Highlights

-

•

A novel healthcare waste location-routing problem is developed with a new perspective in healthcare logistics networks.

-

•

A stochastic essence for the emission of contamination is considered.

-

•

The management of medical wastes in Coronavirus Disease 2019 is focused.

-

•

A real case study is modeled to manage the logistics of infectious and non-infectious healthcare wastes.

-

•

A Multi-Objective Water-Flow like Algorithm with novel operators is developed and compared with the others.

Keywords: Waste management, Healthcare wastes, Location-routing problem, Logistic network, Water-flow like algorithm, MADM

Abstract

This paper presents a novel healthcare waste location-routing problem by concentrating on a new perspective in healthcare logistics networks. In this problem, there are healthcare, treatment, and disposal centers. Locations of healthcare centers are known, however, it is required to select appropriate locations for treatment, recycling, and disposal centers. Healthcare wastes are divided into infectious and non-infectious wastes. Since a great volume of healthcare wastes are infectious, the emission of contamination can have obnoxious impacts on the environment. The proposed problem considers a stochastic essence for the emission of contamination which depends on the transferring times. In this respect, transferring times between healthcare and treatment centers have been considered as normal random variables. As transferring time increases, it is more likely for the contamination to spread. Having visited a treatment center, infectious wastes are sterilized and they will no longer be harmful to the environment. This research develops a bi-objective mixed-integer mathematical formulation to tackle this problem. The objectives of this model are minimization of total costs and emission of contamination, simultaneously. Complexity of the proposed problem led the researchers to another contribution. This study also develops a Multi-Objective Water-Flow like Algorithm (MOWFA), which is a meta-heuristic, to solve the problem. This algorithm uses a procedure based on the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) to rank the non-dominated solutions in the archive set. By means of a developed mating operator, the MOWFA utilizes the best ranked solutions of the archive in order to obtain high quality offspring. Two neighborhood operators have been designed for the MOWFA as the local search methods. Extensive computational experiments have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the MOWFA on several test problems compared with other meta-heuristics, namely the Multi-Objective Imperialist Competitive Algorithm (MOICA) and Multi-Objective Simulated Annealing (MOSA). These experiments also include a real healthcare waste logistic network in Iran. The computational experiments demonstrate that our proposed algorithm prevails these algorithms in terms of some well-known performance evaluation measures.

1. Introduction

Industrialization and population growth have led the world to rapid increase of waste generation (Dehghani et al., 2019). Among different types of wastes, managing healthcare wastes has always been a crucial environmental concern for human beings. In developing countries, healthcare waste generation is increasing rapidly since the access to medical services has been improved, and therefore more individuals go to healthcare centers to undergo medical procedures (Windfeld and Brooks, 2015). The amount of medical wastes generated in each country depends on its medical situations. Lee et al. (2004) summarized the generation rate of medical wastes in different countries. Inappropriate handling of healthcare wastes can be a threat to public health (Alagöz and Kocasoy, 2008). For providing healthcare services to the growing population, the number of healthcare institutions has been increased in the whole world. As the number of healthcare centers increases, the amount of healthcare wastes grows remarkably. However, if the healthcare wastes are not tackled properly, it may have detrimental effects on the environment. Healthcare wastes are produced because of medical treatment, scientific experiments, and health protection. These wastes can be categorized into infectious and non-infectious wastes. Infectious wastes are defined as hazardous materials that are suspected of having pathogens in sufficient amounts to impose disease on susceptible preys. Living organisms are affected and diseased by the toxins of these viable microorganisms. Parasites, bacteria, viruses, and fungi are examples of pathogens. The following materials are considered as infectious wastes: (1) infectious materials used in autopsies, surgeries, and laboratory works on the individuals with contagious diseases, (2) infected bodies of animals undergoing experiments in laboratories, (3) infectious materials collected from the patients which have been isolated in specific wards. These materials include body fluids, clothes, swabs, glassware substances, gloves used in surgeries, or bandages stained by infected wounds, feces, sputum, etc., and (4) other substances that were in touch with infected individuals. There are several sources that produce healthcare wastes such as hospitals, animal research centers, nursing homes, ambulance service providers, mortuaries, laboratories, wards of drug addicts, dental clinics, etc. All these establishments in this study have been considered as healthcare centers. Non-infectious wastes are non-hazardous substances that are not toxic, genotoxic, flammable, corrosive, etc. (Marinković et al., 2008). This type of wastes poses no health risk and there is no need for a particular method to disinfect them. Expired drugs, blister packs, and plasters are examples of non-infectious wastes.

Despite the existence of considerable number of studies on the healthcare waste management, many modifications can be applied to this field in order to capture practical aspects of this problem. One of the most important concepts that can be added to the logistic network of healthcare wastes is the emission of contamination when these wastes are transported from healthcare centers to the treatment centers. Therefore, one of the contributions of this study is to incorporate the concept of releasing hazardous emissions to the environment. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2014) has offered a handbook on safe management of healthcare wastes. In this handbook, the WHO offers some advice for preventing and handling spillages that proves the possibility of hazardous emissions to the surroundings during transportation. To see this handbook, please visit “https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/health-care-waste” and “https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/publications/wastemanag/en/”. Moreover, the WHO discussed various key factors on sound management of healthcare wastes. This means that managing healthcare wastes is a challenging and worldwide issue in real life. Therefore, different aspects of healthcare waste management such as transportation of these wastes should be tackled more accurately. According to the aforementioned reasons, the motivation of the current study is justified. In the proposed logistic network of this study, the infectious wastes are transferred to the treatment centers, while the non-infectious substances are required to be treated in recycling centers. Therefore, it is vital to separate the infectious wastes from the non-infectious materials in the healthcare centers. Since the infectious wastes are not neutralized properly or thoroughly in healthcare centers, risks are inevitable for the workers and the environment. The emission of contamination has a stochastic essence since it depends on various factors such as the length of transferring times. Hence, it is significant to consider the probability of hazardous emissions in designing a logistic network for healthcare wastes. An example which intensifies the importance of this research is the pandemic of the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) that generates considerable volume of medical wastes in each day. Therefore, there is a necessity for safe management of such wastes especially when these wastes are moved off-site. More information can be found at the WHO guidance, “Safe management of wastes from health-care activities” (WHO, 2014).

As another contribution, this research proposes a bi-objective model for the healthcare waste location-routing problem. Due to transportation of infectious wastes in the healthcare logistic network, it is possible that the emissions grow larger as the transportation time increases, and therefore the surrounding environment will be at risk. In the proposed model, transferring times between healthcare and treatment centers have been considered as normal random variables. In this research, the transferring times have been acquired from a real-life case study and they are proven to have normal distribution by conducting normality test. To integrate the stochastic essence of the emissions to the problem, the emission values are treated as random variables as well. The fleet of vehicles is heterogeneous, and there are time windows for visiting healthcare centers. The objectives of the model are to minimize total costs and release of contamination, concurrently. The location-routing problem is NP-hard because of its high intricacy (Nagy and Salhi, 2007, Samanlioglu, 2013). Therefore, the complexity of this problem convinced the authors to use multi-objective meta-heuristics in order to find high quality solutions within reasonable running times. The researchers have extended the contribution of this study by developing a Multi-Objective Water-Flow like Algorithm (MOWFA) to optimize the objectives. The MOWFA uses a heuristic based on a Multi-Attribute Decision Making (MADM) approach to rank non-dominated solutions so as to generate more appropriate offspring from the best ranked individuals. For the local search of the proposed algorithm, we designed two new neighborhood operators to find new solutions with respect to the solution representation and solution space of the problem. A dataset consisting of 45 test problems has been generated. To assess the performance of the proposed algorithm, two other methods have been utilized to solve the problem. A comprehensive set of experiments has been conducted and the results from implementation of all methods have been discussed.

The rest of this research is formed as follows: Section 2 discusses the literature and elaborates on the research gap which has been tackled in this study. Section 3 details the problem and the proposed mathematical model is presented. Section 4 develops a new algorithm based on the classical version of the water-flow like algorithm (Yang and Wang, 2007) to solve the problem. Experimental comparisons are made between the proposed method and two other meta-heuristics in Section 5. Section 5 also introduces a large-size real case study in Iran to demonstrate the practicality of our model and prove the efficacy of the proposed algorithm in providing diverse scenarios for decision makers. This paper has been concluded in Section 6 and some suggestions for future studies are provided in this section as well.

2. Related works

Nowadays, the production of medical wastes, along with its environmental and economic difficulties, has challenged urban management systems regarding collection, treatment, recycling, and disposal of these wastes. A great share of waste management costs is associated with waste collection, transportation, treatment, and recycling. In this respect, focusing on assessment and optimization of waste management systems can lead to reduction of issues (Babaee Tirkolaee et al., 2019). The problem of medical waste collection is a variant of the Vehicle Routing Problem (VRP). The VRP has a widespread practicality in well-known problems such as supply chain management, transportation, communications, etc. Because of detrimental threat of medical wastes to human health and environment, we have seen a growing interest in waste collection problems (Nolz et al., 2014). Since there are many influential factors that affect a healthcare waste network, there exists significant research gaps that should be tackled to provide more realistic solutions for real-life networks. A healthcare waste network comprises different factors such as treatment, recycling, and disposal centers. Treatment centers are set up to decrease or sterilize hazards of wastes. The process of treatment is supposed to disinfect wastes such that there will be no danger for subsequent disposal or recycling. For treating wastes, there are several available technologies that can be used to neutralize infectious wastes: (1) Incineration of wastes: through incinerating wastes, pathogens will be destroyed and turned into ashes. Pyrolysis and gasification are alternative thermal-based treatment technologies, (2) Autoclave devices: these devices utilize steam along with pressure to lessen the amount of microbiological entities in infectious wastes to a safe level at which these wastes can be recycled or dumped without high risk. Autoclaves are common tools which are usually used for disinfecting biomedical wastes, (3) Microwave irradiation: this technology operates based on non-contact heating infectious materials. Microwave irradiation requires less cycle time comparing to some other technologies, (4) Ethylene Oxide (EO) sterilization: In the EO technology, the sterilization process is carried out via a low temperature gas. In this method, the surface of materials are sterilized by a vacuum-based process. Since the EO uses low temperature gas, it is suitable for a wide range of materials. Through the EO sterilization, the cellular metabolism and reproduction of microorganisms are prevented.

Other than treating wastes, the process of recycling these materials is a factor of high importance as well. Recycling can be considered as a waste removal strategy in the healthcare industry. By recycling healthcare wastes, the consumption of raw materials will be decreased, and consequently the amount of wastes that must be dumped in a disposal site will be lessened as well.

Another main factor in the healthcare waste chain is the disposal centers. If the disposal centers are not appropriately constructed, the untreated medical wastes can contaminate potable, surface, and ground waters. Absence of proper waste disposal systems is a major issue associated with healthcare wastes. To investigate whether the previous studies have considered these important factors in their proposed healthcare networks or not, the authors have decided to extract these elements from the existing researches and provide a summary of literature in Table 1 . Moreover, the details of the most relevant studies have been reviewed as well: Shih and Chang (2001) designed a computer system for the infectious waste collection problem. This computer system has been used to: (1) determine routes for the collection vehicles, and (2) assign routes to each day of the week. Sheng et al. (2006) used the fuzzy measure method, weighting approach, and compromised programming method to solve the vehicle routing problem for transferring hospital materials. Nuortio et al. (2006) presented a conceptual model for the waste collection problem and applied it in a real-case study in Eastern Finland. They also developed a Guided Variable Neighborhood Thresholding (GVNT) algorithm. A mixed-integer mathematical model has been developed by Alumur and Kara (2007) for the hazardous location-routing problem. Alagöz and Kocasoy (2008) evaluated the optimum routes by means of software programs such as MapInfo and Roadnet for collecting healthcare wastes in Istanbul, Turkey. A geographic information-based system has been developed by Shanmugasundaram et al. (2012) for the healthcare waste management problem. Samanlioglu (2013) presented a multi-objective model for the location-routing problem which has been used for managing industrial hazardous wastes in the Marmara region of Turkey. The proposed model aimed to minimize total costs, transportation risk, and total risk for the population existing around the disposal and treatment sites. Hachicha et al. (2014) modeled the off-site transportation of infectious healthcare wastes as a Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP). Nolz et al. (2014) focused on an inventory routing problem and they applied it for the collection of infectious medical materials. Zhao et al. (2016) developed improved approaches for the network design problem that has been applied in a hazardous waste management system. They have used three multi-objective optimization methods including: (1) Weighted-Sum Method (WSM), (2) Augmented Weighted Tchebycheff Method (AWTM), and (3) Augmented ε-constraint Method (AECM) to solve the proposed problem. Naji-Azimi et al. (2016) focused on the Multi-Trip Vehicle Routing Problem (MT-VRP) for transportation of biomedical samples. They considered a time window for each request and tried to desynchronize the arrivals of biomedical samples through managing: (1) routes ordering, and (2) departure times of vehicles. The researchers developed a multi-start heuristic to solve the model. A grey-AHP approach has been proposed by Thakur and Ramesh (2017) for selecting a healthcare waste disposal strategy in Uttarakhand, Northern State of India. An optimization model has been proposed by Mantzaras and Voudrias (2017) for collection, transportation, treatment, and disposal of healthcare wastes. Hajar et al. (2018) studied the on-site medical waste collection problem and modeled it as a vehicle routing problem with time windows. Rabbani et al. (2018a) proposed a multi-objective model for collection of hazardous wastes. Their proposed model targeted to minimize: (1) transportation and construction costs, (2) population and environmental risks. They developed an augmented -constraint method to solve the problem. In another study, Rabbani et al. (2018b) developed a new model for the industrial hazardous waste locating-routing problem, where there are compatibility restrictions between some types of wastes. To find solutions to their model, they used two meta-heuristics, namely the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) and Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) algorithm. Wichapa and Khokhajaikiat (2018) focused on the location routing problem for the disposal of infectious wastes. They developed a hybrid approach consisting of the AHP, Genetic Algorithm (GA), and Goal Programming (GP) method. Baradaran et al. (2019) studied the stochastic vehicle routing problem, where the fleet of collection vehicles is heterogeneous and there are several prioritized time windows for visiting demand nodes. They developed an Artificial Bee Colony (ABC) method to solve the problem. Babaee Tirkolaee et al. (2019) proposed a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model for the multi-trip VRP with time windows in an urban waste collection network. They developed a Simulated Annealing (SA) method to solve the proposed model. Khoukhi et al. (2019) developed a genetic algorithm for the multi-trip VRP with time windows and concurrent pickup and delivery, where a fleet of homogeneous vehicles is used to service a set of hospitals. Ghaderi and Burdett (2019) proposed a two-stage stochastic programming model as an integrated location and routing approach for hazardous materials transportation in multi-modal transportation systems. In the first stage, strategic decisions are made concerning the location of transfer yards and in the second stage, hazmat routing is performed.

Table 1.

Summary of the most related studies.

| Research |

Problem |

Algorithm | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Multi-objective |

Recycling center |

Treatment center |

Time windows |

Heterogeneous fleet |

Emissions |

Healthcare |

|||||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | ||

| Shih and Chang (2001) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | LINGO | |||||||

| Sheng et al. (2006) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Compromised programming method + Fuzzy measure method + Weighting method | |||||||

| Nuortio et al. (2006) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | GVNT | |||||||

| Alumur and Kara (2007) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | CPLEX | |||||||

| Alagöz and Kocasoy (2008) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | MapInfo + Roadnet | |||||||

| Samanlioglu (2013) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Lexicographic weighted Tchebycheff | |||||||

| Hachicha et al. (2014) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | CPLEX | |||||||

| Nolz et al. (2014) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Sampling method + Adaptive large neighborhood search | |||||||

| Zhao et al. (2016) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | WSM, AECM, AWTM | |||||||

| Naji-Azimi et al. (2016) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | Multi-start heuristic | |||||||

| Mantzaras and Voudrias (2017) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | GA + Monte Carlo simulation | |||||||

| Hajar et al. (2018) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | CPLEX | |||||||

| Rabbani et al. (2018a) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | AECM | |||||||

| Rabbani et al. (2018b) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | NSGA-II, MOPSO | |||||||

| Wichapa and Khokhajaikiat (2018) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | AHP + GP + GA | |||||||

| Baradaran et al. (2019) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ABC | |||||||

| Babaee Tirkolaee et al. (2019) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | SA | |||||||

| Khoukhi et al. (2019) | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | GA | |||||||

| This paper | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | MOWFA + MOICA + MOSA | |||||||

By reviewing the literature, it has become clear for the authors that the emission of contamination along with other real-life constraints in healthcare logistics transportation can be an interesting topic to focus on. Having reviewed the previous studies, this paper offers the following contributions to the literature:

-

1.

According to the summary of previous studies shown in Table 1, it is obvious that there is still a need for considering emission of contamination in a healthcare logistic network. Therefore, a mixed-integer mathematical model has been proposed for the healthcare waste location-routing problem considering stochastic transferring times and emission of contamination.

-

2.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the performance of a water-flow like algorithm has not been investigated on a healthcare waste location-routing problem. Hence, a modified version of this method is developed for the proposed problem. Evaluating the performance of a modified water-flow like algorithm in solving a healthcare transportation problem with the mentioned features was a challenge for the authors that has been tackled in this research. The effectiveness of the proposed algorithm has been demonstrated by means of computational experiments.

-

3.

The proposed algorithm utilizes an MADM-based procedure for generating proper offspring.

-

4.

Two neighborhood operators have been devised for the MOWFA for finding better solutions.

3. Problem statement

3.1. Problem description and notations

This study tries to provide a new mathematical formulation for the healthcare waste location-routing problem. The concern regarding the emission of hazardous contamination during transportation of infectious wastes persuaded us to incorporate this concept into the proposed formulation. The developed model has been designed for two types of wastes which are known as infectious and non-infectious wastes. Both infectious and non-infectious wastes are generated at healthcare centers. Infectious and non-infectious wastes are separated from each other in healthcare centers by trained employees. A heterogeneous fleet of vehicles has been considered to collect infectious and non-infectious wastes, separately. Hence, any interaction between these two types of wastes is avoided. Collection vehicles have limited capacity. The number of available vehicles is predefined and fixed. There are some standards for containers of the vehicles used for collection of infectious wastes. The vehicles for collecting infectious wastes are usually equipped with rigid, tamper-proof, and puncture-resistant containers. These containers are impermeable and made of high-density plastics or metals that maintain the wastes safely and prevent any liquid leakage (WHO, 2014). However, these standards are not met in all countries due to high costs and unavailability of the containers with the aforementioned specifications. In the absence of these standards, there is a possibility of emission of contamination to the surroundings. Hence, the proposed model of this paper has incorporated this possibility to minimize the risk of exposure to contamination. In the proposed model, it is not allowed to collect the wastes of a healthcare center partially. The whole amount of each waste type produced at a healthcare center cannot be more than the capacity of the vehicle that is assigned for collection of that type of waste. To collect each type of waste, each healthcare center is visited precisely once by merely one vehicle.

The proposed network consists of four main elements: a set of healthcare centers, and three sets of facilities including treatment, recycling, and disposal centers (Rabbani et al., 2018b). Treatment, recycling, and disposal centers are capacitated. The locations of healthcare centers are known and predefined. However, the locations of treatment, recycling, and disposal centers are determined by the proposed model. A limited number of treatment, recycling, and disposal centers can be established. After visiting a set of healthcare centers, a collection vehicle has two options to drop off its load: (1) if its load is infectious, the vehicle moves to a treatment center, and (2) if its load is non-infectious, the vehicle will visit a recycling center. After treating the infectious wastes, the residues can be either recyclable or non-recyclable. Recyclable wastes are moved to recycling centers, while the others are transferred to disposal centers. Waste residues that are generated by the recycling process will also be transported to disposal centers. The technologies used in treatment centers to treat infectious wastes are not the same. Each treatment center can be established with at most one treatment technology. Time windows are considered for collecting infectious and non-infectious wastes from healthcare centers. Violating a time window will cost a penalty on the network. The time-lapse between generation and treatment of wastes must not exceed 72 h in winter and 48 h in summer. However, due to limitation of space in healthcare centers, both types of wastes must be collected on daily basis. All amounts of infectious and non-infectious wastes must be collected from healthcare centers. All parameters are deterministic except for the traveling times between the healthcare and treatment centers. Graphical display of this network has been depicted in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Graphical display of the proposed network.

The notations used to formulate the proposed model are introduced below:

| Sets: | |

|---|---|

| Set of infectious wastes (. | |

| Set of non-infectious wastes (. | |

| Set of healthcare centers (. | |

| Set of treatment centers (. | |

| Set of recycling centers (. | |

| Set of disposal centers (. | |

| Set of treatment technologies (). | |

| Set of vehicles for collection of infectious wastes (). | |

| Set of vehicles for collection of non-infectious wastes (). | |

| Parameters: | |

| Cost of setting up the treatment center with the technology. | |

| Cost of setting up the recycling center. | |

| Cost of setting up the disposal center. | |

| Cost of fuel (per unit). | |

| Fixed cost of utilizing the vehicle to collect infectious wastes. | |

| Fixed cost of utilizing the vehicle to collect non-infectious wastes. | |

| Treatment cost of the infectious waste in the treatment center with the technology. | |

| Recycling cost of the infectious waste in the recycling center. | |

| Disposal cost of the infectious waste in the disposal center. | |

| Recycling cost of the non-infectious waste in the recycling center. | |

| Disposal cost of the non-infectious waste in the disposal center. | |

| Per unit cost of transferring the infectious waste from the healthcare center to the treatment center. | |

| Per unit cost of transferring the infectious waste from the treatment center to the recycling center. | |

| Per unit cost of transferring the infectious waste from the treatment center to the disposal center. | |

| Per unit cost of transferring the infectious waste from the recycling center to the disposal center. | |

| Per unit cost of transferring the non-infectious waste from the healthcare center to the recycling center. | |

| Per unit cost of transferring the non-infectious waste from the recycling center to the disposal center. | |

| Distance between the healthcare centers and (). | |

| Distance between the healthcare center and the treatment center. | |

| Distance between the healthcare center and the recycling center. | |

| Distance between the treatment center and the recycling center. | |

| Distance between the treatment center and the disposal center. | |

| Distance between the recycling center and the disposal center. | |

| Transferring time between the healthcare centers and (). | |

| Transferring time between the healthcare center and the treatment center. | |

| Available capacity of the vehicle for collection of infectious wastes. | |

| Available capacity of the vehicle for collection of non-infectious wastes. | |

| Available capacity of the treatment center. | |

| Available capacity of the recycling center. | |

| Available capacity of the disposal center. | |

| Lower bound of the time window considered for collection of infectious wastes from the healthcare center. | |

| Upper bound of the time window considered for collection of infectious wastes from the healthcare center. | |

| Lower bound of the time window considered for collection of non-infectious wastes from the healthcare center. | |

| Upper bound of the time window considered for collection of non-infectious wastes from the healthcare center. | |

| Quantity of the infectious waste generated by the healthcare center. | |

| Quantity of the non-infectious waste generated by the healthcare center. | |

| Maximum number of treatment centers. | |

| Maximum number of recycling centers. | |

| Maximum number of disposal centers. | |

| Rate of recyclable infectious waste in the treatment center with the treatment technology. | |

| Rate of recyclable infectious waste in the recycling center. | |

| Rate of recyclable non-infectious waste in the recycling center. | |

| Emission coefficient of the infectious waste (. | |

| Penalty cost imposed on the network if a time window is violated. | |

| A considerably large number. | |

| =1, if the treatment center has the treatment technology; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the infectious waste can be treated by the technology; otherwise, =0. | |

| Decision variables: | |

| Amount of time violated by the vehicle in visiting the healthcare center for collecting infectious wastes. | |

| Amount of time violated by the vehicle in visiting the healthcare center for collecting non-infectious wastes. | |

| Amount of the infectious waste received by the treatment center from the healthcare center using the vehicle. | |

| Amount of the infectious waste received by the recycling center from treatment center using the vehicle. | |

| Amount of the infectious waste received by the disposal center from the treatment center using the vehicle. | |

| Amount of the infectious waste received by the disposal center from the recycling center using the vehicle. | |

| Amount of the non-infectious waste received by the recycling center from the healthcare center using the vehicle. | |

| Amount of the non-infectious waste received by the disposal center from the recycling center using the vehicle. | |

| Entrance time of the vehicle in the healthcare center (For collecting infectious wastes). | |

| Entrance time of the vehicle in the healthcare center (For collecting non-infectious wastes). | |

| Amount of emission of contamination while transferring the infectious waste. | |

| First objective function (total costs of the network). | |

| Second objective function (total emission of contamination). | |

| =1, if the treatment center is established with the technology; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the recycling center is established; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the disposal center is established; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the vehicle is used for collection of infectious wastes; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the vehicle is used for collection of non-infectious wastes; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the vehicle is allocated to the treatment center; otherwise, =0 (For infectious wastes). | |

| =1, if the vehicle is allocated to the recycling center; otherwise, =0 (For infectious wastes). | |

| =1, if the vehicle is allocated to the recycling center; otherwise, =0 (For non-infectious wastes). | |

| =1, if the vehicle is allocated to the disposal center; otherwise, =0 (For infectious wastes). | |

| =1, if the vehicle is allocated to the disposal center; otherwise, =0 (For non-infectious wastes). | |

| =1, if the vehicle is selected to travel from the healthcare center to the healthcare center; otherwise, =0 (For infectious wastes). | |

| =1, if the vehicle is selected to travel from the healthcare center to the healthcare center; otherwise, =0 (For non-infectious wastes). | |

| =1, if the treatment center has used the technology to treat the infectious waste; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the vehicle carries infectious wastes from the healthcare center to the treatment center; otherwise, =0. | |

| =1, if the vehicle carries non-infectious wastes from the healthcare center to the recycling center; otherwise, =0. | |

3.2. Mathematical formulation

Based on the assumptions mentioned in Section 3.1, a bi-objective mixed-integer programming model is proposed for the healthcare waste location-routing problem that aims to: (1) determine the routes of vehicles for collecting infectious and non-infectious wastes, (2) Specify the technology that is used by each treatment center, (3) determine the locations of treatment, recycling, and disposal centers, (4) estimate the costs of this network, (5) estimate the amount of emission that will be released to the environment. The formulation of the proposed model is as follows:

| (1.a) |

Eq. (1) is the first objective function of the model that targets to minimize the total costs of the network. The first objective function is formulated by summing Eqs. (1.a), (1.b), (1.c), (1.d), (1.e), (1.f), (1.g), (1.h), (1.i). Eq. (1.a) is associated with the costs of establishing facilities.

| (1.b) |

Eq. (1.b) formulates the fixed costs of utilizing collection vehicles.

| (1.c) |

Eq. (1.c) obtains the costs of treating infectious wastes.

| (1.d) |

Recycling costs of both types of wastes are formulated in Eq. (1.d).

| (1.e) |

Eq. (1.e) computes the costs of disposing of both infectious and non-infectious wastes.

| (1.f) |

Eq. (1.f) formulates the costs of transferring infectious wastes.

| (1.g) |

The costs of transferring non-infectious wastes have been formulated in Eq. (1.g).

| (1.h) |

Eq. (1.h) obtains the costs of violating time windows.

| (1.i) |

Eq. (1.i) calculates the costs of fuel for the utilized vehicles.

| (2) |

The second objective function is formulated in Eq. (2) that minimizes the emission of contamination to the environment.

Subject to:

| (3) |

Constraint (3) implies that the amount of infectious wastes received by a treatment center cannot exceed the capacity of that treatment center.

| (4) |

Constraint (4) ensures that the amount of wastes (infectious and non-infectious) received by a recycling center cannot be more than its capacity.

| (5) |

Constraint (5) guarantees that all amounts of wastes collected by a disposal center cannot exceed its capacity.

| (6) |

| (7) |

Constraints (6), (7) guarantee that all available wastes in this network are collected from healthcare centers.

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Constraints (8), (9), (10) indicate that a vehicle must leave the corresponding node of a healthcare center after completion of its service.

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

| (16) |

Constraints (11), (12), (13), (14), (15), (16) ensure that the vehicles do not carry more than their capacities.

| (17) |

Constraint (17) ensures that the required technology is available in treatment centers for infectious wastes.

| (18) |

| (19) |

Equations (18), (19) guarantee that each healthcare center is visited exactly once.

| (20) |

Constraint (20) implies that each treatment center can be established with at most one treatment technology.

| (21) |

| (22) |

| (23) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

Constraint (21), (22), (23), (24), (25) state that the vehicles must be assigned to a facility.

| (26) |

| (27) |

Constraints (26), (27) state that only one vehicle is assigned to the route between healthcare and treatment / recycling centers.

| (28) |

| (29) |

| (30) |

| (31) |

Violations of time windows have been obtained in Constraints (28), (29), (30), (31).

| (32) |

Eq. (32) computes the amount of contamination that is released to the environment during transferring the infectious waste to treatment centers.

| (33) |

| (34) |

| (35) |

Constraints (33), (34), (35) satisfy the limitations on the number of facilities.

| (36) |

Constraint (36) secures that each collection vehicle which has been assigned to carry infectious wastes must drop its load at a treatment center with the compatible treatment technology.

| (37) |

| (38) |

Constraints (37), (38) secure the evasion of sub-tours.

| (39) |

| (40) |

| (41) |

| (42) |

Equations (39), (40), (41), (42) imply the flow balance between facilities.

4. (43)

| (44) |

Finally, Constraints (43) and (44) show positive and binary variables, respectively

Lemma.

This lemma is presented to deliver better understanding for calculating the second objective function values. In the proposed model, the travel times between healthcare and treatment centers are normal random variables as . Therefore, we have ), where it is possible to obtain and by the Equations (45), (46) , respectively.

| (45) |

| (46) |

Proof.

Let assume that , therefore, is obtained as . According to Eq. (26), we have = 1. Hence, and . The generalized perspective for all infectious wastes proves this lemma.

5. Solution methodology

The location-routing problem is known to have an NP-hard nature, which implies that it is complicated to find optimal solutions for large-sized problems (Yildiz et al., 2013). Besides, the proposed model in this research has a non-linear essence, and therefore it is justifiable to use multi-objective meta-heuristics for solving this problem. Hence, this paper employs two multi-objective meta-heuristic algorithms to tackle the problem. In addition to these methods, we have developed a hybrid version of the WFA that differs from the classical version of this method in several perspectives. All employed algorithms are capable of searching for the solution space of the proposed problem in order to find a set of non-dominated solutions for the decision maker to choose from.

5.1. Representation scheme of solutions

One of the remarkable factors that influences the complexity and required computational time of evolutionary methods is the representation scheme of solutions (Chen et al., 2013). Using a proper solution representation may lead the algorithm to all possible candidate solutions (Rabbani et al., 2018b). To encode the potential solutions of the problem tackled in this paper, we have used the order-based representation scheme which has been used widely in the literature. In this encoding scheme, each solution is a ( matrix, where WT, NF, and NSN represent the number of waste types, centers, and demand nodes, respectively. The first WT rows of a solution are permutations whose elements are in the range . The other rows are dedicated to the order of treatment, recycling, and disposal centers. It is possible that these rows have empty cells (Rabbani et al., 2018b). Suppose that there is a logistic network with dimension , which means that this network consists of ten healthcare centers, five treatment centers, four recycling centers, and three disposal centers, respectively. An illustrated example of a solution for this network has been depicted in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

An illustrated example of the solution representation scheme.

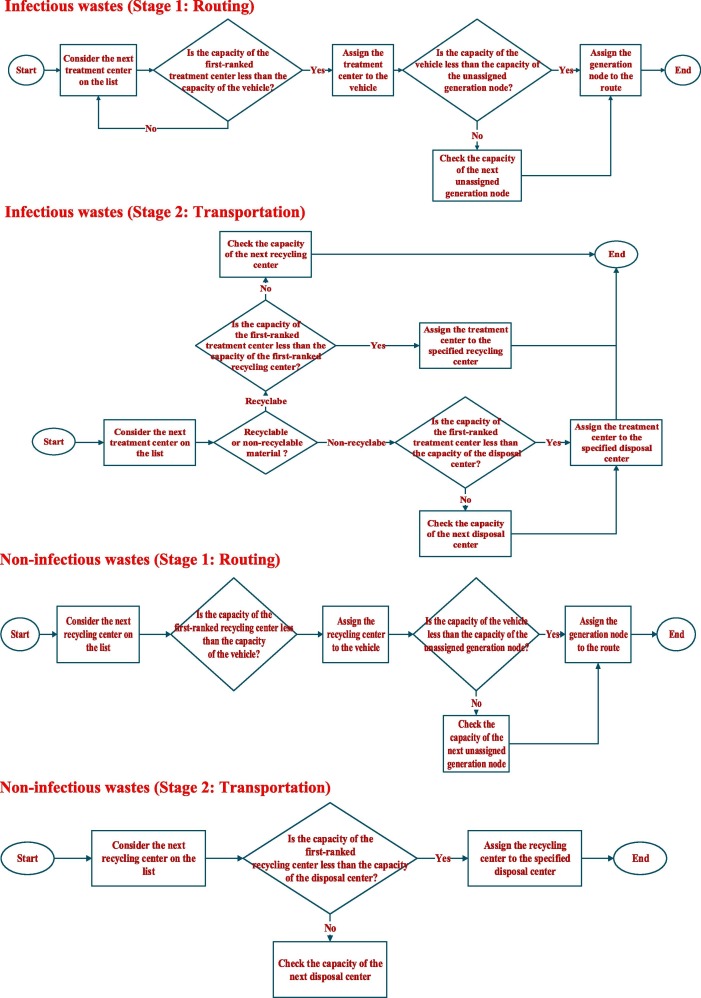

A two-stage decoding procedure is required to transform this representation scheme into meaningful solutions and obtain the objective function values. The first stage is dedicated to the routing dimension of the problem, while the second stage tackles the transportation aspect of the problem. In the first stage, feasible routes for collection vehicles are determined based on their destination nodes. The destination node of a collection vehicle is considered as a treatment, recycling, or disposal center that its remaining capacity is equal to or greater than the capacity of the corresponding vehicle. Having determined the proper center for unloading a vehicle, its collection route will be determined. Hence, an assignment procedure is needed to determine the routes of vehicles. This procedure starts with assigning the first-ranked unassigned node to the route and it continues until no more generation nodes can be added to the route considering the limitations of vehicles. The second stage of the decoding procedure is dedicated to determining the amount of waste residues that should be transferred between different centers. The second stage starts with assigning the residues of the first-ranked treatment center to the first-ranked recycling and disposal centers. This process continues with the rest of the treatment centers according to the ordered list until the remaining capacity of the recycling and disposal centers cannot embrace residues of other treatment centers. The same procedure is applied to transfer non-recyclable wastes from recycling centers to disposal centers (Rabbani et al., 2018b). Fig. 3 displays the flowchart of the two-stage decoding procedure. Each vehicle passes through these steps regarding the type of its waste.

Fig. 3.

Flowchart of the decoding procedure.

5.2. Water-Flow like algorithm (WFA)

Yang and Wang (2007) have been motivated by the water-flow behavior in traveling through different terrains to introduce a meta-heuristic, namely the Water-Flow like Algorithm (WFA) for optimization problems. In the WFA, water-flows and terrains are considered as solutions and search space, respectively. The WFA operates based on several procedures (Yang and Wang, 2007, Nourmohammadi et al., 2019): (1) Splitting and moving procedures, (2) Merging, (3) Evaporation, and (4) Precipitation. In order to save space, the procedures of the classical WFA have been explained in Appendix A.

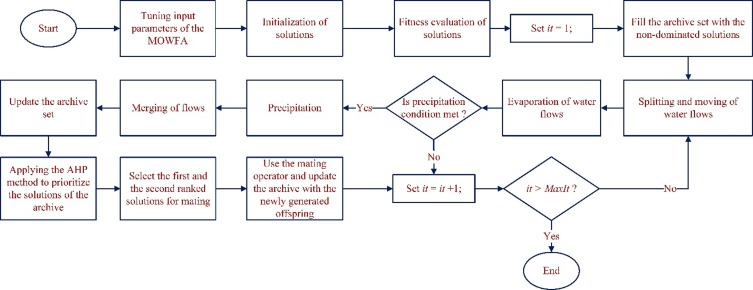

5.3. Multi-Objective Water-Flow like algorithm (MOWFA)

This section introduces the modifications offered in this research for the water-flow like algorithm. One of these modifications has occurred in the splitting and moving procedures of the WFA. In the proposed algorithm, for each original flow, a real random number (RRN) on the interval is generated. Each original flow is substituted by its sub-flows if: (1) the original flow is dominated by at least one of its sub-flows, or (2) the random number RRN is equal to or more than 0.5. Otherwise, the sub-flows are neglected and the original flow is used once again to produce NOSF number of new sub-flows. This procedure forces the MOWFA to find better solutions and enhances the quality and diversity of non-dominated solutions, simultaneously. The first condition helps to detect more appropriate solutions in terms of quality, while the second condition enables the MOWFA to find more diverse solutions. Similar to many other multi-objective optimization methods, the non-dominated solutions found in each iteration of the MOWFA are stored in an archive set.

To find the non-dominated solutions of each iteration, the non-dominated sorting technique proposed by Deb et al. (2002) has been used. In this technique, each individual is compared with other individuals of population to determine the first front of non-dominated solutions. A multi-objective optimization problem comprises a set of minimizing or maximizing objectives defined over a solution space. For the proposed model with two minimization objectives, a solution is dominated by another solution if we have for both objectives and there will be at least one objective such that. This means that the solution dominates the solution if the objective values of solution are less than or equal to the objective values of solution, and at least one objective value of is less than the one assessed at solution.

The newly found non-dominated solutions are compared to the existing solutions of the archive. A newly found solution becomes a member of the archive if it is not dominated by the solutions of the archive. The dominated solutions of the archive will be eliminated from this set. As another modification to the classical WFA, we propose a new procedure based on the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) and the solutions stored in the archive set. The AHP is a well-known Multi-Attribute Decision Making (MADM) approach proposed by Saaty (1987) to determine the weights of criteria and rank the alternatives. Since the solutions existing in the archive set are the best found solutions during the optimization process, the proposed approach is implemented on these solutions so that more proper solutions might be found in their neighborhoods. In each iteration, the AHP method is applied to the solutions of the archive set, and therefore the weights of the criteria are obtained and the solutions are ranked. The hierarchy used in the MOWFA has three different levels: (1) goal, (2) criteria, and (3) alternatives. Fig. 4 shows an illustration of this hierarchy. The objective functions are considered as the criteria in the AHP method and the solutions of the archive set are considered as alternatives. The relative weights of criteria are determined by means of pairwise comparisons. To conduct these comparisons, the judgments of the decision maker is adopted using the 9-point scale. Keeping the 9-point scale in mind, in the MOWFA, the first objective function has been referred to as “equally to moderately importance” over the second objective function. This means that the first objective function is twice as important as the second objective function for the decision maker. To calculate the weights of criteria, the arithmetic mean as an approximation method is used. The exact calculations have not been considered in the proposed algorithm since the complexity will be increased significantly without any necessity. In the next step, the non-dominated solutions existing in the archive set are compared with each other regarding each objective. The overall priority of alternatives are calculated through combining the weights of objectives with the priority weights of non-dominated solutions. Having ranked the solutions of the archive set, the first and the second ranked solutions are selected for mating. A mating operator is applied to the selected solutions, and therefore two new offspring are generated. It is noteworthy that in each iteration, the Consistency Index (CI) is computed to investigate whether the judgments are consistent or not. If the consistency index is determined to be less than 0.1, the solutions of the archive set are ranked and the best found solutions are selected for mating. Otherwise, the AHP procedure in the MOWFA is neglected for the current iteration and the mating procedure is not performed for the respective iteration.

Fig. 4.

Decision hierarchy for ranking solutions in the MOWFA.

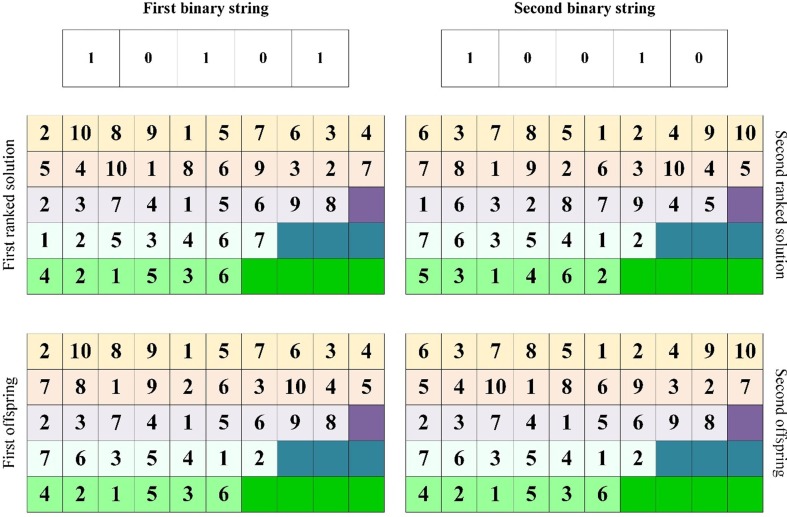

The mating operator generates two binary strings with the length, where WT and NF denote the number of wastes and facilities. Algorithm 1 describes the proposed procedure and the mating operator. Fig. 5 illustrates an example of producing two offspring from the selected solutions. In the next step, two generated offspring are used to update the archive set.

| Algorithm 1: Proposed approach for generating new offspring | |

|---|---|

| Notations: | |

| NOR | Number of rows in a solution (. |

| The element on the first random binary string. | |

| The element on the second random binary string. | |

| The row of the first selected solution. | |

| The row of the second selected solution. | |

| The row of the first offspring. | |

| The row of the second offspring. | |

| 1. | Generate two random binary strings; |

| 2. | FortoNORdo |

| 3. | Ifdo |

| 4. | |

| 5. | Else |

| 6. | |

| 7. | End if |

| 8. | Ifdo |

| 9. | |

| 10. | Else |

| 11. | |

| 12. | End if |

| 13. | End for |

| 14. | Update the archive set with the newly generated offspring; |

| 15. | Eliminate the dominated solutions from the archive set; |

| Output: An updated archive set. | |

In addition to the aforementioned modifications, the MOWFA uses two novel neighborhood operators (as local search methods in the splitting and moving procedures) to produce new feasible solutions from each water-flow. By using these operators, it is possible to find the solutions in the neighborhood of an existing water-flow. These neighborhood operators are elaborated in the following sub-sections. The MOWFA stops after a maximum number of iterations (. Fig. 6 shows the flowchart of the proposed algorithm.

Fig. 5.

Two offspring generated by the mating operator.

Fig. 6.

Flowchart of the proposed algorithm.

5.3.1. First neighborhood operator

A random integer number (RAIN) is generated on the interval [, where NSN denotes the number of demand nodes. The first RAIN columns of a solution is preserved, and several elements of other columns have to take new positions. In this respect, in each row, several elements existing on the columns to NSN are chosen randomly to change their positions. The pseudo-code of this operator is presented in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2: First neighborhood operator | |

|---|---|

| Notations: | |

| NSN | Number of demand nodes (Number of columns). |

| RAIN | A random integer number in the range of. |

| NOR | Number of rows in a solution (. |

| First random position number. | |

| Second random position number (. | |

| Number of used (non-empty) cells on the row. | |

| The value on the column and row. | |

| The value on the column and row. | |

| STR | A set to store random numbers. |

| 1. | Generate an integer random number (RAIN) on the ; |

| 2. | Preserve the first RAIN columns; |

| 3. | FortoNORdo |

| 4. | Empty the set STR; |

| 5. | Choose a random position ( in the range ; |

| 6. | Add to the set STR; |

| 7. | Choose a random position ( in the range ; |

| 8. | Ifdo |

| 9. | Swap the and ; |

| 10. | End if |

| 11. | End For |

| Output: A new feasible solution. | |

Fig. 7 shows an example of generating a new solution via the first neighborhood operator. According to this figure, the first four columns of the parent solution are transferred to the new solutions without any changes (). Then, the 5th to 10th columns of the solution are subject to changes in order to produce a new solution. In each row, two positions have been selected randomly and their values have been swapped.

Fig. 7.

A new solution generated by the first neighborhood operator.

5.3.2. Second neighborhood operator

To produce a new water-flow, two positions of each row are selected randomly, and the values on these positions are swapped. To select two random positions on each row (), we generate two random real numbers (and) on the interval. The numbers and are multiplied by the number of non-empty cells (used cells) on the row, and the results are rounded up. Therefore, two positions (and) are obtained and the values existing in these positions are substituted with each other. The pseudo-code of the second neighborhood operator is given in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3: Second neighborhood operator | |

|---|---|

| Notations: | |

| A real random number in the range [0, 1]. | |

| A real random number in the range [0, 1] (). | |

| First selected position on the row. | |

| Second selected position on the row. | |

| The value on the position. | |

| The value on the position. | |

| NOR | Number of rows in a solution (. |

| A set to store random numbers for the row. | |

| Number of used (non-empty) cells on the row. | |

| 1. | FortoNORdo |

| 2. | Generate a real random number ( on the interval ; |

| 3. | |

| 4. | Add to the set ; |

| 5. | Generate a real random number ( on the interval ; |

| 6. | Ifdo |

| 7. | |

| 8. | Swap the and ; |

| 10. | End if |

| 11. | End for |

| Output: A new feasible solution. | |

Fig. 8 illustrates a sample solution produced by means of the second neighborhood operator. According to the instructions given in Algorithm 3, for each row, two random numbers have been generated in the interval. In this respect, we have , and. Based on these random numbers, the candidate positions for swapping are obtained as , and. The values on these positions are swapped, and therefore a new solution is generated as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

A new solution generated by the second neighborhood operator.

5.4. Other employed algorithms

To investigate the success of the MOWFA in solving the proposed model, we have used two other meta-heuristics namely, the Multi-Objective Imperialist Competitive Algorithm (MOICA), and Multi-Objective Simulated Annealing (MOSA). The reason behind choosing these two well-known methods is that the MOICA and MOSA have been successful in solving various multi-objective problems (Hosseini and Al Khaled, 2014, Fathollahi-Fard et al., 2019)

5.4.1. Description of the MOICA

The imperialist competitive algorithm (ICA), as an evolutionary algorithm, has been inspired by socio-political evolutions. In the MOICA, each solution is considered as a country. Similar to political backgrounds, countries are either imperialist or colonies. Therefore, for each imperialist, there is a set of colonies. The algorithm searches for the best country during the optimization process. The best country has the best possible combination of socio-political features. These socio-political features include economic policy, culture, language, etc (Zandieh et al., 2017). To obtain different Pareto fronts, the MOICA hires the non-dominated sorting technique after producing initial population of countries. This algorithm utilizes the crowding distance metric to rank individuals of each front. For the MOICA, there is an archive set that stores non-dominated individuals of the first Pareto front in each iteration. By using the non-dominated sorting technique and crowding distance metric, the best countries (solutions) are chosen from the population and they are regarded as imperialists. The rest of the countries are considered as colonies. The power of each imperialist should be evaluated to determine its share of the colonies. In other words, the more the power of an imperialist, the greater its share of the colonies that can be allocated to it.

In each iteration of the MOICA, there is an assimilating movement in which the colonies of an imperialist move toward their respective imperialist. Through this movement, the features of colonies will become similar to the features of their corresponding imperialist. Therefore, the colonies of an imperialist are improved. For the MOICA, there is a revolution operator that enhances the exploration ability of the algorithm. This operator selects a random colony with a probability and revolves its position in the search space based on a random manner. Because of assimilation and revolution procedures, if a colony was found to be better than its imperialist, their positions would be exchanged. The imperialists compete with each other by seizing the weakest colonies of one another. The algorithm stops if a predefined termination criterion is met. In this research, an upper bound has been defined for the number of iterations and the algorithm will stop if it reaches this upper bound (Zandieh et al., 2017, Nabipoor Afruzi et al., 2014). The roots and basic concepts of this algorithm can be found in Atashpaz-Gargari and Lucas (2007).

5.4.2. Description of the MOSA

The simulated annealing (SA) is a renowned method inspired by physical annealing process in the field of metallurgy. This method has been developed based on the statistical mechanics concept. In the annealing process, proper low energy state crystallization is achieved by slow cooling of a metal. On the other hand, fast cooling will result in improper crystallization. Gradual reduction of high temperature to low temperature will lead to a crystalline state. Therefore, each temperature must be maintained for a sufficient amount of time so that the crystal will have enough time to reach the minimum energy state. The SA imitates the crystallization process in order to find optimal or near optimal solution.

This research employs the Multi-Objective Simulated Annealing (MOSA) which hires the concepts of dominance and Pareto optimality to converge to the Pareto optimal set. In addition to the convergence behavior, the MOSA utilizes the transition palpability to preserve appropriate spread of the solutions throughout the obtained Pareto front. One of the advantages of the MOSA over evolutionary algorithms is that this method requires no big memory to store the population. Hence, the MOSA can find an approximate Pareto front in a short running time (Zidi et al., 2012). The MOSA encounters two situations in search of the optimal solution. First, the algorithm finds a better solution than the current one. In this case, the better solution is accepted and the current one is discarded. Secondly, the MOSA finds worse solutions that are accepted according to an acceptance probability (Baños et al., 2013). The acceptance probability of new solutions when they are worse than the current solution depends on the temperature. The acceptance probability is low if the temperature is low. Conversely, in case of being worse than the current solution, the probability of accepting a new solution is high when the temperature is also high (Yannibelli and Amandi, 2013). The acceptance probability is determined based on the Boltzmann Probabilistic Distribution (Nino et al., 2012). This acceptance helps the MOSA to dodge the local optimum. The MOSA stores the non-dominated solutions in an unlimited size archive (Zidi et al., 2012). The newly found solution can be added to the archive if it is not dominated by any of the existing solutions in the archive set (Baños et al., 2013). The MOSA continues the optimization process until the temperature cools down below a predefined threshold.

6. Numerical analysis

This section provides several numerical experiments to evaluate the performances of the algorithms. The location-routing problem (LRP) is extremely complex to solve due to the fact that it belongs to the class of NP-hard problems. This complexity increases when the number of demand nodes or the candidates for location facilities are large. Using meta-heuristics for solving the problem is justifiable since the proposed model is more intricate than the classical LRP. Therefore, meta-heuristics are welcome to quickly find feasible solutions to large size instances of this problem (Prodhon and Prins, 2014). We used the MATLAB software (R2015b) to code the algorithms and we ran these methods on an Inter Corei3 personal computer (3.4 GHz CPU) with 8 GB of memory (RAM).

6.1. Generating test problems

To evaluate the MOWFA and compare its performance with the MOICA and MOSA, 45 test problems with different sizes are produced. The test problems 1 to 15 are small-sized problems, while the test problems 16 to 30 are medium-sized problems. The test problems 31 to 45 are considered as large-sized problems. The main parameters of the proposed problem and their ranges have been shown in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Characteristics of test problems.

| Parameters | Parameters |

|---|---|

* Note: denotes the uniform distribution, and represents the normal distribution.

6.2. Calibration of parameters

The performance of a meta-heuristic is affected by the values of its control parameters (Afshar-Nadjafi et al., 2017). Hence, in this section, the control parameters of the MOWFA are calibrated via the Taguchi Method (TM) to improve the efficiency of this algorithm. By using the Taguchi method, a large amount of information is obtained by conducting the least number of experiments (Hasçalık and Çaydas, 2008). In this study, a five-level Taguchi design has been considered for the parameters of the MOWFA. A total objective function (a convex combination of objectives) has been used as a response for the Taguchi designs. To dodge the trap of different measures, the objective function values are normalized. Normalized values of objectives for the solution ( and) are obtained using the following formulas:

| (47) |

| (48) |

Where, and denote the values of the first and the second objective functions for the solution, respectively. The best acquired values of the first and the second objectives are represented as and, respectively. For the solution, the total objective function () is computed by Eq. (49). represents the relative importance of the objectives.

| (49) |

In the next step, the total objective function values are converted into the Relative Percentage Deviation (RPD) which is computed by the Eq. (50) (Hosseinian and Baradaran, 2019a):

| (50) |

Where, represents the total objective function value obtained by a hired algorithm, and is the best value of the total objective function. The levels which have been considered for the parameters are shown in Table 3 . The chosen levels of parameters are reported in Table 4 . Besides, Fig. 9 depicts the average S/N ratio plots for the small, medium, and large size test problems. Other algorithms have been tuned by the same procedure.

Table 3.

Levels of input parameters.

| Parameters | Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | |

| 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 | 30 | |

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | |

| 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 |

Table 4.

Tuned values of parameters for the MOWFA.

| Parameters |

Problem size |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | Large | |

| 30 | 30 | 10 | |

| 10 | 20 | 30 | |

| 50 | 20 | 50 | |

| 500 | 500 | 500 | |

Fig. 9.

S/N ratio plots for parameters of the MOWFA: (a) small size problems, (b) medium size problems, and (c) large size problems.

6.3. Performance evaluation metrics

The literature of multi-objective optimization problems provides numerous metrics to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of multi-objective optimizers. This research hires several comparison metrics to evaluate the performances of the MOWFA, MOICA, and MOSA in obtaining more appropriate solution sets. These metrics are described as follows:

6.3.1. Computational time (CPU time)

We have employed two indexes introduced by Li et al. (2014) to compare the algorithms in terms of computational time. These metrics are denoted as ATO and ATA which represent the average computational time to find one solution, and the average computational time to obtain all solutions, respectively. These criteria are computed using the following formulas:

| (51) |

| (52) |

Where, is the number of obtained solutions in the run. RN represents the number of runs and denotes the computational time in the run.

6.3.2. Error ratio (ER)

The error ratio (ER) has been used in many multi-objective optimization studies. The ER is used to measure the non-convergence of an approximation Pareto front found by a multi-objective optimization algorithm towards the Pareto optimal front. This metric is calculated by the following formula (Yazdani et al., 2019):

| (53) |

Where, represents the number of non-dominated solutions on the approximation front obtained by an algorithm. is equal to 1 if the non-dominated solution found by a given algorithm belongs to the Pareto optimal front. Otherwise, is equal to 0. Smaller ER values indicate better performance of a method (Yazdani et al., 2019, Hosseinian et al., 2019, Veldhuizen, 1999).

6.3.3. Spacing metric (SM)

The spacing metric (SM), developed by Schott (1995), is a diversity-based performance measure that provides information on the distribution of solutions existing in an approximation Pareto front (Rabbani et al., 2018b). In a comparison of two Pareto sets, the approximation front with the lower SM value has a better uniformity of distribution of solutions. The SM is computed by the Eqs. (54), (55), (56) (Yazdani et al., 2019):

| (54) |

| (55) |

| (56) |

Where, is the set of non-dominated solutions on the Pareto front. denotes the minimum distance between the solution on the approximation front and other solutions. is the mean of all s. is the number of objective functions in the optimization problem. represents the value of objective function for the solution .

6.3.4. Maximum spread (MS)

Zitzler (1999) proposed the maximum spread (MS) metric, known as diversification metric, to measure the spread of the approximation Pareto front. The normalized MS metric is obtained by the Eq. (57) (Zitzler, 1999, Helbig and Engelbrecht, 2013, Yazdani et al., 2019):

| (57) |

6.4. Results and discussion

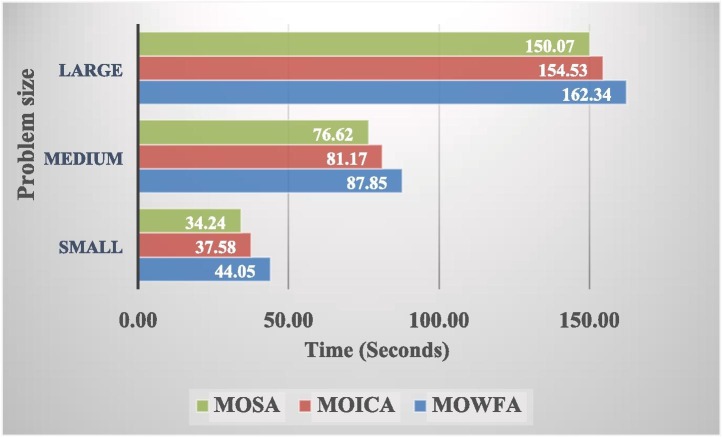

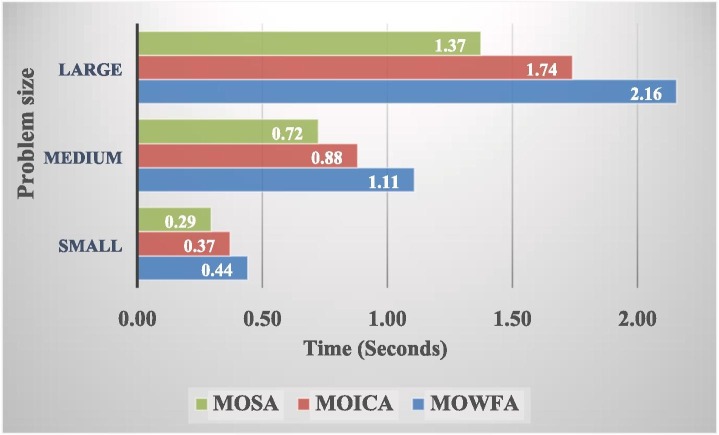

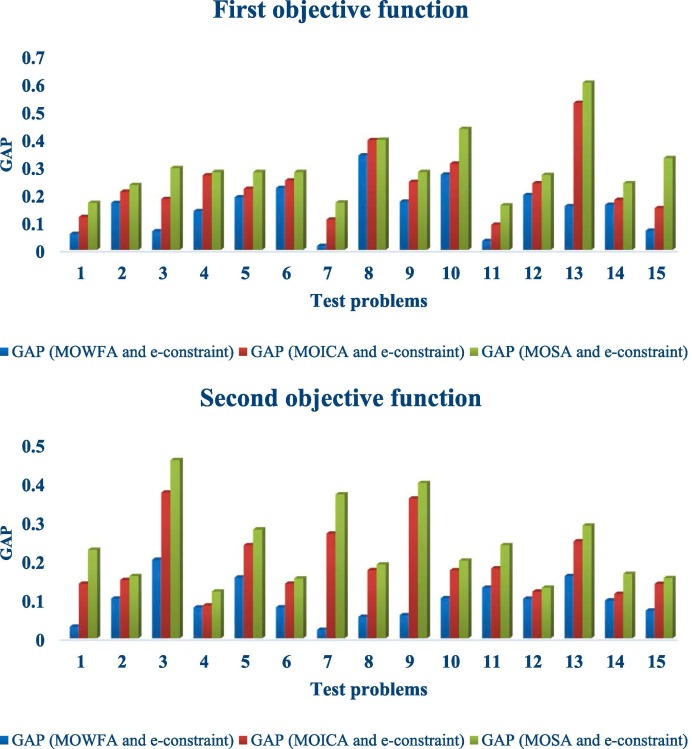

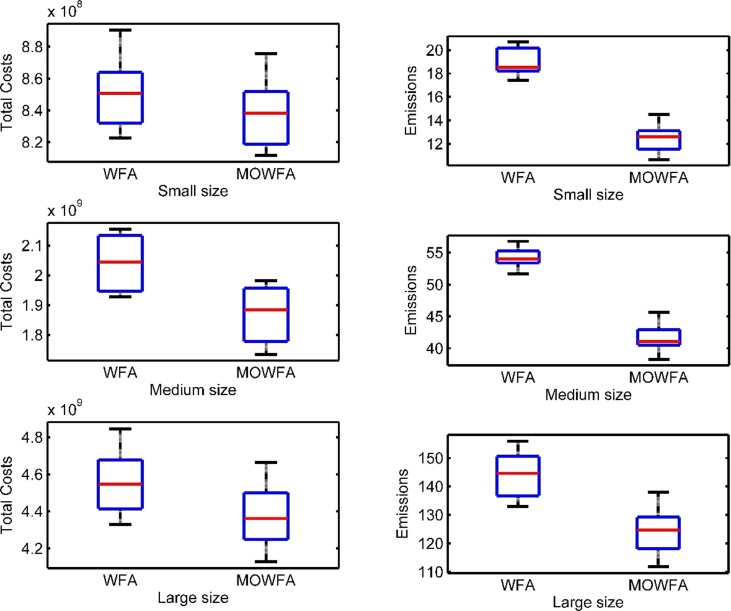

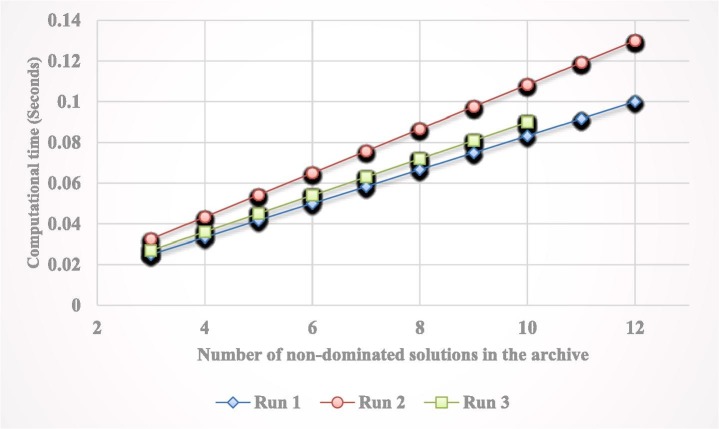

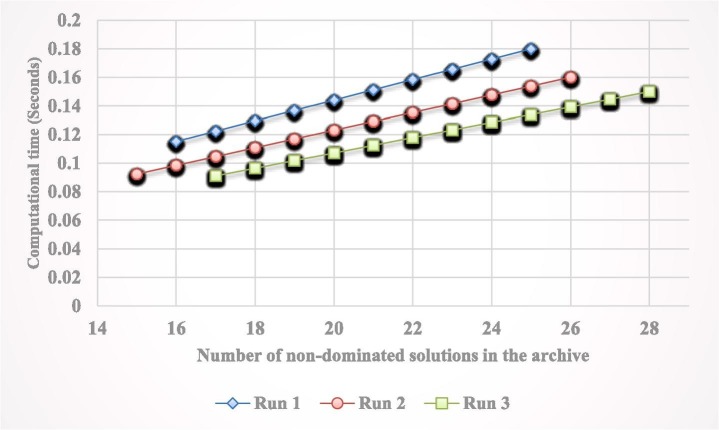

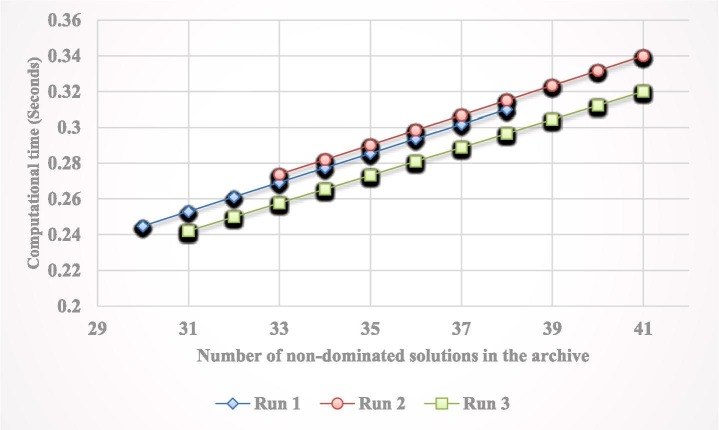

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 detail the computational results of the MOWFA, MOICA, and MOSA in terms of the ER, SM, and MS metrics. Each algorithm has been run for ten times and the average of the obtained values have been reported in these tables. According to the obtained results, the MOWFA has better convergence than the MOICA and MOSA since the MOWFA acquired fewer ER values. Regarding the uniformity of non-dominated solutions obtained by these three methods, it is inferred that the MOWFA outperformed the other methods with respect to the SM metric. Comparing the MS values indicates that the MOWFA has behaved better in producing more diverse solutions than other methods. The performances of algorithms have been compared in terms of their average computational times in Fig. 10, Fig. 11 . These figures show that the MOSA has the least CPU times in finding one solution (ATO metric) and all solutions (ATA metric). The MOWFA is slower than other methods due to the local search strategies embedded in this algorithm.

Table 5.

Comparison of algorithms in terms of ER, SM, and MS metrics for small size problems.

| Problems |

ER |

SM |

MS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | |

| 1 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 1.68 | 5.49 | 4.09 | 0.77 | 0.59 | 0.46 |

| 2 | 0.36 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 1.49 | 4.28 | 6.10 | 0.62 | 0.42 | 0.31 |

| 3 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 5.78 | 9.74 | 9.52 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.62 |

| 4 | 0.37 | 0.57 | 0.76 | 8.01 | 12.08 | 11.66 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 0.68 |

| 5 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.66 | 9.41 | 13.65 | 11.84 | 0.80 | 0.57 | 0.45 |

| 6 | 0.04 | 0.28 | 0.44 | 2.17 | 5.52 | 6.73 | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.46 |

| 7 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 6.12 | 8.37 | 9.99 | 0.74 | 0.55 | 0.41 |

| 8 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.53 | 5.22 | 7.91 | 8.27 | 0.96 | 0.73 | 0.63 |

| 9 | 0.38 | 0.51 | 0.69 | 1.11 | 5.85 | 4.65 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.44 |

| 10 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 0.76 | 4.03 | 6.49 | 7.24 | 0.64 | 0.46 | 0.32 |

| 11 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 0.43 | 2.46 | 6.94 | 4.69 | 0.91 | 0.67 | 0.56 |

| 12 | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.74 | 8.15 | 11.77 | 10.87 | 0.76 | 0.52 | 0.43 |

| 13 | 0.38 | 0.61 | 0.82 | 3.80 | 8.79 | 6.17 | 0.70 | 0.49 | 0.37 |

| 14 | 0.19 | 0.33 | 0.49 | 5.76 | 7.99 | 8.31 | 0.76 | 0.55 | 0.45 |

| 15 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.74 | 2.49 | 5.82 | 5.21 | 0.64 | 0.43 | 0.31 |

| Average | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 4.51 | 8.05 | 7.69 | 0.78 | 0.57 | 0.46 |

Table 6.

Comparison of algorithms in terms of ER, SM, and MS metrics for medium size problems.

| Problems |

ER |

SM |

MS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | |

| 16 | 0.31 | 0.52 | 0.75 | 1.54 | 6.81 | 3.93 | 0.52 | 0.30 | 0.16 |

| 17 | 0.17 | 0.57 | 0.80 | 7.14 | 12.30 | 9.00 | 0.78 | 0.52 | 0.38 |

| 18 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 1.38 | 8.51 | 6.46 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.58 |

| 19 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.66 | 1.64 | 5.06 | 0.11 | 0.83 | 0.60 | 0.48 |

| 20 | 0.06 | 0.73 | 0.96 | 5.69 | 9.36 | 6.86 | 0.60 | 0.34 | 0.21 |

| 21 | 0.11 | 0.27 | 0.48 | 1.87 | 5.74 | 3.42 | 0.68 | 0.46 | 0.36 |

| 22 | 0.18 | 0.68 | 0.89 | 8.36 | 13.32 | 10.20 | 0.73 | 0.50 | 0.38 |

| 23 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.92 | 8.36 | 15.51 | 12.92 | 0.99 | 0.73 | 0.61 |

| 24 | 0.18 | 0.63 | 0.83 | 7.50 | 14.52 | 11.05 | 0.58 | 0.35 | 0.24 |

| 25 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 0.48 | 2.35 | 5.65 | 2.63 | 0.93 | 0.65 | 0.54 |

| 26 | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.54 | 6.94 | 11.93 | 7.08 | 0.82 | 0.52 | 0.40 |

| 27 | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.66 | 5.67 | 11.30 | 6.54 | 0.69 | 0.42 | 0.31 |

| 28 | 0.26 | 0.57 | 0.81 | 9.76 | 14.84 | 12.68 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.23 |

| 29 | 0.38 | 0.29 | 0.52 | 6.84 | 13.13 | 8.91 | 0.71 | 0.46 | 0.33 |

| 30 | 0.10 | 0.61 | 0.83 | 8.20 | 14.34 | 11.54 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 0.40 |

| Average | 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.72 | 5.55 | 10.82 | 7.56 | 0.74 | 0.50 | 0.37 |

Table 7.

Comparison of algorithms in terms of ER, SM, and MS metrics for large size problems.

| Problems |

ER |

SM |

MS |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | MOWFA | MOICA | MOSA | |

| 31 | 0.27 | 0.61 | 0.84 | 2.35 | 7.56 | 6.21 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.40 |

| 32 | 0.09 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 5.43 | 11.48 | 9.15 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.34 |

| 33 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.89 | 3.35 | 7.16 | 5.50 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.55 |

| 34 | 0.11 | 0.44 | 0.64 | 2.86 | 10.46 | 7.66 | 0.77 | 0.52 | 0.42 |

| 35 | 0.41 | 0.73 | 0.92 | 3.44 | 8.86 | 7.62 | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.37 |

| 36 | 0.12 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 3.03 | 10.22 | 7.24 | 0.67 | 0.36 | 0.24 |

| 37 | 0.34 | 0.68 | 0.91 | 3.32 | 7.59 | 5.51 | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.42 |

| 38 | 0.08 | 0.39 | 0.64 | 2.30 | 9.29 | 6.88 | 0.67 | 0.46 | 0.32 |

| 39 | 0.13 | 0.47 | 0.57 | 6.45 | 14.25 | 11.25 | 0.83 | 0.53 | 0.42 |

| 40 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.62 | 3.97 | 10.51 | 8.93 | 0.92 | 0.63 | 0.52 |

| 41 | 0.26 | 0.59 | 0.78 | 5.77 | 12.18 | 10.35 | 0.87 | 0.59 | 0.46 |

| 42 | 0.31 | 0.65 | 0.90 | 6.87 | 13.15 | 11.22 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 0.25 |

| 43 | 0.25 | 0.58 | 0.76 | 5.49 | 11.56 | 9.03 | 0.68 | 0.37 | 0.23 |

| 44 | 0.19 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 5.75 | 10.92 | 8.28 | 0.92 | 0.60 | 0.46 |

| 45 | 0.29 | 0.60 | 0.82 | 5.12 | 9.51 | 8.31 | 0.97 | 0.72 | 0.58 |

| Average | 0.22 | 0.55 | 0.75 | 4.37 | 10.31 | 8.21 | 0.80 | 0.53 | 0.40 |

Fig. 10.

Comparison of algorithms in terms of the ATA.

Fig. 11.

Comparison of algorithms in terms of the ATO.

6.4.1. Statistical comparisons

The performances of the three algorithms have been statistically evaluated as well. The statistical comparisons have been implemented using the 2-sample t-test and the following hypotheses. These comparisons have been made in terms of each performance metric at a 95% confidence level. The null hypothesis () assumes the equality of the means of methods regarding a performance measure which implies that there is no significant difference between them. The alternative hypothesis () presents the opposite assumption. Thus, the null hypothesis () is rejected if the p-value is less than 5% (Zandieh et al., 2019).

| : | The means of a performance measure value obtained by the algorithms are not significantly different. |

|---|---|

| : | The means of a performance measure value obtained by the algorithms are significantly different. |

Each algorithm has solved the test problems for ten times. The following sub-sections discuss the statistical comparisons between the algorithms in terms of the performance metrics mentioned in Section 5.3.

-

•

MOWFA versus MOICA

Table 8 compares the performances of the MOWFA and MOICA. Results reported in Table 8 indicate that the p-values are less than 5% for the ER, SM, and MS performance measures. Hence, the null hypotheses () for these metrics are rejected which means that the superiority of the MOWFA is evident over the MOICA. On the other hand, the p-values for the ATO and ATA metrics are not less than 5%. Therefore, it can be concluded that the MOWFA is not significantly slower than the MOICA.

-

•

MOWFA versus MOSA

Table 8.

Statistical test results for the MOWFA vs. MOICA.

| Problem size | Performance measure | Lower bound | Upper bound | p-Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | ATO | −0.01 | 0.15 | 0.10 | is not rejected. |

| ATA | −0.20 | 13.13 | 0.057 | is not rejected. | |

| ER | −0.28 | −0.08 | 7.03e−004 | is rejected. | |

| SM | −5.55 | −1.51 | 0.0013 | is rejected. | |

| MS | 0.12 | 0.29 | 2.22e−005 | is rejected. | |

| Medium | ATO | 0.003 | 0.45 | 0.04 | is rejected. |

| ATA | −18.96 | 32.32 | 0.59 | is not rejected. | |

| ER | −0.39 | −0.18 | 3.85e−006 | is rejected. | |

| SM | −7.76 | −2.77 | 1.74e−004 | is rejected. | |

| MS | 0.14 | 0.34 | 3.69e−005 | is rejected. | |

| Large | ATO | −0.03 | 0.87 | 0.07 | is not rejected. |

| ATA | −42.46 | 58.09 | 0.75 | is not rejected. | |

| ER | −0.41 | −0.24 | 8.12e−009 | is rejected. | |

| SM | −7.30 | −4.59 | 9.81e−010 | is rejected. | |

| MS | 0.19 | 0.35 | 2.70e−007 | is rejected. |

The MOWFA and MOSA have been compared statistically, and the results have been summarized in Table 9 . Based on the outputs, the p-values are less than 5% for most of the metrics. Therefore, the null hypotheses for these measures are rejected. This means that the MOWFA significantly overcomes the MOSA regarding the ER, SM, and MS. Moreover, it can be inferred that the MOWFA is significantly slower than the MOSA.

Table 9.

Statistical test results for the MOWFA vs. MOSA.

| Problem size | Performance measure | Lower bound | Upper bound | p-Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | ATO | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.001 | is rejected. |

| ATA | 3.30 | 16.30 | 0.004 | is rejected. | |

| ER | −0.46 | −0.25 | 1.023e−007 | is rejected. | |

| SM | −5.14 | −1.20 | 0.0026 | is rejected. | |

| MS | 0.23 | 0.41 | 2.78e−008 | is rejected. | |

| Medium | ATO | 0.15 | 0.61 | 0.00 | is rejected. |

| ATA | −14.20 | 36.66 | 0.37 | is not rejected. | |

| ER | −0.61 | −0.41 | 6.62e−011 | is rejected. | |

| SM | −4.57 | 0.56 | 0.12 | is not rejected. | |

| MS | 0.26 | 0.47 | 5.52e−008 | is rejected. | |

| Large | ATO | 0.33 | 1.22 | 0.00 | is rejected. |

| ATA | −37.83 | 62.38 | 0.61 | is not rejected. | |

| ER | −0.62 | −0.44 | 6.86e−013 | is rejected. | |

| SM | −5.10 | −2.57 | 9.94e−007 | is rejected. | |

| MS | 0.31 | 0.48 | 1.49e−010 | is rejected. |

6.4.2. Ranking solution approaches

In the following, we used a two-phase approach based on the Multi-Attribute Decision Making (MADM) methods to rank the algorithms in terms of their results. The goal of this approach is to find the most efficient algorithm in solving test problems. In this respect, the algorithms and performance evaluation metrics are considered as the alternatives and criteria, respectively. In the first phase of this approach, the weights of the criteria are calculated via the Best-Worst Method (BWM), and the second phase involves prioritizing the algorithms by means of the Simple Additive Weighting (SAW) method. This approach is called the BWM-SAW that has been described in Algorithm 4.

| Algorithm 4: BWM-SAW method | ||

|---|---|---|

| Notations: | ||

| NC | Number of criteria (. | |

| NA | Number of algorithms (alternatives) (). | |

| BTO | Best-To-Others vector. | |

| OTW | Others-To-Worst vector. | |

| Optimal weight of the criterion (. | ||

| Consistency value. | ||

| Decision matrix (Rows and columns represent the algorithms and criteria, respectively). | ||

| The element on the row and column of the decision matrix. | ||

| Normalized element on the row and column. | ||

| Ultimate score of the algorithm. | ||

| Phase 1 (BWM) | 1. | Determine the most important (the best) criterion. |

| 2. | Determine the least important (the worst) criterion. | |

| 3. | Use a number on the interval to show the preference of the most important criterion over the other criteria. Hence, the Best-To-Others vector (BTO) is formed as , where denotes the preference of the best criterion B over the criterion. | |