Abstract

Objective

To study the central nervous system (CNS) complications in patients with COVID-19 infection especially among Native American population in the current pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus (COVID-19).

Methods

Patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection at University of New Mexico hospital (UNMH) were screened for development of neurological complications during Feb 01 to April 29, 2020 via retrospective chart review.

Results

Total of 90 hospitalized patients were screened. Out of seven patients, majority were Native Americans females, and developed neurological complications including subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), Intraparenchymal hemorrhage (IPH), Ischemic stroke (IS) and seizure. All 7 patients required Intensive care unit (ICU) level of care. Patients who developed CNS complications other than seizure were females in the younger age group (4 patients, 38-58 years) with poor outcome. Out of 7, three developed subarachnoid hemorrhage, two developed ischemic infarction, and four developed seizure. Two patients with hemorrhagic complication expired during the course of hospitalization. All three patients with seizure were discharged to home.

Conclusion

Patients with serious CNS complications secondary to COVID-19 infection were observed to be Native Americans. Patients who developed hemorrhagic or ischemic events were observed to have poor outcomes as compared to patients who developed seizures.

Key Words: COVID-19, stroke, Seizures, Native Americans

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), termed as COVID-19 has affected millions of people worldwide. It originated in the city of Wuhan, China and was formally declared as a pandemic by World Health Organization (WHO) on March 11th 2020. It has affected more than five million people and more than 100,000 deaths so far in United States.1

Neurological complications seen in COVD-19 include involvement of both central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS). According to a recent study, neurological symptoms were seen in approximately 36% of the patients diagnosed with COVID-19.2 Commonly reported CNS symptoms were dizziness, headache, metabolic encephalopathy, taste impairment, smell impairment, vision impairment and neuralgia. Serious neurological complications such as stroke, and seizure, were also reported.2 , 3 Recent weekly report by centers for disease control and prevention (CDC) reported 0.7% of the US population experienced central nervous system (CNS) complications.4

We share a case series of seven patients, all except one of whom, were Native Americans (NA), and experienced CNS complications during the admission of COVID-19.

Methods

Retrospective chart review of patients, admitted to University of New Mexico Health Science Center (UNMH) between Feb 01 to April 29, 2020, was done. Patients diagnosed with COVID-19 via reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from nasal swab were screened for development of neurological complications (ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, sub-arachnoid hemorrhage, seizure, and encephalitis). Patients with peripheral neurological symptoms such as nerve pain, tingling and/or minor CNS symptoms like headache, mild dizziness, altered mental status without focal neurological signs, or metabolic encephalopathy, were excluded. The study was approved by UNMH institutional review board and was granted a waiver of informed consent (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 ).

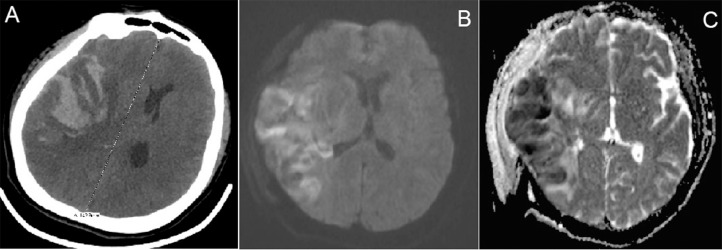

Fig. 1.

(Case # 2): (A) Non-contrast CT- head axial section showing right cerebral hemispheric hypo-attenuation with hemorrhagic transformation (B) Diffusion weighted image (DWI) axial section and (B) Apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) axial image of post- hemi-craniectomy MRI brain without contrast showing acute ischemic stroke involving right cerebral hemisphere

Fig. 2.

(Case # 3): MRI brain without contrast (A) DWI axial image and (B) ADC axial image showing acute infarct in right cerebellar hemisphere. Figure I (Case # 1): Non-contrast CT head axial sections showing bilateral subarachnoid hemorrhage occupying cerebral sulci. Figure II (Case # 4): Non-contrast CT head showing right frontal and parietal hypo-attenuation with hemorrhagic transformation extending into bilateral lateral ventricles.

Results

A total of 90 patients with confirmed COVID-19 were screened. Out of 90 patients, 53(59%) were NA, 25(28%) were Caucasian, 4(4%) were African-American and 8(9%) were others. Seven out of ninety (8%) were found to have neurological manifestations including SAH, IPH, IS and seizures, were included. Mean age was 55 years and majority (5 out of 7) were female (See Table 1 ). Six patients were Native Americans (NA) and one was Caucasian. All patients presented with symptoms of COVID-19 infection including fever, cough, shortness of breath and general body malaise. Five patients required emergent intubation. All 7 patients required intensive care unit (ICU) level of care.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 cases presenting with neurological manifestations.

| Age | Case # 1 | Case # 2 | Case # 3 | Case #4 | Case # 5 | Case # 6 | Case # 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVA | Seizures | ||||||

| Age | 38 | 47 | 39 | 58 | 75 | 77 | 53 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Ethnicity | Native American | Native American | Native American | Native American | Native American | Caucasian | Native American |

| BMI | 55.0 | 27.5 | 23.5 | 24.3 | 29.0 | 25.3 | 22.4 |

| Comorbid medical conditions | Obesity, Asthma, Anxiety, Depression Diabetes |

Alcohol use disorder in remission | Hands and feet birth defect Diabetes |

No past medical history | Hypertension, Diabetes mellitus, complicated ventral hernia repair | Hypertension, Diabetes Mellitus, hyperlipidemia, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major depressive disorder | Alcohol use disorder in remission, traumatic brain injury |

| Home medications | Ibuprofen, Asthma inhalers, Monteleukast | None | None | None | Insulin, Lisinopril, Metformin, Aspirin | Metformin, Albuterol, Amitryptyline, Aspirin, Pregabalin, Tamsulosin, Furosemide | Escitalopram, Multivitamin |

| Presenting vitals | |||||||

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | 119/74 | 128/68 | 93/86 | 101/74 | 98/76 | 117/64 | 129/78 |

| Pulse (bpm) | 106 | 86 | 106 | 140 | 98 | 99 | 82 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.0 | 37.6 | 36.1 | 37.9 | 37.3 | 36.4 | 36.2 |

| O2 sat | 90% | 74 | 69 | 84 | 93 | 65 | 95% |

| COVID-19 presentation | Fever, cough, Shortness of Breath, chest pain, Chills, Myalgia | Fever, Cough, | Fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, fatigue | Fever, Cough, shortness of breath | Fever, Abdominal pain | Shortness of breath | Fever |

| Labs: | |||||||

| WBC (N/L %) | 10.7 (93/4) | 10.6 (81/11) | 20 (N/A) | 16.2 (N/A) | 6.8 (54/38) | 20 (91/3) | 15.1 (85/8) |

| Platelets | 263 | 302 | 342 | 239 | 370 | 225 | 227 |

| PT/INR (sec/ratio) | 13.2/1.1 | 15.3/1.3 | 11.4/1.0 | 13.0/1.1 | 15.0/1.3 | 12.6/1.1 | 12.6/1.1 |

| ESR (mm/hr) | 46 | 57 | 7.6 | N/A | N/A | 111 | N/A |

| CRP | 17.8 | 5.4 | 0.4 | N/A | N/A | 25.4 | <0.3 |

| LFTs | AST:295 | AST:28 | AST:22 | AST:101 | AST:70 | AST:148 | AST:24 |

| ALT:86 | ALT:26 | ALT:17 | ALT:75 | ALT:31 | ALT:45 | ALT:15 | |

| ALP:137 | ALP:60 | ALP:219 | ALP:85 | ALP:100 | ALP:129 | ALP:77 | |

| TB:0.5 | TB:1.0 | TB:0.6 | TB:0.5 | TB:0.9 | TB:0.4 | TB:1.0 | |

| TP:8 | TP:6.8 | TP:7 | TP:6.2 | TP:8.1 | TP:7 | TP:6.9 | |

| AlB:3 | AlB:2.5 | AlB:2.5 | AlB:1.9 | AlB:2.5 | AlB:2.1 | AlB:3.1 | |

| D-dimer (ng/ml) | 421 | 1,380 | 2,061 | 1,425 | 1,535 | 1,113 | 1,680 |

| Ferritin (ng/ml) | 397 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.3 | 6.3 | 16.8 | 5.9 | 10.0 | 6.6 | N/A |

| LDL (mg/dl) | N/A | 46 | 35 | N/A | 77 | 67 | N/A |

| Hyper-coagulable panel (U/ml) | N/A | N/A | Positive anti-cardiolipin | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Vasculitis panel (titre) | N/A | ANA, Anti-DNA positive | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ethanol Level | Not detected | Not detected | Not detected | Not done | Not done | Not detected | Not detected |

| Urine Toxicology screen | N/A | N/A | Positive benzodiazepine | Not done | Not done | UDM: neg | Positive oxycodone |

| Chest Imaging Findings: | Multifocal pneumonia | Mild bibasilar atelectasis | Multifocal pneumonia | Multifocal pneumonia | Left ground glass opacity | Multifocal pneumonia | Bibasilar atelectasis |

| Emergent Intubation on presentation | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| DVT prophylaxis on presentation | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Onset of neurological symptoms from COVID symptoms | Day 16 | Day 6 | Day 5 | Day 19 | Day 7 | Day 3 | Day 16 |

| Neurological presentation | AMS, Not following commands, GCS: 2T1 | AMS, dilated pupil, GCS: 3T6 | AMS, Seizures, GCS: 2T6 | AMS, Fixed pupil, Not following commands, GCS:1T1 | AMS, Seizure | AMS, seizure | AMS, Status epilepticus |

| Neuro-imaging findings | |||||||

| NCCT | bilateral SAH | Right IPH with IVH and SAH | Not done | Right large IPH with IVH and SAH with midline shift and herniation. | Unremarkable | Non- specific right corona radiata calcificationq | Unremarkable |

| CTA Head & Neck | Not done | No LVO, AVM or dissection | No LVO or critical stenosis | Not done | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| MRI brain | Not done | Right cerebral hemisphere infarct with HT | Right cerebellar hemisphere infarct | Not done | No acute abnormality | No abnormality | No Abnormality |

| MRA or MRV brain | Not done (see supplementary figure 1) | Right sigmoid and transverse sinus thrombosis (See figure 1) | Not done (see figure 2) | Not done (see supplementary figure 2) | Not done | No sinus venous thrombosis, or critical stenosis, subtel vasogenic edema can be seen with seizures | Not done |

| Vascular territory involved in ischemic stroke | - | Right Middle Cerebral Artery | Left Middle Cerebral and Anterior Cerebral Artery | Right Posterior Inferior Cerebellar Artery | - | - | - |

| EKG findings on admission | Sinus tachycardia with non-specific T wave abnormalities | Normal Sinus rhythm with prolonged Qtc of 495 | Sinus tachycardia with left axis deviation | Sinus tachycardia with left axis deviation and low voltage QRS complexes | NSR with no specific ST changes unchanged from prior EKG | NSR with PVCs | NSR with prolonged QTC of 533 |

| EEG Findings | Non-epileptiform activity | Not done | Burst suppression, no epileptiform activity | Not done | No interictal epileptiform or seizure activity | Low amplitude diffuse theta and delta with superimposed beta activity | No epileptiform activity |

| Treatment of neurological disease | BP control | Anticoagulation, BP control, seizure prophylaxis | Antiepileptic, Anticoagulation and high intensity statin | Antiplatelet and Statin | Antiepileptic and sedation | Antiepileptic and sedation | Antiepileptic and sedation |

| Neurological intervention | None | Emergent decompressive hemicraniectomy with anterior temporal lobectomy and evacuation of IPH | None | Emergent decompressive hemicraniectomy | None | None | None |

| Length of stay (ICU) (days) | 19 (17) Expired |

13 (3) Discharged SNF |

N/A Still admitted |

14 (14) Expired |

11 (3) Discharged |

16 (14) Discharged |

6 (2) Discharged |

Table Legend: AMS: altered mental status, BMI: body mass index, BP: blood pressure, CVA: cerebrovascular accident, HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c, ICU: intensive care unit, LDL: low density lipoprotein, MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, MRA: magnetic resonance angiogram, NCCT: non-contrast Computed Tomography scan, O2 sat: oxygen saturation, P: pulse, PT/INR: prothrombin time/international normalized ratio, T: temperature, WBC: white blood cell count.

Reference Ranges: WBC: 4-11 × 103 /µl, Hgb: 12-16 g/dl, Platelet count: 150-400 × 103 /µl, PT: 9.4-15.4 sec, INR: 0.80-1.30, aPTT: 26-38 sec, Anti-DNA: 0-4 IU/ml, D-dimer: 0-500 ng/ml, Fibrinogen: 170-450 mg/dl, TG: <150 mg/dl, LDL: <100 mg/dl, HDL: >40 mg/dl, Cholesterol: <200 mg/dl, HgbA1c: >6.5%, Anti-cardiolipin antibodies: 0.0-9.9U/ml, Procalcitonin: <10ng/ml, Ferritin: 30-530 ng/ml, Platelet count: 150-450k C-Reactive Protein: <0.3 mg/dl, Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate:0-28mm/hr, neutrophil E3/uL 1.8-7, lymphocyte 1 – 3.4 E3/ul, AST 6-58 Unit/Liter, ALT 14-67 Unit/Liter, ALP 38-150 Unit/Liter, Total Bili 0.3-1.2 mg/dl, Total protein 6.1-8.2 g/dl, albumin 3.4-4.7 g/dl.

The first four presenting with SAH, IPH, and IS, were NA females with age range 38 – 58 years. All presented with subjective fevers, shortness of breath and cough. The neurological complication in these four patients was observed between 5-19 days of symptoms onset. Out of other three cases presenting with seizure, two were NA with age range 53-77 years. All three patients required intubation on presentation but two patients required it for seizure and were extubated within 2 days.

All seven patients were on deep venous thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis with heparin since admission and this was continued appropriately as per clinical needs. None of the patients were treated with therapeutic anticoagulation. Overall length of stay was between 6-19 days and 2-17 days for ICU stay.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report sharing neurological complications in NA with COVID-19 infection. Native Americans, who make up less than 2 percent of the U.S. population, comprise 10 % of the population in state of New Mexico. Based on the CDC data, mortality among NA is higher compared to other ethnicities.4 In recent reports, it was acknowledged that due to health care disparities and low socioeconomic status, NA were at increased risk of having conditions associated with COVID-19.5 Moreover, in general population, NA have a higher incidence of Cerebrovascular accidents (CVA) compared to other ethnic groups.6 Approximately 59% of patients managed at our center for COVID-19 infection were NA (51 out of 90) and 6 out of 7 patients with neurological complication were NA. Even though we have a small sample size, our data depicts a higher prevalence of neurological manifestations among NA with COVID-19. We believe that this is due to the known higher prevalence of vascular risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, obesity, and alcohol abuse among the NA.6

It is also worth noting that our patients had some unusual findings, especially the presence of IPH. We could not ascertain why our NA patients had a higher incidence of brain bleeds. Klok et al. suggested that patients with severe COVID-19 have higher risk of thromboembolism due to procoagulant state.7 Three out of four patients who had CVA, one was found to have venous sinus thrombosis. All of them had elevated d-dimer levels. None of these patients had any atrial arrhythmias or evidence of unstable thrombus or plaques. The ischemic stroke can be partly explained due to pro-thrombotic state with dysregulation of the clotting system secondary to intense inflammation related to cytokine storm leading to thrombus formation.8 It might be possible that dysregulation of the clotting cascade might have resulted in hemorrhagic transformation. This same mechanism might be responsible for development of spontaneous SAH, though bleeding at other sites were not observed. None of the patients reported in our study or in prior published manuscripts have had subcortical strokes, which negates accelerated atherosclerosis as the cause of stroke in COVID-19 patients.

The three patients in our case series who experienced seizures had underlying risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes and/or history of alcohol abuse. We hypothesize that development of seizure was a secondary response from the underlying severe systemic illness. For all three patients, any structural lesion, vascular abnormality, metabolic cause, toxin induced or infectious etiology other than COVID-19 infection was ruled out. A recent study from China, demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 was present in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with COVID -19 by genome sequencing.9 A recently published case report from Japan did find viral RNA sequencing from CSF and claimed that the patient had meningitis who presented with seizures.10 Since most of our patients made clinical recovery with supportive care, further invasive neurological investigation including CSF analyses was not performed, though initial brain imaging and electroencephalogram (EEG) was benign in all three patients.

The understanding of the pathophysiology behind neural involvement in COVID-19 is still in its infancy but various mechanisms have been proposed. Zhao, et al postulated that the virus binds to Angiotensin converting enzyme-2 (ACE2) receptors which are also present in vascular endothelial cells in the brain.11 This is one of the potential mechanisms, how viruses can breach the blood brain barrier. Giacomelli et al showed presence of anosmia and dysgeusia as one of the early presenting symptoms suggesting involvement of olfactory and gustatory pathway.12 Further investigations are needed to confirm the exact pathophysiology.

Our study has some limitations. It is a single center retrospective study and this data might not be applicable to the general population as the majority of our patients are NA.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None

References

- 1.Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center - Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Accessed May 11, 2020. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/MAP.HTML

- 2.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. Published online April 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S. Large-Vessel Stroke as a Presenting Feature of Covid-19 in the Young. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. Published online April 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC COVID-19 Response Team Preliminary Estimates of the Prevalence of Selected Underlying Health Conditions Among Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 - United States, February 12-March 28, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):382–386. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raifman MA, Raifman JR. Disparities in the Population at Risk of Severe Illness From COVID-19 by Race/Ethnicity and Income. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(1):137–139. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jillella DV, Uchino K, Hatcher L. Abstract TMP49: Increasing Prevalence of Cerebrovascular Risk Factors in Native Americans With Ischemic Stroke. Stroke. 2019;50(Suppl_1) ATMP49-ATMP49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. Published online April 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vinciguerra M, Romiti S, Greco E. Atherosclerosis as Pathogenetic Substrate for Sars-Cov2. “Cytokine Storm.”. 2020 doi: 10.3390/jcm9072095. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu Y, Xu X, Chen Z. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-Coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu C, Zheng M. Single-cell RNA expression profiling shows that ACE2, the putative receptor of Wuhan 2019-nCoV, has significant expression in the nasal, mouth, lung and colon tissues, and tends to be co-expressed with HLA-DRB1 in the four tissues. Published online 2020.

- 12.Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F. Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in SARS-CoV-2 patients: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa330. Published online March 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]