To the Editor

Serology is an important pillar in the diagnostics of SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially when PCR may no longer be positive. We thus read with interest the recent report by Tré-Hardy et al.1 on SARS-CoV-2 serology three weeks into COVID-19. With new data from a longitudinal cohort study, we here complement this knowledge by following patients up to 10 weeks after proven SARS-CoV-2 infection. The obtained serological measurements suggested rapidly declining levels of IgG antibodies against the virus spike (SP) and nucleocapsid (NC) proteins as well as strong gender-specific characteristics of both IgG and IgA antibody levels against the virus SP. We focus on IgG and IgA as IgM antibodies seem inconsistent and not occurring earlier than the IgG response.2 A decline in an antibody titer we observe here has impact on the interpretation of serological results obtained at specific time points, specifically when used for disease surveillance.

This cohort study included patients with a history of a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test. The study is registered in the COVID-19 database (https://swissethics.ch/covid-19/approved-projects) and approved by the regional ethics committee (ID2020–00941). Potential participants were identified in the public health database and voluntary participation was based on the informed consent and documented positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR. After inclusion in the study, antibody tests were performed every week in the first month and then after another four weeks in the second month. Quantitative (optical index, OI) antibody measurements were performed using commercially available3 , 4 ELISA assays (anti-SP IgG and IgA, Euroimmun, Lübeck, Germany; anti-NC IgG, Epitope Diagnostics, San Diego, USA) according to the recommendations of the manufacturers. Data were evaluated and visualized with the statistical software R using the implemented statistical tests and the packages “tidyverse” and “ggplot2”.

Results of the antibody course in 159 participants (52•2% females, 47•8% males), effectively spanning the time frame of two to ten weeks after a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test, are provided. Upon the first blood sampling (corresponding to the median of 5 weeks after the PCR test (95% CI 5–6 weeks)), 4•6%, 4•6% and 6•5% of participants have not developed measurable anti-SP IgG, anti-SP IgA or anti-NC IgG, respectively. This may suggest a delayed or missing primary humoral response in a sizeable proportion of patients (at a time when any IgM response is believed to have worn off2). We speculate this to be secondary to a suspected virus’ ability to modify or suppress innate immune responses.5

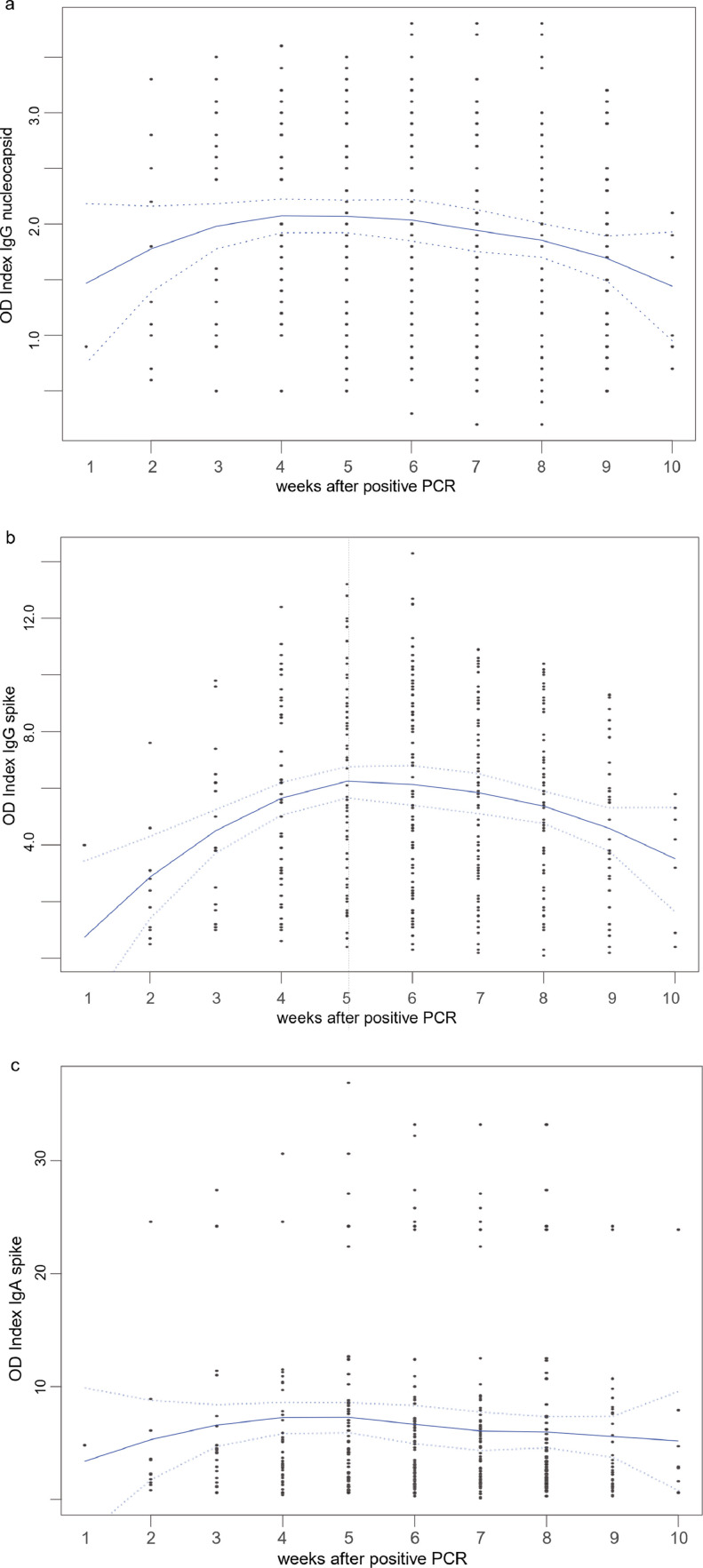

After a significant increase, we find the antibody response to peak 4–5 weeks after positive PCR, followed by an early decline. The decline is statistically significant for anti-SP and anti-NC IgG at weeks 8–10 (Fig. 1 ); this is remarkable, as a continued IgG response for more than 34 weeks was seen with the SARS-CoV(−1) outbreak.6

Fig. 1.

a-c: Overall (gender independent) course of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: a) anti-NC IgG; b) anti-SP IgG; c) anti-SP IgA. Local Polynomial Regression Fitting with 2 standard errors (dotted lines). Anti-NC IgG showed a significant increase (weeks 3 to 5) before a significant decline (weeks 8 to 10, all p < 0•0075, Wilcoxon test, 1a), as did anti-SP IgG (weeks 4 to 6 and weeks 8 to 10, all p< 0•012, 1b). Note the dichotomous IgA distribution, 1c.

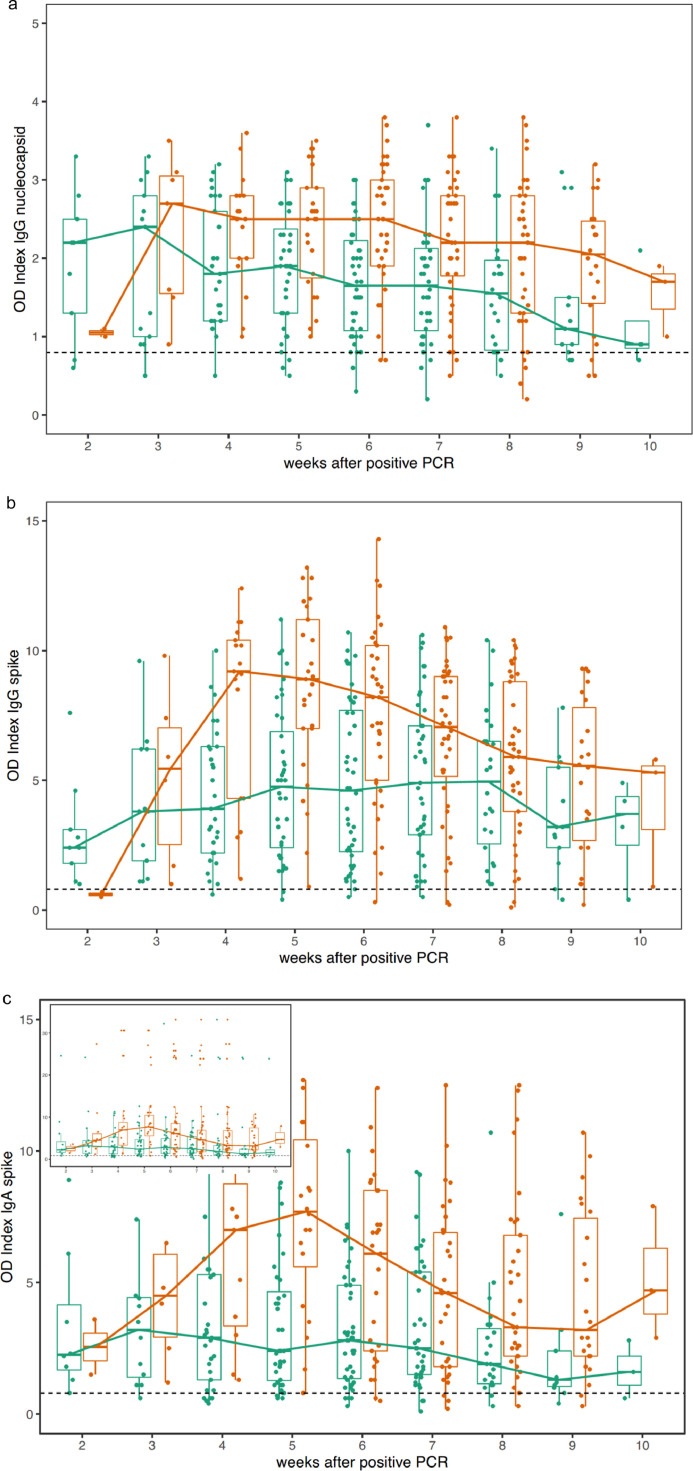

Moreover, significantly higher antibody concentrations are seen in men for all antibodies (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

a-c: Sex specific course of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in females (green) and males (red): a) anti-NC IgG; b) anti-SP IgG; c) anti-SP IgA. Curves connect medians. Significant differences are seen weeks 6 - 7 (anti-NC IgG, all p<0•0054, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 2a); weeks 4 - 5 (anti-SP IgG, all p < 0•0004, Fig. 2b); and weeks 4 - 7 (anti-SP IgA, all p < 0•0095, Fig. 2c). Samples from predominantly male (77% of samples with OI > 20, p < 0•01, Fisher's exact test) patients with very high, dichotomically separated IgA antibody values were seen (inset 2c, see also 1c). Dotted lines separate increased (reactive) from non-increased antibody concentrations.

In addition, anti-SP IgA antibody concentrations showed a striking dichotomy in the distribution of their values among the patients (Figs. 1c and 2c). A subgroup of individuals with extremely high values had a significantly higher fraction of men than the rest of the cohort (77% of samples with OD > 20, p < 0•01). This observation might help to explain the higher mortality risk in men with COVID compared to women,7 e.g. through an increased inflammatory response.8 We speculate that the overall course of anti-SP IgA (with no further decline despite IgG declining, Fig. 1c) as well as the sex specific differences with an early, pronounced peak in men and a subpopulation of men with significantly higher IgA titers than the remainder (Fig. 2c) may be the result of an ongoing infection, which needs further attention and clarification (previous work has shown that IgA has a protective role against influenza A9). Whether this represents a spike-“antibody dependent infection enhancement” in COVID-19, as suggested for SARS-CoV(−1),10 remains to be elucidated.

In summary, according to the antibody kinetics observed here, interpretation of antibody results should be undertaken with knowledge of the time that has elapsed since the infection/positive PCR, as interpretation without this knowledge might be misleading (the early presence of specific (IgG/IgA) antibodies is not necessarily associated with their presence later on). After SARS-CoV-2 infection, the immune system seems to produce different amounts of IgG and IgA in women and men (Fig. 2), possibly helping to explain the higher risk of adverse COVID outcome in men through a stronger (inflammatory) response. If confirmed on other cohorts, these observations should be considered when assessing the efficacy and safety of novel vaccine candidates against SARS-CoV-2.

Funding came from the Center for Laboratory Medicine, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology St. Gallen (Empa) and the Canton of St. Gallen.

References

- 1.Tre-Hardy M., Blairon L., Wilmet A. The role of serology for COVID-19 control: population, kinetics and test performance do matter. J Infect. 2020;81(2):e91–ee2. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qu J., Wu C., Li X. Profile of IgG and IgM antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beavis K.G., Matushek S.M., Abeleda A.P.F. Evaluation of the EUROIMMUN Anti-SARS-CoV-2 ELISA Assay for detection of IgA and IgG antibodies. J Clin Virol. 2020;129 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Theel E.S., Harring J., Hilgart H., Granger D. Performance Characteristics of four high-throughput immunoassays for detection of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JCM.01243-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kikkert M. Innate immune evasion by human respiratory RNA viruses. J Innate Immun. 2020;12(1):4–20. doi: 10.1159/000503030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woo P.C., Lau S.K., Wong B.H. Longitudinal profile of immunoglobulin G (IgG), IgM, and IgA antibodies against the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus nucleocapsid protein in patients with pneumonia due to the SARS coronavirus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(4):665–668. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.4.665-668.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parohan M., Yaghoubi S., Seraji A., Javanbakht M.H., Sarraf P., Djalali M. Risk factors for mortality in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging Male. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1080/13685538.2020.1774748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu W.J., Cao J., Yu L., Hu X., Liu Q. Clinicolaboratory study of 25 fatal cases of COVID-19 in Wuhan. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1117–1120. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould V.M.W., Francis J.N., Anderson K.J., Georges B., Cope A.V., Tregoning J.S. Nasal IgA Provides Protection against Human Influenza Challenge in Volunteers with Low Serum Influenza Antibody Titre. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:900. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaume M., Yip M.S., Cheung C.Y. Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike antibodies trigger infection of human immune cells via a pH- and cysteine protease-independent FcgammaR pathway. J Virol. 2011;85(20):10582–10597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00671-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]