Abstract

Introduction

Quality measures for colonoscopy such as adenoma detection rate (ADR) have been proposed to be surveilled for ensuring minimum standards. However, its direct measurement is time consuming and often neglected. Extrapolating ADR and other quality measures from polyp detection rate (PDR) can be a pragmatic alternative.

Objective

To determine quotients for estimating ADR and sessile serrated adenoma/polyp detection rate (SSA/P-DR) from PDR in an Australian cohort.

Methods

Consecutive adult patient colonoscopies during a 1-year period were retrospectively assessed in a single Australian tertiary endoscopy center. Adenoma detection quotient (ADQ) and SSA/P detection quotient (SSA/P-DQ) were defined as the division of ADR and SSA/P-DR by PDR, respectively. The primary outcome was the number of procedures to achieve a stable cumulative ADQ and SSA/P-DQ. Secondary outcomes included evaluation of ADQ and SSA/P-DQ in different subsets.

Results

In total, 2,657 colonoscopies were performed by 15 endoscopists in 2016. The ADR, SSA/P-DR, and PDR found were 32.2, 6.7, and 47.3%, respectively. The ADQ and SSA/P-DQ values found were 0.68 and 0.14, respectively. After approximately 500 procedures, both ADQ and SSA/P-DQ became stable. Interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the prediction of ADR from ADQ was excellent for all endoscopists that performed >177 procedures in that year (ICC 0.84).

Conclusions

ADQ and SSA/P-DQ values were consistent when over 500 procedures were analyzed. ADQ had an excellent correlation with ADR when >177 procedures per endoscopist were evaluated.

Keywords: Colonoscopy, Health metrics, Colonic polyps, Colonic neoplasms, Colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) ranks second in cancer deaths and third in incidence among all cancers in Australia. In 2018, there were approximately 17,000 new cases and 4,100 deaths due to CRC in the country [1]. According to the World Health Organization, a similar trend can be found throughout the world where CRC sits behind breast, prostate, and lung for incidence and behind lung and breast for mortality [2]. It is well known that CRC arises from either adenomas, SSA/polyps (SSA/Ps), or traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) [3, 4]. Screening colonoscopy and subsequent removal of premalignant colorectal lesions (CLs) have been shown to prevent CRC [5, 6, 7, 8]. As colonoscopy has become a standard procedure, quality measures have been investigated to monitor its efficacy. The adenoma detection rate (ADR) is defined as the number of patients with at least one adenoma divided by the number of screening colonoscopies is one of the most important quality measures. It has been shown that higher ADR is associated with lower mortality from CRC [9]. Currently, the Gastroenterological Society of Australia recommends an ADR of at least 25% [10]. In addition to monitoring adenomatous lesions, the focus has also shifted recently to serrated lesions. SSA/Ps have been shown to contribute to up to 30% of CRCs, albeit having a much lower prevalence [11]. The serrated pathway has a higher risk for the development of CRC than the traditional adenoma-carcinoma pathway [12, 13, 14]. This may also be due to the difficulty in its detection or the misdiagnosis either during colonoscopy or pathological evaluation [15, 16, 17]. It may hence be useful to calculate an SSA/polyp detection rate (SSA/P-DR) in addition to the ADR.

Although calculating both the ADR and SSA/P-DR makes intuitive sense and could and perhaps should be used as a measure of quality, both measures have not been used widely possibly due to the additional effort required (tracking histology of every single polyp removed). Some studies have proposed the use of a quotient based on the polyp detection rate (PDR) to promptly predict the ADR, negating the need to track the final histology [18, 19, 20, 21]. If consistent, the adoption of quotient values could enable swift calculation of ADR and SSA/P-DR for endoscopists and regulatory bodies, allowing for an effective performance evaluation tool. This study was designed to calculate and evaluate the stability of adenoma detection quotient (ADQ) and SSA/polyp detection quotient (SSA/P-DQ) over the period of one year.

Materials and Methods

Consecutive patients undergoing a colonoscopy at a tertiary Australian endoscopy center for any indication over a 12-month period were included (January to December 2016). This period was chosen based on the average number of colonoscopy procedures per year (∼2,500), which was a similar number to the numbers from a similar American study [20]. An existing electronic database was interrogated, and all procedures labeled as “colonoscopy” were initially retrieved. Then, the final procedural reports were identified and separated into positive colonoscopies (i.e., with at least one CL found) and negative colonoscopies (i.e., no CL found). Procedures initially labeled as colonoscopies and found to be flexisigmoidoscopies or ileoscopies in the procedure reports were excluded. All colonoscopies were performed or supervised by a Gastroenterologist or Surgeon accredited for performing colonoscopies by the Conjoint Committee for Recognition of Training in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Pathology reports were collected using a patient clinical information database. The colonoscopes used for the procedures were from the Olympus® 180 and 190 series. The “split” bowel preparation method was used for bowel preparation (i.e., 1 L of polyethylene glycol on the previous day and 1 L on the day of the procedure). As the bowel cleanliness status was expected to affect in a similar way all polyp detection metrics (i.e., PDR, ADR and SSA/P-DR), poor bowel preparation was recorded but not used as inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Individual consent was waived by the Northern Adelaide Local Health Network human research Ethics Committee (HREC/16/TQEH/283) due to the retrospective nature of the study. Data on indication, bowel preparation, age, gender, polyp histology, and location of the polyp within the colon was retrieved.

The primary outcome was to analyze the cumulative ADQ and SSA/P-DQ within the 1-year period to determine at what point the value became consistent (i.e., within 1 SD). Secondary outcomes included the comparison of predicted ADR and SSA/P-DR with the actual ADR and SSA/P-DR and the evaluation of ADQ and SSA/P-DQ for screening and specialty subsets.

ADR, SSA/P-DR, and PDR were defined as the proportion of colonoscopies with at least one adenoma, SSA/P and polyp, respectively. ADR and SSA/P-DR were based on both colonoscopy findings and histology report while PDR comprised of colonoscopy findings alone. ADQ and SSA/P-DQ were defined as the division of ADR and SSA/P-DR, respectively, by PDR.

The χ2 test was used for comparison of 2 proportions (for difference in detection rates between the first and last semesters) and the t test for comparison of means (for difference in quotients between the first and last trimesters). p value was considered significant when <0.05. Interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated with average measures and consistency of agreement through STATA software (©Copyright 1996–2019 StataCorp LLC); and interpreted according to Cicchetti et al. [22] (up to 0.40 = poor correlation; 0.40–0.59 = fair correlation; 0.60–0.74 = good correlation; and 0.75–1.00 = excellent correlation).

Results

In total, 2,498 patients underwent 2,657 colonoscopies between January and December 2016. These procedures were performed by 9 gastroenterologists and 6 surgeons from a tertiary Australian endoscopy center. About 49.8% were males, and the mean age of the entire cohort was 58.6 years (SD 14.6). The bowel preparation for the whole cohort was excellent or good in 63.3%, average or fair in 28.3%, and poor or inadequate in 8.0%. In 9 procedures (0.3%), information on the bowel cleanliness state was not available. About 47.5% of the cohort was over 60 years of age. The mean diameter of the 2,843 polyps detected was 7 mm (SD 7.7). Detailed histology can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Polyp histology

| Polyp histology | n (%) |

|---|---|

| No histology report | 251 (8.8) |

| No tissue for analysis | 25 (0.9) |

| Normal mucosa* | 127 (4.5) |

| Adenomas | 1,501 (52.8) |

| Tubular adenoma LGD | 1,236 (43.5) |

| Tubular adenoma HGD | 8 (0.3) |

| Tubulovillous adenoma LGD | 210 (7.4) |

| Tubulovillous adenoma HGD | 33 (1.2) |

| Villous adenoma LGD | 10 (0.4) |

| Villous adenoma HGD | 4 (0.1) |

| Serrated polyps | 829 (29.2) |

| Hyperplastic | 474 (16.7) |

| SSA/Ps without dysplasia | 323 (11.4) |

| SSA/Ps with dysplasia | 27 (1.0) |

| <B>TSA</B> | 5 (0.2) |

| Superficial cancer ** | 10 (0.4) |

| Invasive cancer | 70 (2.5) |

| Other (e.g., inflammatory, hamartoma)*** | 30 (1.1) |

Neoplastic lesions in bold.

Normal mucosa included melanosis coli.

Invasion of lamina propria invasion and muscularis mucosae, restricted to the submucosa.

Only one lesion classified as “other” was neoplastic (ganglioneuroma). LGD, low-grade dysplasia; HGD, high-grade dysplasia; SSA/Ps, sessile serrated adenoma/polyps; TSA, traditional serrated adenomas.

For the entire cohort, the ADR, SSA/P-DR, and PDR were 32.2, 6.7, and 47.3%, respectively. The difference in ADR, SSA/P-DR and PDR between the first and last semester was not statistically significant. The ADQ and SSA/P-DQ for the whole period was 0.68 and 0.14. This was not statistically different from when the ADQ and SSA/P-DQ were analyzed separately for the first and last trimesters and compared (Table 2).

Table 2.

ADQ and SSA/P-DQ for the whole year and first/last trimesters

| Period of measurement (n) | ADR, % | SSA/P-DR, % | PDR, % | ADQ, % | SSA/P-DQ, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full cohort (2,657) | 32.2 | 6.7 | 47.3 | 0.68 | 0.14 |

| First 3 months (705) | 34.6 | 7.4 | 51.1 | 0.68 | 0.14 |

| Last 3 months (570) | 31.9 | 6.7 | 47.7 | 0.67 | 0.14 |

ADR, adenoma detection rate; SSA/P-DR, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp detection rate; PDR, polyp detection rate; ADQ, adenoma detection quotient; SSA/P-DQ, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp detection quotient.

The mean ADQ varied from 0.56 to 0.77 throughout the year for all indications and was similar between Gastroenterologists and Surgeons (0.69 and 0.66, respectively). SSA/P-DQ varied from 0.06 to 0.23 with similar pattern. The SD was 0.03 for both quotients.

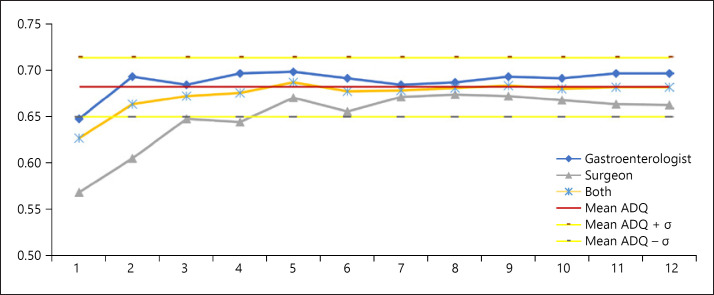

Looking at cumulative curves, it was observed that the ADQ stabilized after the 2nd month for the whole cohort and after the 5th month for both subsets (gastroenterologists and surgeons, Fig. 1). The number of procedures necessary to reach stability for the full cohort was between 300 and 500, depending on the subsets analyzed. SSA/P-DQ also reached stability within the first 5 months (Fig. 2); with <500 procedures. Using the same ADQ and SSA/P-DQ, the subanalysis of screening dataset reached stability at a later timeframe but with similar total number of procedures (onlline suppl. Fig. 1 and 2; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000505622).

Fig. 1.

Cumulative ADQ for all colonoscopies. ADQ, adenoma detection quotient.

Fig. 2.

Cumulative SSA/P-DQ for all colonoscopies. SSA/P-DQ, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp detection quotient.

In order to evaluate the internal validity of our quotients, individual PDR, ADR, and SSA/P-DR were calculated. As no individual endoscopist was able to reach 500 colonoscopies during 2016, we have used all endoscopists that surpassed the average number of procedures for that year (i.e., 177 colonoscopies). Six endoscopists reached this mark, 4 gastroenterologists (endoscopists 1–4) and 2 surgeons (endoscopists 5 and 6). The mean of procedures per endoscopist was 292 in this subset. For these endoscopists, the ADQ and SSA/P-DQ were calculated and lead to a maximum variability of 5% between predicted and actual ADR and of 3% between predicted and actual SSA/P-DR (Table 3). For endoscopists that did not reach these numbers (mean number of procedures = 101), the variation between predicted and actual ADR was 14% and between predicted and actual SSA/P-DR was 7% (online suppl. Table 2). For the first group, there was an excellent correlation between actual and predicted ADR (ICC 0.84) but a poor correlation between actual and predicted SSA/P-DR (ICC 0.04). However, when looking at only Gastroenterologists, this correlation was excellent (ICC 0.83). As no single endoscopist had done >100 screening colonoscopies in 2016, the pooled ADR and SSA/P-DR was analyzed for the screening subset. This showed excellent and good correlation between predicted and actual detection rates. The ICC for screening colonoscopies was 0.98 for ADR and 0.67 for SSA/P-DR (Table 4).

Table 3.

Individual results for predicted and actual adenoma and SSA/P-DR (high numbers group − all indications)

| Endoscopist | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 308 | 365 | 224 | 315 | 248 | 291 |

| PDR, % | 41.90 | 59.20 | 42.40 | 43.80 | 46.80 | 56.40 |

| Predicted ADR, % | 28.50 | 40.20 | 28.80 | 29.80 | 31.80 | 38.30 |

| Actual ADR, % | 30.50 | 45.20 | 26.80 | 31.40 | 26.60 | 38.80 |

| Actual-predicted ADR gap, % | 2.00 | 5.00 | −2.10 | 1.60 | −5.20 | 0.50 |

| Predicted SSA/P-DR, % | 5.90 | 8.30 | 5.90 | 6.10 | 6.50 | 7.90 |

| Actual SSA/P-DR, % | 7.10 | 11.20 | 6.70 | 8.60 | 5.60 | 5.20 |

| Actual-predicted SSA/P-DR gap, % | 1.30 | 2.90 | 0.80 | 2.40 | −0.90 | −2.70 |

ADR, adenoma detection rate; SSA/P-DR, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp detection rate; PDR, polyp detection rate.

Table 4.

Pooled screening predicted and actual adenoma and SSA/P-DR

| Screening colonoscopies | Gastro | Surgeon | All cohort |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 339 | 219 | 558 |

| PDR, % | 50.10 | 43.40 | 47.50 |

| Predicted ADR, % | 34.10 | 29.50 | 32.30 |

| Actual ADR, % | 36.30 | 30.60 | 34.10 |

| Actual-predicted ADR gap, % | 2.20 | 1.10 | 1.80 |

| Predicted SSA/P-DR, % | 7.00 | 6.10 | 6.60 |

| Actual SSA/P-DR, % | 6.50 | 5.50 | 6.10 |

| Actual-predicted SSA/P-DR gap, % | −0.50 | −0.60 | −0.60 |

ADR, adenoma detection rate; SSA/P-DR, sessile serrated adenoma/polyp detection rate; PDR, polyp detection rate.

Discussion/Conclusion

One of the major quality measures presently proposed for monitoring endoscopists' performance is the ADR. Serrated polyps are an important precursor of CRC and hence another metric, the sessile SSA/P-DR, has been proposed. In order to track these metrics, a post-colonoscopy pathology assessment is required. This is time consuming and has been one of the main deterrent factors for widespread use of ADR and SSA/P-DR. The possibility of extrapolating the ADR and SSA/P-DR from a simple metric (PDR) could provide a more pragmatic alternative. Currently, no consensus values exist for the ADQ and the SSA/P-DQ due to potential for variation in different settings. The ADQ found in our study (i.e., 0.68) was consistent with what was found in recent studies from Murchie et al. [21] (i.e., 0.66–0.67) and Elhanafi et al. [20] (i.e., 0.68). This lends support to the use of this quotient in Australia.

In our study, the presence of a polyp in the colonoscopy was used for calculation of the PDR rather than the histology report, what is consonant with the concept of using PDR for predicting ADR. Therefore, even though 8.8% of the detected polyps did not have a histology report (mainly for not being resected due to benign features such as diminutive rectosigmoid HPs), this were still used as positive colonoscopies for calculating PDR. On the other hand, only histologically confirmed adenomas and SSA/Ps were used for calculating ADR and SSA/P-DR, respectively.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study describing the SSA/P-DQ. Although the study has shown a consistent internal validity similar to the ADQ, the correlation between predicted and actual SSA/P-DR was excellent only for gastroenterologists. This might be due to the relative lower SSA/P prevalence. Even with only 3% predicted-actual gap, this represented a wide relative variation and led to an important impact on correlation. Further studies are required to validate the usefulness of SSA/P-DQ, bearing in mind the diversity in SSA/P endoscopy and pathology diagnoses.

ADQ and SSA/P-DQ derived from the whole cohort were able to predict ADR and SSA/P-DR for individual endoscopists regardless of their specialty (i.e., Gastroenterology or Surgery). Therefore, the nonstatistically significant difference for the ADQ and SSA/P-DQ of the individual subsets does not seem to affect the use of detection quotients in endoscopy. We hypothesize that this minor difference might be a product of a slightly higher detection of non-neoplastic polyps by the surgeons, or it might be due to random variation.

In a study from Amsterdam on 1,426 screen-naïve participants, the prevalence of HPs, SSA/Ps and TSAs was 23.8, 4.8, and 0.1%, respectively. Of the 1,782 specimens, 41.8% (744) were found to be SPs. Of those, 14.9% (111) were SSA/Ps [23]. These findings did not deviate much from the findings of our cohort where the overall prevalence of SSA/Ps was 12.4%. Among SPs, 57.2% were classified as HPs, 42.2% as SSA/Ps and 0.6% as TSAs. A Korean study found SSA/Ps in 3.1% of 1,375 asymptomatic patients over 50 years of age. The percentage of patients with adenomas was 43.5% [24]. These percentages were expected to be even higher as they evaluated only proximal colon polyps. In another study from the East, only 8.7% of CRCs were associated with the serrated pathway [25]. In addition to the setting, the time when the study is performed also matters. A study at the Mayo Clinic based on data from 2005 to 2007 found only 2.9% of polyps was SSA/Ps [26]. In contrast, another study in the USA found an overall prevalence of 8.1% and a prevalence of 15.8% in the last year of the study − 2012 [27]. It appears that the prevalence of SSA/Ps prevalence is higher in more recent studies. This may be a result of increased awareness of the entity and/or due to systematic removal of adenomas in the past, which could lead to a relative increase in SSA/P abundance.

The literature as well as our cohort support the belief of a higher SSA/P prevalence is present in western countries [28, 29, 30, 31, 32]. From the 701 diminutive RS polyps with confirmed tissue on histology, 305 were neoplastic (43.5%). Two hundred and twenty-six were adenomas (2 with high grade dysplasia), 77 SSA/Ps (3 with dysplasia) and 2 TSAs. Among serrated lesions, HPs corresponded to 81.4% of the diminutive polyps in the RS while SSA/Ps represented 18.2% (online suppl. Table 1). The SSA/P-DQ would most likely have greater applicability in Western countries. However, it is important to note that this study was designed focusing on detection quotients rather than detection rates. Therefore, the inclusion of patients with different medical backgrounds (e.g., previous CRC, variable family history of CRC and fecal occult blood test positive) warrants a critical view on the reported ADR and SSA/P-DR found.

A limitation of this study is the relatively small number of procedures per individual endoscopist. This is however an actual reflection of procedures performed by a range of endoscopists in a tertiary public hospital in the country. Nevertheless, when looking at endoscopists with >177 procedures, the prediction was accurate with an actual-predicted gap of at most 5% for ADR and 3% for SSA/P-DQ. A conservative policy could then be used to account for this variability. Future research for validation of these findings in other Australian centers is warranted.

In conclusion, ADQ and SSA/P-DQ values were consistent when over 500 procedures were analyzed. ADQ had an excellent correlation with ADR when >177 procedures per endoscopist were evaluated. The quotient values proposed for ADQ and SSA/P-DQ could be used for an easier calculation of endoscopists' ADR (0.68 × PDR) and SSA/P-DR (0.14 × PDR), potentially allowing for better evaluation of this important quality measure. As the Australian guidelines recommend that each Endoscopist has an ADR of at least 25%, a minimum PDR of 40% could be used as a surrogate marker. If this is not met, calculation of the actual ADR would be necessary. In addition, after an ideal SSA/P-DR is determined, SSA/P-DQ could then be used to measure this quality indicator.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (TQEH/LMH/MH) under the reference number HREC/16/TQEH/283. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the Committee has waived the requirement of individual written consents. This Committee is constituted in accordance with the NHMRC National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007) and incorporating all updates.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This is a self-initiated study. No funding was received.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and complied with author guidelines and contributed to this manuscript as described: L.Z.C.T.P., A.D.B., and R.S. conceptualized and designed the study. R.S. was responsible for the study supervision. L.Z.C.T.P., S.K., and A.O. were involved in the data extraction. L.Z.C.T.P., G.S., K.R., and S.E. were involved in the statistical analysis. L.Z.C.T.P., K.R., G.S., S.K., and A.O. drafted the manuscript. L.Z.C.T.P., M.N., T.Y., A.R., Y.H., and M.F. were involved in the interpretation of the results. A.D.B., R.S., M.N., T.Y., S.E., A.R., Y.H., and M.F. critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

References

- 1.AIHW . National Bowel Cancer Screening Program: monitoring report 2018. AIHW; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Nov;68((6)):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bettington M, Walker N, Clouston A, Brown I, Leggett B, Whitehall V. The serrated pathway to colorectal carcinoma: current concepts and challenges. Histopathology. 2013 Feb;62((3)):367–86. doi: 10.1111/his.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Terada T. Histopathologic study of the rectum in 1,464 consecutive rectal specimens in a single Japanese hospital: II. malignant lesions. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6((3)):385–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Verbeek AL, van Oijen MG, Laheij RJ, Fockens P, et al. Colorectal cancer screening comparing no screening, immunochemical and guaiac fecal occult blood tests: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Int J Cancer. 2011 Apr;128((8)):1908–17. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He X, Hang D, Wu K, Nayor J, Drew DA, Giovannucci EL, et al. Long-term Risk of Colorectal Cancer After Removal of Conventional Adenomas and Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology. 2019 Jul;:S0016-5085(19)41086-X. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helsingen LM, Vandvik PO, Jodal HC, Agoritsas T, Lytvyn L, Anderson JC, et al. Colorectal cancer screening with faecal immunochemical testing, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy: a clinical practice guideline. BMJ. 2019 Oct;367:l5515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l5515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JK, Jensen CD, Levin TR, Doubeni CA, Zauber AG, Chubak J, et al. Long-term Risk of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death After Adenoma Removal in a Large, Community-based Population. Gastroenterology. 2019 Oct 4; doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR, Zhao WK, Lee JK, Doubeni CA, et al. Adenoma detection rate and risk of colorectal cancer and death. N Engl J Med. 2014 Apr;370((14)):1298–306. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chittleborough TJ, Kong JC, Guerra GR, Ramsay R, Heriot AG. Colonoscopic surveillance: quality, guidelines and effectiveness. ANZ J Surg. 2018 Jan;88((1-2)):32–8. doi: 10.1111/ans.14141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laird-Fick HS, Chahal G, Olomu A, Gardiner J, Richard J, Dimitrov N. Colonic polyp histopathology and location in a community-based sample of older adults. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016 Aug;16((1)):90. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0497-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bettington M, Walker N, Rosty C, Brown I, Clouston A, McKeone D, et al. Clinicopathological and molecular features of sessile serrated adenomas with dysplasia or carcinoma. Gut. 2015 Oct; doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erichsen R, Baron JA, Hamilton-Dutoit SJ, Snover DC, Torlakovic EE, Pedersen L, et al. Increased Risk of Colorectal Cancer Development Among Patients With Serrated Polyps. Gastroenterology. 2016;150((4)):895–902.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melson J, Ma K, Arshad S, Greenspan M, Kaminsky T, Melvani V, et al. Presence of small sessile serrated polyps increases rate of advanced neoplasia upon surveillance compared with isolated low-risk tubular adenomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Aug;84((2)):307–14. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payne SR, Church TR, Wandell M, Rösch T, Osborn N, Snover D, et al. Endoscopic detection of proximal serrated lesions and pathologic identification of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps vary on the basis of center. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014 Jul;12((7)):1119–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee J, Park SW, Kim YS, Lee KJ, Sung H, Song PH, et al. Risk factors of missed colorectal lesions after colonoscopy. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017 Jul;96((27)):e7468. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mandaliya R, Baig K, Barnhill M, Murugesan V, Som A, Mohammed U, et al. Significant Variation in the Detection Rates of Proximal Serrated Polyps Among Academic Gastroenterologists, Community Gastroenterologists, and Colorectal Surgeons in a Single Tertiary Care Center. Dig Dis Sci. 2019 Sep;64((9)):2614–21. doi: 10.1007/s10620-019-05664-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis DL, Rodriguez-Correa DT, Buchner A, Harewood GC, Wallace M. Application of a conversion factor to estimate the adenoma detection rate from the polyp detection rate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Mar;73((3)):493–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel NC, Islam RS, Wu Q, Gurudu SR, Ramirez FC, Crowell MD, et al. Measurement of polypectomy rate by using administrative claims data with validation against the adenoma detection rate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Mar;77((3)):390–4. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elhanafi S, Ortiz AM, Yarlagadda A, Tsai C, Eloliby M, Mallawaarachchi I, et al. Estimation of the Adenoma Detection Rate From the Polyp Detection Rate by Using a Conversion Factor in a Predominantly Hispanic Population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015 Aug;49((7)):589–93. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murchie B, Tandon K, Zackria S, Wexner SD, O'Rourke C, Castro FJ. Can polyp detection rate be used prospectively as a marker of adenoma detection rate? Surg Endosc. 2018 Mar;32((3)):1141–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5785-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cicchetti DV. Butcher, James N. & Nelson, Linda D. Guidelines, Criteria, and Rules of Thumb for Evaluating Normed and Standardized Assessment Instruments in Psychology. Psychol Assess. 1994;6((4)):7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hazewinkel Y, de Wijkerslooth TR, Stoop EM, Bossuyt PM, Biermann K, van de Vijver MJ, et al. Prevalence of serrated polyps and association with synchronous advanced neoplasia in screening colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2014 Mar;46((3)):219–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1358800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee CK, Kim YW, Shim JJ, Jang JY. Prevalence of proximal serrated polyps and conventional adenomas in an asymptomatic average-risk screening population. Gut Liver. 2013 Sep;7((5)):524–31. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2013.7.5.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu H, Qin H, Huang Z, Li S, Zhu X, He J, et al. Clinical significance of programmed death ligand-1 (PD-L1) in colorectal serrated adenocarcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015 Aug;8((8)):9351–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gurudu SR, Heigh RI, De Petris G, Heigh EG, Leighton JA, Pasha SF, et al. Sessile serrated adenomas: demographic, endoscopic and pathological characteristics. World J Gastroenterol. 2010 Jul;16((27)):3402–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i27.3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abdeljawad K, Vemulapalli KC, Kahi CJ, Cummings OW, Snover DC, Rex DK. Sessile serrated polyp prevalence determined by a colonoscopist with a high lesion detection rate and an experienced pathologist. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Mar;81((3)):517–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.IJspeert JE, de Wit K, van der Vlugt M, Bastiaansen BA, Fockens P, Dekker E, JE IJ Prevalence, distribution and risk of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps at a center with a high adenoma detection rate and experienced pathologists. Endoscopy. 2016 Aug;48((8)):740–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bettington M, Walker N, Rahman T, Vandeleur A, Whitehall V, Leggett B, et al. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas in contemporary outpatient colonoscopy practice. Intern Med J. 2017 Mar;47((3)):318–23. doi: 10.1111/imj.13329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohki D, Tsuji Y, Shinozaki T, Sakaguchi Y, Minatsuki C, Kinoshita H, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma detection rate is correlated with adenoma detection rate. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2018 Mar;10((3)):82–90. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v10.i3.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pyo JH, Ha SY, Hong SN, Chang DK, Son HJ, Kim KM, et al. Identification of risk factors for sessile and traditional serrated adenomas of the colon by using big data analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 May;33((5)):1039–46. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crockett SD, Nagtegaal ID. Terminology, Molecular Features, Epidemiology, and Management of Serrated Colorectal Neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2019 Oct;157((4)):949–966.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data

Supplementary data