Abstract

Severe/critical cases account for 18–20% of all novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients, but their mortality rate can be up to 61.5%. Furthermore, all deceased patients were severe/critical cases. The main reasons for the high mortality of severe/critical patients are advanced age (>60 years old) and combined underlying diseases. Elderly patients with comorbidities show decreased organ function and low compensation for damage such as hypoxia and inflammation, which accelerates disease progression. The lung is the main target organ attacked by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) while immune organs, liver, blood vessels and other organs are damaged to varying degrees. Liver volume is increased, and mild active inflammation and focal necrosis are observed in the portal area. Virus particles have also been detected in liver cells. Therefore, multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) and individualized treatment plans, accurate prediction of disease progression and timely interventions are vital to effectively reduce mortality. Specifically, a “multidisciplinary three-dimensional management, individualized comprehensive plan” should be implemented. The treatment plan complies with three principles, namely, multidisciplinary management of patients, individualized diagnosis and treatment plans, and timely monitoring and intervention of disease. MDT members are mainly physicians from critical medicine, infection and respiratory disciplines, but also include cardiovascular, kidney, endocrine, digestion, nerve, nutrition, rehabilitation, psychology and specialty care. According to a patient's specific disease condition, an individualized diagnosis and treatment plan is formulated (one plan for one patient). While selecting individualized antiviral, anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory treatment, we also strengthen nutritional support, psychological intervention, comprehensive rehabilitation and timely and full-course intervention to develop overall and special nursing plans. In response to the rapid progression of severe/critical patients, MDT members need to establish a three-dimensional management model with close observation and timely evaluation. The MDT should make rounds of the quarantine wards both morning and night, and of critical patient wards nightly, to implement “round-the-clock rounds management”, to accurately predict disease progression, perform the quick intervention and prevent rapid deterioration of the patient. Our MDT has cumulatively treated 77 severe/critical COVID-19 cases, including 62 (80.5%) severe cases and 15 (19.5%) critical cases, with an average age of 63.8 years. Fifty-three (68.8%) cases presented with more than one underlying disease and 65 (84.4%) severe cases recovered from COVID-19. The average hospital stay of severe/critical cases was 22 days, and the mortality rate was 2.6%, both of which were significantly lower than the 30–40 days and 49.0–61.5%, respectively, reported in the literature. Therefore, a multidisciplinary, three-dimensional and individualized comprehensive treatment plan can effectively reduce the mortality rate of severe/critical COVID-19 and improve the cure rate.

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), Severe COVID-19, Critical COVID-19, Treatment, Multidisciplinary teams

1. Introduction

As of 3 April 2020, 1,014,868 people in more than 200 countries around the world have been diagnosed with novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), with a total of 52,981 deaths. The COVID-19 epidemic was declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization. Among COVID-19 patients, mild/ordinary cases account for 80.9%, while severe/critical cases account for 18.5%, with a mortality rate as high as 49.0–61.5%.1 , 2 Therefore, it is crucial to strengthen the treatment of severe/critical patients to enhance the clinical cure rate and reduce mortality. Because of the difficulties in the clinical treatment of severe/critical COVID-19 patients, and consistent with the National Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia (Trial Edition 7) and Diagnosis and Treatment of Severe/Critical Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Trial Edition 3) issued by the National Health Commission of China,3 , 4 we have summarized “multidisciplinary, three-dimensional and individualized comprehensive treatment” for severe/critical patients in combination with our own experiences of diagnosis and treatment. This treatment approach has achieved good effects and significantly reduced the mortality rate while greatly improving the cure rate in severe/critical COVID-19 patients.

2. Clinicopathological characteristics of severe/critical COVID-19

The respiratory system is the main target organ attacked by SARS-CoV-2. The pathophysiological characteristics include diffuse alveolar injury with fibrous mucinous exudation and retention of mucous secretions in the small airways, hyaline membrane formation in the alveolar spaces,5 , 6 lung interstitial fibrosis and lung consolidation, atrophy of alveolar epithelium and cytoplasmic necrotizing bronchitis, along with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and pulmonary hemorrhagic infarction in some cases (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Pathological features of COVID-19.

| Tissue/Organ | Generally appearance | Optical microscopea |

Electron microscope Immunohistochemistry Viral nucleic acid test | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early stage | 2nd to 3rd week of illness | 4th week of illness | Disease duration >4 weeks | |||||

| Respiratory system |

(Gross observation of autopsy systems after death on day 15 of the illness in one critical COVID-19 patient and whole lung tissue in one case of lung transplantation) (i) Patchy grayish-white inflammatory foci and dark red or dark black diffuse foci of congestion and hemorrhage in both lungs, with mixed congestion, hemorrhage and inflammatory exudation in the lesions, some with hemorrhagic necrosis, with heavy inflammatory foci in the marginal zone of the lung (ii) Toughness, loss of intrinsic spongy feeling of the lung, bronzed lung changes (iii) Massive retention of mucoid secretions: large amounts of grayish-white viscous secretions are seen spilling out of the alveoli in the section; frothy white mucus or jelly-like mucus is seen adhering to the tracheal lumen, covered by hemorrhagic exudates (iv) Fibrous strands are visible on the cut surface |

(Microscopic observation of lobectomy specimens in 2 patients with lung cancer and COVID-19) (i) Exudation: exudation of proteins and fibers from the alveolar cavity; widened alveolar septa, vascular congestion, mild inflammatory cell infiltration and multinucleated giant cell formation (ii) With focal hyperplasia: formation of granulomatous nodules from fibrin, inflammatory cells, and multinucleated giant cells; diffuse thickening of alveolar walls and proliferation of interstitial fibroblasts (iii) Viral inclusion bodies: suspected viral inclusion bodies found |

(Post-mortem autopsy and lung puncture tissue samples after the death of one COVID-19 patient on day 14 and another on day 15 of the disease course) Diffuse alveolar injury with fibrous mucinous effusion: (i) Transparent film formation (ii) Pulmonary edema (iii) Inflammatory damage to alveolar epithelial cells (iv) Single nucleus inflammatory cell infiltration (v) Atypically enlarged alveolar cells with multinucleated giant cells and viral cytopathic-like changes in the alveolar cavity (vi) Retention of mucus secretions in small airways |

(Pulmonary puncture specimens after death on days 22 and 23 of the disease course in 2 patients with COVID-19, respectively) (i) Transparent film formation (ii) Vascular congestion: widening of alveolar interval and vascular congestion (iii) Inflammatory cell infiltrate: small amounts of single nucleated inflammatory cells and focal lymphocyte infiltrate (iv) Proliferation: type II alveolar epithelium and interalveolar fibroplasia |

(Pulmonary puncture specimen from a patient with COVID-19 who died on day 52 of the disease course) (i) Transparent film residue: some alveoli have residual hyaline membranes (ii) Widening of the alveolar septum: interstitial edema, fibrous tissue hyperplasia of the alveolar septum, infiltration of single nucleated inflammatory cells; occasionally small blood vessels are seen cellulose-like necrosis (iii) Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage: massive intra-alveolar hemorrhage and intra-alveolar fibrin globule formation (iv) Combined with bacterial infection: large infiltration of neutrophils in the alveoli leading to solid lesions |

(i) Electron microscopy: coronavirus particles can be seen in the cytoplasm of lower bronchial mucosal epithelium and type II alveolar epithelial cells (ii) Immunohistochemistry: partial alveolar epithelium and macrophages positive for novel coronavirus antigens, immunopositive cells are expressed centrally in the lung interstitium and near blood vessels (iii) Tissue's COVID-19 R T-PCR: positive nucleic acid test in lung tissue |

3,6,7,12 |

|

| Summary: in the early stage, exudative lesions were mainly associated with focal hyperplasia. The severe phase is characterized by diffuse alveolar injury with fibrous mucus exudate and retention of mucus secretions in the small airways, and inflammatory cells are mainly activated aggregated macrophages. As the disease progresses, type II alveolar epithelium and alveolar septal fibroplasia gradually becomes evident, with massive interstitial fibrosis accompanied by vasculopathy; diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and concomitant bacterial infection may occur. |

||||||||

| Extra-pulmonary organs: | ||||||||

| Spleen | Spleen shrinkage | The number of lymphocytes is significantly reduced, with focal hemorrhage and necrosis, and macrophage proliferation and phagocytosis are seen | Immunohistochemistry: CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells were decreased | 3 | ||||

| Lymph nodes | Lymphocytes are few and necrotic | 3 | ||||||

| Bone marrow | Decrease in the number of cells in the erythroid, leukocyte, and megakaryocyte lines | 3 | ||||||

| Heart and blood vessels | The myocardial sections were grayish-red fish-like and shiny (the underlying disease was coronary atherosclerotic heart disease and the effect of the underlying disease could not be excluded) | (i) Local myocardial bundles are irregular in morphology and deeply stained in the cytoplasm. Monocyte inflammatory infiltrate is seen in a small amount of myocardial interstitium (ii) Partial endothelial detachment, endotheliitis and thrombosis |

Tissue's COVID-19 R T-PCR: positive nucleic acid test in myocardial tissue | 3,5, 6, 7 | ||||

| Liver and gallbladder | Liver volume is enlarged and dark red and the gallbladder is highly inflated | (i) The structure of hepatic lobules was largely preserved, and mild active inflammation 5 and focal necrosis could be seen in the confluence region (ii) Mild steatosis of hepatocytes, focal necrosis with neutrophil infiltration (iii) Some of the sinuses are dilated or congested (iv) Vascular microthrombosis with focal necrosis around the central vein |

(i) Electron microscopy: typical novel coronavirus particles can be observed in hepatocytes. (ii) Tissue's COVID-19 R T-PCR:positive nucleic acid test in liver tissue |

3,5,7,8,12 | ||||

| Renal | Protein exudate is seen in the glomerular capsule lumen, and the tubular epithelium is denuded and detached, with a clear tubular pattern. Interstitial congestion with microthrombi and focal fibrosis visible | 3 | ||||||

| Nerve system | Mild subcranial edema, cerebral edema | Congestion and edema of brain tissue, partial neuronal degeneration | Novel coronavirus sequence was confirmed in cerebrospinal fluid by gene sequencing in Beijing Ditan Hospital | 3,6 | ||||

| Alimentary tract | The gastric mucosa is dark red with a few bleeding spots. The intestine is normal in color, with segmental dilatation of the small intestine interspersed with narrowing |

Different degrees of degeneration, necrosis and detachment of the mucosal epithelium of the esophagus, stomach and intestine | 3,6 | |||||

| Serous cavity | Light yellow clear fluid can be seen in the pleural cavity, pericardium and abdominal cavity with a small to medium amount. Severe pleural adhesion can be seen with bacterial infection | 6 | ||||||

a Four time periods of optical microscope observation were only shown in the respiratory system. Abbreviations: COVID-19, novel coronavirus disease 2019; RT-PCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction.

In many patients, the immune organs are also affected. Peripheral blood flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry of spleen and lymph nodes in COVID-19 patients show a significant decrease in CD4+ T and CD8+ T lymphocytes. Almost no inflammatory hyperplasia in lymph nodes or spleen is observed and the lymphocyte count and activation markers are decreased dramatically in cases succumbing to disease, suggesting that fatal cases are in an immunodepleted state (Table 1).4 , 5

Liver damage is also observed in some severe/critical COVID-19 patients, mainly manifesting as increased transaminase, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and decreased serum albumin, without significant increases in bilirubin, gamma glutamyl transferase and alkaline phosphatase. The pathological manifestations include increased liver volume,3 along with mild active inflammation and focal necrosis in the portal area, and microvascular thrombosis and focal necrosis around the central vein.5 , 7 SARS-CoV-2 particles in liver cells have also been identified in liver sections under electron microscopy (Table 1).8

Previous studies have shown that the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) to invade cells,9 and ACE2 is expressed in multiple organs such as ileum, heart, kidney, lung, testis and the central nervous system. Clinical data from severe COVID-19 patients indicate that extra-pulmonary organs including the heart and kidneys suffer damage during COVID-19. However, according to pathology upon autopsy of deceased cases, the damage to extra-pulmonary organs is relatively mild; therefore, the main target organ of SARS-CoV-2 is the lungs (Table 1).3, 4, 5 , 10, 11, 12

3. Difficulties in clinical treatment of severe/critical patients

A high proportion of severe/critical COVID-19 patients are elderly with underlying comorbidities. According to the CDC data, 81% of COVID-19 deaths occur in elderly patients (>60 years old) and the mortality rate is higher with increased age.1 This is mainly related to the decline in organ function, low compensation for damage such as hypoxia and inflammation, and poor self-living ability. Elderly COVID-19 patients often suffer from multiple combined underlying diseases, increasing the mortality rate 5–10 fold. In particular, for patients with cardiovascular diseases, the risk of death is increased over 11 times that of patients without underlying comorbidities.1 The range of underlying conditions increases the challenge faced by physicians to provide effective treatment for severe/critical COVID-19 patients.

Viral infection and inflammation-related injuries to extra-pulmonary organs are commonly observed in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 can invade the heart, kidneys and intestines in addition to the lungs, resulting in damage to a variety of extra-pulmonary organs and new organ dysfunctions. Such damage exacerbates underlying diseases to further aggravate damage to the organs and increase the difficulty of treatment.

Treatment can be further complicated as lung injury and imaging results are not always consistent with patients’ subjective symptoms. Some patients have serious imaging findings, but their respiratory symptoms are mild. Clinically, imaging cannot accurately predict the severity or rapid progression of disease, which may lead to adverse consequences.

Low immunity is another challenge to effective treatment. Low immunity is often multifaceted: first, as described above, a high proportion of severe/critical patients are elderly people who often suffer from multiple underlying diseases, and so they have lower immunity than younger, healthy individuals; second, severe/critical patients often have high consumption and poor nutritional status; third, hypoxia, inflammation and intestinal infections of COVID-19 impair the digestive functions of patients, and the resulting insufficient nutrient availability that further reduces immune function.

Severe/critical COVID-19 patients often have differing levels of psychological problems stemming from a sense of dying caused by hypoxia, fear of disease, the quarantine environment, difficulty in verbal communication and various other stress events (such as family-clustering infections, death of loved ones).

Because COVID-19 patients require an extended period of bedrest, their lung function impairment and muscle atrophy can be very obvious. It is very important to implement related evaluation and rehabilitation therapy to ensure that recovery is as full as possible.

Finally, the quarantine ward environment presents its own challenges for treatment of patients. In quarantine wards, medical staff are in a strict protection environment, making it difficult to perform routine physical examinations, disease condition observations and medical operations. In addition, given the elderly nature of many severe/critical patients, some medical advice may not be understood or implemented properly.

4. Multidisciplinary, three-dimensional and individualized comprehensive treatment pattern for severe/critical patients

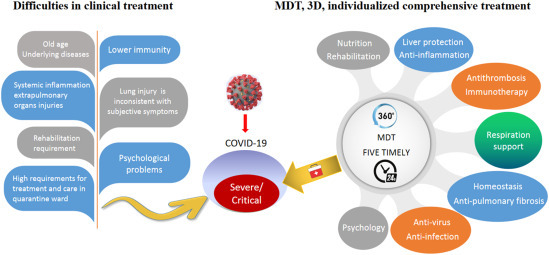

The hypoxic inflammation caused by severe/critical COVID-19 and underlying diseases promotes rapid disease progression, leading to a high mortality rate. In view of the difficulties in clinical treatment of severe/critical patients, a “multidisciplinary, three-dimensional management, individualized comprehensive plan” treatment pattern should be implemented to enhance the cure rate and reduce mortality.

4.1. Establishing a multidisciplinary team (MDT)

Patients with severe/critical COVID-19 have many extra-pulmonary injuries and underlying diseases, so an MDT should be established to achieve collaborative treatment. The MDT should be mainly composed of physicians and nurses specializing in severe illness, infection and respiratory medicine, together with specialists and nurses in the heart, kidney, endocrine, digestion, nerve, nutrition, rehabilitation and psychology disciplines. The MDT should facilitate timely discussion of the condition of severe/critical COVID-19 patients so as to quickly develop the most reasonable individualized diagnosis and treatment program, taking into account underlying comorbidities.

4.2. Multidisciplinary and three-dimensional patient management pattern

A multi-disciplinary management model is tailored to the combined underlying disease profile of each patient. A “special disease responsibility system” with the specialist of the most life-threatening combined disease as the chief expert is implemented for 24 h management. A multi-channel, multi-disciplinary, three-dimensional consultation mechanism is formed relying on various resources, so that common problems are resolved by the team and difficult problems are resolved by remote consultation and discussion in the hospital.

According to the specific conditions in each patient, we developed a precision treatment program of “one plan for one patient”, based on guidelines. We have a daily MDT discussion and update the program. Relying on our team's strengths, comprehensive interventions such as nutrition support, psychological intervention and rehabilitation training are implemented, which effectively improves the cure rate of severe/critical patients. We have adopted the following key measures. First, various oxygen therapy methods are applied to quickly alleviate hypoxia and provide a basis for other treatments. Second, we adhere to the principle of multidisciplinary diagnosis and treatment, simultaneously treating the pneumonia and serious underlying diseases to prevent them from exacerbating each other. Third, we implement individualized anti-virus, anti-infection, and anti-inflammatory/immunotherapy. We clarify the applicable groups of various antiviral drugs, strictly follow the indications for antibiotics, and select the anti-inflammatory/immunotherapy according to the patient's immune status and inflammation indicators, while preventing drug-related adverse reactions and multidrug interactions to avoid secondary damage. Fourth, we implement prompt, individual and full nutrition support, psychological intervention and comprehensive rehabilitation. Nutrition experts perform evaluations, determine an individualized nutrient supplement plan and run through the whole process. The patients' psychological needs are identified to eliminate various concerns and provide individualized emotional support, sleep education and a small amount of drugs. While ensuring safety, individualized rehabilitation training programs should be formulated to improve the general conditions and respiratory functions of elderly severe/critical patients. Fifth, we develop an overall care plan based on “one plan for one patient”. By integrating specialist nursing methods in medicine, nutrition, psychology, and rehabilitation for severe/critical cases, we implement special care for special patients, to ensure proper disease observation, drug therapy, nutrition support and rehabilitation training, providing various conveniences for patients in a cordial and sincere manner, listen to patients' needs and create a warm and harmonious humanistic nursing atmosphere.

5. Implementation of individualized comprehensive treatment for severe/critical patients

5.1. Timely observation, accurate prognosis and intervention in critical patients

Severe/critical patients often present with a variety of underlying diseases, have low immunity, severe lung damage, rapid disease progression and inconsistency between imaging severity and subjective symptoms. It is crucial to evaluate the severity of disease, judge the disease trend, make early interventions and prevent disease progression to reduce COVID-19-induced mortality. Thus, we should strive to follow the “five timely”: timely observation, timely examination, timely consultation, timely early warning and timely treatment. First, timely observation: observe the respiratory oxygenation and vital organ functions; second, timely examination: examine the functions of the lungs and other organs and evaluate them; third, timely consultation: seek multi-level and multi-disciplinary support; fourth, timely early warning: give timely early warning in case of disease aggravation and poor prognosis; fifth, timely treatment: provide timely treatment for critical conditions, disease progression and other urgent problems.

5.1.1. Dynamic clinical observation: early warning signs

Astute observation of the symptoms and signs in COVID-19 patients is vital. Because of the limitations in quarantine ward conditions, disease condition observations of severe cases include several aspects. Observation of the patients’ basic condition, including age greater than 65 years, combined with multiple organ damage and underlying diseases is key, as these are high-risk factors for death.1 , 13 Any new or altered development of mental depression, laziness to speak, irritability and consciousness change, etc., indicate severe disease or disease progression. Any changes to vital signs, including persistent fever (for example, >38 °C) or increased body temperature, heart rate greater than 100 beats/min continuously or faster than before, blood pressure lower than 90/60 mmHg or progressive decline, or mean arterial pressure lower than 70 mmHg, suggest disease progression or even shock. Similarly, respiratory symptoms must be accurately observed. Aggravated coughing, shortness of breath, decreased activity tolerance, respiratory rate greater than 30 times/min continuously or further aggravation, or blood oxygen saturation lower than 93% suggest severe disease or disease progression. During oxygen therapy, it is necessary to monitor the blood oxygen saturation and maintain SpO2 ≥95%. Otherwise, arterial blood gas analysis needs to be performed as soon as possible, and according to the oxygenation index (PaO2/FiO2), the respiratory support treatment method can be adjusted. If the patient meets the criteria for invasive mechanical ventilation treatment, intubation should be performed urgently; delayed tracheal intubation will lead to poor clinical outcome. Digestive tract symptoms are also indicative of altered disease status. Loss of appetite or refusal to eat, combined with abdominal bloating and discomfort suggest possible changes in disease conditions. Continuously decreased urine volume or no urine, evident dehydration and heart rate sudden drop in below 60 beats/min and deep respiration suggest abnormal renal function or insufficient intake, high potassium or acidosis, which should be treated urgently.

In some severe/critical patients, although their oxygenation index is less than 200 mmHg and CT imaging indicates the progression of lung lesions, the patient's subjective symptoms remain mild and so can be easily ignored clinically. Therefore, comprehensive assessment should be performed based on the patient's heart rate, respiration rate, oxygenation index, imaging and other laboratory indicators, to identify disease condition changes early and effective interventions should be taken to avoid sudden worsening of disease.

5.1.2. Laboratory-based prognostic indicators: early warning signs

Early identification of changes in white blood cell counts is of great importance in severe/critical COVID-19 patients. Peripheral blood lymphocyte count gradually decreases to (0.3–0.4) × 109/L.14 Absolute lymphocyte count is positively associated with the severity of disease, and continuous decline of lymphocytes is a sign of poor prognosis. COVID-19 patients often show increased neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (NRL), which was more pronounced in patients who ultimately succumbed to disease. When the NRL is ≥ 3.13, patients should be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) quickly.15 If the CD4/CD8 count decreases, the neutrophil/CD8+ T ratio (N8R) increases and the CD4+ T lymphocyte count falls to <0.25 × 109/L, it indicates a worsening of disease and the treatment plan should be urgently adjusted, such as by administering immunopotentiation therapy.16 Decreased hemoglobin indicates that the patient has poor nutritional status and decreased tissue tolerance to hypoxia, while a rapid decrease of hemoglobin in a short time may indicate that the patient has combined hemolysis (for example, hemolysis caused by antiviral drugs) or gastrointestinal bleeding, etc., and timely intervention should be performed.

Cytokine storm is an important cause of death in COVID-19, so early identification of elevated inflammatory cytokine levels is vital. Severe/critical patients often have progressively increased inflammatory cytokines in the peripheral blood. Therefore, inflammatory markers should be closely monitored to assess the intensity of the inflammatory response. Common cytokines include C-reactive protein, of which a concentration of >34 mg/L is a high risk factor for death, plasma interleukin (IL)-2, IL-7, IL-10, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, interferon-gamma inducible protein 10, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, macrophage inflammatory protein-1 -alpha and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Severe/critical patients often have higher levels of these markers.17 IL-6 is a marker of cytokine cascade activation that can promote myocardial dysfunction and lead to serious conditions such as blood vessel leakage, activation of complement and diffusive intravascular coagulation caused by the coagulation cascade. Therefore, cytokine storm may occur in patients with significantly elevated IL-6 in the early onset of disease, indicating that targeted IL-6 antagonistic therapy should be considered.

In terms of virus detection, poor prognosis is indicated by prolonged viral shedding of more than 20 days, detected in nasopharyngeal swabs or alveolar lavage, or virus positivity in serum.13 , 18

Oxygenation index is also an important indicator of prognosis. If a patient's oxygenation index is < 150 mmHg and lasts longer than 12 h, there is a risk of cytokine storm caused by hypoxia. If a patient's oxygenation index is < 80 mmHg, which further worsens under high-flow oxygen inhalation or non-invasive ventilation,2 this further indicates poor prognosis. Similarly, tissue oxygenation indicators such as LDH should also be monitored; poor prognosis is indicated by progressively increasing lactic acid levels, blood lactic acid ≥3 mmol/L lasting more than 48 h and LDH greater than twice the upper limit of normal.

Increased D-dimer is positively correlated with COVID-19 severity. In the case of severe acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), D-dimer can suddenly increase to more than 50 μg/L. However, D-dimer of greater than 1 μg/L is a high risk factor for mortality in severe/critical patients,13 so active interventions should be performed.

Electrolyte disturbances (such as low/high potassium, low/high sodium) and acid-base imbalance (mainly metabolic acidosis, hyperlactacidemia) easily induce arrhythmia and central nervous system disorders while aggravating hypoxia and systemic dysfunctions. Once identified, these symptoms should be treated urgently to prevent poor prognosis.

5.1.3. Imaging: early warning signs

Chest computed tomography (CT) or X-ray is recommended for all high-risk groups with clinical early warning signs, even if they have no obvious respiratory symptoms. These should be repeated regularly, once every 3–5 days. Extensive lung lesions upon admission indicate that the patient is in severe condition. Dynamic CT re-examination showing an increased number of lesions, expanded range and increased ground glass opacity (GGO) density indicates disease progression. If the lesions show an obvious progression >50% within 24–48 h, this also indicates disease progression to critical or severe condition, and active interventions such as adjusting respiratory support and immunomodulation therapy should be performed.

Ultrasound has limited value for the diagnosis of lung lesions, but it is real-time, rapid and simple, especially for patients with poor blood oxygen status or those who cannot undergo CT scan. It has advantages for the evaluation of lung water and pleural effusion. Detection of shred-, tissue-like-, or dynamic bronchial inflation signs and other consolidations at the time of admission by ultrasound indicates severe disease. If dynamic lung ultrasound re-examination shows consolidations or progression of consolidation range, it indicates aggravation of the disease and the clinical treatment program should be urgently adjusted. If extra-pulmonary water is found to increase outside the pulmonary blood vessels (with typical manifestation of diffuse B-line sign found in multiple sites by pulmonary ultrasonography), the fluid balance plan should be adjusted, and the effusion outflow should be increased appropriately. Although pleural effusion is rare, when the lateral diameter of pleural effusion exceeds 3 cm or increases progressively, ultrasound-guided puncture drainage should be performed. Typical myocardial involvement for severe/critical COVID-19 patients is mainly manifested as reduced diffusive or regional wall motion, reduced short-axis shortening fraction. If dynamic ultrasound shows reduced ejection fraction and increased pulmonary vascular resistance, etc., it suggests poor cardiac function, and continuous cardiac function testing should be performed to control the volume load. When required based on disease condition, central venous catheter can be indwelled under ultrasound guidance.

5.1.4. Timely intervention

When there are signs of disease progression, interventions should be carried out in a timely and effective manner, including the following: improve the hypoxia as early as possible; adjust the anti-virus and anti-infection plan urgently; maintain the functions of vital organs throughout the process; actively maintain homeostasis; administer active anti-inflammatory/immunomodulation therapy; provide full supportive treatment; provide comprehensive and flexible emotional support and psychological intervention; strengthen the overall nursing management, ensuring appropriate treatment and observations of the disease conditions with the patient, and give timely communication and feedback.

5.2. Oxygen and respiratory therapies

Patients with severe/critical COVID-19 suffer from different levels of hypoxia and respiratory failure. Unless chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is underlying, patients generally exhibit type I respiratory failure but rarely type II respiratory failure, and so they require different methods of oxygen therapy or respiratory support therapy (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Multidisciplinary, three dimensional and individualized comprehensive treatment pattern for severe/critical COVID-19. MDT and individualized treatment plans, accurate prediction of disease progression and timely interventions are vital to effectively reduce mortality. MDT members are mainly physicians from critical medicine, infection and respiratory disciplines, but also include cardiovascular, kidney, endocrine, digestion, nerve, nutrition, rehabilitation, psychology and specialty care. MDT members need to establish a three-dimensional management model with close observation and timely evaluation and intervention (i.e., “round-the-clock rounds management” and “five timely”). Abbreviations: MDT, multidisciplinary team; COVID-19, novel coronavirus disease 2019.

For hypoxemia patients with PaO2/FiO2 within the range of 200–300 mmHg, a choice between nasal catheter inhalation, mask oxygen therapy or high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC) oxygen therapy can be given, according to the specific situation. For hypoxemia patients with PaO2/FiO2 within the range of 150–200 mmHg, they will first be given HFNC, and if the anoxia has not been alleviated or has worsened in 1–2 h, invasive mechanical ventilation treatment should be performed urgently. For hypoxemia patients with PaO2/FiO2 <150 mmHg, invasive mechanical ventilation should be applied urgently. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) should be evaluated and implemented as quickly as possible when the patient meets conditions specified in the Program for Diagnosis and Treatment of Severe/Critical Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Trial Edition 3).

5.3. Antiviral treatment

Theoretically, the sooner antiviral therapy is administered, the better. However, according to current expert opinions and published clinical study data, no clear first line antiviral drugs have emerged. As a high proportion of severe/critical patients have underlying comorbidities, it is necessary to carefully evaluate gastrointestinal symptoms, eye disease, heart function and total amount of transfusion for selective use when implementing an antiviral drug regimen. Antiviral treatment can thus be adopted after weighing the advantages and disadvantages.

5.4. Anti-infective treatment

Because COVID-19 is a viral disease, antibiotics are ineffective. Furthermore, due to occurrence of few bacterial infections,2 the conventional combined antibiotic treatment is not recommended.3 However, severe/critical patients are susceptible to secondary bacterial or fungal infections because they are generally elderly patients with combined underlying diseases, often with use of immunosuppressive agents and various invasive procedures as well as aspiration pneumonia in infirm patients, etc. For ICU patients or those with invasive ventilation, attention should be paid to ventilator-associated pneumonia and multi-drug-resistant bacterial infections such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae as well as various fungi. Pathogen culture of a variety of body fluid samples should be carried out during empirical treatment, and the treatment program should be adjusted according to the results of microbiological examination.

5.5. Immunotherapy

Convalescent plasma from recovered patients contains specific IgM and IgG antibodies, and IgG antibodies in particular may have a neutralizing effect, which can facilitate virus elimination and promote recovery. Studies from mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan show that convalescent plasma infusion can shorten the hospital stay of SARS patients and rapidly reduce viremia and mortality.19, 20, 21 In a recent study, five ventilator-supported patients with critical COVID-19 were treated with convalescent plasma, three cases were cured and two achieved stable disease, showing efficacy in terms of virus clearance and body temperature recovery.22 Overall, convalescent plasma is understood to be safe, but its efficacy requires further study.

Thymosin α1, a peptide known to enhance cell-mediated immunity, is widely used in immunocompromised or impaired groups. It has also been used in the treatment of SARS. According to clinical experiences reported in the literature,23 COVID-19 patients may also benefit from thymosin.

5.6. Anti-inflammatory treatment

Inflammation storm is an important cause of disease severity in COVID-19 patients, and can lead to ARDS and multiple organ failure.14 , 17 During the treatment of severe/critical COVID-19 patients, it is necessary to closely monitor the dynamic changes in inflammatory cytokines and optimize anti-inflammatory treatment, so as to improve the prognosis of severe/critical COVID-19 patients.

5.7. Antithrombotic therapy

Patients with COVID-19 have systemic inflammatory responses and hypercoagulability, with elevated fibrin, fibrinogen, and D-dimer.24 These increases are particularly common in patients with severe/critical COVID-19 and are associated with poor prognosis.25 Severe/critical COVID-19 is often accompanied by a variety of basic cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, and patients may be bedridden for a long time during hospitalization, all of which exacerbates the adverse consequences caused by hypercoagulability, such as venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, cerebral infarction, etc. Therefore, routine anticoagulation therapy for severe/critical COVID-19 patients is required, and the anticoagulation regimen should be implemented in accordance with the standard regimen for non-COVID-19 patients.26

5.8. Treatment of consolidation and pulmonary fibrosis

According to the CT imaging distribution characteristics and signs of COVID-19, GGO and consolidation of the lungs are the most common imaging characteristics. Up to 46.2% of COVID-19 patients demonstrate GGO and consolidation.27 Such common pulmonary fibrosis changes seriously affect the prognosis in severe/critical patients; therefore, the treatment of lung consolidation and pulmonary fibrosis is of great significance in the recovery of patients.

5.9. Preventing the liver injury

Underlying liver diseases should be actively treated during COVID-19. Liver damage in COVID-19 patients is usually reversible and can heal without any special treatment. Glycyrrhizin preparations and polyene phosphatidylcholine should be selected if alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels are significantly increased, which suggest that immune-mediated cell necrosis and apoptosis are obvious. If cholestasis and jaundice are evident, S-ademetionine or ursodeoxycholic acid should be selected.

5.10. Maintaining homeostasis

Patients with severe/critical COVID-19 are prone to electrolyte disturbances. Common causes include hypoxia, insufficient electrolyte intake in the diet, vomiting, or loss of electrolytes due to excretion. Patients with severe/critical COVID-19 are also prone to respiratory alkalosis and metabolic acidosis, etc. The etiology should be analyzed and symptomatic treatment performed timeously, and when necessary, continuous renal replacement therapy can be considered. The volume of any transfusions given should follow the general principle of fluid therapy. For the elderly, and patients with cardiac dysfunction and tissue edema, the principle of “less fluid” should be followed, to maintain an appropriate negative balance and prevent excessive fluid. Albumin and blood products should be actively supplemented to maintain blood volume and plasma colloid osmotic pressure.

5.11. Nutritional therapy

Appropriate nutritional therapy can meet the needs of severe/critical patients and improve their immune functions.28 By supplementing reasonable nutrients, this approach can reduce the burden on the gastrointestinal tract and heart.3 We used the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 (NRS2002) scale or the Nutrition Risk in Critically ill (NUTRIC) score to assess the nutritional status of patients and found that all patients with severe/critical COVID-19 in our care had varying degrees of malnutrition.29 Therefore, it is necessary to develop an individualized nutritional support plan to accelerate the recovery of patients.

The treatment plan should adhere to the following principles: target energy should be 25–30 kcal/(kg·d); oral enteral nutrition is preferred; different nutritional preparations are selected according to the individual situation of patients; the parenteral nutrition recommended ratios of three major nutrients should be sugars/lipids, 50–70/50–30, and the optimal ratio of non-protein calorie (kcal) to nitrogen (g) is 100:1–150:1.30

5.12. Psychological intervention therapy

Patients with severe/critical COVID-19 suffer the psychological stress of potentially life-threatening illness, often combined with other stressful events, such as the death of a loved one, family clustering infections, social isolation, etc. This patient group, therefore, is under great psychological pressure.31 Studies have shown that active psychological interventions can improve patients' sleep, moods and bad behaviors, which not only improves patients’ immunity,32 , 33 but can also enhance treatment compliance and improve outcome.

5.13. Rehabilitation therapy

Most severe/critical patients have suffered from different degrees of limb dysfunction and respiratory impairment; therefore, they should receive rehabilitation assessment and treatment of related dysfunctions, to reduce subsequent complications.34

6. Conclusions

Severe/critical COVID-19 is a systemic disease that mainly involves the lungs and immune system. Severe/critical patients are mostly elderly with combined underlying diseases, and suffer from a high mortality rate. Our team has cumulatively treated 77 severe/critical COVID-19 cases, including 62 (80.5%) severe cases and 15 (19.5%) critical cases, with an average age of 63.8 years old; 53 (68.8%) cases presented with more than one underlying disease, and 65 (84.4%) severe cases have recovered. The average hospital stay of severe/critical cases was 22 days, and the mortality rate was 2.6% (2/77), which are significantly lower than the 30–40 days and 49.0–61.5%, respectively, reported in the literature. Therefore, our multidisciplinary, three-dimensional and individualized comprehensive treatment pattern has achieved good effects and significantly reduced the mortality rate of severe/critical COVID-19 patients, while greatly improving the cure rate 24.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express great gratitude to all the members of the Wuhan Medical team and colleagues of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University on the front line that battled against COVID-19 and participated in the consultation, treatment and technical support. Thank them for their guidance and help in summarizing the treatment pattern.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFA0104304); National Natural Science Foundation of China (81770648, 81972286); Guangdong Natural Science Foundation Team Project (2015A030312013); Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (201508020262, 201400000001–3).

Footnotes

Edited by Yuxia Jiang, Peiling Zhu and Genshu Wang.

This is the English version of the originally published article in J SUN Yat-sen Univ (Med Sci), which can be found at Medical Panel of Severe/Critical COVID-19,The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. Management of severe/critical novel COVID-19: Recommendations of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University.J SUN Yat-sen Univ(Med Sci). 2020;41:321-338. http://xuebao.sysu.edu.cn/Jweb_yxb/CN/Y2020/V41/I3/321. Editorial Office of Liver Research compile and modify the article.

References

- 1.Epidemiology Working Group for NCIP Epidemic Response, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 2020;41:145–151. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2020.02.003. (in Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang X., Yu Y., Xu J., et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China . 2020-03-04. National Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Novel Coronavirus- Infected-Pneumonia (Trial Edition 7)http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202003/46c9294a7dfe4cef80dc7f5912eb1989.shtml [2020-03-15] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China. National Recommendations for Diagnosis and Treatment of Severe/critical Novel Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) (Trial Edition 3) (in Chinese).

- 5.Xu Z., Shi L., Wang Y., et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:420–422. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30076-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu Q., Wang R.S., Qu G.Q., et al. Gross examination report of a COVID-19 death autopsy. Fa Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2020;36:21–23. doi: 10.12116/j.issn.1004-5619.2020.01.005. (in Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tian S., Xiong Y., Liu H., et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Digestion Association Chinese. Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Medical Association. The protocol for prevention, diagnosis and treatment of liver injury in coronavirus disease 2019. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2020;28:217–221. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501113-20200309-00095. (in Chinese) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wrapp D., Wang N., Corbett K.S., et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science. 2020;367:1260–1263. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y.F., Shi X.H., Li S.W., et al. Clinical manifestation of severe cases with COVID-19. J SUN Yat-sen Univ (Med Sci) 2020;41:184–190. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frontline Medical Panel of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun-Yat sen University Diagnosis and clinical management of severe 2019 novel coronavirus (2019n-CoV) infection: recommendations of the First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (V 1.0) J SUN Yat-sen Univ (Med Sci) 2020;41(2):161–173. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo W., Yu H., Gou J., et al. Clinical pathology of critical patient with novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) Preprints. 2020:2020020407. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202002.0407/v2 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen N., Zhou M., Dong X., et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu J., Liu Y., Xiang P., et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts critical illness patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in the early stage. J Transl Med. 2020;18:206. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02374-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C., et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen W., Lan Y., Yuan X., et al. Detectable 2019-nCoV viral RNA in blood is a strong indicator for the further clinical severity. Emerg Microb Infect. 2020;9:469–473. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1732837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu W., Wang J., Liu P., et al. A hospital outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Guangzhou, China. Chin Med J. 2003;116:811–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh K.M., Chiueh T.S., Siu L.K., et al. Experience of using convalescent plasma for severe acute respiratory syndrome among healthcare workers in a Taiwan hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2005;56:919–922. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soo Y.O., Cheng Y., Wong R., et al. Retrospective comparison of convalescent plasma with continuing high-dose methylprednisolone treatment in SARS patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2004;10:676–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2004.00956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen C., Wang Z., Zhao F., et al. Treatment of 5 critically Ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020;323:1582–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu F., Wang H.M., Wang T., Zhang Y.M., Zhu X. The efficacy of thymosin α1 as immunomodulatory treatment for sepsis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:488. doi: 10.1186/s12879-016-1823-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han H., Yang L., Liu R., et al. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58:1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemostasis. 2020;18:1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Covid-19 Treatment Guidelines Panel . National Institutes of Health; 2020. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu J., Feng L.C., Xian X.Y., et al. Novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19) CT distribution and sign features. Zhonghua Jiehe He Huxi Zazhi. 2020;43(4):321–326. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20200217-00106. (in Chinese) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alwarawrah Y., Kiernan K., MacIver N.J. Changes in nutritional status impact immune cell metabolism and function. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1055. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weimann A., Braga M., Carli F., et al. ESPEN guideline: clinical nutrition in surgery. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:623–650. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parenteral, enteral nutrition society of Chinese medical association . 2020. Expert Advice of Medical Nutrition Therapy on Covid-19 Patients.https://www.cma.org.cn/art/2020/1/30/art_15_32196.html (2020-01-30) [2020-02-05] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiang Y.T., Yang Y., Li W., et al. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:228–229. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Besedovsky L., Lange T., Haack M. The sleep-immune crosstalk in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:1325–1380. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li T., Yang W.R., Zheng X.B., et al. Psychological support for medical rescue teams in emergencies. J SUN Yat-sen Univ (Med Sci) 2020;41:174–179. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chinese Association of Rehabilitation Medicine Expert consensus on rehabilitation practices during outbreaks of the novel coronavirus pneumonia and other infectious respiratory diseases. Chin J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;42:97–101. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]