Abstract

Elevated potassium concentration ([K+]) is often used to alter excitability in neurons and networks by shifting the potassium equilibrium potential (EK) and, consequently, the resting membrane potential. We studied the effects of increased extracellular [K+] on the well-described pyloric circuit of the crab Cancer borealis. A 2.5-fold increase in extracellular [K+] (2.5×[K+]) depolarized pyloric dilator (PD) neurons and resulted in short-term loss of their normal bursting activity. This period of silence was followed within 5–10 min by the recovery of spiking and/or bursting activity during continued superfusion of 2.5×[K+] saline. In contrast, when PD neurons were pharmacologically isolated from pyloric presynaptic inputs, they exhibited no transient loss of spiking activity in 2.5×[K+], suggesting the presence of an acute inhibitory effect mediated by circuit interactions. Action potential threshold in PD neurons hyperpolarized during an hour-long exposure to 2.5×[K+] concurrent with the recovery of spiking and/or bursting activity. Thus the initial loss of activity appears to be mediated by synaptic interactions within the network, but the secondary adaptation depends on changes in the intrinsic excitability of the pacemaker neurons. The complex sequence of events in the responses of pyloric neurons to elevated [K+] demonstrates that electrophysiological recordings are necessary to determine both the transient and longer term effects of even modest alterations of K+ concentrations on neuronal activity.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Solutions with elevated extracellular potassium are commonly used as a depolarizing stimulus. We studied the effects of high potassium concentration ([K+]) on the pyloric circuit of the crab stomatogastric ganglion. A 2.5-fold increase in extracellular [K+] caused a transient loss of activity that was not due to depolarization block, followed by a rapid increase in excitability and recovery of spiking within minutes. This suggests that changing extracellular potassium can have complex and nonstationary effects on neuronal circuits.

Keywords: central pattern generator, depolarization block, F-I curves, spike threshold, stomatogastric nervous system

INTRODUCTION

Neuronal circuits must be robust to various environmental challenges. This is especially true for central pattern generators (CPGs) that produce essential motor patterns such as breathing, walking, and chewing (Marder and Calabrese 1996). Maintaining stability over a range of perturbations involves multiple intrinsic and synaptic mechanisms that operate over the course of minutes to days (Harris-Warrick 2010; Marder and Bucher 2001; von Euler 1983). Moreover, both theoretical and experimental evidence suggest that robust CPGs with similar activity patterns can have widely variable underlying cell intrinsic and synaptic conductances (Goaillard et al. 2009; Marder and Goaillard 2006; Norris et al. 2011; Prinz et al. 2004; Roffman et al. 2012; Schulz et al. 2006, 2007). Nevertheless, these individually variable circuits must maintain reliable outputs. How such circuits respond and adapt to environmental challenges remains an open question.

There are a number of global perturbations such as changes in temperature or pH that are likely to influence the behavior of most, if not all, neurons in a circuit. Previous work on the pyloric circuit of the crab stomatogastric ganglion (STG) has shown that the pyloric rhythm is remarkably resilient to substantial changes in temperature (Tang et al. 2010) or pH (Haley et al., 2018). Elevated extracellular potassium concentration ([K+]) is a physiologically relevant depolarizing stimulus associated with a wide array of conditions including thermal stress, epileptic seizures, kidney failure, traumatic brain injury, and stroke (Arnold et al. 2014; Baylor and Nicholls 1969; Chauvette et al. 2016; Jensen and Yaari 1997; Katayama et al. 1990; Krishnan and Kiernan 2009; Morrison et al. 2011; Pérez-Pinzón et al. 1995; Rodgers et al. 2007).

Experimentally, increased extracellular [K+] is often used to depolarize neurons and networks, with the usual aim of increasing neuronal and network activity (Ballerini et al. 1999; Lin et al. 2008; Panaitescu et al. 2009; Ruangkittisakul et al. 2011; Rybak et al. 2014; Sharma et al. 2015). In this study, we describe a series of short- and longer term effects of elevated [K+] on the pyloric circuit of the STG. In elevated [K+], we observe a short-term period (several minutes) in which rhythmic network activity is lost or slowed, followed by a period of adaptation in which rhythmic activity returns while still in elevated [K+]. These results demonstrate that the effects of high [K+] on neurons and networks can be complex and nonstationary.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Dissections

Adult male Jonah Crabs, Cancer borealis, (n = 90) were obtained from Commercial Lobster (Boston, MA) between December 2016 and December 2019 and maintained in artificial seawater at 10–12°C in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle. On average, animals were acclimated at this temperature for 1 wk before use. Prior to dissection, animals were placed on ice for at least 30 min. Dissections were performed as previously described (Gutierrez and Grashow 2009). In short, the stomach was dissected from the animal and the intact stomatogastric nervous system (STNS) was removed from the stomach, including the commissural ganglia, esophageal ganglion, and stomatogastric ganglion (STG) with connecting motor nerves. The STNS was pinned in a Sylgard-coated (Dow Corning) dish and continuously superfused with 11°C saline.

Solutions

Physiological (control) Cancer borealis saline was composed of 440 mM NaCl, 11 mM KCl, 26 mM MgCl2, 13 mM CaCl2, 11 mM Trizma base, and 5 mM maleic acid, pH 7.4–7.5 at 23°C (~7.7–7.8 pH at 11°C). High (1.5×, 2×, 2.5×, and 3×)-[K+] salines (16.5, 22, 27.5, and 33 mM KCl, respectively) were prepared by adding more KCl salt to the normal saline. Picrotoxin (PTX; 10−5 M) was used to block inhibitory glutamatergic synapses (Marder and Eisen 1984). Tetrodotoxin (TTX; 10−7 M) was used to block voltage-gated sodium channels for measurements of graded inhibition.

Electrophysiology

Intracellular recordings from STG somata were made in the desheathed STG with sharp glass microelectrodes (10–30 MΩ) filled with internal solution (10 mM MgCl2, 400 mM potassium gluconate, 10 mM HEPES buffer, 15 mM NaSO4, and 20 mM NaCl; Hooper et al. 2015). Intracellular signals were amplified with an Axoclamp 900A amplifier (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). Extracellular nerve recordings were made by building wells around nerves using a mixture of Vaseline and mineral oil and placing stainless steel pin electrodes within the wells to monitor spiking activity. Extracellular nerve recordings were amplified using model 3500 extracellular amplifiers (A-M Systems). Data were acquired using a Digidata 1440 digitizer (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA) and pClamp data acquisition software (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA; version 10.5). For identification of pyloric dilator (PD) and lateral pyloric (LP) neurons, somatic intracellular recordings were matched to action potentials on the pyloric dilator nerve (pdn), lateral pyloric nerve (lpn), and/or the lateral ventricular nerve (lvn).

Elevated [K+] Saline Application

Prior to applications of elevated [K+] saline, baseline activity was recorded for 30 min in control saline. Following the baseline recording, the STNS was superfused with elevated [K+] saline in concentrations ranging from 1.5× to 3×[K+] for 90 min. The preparation was then superfused with control saline for 30 min. Recordings from PD neurons in the isolated pacemaker kernel were made by superfusing the preparation with 10−5 M picrotoxin (PTX) saline until the inhibitory synaptic potentials in the PD neurons disappeared (20 min). These preparations were then exposed to 2.5×[K+] PTX saline for 90 min, followed by a 30-min wash in PTX saline.

Blocking Upstream Neuromodulatory Inputs

For the process of blocking descending modulatory inputs to the STG, a few holes in the sheath of the stomatogastric nerve (stn) were made longitudinally with a stainless steel minutien pin (0.1 mm). A Vaseline well was then built around the exposed portion of the stn. Propagation of axonal signaling, and thus neuromodulatory release, was blocked from upstream ganglia by replacing saline in the Vaseline well with 10−7 M TTX in a 750 mM sucrose solution. The preparation was then allowed to stabilize for 1 h before further perturbations.

Measuring Synaptic Strength Between LP and PD Neurons

We measured the strength of graded synaptic inhibition from the LP neuron onto PD neurons and from the PD neuron onto LP neurons in physiological saline with 10−7 M TTX and over time in 2.5×[K+] TTX saline. The synaptic currents were measured using two different protocols: voltage clamp and current clamp.

Voltage-clamp protocol.

The LP neuron and a PD neuron were both held in two-electrode voltage clamp. The synaptic current from the LP neuron to the PD neuron was measured as the current elicited in the postsynaptic neuron, held at either −90 mV or −10 mV, in response to depolarizing the presynaptic neuron to −10 mV for 1-s steps. The synaptic current was measured at the peak of the postsynaptic response. The reversal potential of the synaptic current was estimated by fitting a line to the peak postsynaptic currents at −90 mV and −10 mV. The synaptic current from the PD neuron to the LP neuron was measured as the current elicited in the postsynaptic neuron, held at −50 mV, in response to depolarizing the presynaptic neuron to −10 mV.

These measurements were repeated every 5 min for the entire experiment, which consisted of a 30-min baseline in 10−7 M TTX saline, followed by 60 min in 2.5×[K+] TTX, saline and, finally, a 30-min wash in TTX saline.

Current clamp protocol.

We used two-electrode current clamp to inject a series of ten 2-s current steps into the LP neuron from −50 mV up to −20 mV while simultaneously recording from a PD neuron held at −50 mV. Because of differences in input resistance, exact current steps varied between preparations. These current steps were repeated every 3 min for the entire experiment. We recorded the synaptic responses for 30 min in TTX saline. The preparation was then superfused with 2.5×[K+] TTX saline for 90 min, followed by a 30-min wash in TTX saline.

Threshold and Excitability Measurements

To measure the action potential threshold and excitability of PD neurons, two-electrode current clamp was used to apply slow ramps of current from −4 nA to +2 nA over 60 s. Resting membrane potential and input resistance were measured using short −1-nA current pulses during baseline recordings and after the application of elevated [K+] to ensure the integrity of the preparation (neurons with input resistance <4 MΩ were discarded). Three ramps were performed during baseline recordings at 10-min intervals, and ramps were performed in 2.5×[K+] at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90 min after the start of elevated [K+] superfusion. After the preparation was returned to control saline, three ramps were performed again at 10-min intervals. In recordings from the PD neurons with glutamatergic synapses blocked by PTX, baseline ramps were performed as described above, followed by three ramps in PTX saline. Preparations were then superfused with 2.5×[K+] PTX saline and washed in PTX saline following the same ramp procedure.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

Recordings were acquired using Clampex software (pClamp Suite by Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA; version 10.5) and visualized and analyzed using custom MATLAB analysis scripts. These scripts were used to detect and measure voltage-response amplitudes and membrane potentials, plot raw recordings and processed data, generate spectrograms, and perform some statistical analyses.

Spectral Analysis

Spectrograms were calculated using the Burg (1967) method for estimation of the power spectrum density in each time window. The Burg method (1967) fits the autoregressive (AR) model of a specified order p in the time series by minimizing the sum of squares of the residuals. The fast-Fourier transform (FFT) spectrum is estimated using the previously calculated AR coefficients. This method is characterized by higher resolution in the frequency domain than traditional FFT spectral analysis, especially for a relatively short time window (Buttkus 2000). We used the following parameters for the spectral estimation: data window of 3.2 s, 50% overlap to calculate the spectrogram, and number of estimated AR coefficients p = (window/4) + 1. Before the analysis, voltage traces were low-pass filtered at 5 Hz using a six-order Butterworth filter and downsampled. PD neuron burst frequency was calculated as the mean frequency at the peak spectral power in each sliding window.

Analysis of Interspike Interval Distributions

Intracellular voltage traces were thresholded to obtain spike times. Distributions of interspike intervals (ISIs) were calculated within 2-min bins. Hartigan’s dip test of unimodality (Hartigan and Hartigan 1985) was used to obtain the dip statistic for each of these distributions. This dip statistic was compared to Table 1 in Hartigan and Hartigan (1985) to find the probability of multimodality. The test creates a unimodal distribution function that has the smallest value deviations from the experimental distribution function. The largest of these deviations is the dip statistic. The dip statistic shows the probability of the experimental distribution function being bimodal. Larger value dips indicate that the empirical data are more likely to have multiple modes (Hartigan and Hartigan 1985).

Activity Pattern Plots

To determine the activity pattern of each PD neuron across the experiment, we analyzed the distribution of log-transformed ISIs in 2-min bins using Hartigan’s dip statistic. If the dip statistic was 0.05 or higher, the neuron was considered to be bursting. If the dip statistic was lower than 0.05, the neuron was considered to be tonically firing. Neurons with some spikes but not enough ISIs to calculate the dip were classified as sparsely firing. Neurons with no spikes in the observed window were classified as silent. We then plotted the activity patterns in these four categories (bursting, tonic, sparse firing, and silent) for each PD neuron across the entire experiment.

Identification of the Spike Threshold

The spike threshold was identified as the voltage point of the maximum curvature before the first spike. To find this, we calculated the first derivative of the voltage (dV/dt) and defined the spike onset as the point when dV/dt crosses the threshold value of 10 mV/ms.

All electrophysiology analysis scripts are available at the Marder laboratory GitHub (https://github.com/marderlab).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out using Excel 365 for ANOVA tests and MATLAB 2018a for all other analyses as described above.

RESULTS

Network Activity in the Pyloric Circuit

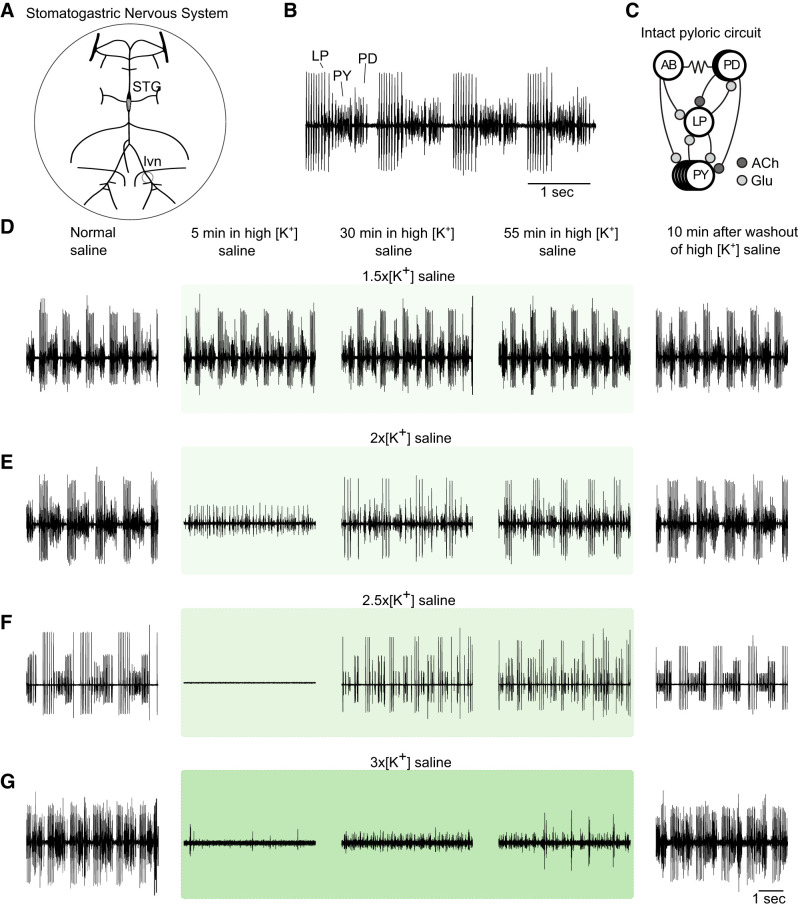

The STNS of the crab Cancer borealis was isolated intact from the stomach and pinned in a dish, allowing us to change the composition of the continuously flowing superfused saline (Fig. 1A). The STG contains identified neurons that drive the pyloric rhythm, which filters food through the animal’s foregut. Figure 1B shows a recording from the lateral ventricular nerve (lvn), which contains the axons of the LP, pyloric (PY), and PD neurons; the stereotypical triphasic pyloric pattern consists of repeated bursts of activity from the LP, PY, and PD neurons. Figure 1C illustrates the connectivity diagram of the pyloric network. The anterior burster (AB) neuron, the intrinsic oscillator that drives the circuit, is strongly electrically coupled to the two PD neurons, which burst synchronously with the AB neuron. Together, the AB and two PD neurons form the pacemaker kernel of the network, and their coordinated bursting initiates each triphasic cycle (Maynard 1972). Glutamatergic and cholinergic synaptic connections between neurons in the STG are all inhibitory and are both graded and spike mediated (Graubard et al. 1980; Manor et al. 1997). LP and PY neurons’ bursting activity, which results from postinhibitory rebound, compose the second and third phases of the pyloric rhythm, respectively, due to rhythmic inhibition from the pacemaker and reciprocal inhibition between LP and PY (Hartline and Gassie 1979; Selverston and Miller 1980).

Fig. 1.

The pyloric rhythm is disrupted by large changes in extracellular potassium concentration ([K+]). A: diagram of the dissected stomatogastric nervous system (STNS) showing the stomatogastric ganglion (STG) and motor nerves (lvn). The entire STNS was superfused with saline with altered [K+]. B: the triphasic pyloric rhythm is illustrated in an extracellular recording from the lvn, which contains axons from lateral pyloric (LP), pyloric (PY), and pyloric dilator (PD) neurons. C: connectivity diagram of the pyloric circuit of the crab Cancer borealis. All chemical synapses are inhibitory. Resistor symbols denote electrical synapses. D–G: recordings of lvn spiking activity during application of elevated [K+] saline (green boxes) with concentrations 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, and 3.0 times the physiological extracellular concentration of potassium (1.5×, 2×, 2.5×, and 3×[K+], respectively).

The Pyloric Rhythm Is Temporarily Disrupted by High Extracellular Potassium

To test the response of the pyloric rhythm to changes in extracellular [K+], we superfused saline with elevated [K+] over the STNS while continuously recording the activity of pyloric neurons extracellularly from the lvn. We tested concentrations of [K+] that were 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3 times the physiological concentrations to study the dose-dependent responses of pyloric neurons to changes in extracellular [K+]. When extracellular [K+] was increased to 1.5× the physiological concentration (Fig. 1D; n = 4), the pyloric rhythm remained triphasic and was negligibly affected. When exposed to 2×[K+] (Fig. 1E; n = 20), the response of pyloric neurons was more variable. In some cases (n = 9 of 20) there was a short disruption of the triphasic pyloric rhythm, which was followed by the recovery of spiking activity in all preparations.

Higher concentrations of extracellular [K+] produced more pronounced effects on pyloric activity: 2.5×[K+] (Fig. 1F; n = 12 extracellular-only recordings) reliably and profoundly altered the pyloric rhythm. During the application of 2.5×[K+] saline, all preparations exhibited a disruption of action potentials from pyloric neurons, followed by recovery of spiking activity during continued exposure to 2.5×[K+] saline. Application of 3×[K+] saline to the STNS resulted in consistent loss of the pyloric rhythm (Fig. 1G; n = 5). Nonetheless, at 3×[K+], few of the preparations recovered sustained activity. Based on these responses, we settled on 2.5×[K+] for further study, as it reliably disrupted the pyloric rhythm and was accompanied by a sustained recovery of spiking or bursting activity during the continued application of 2.5×[K+] saline.

The pattern of loss and recovery of pyloric activity in 2.5×[K+] saline was consistent across all experiments. To obtain more detailed information on the effects of increased [K+], we recorded intracellularly from pyloric neurons while superfusing 2.5×[K+] saline.

PD and LP Neurons Depolarize and Temporarily Lose Spiking Activity in High Extracellular Potassium

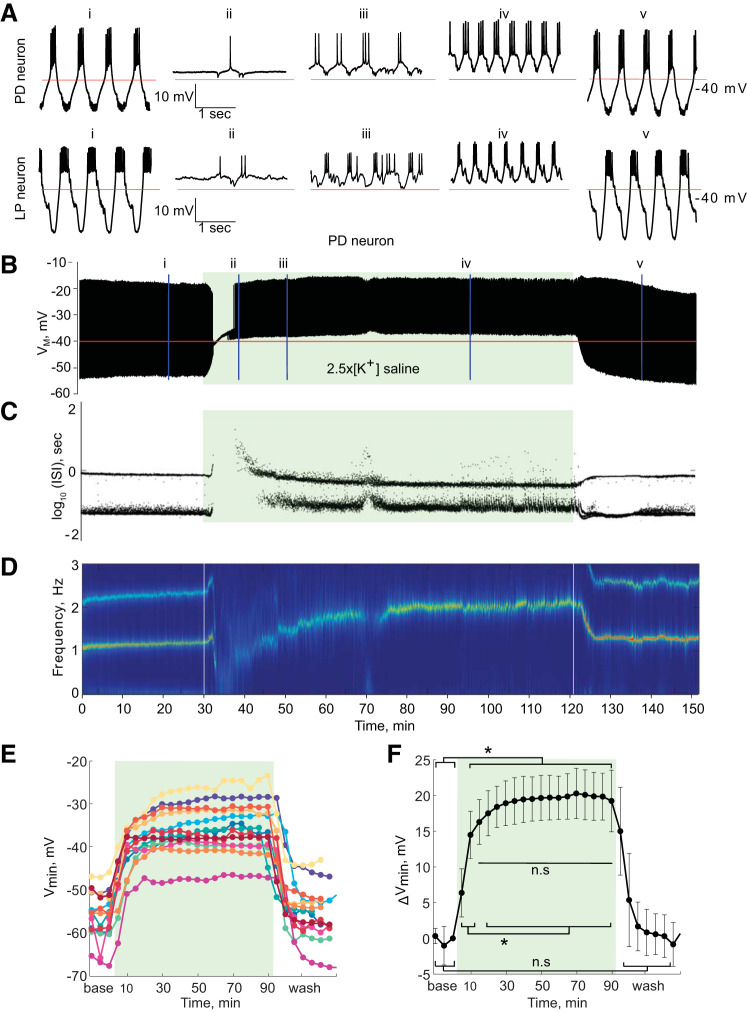

Intracellular recordings showed a marked loss of spiking activity from pyloric neurons (crash) in response to the application of 2.5×[K+] saline, in agreement with the previously described extracellular recordings. In the representative example shown in Fig. 2, the PD and LP neurons fired bursts robustly in normal physiological saline (Fig. 2Ai). Within a few minutes of the start of 2.5×[K+] saline application, the minimum membrane potentials of the PD and LP neurons depolarized by 15 and 22 mV, respectively (Fig. 2Aii), coincident with a reduction in firing frequency. Subsequently, the activity of both the LP and PD neurons became more burstlike over the course of the 90-min application of 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 2A, iii and iv) and recovered to normal baseline behavior when returned to physiological saline (Fig. 2Av).

Fig. 2.

Pyloric dilator (PD) and lateral pyloric (LP) neurons in saline with 2.5 times the physiological extracellular concentration of potassium (2.5×[K+] saline). Green-shaded boxes indicate the period of 2.5×[K+] saline superfusion. A: 3-s segments of PD and LP activity are shown in physiological saline (i), 10 (ii), 20 (iii), and 70 min (iv) into application of 2.5×[K+] saline, and upon return to physiological saline (v). B: voltage trace of a PD neuron’s activity for the entire representative experiment. C: interspike intervals (ISI) of the PD neuron’s activity over the course of 2.5×[K+] saline application plotted on a log scale. D: spectrogram of the PD neuron’s voltage trace. Color code represents the amplitude density, with red representing the maximum amplitude density and blue the minimum amplitude density. Low-frequency band with the strongest power corresponds to the fundamental frequency of the periodic signal; secondary band at higher frequency corresponds to its 2f harmonic. E: mean minimum membrane potential (Vmin) for each PD neuron in 5-min bins. F: average change in PD neurons’ minimum membrane potential (ΔVmin) compared with baseline in 5-min bins. Error bars are SD. *P < 0.05, minimum membrane potential depolarized significantly when 2.5×[K+] saline was applied (one-way repeated measures ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test, all P < 0.05) but did not change significantly between 10 and 90 min in 2.5×[K+] (n.s., no significant difference; all P > 0.05). The PD minimum membrane potential returned to baseline levels in wash (n.s., baseline compared with wash, all P > 0.05). VM, membrane potential.

The full pattern of depolarization and recovery of spiking can be seen by plotting time-condensed voltage traces for the PD neuron (the response of the LP neuron closely resembles that of the PD neuron) for the entire 150-min experiment. In this trace, the membrane potential initially depolarized in 2.5×[K+] saline and was followed by a loss of spiking activity (Fig. 2B). To visualize spiking behavior over the course of the experiment, we plotted the instantaneous interspike intervals (ISIs) of the PD neuron for the whole experiment on a log scale [log10(ISI); Fig. 2C]. All healthy PD neurons in control saline displayed regular bursting activity that yielded a bimodal distribution of ISIs, reflecting the relatively longer ISI period between bursts and the shorter ISIs of spikes within a burst (Fig. 2C). Over the course of the 2.5×[K+] saline application, both the PD and LP neurons recovered rhythmic bursts of action potentials, which is clear from the reemergence of two ISI bands (Fig. 2C).

Bursting activity is suggestive of the re-appearance of slow membrane potential oscillations. These slow oscillations are well visualized in spectrograms of the neuron’s membrane potential. Recovery of bursting activity in elevated [K+] saline can be seen as the reappearance of a strong frequency band at 1–2 Hz in the voltage spectrogram (Fig. 2D).

We calculated the most hyperpolarized point of the membrane potential in each burst averaged over 5-min bins for all PD neurons to study the depolarizing effect of 2.5×[K+] saline over time. PD neurons depolarized upon application of 2.5×[K+] saline and remained depolarized for the duration of the application (Fig. 2E). Figure 2F shows pooled data from these experiments: PD neurons depolarized upon application of 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 2F; one-way repeated measures ANOVA, F26,312 = 152.43, Tukey post hoc test, all P < 0.05; average depolarization after 10 min, 14.5 ± 3.3 mV) After the initial change in the first 10 min in 2.5×[K+], the minimum membrane potential did not change for the remainder of the elevated [K+] application (no significant differences for all comparisons 15 min–90 min 2.5×[K+]). The minimum membrane potential returned to baseline levels when the preparations were returned to physiological saline (no significant differences between all baseline and wash time points). The behavior of LP neurons in 2.5×[K+] was very similar to that of PD neurons; LP neurons depolarized by 16.5 ± 2.9 mV after 10 min in 2.5×[K+] (n = 5) and remained depolarized for the duration of the elevated [K+] application.

Although pyloric activity and circuit connectivity are highly conserved across animals, responses of individual PD neurons to 2.5×[K+] saline varied substantially across animals. Application of 2.5×[K+] saline led to a period of silence in 9 of 13 PD neurons, with a large variability in the duration of silence and extent of recovery across animals (n = 13). The duration of silence of the PD neurons elicited by 2.5×[K+] saline application varied from 1 to 62 min (10.9 ± 5.8 min, mean ± SD).

We were interested to see whether aspects of baseline activity of each PD neuron influenced the neuron’s time to recovery. Therefore, for each PD neuron, we calculated the mean minimum membrane potential during baseline recordings, the change in membrane potential upon application of 2.5×[K+] saline, and the baseline bursting frequency. We found no correlation between any of these values and silence duration for a given PD neuron in 2.5×[K+] saline (R2 = 0.203, R2 = 0.104, and R2 = 0.012, respectively).

PD Neurons in the Isolated Pacemaker Kernel Continue Spiking in 2.5×[K+] Saline

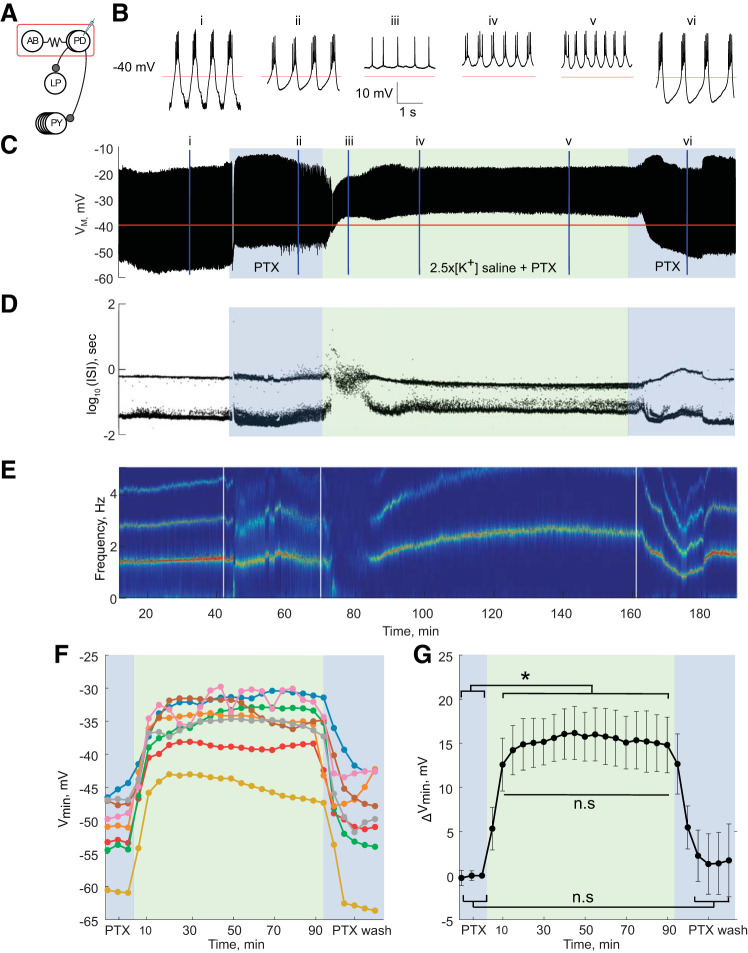

From the previous experiments, it was unclear to what extent the crash and recovery of activity in 2.5×[K+] saline was impacted by presynaptic inputs to the PD neurons. The only feedback from the rest of the pyloric circuit to the pacemaker ensemble is the glutamatergic inhibitory input from the LP neuron (Eisen and Marder 1982). Thus the pacemaker kernel can be studied in isolation from the other pyloric neurons by superfusing saline with 10−5M picrotoxin (PTX), which blocks ionotropic glutamatergic synapses in the STG (Fig. 3A) (Bidaut 1980).

Fig. 3.

Pyloric dilator (PD) neuron isolated from its presynaptic glutamatergic synapses with picrotoxin (PTX). A: connectivity diagram of the pyloric network with picrotoxin (PTX) blocking glutamatergic signaling and only cholinergic synapses still present. AB, anterior burster neuron; LP, lateral pyloric neuron; PY, pyloric neuron. B: 3-s segments of the PD neuron’s activity in physiological saline (i), 20 min into application of 10−5M PTX saline (ii), at 10 (iii), 20 (iv), and 70 min (v) into application of PTX saline with 2.5 times the physiological extracellular concentration of potassium (2.5×[K+] saline + PTX), and upon return to physiological saline (vi). C: voltage trace of the PD neuron over the entire experiment. Blue-shaded boxes indicate time of 10−5M PTX saline superfusion, and green-shaded box indicates the 90-min period of 2.5×[K+] saline + PTX superfusion. Color scheme is maintained in D, F, and G. D: interspike intervals (ISIs) from the PD neuron over the course of the experiment plotted on a log scale. E: spectrogram of PD neuron’s voltage trace. Color code reflects the amplitude density, with red representing the maximum amplitude density and blue the minimum amplitude density. F: mean minimum membrane potential (Vmin) of each PTX PD neuron in 5-min bins. G: average change in PTX PD neurons’ minimum membrane potential (ΔVmin) compared with baseline in 5-min bins. Error bars are SD. *P < 0.05, minimum membrane potential depolarized significantly when 2.5×[K+] saline + PTX was applied (one-way repeated measures ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test, all P < 0.05) but did not change significantly after 10 min in 2.5×[K+] saline + PTX for the duration of the elevated [K+] application (n.s., no significant difference; all P > 0.05). The minimum membrane potential returned to baseline levels in wash (n.s., baseline compared with wash, all P > 0.05).

The response of PD neurons to 2.5×[K+] saline in the presence of PTX was markedly different from the behavior of PD neurons in the absence of PTX. Figure 3 illustrates a representative example of the activity of a PD neuron in 2.5×[K+] PTX saline. The neuron initially switched from rhythmic bursting to tonic spiking activity in 2.5×[K+] PTX saline (Fig. 3Biii), followed by recovery of bursting activity that became more pronounced with time (Fig. 3B, iv, v, and vi). There was no interruption of spiking activity in PD neurons upon the superfusion of 2.5×[K+] PTX saline (Fig. 3C) compared with 2.5×[K+] alone (compare with Fig. 2B). The recovery of bursting activity in 2.5×[K+] PTX saline can also be seen in the emergence of two distinct ISI bands (Fig. 3D) and the emergence of a clear frequency band in the spectrogram of the PD intracellular voltage trace (Fig. 3E).

We further quantified the responses of PD neurons to 2.5×[K+] PTX saline by calculating the mean minimum membrane potential in 5-min bins for each neuron across the experiment (n = 8; Fig. 3F). Similar to PD neurons in the intact circuitry, all PD neurons in PTX depolarized in 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 3G; one-way repeated measures ANOVA, F26,182 = 82.40, Tukey post hoc test, all P < 0.05; mean depolarization after 10 min, 12.6 ± 3.0 mV). The minimum membrane potential of PD neurons in PTX then remained stable until the end of the application of 2.5×[K+] and hyperpolarized back to baseline levels when returned to physiological [K+] saline (Fig. 3G; no significant differences between all baseline and wash time points).

Synaptic Inputs Alter Response of PD Neurons to 2.5×[K+] Saline

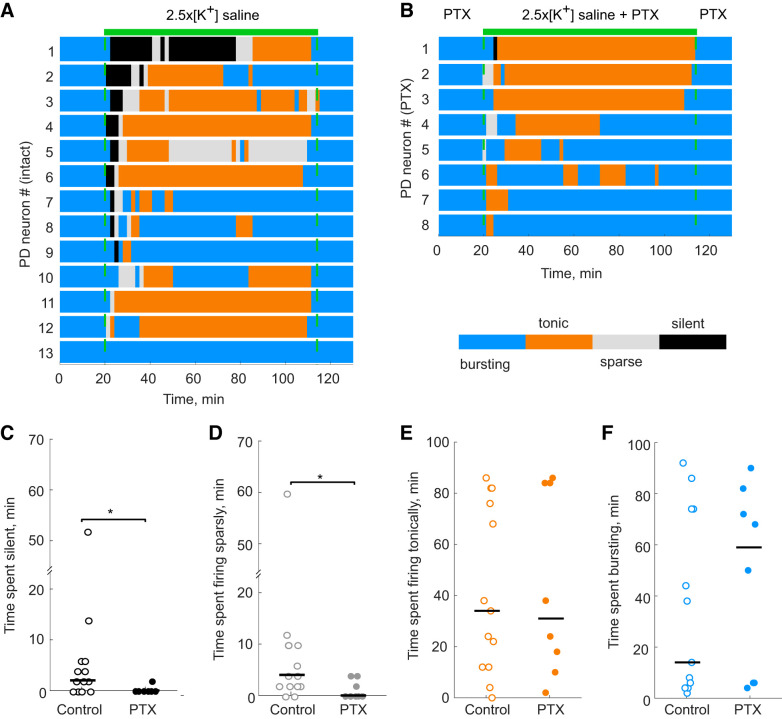

The activity of PD neurons upon initial 2.5×[K+] saline application differed in the presence or absence of PTX, which indicates existence of a circuit-driven response to elevated [K+] saline. To quantify this effect, we used values from the Hartigan’s dip test calculated from 2-min-bin log(ISI) distributions to determine the time that each PD neuron was either bursting, tonically firing, sparsely spiking, or silent throughout the experiment and plotted the assigned category for each PD neuron over time (see materials and methods).

In the intact circuit, the majority (n = 9 of 13) of PD neurons exhibited a period of silence of at least 2 min following the application of 2.5×[K+] saline and then recovered spiking activity over a variable amount of time (Fig. 4A). In 2.5×[K+] PTX saline, PD neurons either remained active or only briefly went silent, and then demonstrated robust recovery of spiking or bursting activity (Fig. 4B). The average time of PD silence in 2.5×[K+] saline was significantly less with the addition of PTX (Fig. 4C; Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.041), as was the average time of PD sparse firing between PTX and control PD neurons (Fig. 4D; Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.047). In both the duration of silence and sparse firing states, there was one PD neuron that spent substantially more time in either of these states; however, removing this point did not affect the statistical differences between the control and PTX groups. Neither the differences in average time of tonic firing (Fig. 4E; Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.94) nor the differences in average time of bursting activity were statistically significant in the presence or absence of PTX (Fig. 4F; Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.76).

Fig. 4.

Pyloric dilator (PD) neurons respond differently to saline with 2.5 times the physiological extracellular concentration of potassium (2.5×[K+] saline) in the presence (PTX) and absence (control) of picrotoxin. A: activity patterns (defined in materials and methods and denoted by color blocks) of control PD neurons exposed to 2.5×[K+] saline. Each line represents the activity of a single PD neuron. B: activity patterns of PTX PD neurons exposed to 2.5×[K+] saline + PTX. C: control PD neurons exhibit longer periods of silence (black) upon 2.5×[K+] saline application compared with PD neurons in PTX (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, *P = 0.0129). D: control PD neurons exhibit longer periods of sparse firing (gray) upon 2.5×[K+] saline application compared with PD neurons in PTX (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, *P = 0.034). E and F: control PD neurons do not show significant differences in the amount of time in tonic firing (E; orange; n.s., no significant difference, P = 0.77) or in burst firing (F; blue) modes upon 2.5×[K+] saline application compared with PD neurons in PTX (n.s., P = 0.51).

Overall, these data suggest that the initial silence of PD neurons in 2.5×[K+] is largely due to increased local synaptic inhibition.

Loss of Neuromodulatory Input Does Not Substantially Affect the Response of PD Neurons to 2.5×[K+] Saline

The STG receives neuromodulatory input from neurons in three presynaptic ganglia [2 commissural ganglia (CoG) and 1 esophageal ganglion (OG)], which were dissected out intact and also exposed to changes in extracellular potassium concentrations (Fig. 1A). Neuromodulation adds a layer of complexity to almost any study of neural circuits, as modulators can change network properties such as synaptic strength or cellular excitability through changes in voltage-dependent conductances. Neuromodulators also impact circuit responses to global perturbations such as increases in temperature in complicated ways, as some modulators can increase robustness of responses to a particular perturbation, while others increase the sensitivity of the system to the same perturbation (Haddad and Marder 2018). Thus, to investigate the impact of descending neuromodulatory inputs on the response of pyloric neurons to elevated [K+], we blocked neurotransmission in the stomatogastric nerve (stn) containing the axons of modulatory neurons with a solution of sucrose and tetrodotoxin (TTX) before applying 2.5×[K+] saline.

Upon blocking of neuromodulatory input, PD neurons depolarized slightly (3–4 mV) and the pyloric frequency slowed. After 1 h, we applied 2.5×[K+] saline for 90 min (n = 9). Similar to control preparations, in STGs with neuromodulatory input blocked, PD neurons depolarized 10–20 mV over the course of a few minutes, ceased all activity for a period of time (n = 8 of 9 PD neurons became silent for at least 2 min), and all PD neurons recovered spiking activity over a variable amount of time (time of silence, 9.2 ± 6.3 min). Overall, the total time PD neurons spent bursting, tonically firing, sparsely firing, or silent in 2.5×[K+] saline was not significantly different between control preparations and those with neuromodulatory input blocked (Kruskal–Wallis test, P = 0.55, 0.32, 0.56, and 0.32, respectively). Therefore, the effects of neuromodulation cannot fully explain the adaptation and recovery of spiking activity of PD neurons in 2.5×[K+] saline.

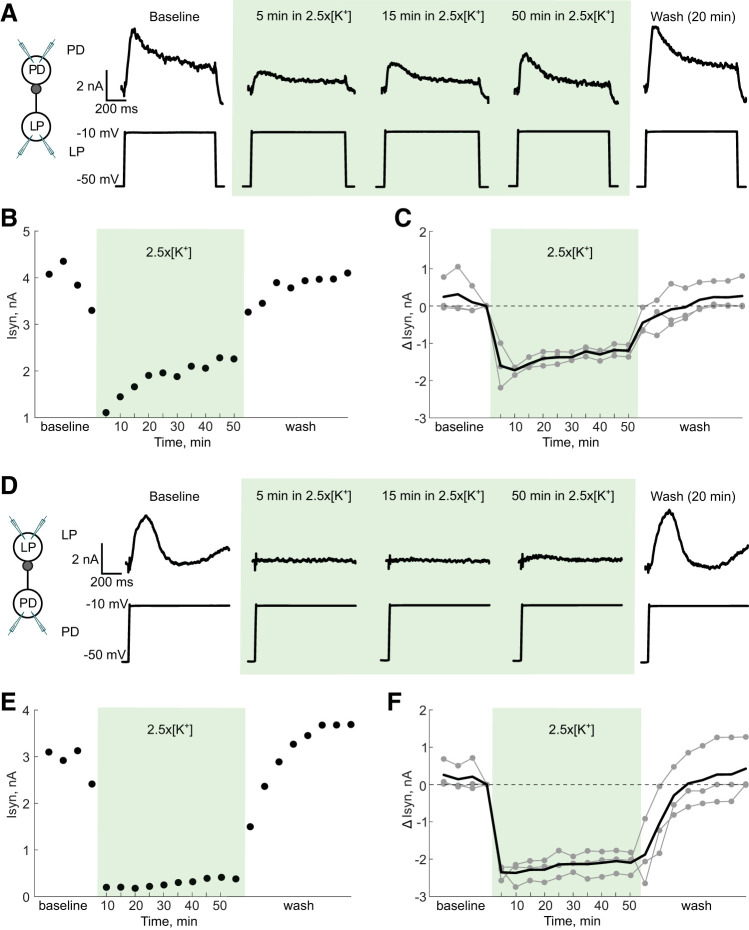

Graded Synaptic Currents Between the LP and PD Neurons Do Not Change Substantially over Time in 2.5×[K+]

STG neurons release neurotransmitter as a graded function of presynaptic membrane potential (Graubard 1978; Manor et al. 1997), with a release threshold close to the trough of the slow wave seen during normal activity. PD neurons temporarily lose and then regain spiking activity in 2.5×[K+]. One possible explanation for these results is that graded presynaptic inhibition from the LP neuron, which also temporarily loses activity, onto the PD neuron decreases over time in 2.5×[K+] saline, allowing spiking activity to reappear. We were interested specifically in the role of graded inhibition, because the recovery of spiking activity in PD neurons typically occurs while the rest of the pyloric network is silent.

To test this, we measured the strength of the LP-to-PD and PD-to-LP synapses over time in TTX control saline and in 2.5×[K+] TTX saline. We measured the synaptic amplitudes in two ways, first using two-electrode current clamp (n = 3) and then using two-electrode voltage clamp (n = 3). Both techniques consistently showed that there is no decrease in graded synaptic transmission during adaptation to high extracellular [K+]. Figure 5 summarizes the results of the voltage-clamp experiments. In 2.5×[K+] TTX saline there was a large decrease in the graded synaptic current from LP to PD measured at −10 mV (Fig. 5A). This decrease in synaptic current can be accounted for by the increase in extracellular [K+] leading to a depolarization of the synaptic reversal potential. The magnitude of the synaptic current in 2.5×[K+] saline did not decrease over time, and in the example shown, slightly increased (Fig. 5B), indicating that the recovery is not likely a result of transmitter depletion. In all six experiments, there was no decrease in the LP-to-PD synapse strength over time in 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 5C; voltage clamp).

Fig. 5.

Graded synaptic currents between lateral pyloric (LP) and pyloric dilator (PD) neurons do not change substantially over time in 2.5 times the physiological extracellular concentration of potassium (2.5×[K+]). Two-electrode voltage clamp was used in both the LP and PD neurons to bring the PD neuron’s membrane potential to either −90 mV or −10 mV for 3 s while stepping the LP neuron from −50 mV to −10 mV for 1 s. A–C show the synaptic currents from the LP neuron to the PD neuron, with the PD neuron at −10 mV and the LP neuron depolarized to −10 mV. A: representative traces of the synaptic current (Isyn) in a PD neuron in response to the LP neuron’s depolarization over time in high [K+] and wash. B: maximum PD synaptic current over the course of the entire experiment. C: change in synaptic current (ΔIsyn) relative to the last point measured in baseline. Individual experiments are shown in gray; the mean change in current is represented by the black line. D–F show the synaptic currents from the PD neuron to the LP neuron, with the LP neuron held at −50 mV and the PD neuron depolarized to −10 mV. D: representative traces of the synaptic current in the LP neuron in response to the PD neuron’s depolarization over time in high [K+] and wash. E: maximum LP synaptic current over the course of the entire experiment. F: change in synaptic current elicited in the LP neuron relative to the last point measured in baseline. Individual experiments are shown in gray; the mean change in current is represented by the black line.

In voltage clamp, we also measured the strength of graded synaptic transmission from the PD neuron to the LP neuron (Fig. 5D). The magnitude of the synaptic current also decreased markedly upon application of 2.5×[K+] saline (again because the reversal potential depolarized) and remained low throughout the application (Fig. 5E). This effect was consistent across all preparations (Fig. 5F). Thus decreased graded inhibition cannot account for the recovery of spiking activity in pyloric neurons over time in elevated [K+] saline.

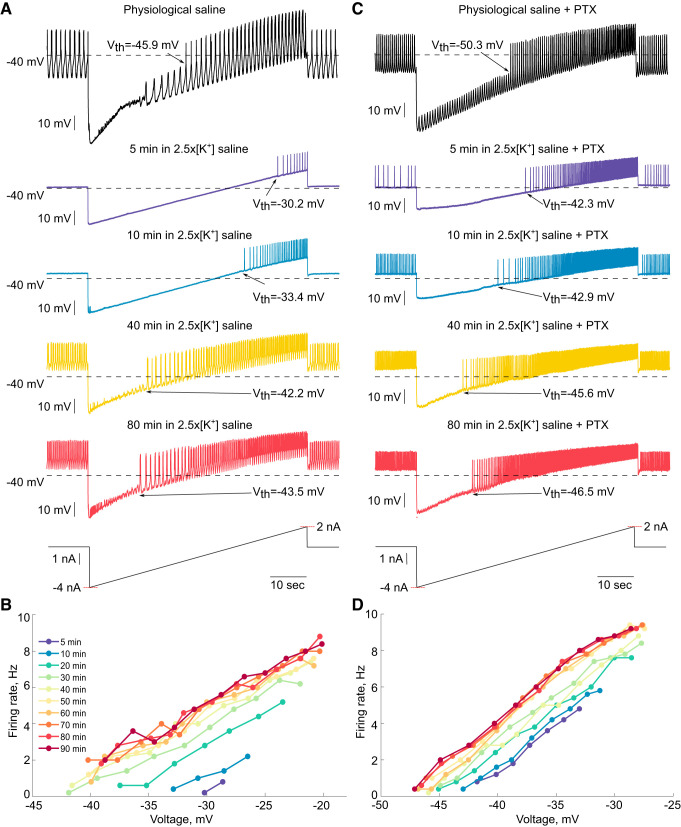

Intrinsic Excitability of PD Neurons Changes Rapidly during Exposure to 2.5×[K+] Saline

Loss of activity in response to a depolarizing stimulus could be due to depolarization block, a condition in which action potentials cannot occur because sustained depolarization causes a large proportion of voltage-gated sodium channels to remain inactivated. Thus a neuron in depolarization block cannot be induced to fire action potentials by further depolarization. To test whether periods of silence in high K+ were due to depolarization block, we applied 60-s steady ramps of current from −4 nA to +2 nA to PD neurons at several time points during the period of silence elicited by application of 2.5×[K+] saline. In silent PD neurons, action potentials could always be induced by injecting positive current, indicating that this period of silence is not due to depolarization block (Fig. 6A, ramps at 5 and 10 min).

Fig. 6.

Excitability of pyloric dilator (PD) neurons during exposure to saline with 2.5 times the physiological extracellular concentration of potassium (2.5×[K+] saline). A: two-electrode current clamp was used to inject current ramps from −4 nA to +2 nA over 60 s. Representative activity is shown during ramps from a PD neuron in 2.5×[K+] at 5, 10, 40, and 80 min after the onset of 2.5×[K+] saline application. B: average firing rates calculated in 5-s bins for each ramp in 2.5×[K+] saline from the neuron shown in A plotted against the average membrane potential of the corresponding bin. C: representative activity during ramps for a picrotoxin (PTX)-exposed PD neuron at 5, 10, 40 and 80 min after the onset of 2.5×[K+] saline + PTX application. D: average firing rates calculated in 5-s bins for each ramp in 2.5×[K+] saline from the neuron shown in C are plotted against the average membrane potential in the corresponding bin. Vth, spike threshold.

To determine the excitability of PD neurons during application of 2.5×[K+], we repeated the slow current ramps from −4 nA to +2 nA at 5, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, and 90 min after the beginning of the 2.5×[K+] saline application in the presence or absence of PTX. In the representative example shown in Fig. 6A, there was a clear change in the spike threshold and frequency of spikes elicited in the PD neuron by the current ramp as a function of time in 2.5×[K+] saline. As more time in 2.5×[K+] elapsed, more spikes were elicited at the same membrane potentials during the current ramp (Fig. 6B).

Similar to PD neurons in the intact circuitry, PD neurons in the presence of PTX also become more excitable over time in 2.5×[K+] saline. In the representative example shown in Fig. 6C, although the PD neuron remained tonically active throughout the application of 2.5×[K+] saline, there was a shift in both the spike threshold and spike frequency during the ramps over time in 2.5×[K+]. Similar to the PD neuron in the intact circuitry (Fig. 6B), the firing rate of the PD neuron in PTX increased over time in 2.5×[K+] at all membrane potentials during the ramps (Fig. 6D).

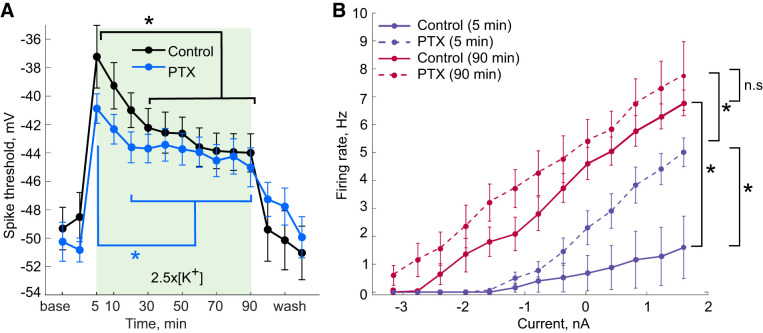

Figure 7 summarizes the changes in spike threshold and firing rate of PD neurons across all preparations as a function of time in 2.5×[K+] saline. In both control and PTX conditions, PD neuron spike threshold hyperpolarized over time in 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 7A). For most of these neurons the greatest changes in firing rate and spike threshold occurred during the first 10 min of the 2.5×[K+] saline application, which is similar to the time in which most PD neurons recover spiking activity in elevated [K+]. Control PD neurons had significantly different spike thresholds between the 5-min and the 30- through 90-min time points in 2.5×[K+] saline and also between the 10-min and the 70- through 90-min time points in 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 7A; one-way repeated measures ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test, F14,56 = 19.99, all P < 0.05). Across all PTX PD neurons there was a significant change in spike threshold between the 5-min and 20- through 90-min time points in 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 7A; one-way repeated measures ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test, F14,98 = 30.98, all P > 0.05).

Fig. 7.

Excitability of pyloric dilator (PD) neurons in presence (PTX) and absence (control) of picrotoxin in saline with 2.5 times the physiological extracellular concentration of potassium (2.5×[K+] saline). A: spike thresholds (mean ± SE) for control and PTX PD neurons, calculated from 60-s ramps from −4 nA to +2 nA. Error bars are SE. *P < 0.05, one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Tukey post hoc test; all comparisons between brackets). B: average frequency-current (F-I) curves for control PD neurons (solid lines) and PD neurons in PTX (dashed lines) in the beginning of 2.5×[K+] saline application (5 min; blue lines) and at the end of 2.5×[K+] saline application (90 min; red lines). *P = 0.001, significant difference in the F-I curves of PTX and control PD neurons after 5 min in 2.5×[K+] saline (two-way repeated measures ANOVA). Both control and PTX PD neurons became more excitable between the early (5 min) and late (90 min) time points in 2.5×[K+] (two-way repeated measures ANOVA, *P = 0.009 and *P = 0.006, respectively).

To visualize changes in PD neuron excitability and how this depends on both synaptic inputs and time in 2.5×[K+] saline, we calculated average frequency-current (F-I) curves for all PD neurons at the beginning (5-min ramp) and at the end (90-min ramp) of the 2.5×[K+] saline application. Early in the application of 2.5×[K+], at the 5-min time point, PTX PD neurons showed higher firing rates than control PD neurons (Fig. 7B, purple lines; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, F1,11 = 18.52, P = 0.001). This difference represents the initial effect of local inhibitory connections on neuronal excitability and is consistent with the fact that PTX neurons remain active upon application of 2.5×[K+], whereas control PD neurons typically lose spiking activity. There was a shift in the average F-I curve between the early (5 min) and late (90 min) time points in 2.5×[K+] saline (Fig. 7B, solid lines; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, F1,4 = 23.04, P = 0.009), indicating an increase in excitability. This was also seen for PTX PD neurons in 2.5×[K+]. There was a statistically significant difference between the early (5 min) and late (90 min) PTX PD neuron F-I curves (Fig. 7B, dashed lines; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, F1,7 = 15.22, P = 0.006). Finally, by the end of the 2.5×[K+] application (90 min), there was no significant difference between the F-I curves of PTX and control PD neurons (Fig. 7B, red lines; two-way repeated measures ANOVA, F1,11 = 1.42, P = 0.258).

DISCUSSION

External solutions containing high extracellular [K+] are commonly used to depolarize neurons and other tissues, often with the assumption that depolarization will be associated with an increase in neuronal activity. Some treatments with high extracellular [K+] are done transiently, for short periods of time, whereas in other experiments, preparations are kept in high extracellular [K+] for many hours. In this article we demonstrate adaptations to high [K+] that occur in minutes to hours, which could complicate the interpretation of some experiments that use elevated [K+]. Moreover, the phenomena described here may also have implications for disease states in which high extracellular K+ concentrations are abruptly elevated for minutes, hours, or days.

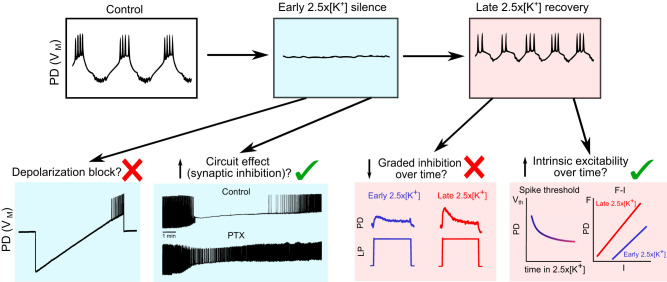

Figure 8 summarizes the core data and conclusions of this article and illustrates the evolution of the changes in normal and high [K+]. Most importantly, this schematic shows that the effects of high [K+] are not stationary and instead have an initial set of effects followed by an adaptation phase. This result suggests that researchers using other preparations should be alert to the possibilities of different short- and long-term effects of changing extracellular ion concentrations.

Fig. 8.

Schematic of possible mechanisms explaining the response to elevated potassium concentration ([K+]). Top row: boxes illustrate typical behavior of a pyloric dilator (PD) neuron in control saline, early 2.5×[K+] saline (blue), and late 2.5×[K+] (pink). The initial loss of spiking activity in early 2.5×[K+] saline could potentially be explained by depolarization block or by circuit-mediated inhibition. Action potentials can be elicited in silent PD neurons by injecting positive current (red X), showing that this silence is not due to depolarization block (trace from Fig. 6; bottom row, left blue box). PD neurons in early 2.5×[K+] saline do not lose spiking activity when inhibitory glutamatergic input is blocked (green checkmark), indicating that the initial silence can be explained by local inhibition from the LP neuron (traces from Figs. 2 and 3; bottom row, right blue box). The second phenomenon is the recovery of spiking and bursting activity late in 2.5×[K+] saline application. This recovery of spiking could be due to a reduction in graded inhibition over time and/or an increase in intrinsic excitability. Upon application of 2.5×[K+] saline, the response of PD neurons to lateral pyloric neuron (LP) depolarization is greatly reduced, and slightly increases as time increases in 2.5×[K+] saline (red X), indicating that a change in synaptic inhibition is unlikely to be responsible for the recovery of spiking activity (traces from Fig. 5; bottom row, left red box). Measurements of spike threshold and firing rate frequency-current (F-I) curves from PD neurons late and early in 2.5×[K+] saline show that the intrinsic excitability of PD neurons increases over time (green checkmark; data from Fig. 7; bottom row, right red box). This shift in excitability could be responsible for the recovery of spiking and rhythmic activity over time.

Inhibitory Effect of a Depolarizing Stimulus

It is generally assumed that positive current or depolarization of a neuron’s membrane potential will lead to an increase in neuronal activity and that extreme depolarizations can lead to loss of activity through depolarization block. However, we present a case in which depolarization due to elevated extracellular [K+] instead leads to a transient neuronal silence that is not due to depolarization block (Fig. 8, blue boxes).

In the pyloric circuit, all local synaptic connections are inhibitory (Eisen and Marder 1982; Miller and Selverston 1982; Rosenbaum and Marder 2018). Synaptic transmission in the STG is both graded and spike mediated, meaning that action potentials are not required for inhibitory synapses to function (Graubard et al. 1980; Manor et al. 1997). Therefore, the observed decrease in both bursting and spiking activity in elevated extracellular [K+] could be caused by global depolarization leading to increased inhibition that initially suppresses spiking and bursting activity. In support of this theory, elevated [K+] did not have the same inhibitory effect on PD neurons with glutamatergic synapses blocked compared with PD neurons with intact synaptic connections. We speculate that similar blockades of circuit activity could occur whenever synaptic inhibition is strengthened. Moreover, in studies of proprioceptive neurons of the blue crab and the muscle receptor organ of the crayfish, increased [K+] also has an inhibitory effect at concentrations not thought to cause a depolarization block (Malloy et al. 2017).

Adaptation to Global Perturbation

The PD/AB pacemaker unit of the pyloric circuit exhibited rapid adaptation to the disruptive stimulus of increased extracellular [K+] (Fig. 8, pink boxes). Although the triphasic pyloric rhythm was not fully restored in 2.5×[K+] saline, PD neurons exhibited rapid changes in excitability over several minutes, which corresponded to the recovery of spiking and, in many cases, bursting activity. This time course is similar to the rapid increase of neurotransmitter release in Drosophila neurons following glutamate receptor blockade, which also occurs within minutes and does not require protein synthesis (Frank et al. 2006).

The time course of adaptation in the present study contrasts with many examples of homeostatic plasticity in which loss of activity elicits changes in gene expression to restore activity that are thought to occur over hours to days (Cudmore and Turrigiano 2004; Desai et al. 1999; Turrigiano 2012). Such mechanisms can be induced by changes in extracellular [K+]. Rat myenteric neurons cultured in elevated [K+] serum for several days exhibit long-lasting changes in Ca2+ channel function (Franklin 1992). Similarly, culturing rat hippocampal pyramidal cells in high-[K+] medium for several days leads to activation of calcium-dependent changes in the intrinsic excitability of the neurons that can be seen in changes in the input resistance and the resting membrane potential (O’Leary et al. 2010).

Changes in K+ channel densities are often associated with activity-dependent regulation of neuronal activity. For example, depolarization of crustacean motor neurons with current pulses for several hours alters K+ channel densities in a cell-specific manner through a calcium-dependent mechanism (Golowasch et al. 1999). Adaptation to global perturbation over several hours to days is well described by computational models via calcium signals that influence expression levels of ion channels (O’Leary 2018; O’Leary et al. 2014).

In the STNS, the upstream commissural ganglia and the esophageal ganglion release a wide range of neuromodulators onto the STG that affect excitability of cells and the pyloric rhythm (Marder 2012; Marder and Bucher 2007). Pyloric neurons in the STG also exhibit a form of long-term adaptation in response to removal of these modulatory inputs. Some preparations in which neuromodulatory inputs are removed initially lose rhythmicity and gradually recover over the course of several days (Gray et al. 2017; Gray and Golowasch 2016; Luther et al. 2003; Thoby-Brisson and Simmers 1998, 2002). Nonetheless, when preparations remain active after removal of neuromodulatory inputs, they tend to maintain a level of activity similar to that shown in preparations that recover after losing activity (Hamood et al. 2015), suggesting that there may be a target activity level for the circuit.

The rapid adaptation of PD neurons in elevated extracellular [K+] is most likely due to cell intrinsic conductance changes (Fig. 8, pink boxes). In crustacean motor neurons, cell-intrinsic changes in A-type (IA) and Ca2+-activated K+ channel (IKCa) current densities can be rapidly modulated by second-messenger kinase pathways activated by global depolarization (Ransdell et al. 2012). Interestingly, there was no discernable effect of removing upstream modulation on the response of PD neurons to elevated [K+]. In addition, PD neurons display an adaptive response even when isolated from local presynaptic inputs with PTX. Taken together, these data suggest that the adaptation of PD neurons is likely due to a cell-intrinsic response, altering conductances to allow for recovery of spiking and bursting behavior. Given the complexity and heterogeneity of conductances that underlie the pyloric rhythm, it is difficult to speculate which specific conductances could be responsible for the observed recovery. Future studies could make use of computer modeling of STG motor neurons using genetic algorithms and currentscapes to determine conditions under which such adaptation is possible (Alonso and Marder 2019).

Variable Responses to Similar Perturbations

The effects of perturbations are often reported by averaging the results from a number of individuals, but this approach can be misleading (Golowasch et al. 2002). Within the STG, conductance densities and strengths of synaptic connections can vary two- to sixfold in magnitude between individuals (Alonso and Marder 2019; Goaillard et al. 2009; Schulz et al. 2006, 2007; Shruti et al. 2014; Temporal et al. 2014). Variability in neuronal conductances underlying similar activity patterns has also been demonstrated across phyla (Nelson and Turrigiano 2008; Roffman et al. 2012; Swensen and Bean 2005; Tran et al. 2019). In addition, computational modeling of the pyloric network has revealed that multiple combinations of parameters can give rise to similar activity patterns (Goldman et al. 2001; Marder et al. 2015; O’Leary et al. 2014; Prinz et al. 2004; Taylor et al. 2009).

Circuits and individual neurons with apparently identical outputs under control conditions can present distinctly different responses to perturbation due to underlying differences in network parameters (Alonso and Marder 2019; Haddad and Marder 2018; Haley et al. 2018; Hamood and Marder 2014; Tang et al. 2012). In this study we observed a range in the time course of adaptive response to the same perturbation, which may suggest individual parameter differences that are not evident in control conditions. The application of elevated [K+] saline to identified STG neurons provides additional evidence that differences in individual conductance parameters can influence responses to global perturbation (Alonso and Marder 2019).

Potential Implications for Disease States

Hyperkalemia is associated with a number of human disease states. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) leads to increases in serum [K+] up to three times the normal levels, directly affecting neuronal excitability and changes in neuronal properties (Arnold et al. 2014; Krishnan and Kiernan 2009). Similarly, increased activity of a group of neurons can increase the extracellular [K+] in the surrounding tissue (Baylor and Nicholls 1969; Kríz et al. 1974; Octeau et al. 2019) and epileptic seizures and brain trauma can lead to increases in [K+] in surrounding brain regions (Fröhlich et al. 2008; Katayama et al. 1990; Moody et al. 1974; Silver and Erecińska 1994). In this study we showed that changes in extracellular potassium concentration similar to those reported in pathological conditions produce not only immediate change in the activity of STG motor neurons but also long-lasting changes in the intrinsic properties of these neurons. Transient changes in extracellular [K+] have been shown to cause long-lasting changes in the organization and phosphorylation pattern of K+ channels (Misonou et al. 2004), which could lead to long-lasting changes in circuit function (Rodgers et al. 2007; Somjen 2001, 2002).

Reassessing Global Perturbation

The results of this study highlight the lack of a consistent response to a seemingly simple perturbation. In this classical manipulation of increased extracellular [K+], we observed a paradoxical decrease in the activity of PD neurons upon bath application of high [K+], followed by a recovery of activity in a short period of time. Despite knowing the network connectivity, circuit properties and expected behavior of identified neurons within the STG, we were still unable to a priori predict or fully explain the effects of increased [K+] on circuit performance. The complex interaction between circuit level effects and cell intrinsic responses to simple changes in ion concentrations underscores the importance of assessing and reporting neuronal activity during such manipulations in any experiment.

GRANTS

This work was supported by NIH Grants R35 NS097343 and R90 DA033463.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.S.H., M.C.R., E.O.M., and E.M. conceived and designed research; L.S.H., M.C.R., E.O.M., D.J.P., E.J.J., and M.K. performed experiments; L.S.H., M.C.R., E.O.M., D.J.P., and E.J.J. analyzed data; L.S.H., M.C.R., E.O.M., D.J.P., and E.M. interpreted results of experiments; E.O.M. prepared figures; L.S.H., M.C.R., and E.M. drafted manuscript; L.S.H., M.C.R., E.O.M., D.J.P., E.J.J., M.K., and E.M. edited and revised manuscript; L.S.H., M.C.R., E.O.M., D.J.P., E.J.J., M.K., and E.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ENDNOTE

At the request of the authors, readers are herein alerted to the fact that additional materials related to this manuscript may be found at https://github.com/marderlab. These materials are not a part of this manuscript, and have not undergone peer review by the American Physiological Society (APS). APS and the journal editors take no responsibility for these materials, for the website address, or for any links to or from it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Daniel Shin for assistance with dissections and Dr. Stephen Van Hooser for statistical advice. Drs. Sonal Kedia and Jason Pipkin gave us comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Alonso LM, Marder E. Visualization of currents in neural models with similar behavior and different conductance densities. eLife 8: e42722, 2019. doi: 10.7554/eLife.42722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold R, Pussell BA, Howells J, Grinius V, Kiernan MC, Lin CSY, Krishnan AV. Evidence for a causal relationship between hyperkalaemia and axonal dysfunction in end-stage kidney disease. Clin Neurophysiol 125: 179–185, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2013.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerini L, Galante M, Grandolfo M, Nistri A. Generation of rhythmic patterns of activity by ventral interneurones in rat organotypic spinal slice culture. J Physiol 517: 459–475, 1999. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0459t.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA, Nicholls JG. Changes in extracellular potassium concentration produced by neuronal activity in the central nervous system of the leech. J Physiol 203: 555–569, 1969. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidaut M. Pharmacological dissection of pyloric network of the lobster stomatogastric ganglion using picrotoxin. J Neurophysiol 44: 1089–1101, 1980. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.6.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg JP. Maximum entropy spectral analysis. Proc 37th Meeting Society of Exploration Geophysicists, Oklahoma City, OK, October 31, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Buttkus B. Spectral Analysis and Filter Theory. Berlin: Springer, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvette S, Soltani S, Seigneur J, Timofeev I. In vivo models of cortical acquired epilepsy. J Neurosci Methods 260: 185–201, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cudmore RH, Turrigiano GG. Long-term potentiation of intrinsic excitability in LV visual cortical neurons. J Neurophysiol 92: 341–348, 2004. doi: 10.1152/jn.01059.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Turrigiano GG. Plasticity in the intrinsic excitability of cortical pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci 2: 515–520, 1999. doi: 10.1038/9165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JS, Marder E. Mechanisms underlying pattern generation in lobster stomatogastric ganglion as determined by selective inactivation of identified neurons. III. Synaptic connections of electrically coupled pyloric neurons. J Neurophysiol 48: 1392–1415, 1982. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.6.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank CA, Kennedy MJ, Goold CP, Marek KW, Davis GW. Mechanisms underlying the rapid induction and sustained expression of synaptic homeostasis. Neuron 52: 663–677, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin JL. Long-term regulation of neuronal calcium currents by prolonged changes of membrane potential. J Neurosci 12: 1726–1735, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich F, Bazhenov M, Iragui-Madoz V, Sejnowski TJ. Potassium dynamics in the epileptic cortex: new insights on an old topic. Neuroscientist 14: 422–433, 2008. doi: 10.1177/1073858408317955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goaillard JM, Taylor AL, Schulz DJ, Marder E. Functional consequences of animal-to-animal variation in circuit parameters. Nat Neurosci 12: 1424–1430, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nn.2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MS, Golowasch J, Marder E, Abbott LF. Global structure, robustness, and modulation of neuronal models. J Neurosci 21: 5229–5238, 2001. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-14-05229.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golowasch J, Abbott LF, Marder E. Activity-dependent regulation of potassium currents in an identified neuron of the stomatogastric ganglion of the crab Cancer borealis. J Neurosci 19: RC33, 1999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-j0004.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golowasch J, Goldman MS, Abbott LF, Marder E. Failure of averaging in the construction of a conductance-based neuron model. J Neurophysiol 87: 1129–1131, 2002. doi: 10.1152/jn.00412.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubard K. Synaptic transmission without action potentials: input-output properties of a nonspiking presynaptic neuron. J Neurophysiol 41: 1014–1025, 1978. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.4.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graubard K, Raper JA, Hartline DK. Graded synaptic transmission between spiking neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77: 3733–3735, 1980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.6.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M, Daudelin DH, Golowasch J. Activation mechanism of a neuromodulator-gated pacemaker ionic current. J Neurophysiol 118: 595–609, 2017. doi: 10.1152/jn.00743.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M, Golowasch J. Voltage dependence of a neuromodulator-activated ionic current. eNeuro 3: ENEURO.0038-16.2016, 2016. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0038-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez GJ, Grashow RG. Cancer borealis stomatogastric nervous system dissection. J Vis Exp: 1207, 2009. doi: 10.3791/1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad SA, Marder E. Circuit robustness to temperature perturbation is altered by neuromodulators. Neuron 100: 609–623.e3, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley JA, Hampton D, Marder E. Two central pattern generators from the crab, Cancer borealis, respond robustly and differentially to extreme extracellular pH. eLife 7: e41877, 2018. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamood AW, Haddad SA, Otopalik AG, Rosenbaum P, Marder E. Quantitative reevaluation of the effects of short- and long-term removal of descending modulatory inputs on the pyloric rhythm of the crab, Cancer borealis. eNeuro 2: ENEURO.0058-14.2015, 2015. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0058-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamood AW, Marder E. Animal-to-animal variability in neuromodulation and circuit function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 79: 21–28, 2014. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2014.79.024828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Warrick RM. General principles of rhythmogenesis in central pattern generator networks. Prog Brain Res 187: 213–222, 2010. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53613-6.00014-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartigan JA, Hartigan PM. The dip test of unimodality. Ann Stat 13: 70–84, 1985. doi: 10.1214/aos/1176346577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartline DK, Gassie DV Jr. Pattern generation in the lobster (Panulirus) stomatogastric ganglion. I. Pyloric neuron kinetics and synaptic interactions. Biol Cybern 33: 209–222, 1979. doi: 10.1007/BF00337410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper SL, Thuma JB, Guschlbauer C, Schmidt J, Büschges A. Cell dialysis by sharp electrodes can cause nonphysiological changes in neuron properties. J Neurophysiol 114: 1255–1271, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.01010.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen MS, Yaari Y. Role of intrinsic burst firing, potassium accumulation, and electrical coupling in the elevated potassium model of hippocampal epilepsy. J Neurophysiol 77: 1224–1233, 1997. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.77.3.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katayama Y, Becker DP, Tamura T, Hovda DA. Massive increases in extracellular potassium and the indiscriminate release of glutamate following concussive brain injury. J Neurosurg 73: 889–900, 1990. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.6.0889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan AV, Kiernan MC. Neurological complications of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Neurol 5: 542–551, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kríz N, Syková E, Ujec E, Vyklický L. Changes of extracellular potassium concentration induced by neuronal activity in the spinal cord of the cat. J Physiol 238: 1–15, 1974. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Bloodgood BL, Hauser JL, Lapan AD, Koon AC, Kim TK, Hu LS, Malik AN, Greenberg ME. Activity-dependent regulation of inhibitory synapse development by Npas4. Nature 455: 1198–1204, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature07319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luther JA, Robie AA, Yarotsky J, Reina C, Marder E, Golowasch J. Episodic bouts of activity accompany recovery of rhythmic output by a neuromodulator- and activity-deprived adult neural network. J Neurophysiol 90: 2720–2730, 2003. doi: 10.1152/jn.00370.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy C, Dayaram V, Martha S, Alvarez B, Chukwudolue I, Dabbain N, Mahmood DD, Goleva S, Hickey T, Ho A, King M, Kington P, Mattingly M, Potter S, Simpson L, Spence A, Uradu H, Van Doorn J, Weineck K, Cooper RL. The effects of potassium and muscle homogenate on proprioceptive responses in crayfish and crab. J Exp Zool A Ecol Integr Physiol 327: 366–379, 2017. doi: 10.1002/jez.2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manor Y, Nadim F, Abbott LF, Marder E. Temporal dynamics of graded synaptic transmission in the lobster stomatogastric ganglion. J Neurosci 17: 5610–5621, 1997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-14-05610.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E. Neuromodulation of neuronal circuits: back to the future. Neuron 76: 1–11, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Bucher D. Central pattern generators and the control of rhythmic movements. Curr Biol 11: R986–R996, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Bucher D. Understanding circuit dynamics using the stomatogastric nervous system of lobsters and crabs. Annu Rev Physiol 69: 291–316, 2007. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.031905.161516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Calabrese RL. Principles of rhythmic motor pattern generation. Physiol Rev 76: 687–717, 1996. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Eisen JS. Transmitter identification of pyloric neurons: electrically coupled neurons use different transmitters. J Neurophysiol 51: 1345–1361, 1984. doi: 10.1152/jn.1984.51.6.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Goaillard JM. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 563–574, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrn1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Goeritz ML, Otopalik AG. Robust circuit rhythms in small circuits arise from variable circuit components and mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurobiol 31: 156–163, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard DM. Simpler networks. Ann N Y Acad Sci 193: 59–72, 1972. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1972.tb27823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JP, Selverston AI. Mechanisms underlying pattern generation in lobster stomatogastric ganglion as determined by selective inactivation of identified neurons. IV. Network properties of pyloric system. J Neurophysiol 48: 1416–1432, 1982. doi: 10.1152/jn.1982.48.6.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misonou H, Mohapatra DP, Park EW, Leung V, Zhen D, Misonou K, Anderson AE, Trimmer JS. Regulation of ion channel localization and phosphorylation by neuronal activity. Nat Neurosci 7: 711–718, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nn1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody WJ Jr, Futamachi KJ, Prince DA. Extracellular potassium activity during epileptogenesis. Exp Neurol 42: 248–263, 1974. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(74)90023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison B 3rd, Elkin BS, Dollé JP, Yarmush ML. In vitro models of traumatic brain injury. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 13: 91–126, 2011. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071910-124706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SB, Turrigiano GG. Strength through diversity. Neuron 60: 477–482, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris BJ, Wenning A, Wright TM, Calabrese RL. Constancy and variability in the output of a central pattern generator. J Neurosci 31: 4663–4674, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5072-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary T. Homeostasis, failure of homeostasis and degenerate ion channel regulation. Curr Opin Physiol 2: 129–138, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cophys.2018.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary T, Williams AH, Franci A, Marder E. Cell types, network homeostasis, and pathological compensation from a biologically plausible ion channel expression model. Neuron 82: 809–821, 2014. [Erratum in Neuron 88: 1308, 2015]. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary T, van Rossum MC, Wyllie DJ. Homeostasis of intrinsic excitability in hippocampal neurones: dynamics and mechanism of the response to chronic depolarization. J Physiol 588: 157–170, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.181024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Octeau JC, Gangwani MR, Allam SL, Tran D, Huang S, Hoang-Trong TM, Golshani P, Rumbell TH, Kozloski JR, Khakh BS. Transient, consequential increases in extracellular potassium ions accompany channelrhodopsin2 excitation. Cell Reports 27: 2249–2261.e7, 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.04.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panaitescu B, Ruangkittisakul A, Ballanyi K. Silencing by raised extracellular Ca2+ of pre-Bötzinger complex neurons in newborn rat brainstem slices without change of membrane potential or input resistance. Neurosci Lett 456: 25–29, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pinzón MA, Tao L, Nicholson C. Extracellular potassium, volume fraction, and tortuosity in rat hippocampal CA1, CA3, and cortical slices during ischemia. J Neurophysiol 74: 565–573, 1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.2.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz AA, Bucher D, Marder E. Similar network activity from disparate circuit parameters. Nat Neurosci 7: 1345–1352, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nn1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransdell JL, Nair SS, Schulz DJ. Rapid homeostatic plasticity of intrinsic excitability in a central pattern generator network stabilizes functional neural network output. J Neurosci 32: 9649–9658, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1945-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers CI, Armstrong GA, Shoemaker KL, LaBrie JD, Moyes CD, Robertson RM. Stress preconditioning of spreading depression in the locust CNS. PLoS One 2: e1366, 2007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roffman RC, Norris BJ, Calabrese RL. Animal-to-animal variability of connection strength in the leech heartbeat central pattern generator. J Neurophysiol 107: 1681–1693, 2012. doi: 10.1152/jn.00903.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum P, Marder E. Graded transmission without action potentials sustains rhythmic activity in some but not all modulators that activate the same current. J Neurosci 38: 8976–8988, 2018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2632-17.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruangkittisakul A, Panaitescu B, Ballanyi K. K+ and Ca2+ dependence of inspiratory-related rhythm in novel “calibrated” mouse brainstem slices. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 175: 37–48, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak IA, Molkov YI, Jasinski PE, Shevtsova NA, Smith JC. Rhythmic bursting in the pre-Bötzinger complex: mechanisms and models. Prog Brain Res 209: 1–23, 2014. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63274-6.00001-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz DJ, Goaillard JM, Marder E. Variable channel expression in identified single and electrically coupled neurons in different animals. Nat Neurosci 9: 356–362, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nn1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz DJ, Goaillard JM, Marder EE. Quantitative expression profiling of identified neurons reveals cell-specific constraints on highly variable levels of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 13187–13191, 2007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705827104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selverston AI, Miller JP. Mechanisms underlying pattern generation in lobster stomatogastric ganglion as determined by selective inactivation of identified neurons. I. Pyloric system. J Neurophysiol 44: 1102–1121, 1980. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.6.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma N, Gabel HW, Greenberg ME. A shortcut to activity-dependent transcription. Cell 161: 1496–1498, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shruti S, Schulz DJ, Lett KM, Marder E. Electrical coupling and innexin expression in the stomatogastric ganglion of the crab Cancer borealis. J Neurophysiol 112: 2946–2958, 2014. doi: 10.1152/jn.00536.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver IA, Erecińska M. Extracellular glucose concentration in mammalian brain: continuous monitoring of changes during increased neuronal activity and upon limitation in oxygen supply in normo-, hypo-, and hyperglycemic animals. J Neurosci 14: 5068–5076, 1994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-05068.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somjen GG. Mechanisms of spreading depression and hypoxic spreading depression-like depolarization. Physiol Rev 81: 1065–1096, 2001. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.3.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somjen GG. Ion regulation in the brain: implications for pathophysiology. Neuroscientist 8: 254–267, 2002. doi: 10.1177/1073858402008003011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swensen AM, Bean BP. Robustness of burst firing in dissociated Purkinje neurons with acute or long-term reductions in sodium conductance. J Neurosci 25: 3509–3520, 2005. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3929-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LS, Goeritz ML, Caplan JS, Taylor AL, Fisek M, Marder E. Precise temperature compensation of phase in a rhythmic motor pattern. PLoS Biol 8: e1000469, 2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang LS, Taylor AL, Rinberg A, Marder E. Robustness of a rhythmic circuit to short- and long-term temperature changes. J Neurosci 32: 10075–10085, 2012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1443-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AL, Goaillard JM, Marder E. How multiple conductances determine electrophysiological properties in a multicompartment model. J Neurosci 29: 5573–5586, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4438-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temporal S, Lett KM, Schulz DJ. Activity-dependent feedback regulates correlated ion channel mRNA levels in single identified motor neurons. Curr Biol 24: 1899–1904, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoby-Brisson M, Simmers J. Neuromodulatory inputs maintain expression of a lobster motor pattern-generating network in a modulation-dependent state: evidence from long-term decentralization in vitro. J Neurosci 18: 2212–2225, 1998. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02212.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]