Abstract

The role of olfactory receptor 78 (Olfr78) in carotid body (CB) response to hypoxia was examined. BL6 mice with global deletion of Olfr78 manifested an impaired hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR), a hallmark of the CB chemosensory reflex, CB sensory nerve activity, and reduced intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) response of glomus cells to hypoxia (Po2 ~ 40 mmHg). In contrast, severe hypoxia (Po2 ~ 10 mmHg) depressed breathing and produced a very weak CB sensory nerve excitation but robust elevation of [Ca2+]i in Olfr78 null glomus cells. CB sensory nerve excitation evoked by Olfr78 ligands, lactate, propionate, acetate, and butyrate were unaffected in mutant mice and were smaller than that evoked by hypoxia (Po2 ~ 40mmHg). Similar results were obtained in Olfr78 null mice on a JAX genetic background. These results demonstrate a role for Olfr78 in CB responses to a wide range of hypoxia, but not severe hypoxia, and do not require either lactate or any other short-chain fatty acids.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The current study demonstrates that olfactory receptor 78 (Olfr78), a G protein-coupled receptor, is an integral component of the hypoxic sensing mechanism of the carotid body to a wide range of low oxygen levels, but not severe hypoxia, and that Olfr78 participation does not require either lactate or any other short-chain fatty acids, proposed ligands of Olfr78.

Keywords: carotid body, carotid body chemosensory reflex, G protein-coupled receptors, glomus cells, hypoxic ventilatory response, oxygen sensing

INTRODUCTION

Olfactory receptors (Olfrs) are G protein-coupled receptors for detecting smell sensation (Schild and Restrepo 1998). Although Olfrs were originally described in olfactory neurons, emerging evidence suggests that tissues other than olfactory neurons also express some Olfrs (Maßberg and Hatt 2018). Carotid bodies (CB) are the sensory organs for detecting O2 levels in arterial blood (Kumar and Prabhakar 2012). Recent studies demonstrated high abundance of Olfr 78 (also known as MOL 2.3 and MOR 18-2) gene expression in glomus cells, the primary O2-sensing cells of the CB (Chang et al. 2015).

Mice deficient in Olfr78 exhibit blunted hypoxia-evoked CB sensory nerve excitation and intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) elevation in glomus cells, and these effects were associated with reduced hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR), a hallmark of the CB chemosensory reflex (Chang et al. 2015). It was proposed that hypoxic sensing by the CB involves Olfr78 activation by lactate, whose abundance is increased in the blood during hypoxia (Chang et al. 2015). However, a subsequent study reported that HVR and glomus cell [Ca2+]i and neurotransmitter secretory responses to severe hypoxia and lactate were unaltered in Olfr78 knockout mice, thereby questioning the role of Olfr78-lactate signaling in hypoxic response of the CB (Torres-Torrelo et al. 2018). Olfr78-lactate signaling is potentially a novel mechanism in CB chemoreception. However, progress in this area is hampered because of the existing controversy. Consequently, the overarching goal of the current study is to investigate the discrepancy between the earlier studies. Chang et al. (2015) studied the role of Olfr78 in CB response to relatively modest hypoxia, whereas Torres-Torrelo et al. (2018) employed severe hypoxia (Po2 ~ 10–15 mmHg) to assess the role of Olfr78 in glomus cell responses to low O2. The current study tested the hypothesis that the participation of Olfr78 in CB response to low O2 depends on the severity of hypoxia.

METHODS

Preparation of Animals

Experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Chicago. Experiments were performed on age-matched adult wild-type (WT) and Olfr78 null mice on a C57BL/6 background (Olfr78/BL6; a gift from Dr. J. Pluznick, Johns Hopkins University). These mice were originally developed by Peter Mombaerts at the Rockefeller University, which were then bought from JAX and backcrossed onto C57BL/6. Olfr78 mice on a 129P2/OlaHsd background (Olfr78/JAX) were a gift from Dr. A. Chang, The University of California, San Francisco).

Measurements of Breathing

Whole body plethysmography.

Ventilation was monitored by whole body plethysmograph (Buxco, DSI, St. Paul, MN). Oxygen consumption (V̇o2) and CO2 production (V̇co2) were determined by the open circuit method as described previously (Frappell et al. 1992). The following equations were used to calculate V̇o2 and V̇co2: V̇o2 = V̇e (−)/(1−) and V̇co2 = V̇e (−)/(1−), wherein i denotes ingoing gas and e denotes outgoing gas, V̇ is the flow, and F is fractional concentration (Frappell et al. 1992). Breathing was recorded while the mice breathed 21%, 12%, or 10% O2 balanced with N2. Each gas challenge was given for 5 min. O2 consumption and CO2 production were measured at the end of each 5-min challenge. To determine the ventilatory response to CO2, baseline ventilation was obtained while mice breathed 100% O2 followed by a hypercapnic challenge with 5% CO2-95% O2. Sighs, sniffs, and movement-induced changes in breathing were monitored and excluded from the analysis. All recordings were made at an ambient temperature of 25 ± 1°C. Minute ventilation [Ve = tidal volume (VT) × respiratory rate (RR)] was calculated and normalized for body weight and expressed as a ratio to O2 consumption (Ve/Vo2).

Analysis of breathing irregularity score.

The breathing irregularity score was determined by the following formula: absolute (TTOTn−TTOTn+1)/(TTOTn+1) × 100%, where TTOT represents total duration of a breath as described previously (Derecki et al. 2012; Garg et al. 2013).

Measurements of phrenic nerve activity.

Mice were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of urethane (1.2 g/kg). Supplemental doses (10% of the initial dose of anesthetic) were given when corneal reflexes or responses to toe pinches were observed. Animals were placed on a warm surgical board, and a tracheotomy was performed through a midline neck incision. The trachea was cannulated, and mice were allowed to breathe spontaneously. Core body temperature was monitored by a rectal thermistor probe and maintained at 37 ± 1°C by a heating pad. The phrenic nerve was isolated unilaterally at the level of the C3 and C4 spinal segments, cut distally, and placed on bipolar stainless steel electrodes. Integrated efferent phrenic nerve activity was monitored as an index of respiratory neuronal output. The electrical activity was filtered (bandpass, 30 Hz–10 kHz), amplified (P511K; Grass Instrument, West Warwick, RI), and passed through Paynter filters (time constant of 100 ms; CWE Inc.) to obtain a moving average signal. Data were collected with a sampling rate of 20 kHz and stored in a computer for further analysis (PowerLab/8P; AD Instruments Pty Ltd, Australia). Phrenic nerve activity (bursts/min; an index of respiratory rate), tidal phrenic nerve activity (in arbitrary units, A.U.), and minute neuronal respiration (MNR = RR × tidal phrenic nerve activity) were analyzed. The effects of hypoxia (12% O2–balance N2) and hypercapnia (5% CO2-95% O2) on phrenic nerve activity were determined. Gases were administered through a needle placed in the tracheal cannula, and gas flow was controlled by a flow meter. For hypoxic responses, baseline phrenic nerve activity was monitored while the animals breathed room air for 3 min. Subsequently, inspired gas was switched to 12% O2 for 3 min. The duration of 3 min for hypoxia was chosen because a longer duration of hypoxic exposure (>5 min) in anesthetized mice leads to hypotension, which confounds interpretation of results. For the hypercapnic response, 3 min of 5% CO2-95% O2 was preceded by exposure to 100% O2 for 3 min. At the end of the experiment, mice were killed by overdose of urethane (>3.6 g/kg ip).

Measurements of Arterial Blood Gases

Arterial blood (0.1 mL) was collected in the anesthetized mice while they were breathing room air or exposed to hypoxia (12%O2) via a catheter (PE-10) inserted into the femoral artery. Blood gases [arterial partial pressures of oxygen () and carbon dioxide ( and pH] were determined by a blood gas analyzer (ABL-80; Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Hyperoxic Challenge (Dejours test)

Dejours test was performed on anesthetized mice. Baseline phrenic nerve activity was recorded while animals breathed 21% O2 followed by 100% O2 for 30 s. Respiratory variables were analyzed during 21% O2 breathing and during the last 20 s of hyperoxia (the initial 10 s were excluded because of dead space in the respiratory circuit).

Recording of CB Sensory Nerve Activity

Sensory nerve activity from CB ex vivo was recorded as previously described (Peng et al. 2006). Briefly, CBs along with the sinus nerves were harvested from anesthetized mice, placed in a recording chamber (volume 250 μL), and superfused with warm physiological saline (35°C) at a rate of 3 mL/min. The composition of the medium was (in mM) 125 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 d-glucose, and 5 sucrose. The solution was bubbled with 21% O2-5% CO2. Hypoxic challenges were achieved by switching the perfusate to physiological saline equilibrated with desired levels of O2. Severe hypoxia was accomplished by degassing the medium (37°C) for 5 h, followed by continuous bubbling with 95% N2 and 5% CO2 throughout the experiment. Oxygen levels in the medium were continuously monitored by a platinum electrode placed next to the CB, using a polarographic amplifier (model 1900; A-M Systems, Sequim, WA). To facilitate recording of clearly identifiable action potentials, the sinus nerve was treated with 0.1% collagenase for 5 min. Action potentials (1–3 active units) were recorded from one of the nerve bundles with a suction electrode (band pass; 30 Hz–10 kHz, sampling rate 20 kHz) and stored in a computer via a data acquisition system (PowerLab/8P). “Single” units were selected based on the height and duration of the individual action potentials using the spike discrimination module.

Primary Cultures of Glomus Cells

Primary cultures of glomus cells were prepared as described previously (Makarenko et al. 2012). Briefly, CBs were harvested from urethane (1.2 g/kg ip)-anesthetized mice. Glomus cells were dissociated using a mixture of collagenase P (2 mg/mL; Roche), DNase (15 μg/mL; Sigma), and bovine serum albumin (BSA; 3 mg/mL; Sigma) at 37°C for 20 min, followed by a 15-min incubation in medium containing DNase (30 μg/mL) only. Cells were plated on collagen (type VII; Sigma)-coated coverslips and maintained at 37°C in a 7% CO2 + 20% O2 incubator overnight (~18 h). The growth medium consisted of F-12K medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum, insulin-transferrin-selenium (ITS-X; Invitrogen), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine mixture (Invitrogen).

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

Glomus cells were incubated in Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) with 2 μM fura-2 AM and 1 mg/mL albumin for 30 min and then washed in a fura-2-free solution for 30 min at 37°C. The coverslip was transferred to an experimental chamber for determining the changes in [Ca2+]i. Background fluorescence was obtained at 340- and 380-nm wavelengths from an area of the coverslip devoid of cells. On each coverslip, glomus cells were identified by their characteristic clustering, and individual cells were imaged with a Leica microscope and Hamamatsu camera (model C11440) using the software HC Image (version 4.5.1.3). Image pairs (one at 340-nm and the other at 380-nm wavelength, respectively) were obtained every 2 s by averaging 16 frames at each wavelength. Data were continuously collected throughout the experiment. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the cell data obtained at the individual wavelengths. Fluorescence intensity of the image obtained at 340 nm was divided by that of the at 380 nm to obtain a ratiometric image. Ratios were converted to free [Ca2+]i using calibration curves constructed in vitro by adding fura-2 (50 μM free acid) to solutions containing known concentrations of Ca2+ (0–2,000 nM). The recording chamber was continually irrigated with warm solution (31°C) from gravity-fed reservoirs. The composition of the medium was the same as that employed for recording CB sensory activity (described above).

Chemicals

Sodium lactate, sodium acetate, sodium propionate, and sodium butyrate were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. All solutions were prepared fresh in physiological saline at the time of the experiment. Equal molar amounts of sodium chloride in physiological saline were replaced with each substance tested.

Data Analysis

The following variables were analyzed in unanesthetized mice: tidal volume (Vt; μL), respiratory rate (RR; breaths/min); minute ventilation (Ve; mL·min·g body wt), O2 consumption (Vo2; mL/min), and CO2 production (Vco2; mL/min). In agreement with other investigators (Dauger et al. 1998; Tankersley et al. 1993, 1994), we also found that breathing is unstable in unanesthetized mice due to movement, sniffing, and exploratory behaviors. Therefore, 15–20 consecutive stable breaths per minute were chosen for analysis of respiratory variables during breathing of room air and during 5 min of hypoxia and CO2 challenges. Vt and Ve were normalized to the body weight of the animals. Each data point represents the average of two trials in a given animal for a given gas challenge. In anesthetized animals, the following respiratory variables were analyzed: respiratory rate (phrenic bursts/min), amplitude of the integrated tidal phrenic nerve activity (arbitrary units, a.u.), and minute neural respiration [MNR; number of phrenic bursts/min (RR) × amplitude of integrated tidal phrenic nerve activity (a.u.)]. CB sensory activity (discharge from “single” units) was averaged during 3 min of baseline and during the entire 3 min of hypoxic challenge and expressed as impulses per second unless otherwise stated. All data are presented as box-whisker plots with individual data points, unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was assessed by Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, or two‐way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Tukey’s test using SigmaPlot (version 11). P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Hypoxic Ventilatory Response of Olfr78 Null Mice

The carotid body chemosensory reflex mediates the hypoxic ventilatory response (HVR) (Kumar and Prabhakar 2012). HVR was determined by two approaches: one by monitoring breathing in unanesthetized mice by whole body plethysmography and the other by measuring phrenic nerve activity in anesthetized mice.

Unanesthetized mice.

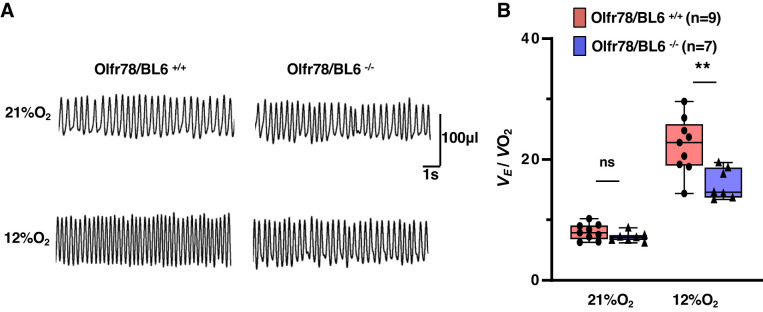

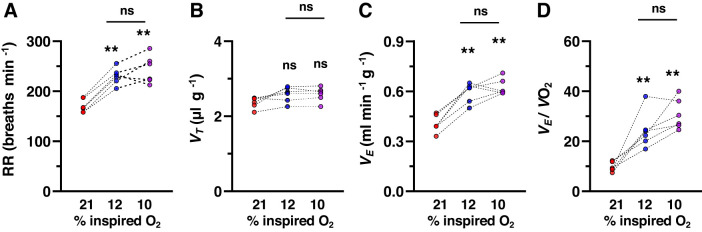

Baseline respiration was monitored while mice were breathing room air followed by breathing 12% O2 (hypoxia) for 5 min. We chose 5 min of hypoxic exposure because longer than 5 min of low O2 exposure lowers body temperature in mice (Kline et al. 1998). Figure 1A illustrates an example of breathing responses to 12% O2 in a wild-type and mutant mice. Absolute values of respiratory variables during breathing of room air or 12% O2 for both genotypes are presented in Supplemental Table S1 (see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3). Olfr78 null mice manifested irregular breathing during room air breathing (Supplemental Fig. S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3). Changes in minute ventilation (Ve) (breathing rate × tidal volume) were normalized to body weight and O2 consumption (Vo2), because body metabolism is an important determinant of HVR (Frappell et al. 1992). Mutant mice manifested reduced Ve/Vo2 while breathing 12% O2 as compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Table S1; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3). Chang et al. (2015) as well as Torres-Torrelo et al. (2018) examined the breathing responses to 10% O2 as opposed to 12% O2 used in the current study. Therefore, we compared HVR evoked by 12% and 10% O2 in additional wild-type mice (n = 6). Although HVR tend to be higher with 10% O2, the difference was not statistically significant compared to that with 12% O2 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Hypoxic ventilatory responses (HVR) of unanesthetized wild-type (Olfr78/BL6+/+) and olfactory receptor 78 null (Olfr78/BL6−/−) mice. A: representative plethysmograph tracings of breathing in unanesthetized mice breathing room air (21% O2) and 12% O2 (hypoxia; for 5 min). B: box-whisker plots with individual data points; n = no. of mice. Data are minute ventilation (Ve) normalized to body weight and oxygen consumption (Ve/Vo2) for Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice, analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Tukey’s test (room air, P = 0.56; hypoxia, P < 0.001; F1,15= 10.543, df = 1). **P < 0.01; ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of breathing responses to 10% and 12% inspired O2 levels in wild-type mice. Breathing was measured by whole body plethysmography in unanesthetized mice (n = 6) breathing room air (21% O2) followed by 12% and 10% O2. Each level of hypoxia was given for 5 min. Data are respiratory rate (RR; breaths/min; A), tidal volume (Vt; µL/g body wt; B), minute ventilation (Ve) normalized to body weight (C), and oxygen consumption (Ve/Vo2; D) from individual mice. A: 21% vs. 12% O2 (P < 0.001), 21% vs. 10% O2 (P < 0.001), 12% vs. 10% O2 (P = 0.504). B: 21% vs. 12% vs. 10% O2 (P = 0.097). C: 21% vs. 12% O2 (P < 0.001), 21% vs. 10% O2 (P < 0.001), and 12% vs. 10% O2 (P = 0.567). D: 21% vs. 12% O2 (P = 0.001), 21% vs. 10% O2 (P < 0.001), and 12% vs. 10% O2 (P = 0.147). **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test; ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

Anaesthetized mice.

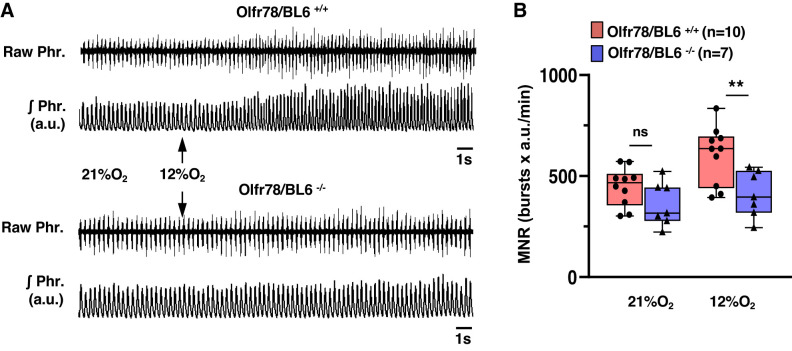

Breathing was irregular in unanesthetized mice due to sniffing and exploratory behaviors (Supplemental Fig. S2; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3). Therefore, analysis of HVR required choosing segments of 15–20 consecutive stable breaths every minute, which is a potential limitation of plethysmograph approach. To circumvent this limitation, HVR was determined by monitoring phrenic nerve activity as an index of breathing in anesthetized wild type and mutant mice. Examples of phrenic nerve response to 12% O2 and a summary of minute neural respiration (MNR = phrenic bursts/min × tidal amplitude in arbitrary units) are presented in Fig. 3, A and B. Hypoxia increased MNR in wild-type mice, and these responses were attenuated by ~60% in Olfr78 null mice (Fig. 3B). To assess whether the degree oxygenation accounts for differing HVR between wild-type and mutant mice, arterial blood gases were determined during breathing of room air or 12% O2. As shown in Table 1, arterial blood O2 values in room air and in 12%O2 were comparable between both genotypes.

Fig. 3.

Phrenic nerve responses to hypoxia in anesthetized wild-type (Olfr78/BL6+/+) and olfactory receptor 78 null (Olfr78/BL6−/−) mice. A: example of phrenic nerve activity in anesthetized mice breathing room air (21% O2) and 12% O2 (arrows). Raw Phr., action potentials of the phrenic nerve; ʃPhr., integrated phrenic nerve activity (in arbitrary units, a.u.). B: box-whisker plots with individual data points; n = no. of mice in each group. Data of Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Tukey’s test (room air, P = 0.158; hypoxia, P = 0.004; F1,16 = 5.972, df = 1). MNR, minute neural respiration. **P <0.01; ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

Table 1.

Arterial blood gases in anesthetized wild-type and Olfr78/BL6−/− mice

| Olfr78/BL6+/+ |

Olfr78/BL6−/− |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21% O2 | 12% O2 | 21% O2 | 12% O2 | |

| , mmHg | 91 ± 5 | 38 ± 2 | 95 ± 8 | 39 ± 4ns |

| , mmHg | 38 ± 3 | 31 ± 2 | 37 ± 3 | 29 ± 3ns |

| pH | 7.30 ± 0.01 | 7.23 ± 0.03 | 7.33 ± 0.02 | 7.27 ± 0.02ns |

Values are means ± SE of arterial blood gases and arterial pH in anesthetized wild-type (Olfr78/BL6+/+; n = 5) and olfactory receptor 78 null mice (Olfr78/BL6−/−; n = 5). , partial pressure of arterial blood O2; , partial pressure of arterial CO2. Data of Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice were analyzed by Mann-Whitney rank-sum test (, P = 1.000; , P = 0.313; pH, P = 0.310).

Not significant (P > 0.05).

To determine whether Olfr78 deficiency selectively affects HVR, breathing responses to CO2 were examined. Mice were challenged with hyperoxic CO2 (95% O2 + 5% CO2), which stimulates breathing through central chemoreceptors involving another G protein-coupled receptor, GPR4 (Kumar et al. 2015). Breathing responses to CO2 measured either by plethysmography or by phrenic nerve activity were unaltered in Olfr78 null mice (Supplemental Fig. S3 and Supplemental Table S2; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3).

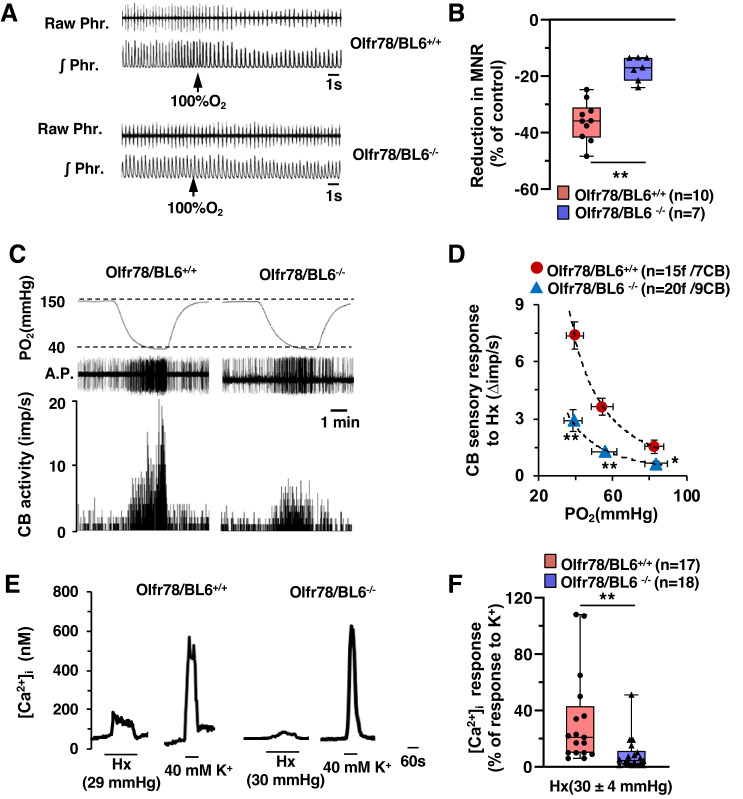

Impaired carotid body function in Olfr78 null mice.

CB function in wild-type and mutant mice was assessed by three approaches: 1) monitoring breathing responses to brief hyperoxia (Dejours test; Dejours 1962), which is an established assay for determining peripheral chemoreception, especially the CB sensitivity to O2 in human subjects (Dejours 1962) and rodents (Kline et al. 1998); 2) recording CB sensory nerve activity; and 3) determining [Ca2+]i responses of CB glomus cells to hypoxia.

Breathing responses to brief hyperoxia (Dejours test).

Baseline phrenic nerve activity was recorded in anesthetized mice during breathing of room air followed by 30 s of hyperoxia (100% O2). Phrenic nerve activity was analyzed during the last 20 s of the hyperoxic challenge (the initial 10 s were excluded because of the dead space in the breathing circuit). Wild-type mice manifested a significantly greater depression of minute neural respiration in response to hyperoxia compared with mutant mice (Fig. 4, A and B).

Fig. 4.

Impaired carotid body (CB) sensitivity to O2 in olfactory receptor 78 (Olfr78)-deficient mice. A: phrenic nerve response to brief hyperoxia was tested (Dejours test). Example shows phrenic nerve responses to 30 s of 100%O2 (arrows) in spontaneously breathing, anesthetized mice. Raw Phr., action potentials of the phrenic nerve; ʃPhr., integrated phrenic nerve activity. B: box-whisker plots with individual data points; n = no. of mice. Data are minute neural respiration (MNR) responses to hyperoxia presented as a percentage of baseline breathing in room air (%control) for Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice (P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney rank-sum test). C: examples of CB sensory nerve response to hypoxia (medium Po2 ~ 40 mmHg) in Olfr78/BL6+/+ and Olfr78/BL6−/− mice. Top, Po2 (mmHg) in the medium as measured by an O2 electrode placed close to the CB; middle, raw action potentials (A.P.); bottom, integrated action potential frequency presented as impulses per second (imp/s). D: average data (means ± SE) of CB sensory nerve responses to graded hypoxia presented as stimulus-evoked response minus baseline sensory nerve activity (Δimp/s); n = no. of fibers (f)/no. of CBs. Data of Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Tukey test (left to right: P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P = 0.037, respectively; F1,34 = 35.942, df = 1). E: examples of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) responses of glomus cells to hypoxia (Hx; mmHg) and 40 mM KCl (K+). Po2 values in parentheses represent O2 levels in the medium irrigating the cells. F: box-whisker plots with individual data points showing [Ca2+]i responses to hypoxia; n = no. of glomus cells. Data are responses to hypoxia minus baseline levels (Δ[Ca2+]i; nM) presented as a percentage of [Ca2+]i responses to 40 mM K+ for Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice (P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney rank-sum test). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

CB sensory nerve responses to hypoxia.

Sensory nerve activity was recorded from ex vivo CBs, to exclude confounding influence from changes in blood pressure, which are commonly encountered in in vivo preparations. Stimulation of breathing elicited by 12% O2 resulted in a arterial Po2 of 39 mmHg (Table 1). Therefore, CB sensory nerve responses to graded hypoxia with a maximum severity of Po2 ~ 40 mmHg were examined. An example illustrating the effect of CB sensory nerve responses to medium Po2 of 40 mmHg and responses to a range of bathing medium Po2 values are shown in Fig. 4, C and D. The magnitude of sensory nerve response to a given Po2 value was significantly less in mutant mice compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 2D).

[Ca2+]i response of glomus cells to hypoxia.

Wild-type glomus cells manifested elevated [Ca2+]i in response to hypoxia (Po2 ~ 30–40 mmHg), and this effect was markedly attenuated in Olfr78 null cells (Fig. 4, E and F). However, [Ca2+]i elevations produced by 40 mM KCl, a nonselective depolarizing stimulus, were comparable in glomus cells of both genotypes (Fig. 4, E and F).

Responses to severe hypoxia.

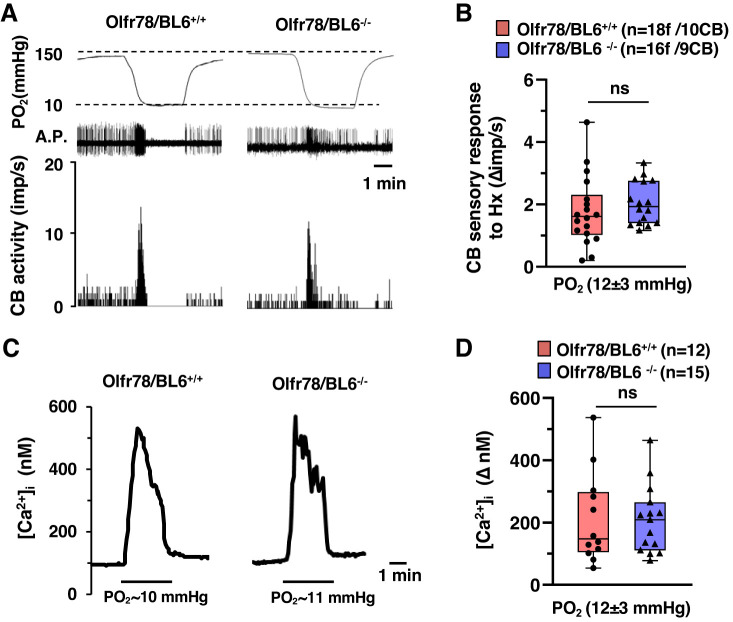

Glomus cell responses to severe hypoxia (Po2 ~ 10–15 mmHg) were unaltered in Olfr78 null mice (Torres-Torrelo et al. 2018). To assess whether altered CB function in Olfr78 null mice depends on the magnitude of hypoxia, CB sensory nerve activity and [Ca2+]i changes of glomus cells were examined in response to severe hypoxia (Po2 ~ 10–15 mmHg). Severe hypoxia produced a brief but modest stimulation of the CB sensory nerve activity and a robust [Ca2+]i elevation, and these responses were unaltered in Olfr78 null mice (Fig. 5, A–D). Unlike 12% O2, which stimulated breathing, severe hypoxia produced respiratory depression in both wild-type and Olfr78 mutant mice (Supplemental Fig. S4; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3).

Fig. 5.

Carotid body (CB) sensory nerve and glomus cell response to severe hypoxia. A: examples of CB sensory nerve response to severe hypoxia (medium Po2 ~ 10 mmHg) in wild-type (Olfr78/BL6+/+) and olfactory receptor 78 null (Olfr78/BL6−/−) mice. Top, Po2 (mmHg) in the superfusion medium measured by an O2 electrode placed close to the CB; middle, raw action potentials (A.P.); bottom, integrated action potential frequency presented as impulses per second (imp/s). B: box-whisker plots with individual data points showing CB sensory responses to severe hypoxia; n = no. of fibers (f)/no. of CBs. Data are responses to hypoxia minus baseline levels (Δimp/s) for Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice (P = 0.234, Mann-Whitney rank-sum test). C: examples of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) response of glomus cells to severe hypoxia in mice from both genotypes. D: box-whisker plots with individual data points showing [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells to severe hypoxia (n = no. of glomus cells) for Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice (P = 0.942, Mann-Whitney rank-sum test). ns, Not significant (P > 0.05).

Carotid Body Responses to Lactate

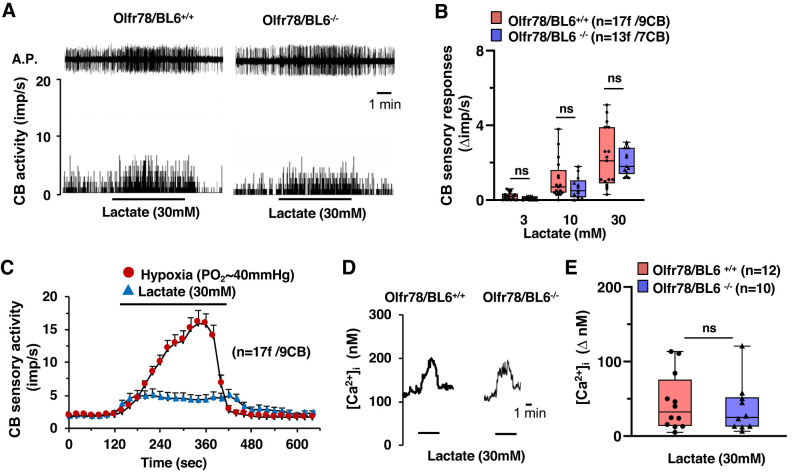

It was proposed that activation of Olfr78 by lactate mediates hypoxia-evoked excitation of CB sensory nerve activity (Chang et al. 2015), a possibility that was questioned in a subsequent study (Torres-Torrelo et al. 2018). Therefore, we determined the effects of lactate on CB sensory nerve activity and [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells. Lactate increased CB sensory nerve activity in a dose-dependent manner in both wild-type and mutant mice (Fig. 6, A and B). The magnitude of CB sensory nerve excitation evoked by lactate (30 mM, maximum concentration used in this study) was far less than that caused by hypoxia (Po2 ~ 40mmHg) (Fig. 6C). [Ca2+]i elevation of glomus cells by lactate was indistinguishable between wild-type and Olfr78 null mice (Fig. 6, D and E).

Fig. 6.

Carotid body (CB) sensory nerve and glomus cell response to lactate in wild-type (Olfr78/BL6+/+) and olfactory receptor 78 null (Olfr78/BL6−/−) mice. A: example of CB sensory nerve response to 30 mM lactate in Olfr78/BL6+/+ and Olfr78/BL6−/− mice. Top, action potentials (A.P.) of the sinus nerve; bottom, integrated action potential frequency presented as impulses per second (imp/s). B: box-whisker plots with individual data points showing dose-dependent CB sensory nerve response to lactate (Δimp/s). Data of Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Tukey test (left to right: P = 0.752, P = 0.2, and P = 0.577, respectively; F1,29 = 0.901, df = 1). C: comparison of CB sensory nerve response to hypoxia (Po2 ~ 40 mmHg) and 30 mM lactate in Olfr78/BL6+/+ mice; n = no. of fibers (f)/no. of CBs. D and E: examples of intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) responses of Olfr78/BL6+/+ and Olfr78/BL6−/− glomus cells to 30 mM lactate (D) and box-whisker plots with individual data points showing [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells to 30 mM lactate (E) for Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice (P = 0.767, Mann-Whitney rank-sum test). ns, Not significant (P > 0.05).

Carotid Body Activation by Short-Chain Fatty Acids

Short-chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate are also ligands for Olfr78 (Pluznick 2016; Pluznick et al. 2013). We tested whether Olf78 null mice exhibit altered CB sensory nerve responses to short-chain fatty acids. To this end, CB sensory nerve responses to increasing concentrations of acetate, propionate, and butyrate were examined. Similarly to lactate, all three short-chain fatty acids produced dose-dependent stimulation of the CB sensory nerve activity, and the magnitude of excitation was comparable between both genotypes (Fig. 7, A–C).

Fig. 7.

Carotid body (CB) sensory nerve response to acetate, propionate, and butyrate in wild-type (Olfr78/BL6+/+) and olfactory receptor 78 null (Olfr78/BL6−/−) mice. A–C: box-whisker plots with individual data points showing CB sensory nerve response, presented as change in impulses per second (Δimp/s), to increasing concentrations of acetate (A), propionate (B), and butyrate (C) in Olfr78/BL6+/+ and Olfr78/BL6−/− mice; n = no. of fibers (f)/no. of CBs. Data of Olfr78/BL6+/+ vs. Olfr78/BL6−/− mice were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Tukey’s test (A, left to right: P = 0.858, P = 0.224, and P = 0.067, respectively; F1,34 = 2.484, df = 1; B, left to right: P = 0.716, P = 0.369, and P = 0.061, respectively; F1,30 = 1.979, df = 1; C, left to right: P = 0.865, P = 0.607, and P = 0.606, respectively; F1,26 = 0.532, df = 1). ns, Not significant (P > 0.05).

Studies on Olfr78 Null Mice Raised on JAX Genetic Background

To test whether genetic background influences Olfr78 null mice responses to hypoxia, studies were performed on Olfr78 null mice raised on JAX instead of a BL6 genetic background. Olfr78/JAX−/− mice exhibited 1) impaired HVR measured either by plethysmography or by phrenic nerve activity (Supplemental Fig. S5 and Supplemental Table S3; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3), 2) attenuated respiratory depression by brief hyperoxia, 3) reduced CB sensory nerve activity to a range of medium Po2 values, and 4) glomus cell [Ca 2+]i responses to Po2 ~ 30 mmHg (Supplemental Fig. S6; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3). However, CB sensory nerve and glomus cell responses to severe hypoxia (Po2 ~ 10–15 mmHg) were unaltered in Olfr78/JAX−/− mice (CB sensory nerve activity: wild-type vs. Olfr78/JAX null mice, +1.8 ± 0.28 vs. +2.0 ± 0.30 impulses/s, n = 15 and 16 fibers, respectively, P = 0.594, Mann–Whitney rank-sum test; [Ca2+]i responses of glomus cells: wild-type vs. Olfr78/JAX, +203 ± 33 vs. +226 ± 27 nM, n = 13 and 15 cells, respectively, P = 0.629, Mann–Whitney rank-sum test). Likewise, CB sensory nerve responses of Olfr78/JAX−/− mice to 30 mM lactate, acetate, propionate, and butyrate were comparable to those of wild-type mice (Supplemental Fig. S7, A–C; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3).

DISCUSSION

The present results demonstrate attenuated HVR, a hallmark of the CB chemosensory reflex, in unanesthetized Olfr78 null mice as measured by whole body plethysmography. The reduced HVR was primarily due to absence of increased respiratory rate and is reflected in a ~30% reduction in minute ventilation (Ve) normalized to body weight and oxygen consumption (Vo2). The attenuated HVR was seen in Olfr78 null mice generated on either a BL6 or JAX genetic background, thereby negating any potential confounding influence from background strains. Using the same plethysmograph approach, on one hand, Chang et al. (2015) reported complete absence of HVR in Olfr78 null mice, and on the other, Torres-Torrelo et al. (2018) found unaltered HVR. Both Chang et al. (2015) and Torres-Torrelo et al. (2018) examined the effects of 10% inspired O2, whereas the current study employed 12% O2. It is conceivable that the differences in HVR observed in the current study are due to less severe hypoxia compared with earlier studies (Chang et al. 2015; Torres-Torrelo et al. 2018). Such a possibility appears unlikely, because the magnitude of HVR evoked by 12% O2 was not significantly different from that elicited by 10% O2 breathing (Fig. 2).

In small animals such as mice, metabolism is a major determinant of HVR (Frappell et al. 1992). Hypoxia decreases body metabolism (Vo2), and as a consequence, the response of minute ventilation (Ve) to hypoxia either remains unaltered or decreases (Frappell et al. 1992). Given that neither Chang et al. (2015) nor Torres-Torrelo et al. (2018) normalized HVR to changes in metabolism, it remains uncertain whether differing breathing responses reported in these studies were due to changes in metabolism. Alternatively, loss of Olfr78 might have induced compensatory changes either in the CB or in the central nervous system, as suggested by Chang et al. (2018). Furthermore, Torres-Torrelo et al. (2018) analyzed breathing by integrating respiratory rate. Consistent with findings of other investigators (Dauger et al. 1998; Tankersley et al. 1993, 1994), breathing was irregular in our unanesthetized mice, conceivably due to sniffing and exploratory behaviors (Supplemental Fig. S2; see https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11867919.v3). As a consequence, it was technically challenging to integrate the respiratory rate in unanesthetized mice. This limitation necessitated choosing segments of 15–20 consecutive stable breaths every minute for the analysis of HVR.

It may be argued that our HVR analysis is biased because of our choice of picking stable breaths. Therefore, we further validated HVR analysis by recording phrenic nerve activity as an index of breathing in anesthetized mice. Notwithstanding the limitation of anesthesia, our results showed a near 60% suppression of HVR in anesthetized Olfr78 null compared with wild-type controls. The greater suppression of HVR in anesthetized mice (~60%) is likely due to anesthesia as compared with that in unanesthetized mice (~30%). The reduced HVR in anesthetized Olfr78 null mice was due to attenuated increases in tidal volume as well as respiratory rate compared with that in wild-type controls. Moreover, the impaired HVR in mutant mice is unlikely due to differences in oxygenation of arterial blood, because values were comparable during breathing of room air and 12% O2 between both genotypes (Table 1). In striking contrast, breathing stimulation by hyperoxic CO2, which is primarily due to activation of the central chemoreceptors, was unaffected in Olfr78 null mice, suggesting that Olfr78 null mice manifest selective impairment of HVR, which is a hallmark of the CB chemosensory reflex.

The following observations demonstrate Olfr78 null mice manifest impaired CB responses to hypoxia: 1) attenuated breathing response to brief hyperoxia (Dejours test), an established assay for measuring peripheral chemoreception, especially the CB sensitivity to O2 in humans (Dejours 1962) and in experimental rodents (Kline et al. 1998), 2) reduced CB sensory nerve excitation to a range of hypoxic levels, and 3) impaired [Ca2+]i elevation by hypoxia in glomus cells, the primary O2-sensing cells of the CB. It is generally regarded that a decrease in arterial blood Po2 is the stimulus for CB sensory nerve excitation (Kumar and Prabhakar 2012). CB sensory nerve response to graded hypoxia is long been considered as a “standard” measure of hypoxia response of the CB (Prabhakar 2006). We tested the effects of graded hypoxia with an upper limit of Po2 ~ 40 mmHg, because 12% O2, which stimulated breathing, resulted in an arterial blood Po2 of ~40 mmHg. CBs of Olfr78 null mice manifested reduced sensory nerve excitation to graded hypoxia and markedly reduced glomus cell [Ca2+]i elevation by Po2 of 30–40 mmHg, suggesting a role for Olfr78 in the hypoxic response of the CB.

On the other hand, Torres-Torrelo et al. (2018) studied the effects of severe hypoxia (Po2 ~10–15 mmHg) on glomus cell [Ca2+]i changes and transmitter secretion and found that these responses were unaltered in Olfr78-deficient mice. Accordingly, these authors concluded that Olfr78 is not required for CB response to hypoxia (Torres-Torrelo et al. 2018). Earlier studies reported that at very low values (e.g., <30 mmHg), CB sensory nerve activity either ceases to increase or may actually decrease (Fidone and Gonzalez 1986; Hornbein et al. 1961; Hornbein and Roos 1963), raising the question whether cellular responses to severe hypoxia are reflected in CB sensory nerve activity. This is an important issue because CB sensory nerve excitation is essential for triggering stimulation of breathing by the chemosensory reflex. We found severe hypoxia (Po2 ~10–15 mmHg) produced only a brief and weak CB sensory nerve excitation compared with Po2 of ~40 mmHg (Fig. 4 vs. Fig. 5), a finding consistent with earlier reports (Fidone and Gonzalez 1986; Hornbein et al. 1961; Hornbein and Roos 1963). Moreover, unlike stimulation of breathing elicited by 12% O2, severe hypoxia depressed breathing. It is uncertain whether changes in arterial blood Po2 reflects Po2 near glomus cells. Earlier measurements of CB tissue Po2 obtained by phosphorescence quenching probes yielded conflicting data (Kumar and Prabhakar 2012). Further studies are needed to resolve the relation between Po2 of arterial blood and Po2 levels near glomus cells. Nonetheless, based on measurements of CB sensory nerve activity, it appears that a Po2 of 40 mmHg and Po2 ~ 10–15 mmHg represent fundamentally different stimuli and that Olfr78 participates in CB responses to the former but not to a severe intensity of hypoxia.

What mechanisms might account for the reduced sensory nerve excitation by severe hypoxia? It may be that severe hypoxia compromised metabolism of glomus cell, resulting in decreased sensory nerve excitation. Alternatively, the robust [Ca2+]i elevation evoked by severe hypoxia might have released inhibitory neurochemical(s) from glomus cells, suppressing sensory nerve excitation. Assessing these possibilities requires detailed investigation, which is beyond the scope of the current study.

Chang et al. (2015) proposed that activation of Olfr78 by lactate is an essential step for CB sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia (Chang et al. 2015), a possibility that was questioned in a subsequent study (Torres-Torrelo et al. 2018). We found that lactate-evoked CB sensory nerve excitation and [Ca2+]i elevation were unaltered in Olfr78 null mice. Moreover, if lactate is the mediator of CB sensory nerve response to hypoxia, then exogenous lactate should evoke sensory nerve activation comparable to that evoked by hypoxia. However, 30 mM lactate (maximum concentration used in this study) produced modest stimulation of the CB sensory nerve activity compared with hypoxia (Po2 ~40 mmHg). Short-chain fatty acids such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate are also ligands for Olfr78 (Pluznick et al. 2013). An earlier study showed that acetate causes modest stimulation of the cat CB sensory nerve activity (Iturriaga 1996). Consistent with this study (Iturriaga 1996), we also found modest CB sensory nerve activation by acetate, as well as by propionate and butyrate, and these effects were indistinguishable between wild-type and Olfr78 null mice. Similarly to lactate, the magnitude of sensory nerve excitation by short-chain fatty acids was far less than that evoked by hypoxia. These results indicate that CB sensory nerve response to hypoxia is unlikely to be coupled to activation of Olfr78 either by lactate or by other short-chain fatty acids. The identity of endogenous ligand(s) evoking Olfr78-dependent CB sensory nerve excitation remains to be determined. Recent studies suggest that gaseous messenger H2S mediates CB sensory nerve excitation by hypoxia (Peng et al. 2010; Yuan et al. 2015). Whether H2S-dependent CB sensory nerve stimulation by hypoxia involves Olfr78 remains an intriguing possibility that requires detailed investigation.

In summary, the present study confirms the involvement Olfr78 in CB sensory nerve and glomus cell responses to the intensity of hypoxia, which stimulate breathing, but not severe hypoxia, which depress breathing. Furthermore, our data are not consistent with the notion that activation of Olfr78 either by lactate or by short-chain fatty acids participates in the CB response to hypoxia.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P01 HL-44454.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

N.R.P. conceived and designed research; Y.-J.P. and A.G. performed experiments; Y.-J.P., A.G., B.W., J.N., and A.P.F. analyzed data; Y.-J.P., J.N., A.P.F., and N.R.P. interpreted results of experiments; Y.-J.P. and A.G. prepared figures; Y.-J.P. and N.R.P. drafted manuscript; Y.-J.P., A.P.F., and N.R.P. edited and revised manuscript; Y.-J.P., A.G., B.W., J.N., A.P.F., and N.R.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Drs. J. Pluznick and A. Chang for providing Olfr78/Bl6 and Olfr78/JAX null mice, respectively. We are indebted to Dr. G. Kumar for valuable comments.

Preprint is available at https://doi.org/10.1101/757120.

REFERENCES

- Chang AJ, Kim NS, Hireed H, de Arce AD, Ortega FE, Riegler J, Madison DV, Krasnow MA. Chang et al. reply. Nature 561: E41, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0547-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AJ, Ortega FE, Riegler J, Madison DV, Krasnow MA. Oxygen regulation of breathing through an olfactory receptor activated by lactate. Nature 527: 240–244, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nature15721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauger S, Nsegbe E, Vardon G, Gaultier C, Gallego J. The effects of restraint on ventilatory responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia in adult mice. Respir Physiol 112: 215–225, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0034-5687(98)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejours P. Chemoreflexes in breathing. Physiol Rev 42: 335–358, 1962. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1962.42.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derecki NC, Cronk JC, Lu Z, Xu E, Abbott SB, Guyenet PG, Kipnis J. Wild-type microglia arrest pathology in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. Nature 484: 105–109, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature10907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidone SJ, Gonzalez C. Initiation and control of chemoreceptor activity in the carotid body. In: Handbook of Physiology, The Respiratory System, Control of Breathing, edited by Fishmann AP, Cherniack N, Widdicombe JG. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society, 1986, p. 247–312. [Google Scholar]

- Frappell P, Lanthier C, Baudinette RV, Mortola JP. Metabolism and ventilation in acute hypoxia: a comparative analysis in small mammalian species. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 262: R1040–R1046, 1992. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.6.R1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg SK, Lioy DT, Cheval H, McGann JC, Bissonnette JM, Murtha MJ, Foust KD, Kaspar BK, Bird A, Mandel G. Systemic delivery of MeCP2 rescues behavioral and cellular deficits in female mouse models of Rett syndrome. J Neurosci 33: 13612–13620, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1854-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbein TF, Griffo ZJ, Roos A. Quantitation of chemoreceptor activity: interrelation of hypoxia and hypercapnia. J Neurophysiol 24: 561–568, 1961. doi: 10.1152/jn.1961.24.6.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornbein TF, Roos A. Specificity of H ion concentration as a carotid chemoreceptor stimulus. J Appl Physiol (1985) 18: 580–584, 1963. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1963.18.3.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriaga R. Acetate enhances the chemosensory response to hypoxia in the cat carotid body in vitro in the absence of CO2-. Biol Res 29: 237–243, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DD, Yang T, Huang PL, Prabhakar NR. Altered respiratory responses to hypoxia in mutant mice deficient in neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J Physiol 511: 273–287, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.273bi.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar NN, Velic A, Soliz J, Shi Y, Li K, Wang S, Weaver JL, Sen J, Abbott SB, Lazarenko RM, Ludwig MG, Perez-Reyes E, Mohebbi N, Bettoni C, Gassmann M, Suply T, Seuwen K, Guyenet PG, Wagner CA, Bayliss DA. Regulation of breathing by CO2 requires the proton-activated receptor GPR4 in retrotrapezoid nucleus neurons. Science 348: 1255–1260, 2015. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Prabhakar NR. Peripheral chemoreceptors: function and plasticity of the carotid body. Compr Physiol 2: 141–219, 2012. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makarenko VV, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Fox AP, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Endogenous H2S is required for hypoxic sensing by carotid body glomus cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C916–C923, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00100.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maßberg D, Hatt H. Human olfactory receptors: novel cellular functions outside of the nose. Physiol Rev 98: 1739–1763, 2018. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Nanduri J, Raghuraman G, Souvannakitti D, Gadalla MM, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. H2S mediates O2 sensing in the carotid body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 10719–10724, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005866107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng YJ, Yuan G, Ramakrishnan D, Sharma SD, Bosch-Marce M, Kumar GK, Semenza GL, Prabhakar NR. Heterozygous HIF-1α deficiency impairs carotid body-mediated systemic responses and reactive oxygen species generation in mice exposed to intermittent hypoxia. J Physiol 577: 705–716, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluznick JL. Gut microbiota in renal physiology: focus on short-chain fatty acids and their receptors. Kidney Int 90: 1191–1198, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H, Peterlin Z, Sipos A, Han J, Brunet I, Wan LX, Rey F, Wang T, Firestein SJ, Yanagisawa M, Gordon JI, Eichmann A, Peti-Peterdi J, Caplan MJ. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived signals plays a role in renin secretion and blood pressure regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 4410–4415, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215927110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar NR. O2 sensing at the mammalian carotid body: why multiple O2 sensors and multiple transmitters? Exp Physiol 91: 17–23, 2006. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schild D, Restrepo D. Transduction mechanisms in vertebrate olfactory receptor cells. Physiol Rev 78: 429–466, 1998. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankersley CG, Fitzgerald RS, Kleeberger SR. Differential control of ventilation among inbred strains of mice. Am J Physiol Regu Integr Comp Physiol 267: R1371–R1377, 1994. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1994.267.5.R1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tankersley CG, Fitzgerald RS, Mitzner WA, Kleeberger SR. Hypercapnic ventilatory responses in mice differentially susceptible to acute ozone exposure. J Appl Physiol (1985) 75: 2613–2619, 1993. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1993.75.6.2613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres-Torrelo H, Ortega-Sáenz P, Macías D, Omura M, Zhou T, Matsunami H, Johnson RS, Mombaerts P, López-Barneo J. The role of Olfr78 in the breathing circuit of mice. Nature 561: E33–E40, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0545-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan G, Vasavda C, Peng YJ, Makarenko VV, Raghuraman G, Nanduri J, Gadalla MM, Semenza GL, Kumar GK, Snyder SH, Prabhakar NR. Protein kinase G-regulated production of H2S governs oxygen sensing. Sci Signal 8: ra37, 2015. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]