Abstract

This cross-sectional study examines the clinical and societal implications of the exansion of private equity in women’s health care.

An influx of private equity involvement in women’s health care has garnered attention and scrutiny.1 Over the past decade, private equity firms have increasingly invested in or acquired hospitals, physician practices, laboratories, and biomedical device companies. Private equity firms use capital from corporations or wealthy individuals to invest in and acquire organizations and generally sell their holdings within 3 to 7 years.2 Proponents argue that they produce economic value by increasing operational efficiency while maintaining or improving the quality of care. Critics fear that the need to quickly achieve high returns on investments may conflict with the quality and safety of care or exacerbate health inequities.3 Recent evidence shows growing acquisitions of physician groups across specialties between 2013 and 2016,4 which is aligned with larger trends in the corporatization of medicine.5 Despite the growth and geographic breadth of private equity involvement in health care, to our knowledge, relatively little empirical research exists, especially in women’s health.

We document formerly non–private equity women’s health care companies, including physician networks, practices, and fertility clinics, that gained a private equity affiliation between 2010 and 2019. This evidence aims to inform discussions about the clinical and societal implications of private equity in women’s health.

Methods

Using market reports and multiple methods of verification, we identified organizations (ie, target companies) specializing in women’s health that transitioned from non–private equity to private equity–affiliated between 2010 and 2019. Affiliations included direct acquisitions, recapitalizations, and undisclosed financial partnerships, with targets providing clinical obstetrics/gynecology (OB/GYN) or fertility services. We describe the method of identifying affiliations and inclusion criteria in eTable in the Supplement. This study was exempt from institutional board review because it did not involve human participants nor was any of the publicly available data used directly or indirectly based on human participant information.

We assessed whether OB/GYN offices are located in urban or rural areas by the zip code rural-urban commuting areas geographic taxonomy, version 3.10 (US Department of Agriculture). This mapping uses the 2010 Census work commuting data to classify zip codes from 1 (metropolitan) to 10 (rural) using the size and direction of primary commuting flows. We assessed average median household income using the zip codes for these offices.

Results

We found 24 target companies that gained private equity affiliation between 2010 and 2019 (Table). Acquisitions accelerated over the period studied, with 17 occurring between 2017 and 2019. In total, we found 605 offices and 2019 clinicians (ie, physicians, nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, and physician assistants) at the time of affiliation. As of 2020, we identified 1340 offices and 3989 clinicians.

Table. Women’s Health Organizations With Private Equity Affiliation From 2010 to 2019.

| Equity investora | Buyera | Target companya (description) | Year of completion | Offices at the time of affiliation | Clinicians at time of affiliationb | Current officesc | Current cliniciansb,c | Current location(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ares Private Equity Group | Ares Private Equity Group | Unified Physician Management (OB/GYN) | 2013 | NAd | 375e | 540 | 1700e | 12 Statesf |

| Audax | Audax | Women’s Health Care Group of PA (OB/GYN) | 2017 | 45 | 120e | NAg | NAg | Pennsylvania |

| Audax | Audax | Regional Women’s Health Group (OB/GYN) | 2017 | 65 | 165 | NAg | NAg | New Jersey |

| Audax | Axia Women’s Health | OB/GYN of Indiana (OB/GYN) | 2019 | 9 | 45b | 120e,g | 300g | Indiana |

| Deerfield Management Company | Deerfield Management Company | Advantia Health (OB/GYN) | 2016 | 10 | 12 | 48 | 200e | Washington DC, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, and Virginia |

| Lee Equity Partners | Prelude Fertility | Advanced Fertility Center of Chicago (fertility) | 2018 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | Illinois |

| Lindsay Goldberg | Lindsay Goldberg | Women’s Care Florida (OB/GYN) | 2017 | 71 | 230 | 100e | 360 | Florida |

| Lindsay Goldberg | Women’s Care Enterprises | London Women’s Care (OB/GYN) | 2019 | 1 | 29 | 1 | 28 | Kentucky |

| Lindsay Goldberg | Women’s Care Enterprises | North Florida Ob-Gyn (OB/GYN) | 2019 | 38 | 70e | 37 | 70e | Florida |

| Lindsay Goldberg | Women’s Care Enterprises | Palm Beach Obstetrics & Gynecology (OB/GYN) | 2019 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 9 | Florida |

| Regal Healthcare Capital Partners | Regal Healthcare Capital Partners | Extend Fertility (fertility) | 2019 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 | New York |

| Sagard Capital Partners | Sagard Capital Partners | IntegraMed America (fertility) | 2012 | 130 | NAd | 153 | 180 | 32 Statesh |

| Summit Partners | DuPage Medical Group | La Grange Women’s Clinic (OB/GYN) | 2016 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 4 | Illinois |

| Summit Partners | DuPage Medical Group | Southwest Women’s Healthcare Associates (OB/GYN) | 2016 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | Illinois |

| Summit Partners | DuPage Medical Group | Glenwood Medical Corp. (OB/GYN) | 2017 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | Illinois |

| Summit Partners | Summit Partners | Ob Hospitalist Group (OB/GYN) | 2010 | 120e,i | 600 | 180e,i | 700e | 32 Statesj |

| Sverica Capital Management | Women’s Health USA | Arizona OBGYN Affiliates (OB/GYN) | 2018 | 10 | 52 | 11 | 50 | Arizona |

| Sverica Capital Management | Women’s Health USA | Central Texas OB/GYN Associates (OB/GYN) | 2018 | NAd | NAd | 9 | 56 | Texas |

| Sverica Capital Management LLC | Women’s Health USA | Institute for Women’s Health (OB/GYN) | 2019 | 8 | 30 | 8 | 29 | Texas |

| Sverica Capital Management | Women’s Health USA | Women’s Health Connecticut (OB/GYN) | 2019 | 80 | 250e | 91 | 240 | Connecticut |

| TA Associates | TA Associates | CCRM (fertility) | 2015 | NAd | NAd | 23 | 34 | 9 Statesk |

| Webster Equity Partners | Webster Equity Partners | Santa Monica Fertility (fertility) | 2019 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | California and Florida |

| WindRose Health Investors | Ovation Fertility | Institute for Reproductive Health (fertility) | 2018 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 7 | Ohio and Kentucky |

| WindRose Health Investors | Ovation Fertility | Midwest Fertility Specialists (fertility) | 2018 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 4 | Indiana |

| Totals | 605 | 2019 | 1340 | 3989 | 38 States |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; OB/GYN, obstetrics/gynecology.

Equity investor refers to the private equity firm involved with the affiliation. Buyer refers to the company/subsidiary within the equity investor portfolio that is directly making the affiliation. When no buyer exists, the name of the equity investor is used. Target companies are the organizations specializing in women’s health that transitioned from non–private equity to private equity–affiliated between 2010 and 2019.

Clinicians include physicians, nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, and physician assistants.

We identified current offices and clinicians as of March 1, 2020.

Information could not be found in publicly available sources.

Numbers of offices or clinicians listed as over or nearly a certain value on publicly available sources have been rounded to that value.

Arizona, Washington D.C., Florida, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, North Carolina, New Jersey, New York, Texas, Virginia, and Washington.

Organization was fully incorporated into Axia Women’s Health; number indicates total count of consolidated offices/clinicians.

Publicly identifiable locations include Alabama, California, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Maryland, Missouri, Mississippi, North Carolina, Nevada, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, Virginia, and Washington.

Shows number of hospitals where affiliated clinicians practice.

Alaska, Alabama, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Maryland, Michigan, Missouri, Mississippi, North Carolina, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, Washington, and Wisconsin.

California, Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Texas, and Virginia.

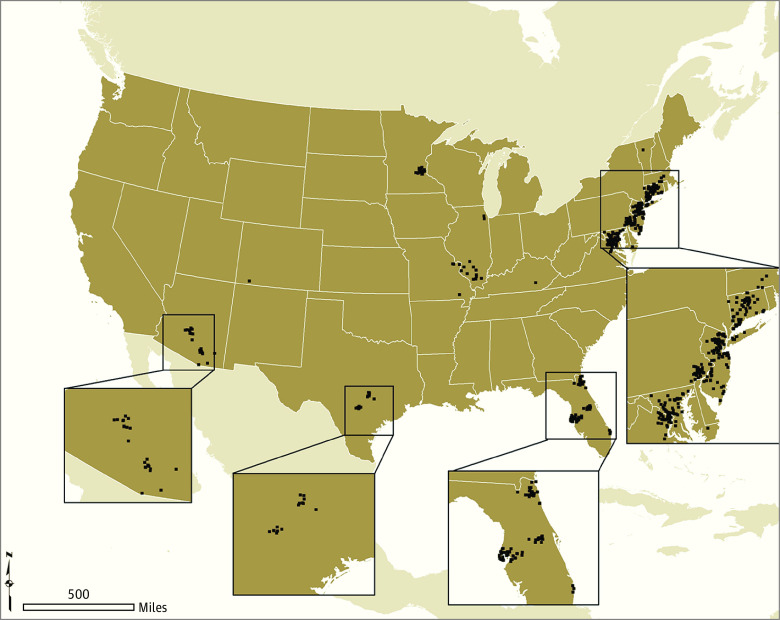

We found 17 target companies that were OB/GYN practices or networks and 7 target companies that provided fertility services. We located and mapped 533 (39.8%) of the 1340 offices of the 17 OB/GYN target companies in 2020. We excluded 180 hospitals contracted with the Ob Hospitalist Group (13.4%) and 439 offices (32.8%) without identifiable locations (Figure). Of the 533 offices, 240 (45.0%) were located in the Northeast, 229 (43.0%) in the South, 29 (5.5%) in the West, and 34 (6.4%) in the Midwest. Using the zip codes of these offices, we found that the average median (SE) household income was $76 107 ($1470) and the rural-urban commuting area score was 1.19 (0.04), which corresponds to a highly metropolitan area. Overall, 520 (97.6%) of these offices accepted Medicare and 453 (85.0%) accepted at least 1 form of Medicaid. Private insurance was accepted at all of these offices.

Figure. Private Equity–Affiliated Obstetrics/Gynecology (OB/GYN) Offices in 2020.

We mapped 533 OB/GYN offices in 2020, excluding the 180 hospitals contracted with Ob Hospitalist Group and 439 offices without identifiable locations. No mapped offices were located in Alaska or Hawaii.

Discussion

There has been a substantial increase in private equity affiliations in women’s health care since 2017. Private equity–affiliated OB/GYN offices are located in urban locations, with an average 2017 median household income 24% higher than the 2017 national average of $61 372.6 They generally accept Medicare, Medicaid, and private insurance. Several private equity firms have affiliations with multiple target companies, suggesting that these firms may have growing influence in women’s health.

Our analysis does not represent the totality of private equity investment in the women’s health sector. Target companies affiliated with private equity before 2010 whose affiliation was not publicly reported or who did not primarily provide OB/GYN or fertility services were excluded.

How the incentives of private equity firms interact with the clinical mission of women’s health is a critical area of inquiry. Future debate about private equity in women’s health will likely be shaped by the associations between economic incentives and quality of care, elective or cosmetic procedures, and access to reproductive health services, especially among low-income, LGBTQIA, and other disadvantaged populations.

eTable. Expanded Methodology

References:

- 1.Perlberg H. How private equity is ruining American health care. Accessed June 15, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2020-05-20/private-equity-is-ruining-health-care-covid-is-making-it-worse

- 2.Gondi S, Song Z. Potential implications of private equity investments in health care delivery. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1047-1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eren Vural I. Financialisation in health care: an analysis of private equity fund investments in Turkey. Soc Sci Med. 2017;187:276-286. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu JM, Hua LM, Polsky D. Private equity acquisitions of physician medical groups across specialties, 2013-2016. JAMA. 2020;323(7):663-665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casalino LP. The Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act and the corporate transformation of American medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(5):865-869. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontenot K, Semega J, Kollar M Income and poverty in the United States. Accessed April 12, 2020. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2018/demo/p60-263.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Expanded Methodology