Abstract

Immunoglobulin Y (IgY) is an effective orally administered antibody used to protect against various intestinal pathogens, but which cannot tolerate the acidic gastric environment. In this study, IgY was microencapsulated by alginate (ALG) and coated with chitooligosaccharide (COS). A response surface methodology was used to optimize the formulation, and a simulated gastrointestinal (GI) digestion (SGID) system to evaluate the controlled release of microencapsulated IgY. The microcapsule formulation was optimized as an ALG concentration of 1.56% (15.6 g/L), COS level of 0.61% (6.1 g/L), and IgY/ALG ratio of 62.44% (mass ratio). The microcapsules prepared following this formulation had an encapsulation efficiency of 65.19%, a loading capacity of 33.75%, and an average particle size of 588.75 μm. Under this optimum formulation, the coating of COS provided a less porous and more continuous microstructure by filling the cracks on the surface, and thus the GI release rate of encapsulated IgY was significantly reduced. The release of encapsulated IgY during simulated gastric and intestinal digestion well fitted the zero-order and first-order kinetics functions, respectively. The microcapsule also allowed the IgY to retain 84.37% immune-activity after 4 h simulated GI digestion, significantly higher than that for unprotected IgY (5.33%). This approach could provide an efficient way to preserve IgY and improve its performance in the GI tract.

Keywords: Immunoglobulin Y (IgY), Microencapsulation, Chitooligosaccharide (COS), Response surface methodology (RSM), Controlled release, Simulated gastrointestinal digestion (SGID)

1. Introduction

Immunoglobulin Y (IgY) is a special antibody extracted from chicken egg yolks which contain about 6 g per egg (Pauly et al., 2011). Chicken IgY is considered a functional equivalent of IgG due to its same origin and similar structure (Kovacs-Nolan and Mine, 2012). However, it is reported to have a variety of advantages compared with mammalian IgG, including a higher yield, lower cost, stronger specificity, higher hydrophobicity, and more convenience (Carlander et al., 2000; Dávalos-Pantoja et al., 2000; Kovacs-Nolan and Mine, 2012). Hence, IgY has been widely applied in human and veterinary health as the functional food component (Xu et al., 2012), animal dietary ingredient (Scheraiber et al., 2019), diagnostic reagent (Cai et al., 2012), immuno-therapeutic antibody (Rahman et al., 2013), and toxin neutralizer (Xing et al., 2017). One of the most effective applications of IgY is, via oral delivery, to protect the intestinal tract from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium, Clostridium difficile, Helicobacter pylori, and other foodborne pathogens (Pereira et al., 2019). However, as a protein-based substance, IgY is sensitive and prone to lose its bioactivity in the gastric tract which has a very low pH and contains large amounts of proteinases (Bakhshi et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2017). Consequently, a protective strategy against the acidic gastric environment is needed to maximize retention of the bioactivity of orally administered IgY.

Microencapsulation is a promising protection strategy for orally delivered substances, to maintain their bioactivity in harsh environments and sustain their release to target sites (Anal et al., 2003; Li et al., 2019). Hence, it is widely used in food processing, pharmaceutical engineering, and bio-manufacturing. It has been reported that microencapsulation is a useful technology for the delivery of various bioactive immunoglobulins through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Lee et al., 2012). Since the pH values and enzymolysis environments in the stomach and intestine are very different, the wall material of the microcapsule should have pH-sensitive and swelling properties for the controlled release of core material (Bakhshi et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2017). Alginate (ALG), a natural polysaccharide composed of β-D -mannuronic acid and α-L-guluronic acid, is considered a satisfactory wall material with these properties (Bakhshi et al., 2017). It is also easy for ALG to form gels under normal conditions provided with only multivalent cations such as Ca2+ (Kumar Giri et al., 2012; Jeong et al., 2020), which is beneficial for preserving the activity of immunoglobulins. However, its loose network is an important drawback of ALG gel, which would cause the leakage of inclusions at low pH (Zhang et al., 2011). As a result, it is necessary to coat the ALG with another wall material to enhance the performance of microcapsules.

Chitooligosaccharide (COS) is a cationic polymer obtained from the hydrolysis of another natural polysaccharide, chitosan. Compared with chitosan, COS has a lower molecular weight (normally ≤10 kDa), a higher water solubility, and stronger versatile bioactivity (Ha et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2018), which makes it easier to form stable, elastic, and sustained-release capsules (Wang and He, 2010). Thus, as an efficient encapsulation material or drug carrier, COS is attracting increasing attention for the oral delivery of bioactive substances (Liu et al., 2018). Moreover, polycationic COS can attach to the polyanionic ALG gel and form a coating via electrostatic interaction-induced self-assembly (Wang and He, 2010; Chandika et al., 2015). In this way, a more stable and less porous network can be generated on the surface, allowing the COS-coated microcapsules to perform better in oral administration and GI release than many other encapsulation systems (Liu et al., 2018). Recently, COS-coated encapsulation has been widely applied in the controlled release of diverse bioactive inclusions, such as quercetin (Ha et al., 2013), astaxanthin (Liu et al., 2018), and genistein (Wang et al., 2019). However, its application in the microencapsulation and sustained release of antibodies such as IgY has rarely been reported.

The objective of this work was to prepare, optimize, characterize, and evaluate in vitro, the IgY-containing ALG microcapsules coated with COS. A two-step ionic gelation method was used to prepare the microcapsules. Response surface methodology (RSM) was conducted to optimize their formulation with the encapsulation efficiency (EE), loading capacity (LC), and average particle size (APS) as dependent variables. A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was used to observe the surface morphology, an optical microscope and a chromameter to detect the physical properties, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to determine the IgY immune-activity of the microcapsules. The controlled release of microencapsulated IgY was evaluated using a simulated GI digestion (SGID) system and release kinetics analysis. The information obtained from this study could provide practical support for the preservation of bioactivity of IgY and improve its performance in the GI environment.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

IgY powders were obtained from Zhejiang AGS Biotech Co., Ltd. (Huzhou, Zhejiang, China; retention rate of immune-activity ≥96%). Sodium ALG (50–800 cps, 1 cps=1 mPa·s) and COS (molecular weight ≤2000 Da) were bought from the Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) and the Golden Shell Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Taizhou, Zhejiang, China), respectively. The ELISA kit for chicken IgY was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd. (St. Louis, MO, USA). All other reagents were of analytical grade, including pepsin (1:3000) and trypsin (1:250), which were both purchased from Yuanye Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Preparation of microcapsules

The IgY-loaded microcapsules were prepared by a two-step ionic gelation method according to Gandomi et al. (2016) and Liu et al. (2018) with some modifications. In particular, the aqueous ALG solution was prepared by stirring at 60 °C using a water bath, and then cooling to room temperature prior to use. The IgY was suspended in 1.0%–1.8% (1%=10 g/L) aqueous ALG solution at an IgY/ALG ratio of 12.5%–87.5% (mass ratio). Subsequently, the mixture was extruded dropwise at a height of 10 cm into a 1% (10 g/L) CaCl2 solution through a syringe filter with a 0.2-mm flat needle. After gelation for 30 min in the CaCl2 solution, the beads were washed with deionized water and then immersed in 0.5%–2.5% (1%=10 g/L) aqueous COS solution for 40 min. Subsequently, the COS-coated beads were rinsed several times using distilled water and freeze-dried at −60 °C prior to use (ALPHA 1-4 LD, Martin Christ, Osterode, Germany).

2.3. Experimental design, optimization, and modelling

According to the methods of Zimet et al. (2018) and He et al. (2019) with some modifications, a three-factor and three-level Box-Behnken experimental design was applied to optimize the microcapsule formulation by RSM. The experimental design matrix is shown in Table 1. The ALG concentration (A), COS concentration (B), and IgY/ALG ratio (C) were studied as independent variables, while the EE, LC, and APS were selected as response variables. Three uncoded levels corresponding to the codes (−1, 0, 1) for each independent variable were chosen based on the one-factor-at-a-time experiment results. The Box-Behnken design matrix consisted of 17 experimental runs in random order, including 12 factorial points and 5 replicates at the center point, which allowed the estimation of a pure error sum of squares (Mohammadi et al., 2016). All response values of EE, LC, and APS were explained by multiple regressions to fit the second-order polynomial equation as follows:

Table 1.

Independent and response variables in the Box-Behnken design for the optimization of the formulation of microcapsules

| Independent variable | Level |

Response variable | Constraint | ||

| Low (−1) | Medium (0) | High (1) | |||

| A=ALG concentration (%, 1%=10 g/L) | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.8 | EE (%) | Maximize |

| B=COS concentration (%, 1%=10 g/L) | 0.0 | 0.5 | 1.0 | LC (%) | Maximize |

| C=IgY/ALG ratio (%, mass ratio) | 31.25 | 50.00 | 68.75 | APS (μm) | Minimize |

ALG: alginate; COS: chitooligosaccharide; IgY: immunoglobulin Y; EE: encapsulation efficiency; LC: loading capacity; APS: average particle size

, ,

|

(1) |

where Y is the measured response value, EE (%), LC (%), or APS (μm); A, B, and C represent the independent variables, the ALG concentration (%, 1%= 10 g/L), COS concentration (%, 1%=10 g/L), and IgY/ALG mass ratio (%), respectively; β0 is the vertical intercept; β1, β2, and β3 are the linear coefficients; β11, β22, and β33 represent the quadratic coefficients; β12, β13, and β23 represent the interaction coefficients.

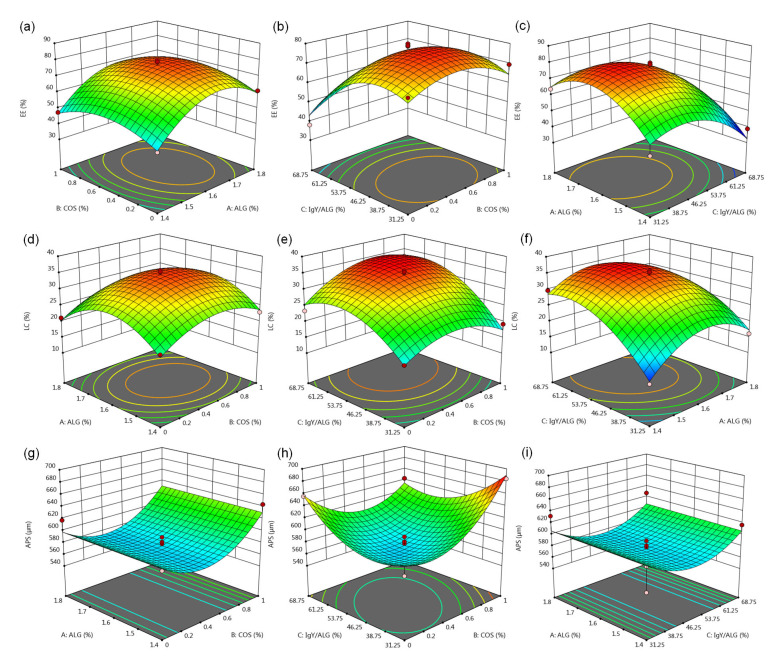

Assessments of the regression models were based on the P-values and R 2 values from analysis of variance (ANOVA). Statistical significance was confirmed when the P-value was of <0.05, while an extreme significance was established when the P-value was of <0.01. Three dimensional (3D) response surfaces were generated from the regression models and used for the determination of optimum conditions and the visualization of relationships between independent and response variables (Lu et al., 2008; Zimet et al., 2018).

2.4. Evaluation of EE and LC

The EE and LC of the microcapsules were detected according to the methods of Lian et al. (2016) and Bakhshi et al. (2017) with some modifications. Specifically, 0.2 g freeze-dried microcapsules were ground in a mortar using a pestle to destroy the wall material, and transferred into 10 mL 1 mol/L sodium citrate solution. Afterwards, samples were heated in a shaking water bath at 150 r/min for 2 h (COS-100B, Bilon Instruments Co., Ltd., China) until the IgY was fully released, followed by centrifugation at 4000 r/min for 20 min (TGL-16GA, Xingkekeji Instruments Co., Ltd., Changsha, China). After filtration, the IgY concentration in the supernatant was determined by a protein content assay at 280 nm using an ultraviolet (UV)-1750 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The supernatant of the IgY-unloaded microcapsule was adopted as the blank to correct the absorbance. The EE and LC values were calculated based on the following equations:

EE=C IgY V/M IgY×100%, (2)

LC=C IgY V/M×100%, (3)

where C IgY is the concentration of IgY in supernatant (g/mL), V is the volume of the sample solution (10 mL), M IgY is the total mass of the IgY powders used for the microcapsule preparation (g), and M is the total mass of IgY-loaded microcapsules used for the determination (0.2 g).

2.5. Measurement of APS, density, and sphericity

The APS of the samples was measured using a machine version method based on the studies of Igathinathane and Ulusoy (2016) and Wei et al. (2014) with slight modifications. Briefly, the samples were scattered on a glass plate and observed by an optical microscope coupled with an imaging system (BA410, Motic China Group Co., Ltd., Xiamen, China). Photographs of 10−15 particles were taken for each sample under the optical microscope, and then transformed first into grayscale and then into binary images by the ImageJ software V1.52s (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) using suitable threshold values. The Heywood diameter (equivalent circle diameter of projection) of the particles was calculated and the APS was determined by the following equation:

, ,

|

(4) |

where d is the Heywood diameter of each particle (μm) and ∑ means the summation of all particles of the same sample.

The density and sphericity of microcapsules were determined according to the method of Jeong et al. (2020) with slight modifications. Briefly, the density of a microcapsule was expressed as the ratio of weight to volume. The weight was the mean mass of 100–150 particles for each sample, while the volume was the equivalent sphere volume calculated based on the Heywood diameter. The sphericity was calculated as the ratio of the short-axis diameter to the long-axis diameter.

2.6. Color measurement

The color of the samples was measured using a chromameter (CR-400, Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan). The Commission Internationale de l'Eclairage (CIE) lightness, redness/greenness, and yellowness/blueness scales were directly detected, while the whiteness index was calculated following the method of Rosa-Sibakov et al. (2015) by the following equation:

, ,

|

(5) |

where W is the whiteness; L is the lightness, ranging from 0 to 100; a* is the redness/greenness (a*>0 represents red, whereas a*<0 means green); b* is the yellowness/blueness (b*>0 represents yellow, whereas b*<0 means blue).

2.7. SEM

The microstructure and surface morphology of samples were detected under a field emission SEM (FE-SEM; Regulus 8100, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The freeze-dried samples were mounted on a bronze stub and then sputter-coated with gold before observation. The observations were made at an accelerating voltage of 3.0 kV and a magnification of 5000.

2.8. Release behavior during simulated digestion

2.8.1 Simulated gastric digestion

Simulated gastric digestion (SGD) of samples was conducted according to the method of Bakhshi et al. (2017) with some modifications. A mount of 100 mg samples were dispersed in 10 mL distilled water and mixed with 0.3 mmol NaCl. After adjusting the pH to 1.2 with 1 mol/L HCl, 32 mg pepsin was added to the mixtures which were then incubated at 37 °C for 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, or 4 h, at a shaking speed of 150 r/min. Afterwards, the samples were centrifuged at 5000 r/min for 20 min and the IgY released in the supernatant was determined by UV spectroscopy, as described in Section 2.4.

2.8.2 Simulated intestinal digestion

Simulated intestinal digestion (SID) of samples was conducted according to the method of Ren et al. (2017) with some modifications. Briefly, 100 mg samples were dispersed in 10 mL distilled water and mixed with 0.5 mmol KH2PO4. The mixtures were adjusted to pH 6.8 with 1 mol/L HCl and/or 1 mol/L NaOH, and then 100 mg pepsin was added. Finally, the samples were incubated and centrifuged as described in Section 2.8.1, followed by IgY release measurement using the method described in Section 2.4.

2.8.3 SGID

The SGID of samples was conducted according to the method of Zhang et al. (2020) with minor modifications. Briefly, 100 mg samples were dispersed in 10 mL distilled water and mixed with 0.3 mmol NaCl. After adjusting the pH to 1.2 with 1 mol/L HCl, 32 mg pepsin was added to the mixtures which were then incubated at 37 °C for 0–2 h, with shaking at 150 r/min. Then, 0.5 mmol KH2PO4 was added to the samples which were then adjusted to pH 6.8 with 1 mol/L NaOH. After adding 100 mg pepsin, the mixtures were then incubated at 37 °C for another 0–2 h at a shaking speed of 150 r/min. Finally, the samples were centrifuged and assayed using the procedures described in Sections 2.8.1 and 2.4, respectively.

2.8.4 Release kinetics analysis

According to our previous studies (Zhang et al., 2016, 2017), four mathematical models were used to describe the release kinetics of IgY from microcapsules under different digestion conditions. These models include the zero-order kinetics function (Eq. (6)) (Eltayeb et al., 2015), Higuchi function (Eq. (7)) (Higuchi, 1963), Hixson-Crowell function (Eq. (8)) (Otsuka and Matsuda, 1996), and first-order kinetics function (Eq. (9)) (Mahasukhonthachat et al., 2010) as follows:

, ,

|

(6) |

, ,

|

(7) |

, ,

|

(8) |

, ,

|

(9) |

where t is the digestion time (h); R(t) is the IgY release from microcapsules after digestion for time t, (mg/g); R T is the LC of microcapsules (mg/g); R lim is the limiting IgY release, 0<R lim≤LC (mg/g); k0, kH, kHC, and k1 are IgY release constants, which can be determined by analysis of the regression between R(t) and t, mg/(g∙h) for k0, mg/(g∙h1/2) for kH, (mg/g)1/3∙h−1 for kHC, and h−1 for k1. A higher k0, kH, kHC, or k1 corresponds to a higher IgY release rate during digestion.

2.9. Detection of the relative immune-activity of IgY

The relative activity of the encapsulated IgY subjected to simulated digestion was detected by indirect ELISA following the methods of Bakhshi et al. (2017) and Ren et al. (2017) with slight modifications. The 96-well plates were coated with rabbit anti-chicken IgY, incubated overnight at 4 °C, and then blocked with 5% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH=7.4, 0.01 mol/L). After being washed with PBS with Tween 20 (PBST) three times, testing samples or untreated IgY (the control) was added to plates, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h in PBS. Afterward, plates were rinsed again and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-chicken IgY (1:2000) at 37 °C for another 2 h. The plates were then washed again with PBST several times and developed with o-phenylenediamine, followed by the detection of absorbance at 495 nm using a microplate reader (Type-190, Yaxu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). The immune-activity was expressed as a proportion of the activity of untreated IgY.

2.10. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Tables were made using Microsoft Excel 2016, while figures were drawn using Origin V8.0 (Origin-Lab, Northampton, MA, USA). One-way ANOVA and regression analysis were conducted using the SAS program V9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Carry, NC, USA), while the RSM was performed using Design-Expert software V11 (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Differences among mean values were established using Duncan’s multiple range test. A significant difference was confirmed when P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Optimization of microcapsule formulation

3.1.1 Single-factor results

The effects of ALG concentration on the EE, LC, and APS of IgY-loaded microcapsules are shown in Figs. 1a–1c). The concentration of ALG had a marked effect on the microencapsulation of IgY. As the ALG concentration was increased from 1.0% to 1.8%, the EE improved significantly from (31.11±1.11)% to (68.79±4.18)% (P<0.05; Fig. 1a), and the LC slowly improved from (22.18±0.79)% to (30.07±1.04)% (P<0.05), followed by a fall back to (23.44±1.42)% (P<0.05; Fig. 1b). The samples attained the highest EE and LC (P<0.05) as well as a relatively low APS (P<0.05) at an ALG concentration of 1.6%. Therefore, 1.6% (16 g/L) was considered the preliminary optimum ALG level.

Fig. 1.

Effects of ALG, COS, and IgY/ALG ratio on the EE, LC, and APS of IgY-loaded microcapsules

(a–c), (d–f), and (g–i) represent the alginate (ALG) concentration, chitooligosaccharide (COS) concentration, and immunoglobulin Y (IgY)/ALG ratio, respectively. (a), (d), and (g) represent the encapsulation efficiency (EE); (b), (e), and (h) represent the loading capacity (LC); (c), (f), and (i) represent the average particle size (APS). Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=3. Different lowercase letters above the error bar denote significant differences among the EE, LC, or APS as affected by different ALG concentrations, COS concentrations, or IgY/ALG ratios (P<0.05)

The effects of COS concentration on the EE, LC, and APS of IgY-loaded microcapsules are shown in Figs. 1d–1f. Briefly, during the increase of COS concentration from 0.5% to 2.5%, the EE decreased significantly from (74.65±2.12)% to (40.98±3.65)% (P<0.05), the LC was reduced dramatically by 42.30% (from (33.47±0.95)% to (19.33±1.72)%, P<0.05), and the APS increased markedly from (565.50±31.89) μm to (693.75±16.28) μm (P<0.05). These results indicated that the microencapsulation of IgY was significantly affected by the COS concentration. Hence, the lowest level used herein (0.5%, 5 g/L) was selected as the preliminary optimum COS concentration.

The effects of the IgY/ALG mass ratio on the microencapsulation parameters are presented in Figs. 1g–1i. As revealed in Fig. 1g, the EE was dramatically reduced from (76.04±2.43)% to (35.16±2.32)% (P<0.05) as the IgY/ALG ratio increased from 12.5% to 87.5%. However, the LC was remarkably increased from (8.87±0.28)% to (33.47±0.95)% (P<0.05) as the IgY/ALG ratio improved from 12.5% to 50.0%, but showed a significant reduction (P<0.05) at higher IgY/ALG ratios (Fig. 1h). The maximal EE and LC as well as the minimal APS were obtained at an IgY/ALG level of 50.0% (P<0.05), indicating that this ratio would be another optimum condition for the microencapsulation of IgY.

3.1.2 RSM and model conformation

The EE (response 1), LC (response 2), and APS (response 3) are three important parameters of the microencapsulation quality of IgY. Table 2 shows the response values obtained under different conditions based on the Box-Behnken design (Table 1), and the corresponding predicted values obtained via RSM. The EE of the IgY-loaded microcapsules ranged from (38.83±2.02)% to (79.84±3.59)% (P<0.05), the LC ranged from (12.56±0.28)% to (35.80±1.61)% (P<0.05), and the APS ranged from (543.50±15.26) μm to (684.25±12.04) μm (P<0.05). Furthermore, most of the relative deviations (RD) between observed and fitted values were between −10% and 10%, except for two of the total 51 EE values, suggesting that the models fitted by RSM were appropriate to describe all three response variables.

Table 2.

Experimental design, observed responses, and predicted values of IgY-loaded microcapsules

| Run order | Independent variable | EE (%) |

LC (%) |

APS (μm) |

||||||

| Experimental | Predicted | RD (%) | Experimental | Predicted | RD (%) | Experimental | Predicted | RD (%) | ||

| 1 | A −1 B 1 C 0 | 47.38±3.57f | 46.65 | 1.54 | 22.97±1.73e | 23.71 | −3.22 | 644.00±7.07bc | 630.74 | 2.06 |

| 2 | A 1 B 0 C −1 | 63.83±1.31d | 64.95 | −1.75 | 16.09±0.33h | 17.28 | −7.40 | 632.00±10.13bc | 606.52 | 4.03 |

| 3 | A 0 B 0 C 0 | 78.67±0.77a | 76.78 | 2.40 | 35.28±0.35a | 34.43 | 2.41 | 578.00±38.24g | 574.88 | 0.54 |

| 4 | A 1 B 0 C 1 | 46.33±0.05f | 45.25 | 2.33 | 25.40±0.03d | 24.61 | 3.11 | 627.25±10.47bcd | 606.52 | 3.30 |

| 5 | A 0 B 0 C 0 | 78.89±2.94a | 76.78 | 2.67 | 35.38±1.32a | 34.43 | 2.69 | 589.25±18.10efg | 574.88 | 2.44 |

| 6 | A 0 B 0 C 0 | 73.26±3.26b | 76.78 | −4.80 | 32.85±1.46b | 34.43 | −4.81 | 568.50±45.97gh | 574.88 | −1.12 |

| 7 | A 0 B 0 C 0 | 73.22±0.35b | 76.78 | −4.86 | 32.84±0.16b | 34.43 | −4.84 | 581.00±35.11fg | 574.88 | 1.05 |

| 8 | A 0 B 1 C −1 | 69.52±1.97c | 65.43 | 5.88 | 19.27±0.55g | 17.43 | 9.55 | 684.25±12.04a | 689.95 | −0.83 |

| 9 | A 0 B 1 C 1 | 45.87±1.05f | 45.73 | 0.31 | 32.62±0.74b | 32.75 | −0.40 | 643.00±16.43bc | 634.82 | 1.27 |

| 10 | A 0 B −1 C −1 | 68.81±2.77c | 65.43 | 4.91 | 18.20±0.73g | 18.07 | 0.71 | 586.75±17.95efg | 602.01 | −2.60 |

| 11 | A 1 B −1 C 0 | 61.05±0.51de | 59.45 | 2.62 | 21.17±0.18f | 20.30 | 4.11 | 617.75±17.46cde | 597.93 | 3.21 |

| 12 | A −1 B −1 C 0 | 45.89±2.56f | 46.65 | −1.66 | 21.14±1.18f | 20.30 | 3.97 | 594.75±9.54defg | 597.93 | −0.53 |

| 13 | A −1 B 0 C 1 | 38.83±2.02g | 32.45 | 16.43 | 29.73±1.54c | 28.54 | 4.00 | 616.75±36.40cde | 606.52 | 1.66 |

| 14 | A −1 B 0 C −1 | 45.80±1.00f | 52.15 | −13.86 | 12.56±0.28i | 13.35 | −6.29 | 564.25±13.40gh | 606.52 | −7.49 |

| 15 | A 0 B 0 C 0 | 79.84±3.59a | 76.78 | 3.83 | 35.80±1.61a | 34.43 | 3.83 | 543.50±15.26h | 574.88 | −5.77 |

| 16 | A 1 B 1 C 0 | 57.89±0.57e | 59.45 | −2.69 | 22.74±0.22ef | 23.71 | −4.27 | 615.00±13.11cdef | 630.74 | −2.56 |

| 17 | A 0 B −1 C 1 | 48.13±1.38f | 45.73 | 4.99 | 23.43±0.85e | 25.28 | −7.90 | 655.75±12.26ab | 657.13 | −0.21 |

Relative deviation (RD)=(experimental value–predicted value)/experimental value×100%. Experimental data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=3. Different superscript letters in the same column denote significant differences among experimental responses as affected by different independent variables (P<0.05). In the independent variable column, A means the alginate (ALG) concentration, B represents the chitooligosaccharide (COS) concentration, and C is immunoglobulin Y (IgY)/ALG ratio; different subscript numbers indicate different levels of concentration listed in Table 1. EE: encapsulation efficiency; LC: loading capacity; APS: average particle size

Regression analysis and ANOVA were conducted on the responses (EE, LC, and APS), linear effects (A, B, and C), quadratic effects (A 2, B 2, and C 2), and interactive effects (AB, BC, and AC) to obtain the response surface models and determine their significance (Zimet et al., 2018; He et al., 2019). The results are shown in Table 3, and the equations fitted by RSM with only the statistically significant terms (P<0.05) are expressed as follows:

Table 3.

Regression coefficients and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for response surface models

| Source | Coefficient estimate | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F-value | P-value |

| Response 1: EE (%) | ||||||

| Model | 3290.36 | 5 | 658.07 | 33.23 | <0.0001 | |

| Intercept | 76.78 | |||||

| A | 6.40 | 327.51 | 1 | 327.51 | 16.54 | 0.0019 |

| C | −9.85 | 776.13 | 1 | 776.13 | 39.19 | <0.0001 |

| A² | −15.30 | 986.14 | 1 | 986.14 | 49.79 | <0.0001 |

| B² | −8.42 | 298.65 | 1 | 298.65 | 15.08 | 0.0025 |

| C² | −12.77 | 687.05 | 1 | 687.05 | 34.69 | 0.0001 |

| Residual | 217.85 | 11 | 19.80 | |||

| Lack of fit | 175.41 | 7 | 25.06 | 2.36 | 0.2122 | |

| Pure error | 42.45 | 4 | 10.61 | |||

| Response 2: LC (%) | ||||||

| Model | 856.45 | 7 | 122.35 | 49.12 | <0.0001 | |

| Intercept | 34.43 | |||||

| B | 1.71 | 23.32 | 1 | 23.32 | 9.36 | 0.0136 |

| C | 5.63 | 253.72 | 1 | 253.72 | 101.86 | <0.0001 |

| AC | −1.97 | 15.48 | 1 | 15.48 | 6.21 | 0.0343 |

| BC | 2.03 | 16.47 | 1 | 16.47 | 6.61 | 0.0301 |

| A² | −7.43 | 232.48 | 1 | 232.48 | 93.33 | <0.0001 |

| B² | −4.99 | 104.98 | 1 | 104.98 | 42.14 | 0.0001 |

| C² | −6.05 | 154.27 | 1 | 154.27 | 61.93 | <0.0001 |

| Residual | 22.42 | 9 | 2.49 | |||

| Lack of fit | 13.88 | 5 | 2.78 | 1.30 | 0.4110 | |

| Pure error | 8.54 | 4 | 2.13 | |||

| Response 3: APS (μm) | ||||||

| Model | 16 612.57 | 4 | 4153.14 | 9.21 | 0.0012 | |

| Intercept | 574.88 | |||||

| B | 16.41 | 2153.32 | 1 | 2153.32 | 4.78 | 0.0494 |

| BC | −27.56 | 3038.77 | 1 | 3038.77 | 6.74 | 0.0234 |

| B² | 39.45 | 6572.37 | 1 | 6572.37 | 14.58 | 0.0024 |

| C² | 31.64 | 4227.21 | 1 | 4227.21 | 9.38 | 0.0099 |

| Residual | 5410.04 | 12 | 450.84 | |||

| Lack of fit | 4170.99 | 8 | 521.37 | 1.68 | 0.3230 | |

| Pure error | 1239.05 | 4 | 309.76 | |||

A, B, and C are the ALG concentration (%), chitooligosaccharide (COS) concentration (%), and IgY/ALG ratio (%), respectively. Response 1: R 2=0.9379, adjusted (Adj) R 2=0.9097, predicted (Pred) R 2=0.8189, adequacy of equation (Adeq) precision=16.7657. Response 2: R 2=0.9745, Adj R 2=0.9547, Pred R 2=0.8186, Adeq precision=19.4726. Response 3: R 2=0.7543, Adj R 2=0.6725, Pred R 2 =0.5587, Adeq precision=9.9924. df: degrees of freedom; EE: encapsulation efficiency; LC: loading capacity; APS: average particle size

, ,

|

(10) |

, ,

|

(11) |

. .

|

(12) |

The ANOVA data shown in Table 3 revealed that the model fitting results for all three responses were extremely significant (P<0.01), whereas the lack-of-fit values were not significant (P>0.05). This was in accordance with the RD results (Table 2), indicating that the second-order polynomial models (Eqs. (10)–(12)) could fit the response data of EE, LC, and APS very well. The differential between R 2 and adjusted R 2 can be used to represent the prediction adequacy of equations (Zimet et al., 2018). As shown in Table 3, the model R 2 and adjusted R 2 for EE (Eq. (10)) and LC (Eq. (11)) were both higher than 0.90, with the difference between them being less than 0.30. However, the R 2 and adjusted R 2 for APS (Eq. (12)) were 0.7543 and 0.6725, respectively, with a deviation of about 0.08. These results suggest that the second-order polynomial models had higher prediction accuracy for EE and LC than for APS. The absolute values of coded coefficient estimates (>1) also denote the significance of coefficients, including the intercept, linear, quadratic and interactive coefficients, since coded units allow the comparison of coefficients on a common scale (Marcet et al., 2018). The precision of all the models surpassed 4, demonstrating that the resulting signal-to-noise ratios were extremely low and all the fitting models were good enough to navigate the design space (Zimet et al., 2018).

3.1.3 Estimation of interactive effects and determination of the optimum formulation

The interactive effects of independent variables on EE, LC, and APS were estimated by allowing two of the variables to vary while the other one was fixed. The results are shown as a series of 3D response plots (Fig. 2). As shown in Figs. 2a–2c and Eq. (10), the principal influence on the response EE was attributed to the linear and quadratic effects of the ALG concentration (A), COS concentration (B), and IgY/ALG ratio (C) (P<0.01), rather than their interactions (P>0.05). Specifically, a combination of relatively high ALG concentration (A), low IgY/ALG mass ratio (C), and a COS level (B) trend to 0.60 led to a high EE value. Figs. 2d–2f and Eq. (11) showed that the LC was significantly affected by the linear, quadratic and interactive effects of the ALG concentration (A), COS concentration (B), and IgY/ALG ratio (C) (P<0.05). The highest LC levels were observed when the ALG level (A) was about 1.5%–1.6%, the concentration of COS (B) was near 0.60% and the IgY/ALG ratio (C) was relatively high. However, the APS was determined only by the COS concentration (B), IgY/ALG ratio (C), and their interactive effects (P<0.05; Figs. 2g–2i and Eq. (12)). The smallest APS resulted from a COS concentration (B) under 0.5% combined with an IgY/ALG mass ratio (C) near 50%.

Fig. 2.

Three dimensional (3D) response surface plots showing the interactive effects among ALG concentration (A), COS concentration (B), and IgY/ALG ratio (C) on EE, LC, and APS

(a), (d), and (g) represent the interactive effects between ALG concentration and COS concentration with an IgY/ALG ratio of 50% (mass ratio). (b), (e), and (h) represent the interactive effects between COS concentration and IgY/ALG ratio with an ALG concentration of 1.6% (16 g/L). (c), (f), and (i) represent the interactive effects between IgY/ALG ratio and ALG concentration with a COS concentration of 0.5% (5 g/L). ALG: alginate; COS: chitooligosaccharide; IgY: immunoglobulin Y; EE: encapsulation efficiency; LC: loading capacity; APS: average particle size

As mentioned in Table 1, some constraints were set to optimize the formulation of the microcapsules. Various solutions for the optimum formulation can be obtained using the desirability function method in the Design-Expert software (Jain and Anal, 2016). Using a desirability value of 1, the resulting optimized microcapsule had an ALG concentration of 1.56% (15.6 g/L), a COS concentration of 0.61% (6.1 g/L), and an IgY/ALG ratio of 62.44% (mass ratio). Under these conditions, the predicted EE, LC, and APS were 62.28%, 35.88%, and 590.17 μm, respectively.

3.2. Surface morphology and microstructure

The microstructure and surface morphology of the optimized microcapsules are shown in Fig. 3, with the unprotected IgY and COS-uncoated microcapsules as controls. The unprotected IgY powders had a milky white color, while the IgY-loaded microcapsules were slightly yellow whether COS coated or not (Figs. 3a, 3d, and 3g), suggesting that the application of ALG and/or COS affected the color of the samples. Figs. 3e and 3h show that both COS-coated and uncoated microcapsules had a similar spheroidal and slightly cracked shape with a diameter of about 500–700 μm. However, the COS-coated samples had a smoother and more continuous surface (Fig. 3i), whereas more small cracks (usually 1–5 μm long and less than 0.3 μm wide) were found on the surface of microcapsules not coated with COS (Fig. 3f).

Fig. 3.

Surface morphology and microstructures of IgY-loaded microcapsules optimized by RSM

(a–c), (d–f), and (g–i) represent the unprotected IgY powders, ALG microcapsules containing IgY, and COS-coated ALG microcapsules containing IgY, respectively. (a), (d), and (g) show the appearance of samples; (b), (e), and (h) show the microstructure (30×, observed by SEM) of samples; (c), (f), and (i) show the surface morphology (5000×, observed by SEM) of samples. Microcapsule formulation: ALG concentration, 1.56% (15.6 g/L); COS concentration, 0 or 0.61% (6.1 g/L); IgY/ALG ratio, 62.44% (mass ratio). IgY: immunoglobulin Y; RSM: response surface methodology; SEM: scanning electron microscope; ALG: alginate; COS: chitooligosaccharide

3.3. Microencapsulation parameters and physical properties

The microencapsulation parameters and physical properties of optimized microcapsules are shown in Table 4 in comparison to unprotected IgY powders and COS-uncoated microcapsules. Microcapsules optimized by RSM had an EE of (65.19±2.27)%, LC of (33.75±0.97)%, and APS of (588.75±19.82) μm. These experimental data were similar to the predicted values as shown in Section 3.1, which further confirmed the validity and accuracy of the response models (Eqs. (10)–(12)). The microcapsules coated or uncoated with COS showed no significant differences in microencapsulation parameters (EE, LC, and APS) and physical properties (density, sphericity, and color) (P>0.05). This was in accordance with the microstructure observations as shown in Figs. 3d, 3e, 3g and 3h, and suggested that the COS concentration of 0.61% (6.1 g/L) applied herein for coating was not high enough to affect the microcapsule quality. Furthermore, the microcapsules, whether coated or not with COS, were less red-and yellow-colored (P<0.05), but much darker and blacker (P<0.05) than the unprotected IgY. These results were also in agreement with Figs. 3d and 3g, indicating that both microencapsulation with ALG and coating with COS had significant effects on the color of the samples.

Table 4.

Microencapsulation parameters and physical properties of formulation-optimized microcapsules

| Encapsulation type | EE (%) | LC (%) | APS (μm) | Long-axis length (μm) | Short-axis length (μm) | Sphericity (%) | |

|

| |||||||

| IgY | 151.75±28.93b | ||||||

| ALG+IgY | 67.12±3.39a | 31.12±1.30a | 563.25±12.91a | 614.68±55.57a | 457.08±52.71a | 74.32±4.46a | |

| COS+ALG+IgY | 65.19±2.27a | 33.75±0.97a | 588.75±19.82a | 627.24±42.45a | 487.41±86.66a | 77.41±9.87a | |

|

| |||||||

| Encapsulation type | Average weight (mg) | Density (g/cm3) | Color | ||||

|

| |||||||

| L | a* | b* | W | ||||

|

| |||||||

| IgY | 81.70±0.60a | 3.68±0.86a | 10.68±0.85a | 78.47±0.66a | |||

| ALG+IgY | 0.22±0.02a | 2.36±0.31a | 36.01±3.16b | 1.51±0.34b | 6.05±0.93b | 35.70±3.06b | |

| COS+ALG+IgY | 0.21±0.01a | 2.01±0.16a | 38.36±4.50b | 1.44±0.22b | 6.29±0.40b | 38.02±4.49b | |

COS+ALG+IgY and ALG+IgY represent the optimized IgY-loaded microcapsule coated with and without COS, respectively. Microcapsule formulation: ALG concentration, 1.56% (15.6 g/L); COS concentration, 0 or 0.61% (6.1 g/L); IgY/ALG ratio, 62.44% (mass ratio). Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=3. Different lowercase letters in the same column denote significant differences among diverse samples (P<0.05). IgY: immunoglobulin Y; ALG: alginate; COS: chitooligosaccharide; EE: encapsulation efficiency; LC: loading capacity; APS: average particle size; L: lightness; a*: redness/greenness; b*: yellowness/blueness; W: whiteness

3.4. Simulated GI release of microencapsulated IgY

3.4.1 Release behavior

The optimized microcapsules were digested in vitro under SGD, SID, and SGID conditions. The cumulative releases of IgY from microcapsules under the different simulated digestion conditions are shown in Figs. 4a–4c. The results showed a significantly different IgY release rate during simulated digestion between the COS-coated and uncoated microcapsules. The cumulative releases of IgY from the COS-coated microcapsules after 4 h reached (11.94±0.08)% under SGD and (73.90±1.66)% under SGID, about 6% and 16% lower, respectively, than those released from the COS-uncoated microcapsules under the same conditions (P<0.05). For the microcapsules under SID, most of the microencapsulated IgY (93%–96%, P>0.05) was released after 4 h, whether the samples were COS-coated or not. However, the COS-uncoated sample showed a significantly higher release rate than the coated sample (P<0.05). The microencapsulated IgY showed diverse release behaviors under different digestion conditions. The IgY released much faster in the SID phase than in the SGD phase for both kinds of microcapsules (P<0.05; Figs. 4a–4c). This was considered an advantage for the GI release of IgY, since it needs to be released immediately and perform immune-activity in the intestines rather than in the stomach (Bakhshi et al., 2017).

Fig. 4.

Release behaviors and relative activity of the microencapsulated IgY during simulated digestions

(a), (b), and (c) represent the release behaviors of simulated gastric digestion (SGD), simulated intestinal digestion (SID), and simulated gastrointestinal (GI) digestion (SGID), respectively, and (d) shows the relative activity. Data are expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD), n=3. Different lowercase letters above the error bar denote significant differences among diverse samples as affected by different digestion conditions (P<0.05). COS+ALG+IgY and ALG+IgY represent the optimized IgY-loaded ALG microcapsules coated with and without COS, respectively. Microcapsule formulation: ALG concentration, 1.56% (15.6 g/L); COS concentration, 0 or 0.61% (6.1 g/L); IgY/ALG ratio, 62.44% (mass ratio). IgY: immunoglobulin Y; COS: chitooligosaccharide; ALG: alginate

3.4.2 Kinetics analysis

The release kinetics analysis was performed by fitting the release data of the microcapsules during SGD and SID into different equations (Eqs. (6)–(9)). The results are shown in Table 5. Most of the kinetics models had an R 2 value larger than 0.99, indicating that the IgY release process during SGD or SID was described very well by the fitted models. The zero-order kinetics function had the best fitting precision for microcapsules subjected to SGD (R 2=0.9973 for ALG+IgY and R 2=0.9983 for ALG+IgY+COS), while the first-order kinetics equation was the most suitable model to describe the release behavior during SID (R 2=0.9996 for ALG+IgY and R 2=0.9969 for ALG+ IgY+COS). The COS-coated microcapsules had a lower k0 during SGD as well as a lower k1 and a similar R lim during SID compared with the uncoated samples. This demonstrated that the release of encapsulated IgY was sustained by the COS coating in the GI tract, which agreed with the results as shown in Figs. 4a–4c.

Table 5.

Release kinetics parameters of the microencapsulated IgY during simulated digestion by fitting into different kinetics models

| Encapsulation type | Mathematical model | Digestion condition | Fitted model | R 2 |

| ALG+IgY | Zero-order (Eq. (6)) | SGD | R(t)=13.84t | 0.9973 |

| SID | R(t)=94.31t | 0.8953 | ||

| Higuchi (Eq. (7)) | SGD | R(t)=22.93t 1/2 | 0.9503 | |

| SID | R(t)=168.11t 1/2 | 0.9874 | ||

| Hixson-Crowell (Eq. (8)) | SGD | (311.20−R(t))1/3=6.78−0.11t | 0.9969 | |

| SID | (311.20−R(t))1/3=6.78−1.92t | 0.9944 | ||

| First-order (Eq. (9)) | SGD | R(t)=311.20(1−e − 0.05 t ) | 0.9966 | |

| SID | R(t)=297.70(1−e − 1.15 t ) | 0.9996 | ||

| COS+ALG+IgY | Zero-order (Eq. (6)) | SGD | R(t)=10.35t | 0.9983 |

| SID | R(t)=90.17t | 0.9656 | ||

| Higuchi (Eq. (7)) | SGD | R(t)=17.18t 1/2 | 0.9539 | |

| SID | R(t)=155.30t 1/2 | 0.9942 | ||

| Hixson-Crowell (Eq. (8)) | SGD | (337.49−R(t))1/3 =6.96−0.07t | 0.9982 | |

| SID | (337.49−R(t))1/3 =6.96−1.08t | 0.9969 | ||

| First-order (Eq. (9)) | SGD | R(t)=275.08(1−e − 0.04 t ) | 0.9979 | |

| SID | R(t)=337.49(1−e − 0.57 t ) | 0.9969 |

COS+ALG+IgY and ALG+IgY represent the optimized IgY-loaded ALG microcapsules coated with and without COS, respectively. Microcapsule formulation: ALG concentration, 1.56% (15.6 g/L); COS concentration, 0 or 0.61% (6.1 g/L); IgY/ALG ratio, 62.44% (mass ratio). IgY: immunoglobulin Y; ALG: alginate; COS: chitooligosaccharide; SGD: simulated gastric digestion; SID: simulated intestinal digestion

3.4.3 Changes in immune-activity

The changes in the relative immune-activity of microencapsulated IgY during simulated digestions are illustrated in Fig. 4d. About 96% of the immune-activity of unprotected IgY was lost within 4 h under the combined action of low pH and pepsin enzymolysis (Fig. 4d). After 4 h SGD, the amount of immune-activity preserved was (73.18±4.81)% for the COS-coated and (46.41±5.74)% for the uncoated microcapsules, much higher than that for the unprotected IgY (P<0.05). This suggests that IgY can be effectively protected against SGD by both kinds of microencapsulation and that the protective effect could be significantly enhanced by the COS coating (P<0.05). Although most of the IgY was released from microcapsules after 4 h SID (Fig. 4b), the remaining immuno-activity of IgY microencapsulated with or without COS coating was similar to that of unprotected IgY (87.79%–95.41%, P<0.05; Fig. 4d). This was mainly because the IgY structure was relatively stable under the conditions of pH 4–11 and intestinal proteolysis (Kovacs-Nolan and Mine, 2012; Pereira et al., 2019). Hence, due to the combined effects of SGD and SID, the amount of immune-activity of IgY retained after 4 h SGID was (84.37±4.39)% for the COS-coated and (76.20±3.92)% for the uncoated microcapsules, much higher than that for the unprotected IgY ((5.33±2.37)%, P<0.05).

4. Discussion

The encapsulation parameters of the microcapsules were significantly affected by the ALG concentration, COS concentration, and IgY/ALG ratio (Fig. 1). The EE and LC could be improved by increasing the ALG concentration (Figs. 1a–1c), probably because the loss of encapsulated IgY was reduced by the increased porosity of the microcapsules (Gåserød et al., 1998). However, coating with COS usually led to lower EE and LC and a higher APS (Figs. 1d–1f). Liu et al. (2018) found that the COS coating could significantly reduce the EE and LC as well as increase the size of astaxanthin-β-lactoglobulin nanoparticles, which is in accordance with our results. Moreover, the improved ratio of IgY/ALG would result in an increased LC but a reduced EE, since EE and LC are usually in opposition (Lian et al., 2016).

Although the COS concentration used in the optimized formulation was very low, the microstructure of microcapsules was significantly influenced by the COS coating (Figs. 3d–3f). This can be attributed to the electrostatic interaction-induced self-assembly of the chain-like COS onto the ALG, resulting in the formation of a more stable network on the sample surface (Wang and He, 2010; Chandika et al., 2015). Because of the improvement of surface morphology by COS coating, the release of IgY was sustained (Figs. 4a–4c), the release mechanism of IgY was changed (Table 5), and the preservation of the immune-activity of IgY was enhanced (Fig. 4c). The release of microencapsulated IgY during simulated digestion could be significantly sustained by the COS coating (Figs. 4a–4c). It may be that the electrostatic interactions between –NH3+ of COS and –COO− of ALG allowed the surface to be more stable and less cracked (Figs. 3f and 3i), resulting in a reduction of IgY release (Wang and He, 2010; Chandika et al., 2015). Another reason may be that the bio-adhesive ability of the microcapsules was improved by the COS coating (Gåserød et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2018).

On the other hand, the IgY release during SID from both COS-coated and uncoated microcapsules was higher than that during SGD (Figs. 3f and 3i). The pH-sensitive property of the COS-ALG interactive wall of the microcapsules can partially explain this result. COS-ALG rarely has swelling or water-binding capacity in the acidic gastric environment (pH=1.2), but can swell significantly and bind to water molecules in the neutral intestinal environment (pH=6.8) (Bakhshi et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2017). The disintegration of the electrostatic interaction-induced COS-ALG-Ca2+ network could be another important explanation, since the positive charges from COS would disappear at neutral pH (Bakhshi et al., 2017; Ren et al., 2017). Therefore, different release kinetics were shown for microencapsulated IgY during SGD and SID (Table 5), representing two kinds of release mechanisms. The IgY release was through enzymatic degradation of the microcapsule wall during SGD (Ritger and Peppas, 1987; Eltayeb et al., 2015). However, during SID, it could be attributed to the synergistic effects of IgY diffusion and enzymatic degradation of wall material (Vueba et al., 2004; Mahasukhonthachat et al., 2010). The physical barrier enhanced by COS coating (Figs. 3f and 3i) and the electrostatic interaction between COS and ALG could also be responsible for the immune-activity results (Fig. 4d). This barrier could effectively protect the microencapsulated IgY from exposure to the severe gastric environment, thereby significantly reducing the release of IgY (Fig. 4a) and maintaining its integrity (Wang and He, 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Chandika et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2018).

5. Conclusions

In the present study, ALG microcapsules coated with COS were prepared for the controlled release of IgY in the GI tract. Single-factor results showed that the EE, LC, and APS of the microcapsules were significantly affected by the ALG concentration, COS concentration, and IgY/ALG ratio (P<0.05). The formulation of the IgY-loaded microcapsules was optimized by RSM, and the models showed good fitting accuracies for all response variables (EE, LC, and APS; all P<0.01). The optimum formulation was determined as an ALG level of 1.56% (15.6 g/L), COS level of 0.61% (6.1 g/L), and IgY/ALG ratio of 62.44% (mass ratio). The EE, LC, and APS of formulation-optimized microcapsules were 65.19%, 33.75%, and 588.75 μm, respectively, which agreed satisfactorily with the predictions by RSM (P>0.05). Under the optimized formulation, the coating of COS (0.61%, 6.1 g/L) created a smoother and more continuous microstructure by filling the cracks on the surface, and hence significantly reduced the release rate of microencapsulated IgY during SGID (P<0.05). The IgY release from microcapsules was well described by the zero-order and first-order kinetics functions during SGD and SID, respectively (R 2>0.99). The IgY of COS-coated and uncoated microcapsules retained 84.37% and 76.20% immune-activity after 4 h of SGID, respectively, significantly higher than that for the unprotected IgY (5.33%, P<0.05). The optimized microencapsulation method described in this study could be an efficient way of enabling IgY to tolerate the gastric environment and retain immune-activity in the intestinal tract.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mrs. Chun-jiao SONG and Mrs. Zhen-feng LIAO (Electronic Imaging Laboratory, Public Experimental Platform, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China) for their advice and support on the surface morphology observation of microcapsules.

Footnotes

Project supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFD0400305), the Modern Agro-industry Technology Research System of China (No. CARS-40-K26), and the “One Belt and One Road” International Science and Technology Cooperation Program of Zhejiang, China (No. 2019C04022)

Contributors: Jin ZHANG performed the experimental research and data analysis, wrote and edited the manuscript. Huan-huan LI, Yi-fan CHEN, Yun-xin YAO, and Xu-ming LIU performed the data analysis. Qian LAN and Xiao-fan YU collected and analyzed the data. Li-hong CHEN and Hong-gang TANG contributed to the study design and data analysis. Fan-bin KONG contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and, therefore, have full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and security of the data.

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Jin ZHANG, Huan-huan LI, Yi-fan CHEN, Li-hong CHEN, Hong-gang TANG, Fan-bin KONG, Yun-xin YAO, Xu-ming LIU, Qian LAN, and Xiao-fan YU declare that they have no conflict of interest.

No studies using human or animal subjects were performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Anal AK, Bhopatkar D, Tokura S, et al. Chitosan-alginate multilayer beads for gastric passage and controlled intestinal release of protein. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2003;29(6):713–724. doi: 10.1081/DDC-120021320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakhshi M, Ebrahimi F, Nazarian S, et al. Nano-encapsulation of chicken immunoglobulin (IgY) in sodium alginate nanoparticles: in vitro characterization. Biologicals. 2017;49:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai YC, Guo J, Chen SH, et al. Chicken egg yolk antibodies (IgY) for detecting circulating antigens of Schistosoma japonicum . Parasitol Int. 2012;61(3):385–390. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlander D, Kollberg H, Wejåker PE, et al. Peroral immunotheraphy with yolk antibodies for the prevention and treatment of enteric infections. Immunol Res. 2000;21(1):1–6. doi: 10.1385/ir:21:1:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandika P, Ko SC, Oh GW, et al. Fish collagen/alginate/chitooligosaccharides integrated scaffold for skin tissue regeneration application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;81:504–513. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dávalos-Pantoja L, Ortega-Vinuesa JL, Bastos-González D, et al. A comparative study between the adsorption of IgY and IgG on latex particles. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2000;11(6):657–673. doi: 10.1163/156856200743931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eltayeb M, Stride E, Edirisinghe M. Preparation, characterization and release kinetics of ethylcellulose nanoparticles encapsulating ethylvanillin as a model functional component. J Funct Foods. 2015;14:726–735. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.02.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gandomi H, Abbaszadeh S, Misaghi A, et al. Effect of chitosan-alginate encapsulation with inulin on survival of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG during apple juice storage and under simulated gastrointestinal conditions. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2016;69:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.01.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gåserød O, Smidsrød O, Skjåk-Bræk G. Microcapsules of alginate-chitosan–I: a quantitative study of the interaction between alginate and chitosan. Biomaterials. 1998;19(20):1815–1825. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ha HK, Kim JW, Lee MR, et al. Formation and characterization of quercetin-loaded chitosan oligosaccharide/β-lactoglobulin nanoparticle. Food Res Int. 2013;52(1):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He SD, Zhang Y, Sun HJ, et al. Antioxidative peptides from proteolytic hydrolysates of false abalone (Volutharpa ampullacea perryi): characterization, identification, and molecular docking. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(2):116. doi: 10.3390/md17020116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higuchi T. Mechanism of sustained-action medication. Theoretical analysis of rate of release of solid drugs dispersed in solid matrices. J Pharm Sci. 1963;52(12):1145–1149. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600521210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Igathinathane C, Ulusoy U. Machine vision methods based particle size distribution of ball- and gyro-milled lignite and hard coal. Powder Technol. 2016;297:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2016.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain S, Anal AK. Optimization of extraction of functional protein hydrolysates from chicken egg shell membrane (ESM) by ultrasonic assisted extraction (UAE) and enzymatic hydrolysis. LWT-Food Sci Technol. 2016;69:295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.01.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong C, Kim S, Lee C, et al. Changes in the physical properties of calcium alginate gel beads under a wide range of gelation temperature conditions. Foods. 2020;9(2):180. doi: 10.3390/foods9020180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovacs-Nolan J, Mine Y. Egg yolk antibodies for passive immunity. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2012;3:163–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar Giri T, Thakur D, Alexander A, et al. Alginate based hydrogel as a potential biopolymeric carrier for drug delivery and cell delivery systems: present status and applications. Curr Drug Deliv. 2012;9(6):539–555. doi: 10.2174/156720112803529800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Kang HE, Woo HJ. Stability of orally administered immunoglobulin in the gastrointestinal tract. J Immunol Methods. 2012;384(1-2):143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li XY, Wu MB, Xiao M, et al. Microencapsulated β-carotene preparation using different drying treatments. J Zhejiang Univ-Sci B (Biomed & Biotechnol) 2019;20(11):901–909. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1900157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lian ZR, Pan R, Wang JT. Microencapsulation of norfloxacin in chitosan/chitosan oligosaccharides and its application in shrimp culture. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;92:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.07.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu CZ, Liu ZZ, Sun X, et al. Fabrication and characterization of β-lactoglobulin-based nanocomplexes composed of chitosan oligosaccharides as vehicles for delivery of astaxanthin. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66(26):6717–6726. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b00834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu CH, Engelmann NJ, Lila MA, et al. Optimization of lycopene extraction from tomato cell suspension culture by response surface methodology. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(17):7710–7714. doi: 10.1021/jf801029k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahasukhonthachat K, Sopade PA, Gidley MJ. Kinetics of starch digestion in sorghum as affected by particle size. J Food Eng. 2010;96(1):18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2009.06.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcet I, Salvadores M, Rendueles M, et al. The effect of ultrasound on the alkali extraction of proteins from eggshell membranes. J Sci Food Agric. 2018;98(5):1765–1772. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.8651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mohammadi R, Mohammadifar MA, Mortazavian AM, et al. Extraction optimization of pepsin-soluble collagen from eggshell membrane by response surface methodology (RSM) Food Chem. 2016;190:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.05.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otsuka M, Matsuda Y. Comparative evaluation of mean particle size of bulk drug powder in pharmaceutical preparations by fourier-transformed powder diffuse reflectance infrared spectroscopy and dissolution kinetics. J Pharm Sci. 1996;85(1):112–116. doi: 10.1021/js9500520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauly D, Chacana PA, Calzado EG, et al. IgY technology: extraction of chicken antibodies from egg yolk by polyethylene glycol (PEG) precipitation. J Vis Exp. 2011;(51):e3084. doi: 10.3791/3084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pereira EPV, van Tilburg MF, Florean EOPT, et al. Egg yolk antibodies (IgY) and their applications in human and veterinary health: a review. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;73:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahman S, van Nguyen S, Icatlo FC, Jr, et al. Oral passive IgY-based immunotherapeutics: a novel solution for prevention and treatment of alimentary tract diseases. Hum Vacc Immunother. 2013;9(5):1039–1048. doi: 10.4161/hv.23383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ren ZY, Zhang XR, Guo Y, et al. Preparation and in vitro delivery performance of chitosan–alginate microcapsule for IgG. Food Agric Immunol. 2017;28(1):1–13. doi: 10.1080/09540105.2016.1202206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritger PL, Peppas NA. A simple equation for description of solute release I. Fickian and non-fickian release from non-swellable devices in the form of slabs, spheres, cylinders or discs. J Controlled Release. 1987;5(1):23–36. doi: 10.1016/0168-3659(87)90034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosa-Sibakov N, Sibakov J, Lahtinen P, et al. Wet grinding and microfluidization of wheat bran preparations: improvement of dispersion stability by structural disintegration. J Cereal Sci. 2015;64:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcs.2015.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheraiber M, Grześkowiak Ł, Zentek J, et al. Inclusion of IgY in a dog’s diet has moderate impact on the intestinal microbial fermentation. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;127(4):996–1003. doi: 10.1111/jam.14378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vueba ML, Batista de Carvalho LAE, Veiga F, et al. Influence of cellulose ether polymers on ketoprofen release from hydrophilic matrix tablets. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2004;58(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang T, He N. Preparation, characterization and applications of low-molecular-weight alginate-oligochitosan nanocapsules. Nanoscale. 2010;2(2):230–239. doi: 10.1039/B9NR00125E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang YL, Khan A, Liu YX, et al. Chitosan oligosaccharide-based dual pH responsive nano-micelles for targeted delivery of hydrophobic drugs. Carbohydr Polym, 223: 115061. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei TT, Hishikawa A, Shimizu Y, et al. Particulate characterization of bovine bone granules pulverized with a high-speed blade mill. Powder Technol. 2014;261:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.powtec.2014.04.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xing PP, Shi YN, Dong CC, et al. Colon-targeted delivery of IgY against Clostridium difficile toxin A and B by encapsulation in chitosan-Ca pectinate microbeads. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2017;18(4):1095–1103. doi: 10.1208/s12249-016-0656-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu YF, Lin H, Sui JX, et al. Effects of specific egg yolk antibody (IgY) on the quality and shelf life of refrigerated Paralichthys olivaceus . J Sci Food Agric. 2012;92(6):1267–1272. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Yin T, Xiong SB, et al. Thermal treatments affect breakage kinetics and calcium release of fish bone particles during high-energy wet ball milling. J Food Eng. 2016;183:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.03.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, He SX, Kong FB, et al. Size reduction and calcium release of fish bone particles during nanomilling as affected by bone structure. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017;10(12):2176–2187. doi: 10.1007/s11947-017-1987-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J, Du HY, Zhang GN, et al. Identification and characterization of novel antioxidant peptides from crucian carp (Carassius auratus) cooking juice released in simulated gastrointestinal digestion by UPLC-MS/MS and in silico analysis. J Chromatogr B, 1136:121893. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2019.121893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang YL, Wei W, Lv PP, et al. Preparation and evaluation of alginate-chitosan microspheres for oral delivery of insulin. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;77(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zimet P, Mombrú ÁW, Faccio R, et al. Optimization and characterization of nisin-loaded alginate-chitosan nanoparticles with antimicrobial activity in lean beef. LWT. 2018;91:107–116. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.01.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]