Abstract

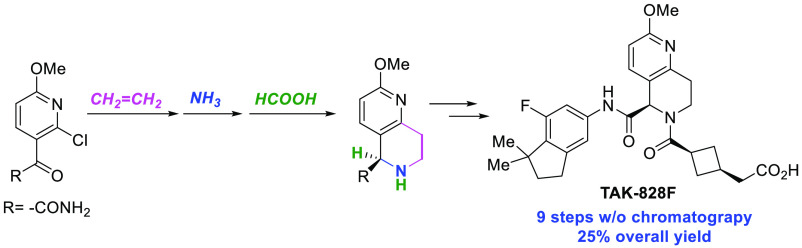

An asymmetric synthesis of the tetrahydronaphthyridine scaffold of TAK-828F as a RORγt inverse agonist has been developed. The synthesis features a newly discovered atom-economical protocol for Heck-type vinylation of chloropyridine using ethylene gas, an unprecedented formation of dihydronaphthyridine directly from 2-vinyl-3-acylpyridine mediated by ammonia, and a ruthenium-catalyzed enantioselective transfer hydrogenation as key steps. This represents the first example of the enantioselective synthesis of a 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-1,6-naphthyridine compound. The new synthesis is also free of chromatography or distillation purification processes and therefore qualifies for extension to large-scale manufacture.

Introduction

Retinoid-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt), which is an orphan nuclear receptor, plays an important role in the differentiation of Th17 cells and production of IL-17A/IL-17F.1 Th17 cells and inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-17A and IL-17F) result in a severe etiology accompanying the enhancement of a systemic new immune response in various autoimmune diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and psoriasis.2 RORγt has been reported to be mainly expressed in Th17 cells and functions as a transcription factor of IL-17A and IL-17F and a master regulator of Th17 cell differentiation.3 Therefore, a medicament that inhibits the action of RORγt is expected to have a treatment effect on various immune diseases by suppressing the differentiation and activation of Th17 cells.

Through drug discovery, TAK-828F (1) has been identified by Takeda as a potent, selective, and orally available RORγt inverse agonist.4 TAK-828F (1) is a tetrahydronaphthyridine ring-fused chiral amino acid bearing indane and cyclobutane moieties through two peptide bonds. The original synthetic route developed by the medicinal chemistry group is shown in Scheme 1.4c Pyridinylethylamine 5 was prepared from 2-methoxy-6-methylpyridine (2) via metalation and nucleophilic addition to paraformaldehyde, amination under Mitsunobu conditions, and finally deprotection using hydrazine. The Pictet–Spengler reaction with an ethyl glyoxylate polymer gave tetrahydronaphthyridine 6 as the HCl salt. After Boc protection of the secondary amine, silver-mediated O-selective methylation and hydrolysis of the ethyl ester afforded carboxylic acid 9, which was then condensed with aminoindane 10. The resulting racemate of 11 was subjected to chiral HPLC resolution to give optically pure (R)-11. After deprotection of the Boc group, the second amide bond formation with cyclobutanecarboxylic acid 13 and deprotection of the tert-butyl ester finally produced target compound 1.

Scheme 1. Original Medicinal Chemistry Synthesis of TAK-828F (1).

As the program advanced into the drug development stage, a synthetic process suitable for producing large quantities of the TAK-828F drug substance was needed. In this regard, the original synthesis described above had inherent issues, including (i) a poor overall yield (3.6% over 12 steps in the longest linear sequence); (ii) chromatographic purification; (iii) cryogenic reaction conditions; (iv) hazardous reagents, such as 1,1′-(azodicarbonyl)dipiperidine (ADDP) and hydrazine; (v) undesired methyl ether cleavage during the Pictet–Spengler reaction, resulting in the need for subsequent re-methylation using a stoichiometric amount of silver carbonate; and (vi) racemic synthesis with chiral HPLC resolution at a late stage of the synthesis. Based on these issues, an alternative synthetic route clearly needed to be pursued to develop a scalable synthetic process. However, after an extensive literature search, the synthesis of tetrahydro-1,6-naphthyridines was found to still be underdeveloped despite their significant value as a scaffold of biologically active molecules.4h,5 Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, no enantioselective synthesis of this particular ring system had been reported at that time, with only two other reports found on non-enantioselective methods.6,7 In the original medicinal chemistry synthesis (Scheme 1), the chiral center of target molecule 1 was generated by a Pictet–Spengler-type cyclization. However, enantioselective Pictet–Spengler reactions have been reported only for highly activated (hetero)aromatic substrates, such as pyrroles or indoles,8 with no successful examples reported for inactivated aromatic rings, such as pyridines. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate a different chemical transformation to establish the chiral stereogenic center in an enantioselective fashion. Scheme 2 outlines the retrosynthetic analysis of the projected synthesis. We envisaged that the chiral stereogenic center in the naphthyridine core could be established by asymmetric reduction of dihydronaphthyridine 17. The resulting chiral tetrahydronaphthyridine 16 could then be coupled with 15 to give 12, which is the same precursor in the existing route to target compound 1 (Scheme 1). We expected that the synthesis of 17 would be achieved by the amination of 2-vinyl-3-acylpyridine 19 followed by intramolecular condensation, inspired by few literature precedents.9−11 For an even more streamlined synthesis, we decided to pursue a tandem reaction to achieve these two transformations in one pot.

Scheme 2. Retrosynthetic Analysis for a New Asymmetric Synthesis of 1.

Results and Discussion

Pyridinyl-2-oxoacetamide 23, a precursor to vinylpyridine key intermediate 19, was prepared via two different synthetic routes (Scheme 3). In route A, the cyanation12 of nicotinic acid chloride 21, followed by bromide-mediated hydration,13 afforded 23 in good yield. In route B, an ethyl oxalyl group was introduced by metalation of 24 with a Grignard reagent, followed by mild-temperature treatment with diethyl oxalate. The resulting 25 was then treated with ammonia in ethanol to give 23 in high yield. As compounds 21 and 22 were susceptible to hydrolysis, route B was eventually selected for scale-up synthesis.

Scheme 3. Synthesis of Pyridinyloxoacetamide 23.

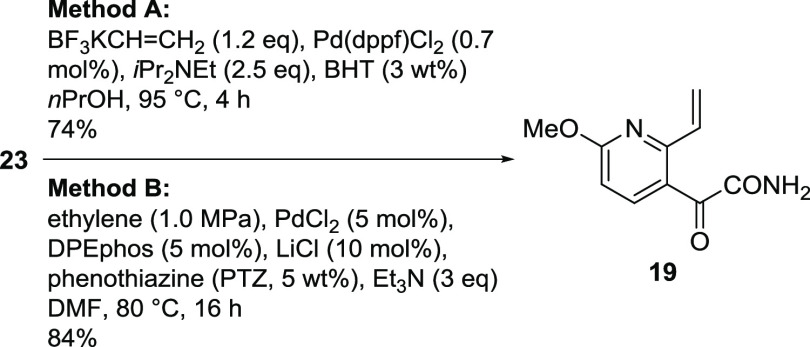

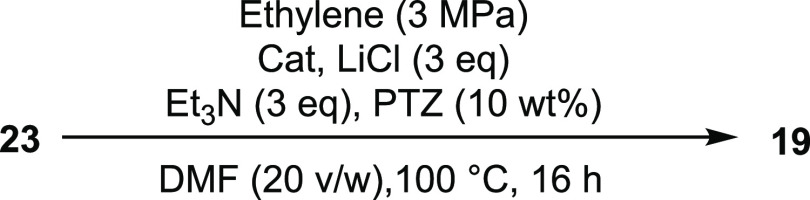

The vinylation of chloropyridine 23 was initially conducted using potassium vinyltrifluoroborate (Scheme 4, method A)10 to give 19 in good yield. As the trifluoroborate was glass-corrosive, not atom-economical, and an expensive vinyl source, its replacement with ethylene gas was attempted. Although the Heck reactions using ethylene gas had been reported for an aryl chloride14 and aryl bromides,15 no example was available for the conversion of chloropyridines. Nonetheless, we launched high-throughput screening (Table 1)16 and successfully identified a new and effective set of conditions for the vinylation of 23 using DPEphos as the ligand (Scheme 4, method B).

Scheme 4. Vinylation of Chloropyridine 23.

Table 1. Summary of High-Throughput Ligand Screening for the Vinylation of 23 with Ethylene Gas.

| HPLC (area %) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | cat (mol %) | 23 | 19 |

| 1 | PdCl2 (20), (p-Tol)3P (40) | 20.2 | 53.6 |

| 2 | PdCl2 (20), (o-MeOC6H4)3P (40) | 43.6 | 9.2 |

| 3 | Pd(OAc)2 (20), Xantphos (20)a | 12.3 | 70.7 |

| 4 | Pd(dppf)Cl2·CH2Cl2 (10) | 69.6 | 13.8 |

| 5 | PdCl2 (20), DPEphos (20) | 0.9 | 61.1 |

| 6 | Scheme 4, method B | NDb | 94.5 |

The reaction was conducted in DMF (50 v/w) in the absence of PTZ.

ND = not detected.

With 2-vinyl-3-acylpyridine 19 in hand, the next target was to develop a one-pot hydroamination/cyclization reaction to construct the dihydronaphthyridine ring (Scheme 5). As projected in the retrosynthesis, dihydronaphthyridine 17 was obtained in good yield by heating 19 in NH3 solution in MeOH. A small amount of aromatized byproduct 26 was also observed, which was presumably generated from the oxidation of 17 by residual oxygen in the reaction mixture. Indeed, when previously isolated 17 was treated with aq. NaOH in MeOH under air, it was immediately oxidized and converted to 26. Owing to the air sensitivity of the product in solution, the formation of 26 in this step was difficult to completely prevent on a lab scale. However, the oxidized impurity was easily removed by an aqueous workup in the next step and caused no significant issue for the overall synthesis.

Scheme 5. Ammonia-Mediated One-Pot Hydroamination/Cyclization.

Determined by 1H NMR.

With the successful development of the ring-closure reaction, our attention was turned to enantioselective reduction of the resulting carbon–nitrogen double bond. High-throughput screening was conducted under more than 100 sets of conditions, including Ru-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation reactions and Ru, Rh, and Ir-catalyzed hydrogenation reactions (Table 2),16 based on previous reports on the asymmetric reduction of dihydroisoquinolines.17,18 As a result, transfer hydrogenation using catalyst 30(19) was found to be optimal (entry 4, Table 2). The reaction was further optimized to afford 16 with excellent conversion and high enantioselectivity (Scheme 6). Compound 16 was then Boc-protected and isolated as compound 31 by crystallization with effective upgrade of the enantiomeric purity.

Table 2. Summary of High-Throughput Catalyst Screening for the Asymmetric Reduction of 17.

| entry | reductant | cat | conditions | HPLC area % | % ee |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H2 (3 MPa) | 27 | tBuOK (10 equiv), MeOH, 40 °C | 25.9 | 100 |

| 2 | H2 (3 MPa) | 28 | nBu4NI (10 equiv), AcOH/toluene 40 °C | 93.5 | 34.2 |

| 3 | H2 (3 MPa) | 29 | MeOH/THF, 40 °C | 82.3 | 85.5 |

| 4 | HCOOH (6 equiv) | 30 | Et3N (2.4 equiv), DMF, rt | 89.1 | 82.7 |

Scheme 6. Ru-Catalyzed Enantioselective Transfer Hydrogenation and Product Isolation.

Determined by HPLC.

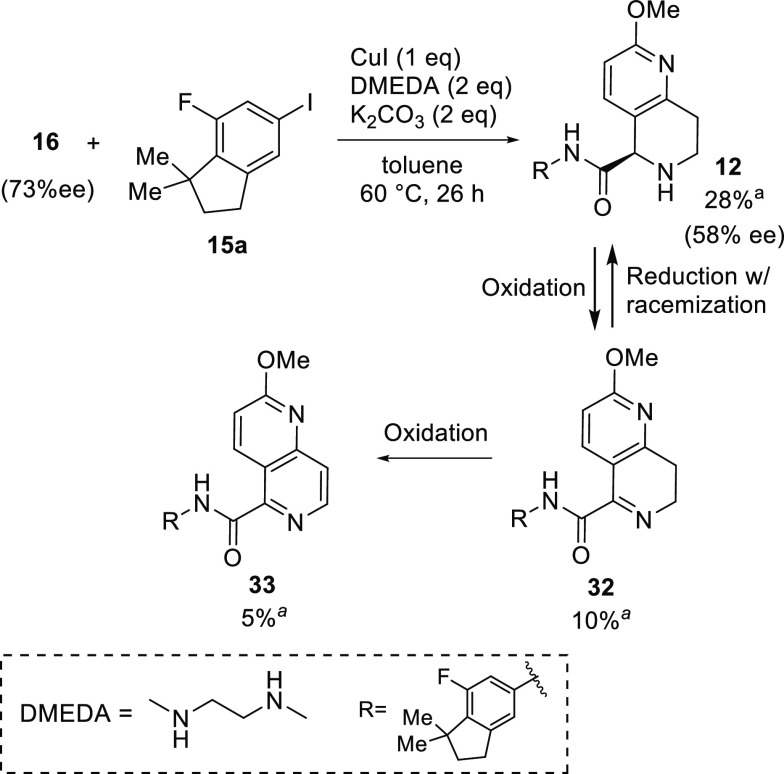

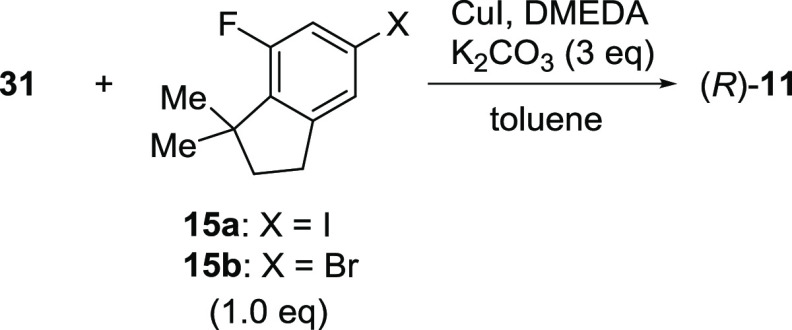

The coupling reaction of 16 or 31 with haloindane 15 was then examined to obtain the corresponding amide 12 or 11 (Scheme 7) as the precursor to target compound TAK-828F (1). Initially, common Pd-catalyzed conditions20 and copper-mediated methods21 for amidation were examined using substrate 16. Although the Pd-catalyzed conditions were not effective, the copper-mediated conditions afforded the desired coupling product 12, albeit in a low yield with oxidized byproducts 32 and 33 (Scheme 7). However, for the copper-mediated reactions, significant erosion of the optical purity was observed, even under mildly basic conditions. This was an unexpected result because the stereogenic center had proven to be stable under strongly basic conditions, as shown in Table 2 (entry 1). Therefore, the undesired racemization was hypothesized to occur mainly through a redox-based pathway between 12 and 32, which might be promoted in the presence of copper. To prevent the undesired redox-based side reactions, N-Boc-protected dihydronaphthyridine 31 was employed as the substrate for the reaction with aryl iodide 15a or bromide 15b as coupling partners (Table 3). Although the use of a substoichiometric amount of copper iodide afforded good conversion with a slight loss in enantioselectivity, the reactivity was only moderate (entry 1). In contrast, the reaction using a stoichiometric amount of copper iodide gave a much better yield with reasonable retention of the stereochemical integrity (entry 2). However, further racemization was observed after a prolonged reaction (entry 3). To our delight, deterioration of the enantiomeric purity was effectively suppressed by lowering the reaction temperature and using a slight excess of aryl iodide 15a (entry 4). The reaction with aryl bromide 15b gave a lower conversion, even at higher temperatures, with significant racemization observed (entry 5) (Table 3).

Scheme 7. Copper-Mediated N-Arylation of 16 and the Plausible Redox-Based Racemization Pathway.

HPLC area %.

Table 3. Copper-Mediated N-Arylation of 31(16).

| entry | Ar-X | CuI (equiv) | DMEDA (equiv) | T (°C) | time (h) | HPLC area % (% ee) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 15a | 0.5 | 1.0 | 40 | 48 | 64 (99.2) |

| 2b | 15a | 1.0 | 2.0 | 40 | 7 | 84 (97.4) |

| 3b | 15a | 1.0 | 2.0 | 40 | 24 | 89 (88.7) |

| 4a | 15ac | 1.1 | 2.2 | rt | 30 | 82d (99.9) |

| 5a | 15b | 1.0 | 2.0 | 100 | 7.5 | 33 (44.0) |

Initial optical purity of 31: >99.9% ee.

Initial optical purity of 31: 98.8% ee.

1.1 equiv was used.

Isolated yield: 87%.

Finally, the validity of the new synthetic route was confirmed by converting the resulting compound (R)-11 into the target molecule 1 according to the original route (Scheme 1). Compared with the original synthesis of (R)-11, the new synthetic route had successfully decreased the number of steps in the longest linear sequence from nine to six, drastically improved the overall yield (from approx. 4 to 25%, Scheme 9), and eliminated the need for hazardous or expensive reagents employed in the original synthesis (Scheme 1). Furthermore, the new intermediate, 15a, was readily prepared from the indane fragment 15b through single-step iodination,22 while the original route required three steps for the conversion of fragment 15b to aminoindane 10 (Scheme 8).4a

Scheme 9. Summary of the New Synthetic Route to (R)-11.

Scheme 8. Synthesis of Iodoindane 15a and Comparison with That of the Original Indane Intermediate 10.

Conclusions

A highly efficient asymmetric synthesis of RORγt inverse agonist TAK-828F (1) has been achieved by developing a new synthetic route to the chiral tetrahydronaphthyridine core scaffold. The new synthesis features several key transformations, namely, the Heck reaction of 2-chloropyridine 23 with ethylene gas, the unprecedented one-pot cyclization and amination of 3-acyl-2-vinylpyridine 19, and the enantioselective transfer hydrogenation of dihydronaphthyridine 17. The new synthetic route is also free of chromatographic purification, making it suitable for scale-up.23 We expect this method to be extendable for the synthesis of various other chiral tetrahydronaphthyridine compounds.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Methods

All reactions were conducted under an inert gas atmosphere using commercially available reagents and solvents without further purification unless otherwise noted. All reactions that required heating were heated using an oil bath. NMR chemical shifts were recorded in ppm relative to tetramethylsilane (0 ppm) as s (singlet), bs (broad singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), or m (multiplet).

2-Chloro-6-methoxynicotinoyl Chloride (21)

A 100 mL round-bottom flask was charged with 2-chloro-6-methoxynicotinic acid 20 (6.0 g, 32.0 mmol) and SOCl2 (12 mL). The mixture was heated to 60 °C for 3 h with stirring. Volatiles were removed using a rotary evaporator to give a slightly yellowish white solid (6.6 g). The product was used in the next reaction without further purification owing to moisture sensitivity. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.40 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.79 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.05 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 165.9, 163.4, 150.3, 145.2, 121.2, 109.8, 55.2.

2-Chloro-6-methoxynicotinoyl Cyanide (22)

To a mixture of CuCN (2.9 g, 32.0 mmol) and CH3CN (24 mL) in a 100mL four-neck round-bottom flask was added 21 (6.0 g, 29.1 mmol). The mixture was heated to 70 °C for 30 min with stirring, followed by cooling to rt. The solvent was exchanged with toluene (30 mL) through repeated concentration using a rotary evaporator and toluene addition. Insoluble materials were filtered out through a Celite pad and the filtrate was concentrated to give a white solid (5.8 g). The product was used in the next reaction without further purification owing to moisture sensitivity. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.30 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.86 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.09 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.7, 163.7, 151.8, 144.1, 121.2, 113.0, 110.6, 55.5.

Ethyl 2-(2-Chloro-6-methoxypyridin-3-yl)-2-oxoacetate (25)

A 1 L four-neck round-bottom flask was charged with 24 (120.0 g, 539.4 mmol) and dry THF (240 mL), and the resulting solution was cooled to 12 °C. A THF solution of isopropylmagnesium chloride (269.7 mL, 2 M, 1.2 equiv) was added dropwise over 40 min while keeping the reaction stirred at rt for 2 h. A separate 2 L round-bottom flask was charged with diethyl oxalate (87.6 mL, 1.2 equiv) and dry THF (240 mL) and cooled to −8 °C. The arenemagnesium solution prepared as mentioned above was added dropwise to the diethyl oxalate solution over 75 min while keeping the reaction temperature below 1 °C. The reaction was stirred at 0–3 °C for 1 h and quenched by adding 1 M aq HCl (600 mL). After stirring at rt for 10 min, the organic layer was separated. The solvent was exchanged with EtOH through repeated concentration using a rotary evaporator and EtOH addition. The net solution volume was adjusted to 480 mL by adding EtOH, and the solution was seeded with 25 and stirred at rt for 20 min to give a suspension. H2O (480 mL) was added over 1 h, and the resulting suspension was stirred at rt for 15 h. The solids were collected by filtration, washed with 1:2 EtOH/H2O (450 mL), and dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for 5 h to afford 25 (107.8 g) as a pale purple solid. The purity was determined to be 94.0 wt % by HPLC assay; 77% yield (corrected according to wt % purity). An analytically pure sample was prepared by recrystallization from EtOH. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.07 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.42 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 184.8, 166.1, 163.6, 149.7, 142.6, 122.3, 110.4, 62.8, 55.0, 13.9; HRMS m/z [M + H]+ calcd. for C10H10ClNO4 244.0350, found 244.0371.

2-(2-Chloro-6-methoxypyridin-3-yl)-2-oxoacetamide (23)

(From 22) To a mixture of H2SO4 (51.0 mL), NaBr (523.4 mg, 5.1 mmol), and Ac2O (4.8 mL, 50.9 mmol) in a 200 mL four-neck round-bottom flask was added 22 (10.0 g, 50.9 mmol) at rt. The mixture was stirred at rt for 2 h and then poured into 8 M aq NaOH (144 mL) with crushed ice. The precipitate was filtered and washed with 1 M aq NaOH. 1 M HCl (30 mL) was then added to the mixture to generate a precipitate, which was collected by filtration, washed sequentially with 5% aq NaHCO3 (40 mL) and H2O (20 mL), and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C to give 23 as a colorless solid (8.3 g); 76% yield for three steps from 20.

(From 25) A 2 L four-neck round-bottom flask equipped with a mechanical stirrer was charged with 25 (100.0 g, 94.0 wt %, 385.8 mmol) and 2 M NH3 in EtOH (600 mL). The reaction initially became a homogeneous solution and then turned into a thick slurry after stirring at rt for 5 min. The resulting slurry was stirred at rt for a total of 24 h. The solids were collected by filtration, washed with EtOH (200 mL), and dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for 2 h to give 23 as a colorless solid (77.6 g); 94% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.37 (bs, 1H), 8.13 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (bs, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.96 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 226.3, 202.7, 202.2, 184.7, 181.1, 160.2, 147.1, 92.2; HRMS m/z [M + H]+ calcd. for C8H7ClN2O3 215.0202, found 215.0218.

2-(6-Methoxy-2-vinylpyridin-3-yl)-2-oxoacetamide (19)

Method A (Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling)

A 1 L four-neck round-bottom flask was charged with 23 (30.0 g, 139.8 mmol), potassium trifluorovinylborate (22.5 g, 1.2 equiv), Pd(dppf)Cl2 (0.7 g, 0.7 mol %), BHT (0.9 g), 1-propanol (150 mL), and N,N-diisopropylethylamine (60.9 mL, 2.5 equiv). The flask was evacuated and refilled with nitrogen five times. The resulting mixture was heated to 95 °C for 3.5 h. After cooling to 55 °C and diluting with THF (300 mL), the reaction mixture was stirred at 55 °C for 15 min and filtered to remove the insoluble materials, which were rinsed with warm THF (75 mL). The filtrate and washings were combined and concentrated to 169 g using a rotary evaporator. The residue was diluted with EtOH (150 mL) and concentrated to ∼150 g using a rotary evaporator, which was repeated a total of three times. The resulting slurry was chilled to 5 °C for 1 h with stirring. The solids were collected by filtration, washed with cold EtOH (60 mL), and dried in a vacuum oven at 45 °C for 2 h to afford 19 (22.3 g) as a pale yellow solid. The purity was determined to be 96.2 wt % by HPLC assay; 74% yield (corrected according to wt % purity). An analytically pure sample was prepared by further vacuum drying. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.32 (brs, 1H), 8.03 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (bs, 1H), 7.39 (dd, J = 10.6, 16.7 Hz, 1H), 6.87 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 6.53 (dd, J = 2.2, 16.7 Hz, 1H), 5.65 (dd, J = 2.2, 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.99 (s, 3H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 191.2, 166.5, 164.2, 153. 9, 142.6, 132.9, 122.6, 120.9, 109.6, 53.5; HRMS m/z [M + H]+ calcd. for C10H10N2O3 207.0758, found 207.0764.

Method B (Heck Reaction)

A 120 mL autoclave vessel was charged with 23 (200.0 mg, 0.93 mmol), PdCl2 (8.3 mg, 5.0 mol %), DPEphos (25.0 mg, 5.0 mol %), LiCl (3.9 mg, 10.0 mol %), phenothiazine (10.0 mg), dry DMF (4.0 mL), and triethylamine (390.0 μL, 3.0 equiv). The resulting mixture was stirred at 80 °C under ethylene pressure (1.0 MPa) for 16 h. The reaction was allowed to cool to rt and the resulting mixture was purified by silica gel chromatography (20% EtOAc/hexane) to afford 19 (161.7 mg) as a pale yellow solid; 84% yield. The product was also isolated as crystals from the crude mixture using the same operation as in method A, affording an 80% yield.

2-Methoxy-7,8-dihydro-1,6-naphthyridine-5-carboxamide (17)

A 120 mL autoclave vessel was charged with 19 (2.0 g, 9.7 mmol), BHT (80 mg), and dry MeOH (80 mL). The resulting mixture was stirred at rt under NH3 pressure (0.30 MPa) for 2 h. The vessel was closed and heated to 60 °C (bath temperature) for 6 h. The pressure gauge indicated 0.65 MPa. The reaction was allowed to cool to rt and concentrated to 25 g using a rotary evaporator. The assay yield of the reaction solution was determined to be 79% by HPLC. The mixture was diluted with 2-propanol (20 mL) and concentrated to 25 g, which was repeated a total of four times. The resulting slurry was aged at rt for 1 h. The solids were collected by filtration, washed with 2-propanol (8 mL), and suction-dried at rt for 30 min to give 17 (1.24 g) as an off-white solid. 1H NMR indicated the presence of 26 (∼4 mol %); 60% yield (excluding impurity 26). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.20 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 7.85 (bs, 1H), 7.51 (bs, 1H), 6.75 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.83 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 2.77 (t, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 166.6, 164.3, 158.6, 157.6, 138.1, 115.8, 108.2, 53.5, 46.6, 27.8; HRMS m/z [M + H]+ calcd. for C10H11N3O2 206.0948, found 206.0924.

The use of a commercially available NH3 solution in MeOH instead of NH3 gas gave comparable results.

(R)-tert-Butyl-5-carbamoyl-2-methoxy-7,8-dihydro-1,6-naphthyridine-6-(5H)-carboxylate (31)

A 100 mL four-neck round-bottom flask was charged with 17 (2.0 g, 9.8 mmol), ammonium formate (1.8 g, 29.2 mmol), chloro(p-cymene)[(R,R)-N-(isobutanesulfonyl)-1,2-diphenylethylenediamine]ruthenium(II) (58.7 mg, 0.098 mmol), and CH3CN (50 mL). After stirring at 35 °C for 24 h under continuous N2 flow to remove CO2, 1 M aq citric acid (24 mL) and toluene (12 mL) were added at rt. The organic layer was separated and extracted with 1 M aq citric acid (12 mL) twice. The aqueous layers were combined and washed with toluene (12 mL), followed by the addition of K2CO3 (14.5 g). (Boc)2O (2.34 g, 10.7 mmol) in toluene (2 mL) was then added dropwise at rt, and the resulting mixture was stirred at rt for 1 h. The aqueous layer was separated and extracted with toluene (12 mL) twice, and the combined organic layer was washed with water (6 mL). The solvent was exchanged with MeOH (10 mL) through repeated concentration using a rotary evaporator and MeOH addition. The product was then precipitated by adding water (4 mL), followed by the slow addition of more water (6 mL). After stirring the slurry at 20 °C, the resulting precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with a mixture of MeOH (1.3 mL) and water (2.7 mL), and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C to give 31 (2.16 g) as a white solid; 72% yield, 98.9% ee. Although NMR spectra in CDCl3 showed complex patterns due to the presence of rotamers, the peaks were simplified when using DMSO-d6 as the solvent. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.74–7.84 (m, 1H), 7.71 (bs, 1H), 7.15 (br d, 1H), 6.70 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 5.29 (s, 0.5H), 5.17 (s, 0.5H), 3.82 (s, 3H), 3.73–3.81 (m, 2H), 2.84–2.95 (m, 1H), 2.71–2.82 (m, 1H), 1.43 (br d, 9H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.5, 173.1, 162.5, 154.8, 154.6, 152.8, 152.5, 138.8, 138.6, 121.1, 120.7, 108.8, 80.0, 57.7, 56.7, 53.5, 31.7, 28.5; HRMS m/z [M + H]+ calcd. for C15H21N3O4 308.1578, found 308.1605.

(R)-2-Methoxy-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-1,6-naphthyridine-5-carboxamide (16)

A 30 mL round-bottom flask was charged with 31 (300.0 mg, 0.98 mmol), THF (1.5 mL), and 6 M HCl (1.2 mL). The mixture was stirred at rt for 6 h and basified by adding 4 M aq NaOH (2.4 mL). The aqueous layer was separated and extracted with THF (1.5 mL). The combined organic layer was concentrated using a rotary evaporator to give 16 as a colorless solid (181.0 mg); 89% yield. If necessary, the product could be further purified, including an improved ee, by recrystallization from EtOAc. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.59 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (bs, 1H), 7.19 (bs, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 4.29 (s, 1H), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.03–3.12 (m, 1H), 2.83–2.97 (m, 2H), 2.58–2.75 (m, 2H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 174.8, 162.0, 152.9, 138.7, 123.2, 108.1, 58.6, 53.3, 41.0, 32.6; HRMS m/z [M + H]+ calcd. for C10H13N3O2 208.1062, found 208.1081.

(R)-tert-Butyl-5-((7-fluoro-1,1-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-5-yl)carbamoyl)-2-methoxy-7,8-dihydro-1,6-naphthyridine-6-(5H)-carboxylate ((R)-11)

A 30 mL Schlenk tube was charged with 31 (2.0 g, 6.5 mmol), K2CO3 (2.0 g, 14.1 mmol), CuI (1.4 g, 7.2 mmol), toluene (8.0 mL), 15a (2.2 g, 7.7 mmol), and N,N′-dimethylethylenediamine (1.6 mL, 14.5 mmol). The vessel was evacuated and refilled with argon five times, and the mixture was then stirred at rt for 30 h, followed by the addition of 25% aq NH3 (50 mL) and EtOAc (16 mL). The organic layer was separated, washed with saturated NH4Cl aq (16 mL) repeatedly until the blue color disappeared, and then rinsed with H2O (16 mL). The organic solvent was exchanged with EtOH (2 mL) through repeated concentration using a rotary evaporator and EtOH addition. AcOH (2 mL), H2O (2 mL), and a crystal seed of (R)-11 were added to form a seed bed. After slow addition of H2O (9 mL), the resulting precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with H2O (10 mL), and dried in a vacuum oven at 50 °C to give (R)-11 as a colorless crystalline solid (1.4 g). 91% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.96 (bs, 1H), 7.52 (m, 1H), 7.08 (d, J = 11.6 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 5.62 (bs, 1H), 3.95–4.10 (m, 1H), 3.91 (s, 3H), 3.55 (bs, 1H), 2.87–2.99 (m, 2H), 2.85 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.89 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.53 (s, 9H), 1.33 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.9, 163.1, 160.4, 158.4, 152.2, 146.9, 146.8, 138.8, 137.8, 133.4, 118.8, 111.6, 108.8, 105.8, 105.6, 81.8, 53.5, 44.4, 41.9, 40.5, 31.5, 31.1, 28.4, 27.5; HRMS m/z [M + H]+ calcd. for C26H32FN3O4 470.2434, found 470.2450.

5-Iodo-7-fluoro-1,1-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-indene (15a)

A 30 mL Schlenk tube was charged with CuI (95.2 mg, 0.5 mmol), NaI (3.0 g, 20.0 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (10 mL), N,N′-dimethylethylenediamine (107.5 μL, 1.0 mmol), and 15b (2.4 g, 10.0 mmol). The mixture was stirred overnight under reflux. The reaction was cooled to rt and filtered through a Celite pad. The filter cake was washed with EtOAc (20 mL), and the combined solution was washed successively with 10% aq NH3 (10 mL, twice), 20% aq citric acid (10 mL), and H2O (10 mL). The organic solvent was then removed using a rotary evaporator, and the solution was azeotropically dried with EtOH, affording the target product as a yellow oil (2.7 g); 94% yield. An analytically pure sample was prepared by distillation (106 °C, 5.0 mmHg). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.29 (s, 1H), 7.16 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 2.89 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.34 (s, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.5, 158.5, 148.5 (d, J = 7.3 Hz), 137.6 (d, J = 15.4 Hz), 129.6 (d, J = 3.6 Hz), 122.8 (d, J = 23.6 Hz), 90.6 (d, J = 7.3 Hz), 44.6 (d, J = 1.8 Hz), 41.7, 30.7, 27.3 (d, J = 1.8 Hz); Anal. calcd. for C11H12FI: C, 45.54; H, 4.17; found: C, 45.16; H, 3.96.

Acknowledgments

We thank Keisuke Majima, Tatsuya Ito, Masatoshi Yamada, Masayuki Yamashita, and Sayuri Hirano for discussions and suggestions regarding the chemistry in this study.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.joc.0c01311.

Tables for high-throughput screening results, NMR spectra, and HPLC charts for chiral substrates (PDF)

Author Present Address

† Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited, 26-1 Muraoka-Higashi 2-Chome, Fujisawa, Kanagawa 251-8555, Japan.

Author Present Address

‡ Takeda California, Inc., 9625 Towne Centre Drive, San Diego, California 92121, United States.

Author Present Address

§ SPERA Pharma, Inc., 17-85, Jusohonmachi 2-Chome, Yodogawa-ku, Osaka 532-0024, Japan.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ivanov I. I.; McKenzie B. S.; Zhou L.; Tadokoro C. E.; Lepelley A.; Lafaille J. J.; Cua D. J.; Littman D. R. The Orphan Nuclear Receptor RORγt Directs the Differentiation Program of Proinflammatory IL-17+ T Helper Cells. Cell 2006, 126, 1121–1133. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Nakae S.; Nambu A.; Sudo K.; Iwakura Y. Suppression of Immune Induction of Collagen-Induced Arthritis in IL-17-deficient Mice. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 6173–6177. 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Komiyama Y.; Nakae S.; Matsuki T.; Nambu A.; Ishigame H.; Kakuta S.; Sudo K.; Iwakura Y. IL-17 Plays an Important Role in the Development of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. Immunol. 2006, 177, 566–573. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Huh J. R.; Leung M. W. L.; Huang P.; Ryan D. A.; Krout M. R.; Malapaka R. R. V.; Chow J.; Manel N.; Ciofani M.; Kim S. V.; Cuesta A.; Santori F. R.; Lafaille J. J.; Xu H. E.; Gin D. Y.; Rastinejad F.; Littman D. R. Digoxin and its derivatives suppress TH17 cell differentiation by antagonizing RORγt activity. Nature 2011, 472, 486–490. 10.1038/nature09978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Solt L. A.; Kumar N.; Nuhant P.; Wang Y.; Lauer J. L.; Liu J.; Istrate M. A.; Kamenecka T. M.; Roush W. R.; Vidović D.; Schürer S. C.; Xu J.; Wagoner G.; Drew P. D.; Griffin P. R.; Burris T. P. Suppression of TH17 differentiation and autoimmunity by a synthetic ROR ligand. Nature 2011, 472, 491–494. 10.1038/nature10075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yamamoto S.; Shirai J.; Oda T.; Kono M.; Ochida A.; Imada T.; Tokuhara H.; Tomata Y.; Ishii N.; Tawada M.; Fukase Y.; Yukawa T.; Fukumoto S.. Heterocyclic Compounds and Their Use as Retinoid-Related Orphan Receptor (ROR) Gamma-T Inhibitors. WO Patent WO2016002968, January 07, 2016.; b Shibata A.; Uga K.; Sato T.; Sagara M.; Igaki K.; Nakamura Y.; Ochida A.; Kono M.; Shirai J.; Yamamoto S.; Yamasaki M.; Tsuchimori N. Pharmacological Inhibitory Profile of TAK-828F, a Potent and Selective Orally Available RORγt Inverse Agonist. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 150, 35–45. 10.1016/j.bcp.2018.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kono M.; Ochida A.; Oda T.; Imada T.; Banno Y.; Taya N.; Masada S.; Kawamoto T.; Yonemori K.; Nara Y.; Fukase Y.; Yukawa T.; Tokuhara H.; Skene R.; Sang B.-C.; Hoffman I. D.; Snell G. P.; Uga K.; Shibata A.; Igaki K.; Nakamura Y.; Nakagawa H.; Tsuchimori N.; Yamasaki M.; Shirai J.; Yamamoto S. Discovery of [cis-3-({(5R)-5-[(7-Fluoro-1,1-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-inden-5-yl)carbamoyl]-2-methoxy-7,8-dihydro-1,6-naphthyridin-6(5H)-yl}carbonyl)cyclobutyl]acetic Acid (TAK-828F) as a Potent, Selective, and Orally Available Novel Retinoic Acid Receptor-Related Orphan Receptor γt Inverse Agonist. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 2973–2988. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Nakagawa H.; Koyama R.; Kamada Y.; Ochida A.; Kono M.; Shirai J.; Yamamoto S.; Ambrus-Aikelin G.; Sang B.-C.; Nakayama M. Biochemical Properties of TAK-828F, a Potent and Selective Retinoid-Related Orphan Receptor Gamma T Inverse Agonist. Pharmacology 2018, 102, 244–252. 10.1159/000492226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Igaki K.; Nakamura Y.; Komoike Y.; Uga K.; Shibata A.; Ishimura Y.; Yamasaki M.; Tsukimi Y.; Tsuchimori N. Pharmacological Evaluation of TAK-828F, a Novel Orally Available RORγt Inverse Agonist, on Murine Colitis Model. Inflammation 2019, 42, 91–102. 10.1007/s10753-018-0875-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Igaki K.; Nakamura Y.; Tanaka M.; Mizuno S.; Yoshimatsu Y.; Komoike Y.; Uga K.; Shibata A.; Imaichi H.; Satou T.; Ishimura Y.; Yamasaki M.; Kanai T.; Tsukimi Y.; Tsuchimori N. Pharmacological effects of TAK-828F: an orally available RORγt inverse agonist, in mouse colitis model and human blood cells of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflammation Res. 2019, 68, 493–509. 10.1007/s00011-019-01234-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Nakamura Y.; Igaki K.; Uga K.; Shibata A.; Yamauchi H.; Yamasaki M.; Tsuchimori N. Pharmacological evaluation of TAK-828F, a novel orally available RORγt inverse agonist, on murine chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model. J. Neuroimmunol. 2019, 335, 577016 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2019.577016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Yukawa T.; Nara Y.; Kono M.; Sato A.; Oda T.; Takagi T.; Sato T.; Banno Y.; Taya N.; Imada T.; Shiokawa Z.; Negoro N.; Kawamoto T.; Koyama R.; Uchiyama N.; Skene R.; Hoffman I.; Chen C.-H.; Sang B.-C.; Snell G.; Katsuyama R.; Yamamoto S.; Shirai J. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Retinoic Acid-Related Orphan Receptor γt (RORγt) Agonist Structure-Based Functionality Switching Approach From In House RORγt Inverse Agonist to RORγt Agonist. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1167–1179. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Peese K. M.; Allard C. W.; Connolly T.; Johnson B. L.; Li C.; Patel M.; Sorensen M. E.; Walker M. A.; Meanwell N. A.; McAuliffe B.; Minassian B.; Krystal M.; Parker D. D.; Lewis H. A.; Kish K.; Zhang P.; Nolte R. T.; Simmermacher J.; Jenkins S.; Cianci C.; Naidu B. N. 5,6,7,8-Tetrahydro-1,6-naphthyridine Derivatives as Potent HIV-1-Integrase-Allosteric-Site Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 1348–1361. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li J.; Qin C.; Yu Y.; Fan H.; Fu Y.; Li H.; Wang W. Lewis Acid-Catalyzed C(sp3)-C(sp3) Bond Forming Cyclization Reactions for the Synthesis of Tetrahydroprotoberberine Derivatives. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017, 359, 2191–2195. 10.1002/adsc.201601423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Cruz D.; Wang Z.; Kibbie J.; Modlin R.; Kwon O. Diversity through phosphine catalysis identifies octahydro-1,6-naphthyridin-4-ones as activators of endothelium-driven immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6769–6774. 10.1073/pnas.1015254108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Shiozawa A.; Ichikawa Y.; Komuro C.; Ishikawa M.; Furuta Y.; Kurashige S.; Miyazaki H.; Yamanaka H.; Sakamoto T. Antivertigo Agents. IV. Synthesis and Antivertigo Activity of 6-[ω-(4-Aryl-1-piperazinyl) alkyl]-5, 6, 7, 8-tetrahydro-1, 6-naphthyridines. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1984, 32, 3981–3993. 10.1248/cpb.32.3981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For an Isolation as a Diastereomer, see: Mercer S. P.; Roecker A. J.. Tetrahydronapthyridine Orexin Receptor Antagonists. WO Patent WO2011005636, January 13, 2011.

- For an Optical Resolution by Using Chiral Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) System, see:Horne D. B.; Tamayo N. A.; Bartberger M. D.; Bo Y.; Clarine J.; Davis C. D.; Gore V. K.; Kaller M. R.; Lehto S. G.; Ma V. V.; Nishimura N.; Nguyen T. T.; Tang P.; Wang W.; Youngblood B. D.; Zhang M.; Gavva N. R.; Monenschein H.; Norman M. H. Optimization of Potency and Pharmacokinetic Properties of Tetrahydroisoquinoline Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin 8 (TRPM8) Antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 2989–3004. 10.1021/jm401955h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hansen C. L.; Ohm R. G.; Olsen L. B.; Ascic E.; Tanner D.; Nielsen T. E. Catalytic Enantioselective Synthesis of Tetrahydocarbazoles and Exocyclic Pictet-Spengler-Type Reactions. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 5990–5993. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ruiz-Olalla A.; Würdemann M. A.; Wanner M. J.; Ingemann S.; van Maarseveen J. H.; Hiemstra H. Organocatalytic Enantioselective Pictet-Spengler Approach to Biologically Relevant 1-benzyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline Alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 5125–5132. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mittal N.; Sun D. X.; Seidel D. Conjugate-Base-Stabilized Brønsted Acids: Catalytic Enantioselective Pictet–Spengler Reactions with Unmodified Tryptamine. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 1012–1015. 10.1021/ol403773a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Huang D.; Xu F.; Lin X.; Wang Y. Highly Enantioselective Pictet–Spengler Reaction Catalyzed by SPINOL-Phosphoric Acids. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 3148–3152. 10.1002/chem.201103207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e He Y.; Lin M.; Li Z.; Liang X.; Li G.; Antilla J. C. Direct Synthesis of Chiral 1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazines via a Catalytic Asymmetric Intramolecular Aza-Friedel-Crafts Reaction. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4490–4493. 10.1021/ol2018328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Moyano A.; Rios R. Asymmetric Organocatalytic Cyclization and Cycloaddition Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 4703–4832. 10.1021/cr100348t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Larghi E. L.; Amongero M.; Bracca A. B. J.; Kaufman T. S. The intermolecular Pictet-Spengler condensation with chiral carbonyl derivatives in the stereoselective syntheses of optically-active isoquinoline and indole alkaloids. ARKIVOC 2005, 98–153. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus G.; Levine R. The Pyridylethylation of Active Hydrogen Compounds. V. The Reaction of Ammonia, Certain Amines, Amides and Nitriles with 2- and 4-Vinylpyridine and 2-Methyl-5-vinylpyridine1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1956, 78, 4127–4130. 10.1021/ja01597a073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turlington M.; Malosh C.; Jacobs J.; Manka J. T.; Noetzel M. J.; Vinson P. N.; Jadhav S.; Herman E. J.; Lavreysen H.; Mackie C.; Bartolomé-Nebreda J. M.; Conde-Ceide S.; Martín-Martín M. L.; Tong H. M.; López S.; MacDonald G. J.; Steckler T.; Daniels J. S.; Weaver C. D.; Niswender C. M.; Jones C. K.; Conn P. J.; Lindsley C. W.; Stauffer S. R. Tetrahydronaphthyridine and Dihydronaphthyridinone Ethers as Positive Allosteric Modulators of the Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 5 (mGlu5). J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5620–5637. 10.1021/jm500259z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussenether T.; Troschütz R. Synthesis of 5-phenyl-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-1,6-naphthyridines and 5-phenyl-6,7,8,9-tetrahydro-5H-pyrido[3,2-c]azepines as potential D1 receptor ligands. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2004, 41, 857–865. 10.1002/jhet.5570410602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Veerareddy A.; Surendrareddy G.; Dubey P. K. Total Syntheses of AF-2785 and Gamendazole—Experimental Male Oral Contraceptives. Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 2236–2241. 10.1080/00397911.2012.696306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Goudedranche S.; Bugaut X.; Constantieux T.; Bonne D.; Rodriguez J. α,β-Unsaturated Acyl Cyanides as New Bis-Electrophiles for Enantioselective Organocatalyzed Formal [3+3]Spiroannulation. Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 410–415. 10.1002/chem.201303613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Photis J. M. Halide-directed nitrile hydrolysis. Tetrahedron Lett. 1980, 21, 3539–3540. 10.1016/0040-4039(80)80228-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder A.; Aemmer T.; Indolese A. F.; Pittelkow U.; Studer M. First Application of Secondary Phosphines as Supporting Ligands for the Palladium-Catalyzed Heck Reaction: Efficient Activation of Aryl Chlorides. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2002, 344, 495–498. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For Vinylation of a 2-Bromopyridine with Ethylene, see:; a Detert H.; Sugiono E. Synthesis of Substituted 1,4-Divinylbenzenes by Heck Reactions with Compressed Ethene. J. Prakt. Chem. 1999, 341, 358–362. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]; For Vinylation of 3-Bromopyridines with Ethylene, see:; b Heck R. F. Palladium-Catalyzed Vinylation of Organic Halides. Org. React. 1982, 27, 345–390. [Google Scholar]; c Raggon J. W.; Snyder W. M. A Reliable Multikilogram-Scale Synthesis of 2-Acetamido-5-Vinylpyridine Using Catalytic BINAP in a Modified Heck Reaction. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2002, 6, 67–69. 10.1021/op010213o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Devries K. M.; Dow R. L.; Wright S. W.. Process for Substituted Pyridines. WO Patent WO9821184A1, May 22, 1998.; e Barlow H.; Buser J. Y.; Glauninger H.; Luciani C. V.; Martinelli J. R.; Oram N.; Hook N. T.-V.; Richardson J. Model Guided Development of a Simple Catalytic Method for the Synthesis of Unsymmetrical Stilbenes by Sequential Heck Reactions of Aryl Bromides with Ethylene. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018, 360, 2678–2690. 10.1002/adsc.201800167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; For Vinylation of a 4-Bromopyridine; f Southard G. E.; Van Houten K. A.; Murray G. M. Heck Cross-Coupling for Synthesizing Metal-Complexing Monomers. Synthesis 2006, 2475–2477. 10.1055/s-2006-942471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For Further Details of the Reaction Conditions Screening, see Supporting Information.

- For Ru- or Rh-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation, see:; a Uematsu N.; Fujii A.; Hashiguchi S.; Ikariya T.; Noyori R. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Imines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 4916–4917. 10.1021/ja960364k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Mao J.; Baker D. C. A Chiral Rhodium Complex for Rapid Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Imines with High Enantioselectivity. Org. Lett. 1999, 1, 841–843. 10.1021/ol990098q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pyo M. K.; Lee D.-H.; Kim D.-H.; Lee J.-H.; Moon J.-C.; Chang K. C.; Yun-Choi H. S. Enantioselective synthesis of (R)-(+)- and (S)-(−)-higenamine and their analogues with effects on platelet aggregation and experimental animal model of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4110–4114. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.05.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Martins J. E. D.; Redondo M. A. C.; Wills M. Applications of N′-alkylated derivatives of TsDPEN in the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of C=O and C=N bonds. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2010, 21, 2258–2264. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2010.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Shende V. S.; Deshpande S. H.; Shingote S. K.; Joseph A.; Kelkar A. A. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Imines in Water by Varying the Ratio of Formic Acid to Triethylamine. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 2878–2881. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For Ir-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation, see:; a Chang M.; Li W.; Zhang X. A Highly Efficient and Enantioselective Access to Tetrahydroisoquinoline Alkaloids: Asymmetric Hydrogenation with an Iridium Catalyst. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10679–10681. 10.1002/anie.201104476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xie J.-H.; Yan P.-C.; Zhang Q.-Q.; Yuan K.-X.; Zhou Q.-L. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Cyclic Imines Catalyzed by Chiral Spiro Iridium Phosphoramidite Complexes for Enantioselective Synthesis of Tetrahydroisoquinolines. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 561–564. 10.1021/cs300069g. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Berhal F.; Wu Z.; Zhang Z.; Ayad T.; Ratovelomanana-Vidal V. Enantioselective Synthesis of 1-Aryl-tetrahydroisoquinolines through Iridium Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation. Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 3308–3311. 10.1021/ol301281s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ružič M.; Pečavar A.; Prudič D.; Kralj D.; Scriban C.; Zanotti-Gerosa A. The Development of an Asymmetric Hydrogenation Process for the Preparation of Solifenacin. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012, 16, 1293–1300. 10.1021/op3000543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Commercially Available from Kanto Chemical Co., Inc. as RuCl[(R,R)-i-BuSO2dpen](p-cymene).

- a Hartwig J. F. Discovery and Understanding of Transition-Metal-Catalyzed Aromatic Substitution Reactions. Synlett 2006, 1283–1294. 10.1055/s-2006-939728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Surry D. S.; Buchwald S. L. Dialkylbiaryl phosphines in Pd-catalyzed amination: a user’s guide. Chem. Sci. 2011, 2, 27–50. 10.1039/C0SC00331J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein.

- Ley S. V.; Thomas A. W. Modern Synthetic Methods for Copper-Mediated C(aryl)–O, C(aryl)–N, and C(aryl)–S Bond Formation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5400–5449. 10.1002/anie.200300594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; and references therein.

- Klapars A.; Buchwald S. L. Copper-Catalyzed Halogen Exchange in Aryl Halides: An Aromatic Finkelstein Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 14844–14845. 10.1021/ja028865v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Scalability of Reactions with Gaseous Ammonia and Ethylene Has also been Demonstrated by Continuous Flow Processes, see:; a Pastre J. C.; Browne D. L.; O’Brien M.; Ley S. V. Scaling Up of Continuous Flow Processes with Gases Using a Tube-in-Tube Reactor: Inline Titrations and Fanetizole Synthesis with Ammonia. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2013, 17, 1183–1191. 10.1021/op400152r. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bourne S. L.; Koos P.; O’Brien M.; Martin B.; Schenkel B.; Baxendale I. R.; Ley S. V. The Continuous-Flow Synthesis of Styrenes Using Ethylene in a Palladium-Catalysed Heck Cross-Coupling Reaction. Synlett 2011, 2643–2647. 10.1055/s-0031-1289291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.