Abstract

Objective

This study on the prevalence of diabetic nephropathy (DN) and coexistence of non-diabetic renal disease (NDRD) in a cohort of 255 non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) patients aims to determine the value of performing renal biopsies in these patients and elucidate the factors which could affect their progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).

Methods

Among 255 NIDDM patients, 93 had DN alone, 69 had NDRD alone, and the remaining 93 had DN plus NDRD (mixed group). The indications for renal biopsy were based on clinical suspicion of superimposed NDRD, including heavy or rapidly increasing proteinuria, renal impairment even though diabetes is of relatively short duration, rapidly declining renal function, and presence of hematuria with dysmorphic red blood cells suggesting presence of glomerulonephritis.

Results

The following were predictors of ESRD: high systolic BP at biopsy, longer duration of diabetes, heavy proteinuria, and presence of diabetic retinopathy. Comparing patients in the NDRD group with the DN group and the mixed group, the NDRD group had lower serum creatinine and higher eGFR with lower urinary proteinuria and higher serum albumin at presentation and on follow-up. Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules were associated with a poorer prognosis leading to a higher occurrence of ESRD among patients with DN.

Conclusion

Renal biopsy is of value in indicating the prognosis of NIDDM patients with DN based on the diabetic lesions. For NIDDM patients with atypical course and suspicion of associated NDRD, a renal biopsy would enable us to diagnose the underlying NDRD and offer appropriate therapy. Most nephrologists would consider renal biopsy for an NIDDM patient based on clinical indications like atypical clinical course and suspicion of an associated NDRD, but they would not perform a routine renal biopsy like for a CKD patient, unless it is for a research indication.

Keywords: Diabetic nephropathy, Renal biopsy, Non-diabetic renal disease, Retinopathy

Introduction

Diabetes is the commonest cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in many developed countries [1, 2]. There is no cure for diabetic nephropathy (DN), and many patients develop complications including cardiovascular morbidity and mortality long before they require renal replacement therapy [2]. Most nephrologists would not routinely perform renal biopsy for non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) patients unless these patients have an atypical clinical course or there is a suspicion of their having associated non-diabetic renal disease (NDRD). In a recent pooled meta-analysis of 48 studies by Fiorentino et al. [3], comprising 4,876 patients, the prevalence of DN, NDRD, and mixed forms ranged from 6.5 to 94%, 3 to 82.9%, and 4 to 45.5%, respectively [3]. About 50% of these patients with NIDDM have another form of kidney disease (NDRD), and the majority of these studies were from Asian countries where IgA nephritis was more common compared to other countries [1, 3].

In Singapore [4] and the surrounding countries like Malaysia [5], Taiwan [6, 7], India [8], and Australia [9, 10], diabetes is the commonest secondary glomerulonephritis (GN) in clinical practice and also the commonest cause of ESRD. However, not all patients with a clinical diagnosis of DN are subjected to renal biopsies as many nephrologists do not consider that a renal biopsy will alter the course of their therapy for diabetics compared to patients with lupus nephritis who are usually biopsied as the biopsy data are required in the staging and management of their renal disease. This practice is changing as more nephrologists nowadays are performing renal biopsies on patients with diabetes as many diabetics are now found to have superimposed NDRD which is more amenable to therapy [3, 11].

This study on the prevalence of DN and coexistence of NDRD in a cohort of 255 NIDDM patients aims to determine the value of performing renal biopsies in these patients and elucidate the factors which could affect their progression to ESRD. We seek to establish the factors which determine this progression in both DN and NDRD patients. Nowadays, if a patient with diabetes is suspected of having an NDRD coexisting with DN, many would favor a renal biopsy to diagnose an NDRD which could be amenable to therapy. This is especially so if there is new onset of heavy proteinuria or rapid deterioration of renal function in such patients.

However, the rates of renal biopsies performed in these patients with NIDDM are variable ranging from 12 to 80% [12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23] depending on the practice in various centers and their varying indications for renal biopsy in such patients.

In a paper by Chang et al. [11], among 119 patients with NIDDM who had renal biopsies done, 34 with NDRD were treated with steroids and immunosuppressant, and 23 (67.6%) had recovery with partial or complete remission of proteinuria and recovery of renal failure. This shows the importance of performing renal biopsies in NIDDM patients suspected of having an NDRD. We believe that in many centers today this is the standard practice in NIDDM patients suspected of having an associated NDRD.

In our present study, we analyzed 255 patients with NIDDM who were seen at the Singapore General Hospital over the past 20 years. This is a single-center study. Our main aim was to assess the value of renal biopsy in NIDDM patients and the impact of NDRD amongst patients with NIDDM and to establish the factors which affect their progression to ESRD. There were 3 groups of patients in this cohort, those with DN alone, those with NDRD alone, and those in the mixed group with DN and coexisting NDRD. Each of these 3 groups may have differing rates and factors influencing their progression to ESRD. For those with NDRD, a definitive diagnosis based on renal biopsy findings may help to support therapy with steroids or other immunosuppressive drugs depending on the type of GN as this may prove helpful in reversing or preventing renal failure. As for those with DN, a renal biopsy may help to stage the degree of renal involvement and determine the prognosis with regard to ESRD.

Materials and Methods

We have maintained a renal biopsy registry over the past 4 decades, and in the course of the last decade we have seen an increase in the numbers of diabetic patients biopsied for various indications.

In the 1st decade, only 12% of patients were biopsied for secondary GN, and these have increased to 18, 35, and 39% in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th decades, >3-fold increase between the 4th and the 1st decade. For all 4 decades, the commonest indication for biopsy was lupus nephritis for purposes of diagnosis, management, and prognosis. In the 4th decade, lupus nephritis accounted for 56% of all secondary GN, while diabetes accounted for 36%, second commonest indication. In the first 2 decades, we did not usually biopsy patients with diabetes unless they had associated hematuria to suggest an underlying GN, but during the past decade, more patients with diabetes were biopsied when they had massive proteinuria to exclude other associated glomerular diseases and to confirm the histological presence of DN as many patients with a clinical diagnosis of diabetes have been found to have associated NDRD [24].

In the 3rd and 4th decades, based on the renal biopsy registry records, 255 patients with NIDDM had renal biopsies performed. These 255 patients were included in the present study. The inclusion criteria were adequate biopsy data and availability of initial and long-term follow-up clinical and laboratory data for analyses. This is an academic study supported by Singhealth Cluster with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval − CIRB Ref. No. 3147 E, and the study protocol has been approved by the Institution's IRB committee on human research and conforms to institutional standards. Waiver of patient consent was approved for this retrospective medical records review.

All patients had type 2 diabetes as defined by the World Health Organization and the American Diabetes Association [25, 26]. In these 255 NIDDM patients, 93 had DN alone, 69 had NDRD alone, and the remaining 93 had DN plus NDRD (mixed group). The indications for renal biopsy were based on clinical suspicion of superimposed NDRD, including heavy or rapidly increasing proteinuria, renal impairment even though diabetes is of relatively short duration, rapidly declining renal function, and presence of hematuria with dysmorphic red blood cells suggesting the presence of GN. Renal biopsy was performed by percutaneous needle biopsy and specimens of biopsy tissue were sent for light microscopy, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy. The diagnosis of DN was based on the presence of glomerular lesions like mesangial expansion, diffuse intercapillary glomerulosclerosis, Kimmelstiel-Wilson (KW) nodules, basement membrane thickening, and exudative lesions, such as fibrin cap, capsular drop or arteriolar hyalinosis, and arteriolar sclerosis [25, 27]. NDRD was defined by the presence of histological lesions different from the above mentioned for DN and included GN like IgA nephritis, membranous GN, focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), and other renal diseases.

All patients had the following investigations performed prior to renal biopsy: full blood count including hemoglobin, urine microscopy, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), urinary protein excretion, fasting blood glucose, hemoglobin A1c, and ultrasound examination of the kidneys. Diabetic retinopathy was diagnosed by direct ophthalmoscopy and fluorescence performed by an ophthalmologist. Hypertension was defined by systolic blood pressure (BP) of >140 mm Hg and diastolic BP of >90 mm Hg. ESRD was defined as eGFR of <15 mL/min/year.

Statistical Methods

All values are expressed as mean ± SD or as percentages. SPSS version 25 for Windows was used for all analysis. Results were expressed as mean ± SD or median (range) or count (%). For univariate analysis, Pearson's χ2 test was used for comparing categorical data and ANOVA for comparing numeric data between the 3 groups (DN alone, NDRD alone, and mixed group). ANOVA was followed by multiple comparisons with the Student-Newman-Keuls range test whenever statistical significance was found between the 3 groups. Independent predictors of ESRD were determined by Cox regression, including all covariates with a p value of <0.05 on univariate analysis. To identify risk factors for ESRD, which was the end point of this study, multivariate analyses and Cox regression were performed. Kaplan-Meier analysis and log-rank test were used to compare the difference in cumulative renal survival according to the risk factors identified on Cox regression. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 255 patients with NIDDM were included in the study. The demographics, clinical profile, and laboratory data of these patients divided into 3 groups are shown in Table 1 which compares the 3 groups, the DN alone group (group 1, n = 93), the NDRD alone group (group 2, n = 69), and the mixed (DN and NDRD) group (group 3, n = 93). The NDRD group was older (p < 0.001). There were no differences in the duration of follow-up, gender, ethnicity, and body mass index between the different races. The NDRD group had lower systolic BP on biopsy (p < 0.03), less DN (p < 0.05), and less retinopathy (p < 0.05) compared to the other 2 groups. There were no differences in the kidney sizes between the 3 groups. Laboratory data showed that group 2 had lower serum creatinine on follow-up (p < 0.001), higher eGFR on follow-up (p < 0.05), lower total cholesterol (p < 0.001), lower LDL cholesterol (p < 0.002), lower HbA1c (p < 0.04), more RBCs on urine microscopy at renal biopsy (p < 0.02), and less proteinuria (p < 0.01) with higher serum albumin (p < 0.05) compared to group 1 and group 3.

Table 1.

Demographics, clinical profile and laboratory data of 255 patients divided into 3 groups (n = 255)

| Variable | Group 1 (n = 93) | Group 2 (n = 69) | Group 3 (n = 93) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years1 | 52.5±11.8 | 60.1±10.9 | 56.8±11.1 | <0.001 |

| Gender, male:female, % | 54.8:45.2 | 66.7:33.3 | 58.1:41.9 | NS |

| Male gender, n (%) | 51 (54.8) | 46 (66.6) | 54 (58.1) | NS |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Chinese | 72 (77.4) | 49 (71.0) | 73 (78.5) | <0.02 |

| Malay | 15 (16.1) | 7 (10.1) | 17 (18.3) | |

| Indian | 4 (4.3) | 7 (10.1) | 3 (3.2) | |

| Others | 2 (2.2) | 6 (8.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Body mass index | 26.7±5.0 | 27.6±5.6 | 27.0±4.8 | NS |

| Duration of follow-up, months | 36.2±24.3 | 41.6±31.5 | 42.9±24.8 | NS |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 14.1±8.6 | 12.1±8.3 | 13.8±8.3 | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg1* | 151±26 | 139±23 | 149±22 | <0.03 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg1 | 74±10 | 74±13 | 76±12 | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg2 | 144±27 | 138±19 | 140±25 | NS |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg2 | 71±10 | 70±11 | 71±12 | NS |

| Presence of diabetic nephropathy1 | 82 (88.2) | 15 (21.7) | 68 (73.1) | <0.05 |

| Presence of retinopathy1 | 39 (41.9) | 4 (5.8) | 24 (25.8) | <0.05 |

| Presence of hypertension1 | 84 (90.3) | 62 (89.9) | 86 (92.5) | NS |

| Left kidney size, cm1 | 11.4±1.2 | 11.1±1.3 | 11.2±1.1 | NS |

| Right kidney size, cm1 | 11.3±1.0 | 10.9±1.2 | 11.1±1.1 | NS |

| Ultrasound kidney abnormality1 | 29 (32.6) | 23 (44.2) | 38 (45.2) | NS |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL1 | 11.5±2.1 | 12.1±2.2 | 11.3±2.0 | NS |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L1 | 181.1±104.7 | 178.3±118.2 | 204.1±136.2 | NS |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L2* | 359.4±269.1 | 239.2±233.4 | 389.7±275.5 | <0.001 |

| eGFR1 | 47.9±34.1 | 52.7±36.6 | 43.2±30.5 | NS |

| eGFR2* | 30.2±28.5 | 46.6±31.7 | 27.7±27.6 | <0.05 |

| Serum albumin, g/L1 | 29.4±7.4 | 32.4±9.3 | 31.6±7.0 | <0.05 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L1 | 6.3±2.0 | 5.2±1.8 | 5.3±1.4 | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol LDL, mmol/L1 | 3.9±2.0 | 3.1±1.4 | 3.2±1.1 | <0.002 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, %1 | 7.6±1.9 | 6.9±1.1 | 7.6±1.9 | <0.04 |

| Red blood cells1 | 40.3±88.5 | 205.4±533.8 | 112.4±381.6 | <0.02 |

| Presence of RBCs3, n (%)1 | 72 (77.4) | 51 (73.9) | 58 (63.7) | NS |

| Urinary proteins1* | 8.8±5.7 | 5.8±5.6 | 7.7±5.6 | <0.01 |

| Urinary proteins2* | 7.4±5.9 | 3.0±4.2 | 5.7±5.5 | <0.05 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or number of patients (%). DN, diabetic nephropathy; NDRD, non-diabetic renal diseases; group 1, DN only; group 2, NDRD only; group 3, mixed (DN and NDRD).

Values were taken at biopsy.

Values were taken after biopsy.

Presence of RBCs is considered yes when RBCs is >3.

Multivariate and Cox regression analysis was performed and gave significant value for systolic blood pressure, serum creatinine, eGFR, and urinary proteins.

Histopathology of NDRD

Table 2 shows the distribution of the histopathological diagnosis among groups 2 and 3. The commonest type of GN was FSGS, and this was significantly greater in group 3 compared to group 2 (p < 0.00001). The increased FSGS in group 3 could be due to the presence of DN. IgA nephritis was the second commonest GN, and this was significantly greater in group 2. Other types of GN like membranous GN and minimal change disease, although they occurred more frequently in group 2, they were not significantly more frequent compared with group 3. Of note was the increased presence of acute tubular necrosis in group 3 (p < 0.003) probably due to the associated DN. Interstitial nephritis and malignant nephrosclerosis occurred more frequently in group 3, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Table 2.

Histopathological diagnosis: distribution among groups 2 and 3

| Pathologic diagnosis | Group 2 (n = 69) | Group 3 (n = 93) | Total (n = 162) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgA nephropathy | 13 (8.0) | 6 (3.7) | 19 (11.7) | <0.05 |

| Membranous nephropathy | 10 (6.2) | 5 (3.1) | 15 (9.3) | NS |

| Focal segmented glomerulosclerosis | 25 (15.4) | 61 (37.7) | 86 (53.1) | <0.00001 |

| Minimal change disease | 6 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 6 (3.7) | NS |

| Mesangiocapillary proliferative GN | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | 4 (2.4) | NS |

| Interstitial nephritis | 0 (0) | 5 (3.1) | 5 (3.1) | NS |

| Malignant nephrosclerosis | 0 (0) | 6 (3.7) | 6 (3.7) | NS |

| Vasculitis | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.2) | NS |

| Postinfectious GN | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | NS |

| Acute tubular necrosis | 1 (0.6) | 7 (4.3) | 8 (4.9) | <0.003 |

| Osmotic nephrosis | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | NS |

| Others | 9 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 9 (5.6) | NS |

Data are presented as number of patients (%). DN, diabetic nephropathy; NDRD, non-diabetic renal diseases; group 2, NDRD only; group 3, mixed (DN and NDRD).

Histopathology of DN

Table 3 shows the distribution of the histopathological diagnosis for DN among the patients in group 1 and those in group 3. The commonest type of DN lesion was KW nodule, which occurred more often in group 1 (75%; p < 0.0001). The next commonest lesion was mesangial expansion, which was more common in group 3 (15%; p < 0.0001). Basement membrane thickening occurred more commonly in group 3, (8%; p < 0.0001) compared to group 1. Arteriolar sclerosis also occurred more commonly in group 3 (37.1%; p < 0.0001) compared to group 1. Combined lesions of arteriolar hyalinosis and arteriolar sclerosis were present in 6% of group 1 and 4.9% of group 3, but this difference was not significant.

Table 3.

Distribution of histopathological diagnosis for diabetic nephropathy in groups 1 and 3

| Types of DN lesions | Group 1 (n = 92) | Group 3 (n = 91) | Total (n = 183) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesangial expansion | 4 (2.2) | 24 (13.1) | 28 (15.3) | <0.0001 |

| Diffuse intercapillary | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | NS |

| Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodule | 87 (47.5) | 50 (27.3) | 137 (74.9) | <0.0001 |

| Basement membrane thickening | 1 (0.5) | 13 (7.1) | 14 (7.7) | <0.0001 |

| Fibrin cap | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS |

| Capsular drop | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (1.1) | NS |

| Arteriolar hyalinosis | 0 (0) | 6 (3.3) | 6 (3.3) | NS |

| Arteriolar sclerosis | 13 (7.1) | 45 (24.6) | 58 (31.7) | <0.0001 |

| Arteriolar hyanlinosis and sclerosis | 11 (6.0) | 9 (4.9) | 20 (10.9) | NS |

Data not reported for 3 patients and excluded in the above table. Data are presented as number of patients (%). DN, diabetic nephropathy; NDRD, non-diabetic renal diseases; group 1, DN only; group 3, mixed (DN and NDRD).

Comparing Patients with and without ESRD in the 3 Groups

Table 4 compares the patients with ESRD versus those with non-ESRD in the 3 groups separately to determine if there were any differences in the profile of the ESRD patients in the 3 groups.

Table 4.

Comparison between ESRD and non-ESRD patients in the 3 separate groups

| Variable | Group 1 (n = 93) |

Group 2 (n = 66) |

Group 3 (n = 93) |

p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRD | non-ESRD | p value | ESRD | non-ESRD | p value | ESRD | non-ESRD | p value | ||

| Age, years1 | 51.2±10.6 | 53.3±12.5 | NS | 60.8±11.4 | 60.2±10.9 | NS | 54.5±12.4 | 58.8±9.6 | NS | <0.04 |

| Gender male:female, % | 25.8:12.9 | 29.0:32.3 | NS | 13.0:4.3 | 49.3:29.0 | NS | 25.8:21.5 | 32.3:20.4 | NS | NS |

| Male gender, n (%) | 24 (25.8) | 27 (29.0) | NS | 9 (13.0) | 34 (49.3) | NS | 24 (25.8) | 30 (32.3) | NS | NS |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||||

| Chinese | 29 (31.2) | 43 (46.2) | NS | 9 (13.0) | 40 (58.0) | NS | 34 (36.6) | 39 (41.9) | NS | NS |

| Malay | 7 (7.5) | 8 (8.6) | 2 (2.9) | 5 (7.2) | 8 (8.6) | 9 (9.7) | ||||

| Indian | 0 (0) | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0) | 7 (10.1) | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | ||||

| Others | 0 (0) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | ||||

| Body mass index | 26.9±5.4 | 26.5±4.8 | NS | 26.2±6.8 | 27.8±5.4 | NS | 27.0±5.4 | 27.0 ±4.3 | NS | NS |

| Duration of follow-up, months | 40.4±24.4 | 33.5±24.1 | NS | 50.3±39.4 | 40.4±29.4 | NS | 48.8±26.0 | 37.8±22.8 | <0.04 | NS |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 14.7±7.5 | 13.8±9.3 | NS | 12.5±7.7 | 12.0±8.5 | NS | 15.1±8.6 | 12.7±7.9 | NS | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg1 | 148.3±34.2 | 151.5±21.1 | NS | 148.3±18.2 | 136.6±22.8 | NS | 155.8±25.6 | 143.3±17.6 | <0.04 | <0.04 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg1 | 74.4±13.6 | 73.9±8.7 | NS | 76.7±12.2 | 73.0±12.0 | NS | 79.1±12.8 | 73.6±11.4 | NS | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg2 | 145.2±25.4 | 143.5±28.0 | NS | 144.1±20.7 | 137.2±18.2 | NS | 142.5±24.6 | 138.5±24.7 | NS | NS |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg2 | 71.7±8.6 | 71.2±11.2 | NS | 68.7±10.6 | 70.2±11.0 | NS | 72.4±12.1 | 70.7±11.4 | NS | NS |

| Presence of diabetic nephropathy1 | 30 (32.3) | 52 (55.9) | NS | 2 (2.9) | 13 (18.8) | NS | 35 (37.6) | 33 (35.5) | NS | NS |

| Presence of retinopathy1 | 14 (15.0) | 25 (26.9) | NS | 0 (0) | 4 (5.8) | NS | 14 (15.1) | 10 (10.8) | NS | NS |

| Presence of hypertension1 | 30 (32.3) | 54 (58.1) | NS | 11 (15.9) | 49 (71.0) | NS | 42 (45.2) | 44 (47.3) | NS | NS |

| Left kidney size, cm1 | 11.4±1.2 | 11.3±1.1 | NS | 10.4±0.8 | 11.2±1.3 | NS | 11.2±1.1 | 11.2±1.1 | NS | NS |

| Right kidney size, cm1 | 11.4±1.1 | 11.3±1.0 | NS | 10.3±1.1 | 11.0±1.1 | NS | 11.2±1.1 | 11.0±1.1 | NS | NS |

| Ultrasound kidney abnormality1 | 10 (10.8) | 19 (20.4) | NS | 7 (10.1) | 15 (21.7) | <0.03 | 20 (21.5) | 18 (19.4) | NS | NS |

| Laboratory data | ||||||||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL1* | 10.9±1.7 | 11.9±2.2 | <0.03 | 11.4±1.7 | 12.2±2.3 | NS | 10.8±2.1 | 11.7±1.9 | <0.03 | <0.05 |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L1 | 236.7±103.4 | 145.9±89.9 | <0.05 | 260.6±113.7 | 154.2±107.5 | <0.03 | 257.2±154.8 | 156.4±96.9 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L2 | 644.1±204.6 | 179.7±88.2 | <0.05 | 683.3±195.3 | 140.5±65.7 | <0.05 | 625.3±213.9 | 178.0±88.7 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| eGFR1 | 31.2±17.6 | 58.5±37.7 | <0.05 | 28.0±18.1 | 59.1±37.4 | <0.01 | 31.3±21.5 | 54.0±33.4 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| eGFR2 | 8.5±2.6 | 43.9±28.9 | <0.05 | 7.9±2.7 | 55.3±28.5 | <0.05 | 8.6±2.9 | 44.8±28.6 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

| Serum albumin, g/L1 | 28.3±6.7 | 30.1±7.7 | NS | 31.6±7.5 | 32.5±9.8 | NS | 29.3±6.4 | 33.5±7.0 | <0.05 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L1 | 6.4±2.2 | 6.2±2.5 | NS | 4.9±1.8 | 5.3±1.8 | NS | 5.7±1.2 | 5.0±1.4 | <0.02 | NS |

| Cholesterol LDL, mmol/L1 | 4.0±1.6 | 3.9±2.2 | NS | 3.0±1.3 | 3.2±1.5 | NS | 3.7±1.1 | 2.8±1.0 | <0.05 | NS |

| Hemoglobin A1c, %1 | 7.5±1.7 | 7.6±2.0 | NS | 7.0±1.4 | 6.9±1.1 | NS | 7.8±2.0 | 7.4±1.9 | NS | NS |

| Red blood cells1 | 41.3±99.5 | 39.6±81.6 | NS | 195.3±570.0 | 153.6±448.0 | NS | 141.8±455.6 | 87.2±307.2 | NS | NS |

| Presence of RBC count per high power field3, n (%)1 | 31 (33.3) | 41 (44.0) | NS | 9 (13.0) | 40 (58.0) | NS | 31 (33.3) | 27 (29.0) | NS | NS |

| Urinary protein excretion1* | 9.4±6.2 | 8.3±5.4 | NS | 7.1±6.1 | 5.6±5.6 | NS | 9.1±5.2 | 6.6±5.7 | <0.05 | <0.01 |

| Urinary protein excretion2* | 9.8±4.0 | 6.0±6.5 | <0.02 | 5.5±6.4 | 2.6±3.6 | NS | 9.4±5.8 | 3.2±3.6 | <0.05 | <0.05 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or number of patients (%). In 3 of the 255 patients, no follow-up data were available. DN, diabetic nephropathy; NDRD, non-diabetic renal diseases; group 1, DN only; group 2, NDRD only; group 3, mixed (DN and NDRD).

Multivariate and Cox regression analysis was performed and gave significant value for hemoglobin.

Values were taken at biopsy.

Values were taken after biopsy.

Presence of RBCs is considered yes when RBCs is >3.

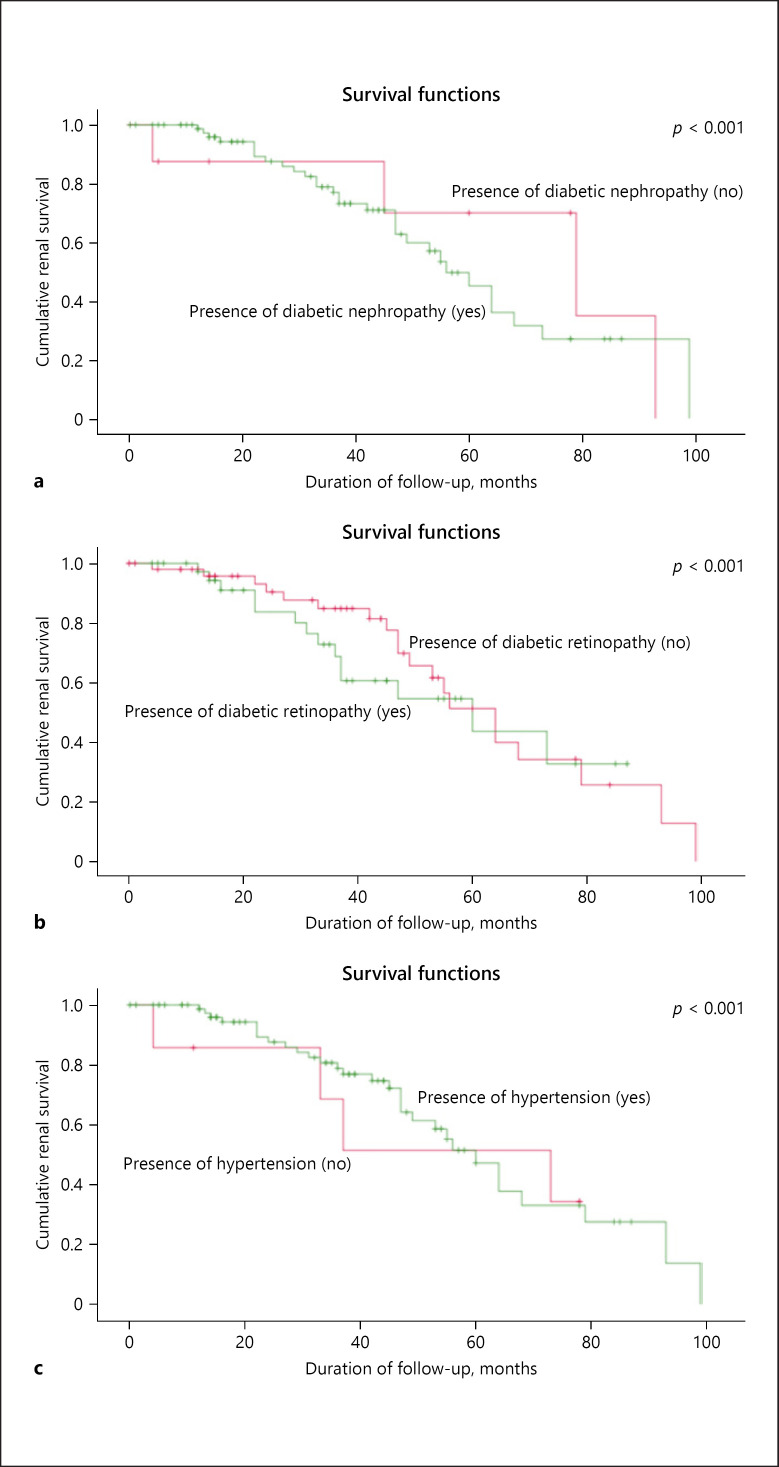

Among the patients in group 1, there were no differences in age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index, duration of diabetes, BP, presence of DN, retinopathy, and kidney sizes between patients with and without ESRD. Laboratory data showed that the non-ESRD patients had higher Hb at biopsy (p < 0.03), lower serum creatinine, and higher eGFR at presentation and on latest follow-up (p < 0.05). Urinary protein excretion at biopsy was greater among the ESRD patients (p < 0.02). The Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis (Fig. 1) shows the presence of DN, diabetic retinopathy, and hypertension was significantly more frequent in the ESRD patients (p < 0.001) compared to the non-ESRD patients.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis of patients in group 1 (diabetic nephropathy alone, DN) with and without diabetic nephropathy (a), diabetic retinopathy (b), and hypertension (c).

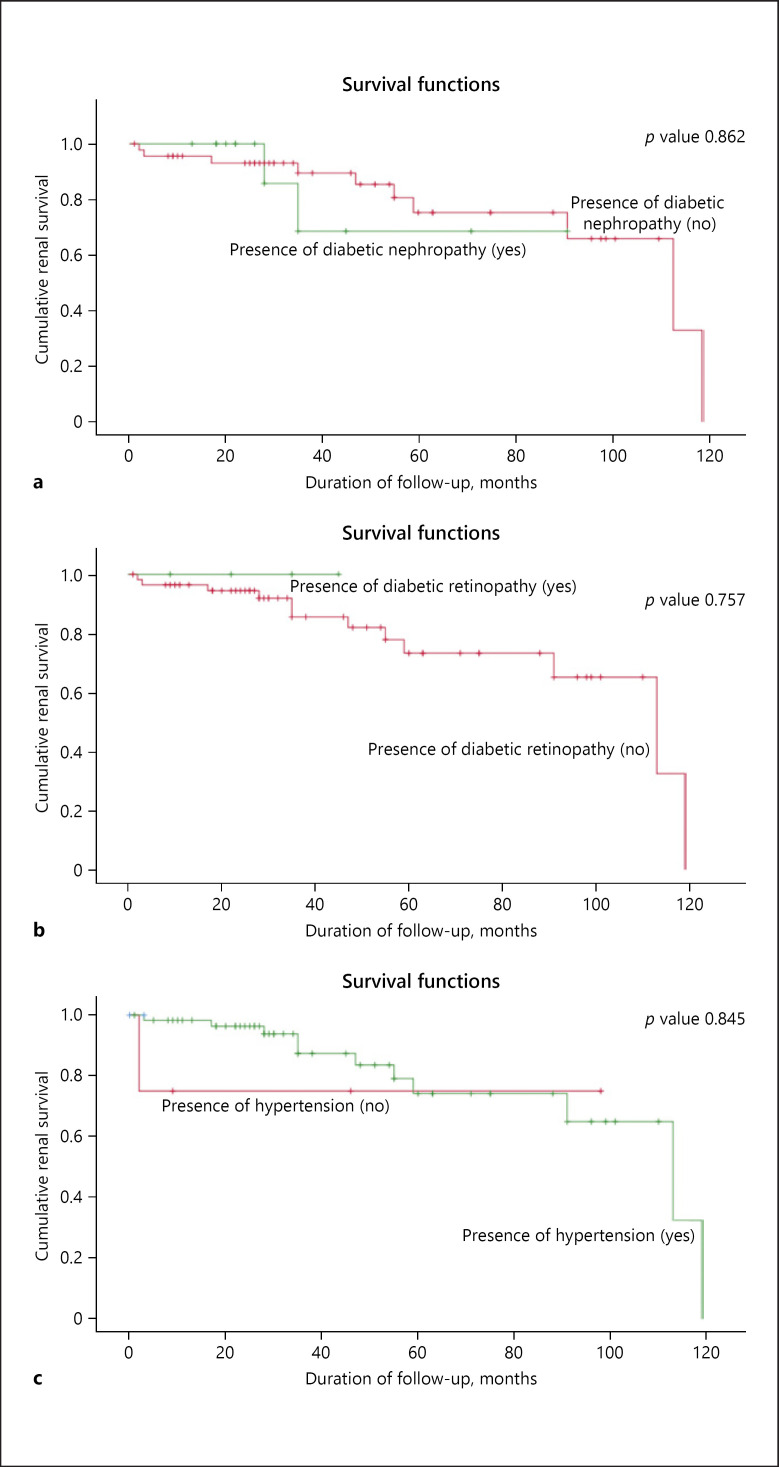

Among patients in group 2, there were no differences in age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index, duration of diabetes, BP, presence of DN, and retinopathy between patients with and without ESRD, but the ultrasound size of the kidneys was significantly more echogenic in the ESRD patients compared to the non-ESRD patients (p < 0.03). Laboratory data showed no difference in Hb between ESRD and non-ESRD patients, but serum creatinine was lower and eGFR higher in the non-ESRD group (p < 0.03) at presentation and on follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis (Fig. 2) shows no significant difference in the presence of DN, retinopathy, and hypertension between ESRD and non-ESRD patients.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis of patients in group 2 (non-diabetic renal disease alone, NDRD) with and without diabetic nephropathy (a), diabetic retinopathy (b), and hypertension (c).

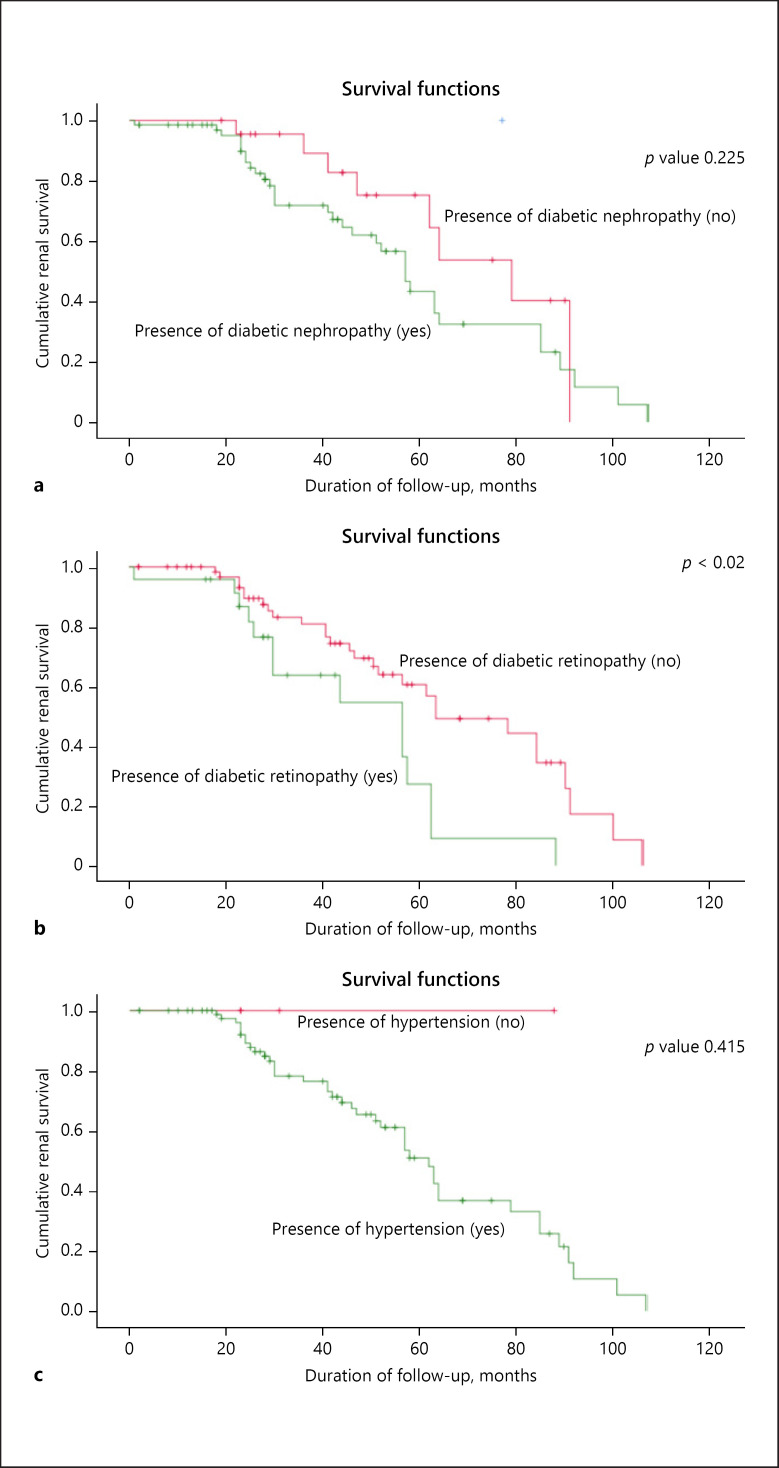

Among the patients in group 3, there were no differences in age, gender, ethnicity, or body mass index between the patients with and without ESRD. The non-ESRD patients had a shorter duration of diabetes (p < 0.04) and lower systolic BP (p < 0.04). Laboratory data showed that non-ESRD patients also had higher Hb at biopsy (p < 0.03), higher serum albumin (p < 0.05), and lower total serum cholesterol (p < 0.02) compared to ESRD patients. Serum creatinine was lower and eGFR higher in the non-ESRD group (p < 0.05) at presentation and on follow-up. Urinary protein excretion at biopsy was greater among ESRD patients (p < 0.05). The Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis (Fig. 3) shows that only presence of retinopathy was significantly different between patients with and without ESRD (p < 0.02), whilst there was no difference in DN or hypertension.

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis of patients in group 3 (mixed group with DN and NDRD) with and without diabetic nephropathy (a), diabetic retinopathy (b), and hypertension (c).

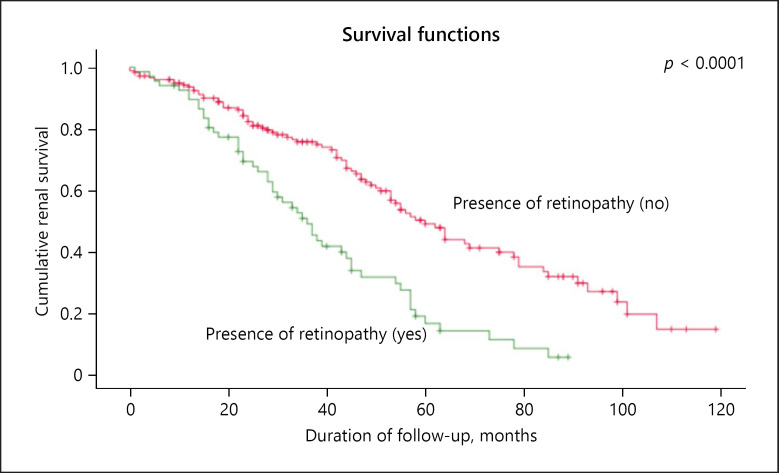

The presence of retinopathy was closely associated with the finding of KW nodules on renal biopsy. Both retinopathy and the KW lesions were associated with decreased Kaplan-Meier survival as shown in Figure 4 for KW nodules, log-rank p < 0.0001.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis of patients with and without the Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodules, where the presence of retinopathy was closely associated with the presence of KW lesions with decreased survival (p < 0.0001).

Summary of Findings in Table 4

Comparing the 3 groups (DN alone, NDRD alone, mixed group) using ANOVA, non-ESRD patients were older (p < 0.04), had lower systolic BP at biopsy (p < 0.03), higher Hb (p < 0.05), higher serum albumin (p < 0.01), and lower urinary protein excretion (p < 0.01) compared to ESRD patients.

Comparing Patients with and without ESRD in the Whole Group

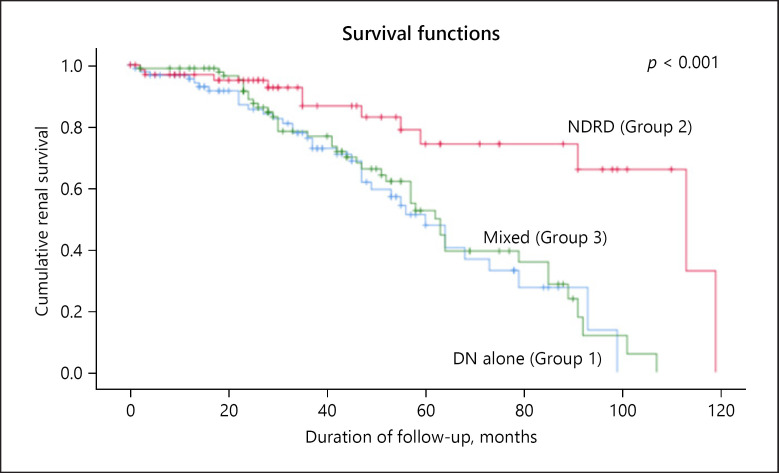

Table 5 compares the patients with and without ESRD (n = 252). Those with non-ESRD were older (p < 0.04), and there were no differences in gender, ethnicity, and body mass index between the patients with and without ESRD. Non-ESRD patients had a shorter duration of follow-up (p < 0.02). Laboratory data showed that non-ESRD patients had lower serum creatinine (p < 0.05) and higher eGFR (p < 0.05) at presentation and on follow-up. The Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis (Fig. 5) shows that patients in group 2 had the longest renal survival (81.2 ± 6.5 months) compared to the other 2 groups: group 1 (51.9 ± 4.1 months) and group 3 (55.4 ± 3.8 months; p < 0.001). This shows that the course of NDRD is milder and could be the result of the patients' therapy for the underlying kidney disease.

Table 5.

Comparison between patients with and without ESRD (n = 252)

| Variable | ESRD (n = 92) | Non-ESRD (n = 160) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years1 | 54±11.8 | 57.3±11.5 | <0.04 |

| Gender male:female, % | 62.0:38.0 | 56.9:43.1 | NS |

| Male gender, n (%) | 57 (62.0) | 91 (56.9) | NS |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Chinese | 72 (78.3) | 122 (76.3) | NS |

| Malay | 17 (18.5) | 22 (13.8) | |

| Indian | 2 (2.2) | 12 (7.5) | |

| Others | 1 (1.1) | 4 (2.5) | |

| Body mass index | 26.8±5.5 | 27.1±4.8 | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg1 | 152.0±27.4 | 143.1±21.7 | <0.03 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg1 | 77.2±12.9 | 73.5±10.8 | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg2 | 143.8±24.2 | 139.8±24.0 | NS |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg2 | 71.6±10.6 | 70.7±11.1 | NS |

| Duration of follow-up, months | 45.7±27.5 | 37.1±25.6 | <0.02 |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 14.6±8.0 | 12.9±8.6 | NS |

| Presence of diabetic nephropathy1 | 67 (72.8) | 98 (61.2) | NS |

| Presence of retinopathy1 | 28 (30.4) | 39 (24.4) | NS |

| Presence of hypertension1 | 83 (90.2) | 147 (91.9) | NS |

| Left kidney size, cm1 | 11.2±1.1 | 11.2±1.2 | NS |

| Right kidney size, cm1 | 11.2±1.1 | 11.1±1.1 | NS |

| Ultrasound kidney abnormality1 | 37 (40.2) | 52 (32.5) | NS |

| Laboratory data | |||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL1 | 10.9±1.9 | 12.0±2.1 | <0.05 |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L1 | 249.6±130.8 | 151.9±97.4 | <0.05 |

| Serum creatinine, µmol/L2 | 640.2±206.6 | 165.9±83.0 | <0.05 |

| eGFR1 | 30.8±19.5 | 57.3±36.2 | <0.05 |

| eGFR2 | 8.5±2.8 | 48.0±29.0 | <0.05 |

| Serum albumin, g/L1 | 29.2±6.7 | 32.0±8.4 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L1 | 5.9±1.8 | 5.5±2.1 | NS |

| Cholesterol LDL, mmol/L1 | 3.7±1.3 | 3.3±1.8 | NS |

| Hemoglobin A1c, %1 | 7.6±1.8 | 7.3±1.7 | NS |

| Red blood cells1 | 108.7±378.2 | 92.7±316.3 | NS |

| Presence of RBCs3, n (%)1 | 71 (77.2) | 108 (67.5) | NS |

| Urinary protein excretion1* | 8.9±5.7 | 6.9±5.6 | <0.01 |

| Urinary protein excretion2* | 9.1±5.3 | 3.9±5.0 | <0.05 |

| Presence of Kimmelstiel-Wilson nodule | 68 (26.9) | 70 (27.8) | <0.00001 |

Values were taken at biopsy.

Values were taken after biopsy.

Presence of RBCs is considered yes when RBCs is >3. Data are presented as mean ± SD or number of patients (%). In 3 of the 255 patients, no follow-up data were available. DN, diabetic nephropathy; NDRD, non-diabetic renal diseases.

Fig. 5.

Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis shows patients with NDRD alone (group 2) had the longest renal survival compared to the other 2 groups, DN alone (group 1) and the mixed group (group 3) (p < 0.001).

Profile of the Diabetic Patients with Non-ESRD

We have determined the characteristics of non-ESRD patients: higher Hb, higher serum albumin, less proteinuria, shorter duration of follow-up, presence of hematuria compared to patients with ESRD in group 1 or group 3, who have lower Hb, longer duration of diabetes, higher systolic BP, higher levels of proteinuria, and more severe renal impairment as in higher serum creatinine and lower eGFR, and lower serum albumin associated with retinopathy. Hence, the presence of retinopathy would suggest that the patient very likely has DN alone or if they have NDRD as well, then they are in the mixed group (DN plus NDRD). The patient with NDRD alone is unlikely to have retinopathy.

Effects of Therapy

Table 6 shows the treatment of the various groups of patients in relation to their outcome in terms of ESRD. For patients in group 1, apart from insulin and oral hypoglycemics, 65.8% were treated with ARB/ACEI, 23% were taking steroids, and 2% were taking immunosuppressants like mycophenolic acid, cyclophosphamide, and cyclosporine; 61% of these patients did not develop ESRD compared to 39% with ESRD (p < 0.01).

Table 6.

Effects of therapy in the 3 groups (n = 252)

| Treatment | Group 1 (n = 93) |

Group 2 (n = 66) |

Group 3 (n = 93) |

p value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESRD | non-ESRD | p value | ESRD | non-ESRD | p value | ESRD | non-ESRD | p value | ||

| Steroids | 7 (7.5) | 14 (15.1) | NS | 8 (11.6) | 21 (30.4) | <0.01 | 15 (16.1) | 14 (15.1) | NS | <0.01 |

| Immunosuppressants | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.1) | NS | 0 (0) | 6 (8.7) | NS | 3 (3.2) | 1 (1.1) | NS | <0.001 |

| Angiotensin receptor blockers | 24 (25.8) | 37 (39.8) | <0.05 | 4 (5.8) | 16 (23.2) | <0.01 | 22 (23.7) | 32 (34.4) | NS | <0.01 |

| No treatment | 4 (4.3) | 5 (5.4) | NS | 0 (0) | 11 (15.9) | NS | 4 (4.3) | 2 (2.2) | NS | <0.05 |

| Total | 36 (38.7) | 57 (61.3) | <0.01 | 12 (18.2) | 54 (81.2) | <0.0001 | 44 (47.3) | 49 (52.7) | NS | <0.02 |

In 3 of the 255 patients, no follow-up data were available. Group 1, DN only; group 2, NDRD only; group 3, mixed (DN and NDRD).

For patients in group 2 (NDRD alone), the majority (42%) had steroids, 8.7% had immunosuppressants, and 29% had ARB/ACEI. 82% of these patients did not have ESRD compared to 18% with ESRD (p < 0.0001).

For group 3 (DN and NDRD, mixed group), 58.1% had ARB/ACEI, 31.2% had steroids and 4.3% had immunosuppressants. 52.7% of these patients did not have ESRD compared to 47% with ESRD. The above data were consistent with the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis which showed that the time interval to ESRD was longest in group 2 compared to group 1 and group 3 as shown in Figure 5 (p < 0.001).

Discussion

Over the past 4 decades we have biopsied an increasing number of patients with diabetes, increasing from 18 to 39% of all secondary GN. The 255 NIDDM patients were biopsied mainly because of suspicion of underlying NDRD associated with DN. In the management of this group of patients, it is imperative that we identify the group with associated NDRD as they are often amenable to therapy. For patients with deteriorating renal function or massive proteinuria due to acute reversible factors, renal biopsy would also be helpful to confirm the underlying renal pathology whether due to worsening renal pathology resulting from diabetes or other acute and treatable reversible elements. In those patients with established DN, we correlated the diabetic lesions with the clinical progression to ESRD to determine the bad prognostic features on renal biopsy in those with DN.

For patients with DN alone, the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis indicates that patients with ESRD had significantly more DN, more KW lesions, and more retinopathy. In contrast to the patients with NDRD alone, there was no significant difference between those with and those without ESRD with respect to the occurrence of hypertension, DN, and retinopathy with regard to renal survival. In clinical practice, it means that a patient with diabetes mellitus with NIDDM with none of the features to suggest associated DN or retinopathy would be unlikely to have DN on renal biopsy and would be more likely to have NDRD alone.

We found that the presence of diabetic retinopathy was the only independent factor associated with ESRD in patients with DN alone as well as those in the mixed group.

The following were predictors for ESRD: high systolic BP at biopsy, longer duration of diabetes, very heavy proteinuria (>6 g/day), and presence of retinopathy.

As for predictors of non-ESRD: the likely factors would be Hb >12 g at biopsy, mild as opposed to moderate renal impairment, proteinuria <3 g/day, serum albumin >32 g, normal kidneys on ultrasound, and absence of retinopathy.

In our series, the significance of high systolic BP at presentation, high HbA1c, and low Hb at biopsy were factors associated with ESRD, and these were confirmed by multivariate analysis and Cox regression. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis identified that the length or duration of diabetes as well as the presence of DN with KW lesions and retinopathy were factors determining ESRD. These findings are consistent with those reported by Chang et al. [11] which showed that higher serum creatinine, higher systolic BP on presentation, and longer duration of diabetes were risk factors for ESRD. The presence of diabetic retinopathy was also identified as an independent determinant for ESRD.

In addition, our data showed that patients with a shorter duration of diabetes and lower serum creatinine levels, with no hypertension and no diabetic retinopathy had better cumulative renal survival.

Liang et al. [28] reported that the presence of dysmorphic RBC and RBC casts were strongly indicative of NDRD [28]. In our study, high urinary dysmorphic RBC count was present in the NDRD group but not in the diabetic group. These findings were consistent with present studies indicating the association of dysmorphic urinary RBCs with the presence of NDRD in NIDDM patients [3, 11, 28].

Our finding of a high Hb among NDRD patients is consistent with that reported by Chang et al. [11] and Fiorentino et al. [3]. A high Hb is considered as an independent predictor of NDRD presence. This was associated with a higher serum albumin and lower serum creatinine and higher eGFR compared to patients with biopsy-proven DN. A low Hb is associated with DN as diabetics have defective oxygen biology associated with low Hb as reported by Thomas et al. [29].

The Kaplan-Meier renal survival analysis shows that the NDRD alone group had better survival compared to the DN alone and the mixed group. The NDRD group has less ESRD and they do not have diabetic retinopathy. Comparing those with and those without diabetic retinopathy we also showed that patients with diabetic retinopathy had poorer survival compared to those who do not have retinopathy, and in agreement with Chang et al. [11] our data showed that retinopathy along with systolic hypertension, higher serum creatinine, and lower Hb was a significant predictor of ESRD.

Chang et al. [11] reported in their series that 34 NIDDM patients with NDRD (44.7%) were treated with immunosuppressants, mostly prednisolone, and 23 out of 34 patients (67.6%) had recovery of renal function. Our data show that 82% of NDRD patients who received treatment did not develop ESRD, and 18% had ESRD. In those with DN alone, 61% did not have ESRD compared to 36% who did. The NDRD patients had longer time to ESRD compared to the DN patients.

In a recent pooled meta-analysis of 48 studies by Fiorentino et al. [3], comprising 4,876 patients, the prevalence of DN, NDRD, and mixed forms ranged from 6.5 to 94%, 3 to 82.9%, and 4 to 45.5%, respectively. Meta-regression identified systolic BP, HbA1c, diabetes duration, and retinopathy as factors inversely correlated with NDRD diagnosis. Our data which showed that systolic BP, high HbA1c, longer duration of diabetes, and presence of diabetic retinopathy were also factors predisposing to ESRD are in agreement with the results of the meta-analyses by Fiorentino et al. [3].

Comparing our NDRD group with the DN group and the mixed group, we showed that the NDRD group had lower serum creatinine and higher eGFR and lower urinary proteinuria and higher serum albumin at presentation and on follow-up. The NDRD group had better glycemic control, lower HbA1c, dysmorphic urinary RBCs, and a better lipid profile at biopsy. Hence, it has been our policy to identify this group of NDRD patients among the NIDDM patients through a renal biopsy in order to diagnose the underlying GN and give them treatment because if untreated, they run the risk of developing ESRD. Our data on treatment of NDRD showed that patients with NDRD had better renal survival. The fact that we and others [3, 11] have done so would explain why this group of patients have better renal survival as they had the appropriate therapy following the histological diagnosis available from the renal biopsy. In our study, 63.5% of our NIDDM patients had associated NDRD. Such a high occurrence is consistent with other reported series [3, 11]. It is important therefore that the etiology of the NDRD is correctly determined for the appropriate therapy to be beneficial. In our series, the common NDRD was FSGS, IgA nephritis, and membranous GN.

To address the issue of the importance of doing renal biopsy to diagnose the type of histological diabetic lesion in a patient with NIDDM, our study shows that the majority of the patients with DN had KW nodules (75%), whilst mesangial expansion occurred in 15% and basement membrane thickening in 8%. KW nodules are considered the most severe lesions with worse prognosis for ESRD [3] whilst mesangial expansion and basement membrane thickening are considered milder lesions with a better prognosis in terms of ESRD [3]. Comparing these lesions, we found that KW lesions were common in the DN alone group and mesangial expansion common in the mixed group. Our studies confirmed that KW lesions are indeed associated with a poorer prognosis leading to a higher occurrence of ESRD among patients with DN as shown in the cumulative renal survival for KW nodules. In a separate study, Zhuo et al. [14] also exploring clinical predictors of the presence of DN or NDRD, reported that a longer duration of diabetes, higher systolic BP, higher HbA1c, and presence of diabetic retinopathy were clinical signs highly predictive of classic KW lesions of DN. These findings support our findings and those of others [3]. Tone et al. [30] also confirmed that diabetic retinopathy was associated with the classic nodular sclerosis of DN, and patients with both DN and retinopathy showed a more severe renal histology than those without retinal damage [31].

The next consideration is whether we should biopsy all NIDDM patients with urinary abnormalities. Should we perhaps consider renal biopsy for all diabetics with urinary abnormalities as it benefits NIDDM patients? For those patients with NIDDM found to have DN alone, a biopsy would be useful to determine the prognosis of NIDDM with lesions of DN. For those found to have NDRD alone, a biopsy would be useful to diagnose and treat NDRD. For those in the mixed group, if they have no retinopathy, they likely have NDRD alone which is treatable. So, for any patient with proteinuria or hematuria, should we not consider renal biopsy to diagnose NDRD and stage DN?

For those NIDDM patients with atypical course or where there is suspicion of associated NDRD, there is a high incidence of 50% to even 80% of successful diagnosis of associated NDRD, and renal biopsy would have great value and be justified based on current indications like our own departmental policy [1, 3]. But, would it be justified to perform routine renal biopsy on all NIDDM patients based on routine indications for CKD patients like proteinuria >1 g/day?

Olsen and Mogensen [32] concluded from an analysis of renal biopsies and the literature and from their own series that if we were to biopsy NIDDM patients based on research indications and not clinical or atypical reasons, the presence of NDRD would be uncommon. They found only 4 patients from their cohort of 33 patients with NIDDM biopsied for research indications. They concluded that there was a bias towards including NDRD in NIDDM and that a renal biopsy should not be routinely performed in NIDDM patients with proteinuria. Caramori's [1] conclusion was that kidney biopsies are a valuable research tool and ought to be considered for diagnostic purposes in patients with atypical clinical presentation [1], implying that we should not do renal biopsies in NIDDM patients unless there is a clinical indication.

Based on the present evidence, for NIDDM patients with an atypical clinical course and suspicion of associated NDRD, we should consider renal biopsy in order to diagnose and treat the underlying NDRD, but for the rest of the NIDDM patients with proteinuria, the verdict is not to offer them routine renal biopsy unless it is for a research indication.

Conclusion

Renal biopsy is of value in indicating the prognosis of the NIDDM patient with DN based on the biopsy findings, depending on whether the patient has mild or severe lesions like KW nodule, which has a poorer prognosis than cases of mere thickening of basement membrane or mesangial expansion. Comparing patients with NDRD versus DN on renal biopsy, those with NDRD would have a better prognosis as their lesions are more amenable to therapy [33]. In fact, Oh et al. [16] found that ESRD occurred in 44% of DN alone patients, 12.3% of NDRD alone patients, and 18.2% of mixed group patients. In our series, ESRD occurred in 39% of DN alone, 18% of NDRD alone, and 45% in the mixed group. Diabetics with frank DN usually have a worse prognosis compared to those with NDRD [11, 34].

But has the time come for us to offer renal biopsy to all NIDDM patients and consider them as any CKD or GN, that is, should those with urinary protein >1 g be biopsied? Most nephrologists would consider renal biopsy for an NIDDM patient based on clinical indications like an atypical clinical course and suspicion of an associated NDRD, but they would not perform a routine renal biopsy as in the case of a CKD patient, unless it is for a research indication.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the local Institutional Review Board committee on human research and conforms to institutional standards (CIRB Ref. No. 3147 E). Waiver of patient consent was approved for this retrospective medical records review.

Disclosure Statement

We declare that there are no conflicts of interest pertaining to this work and we have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Author Contributions

K.T.W. is the lead as well as corresponding author who gathered the data and wrote the manuscript. C.M.C., H.L.C., H.K.T., K.S.W., G.S.L.L., and E.L.: read and corrected the manuscript. C.L. and J.C.: read and wrote part of the manuscript. Y.M.C.: read and prepared the tables. E.W.L.T.: read and prepared figures and references and assisted in submission of manuscript. I.M., J.L.K., C.S.T., and H.Z.T.: read and corrected part of the manuscript. A.H.L.L. and P.H.T. read the renal biopsies. M.F.: head of department who read, corrected and vetted the paper.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Ms Connie Lew for secretarial and administrative assistance.

References

- 1.Caramori ML. Should all patients with diabetes have a kidney biopsy? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017 Jan;32((1)):3–5. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez Suarez ML, Thomas DB, Barisoni L, Fornoni A. Diabetic nephropathy: is it time yet for routine kidney biopsy? World J Diabetes. 2013 Dec;4((6)):245–55. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v4.i6.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiorentino M, Bolignano D, Tesar V, Pisano A, Biesen WV, Tripepi G, et al. ERA-EDTA Immunonephrology Working Group Renal biopsy in patients with diabetes: a pooled meta-analysis of 48 studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017 Jan;32((1)):97–110. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singapore Renal Registry Annual Report. 2016.

- 5.23rd Report of the Malaysian Dialysis and Transplant Registry. 2015.

- 6.Chiu HF, Chen HC, Lu KC, Shu KH, Taiwan Society of Nephrology Distribution of glomerular diseases in Taiwan: preliminary report of National Renal Biopsy Registry-publication on behalf of Taiwan Society of Nephrology. BMC Nephrol. 2018 Jan;19((1)):6. doi: 10.1186/s12882-017-0810-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hwang SJ, Tsai JC, Chen HC. Epidemiology, impact and preventive care of chronic kidney disease in Taiwan. Nephrology (Carlton) 2010 Jun;15(Suppl 2):3–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2010.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jha V. Current status of end-stage renal disease care in India and Pakistan. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3((2)):157–60. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jegatheesan D, Nath K, Reyaldeen R, Sivasuthan G, John GT, Francis L, et al. Epidemiology of biopsy-proven glomerulonephritis in Queensland adults. Nephrology (Carlton) 2016 Jan;21((1)):28–34. doi: 10.1111/nep.12559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Australian Bureau of Statistics . Australian Health Survey: Biomedical Results for Chronic Diseases. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang TI, Park JT, Kim JK, Kim SJ, Oh HJ, Yoo DE, et al. Renal outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without coexisting non-diabetic renal disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011 May;92((2)):198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yassir Z, Benyahia M, Ibrahim D, Kassouati J, Maoujoud O, El Guendouz F, et al. Non-diabetic renal disease in type II diabetes mellitus patients in Mohammed V military hospital, Rabat, Morocco. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2012;6:620–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma SG, Bomback AS, Radhakrishnan J, Herlitz LC, Stokes MB, Markowitz GS, et al. The modern spectrum of renal biopsy findings in patients with diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013 Oct;8((10)):1718–24. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02510213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhuo L, Ren W, Li W, Zou G, Lu J. Evaluation of renal biopsies in type 2 diabetic patients with kidney disease: a clinicopathological study of 216 cases. Int Urol Nephrol. 2013 Feb;45((1)):173–9. doi: 10.1007/s11255-012-0164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaqub S, Kashif W, Hussain SA. Non-diabetic renal disease in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2012 Sep;23((5)):1000–7. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.100882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oh SW, Kim S, Na KY, Chae DW, Kim S, Jin DC, et al. Clinical implications of pathologic diagnosis and classification for diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012 Sep;97((3)):418–24. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chong YB, Keng TC, Tan LP, Ng KP, Kong WY, Wong CM, et al. Clinical predictors of non-diabetic renal disease and role of renal biopsy in diabetic patients with renal involvement: a single centre review. Ren Fail. 2012;34((3)):323–8. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2011.647302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haider DG, Peric S, Friedl A, Fuhrmann V, Wolzt M, Hörl WH, et al. Kidney biopsy in patients with diabetes mellitus. Clin Nephrol. 2011 Sep;76((3)):180–5. doi: 10.5414/cn106955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biesenbach G, Bodlaj G, Pieringer H, Sedlak M. Clinical versus histological diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy—is renal biopsy required in type 2 diabetic patients with renal disease? QJM. 2011 Sep;104((9)):771–4. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bi H, Chen N, Ling G, Yuan S, Huang G, Liu R. Nondiabetic renal disease in type 2 diabetic patients: a review of our experience in 220 cases. Ren Fail. 2011;33((1)):26–30. doi: 10.3109/0886022X.2010.536292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mou S, Wang Q, Liu J, Che X, Zhang M, Cao L, et al. Prevalence of non-diabetic renal disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010 Mar;87((3)):354–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin YL, Peng SJ, Ferng SH, Tzen CY, Yang CS. Clinical indicators which necessitate renal biopsy in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with renal disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2009 Aug;63((8)):1167–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashim Al-Saedi AJ. Pathology of nondiabetic glomerular disease among adult Iraqi patients from a single center. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2009 Sep;20((5)):858–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruggenenti P, Gambara V, Perna A, Bertani T, Remuzzi G. The nephropathy of non-insulin-dependent diabetes: predictors of outcome relative to diverse patterns of renal injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998 Dec;9((12)):2336–43. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9122336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998 Jul;15((7)):539–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus Report of the expert committee on the diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003 Jan;26(Suppl 1):S5–20. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.2007.s5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tervaert TW, Mooyaart AL, Amann K, Cohen AH, Cook HT, Drachenberg CB, et al. Renal Pathology Society Pathologic classification of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010 Apr;21((4)):556–63. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010010010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang S, Zhang XG, Cai GY, Zhu HY, Zhou JH, Wu J, et al. Identifying parameters to distinguish non-diabetic renal diseases from diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013 May;8((5)):e64184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas MC, Tsalamandris C, MacIsaac RJ, Jerums G. The epidemiology of hemoglobin levels in patients with type 2 diabetes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006 Oct;48((4)):537–45. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tone A, Shikata K, Matsuda M, Usui H, Okada S, Ogawa D, et al. Clinical features of non-diabetic renal diseases in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005 Sep;69((3)):237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harada K, Akai Y, Sumida K, Yoshikawa M, Takahashi H, Yamaguchi Y, et al. Significance of renal biopsy in patients with presumed diabetic nephropathy. J Diabetes Investig. 2013 Jan;4((1)):88–93. doi: 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2012.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsen S, Mogensen CE. How often is NIDDM complicated with non-diabetic renal disease? An analysis of renal biopsies and the literature. Diabetologia. 1996 Dec;39((12)):1638–45. doi: 10.1007/s001250050628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.An Y, Xu F, Le W, Ge Y, Zhou M, Chen H, et al. Renal histologic changes and the outcome in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015 Feb;30((2)):257–66. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong TY, Choi PC, Szeto CC, To KF, Tang NL, Chan AW, et al. Renal outcome in type 2 diabetic patients with or without coexisting nondiabetic nephropathies. Diabetes Care. 2002 May;25((5)):900–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]