Key Points

Question

Is the acquisition of a hospital by a private equity firm associated with changes in hospital income, use, and quality?

Findings

In this analysis of 204 private equity–acquired hospitals and 532 similar hospitals that were not acquired by private equity, net income, charges, charge to cost ratios, and the case mix index differentially increased for private equity–acquired hospitals after acquisition relative to controls. Some quality measures improved among a subset of private equity–acquired hospitals relative to controls; Medicare’s share of discharges decreased for private equity–acquired hospitals after acquisition relative to controls.

Meaning

Private equity acquisitions were associated with changes in a range of hospital-level economic measures and with improvements in a subset of quality measures.

Abstract

Importance

Rigorous evidence describing the relationship between private equity acquisition and changes in hospital spending and quality is currently lacking.

Objective

To examine changes in hospital income, use, and quality measures that may be associated with private equity acquisition.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study identified 204 hospitals acquired by private equity firms from 2005 to 2017 and 532 matched hospitals not acquired by private equity. Using a difference-in-differences design, this study evaluated changes in net income, charges, charge to cost ratios, case mix index (a measure of reported illness burden), share of discharges for patients with Medicare or Medicaid coverage, discharges per year, and aggregate hospital quality measures associated with private equity acquisition through 3 years after acquisition, adjusted for case mix, hospital beds, calendar year, and adjustment for multiple hypothesis testing. In subgroup analyses, changes in outcomes for private equity–owned Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) hospitals and non-HCA hospitals relative to matched controls were assessed.

Primary Outcomes and Measures

Eight hospital income and use measures and 3 aggregate hospital quality measures were examined.

Results

Relative to 532 control hospitals, the 204 private equity–acquired hospitals showed a mean increase of $2 302 391 (95% CI, $956 660-$3 648 123; P = .009) in annual net income, an increase of $407 (95% CI, $296-$518; P < .001) in total charge per inpatient day, an increase of 0.61 (95% CI, 0.48-0.73; P < .001) in emergency department charge to cost ratio, an increase of 0.31 (95% CI, 0.26-0.37; P < .001) in total charge to cost ratio, an increase of 0.02 (95% CI, 0.01-0.02; P = .007) in case mix index, and a decrease of 0.96% (95% CI, 0.46%-1.45%; P = .002) in share of Medicare discharges. Medicaid’s share of discharges (−0.16%; 95% CI, −0.86% to 0.53%; P > .99) and total hospital discharges (98; 95% CI, −54 to 250; P > .99) did not change differentially in a statistically significant manner. The aggregate quality score for acute myocardial infarction increased by 3.3% (95% CI, 1.6%-5.0%; P = .002), and the aggregate score for pneumonia increased by 2.9% (95% CI, 1.8%-3.9%; P < .001) in private equity–acquired hospitals relative to controls. The aggregate score for heart failure (1.3%; 95% CI, −0.2% to 2.7%; P = .92) did not differentially change in a statistically significant manner. In subgroup analyses, HCA hospitals showed similar findings to the entire sample. Among non-HCA hospitals, the only statistically significant relative changes were the increase in the emergency department charge to cost ratio (0.30; 95% CI, 0.12-0.48; P = .02) and the decrease in Medicare’s share (−1.15%; 95% CI, −1.88% to −0.43%; P = .02). Non-HCA hospitals showed a decrease in the aggregate heart failure score (−3.3%; 95% CI, −5.3% to −1.3%; P = .01) and no statistically significant changes in the aggregate score for acute myocardial infarction (2.4%; 95% CI, −0.7% to 5.4%; P > .99) or pneumonia (0.2%; 95% CI, −1.4% to 1.7%; P > .99).

Conclusions and Relevance

Hospitals acquired by private equity were associated with larger increases in net income, charges, charge to cost ratios, and case mix index as well as with improvement in some quality measures after acquisition relative to nonacquired controls. Heterogeneity in some findings was observed between HCA and non-HCA hospitals.

This difference-in-differences analysis assesses whether an association exists between hospitals being acquired by private equity firms and hospital income, use, and quality in the United States.

Introduction

Private equity investment in health care has markedly increased in recent years. The total disclosed value of private equity deals in health care reached $78.9 billion in 2019, up from $23.1 billion in 2015.1,2 Private equity firms use capital from institutional investors and individuals to acquire assets, such as hospitals and physician practices. After acquisition, private equity fund managers use the control offered by their newly purchased ownership stake to increase the value of the asset before selling it generally for a profit, typically in 3 to 7 years. Common strategies to enhance the value of acquired businesses include cutting costs and increasing efficiency.

In North America, the health care provider sector, which includes for purposes of this study hospitals, physician practices, and laboratory services, comprised more than half of all private equity health care deals in 2019.1 Several factors may explain why health care is attractive to private equity firms.3 First, demand for health care has historically been relatively stable through economic fluctuations. Second, many health care delivery markets are fragmented, presenting opportunities for private equity firms to acquire numerous hospitals or physician practices to consolidate market power and to extract higher payments from payers. Third, private equity fund managers may seek to profit from increasing the efficiency of care delivery in a health care system in which up to a quarter of spending may be waste.4 To date, private equity acquisitions of physician practices have been noted in specialties such as dermatology, ophthalmology, radiology, and primary care.5,6,7,8,9,10 As practices and hospitals struggle with lost revenue during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, they may become more susceptible to private equity acquisition.11

Although prior research has evaluated changes in quality following hospital mergers,12 little empirical evidence exists on changes in hospital income, use, or quality after a hospital is acquired by a private equity firm, despite the well-documented increase in such acquisitions.13,14,15,16,17

We identified US hospitals acquired by private equity firms between 2005 and 2017 and evaluated changes in hospital income, use, and quality associated with private equity acquisition for 3 years after the acquisition. Because a single acquisition (Hospital Corporation of America [HCA] acquired by Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, Bain Capital, and Merrill Lynch Global) constitutes a significant portion of all hospitals acquired in this time period, we separately analyzed hospitals in the HCA acquisition and those involved in other private equity (non-HCA) acquisitions in subgroup analyses.

Methods

Data Acquisition

We created a novel data set of acute care hospitals in the US that were acquired by private equity firms. Private equity firms often do not directly purchase a hospital. Instead, the purchaser is frequently a subsidiary company that the private equity firm owns. In addition, the hospital is often part of a large health system or delivery organization being acquired by private equity. Given the intricacies of the acquisition structure, data on hospitals acquired by private equity firms are difficult to assemble. To overcome these challenges, we used S&P Global Market Intelligence software to obtain a list of all transactions whereby a private equity firm gained control of a hospital by directly purchasing it, having a portfolio company purchase the hospital, or by owning a majority of the stock in a health system. We supplemented these data with information from quarterly Merger and Acquisition reports by Irving Levin Associates. We then used documents from the US Securities and Exchange Commission, official press releases, and hospital websites to verify that the hospital was acquired. To verify that the firm (or parent company) acquiring the hospital was considered private equity, we consulted the PitchBook database, which provides information on company profiles.18 Drawing from the above resources, we assembled an original data set of 217 US acute care hospitals between 2005 and 2017 that transitioned from not being owned by private equity to being owned by private equity (eTable 1 in the Supplement), of which 135 hospitals (62.2%) were part of the 2006 acquisition of HCA. The Institutional Review Board of Harvard Medical School approved this work. In this analysis, all data were in the public domain, and no data were at the human subject level.

We obtained Medicare Cost Report data from 2002 to 2018. These data come from the Healthcare Provider Cost Reporting Information System and reflect yearly annual cost reports that Medicare-certified institutions submit to Medicare. Medicare Cost Reports contain information on facility characteristics, hospital use, costs, reimbursements, patient discharges, and other financial statement data. Using Medicare Cost Reports, we verified that all hospitals included in the sample were acute care hospitals and that their names and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provider numbers matched the records of private equity transactions. We extracted data on hospital income, use, and facility characteristics.

Finally, we obtained hospital case mix index data on discharges using publicly available Acute Inpatient CMS files. The case mix index value is the sum of diagnosis-related group weights for all Medicare discharges divided by the number of discharges.

Hospital Income and Use

We collected yearly data on the following hospital income and use measures: net income (total revenue minus total expenses), total charge per inpatient day, emergency department charge to cost ratio, total charge to cost ratio (a reflection of hospital markups that has been used elsewhere19), case mix index (a measure of disease burden), the share of discharges accounted for by patients with Medicare, the share of discharges accounted for by patients with Medicaid, and total hospital discharges (defined in eTable 2 in the Supplement).

To address rare outlier values, we followed established methods and winsorized all hospital income and use measures to the 95th and 5th percentiles; in other words, we set all values above and below those thresholds to their respective threshold value. This technique reduces the influence of severe outliers (which may reflect errors in data entry) and is commonly done in research using Medicare Cost Reports.20,21

We also gathered several facility-level attributes. Ownership was defined as nonprofit, government, or for-profit. Hospital referral region (HRR) data were obtained from the Dartmouth Atlas. The HRRs represent regional health care markets between which variation in medical care has been investigated.

Process Quality Measures

We extracted quality of care process measures from Hospital Compare, a CMS website that provides information on hospital performance using quality measures. Because Hospital Compare has changed its process of care measures over time, we found only 8 individual measures that remained relatively consistent in definition during the period of the study. These 8 process measures pertained to 3 conditions: heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia. For the analyses, we used these 3 aggregate measures, which are the weighted averages of individual measures in each condition.

Statistical Analysis

We used a difference-in-differences design within an event study framework to assess changes in outcomes associated with private equity acquisition of hospitals. We used an analytic design similar to that in Joynt et al,22 who evaluated hospital conversions from nonprofit to for-profit status. Private equity–acquired hospitals were matched to control hospitals at event time 0 (the year of acquisition). We used nearest neighbor matching on total beds and exact matching on year, ownership, US geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and teaching hospital status. We allowed for up to 8 controls per private equity–acquired hospital. In total, we found data and matches for 204 of the 217 hospitals. There were 532 matched controls.

In the event study, we lined up all hospitals and their outcome data at event time 0, the year of acquisition, and looked back 3 years prior to private equity acquisition and 3 years after private equity acquisition. Because full cost report data are available only to 2018, hospitals acquired in 2016 and 2017 contributed 2 years and 1 year of data following acquisition, respectively. The year of acquisition was excluded as a washout period from all analyses. We followed the same design for process quality measures but could only include 2 years prior to acquisition and 3 years after acquisition and only among hospitals acquired from 2005 to 2013. This truncated period was necessary because most quality measures were only consistent from 2004 to 2016. We reported missing observations in eTable 3 in the Supplement.

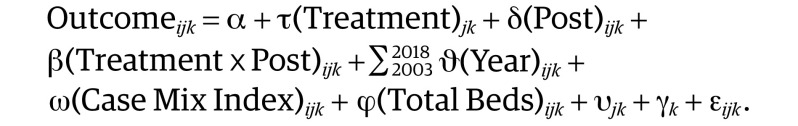

We used a linear mixed-effects model to compare changes in outcomes among private equity–acquired hospitals relative to control hospitals from before to after the acquisition. We included year fixed effects to adjust for secular trends in the outcomes. We controlled for case mix index. To capture the multilevel study design, we included a random intercept term for the matched group and the provider group, which is the unique Medicare identification number for the hospital. We defined the “Treatment” indicator as a hospital that transitioned from not owned by private equity to being acquired by private equity. We defined a “Post” indicator that represents event years after private equity acquisition:

|

In this model, “Outcome” denotes an outcome of interest, such as total hospital discharges or quality for event year i in hospital j in matched group k. The adjusted difference-in-differences estimate is denoted by the coefficient β on the interaction term “Treatment × Post.” “Case Mix Index” and “Total Beds” were mean values centered prior to entry into the model; υ is the random intercept for each provider group, and γ is the random intercept for each matched group. Evaluating 11 outcomes in total, we used the Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple comparisons testing and reported Bonferroni-corrected P values.23 A 2-sided value of P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

We conducted several sensitivity analyses. First, because some of the hospitals had fiscal years that did not correspond to the calendar year, we extended our washout period, excluding time 0 as well as time 1 and time −1 to prevent the precise time of acquisition from being possibly captured in the before or after period. Second, we included HRR fixed effects interacted with year to better capture mean within-region changes over time. In a third sensitivity analysis, we removed case mix index and total beds from our model.

Although there is debate over whether to match on preintervention outcomes, matching on preintervention outcome levels may reduce bias when treatment is based on preintervention outcomes.24,25 Thus, in a fourth sensitivity analysis, we performed exact matching on year, ownership, region, and teaching status and performed nearest neighbor matching on net income, total inpatient charges per day, charge to cost ratio, case mix index, total proportion of discharges with public health insurance (Medicare and Medicaid discharges), and hospital discharges.

We tested for differences in preacquisition trends between the private equity–acquired hospitals and control hospitals by performing joint F tests of the hypothesis that preintervention interactions between the treatment and event time indicators are zero for time −2 and −1 (with time −3 as the reference) for hospital income and use outcomes. For quality measures, we tested the interaction between private equity acquisition and time −1 (with time −2 as the reference). In subgroup analyses, we assessed changes in outcomes associated with the acquisition of HCA hospitals and non-HCA hospitals separately. All statistical analyses were conducted using R software, version 3.6.1 (The R Foundation).

Results

The characteristics of 204 private equity–acquired hospitals during the year of the acquisition (time 0) and 532 control hospitals are shown in Table 1. Most hospitals in the sample were nonteaching (149 private equity–acquired hospitals [73.0%]; 393 control hospitals [73.9%]), for-profit (172 private equity–acquired hospitals [84.3%]; 448 control hospitals [84.2%]), and located in the Southern US Census region (125 private equity–acquired hospitals [61.3%]; 325 control hospitals [61.1%]).

Table 1. Characteristics of 204 Private Equity–Acquired Hospitals and 532 Control Hospitalsa.

| Characteristic | Hospitals, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Private equity acquisition | Control | |

| Hospital ownership | ||

| Nonprofit | 29 (14.2) | 76 (14.3) |

| Government | 3 (1.5) | 8 (1.5) |

| For profit | 172 (84.3) | 448 (84.2) |

| Geographic region | ||

| South | 125 (61.3) | 325 (61.1) |

| West | 37 (18.1) | 97 (18.2) |

| Northeast | 21 (10.3) | 55 (10.3) |

| Midwest | 21 (10.3) | 55 (10.3) |

| Teaching hospital | 55 (27.0) | 139 (26.1) |

| Hospital size by total No. of beds, mean No. | 212 | 200 |

| Small (<150 beds), % | 30.9 | 40.8 |

| Medium (150-350 beds), % | 56.4 | 45.1 |

| Large (>350 beds), % | 12.8 | 14.2 |

Private equity–acquired hospitals were matched to controls at event time 0 (time of acquisition). R Package MatchIt was used to generate at most 8 controls per private equity–acquired hospital. We used nearest neighbor matching on total beds and exact matching on year, ownership, geographic region, and teaching hospital status. Values are calculated using weights derived from matching. Within matched groups, we weighted each target as 1 and assigned controls weights that summed to 1.

Hospital Income and Use

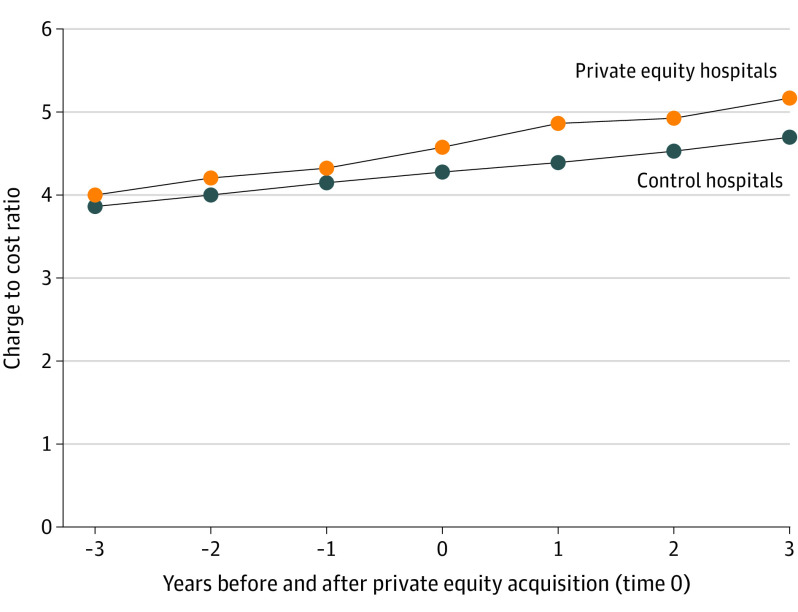

Changes in hospital income and use are shown in Table 2, with mean values before and after private equity acquisition. Means were calculated using an unadjusted model, which included a random intercept for the matched group and for the provider group, with no covariates. The charge to cost ratio, a representative outcome, is plotted in the Figure, which shows an increase for private equity–owned hospitals after acquisition relative to controls.

Table 2. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures After Private Equity Acquisition.

| Measure | Hospitals | Differential change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquired hospitals (n = 204) | Control hospitals (n = 532) | Unadjusted, No.a | Adjusted, No. (%) [95% CI]b | P value | Corrected P valuec | |||||

| Before private equity | After private equity | Change | Before private equity | After private equity | Change | |||||

| Net income per y, $ | 8 527 119 | 12 861 680 | 4 334 561 | 7 655 125 | 10 092 820 | 2 437 695 | 1 896 866 | 2 302 391 (27.0) [956 660 to 3 648 123] | .001 | .009 |

| Total charge per inpatient day, $ | 5789 | 7766 | 1978 | 5583 | 6928 | 1345 | 633 | 407 (7.0) [296 to 518] | <.001 | <.001 |

| Emergency charge to cost ratio | 3.81 | 5.52 | 1.71 | 4.00 | 5.03 | 1.02 | 0.69 | 0.61 (16.0) [0.48 to 0.73] | <.001 | <.001 |

| Total charge to cost ratio | 4.17 | 5.02 | 0.85 | 3.90 | 4.38 | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.31 (7.4) [0.26 to 0.37] | <.001 | <.001 |

| Case mix index | 1.42 | 1.47 | 0.05 | 1.36 | 1.41 | 0.05 | 0.00 | 0.02 (1.4) [0.01 to 0.02] | .001 | .007 |

| Medicare’s share of discharges, % | 40.3 | 36.8 | −3.5 | 39.1 | 37.1 | −2.0 | −1.56 | −0.96 (−2.4) [−1.45 to −0.46] | <.001 | .002 |

| Medicaid’s share of discharges, % | 13.2 | 12.2 | −1.0 | 15.2 | 14.3 | −0.9 | −0.07 | −0.16 (−1.2) [−0.86 to 0.53] | .64 | >.99 |

| Total discharges per y, No. | 8948 | 9181 | 233 | 8504 | 8353 | −151 | 384 | 98 (1.1) [−54 to 250] | .21 | >.99 |

Private equity–acquired hospitals were matched to controls at event time 0 (time of acquisition). R Package MatchIt was used to generate at most 8 controls per acquired hospital. We used nearest neighbor matching on total beds and exact matching on year, ownership, region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and teaching hospital status. The unadjusted model refers to the mixed-effects model, which included a random intercept for the matched group and for the provider group, with no covariates. Values indicate means before and after private equity acquisition of acquired and control hospitals and were calculated using the unadjusted model.

The adjusted model included a random intercept term for the matched group and for the provider group and adjusted for calendar year, case mix index, and total hospital beds. Case mix index was not included as a covariate when evaluated as an outcome. Percentage differential change was calculated by dividing the adjusted differential change by the preacquisition mean among private equity–acquired hospitals.

Bonferroni correction used for multiple comparisons testing.

Figure. Total Charge to Cost Ratios Before and After Private Equity Acquisition.

Weighted mean values at each event time. The mean values are calculated using weights derived from matching. Within matched groups, we weighted each target as 1 and assigned controls weights that summed to 1.

In adjusted analyses, private equity–acquired hospitals demonstrated a mean increase of $2 302 391 (95% CI, $956 660-$3 648 123; P = .009) in annual net income, an increase of $407 (95% CI, $296-$518; P < .001) in total charge per inpatient day, an increase of 0.61 (95% CI, 0.48-0.73; P < .001) in emergency department charge to cost ratio, an increase of 0.31 (95% CI, 0.26-0.37; P < .001) in total charge to cost ratio, and an increase of 0.02 (95% CI, 0.01-0.02; P = .007) in case mix index relative to control. Medicare’s share of discharges decreased by 0.96% (95% CI, 0.46%-1.45%, P = .002) in private equity–acquired hospitals relative to controls. Medicaid’s share of discharges (−0.16%; 95% CI, −0.86% to 0.53%, P > .99) and total hospital discharges (98; 95% CI, −54 to 250; P > .99) did not change differentially in a statistically significant manner.

Process Quality Measures

Unadjusted levels and changes in quality measures are shown in Table 3. In adjusted analysis, the aggregate score for acute myocardial infarction increased by 3.3 percentage points (95% CI, 1.6%-5.0%; P = .002) and for pneumonia by 2.9 percentage points (95% CI, 1.8%-3.9%; P < .001) in private equity–acquired hospitals relative to controls. The aggregate score for heart failure (1.3 percentage points; 95% CI, −0.2% to 2.7%; P = .92) did not differentially change in a statistically significant manner.

Table 3. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures After Private Equity Acquisitiona.

| Measure | Hospitals | Differential change | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acquired hospitals (n = 179) | Control hospitals (n = 404) | Unadjustedb | Adjusted, No. (%) [95% CI]c | P value | Corrected P valued | |||||

| Before private equity | After private equity | Change | Before private equity | After private equity | Change | |||||

| Heart failuree | 75.2 | 93.6 | 18.4 | 76.7 | 89.4 | 12.7 | 5.7 | 1.3 (1.7) [−0.2 to 2.7] | .08 | .92 |

| Acute myocardial infarctionf | 89.3 | 97.5 | 8.2 | 89.8 | 93.6 | 3.8 | 4.4 | 3.3 (3.7) [1.6 to 5.0] | <.001 | .002 |

| Pneumoniag | 73.7 | 95.4 | 21.7 | 77.2 | 91.4 | 14.2 | 7.5 | 2.9 (3.9) [1.8 to 3.9] | <.001 | <.001 |

The aggregate quality measures are the weighted averages of individual measures within each condition category. Values correspond to the proportion (%) of eligible patients for a measure who met quality performance for the measure.

Private equity–acquired hospitals were matched to controls at time 0 (time of acquisition). R Package MatchIt was used to generate at most 8 controls per acquired hospital. We used nearest neighbor matching on total beds and exact matching on year, ownership, region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and teaching hospital status. The unadjusted model refers to the mixed-effects model, which included a random intercept for the matched group and for the provider group, with no covariates. Values indicate means before and after private equity for acquired and control hospitals and were calculated using the unadjusted model.

The adjusted model included a random intercept term for the matched group and for the provider group and adjusted for calendar year, case mix index, and total hospital beds. Percentage differential change was calculated by dividing the adjusted differential change by the preacquisition mean among acquired hospitals.

Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons testing.

Heart failure included Hf1 (2004-2014), Hf2 (2004-2015), and Hf3 (2004-2014); Hf1 represents patients with heart failure given discharge instructions; Hf2, patients with heart failure given an assessment of left ventricular function; and Hf3, patients with heart failure given an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker for left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

Acute myocardial infarction included Ami2 (2004-2014); Ami2 represents patients with an acute myocardial infarction given aspirin at discharge.

Pneumonia included Pn2 (2004-2011), Pn3 (2004-2012), Pn5 (2004-2011), and Pn6 (2004-2015); Pn2 represents patients with pneumonia assessed and given pneumococcal vaccination; Pn3, patients with pneumonia who received a blood culture performed prior to first antibiotic received in hospital; Pn5, patients with pneumonia given initial antibiotic(s) within 4 hours after arrival; and Pn6, patients with pneumonia given the most appropriate initial antibiotic(s).

Sensitivity Analyses

Our main results were relatively similar when we widened our washout period around the time of private equity acquisition (eTables 4 and 5 in the Supplement). The findings were relatively similar after removing case mix index and total beds as covariates (eTables 8 and 9 in the Supplement) and matching on preintervention outcomes (eTables 10 and 11 in the Supplement). When we included HRR and year interactions in the model (eTables 6 and 7 in the Supplement) as well as when we performed a fixed-effects model (eTables 12 and 13 in the Supplement), most of our estimates remained relatively similar, although with the Bonferroni adjustment, some of the corrected P values were larger. A joint F test to assess differences in preacquisition trends for hospital income and use measures as well as process quality measures did not show a significant difference for any of the 11 measures (eTable 14 in the Supplement).

HCA and Non-HCA Analysis

Baseline characteristics of HCA hospitals compared with non-HCA hospitals are given in eTable 15 in the Supplement. Prior to acquisition, HCA hospitals were almost entirely for-profit and located in the South, whereas about half of non-HCA hospitals were nonprofit and geographically dispersed. The HCA hospitals had more discharges annually than non-HCA hospitals.

In the subgroup analysis of HCA hospitals and matched controls, changes in income, use, and quality measures associated with the acquisition were generally similar to the main results, with most estimates larger in magnitude (eTables 16 and 17 in the Supplement). In the analysis of non-HCA hospitals and matched controls, most hospital income and use outcomes did not change differentially after private equity acquisition, except emergency department charge to cost ratios, which increased, and Medicare’s share of discharges, which slightly decreased (eTable 18 in the Supplement). The mean aggregate measure for heart failure decreased by 3.3 percentage points (95% CI, 1.3%-5.3%; P = .01) more among private equity–acquired hospitals than control hospitals (eTable 19 in the Supplement). The other quality measures did not change in a statistically significant manner among non-HCA hospitals relative to controls.

Discussion

Private equity has a substantial and growing presence in the US health care system, especially in the hospital sector. Although private equity firms may seek to create efficiencies in the delivery of care, their financial incentives, especially the pressure to sell acquired assets for a profit on a short time horizon, might conflict with parts of the mission and priorities of health care clinicians.3 Anecdotal reports suggest that private equity–owned health care organizations may be more likely to operate in ways that maximize margin in the near term.5,26,27 Payers may be appropriately concerned about the potential for increased health care spending that may be lower value. Most worrisome are suggestions of risk to patient safety and health equity.28 Consequently, understanding the potential implications of private equity acquisitions of hospitals is important for patients, payers, and policy makers.

In this initial analysis of 204 hospitals acquired by private equity from 2005 to 2017, we found that relative to 532 control hospitals, private equity acquisition was associated with increases in annual net income, hospital charges, charge to cost ratios, and case mix index among hospitals. The proportion of patients discharged from hospitals acquired by private equity who were covered by Medicare decreased relative to control hospitals, whereas the proportion covered by Medicaid was unchanged, suggesting an increase in the share of discharges for patients who were privately insured or uninsured relative to controls. Patients who are privately insured typically garner higher reimbursements for hospitals than patients with Medicare or Medicaid.

Although the total hospital charge is the amount the hospital bills for care, it is typically not what insurers or patients pay the hospital (negotiated payment rates are less than the charge). Nevertheless, the charge represents the “asking price,” and is often the billed amount for patients paying out of pocket, including uninsured or out-of-network patients.29,30 Higher charges are also associated with greater payment among insured, in-network patients.31 The higher charge to cost ratio we observed may indicate that hospitals acquired by private equity firms began charging more for services, cutting operating costs, or both after the acquisition.

Increased charges following private equity acquisition provides insight into the strategic decisions made by fund managers or hospital leadership in response to new incentives hospitals face after an acquisition. Higher markups are associated with greater profitability.32 The increase in yearly case mix index suggests that hospitals saw reportedly sicker patients on average after acquisition. This could be due to selection effects if the composition of patients changed. However, it may also suggest that hospitals are engaging in more complete or aggressive coding. Upcoding can lead to higher diagnosis-related group payments for inpatient admissions and is another possible mechanism to increase net income.33

In our main analysis, we observed greater improvements in process quality measures among private equity–acquired hospitals relative to controls, which may reflect better care for patients. However, it could also be consistent with better adherence to compliance standards or efforts to maximize opportunities for quality bonuses under pay-for-performance contracts.

Subgroup analyses showed that our aggregate results were driven by the subsample of HCA hospitals. Nevertheless, among non-HCA hospitals, the emergency department charge to cost ratios also increased relative to control. However, non-HCA hospitals showed a decline in 1 quality measure relative to control and no relative improvements in the others. These findings could reflect differences between HCA and non-HCA hospitals. For instance, HCA hospitals differed from non-HCA hospitals in location, ownership, and total discharges. Furthermore, HCA has focused on market power, volume, and performance on quality measures.34,35,36,37 That HCA hospitals saw improvements in quality measures whereas non-HCA hospitals did not could reflect different priorities across different private equity owners. Owing to the oversized influence of HCA hospitals in our sample, the results for non-HCA hospitals—reduction in a quality measure and increase in emergency department charge to cost ratio—may be more representative of private equity acquisitions in general.

Limitations

We highlight several limitations. First, the difference-in-differences design is vulnerable to unobserved confounding. This study did not capture potential differences in patient populations before and after acquisition. It is possible that hospitals acquired by private equity firms selected for certain patient populations after acquisition. Changes in charges may thus reflect changes in patient populations. Although we partially controlled for changes in patient population by including the case mix index as a covariate, it is limited by its focus on the Medicare population and there may be additional unobservable characteristics that changed differentially for private equity–acquired hospitals relative to controls.

Second, the preacquisition and postacquisition trends were relatively short given the data available, rendering it more difficult for statistical tests to detect significant differences. This could lead preintervention trends between groups to appear more similar, although, as far as the data would allow, a consistent lack of significant differences in preacquisition trends was found.

Third, the number of quality measures available was small, making it difficult to assess changes in quality measures broadly. Moreover, no hospital-level health outcome measures were systematically available.

Conclusions

As private equity increasingly influences health care delivery in the US, this study offers an initial national assessment of changes in hospital-level economic and quality measures associated with private equity acquisition. Although further research is needed, our findings suggest that policy makers should consider monitoring or thoughtful oversight of changes in care delivery and billing practices in hospitals acquired by private equity firms to ensure proper stewardship of societal resources and the prioritization of patient interests.

eTable 1. Private Equity Firm Hospital Acquisitions

eTable 2. Medicare Cost Report Measures

eTable 3. Missing Data for Outcome Measures

eTable 4. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Excluding Washout Period Time -1 and Time 1)

eTable 5. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Excluding Washout Period Time -1 and Time 1)

eTable 6. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Including Hospital Referral Region and Year Interactions)

eTable 7. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Including Hospital Referral Region and Year Interactions)

eTable 8. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Removing Case Mix Index and Total Beds as Covariates)

eTable 9. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Removing Case Mix Index and Total Beds as Covariates)

eTable 10. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Matching on Pre-Intervention Outcomes)

eTable 11. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Matching on Pre-Intervention Outcomes)

eTable 12. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Fixed Effects Model)

eTable 13. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Fixed Effects Model)

eTable 14. Differences in Pre-Acquisition Trends

eTable 15. Characteristics of HCA-Acquired Hospitals and Non-HCA Acquired Hospitals

eTable 16. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (HCA Hospitals)

eTable 17. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (HCA Hospitals)

eTable 18. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Non-HCA Hospitals)

eTable 19. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Non-HCA Hospitals)

References

- 1.Bain & Co Global healthcare private equity and corporate M&A report 2020. Bain. Published 2020. Accessed April 13, 2020. https://www.bain.com/globalassets/noindex/2020/bain_report_global_healthcare_private_equity_and_corporate_ma_report_2020.pdf

- 2.Bain & Co Global healthcare private equity and corporate M&A report 2016. Published April 20,2016. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://www.bain.com/insights/global-healthcare-private-equity-and-corporate-ma-report-2016/

- 3.Gondi S, Song Z. Potential implications of private equity investments in health care delivery. JAMA. 2019;321(11):1047-1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA. 2019;322(15). doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.13978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Resneck JS., Jr Dermatology practice consolidation fueled by private equity investment: potential consequences for the specialty and patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(1):13-14. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konda S, Francis J, Motaparthi K, Grant-Kels JM; Group for Research of Corporatization and Private Equity in Dermatology . Future considerations for clinical dermatology in the setting of 21st century American policy reform: corporatization and the rise of private equity in dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(1):287-296. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.09.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleishon HB, Vijayasarathi A, Pyatt R, Schoppe K, Rosenthal SA, Silva E III. White paper: corporatization in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(10):1364-1374. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel SN, Groth S, Sternberg P Jr. The emergence of private equity in ophthalmology. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2019;137(6):601-602. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2019.0964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan S, Seiger K, Renehan P, Mostaghimi A. Trends in private equity acquisition of dermatology practices in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(9):1013-1021. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.1634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu JM, Hua LM, Polsky D. Private equity acquisitions of physician medical groups across specialties, 2013-2016. JAMA. 2020;323(7):663-665. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abelson R. Doctors without patients: “our waiting rooms are like ghost towns.” New York Times May 5, 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/05/health/coronavirus-primary-care-doctor.html

- 12.Beaulieu ND, Dafny LS, Landon BE, Dalton JB, Kuye I, McWilliams JM. Changes in quality of care after hospital mergers and acquisitions. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):51-59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1901383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LifePoint Health LifePoint Health and RCCH HealthCare Partners announce completion of merger. Published November, 2018. Accessed September 4, 2019. http://lifepointhealth.net/news/2018/11/16/lifepoint-health-and-rcch-healthcare-partners-announce-completion-of-merger

- 14.Community Health Systems. Press room and media releases: Community Health Systems completes divestiture of eight hospitals to Steward Health. Published May, 2017. Accessed September 2, 2019.https://www.chs.net/investor-relations/press-room-media-releases/

- 15.Humana. Humana, together with TPG Capital and Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe, announce completion of the acquisition of Kindred Healthcare, Inc. Published July 2, 2018. Accessed September 2, 2019. https://press.humana.com/press-release/current-releases/humana-together-tpg-capital-and-welsh-carson-anderson-stowe-announc-0

- 16.KKR KKR completes acquisition of Envision Healthcare Corporation. Published October 11, 2018. Accessed September 11, 2019. https://media.kkr.com/news-releases/news-release-details/kkr-completes-acquisition-envision-healthcare-corporation

- 17.Rosenbaum L. Losing Hahnemann—real-life lessons in “value-based” medicine. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1193-1195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1911307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitchbook. Profile previews—driven by the PitchBook platform. Published 2020. Accessed July 13, 2020. https://pitchbook.com/profiles/.

- 19.Bai G, Anderson GF. Extreme markup: the fifty US hospitals with the highest charge-to-cost ratios. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(6):922-928. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.RTI International. Using Medicare cost reports to calculate costs for post-acute care claims. Published January 2017. Accessed July 14, 2020. https://www.rti.org/rti-press-publication/medicare-cost-reports-PAC [PubMed]

- 21.Ly DP, Jha AK, Epstein AM. The association between hospital margins, quality of care, and closure or other change in operating status. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1291-1296. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1815-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Association between hospital conversions to for-profit status and clinical and economic outcomes. JAMA. 2014;312(16):1644-1652. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.13336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonferroni CE. Il calcolo delle assicurazioni su gruppi di teste. In: Studi in Onore del Professore Salvatore Ortu Carboni Rome, Italy; 1935:13-60. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daw JR, Hatfield LA. Matching in difference-in-differences: between a rock and a hard place. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(6):4111-4117. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.13017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan AM, Burgess JF Jr, Dimick JB. Why we should not be indifferent to specification choices for difference-in-differences. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(4):1211-1235. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casalino LP, Saiani R, Bhidya S, Khullar D, O’Donnell E. Private equity acquisition of physician practices. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(2):114-115. doi: 10.7326/M18-2363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Donnell EM, Lelli GJ, Bhidya S, Casalino LP. The growth of private equity investment in health care: perspectives from ophthalmology. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):1026-1031. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Institute for New Economic Thinking: Center for Economic and Policy Research. Private equity buyouts in healthcare: who wins, who loses? working paper No. 118. Published March 15, 2020. Accessed July 14, 2020. https://www.ineteconomics.org/uploads/papers/WP_118-Appelbaum-and-Batt-2-rb-Clean.pdf

- 29.Tompkins CP, Altman SH, Eilat E. The precarious pricing system for hospital services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2006;25(1):45-56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song Z, Johnson W, Kennedy K, Biniek JF, Wallace J. Out-of-network spending mostly declined in privately insured populations with a few notable exceptions from 2008 to 2016. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):1032-1041. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Batty M, Ippolito B. Mystery of the chargemaster: examining the role of hospital list prices in what patients actually pay. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):689-696. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bai G, Anderson GF. A more detailed understanding of factors associated with hospital profitability. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):889-897. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dafny LS. How do hospitals respond to price changes? Am Econ Rev. 2005;95(5):1525-1547. doi: 10.1257/000282805775014236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harvard Business School Faculty & Research. Capital allocation at HCA. Case 218-039. Published January 2018. Revised December 2018. Accessed July 14, 2020. https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=53790

- 35.Clark SL, Meyers JA, Frye DK, Perlin JA. Patient safety in obstetrics—the Hospital Corporation of America experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(4):283-287. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.12.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown PP, Houser F, Kugelmass AD, et al. . Cardiovascular centers of excellence program: a system approach for improving the care and outcomes of cardiovascular patients at HCA hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(11):647-659. doi: 10.1016/S1553-7250(07)33074-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCue MJ, Thompson JM. The impact of HCA’s 2006 leveraged buyout on hospital performance. J Healthc Manag. 2012;57(5):342-356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Private Equity Firm Hospital Acquisitions

eTable 2. Medicare Cost Report Measures

eTable 3. Missing Data for Outcome Measures

eTable 4. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Excluding Washout Period Time -1 and Time 1)

eTable 5. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Excluding Washout Period Time -1 and Time 1)

eTable 6. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Including Hospital Referral Region and Year Interactions)

eTable 7. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Including Hospital Referral Region and Year Interactions)

eTable 8. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Removing Case Mix Index and Total Beds as Covariates)

eTable 9. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Removing Case Mix Index and Total Beds as Covariates)

eTable 10. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Matching on Pre-Intervention Outcomes)

eTable 11. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Matching on Pre-Intervention Outcomes)

eTable 12. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Fixed Effects Model)

eTable 13. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Fixed Effects Model)

eTable 14. Differences in Pre-Acquisition Trends

eTable 15. Characteristics of HCA-Acquired Hospitals and Non-HCA Acquired Hospitals

eTable 16. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (HCA Hospitals)

eTable 17. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (HCA Hospitals)

eTable 18. Changes in Hospital Income and Use Measures (Non-HCA Hospitals)

eTable 19. Changes in Hospital Performance on Quality Measures (Non-HCA Hospitals)