). Distance is relative: Unpacking a principal barrier in rural healthcare. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 648–654. 10.1007/s11606-011-1762-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski AL, Milford J, Goldberg RW, Brown CH, & Dixon LB (2008). Perceived barriers to medical care and mental health care among veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 59, 921–924. 10.1176/ps.2008.59.8.921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy ME (1987). Quantitative and qualitative research: Antagonistic or complementary? Nursing & Health Care, 8, 356–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbogen EB, Wagner HR, Johnson SC, Kinneer P, Kang H, Vasterling JJ, … Beckham JC (2013). Are Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using mental health services? New data from a national random-sample survey. Psychiatric Services, 64, 134–141. 10.1176/appi.ps.004792011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EP, McSweeney JC, Wright P, Cheney A, Curran GM, Henderson K, & Fortney JC (2016). Overcoming barriers to sustained engagement in mental health care: Perspectives of rural veterans and providers. The Journal of Rural Health, 32, 429–438. 10.1111/jrh.12203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortney JC, Burgess JFJ Jr., Bosworth HB, Booth BM, & Kaboli PJ (2011). A re-conceptualization of access for 21st century healthcare. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 639–647. 10.1007/s11606-011-1806-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins RT, Williams KA, Carter MW, Spencer SM, & Solovieva T (2005). Perceived barriers to health care access among rural older adults: A qualitative study. The Journal of Rural Health, 21, 206–213. 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00084.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman LA, Blow AJ, Ames BD, & Reed PL (2011). National Guard families after combat: Mental health, use of mental health services, and perceived treatment barriers. Psychiatric Services, 62, 28–34. 10.1176/ps.62.1.pss6201_0028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, & Koffman RL (2004). Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems, and barriers to care. The New England Journal of Medicine, 351, 13–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa040603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, & Shannon SE (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15, 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PJ, Carlson KF, & Hearst MO (2010). Healthcare disparities for American Indian veterans in the United States: A population-based study. Medical Care, 48, 563–569. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181d5f9e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehle SM, Greer N, Rutks I, & Wilt T (2011). Interventions to improve veterans’ access to care: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26(Suppl. 2), 689–696. 10.1007/s11606-011-1849-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CJ, Burgess JF Jr., Fischer EP, Hodges DJ, Belanger LK, Lipschitz JM, … Pyne JM (2017). Practical application of opt-out recruitment methods in two health services research studies. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 17, 57 10.1186/s12874-017-0333-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ (2001). Improving access to care in the VA Health System: A progress report FORUM. Washington, DC: VA Health Services Research & Development. [Google Scholar]

- Muhr T (2017). ATLAS.ti [Computer software]. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software Development. [Google Scholar]

- Oppel RA Jr., & Shear MD (2014, May 28). Severe report finds VA hid waiting lists at hospitals. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/29/us/va-report-confirms-improper-waiting-lists-at-phoenix-center.html [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette P, Vogt D, Wade M, Tirone V, Greenbaum MA, Kimerling R, … Rosen CS (2011). Perceived barriers to care among Veterans Health Administration patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychological Services, 8, 212–223. 10.1037/a0024360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido BA (2006). Of pride and prejudice: The role of sociology and social networks in integrating the health sciences. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47, 189–208. 10.1177/002214650604700301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Johnson DC, Goldstein MB, Malley JC, & Southwick SM (2009). Perceived stigma and barriers to mental health care utilization among OEF-OIF veterans. Psychiatric Services, 60, 1118–1122. 10.1176/ps.2009.60.8.1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice JC, Davies ML, & Pizer SD (2014). Which outpatient wait-time measures are related to patient satisfaction? American Journal of Medical Quality, 29, 227–235. 10.1177/1062860613494750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyne JM, Kelly PA, Fischer EP, Miller CJ, Wright PB, Zamora K, … Fortney JC (2018). Perceived Access Inventory: Development of a preliminary version. Manuscript submitted for publiccation. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz NR, Martinez R, Cucciare MA, & Timko C (2016). Patient, program, and system barriers and facilitators to detoxification services in the U.S. Veterans Health Administration: A qualitative study of provider perspectives. Substance Use & Misuse, 51, 1330–1341. 10.3109/10826084.2016.1168446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoont MR, Nelson DB, Murdoch M, Rector T, Sayer NA, Nugent S, & Westermeyer J (2014). Impact of treatment beliefs and social network encouragement on initiation of care by VA service users with PTSD. Psychiatric Services, 65, 654–662. 10.1176/appi.ps.201200324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stecker T, Fortney JC, Hamilton F, & Ajzen I (2007). An assessment of beliefs about mental health care among veterans who served in Iraq. Psychiatric Services, 58, 1358–1361. 10.1176/ps.2007.58.10.1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Veteran Affairs. (2007). Vista Clinical Reminder user manual. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/vdl/documents/Clinical/CPRS-Clinical_Reminders/pxrm_2_6_um.pdf

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2014a). Accelerating access to care initiative: Fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/health/docs/052714AcceleratingAccessFactSheet.PDF

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2014b). Choice Act summary. Retrieved from https://www.va.gov/opa/choiceact/documents/Choice-Act-Summary.pdf

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2015). Vet Center Program. Retrieved from https://www.vetcenter.va.gov/index.asp

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs. (2017). Veterans Benefits Administration: Compensation. Retrieved from http://www.benefits.va.gov/compensation/

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs & Military Suicide Research Consortium. (2011). VA launches awareness campaign to reduce stigma. Retrieved from https://msrc.fsu.edu/news/va-launches-awareness-campaign-reduce-stigma

- United States Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Rural Health. (2008). Veterans rural health: Perspective and opportunities. Rockville, MD: Booz Allen Hamilton. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner C, Dichter ME, & Mattocks K (2015). Women veterans’ pathways to and perspectives on Veterans Affairs health care. Women’s Health Issues, 25, 658–665. 10.1016/j.whi.2015.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington DL, Bean-Mayberry B, Riopelle D, & Yano EM (2011). Access to care for women veterans: Delayed healthcare and unmet needs. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 26, 655–661. 10.1007/s11606-011-1772-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington DL, Yano EM, Simon B, & Sun S (2006). To use or not to use: What influences why women veterans choose VA health care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21, S11–S18. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00369.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiss AM, & Karlin BE (2008). Integrating mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs health-care system. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 15, 73–78. 10.1007/s10880-008-9100-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]