In this Commentary, we address mechanisms of stroke in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) due to infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2). It should be noted that given the recency of the pandemic, most studies are small case series, so this evaluation should be regarded as preliminary.

A review by a panel of the World Stroke Organization reported that the risk of ischemic stroke during COVID-19 is around 5% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.8–8.7%) [1]. COVID-19-related hemorrhagic strokes are far less common than ischemic strokes, but a few cases have been reported [2, 3, 4, 5]. The median time from diagnosis to ischemic stroke in one small single-center study was 10 days (IQR: 1–19) [6]. Patients with COVID-19 who had strokes were more likely to be older and have hypertension and higher levels of D-dimer[1]. Similarly, among 50 patients with ischemic stroke admitted in Wuhan, China, there was more comorbidity, lower platelet counts and leukocyte counts, and the patients had higher levels of D-dimers, cardiac troponin I, NT probrain natriuretic peptide, and interleukin-6 [7]. The strokes are commonly labeled as cryptogenic. In a retrospective review of 32 patients with COVID-19, 65.6% had cryptogenic stroke compared with 30.4% of contemporary controls (p = 0.003) and 25% of historical controls (p < 0.001). The next most frequent stroke category was cardioembolism (22%) [6]. It should be noted that diagnostic investigations could not be completed in some patients with COVID-19 and this might have contributed to the high rate of cryptogenic strokes.

Strokes in patients with COVID-19 may be due to usual causes such as atherosclerosis, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation. In this review, however, we focus on mechanisms of stroke that appear to be directly related to COVID-19. It seems likely that these COVID-19-related mechanisms would also increase the risk of stroke in infected persons who harbor the more conventional stroke risk factors.

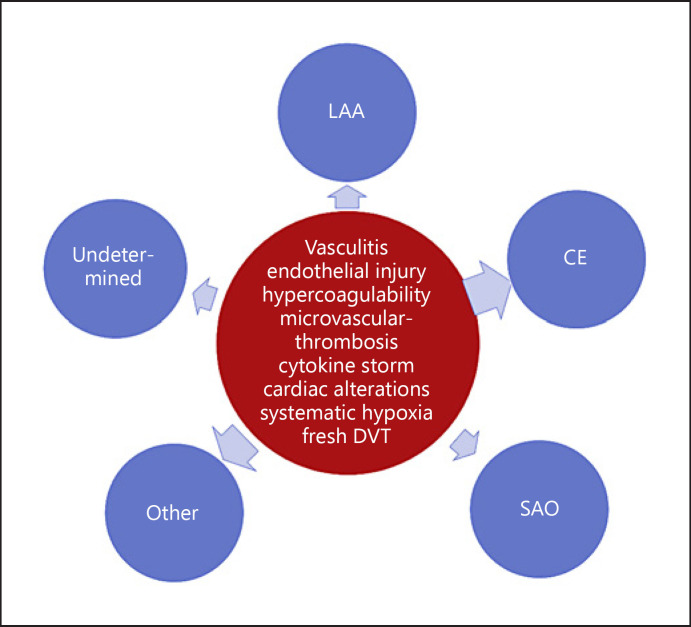

Three main mechanisms appear to be responsible for the occurrence of ischemic strokes in COVID-19 [8, 9] (Fig. 1). These include a hypercoagulable state, vasculitis, and cardiomyopathy. While the pathogenesis of hemorrhagic strokes in the setting of COVID-19 has not been fully elucidated, it is possible that the affinity of the SARS-CoV-2 for ACE2 receptors, which are expressed in endothelial and arterial smooth muscle cells in the brain, allows the virus to damage intracranial arteries, causing vessel wall rupture[10]. In addition, it is possible that the cytokine storm that accompanies this disorder could be the cause of hemorrhagic strokes, as reported in a COVID-19 patient who developed an acute necrotizing encephalopathy associated with late parenchymal brain hemorrhages [4]. This massive release of cytokines may also damage and result in breakdown of the blood-brain barrier and cause hemorrhagic posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES) [11]. Secondary hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic strokes has also been reported in COVID-19 patients [3, 12]. Such transformation may occur in the setting of endothelial damage or a consumption coagulopathy accompanying COVID-19 [12].

Fig. 1.

Potential mechanisms of ischemic stroke in patients with COVID-19. While COVID-19-related systemic and cardiovascular alterations could potentially promote all types of ischemic stroke, the attributable risk is expected to be greater for Other and CE subtypes (larger arrows). LAA, large artery atherosclerosis; CE, cardiac embolism; SAO, small artery occlusion; Other, other uncommon causes of stroke; Undetermined, undetermined causes of stroke; DVT, deep venous thrombosis. It should be noted that in COVID-19, many large artery occlusions may not be due to atherosclerosis but to embolization (from an intracardiac thrombus, or paradoxical emboli from deep vein thrombosis).

Hypercoagulable State

Lee et al. [13] reported that 20–55% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have laboratory evidence of coagulopathy, with increased levels of D-dimer to above twice normal, slight prolongation of prothrombin time (1–3 s above normal), mild thrombocytopenia, and in late disease, decreased fibrinogen levels. A D-dimer level above 4 times normal was associated with a 5-fold increase in the likelihood of critical illness.

Thachil et al. [14] published guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19 from the International Society for Thrombosis and Haemostasis. They recommended monitoring of prothrombin time, D-dimer, platelet count, and fibrinogen and prophylactic anticoagulation with low-molecular weight (LMW) heparin in all patients with COVID-19. Yaghi et al. [6] reported that high levels of D-dimer were more common among patients with stroke and COVID-19 and suggested that hypercoagulability may underly much of stroke in this disease. They indicated that a randomized trial of therapeutic anticoagulation versus prophylactic anticoagulation is underway.

Antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin and anti-β-glycoprotein I antibodies) have been documented in COVID-19 patients with multiple hemispheric infarcts and with concomitant elevation of prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), fibrinogen, D-dimer, and CRP [15]. The lupus anticoagulant was reported to be present in 45% of patients with COVID-19 versus only 10% with anticardiolipin antibody in a study in France (n = 50) [16]. In another study, the lupus anticoagulant was documented in 31 of 34 (91%) COVID-19 patients who had an elevated aPTT, but the frequency of venous thromboembolism was low in this group (2 patients; 6%) [17]. The significance of these findings is unclear as antiphospholipid antibodies were present in subjects with multiple other features of hypercoagulability, and the isolated finding of lupus anticoagulant was not associated with high risk of thromboembolism.

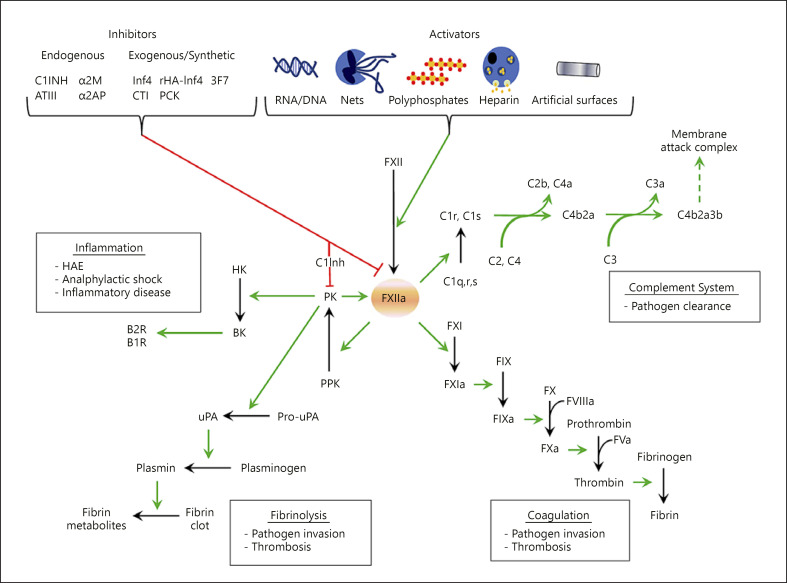

In some patients, the combination of thrombocytopenia, prolonged prothrombin time, increased D-dimer and lactate dehydrogenase levels, and decreased fibrinogen concentrations is consistent with consumption coagulopathy that typically occurs in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Postmortem studies in patients dying of COVID-19 show microvascular platelet-fibrin-rich thrombotic depositions in the lungs as well as in other organs [18, 19, 20]. It has been suggested that viral invasion of the vascular endothelium triggers activation of the contact and complement systems which, in turn, initiates thrombotic and inflammatory cascades leading to internal organ injury [19, 21]. Weidman et al. [22] reviewed the role of inflammation in thrombosis (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The contact system in disease states. FXII is activated into FXIIa either by endogenous activator (nucleic acids RNA/DNA, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), polyphosphate, and heparin) or artificial surfaces. FXIIa then activates 4 different pathways: (1) The inflammation kallikrein-kinin pathway by converting plasma prekallikrein (PPK) into active plasma kallikrein (PK), which cleaves both FXII into FXIIa and high molecular weight kininogen (HK) to bradykinin (BK). The latter binds to kinin receptors (B2 and B1 receptors) and triggers inflammation. (2) The complement system by activation of the C1qrs complex subunits C1r and C1s leading formation of the membrane attack complex by the classical complement pathway. (3) The fibrinolytic system by PK activation of prourokinase into urokinase that in turn cleaves plasminogen into plasmin, an enzyme that degrades fibrin clots. (4) The intrinsic coagulation pathway by FXI activation into FXIa leading to thrombin activation and fibrin generation. The contact system is controlled mainly by C1 inhibitor (C1-Inh) that inhibits both FXIIa and PK. Other endogenous inhibitors including antithrombin III (ATIII), α-2-macroglobulin (α2M), and α-2-antiplasmin (α2AP) contribute in controlling contact system proteases and new synthetic “exogenous” inhibitors have been developed to interfere with contact system-mediated diseases. Green arrows indicate activation, and red arrows inhibition. Protein in bold is the result of proteolytic cleavage of their precursors. Boxed text indicates pathways (underlined) and related disease states (reproduced by permission of Elsevier from: Weidmann H, Heikaus L, Long AT, Naudin C, Schluter H, Renne T. The plasma contact system, a protease cascade at the nexus of inflammation, coagulation and immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2017;1864(11 Pt B):2118–27).

While the relevance of microvascular thrombosis is becoming increasingly clear, a substantial proportion of patients with severe COVID-19 also develop large vessel occlusion. Although in situ thrombosis has been postulated to cause large artery occlusion, this seems unlikely. Red thrombus forms in the setting of stasis; it contains more entrapped red blood cells and less platelets. White thrombus, which forms in the setting of fast flow/high shear rates, contains less entrapped red blood cells and more platelet aggregates [23, 24, 25]. Red thrombus in large arteries probably forms only after a plaque rupture or arterial dissection and in fusiform aneurysms. Many of the patients with large artery occlusion have been younger patients with no vascular risk factors, so unlikely to have large plaques with plaque rupture. Bangalore et al. [26] report that 33% of COVID-19 patients with myocardial infarction did not have obstructive coronary artery disease. At Mt. Sinai Hospital in New York, after thrombectomy, most of the large arteries with occlusive thrombus appeared normal (M. Alberts, personal communication, May 28, 2020). Escalard et al. [27] reported that among 10 patients with stroke and COVID-19, 5 had large artery occlusions in multiple vascular territories. This suggests that large artery occlusion in COVID-19 may be mainly cardioembolic/paradoxical.

In 2 studies, deep venous thrombosis occurred in 20–25% of patients admitted to critical care [28, 29], and in another study this occurred despite prophylaxis with LMW heparin. Klok et al. [30] reported that despite prophylaxis with LMW heparin, 31% of the 100 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia admitted to the ICU had an arterial (3.7%) or venous (96.3%) thrombotic manifestation; all arterial events were strokes, and 81% of all thrombotic events were pulmonary emboli. They suggested that prophylaxis should be implemented with higher than usual doses of LMW heparin. In a recent autopsy study of 12 cases from Germany, fresh thrombus in the deep venous system was detected in 7; in addition, there was a fresh thrombus in the prostatic venous plexus in 6 cases [31]. In a French study, 79% of 34 patients admitted to the ICU had DVT at 48 h after admission [32]. These findings suggest that paradoxical embolism could be a plausible mechanism of stroke in some patients with COVID-19 coagulopathy. Indeed, paradoxical embolism may account for some or many of the large artery ischemic strokes in young people, including extracranial occlusion of the common and internal carotid artery [33].

Vasculitis

SARS-CoV-2 causes clinical COVID-19 by its affinity for the ACE2 receptors that are expressed in the lungs, heart, kidneys, and small bowel. These receptors are also abundant in the vascular endothelium [34], where infection elicits an inflammatory response (a lymphocytic “endotheliitis”) [18] that has been postulated as one of the substrates for the thrombotic complications of this infection. In a recent pathological study in patients with COVID-19 infection (2 autopsies and 1 surgical biopsy), Varga et al. [18] documented viral inclusions in endothelial cells in the kidneys, heart, lungs, and small bowel, with associated widespread endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis. The authors speculated that a virus-induced state of systemic impaired microcirculatory function in different vascular beds may form the basis for the multiorgan failure that characterizes the severe cases of COVID-19. Vessels may not only be inflamed by a direct local effect of SARS-CoV-2 on the ACE2 receptors in the vascular endothelium but also by a systemic immune response to the pathogen (“cytokine storm”). In the case of COVID-19, several cytokines, including IL1B, IFNγ, IP10, and MCP1 have been found to be markedly elevated, especially in patients with severe disease and high rates of mortality [35].

Ackermann et al. [36] reported an autopsy series of 7 cases of COVID-19 compared with 7 cases of influenza. They noted that distinctive pulmonary features in COVID-19 included diffuse alveolar damage with perivascular T-cell infiltration, severe endothelial injury associated with the presence of intracellular virus and disrupted cell membranes, widespread thrombosis with microangiopathy, and angiogenesis [36].

The role that these various vascular and immune-mediated factors play in the pathogenesis of stroke in COVID-19 patient remains unclear. More data are needed regarding angiographic and postmortem studies of the cervical-cerebral vasculature in order to evaluate the presence and magnitude of vasculitis and its potential role in in-situ clot formation as a potential mechanism of ischemic stroke. It seems unlikely that angiography will disclose an endotheliitis, although it may show large vessel occlusion. The large vessel occlusions are also in atypical locations, such as extensive thrombus emanating from the common carotid artery. Whether such large artery thrombi form at the site, or are embolic, remains to be determined. As discussed above and below, it seems likely that some or many of the large artery occlusions may be embolic.

The clinical stroke observations have included instances in which predominantly large-vessel territorial infarcts have occurred in subjects with conventional risk factors (age, hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and ischemic heart disease) who were infected by SARS-CoV-2 and had high levels of inflammatory markers (such as CRP and ferritin) and markers of coagulation and fibrinolysis (such as D-dimer, fibrinogen, and lupus anticoagulant) [9]. The vascular images provided were indicative of large vessel occlusion without features to suggest an alternative mechanism such as multifocal or widespread vascular wall inflammation (vasculitis). A recent report from Italy compared stroke patients with (n = 43) and without (n = 68) COVID-19. Baseline characteristics including age, sex, and vascular risk factors were similar between the 2 groups [37]. Hemorrhagic strokes were less common in COVID-19 patients (7.0 vs. 13.4%). However, initial stroke severity, measured by the NIHSS, was greater in COVID-19 than in non-COVID-19 patients (10 vs. 4), suggesting involvement of large vessels. Unfortunately, neither vessel images nor stroke subtype classification were reported. Other small series have confirmed cases of large vessel vascular occlusion, and some authors have stressed a high frequency of stroke in young COVID-19 subjects (ages 33–49) with a low prevalence of conventional stroke risk factors and elevated markers of inflammation (ferritin) and coagulation (D-dimer and fibrinogen) [8]. The high frequency of ischemic stroke in young subjects with COVID-19 and a paucity of vascular risk factors raises the possibility that mechanisms peculiar to COVID-19 may be responsible. These could include abnormalities in the vascular endothelium related to direct viral invasion and inflammation (“endotheliitis”), along with the results of a “cytokine storm” (commonly observed in this patient group).

A virus-induced prothrombotic state may play an additional role, potentially synergistic, in the pathogenesis of ischemic strokes of all types in COVID-19 patients. An additional prothrombotic factor is impaired endothelial expression of heparan sulfate, which promotes thrombosis [37]. It is clear that more data in this area are required in order to establish more precisely the potential contribution of these various processes in the pathogenesis of stroke in COVID-19 patients.

Cardiomyopathy

There are a number of mechanisms for cardiac involvement in COVID-19 patients [38, 39, 40]. There may be direct invasion by the virus, causing a myocarditis, with resultant injury and even death of cardiomyocytes. This may due to the affinity of the virus for ACE2, a membrane-bound aminopeptidase, which acts as a portal of viral entry, and downregulation of ACE2, leading to myocardial dysfunction [36]. The heart may also be indirectly affected by the systemic inflammatory state during the severe phase of the infection related to the cytokine storm where many “bystander” end-organs are damaged [40].

There is also increased cardiac stress due to respiratory failure and hypoxemia from the infection, leading to stress cardiomyopathy. An additional possible mechanism for cardiac damage in COVID-19 is stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system, predisposing to stress cardiomyopathy and cardiac arrhythmias [41, 42]. These may lead to arrhythmias and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. The consequent intracardiac thrombus formation, possibly compounded by the hypercoagulable states, raises the risk of subsequent cardioembolic stroke. Some of the published case series of stroke during COVID-19 have not evaluated cardioembolic mechanisms [8, 9].

An early report from China and the previous report from Singapore on SARS-CoV-1 infection developing stroke during that 2002–2003 outbreak demonstrated cardioembolic mechanisms in 36 and 60% of their cases, respectively [43]. Yaghi et al. [6] reported that stroke patients with COVID-19 were more likely to be young men with elevated troponin levels compared with historical controls.

Implications for Therapy

Anticoagulation

All patients admitted to intensive care should receive prophylaxis against venous thrombosis, with at least LMW heparin [14]. In patients with stroke, a cardioembolic mechanism should be strongly suspected, and if there are findings to support that suspicion, such as infarction in multiple cerebral vascular territories (or systemic and cerebral emboli), cardiomyopathy with significant ventricular dyskinesia, atrial fibrillation, or right-to-left shunt, the patient should probably receive therapeutic doses of anticoagulation [44].

A theoretical consideration, based on the experience of Klok et al. [30], is that perhaps DOACs (which target only one clotting factor) might be less effective than heparin or warfarin, which target multiple clotting factors [45, 46]. Warfarin interferes with the synthesis of factors II, VII, IX, and X [47]. Atarashi et al. [46] suggested that the reason warfarin causes more intracerebral hemorrhage is that it targets factor VII. It seems likely that interference with multiple clotting factors may be why warfarin is more effective than DOACs in patients with mechanical heart valves [48, 49, 50].

Tang et al. [51] reported that anticoagulation reduced mortality in COVID-19 patients with coagulopathy. In reply, Asakura and Ogawa [52] noted that some features of the coagulopathy in COVID-19 suggest DIC and recommended a combination of heparin and nafamostat mesylate, a treatment used for DIC in Japan. Thachil et al. [53] responded with a discussion of possible benefits of unfractionated heparin versus LMW heparin.

Besides anticoagulation, there may be reason to consider thrombolytic therapy. Wang et al. [54] suggested from a small case series that tissue plasminogen activator may be beneficial in acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-10.

Anti-Inflammatory Therapies

Based on their benefit as anti-inflammatory agents in cardiovascular clinical trials, therapies such as IL-6R monoclonal antibodies (tocilizumab), TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept and infliximab), and IL-1β antagonists (the monoclonal antibody canakinumab and the anti-cytokine anakinra) have been suggested as potentially beneficial for COVID-19 patients [55]. However, the main concern related to the use of immunosuppression, including corticosteroids, is that it may delay the elimination of the virus [56] and increase the risk of secondary infection, especially in those with an impaired immune system [57].

Though there is no evidence from randomized controlled trials, anti-inflammatory agents, including corticosteroids, are empirically used for severe complications in patients with COVID-19, such as ARDS, and acute cardiac and renal involvement [58]. Whether systemic corticosteroids or other anti-inflammatory agents can be of value in the selected cases of stroke in which vasculitis is suspected is a matter of debate. Neurologists should carefully balance the risk and benefit ratio before starting anti-inflammatory therapies.

Antiviral Therapy

Beigel et al. [59] reported that in a randomized controlled trial in 1,059 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, remdesivir was associated with a shorter median recovery time (11 days, 95% CI: 9–12), compared with placebo (15 days, 95% CI: 13–19), and a lower 14-day mortality of 7.1% with remdesivir versus 11.9% with placebo (hazard ratio for death, 0.70; 95% CI: 0.47–1.04). Stroke was not mentioned in the report.

Future Research

The list of clinical trials registered at ClinicalTrials.gov can be found at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond = COVID-19. Important therapeutic targets in these trials include virus neutralization, prevention and treatment of thrombotic complications, and inhibition of the cytokine storm. Such trials test a wide range of therapies from convalescent and hyperimmune plasma for virus neutralization to tissue plasminogen activator for treatment of microvascular thrombosis and from hemodialysis with reconditioning of immune cells to complement inhibitors, selective cytokine inhibitors, and colchicine to prevent the cytokine storm, based on a study on coronary artery disease [60].

Conclusions

A number of mechanisms are involved in stroke in COVID-19, including a hypercoagulable state, DIC, necrotizing encephalopathy, vasculitis, and cardiomyopathy. It seems likely that anticoagulation will play a substantial role in the management of stroke in COVID-19. Further evidence is needed from larger studies.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Ay is employed by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; none of the other authors has a disclosure that is relevant to this topic.

Author Contributions

J.D.S. wrote the first and final draft; each of the other authors contributed to revisions.

References

- 1.Qureshi AI, Abd-Allah F, Al-Senani F, Aytac E, Borhani-Haghighi A, Ciccone A, et al. Management of acute ischemic stroke in patients with COVID-19 infection: report of an international panel. Int J Stroke. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1747493020923234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Saiegh F, Ghosh R, Leibold A, Avery MB, Schmidt RF, Theofanis T, et al. Status of SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID-19 and stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muhammad S, Petridis A, Cornelius JF, Hanggi D. Letter to editor: severe brain haemorrhage and concomitant COVID-19 infection: a neurovascular complication of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:150–1. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poyiadji N, Shahin G, Noujaim D, Stone M, Patel S, Griffith B. COVID-19-associated acute hemorrhagic necrotizing encephalopathy: CT and MRI features. Radiology. 2020:201187. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020201187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharifi-Razavi A, Karimi N, Rouhani N. COVID-19 and intracerebral haemorrhage: causative or coincidental? New Microbes New Infect. 2020;35:100669. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaghi S, Ishida K, Torres J, Grory BM, Raz E, Humbert K, et al. SARS2-CoV-2 and stroke in a New York healthcare system. Stroke. 2020;51((7)):2002–11. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin C, Zhou L, Hu Z, Yang S, Zhang S, Chen M, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with a history of stroke in Wuhan, China. Stroke. 2020;51((7)):2219–23. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oxley TJ, Mocco J, Majidi S, Kellner CP, Shoirah H, Singh IP, et al. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of COVID-19 in the young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382((20)):e60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyrouti R, Adams ME, Benjamin L, Cohen H, Farmer SF, Goh YY, et al. Characteristics of ischaemic stroke associated with COVID-19. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020 doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-323586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carod-Artal FJ. Neurological complications of coronavirus and COVID-19. Rev Neurol. 2020;70((9)):311–22. doi: 10.33588/rn.7009.2020179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franceschi AM, Ahmed O, Giliberto L, Castillo M. Hemorrhagic posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome as a manifestation of COVID-19 infection. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2020 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valderrama EV, Humbert K, Lord A, Frontera J, Yaghi S. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection and ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2020;51((7)):e127–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SG, Fralick M, Sholzberg M. Coagulopathy associated with COVID-19. CMAJ. 2020;192((21)):E583. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Cattaneo M, Levi M, et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18((5)):1023–6. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Xiao M, Zhang S, Xia P, Cao W, Jiang W, et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382((17)):e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harzallah I, Debliquis A, Drenou B. Lupus anticoagulant is frequent in patients with covid-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowles L, Platton S, Yartey N, Dave M, Lee K, Hart DP, et al. Lupus anticoagulant and abnormal coagulation tests in patients with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395((10234)):1417–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magro C, Mulvey JJ, Berlin D, Nuovo G, Salvatore S, Harp J, et al. Complement associated microvascular injury and thrombosis in the pathogenesis of severe COVID-19 infection: a report of five cases. Transl Res. 2020;220:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2020.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lax SF, Skok K, Zechner P, Kessler HH, Kaufmann N, Koelblinger C, et al. Pulmonary arterial thrombosis in COVID-19 with fatal outcome: results from a prospective, single-center, clinicopathologic case series. Ann Intern Med. 2020:M20–2566. doi: 10.7326/M20-2566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maglakelidze N, Manto KM, Craig TJ. A review: does complement or the contact system have a role in protection or pathogenesis of COVID-19? Pulm Ther. 2020:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s41030-020-00118-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weidmann H, Heikaus L, Long AT, Naudin C, Schlüter H, Renné T. The plasma contact system, a protease cascade at the nexus of inflammation, coagulation and immunity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1864((11 Pt B)):2118–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirsh J, Raschke R, Warkentin TE, Dalen JE, Deykin D, Poller L. Heparin: mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing considerations, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 1995;108((4 Suppl)):258S–75S. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.4_supplement.258s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Caplan LR, Fisher M. The endothelium, platelets, and brain ischemia. Rev Neurol Dis. 2007;4((3)):113–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chernysh IN, Nagaswami C, Kosolapova S, Peshkova AD, Cuker A, Cines DB, et al. The distinctive structure and composition of arterial and venous thrombi and pulmonary emboli. Sci Rep. 2020;10((1)):5112. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59526-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bangalore S, Sharma A, Slotwiner A, Yatskar L, Harari R, Shah B, et al. ST-segment elevation in patients with Covid-19: a case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382((25)):2478–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Escalard S, Maier B, Redjem H, Delvoye F, Hebert S, Smajda S, et al. Treatment of acute ischemic stroke due to large vessel occlusion with COVID-19: experience from Paris. Stroke. 2020 doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Middeldorp S, Coppens M, van Haaps TF, Foppen M, Vlaar AP, Muller MCA, et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18((6)):1421–4. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klok FA, Kruip MJHA, van der Meer NJM, Arbous MS, Gommers DAMPJ, Kant KM, et al. Thrombosis research. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wichmann D, Sperhake JP, Lutgehetmann M, Steurer S, Edler C, Heinemann A, et al. Autopsy findings and venous thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020:M20–2003. doi: 10.7326/M20-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nahum J, Morichau-Beauchant T, Daviaud F, Echegut P, Fichet J, Maillet JM, et al. Venous thrombosis among critically Ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3((5)):e2010478. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.10478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutchinson EC, Acheson EJ. Strokes: natural history, pathology and surgical treatment. In: on J, editor. Saunders. Philadelphia W.B: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203((2)):631–7. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395((10223)):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in covid-19. New Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nugent MA, Nugent HM, Iozzo RV, Sanchack K, Edelman ER. Perlecan is required to inhibit thrombosis after deep vascular injury and contributes to endothelial cell-mediated inhibition of intimal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97((12)):6722–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akhmerov A, Marbán E. COVID-19 and the heart. Circ Res. 2020;126((10)):1443–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adão R, Guzik TJ. Inside the heart of COVID-19. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116((6)):e59–61. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng R, Leedy D. COVID-19 and acute myocardial injury: the heart of the matter or an innocent bystander? Heart. 2020 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2020-317025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clerkin KJ, Fried JA, Raikhelkar J, Sayer G, Griffin JM, Masoumi A, et al. COVID-19 and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2020;141((20)):1648–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.046941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Venketasubramanian N, Hennerici MG. Stroke in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Cererbrovascular Dis Forthcoming. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spence JD. Anticoagulation in patients with embolic stroke of unknown source. Int J Stroke. 2019;14((4)):334–6. doi: 10.1177/1747493019826363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hirsh J, Warkentin TE, Shaughnessy SG, Anand SS, Halperin JL, Raschke R, et al. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin: mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 2001;119((1 Suppl)):64S–94S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.64s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Atarashi H, Inoue H, Okumura K, Yamashita T, Kumagai N, Origasa H, et al. Present status of anticoagulation treatment in Japanese patients with atrial fibrillation: a report from the J-RHYTHM Registry. Circ J. 2011;75((6)):1328–33. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peterson CE, Kwaan HC. Current concepts of warfarin therapy. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146((3)):581–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, Granger CB, Kappetein AP, Mack MJ, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 2013;369((13)):1206–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jaffer IH, Stafford AR, Fredenburgh JC, Whitlock RP, Chan NC, Weitz JI. Dabigatran is less effective than warfarin at attenuating mechanical heart valve-induced thrombin generation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4((8)):e002322. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaffer IH, Fredenburgh JC, Stafford A, Whitlock RP, Weitz JI. Rivaroxaban and dabigatran for suppression of mechanical heart valve-induced thrombin generation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.10.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang N, Bai H, Chen X, Gong J, Li D, Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18((5)):1094–9. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asakura H, Ogawa H. Potential of heparin and nafamostat combination therapy for COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18((6)):1521–2. doi: 10.1111/jth.14858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thachil J, Tang N, Gando S, Falanga A, Levi M, Clark C, et al. Type and dose of heparin in covid-19: reply. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang J, Hajizadeh N, Moore EE, McIntyre RC, Moore PK, Veress LA, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) treatment for COVID-19 associated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): a case series. J Thromb Haemost. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jth.14828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang L, Zhang Y, Zhang S. Cardiovascular Impairment in COVID-19: learning from current options for cardiovascular anti-inflammatory therapy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7((78)):78. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2020.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wong SS, Yuen KY. The management of coronavirus infections with particular reference to SARS. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62((3)):437–41. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang W, Zhao Y, Zhang F, Wang Q, Li T, Liu Z, et al. The use of anti-inflammatory drugs in the treatment of people with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): the perspectives of clinical immunologists from China. Clin Immunol. 2020;214:108393. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Intensive Care Med. 2020;46((5)):854–87. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beigel JH, Tomashek KM, Dodd LE, Mehta AK, Zingman BS, Kalil AC, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of covid-19: preliminary report. New Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2022236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381((26)):2497–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]