Abstract

Background

The trend of non-communicable diseases is alarmingly increasing and tobacco consumption and exposure to its smoke have been playing the leading role. Thirty-seven Ethiopians deaths per day are attributable to tobacco. Unless appropriately mitigated, this has social, economic and political impacts. Implementation of the appropriate policy is a good remedy; however, the policy process has never been straight forward and always successful. The involvement of different actors makes policy process complex hence agenda setting, policy formulation, implementation, and evaluations have been full of chaos and even may fail at any of these levels. Thus the aim of this review was retrospectively analyzing tobacco-related policies in Ethiopia that are relevant to control tobacco use and mitigate its impacts.

Methods

Systematically, we searched in pub-med, Scopus, Web of Science and Embase. Additionally, we did hand search on Google scholar and national websites. The terms “tobacco”, “cigar”, “cigarette”, “control”, “prevention”, “policy” and “Ethiopia” were used. Eleven of 128 records met the inclusion criteria and then included. For data analysis, we applied the health policy analysis framework developed by Walt and Gilson.

Result

Lately, Ethiopia enacted and started to implement tobacco control policies and programs, but its implementation is problematic and consumption rate is increasing.

Conclusion

Despite the early involvement in tobacco control initiatives and enactment of legal frameworks, Ethiopia's journey and current stand to prevent and control the devastating consequences of tobacco is very limited and unsatisfactory. Therefore, we strongly call for further action, strong involvement of private sector and non-governmental organizations.

Keywords: Tobacco prevention, tobacco control, retrospective, policy analysis, Ethiopia

Introduction

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are becoming major health threats to human beings across the globe while their impact is significant in developing countries due to weak preventive and promotive interventions (1). Fast socio-economic growth aligned with demographic and epidemiological transitions has been increasing the risks for and causes to NCD, particularly in developing countries like Ethiopia (2). Unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, tobacco use, and harmful alcohol consumption are the major modifiable behavioral risk factors that contribute to non-communicable diseases. Controlling these risky behaviors helps to prevent disease progression, complication occurrences and improves health status (3). About eighty percent of type II diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and stroke, and forty percent of cancers could be halted by managing these behavioral risk factors. If not, uncontrolled risk behavioral factors subsequently lead to severe biochemical risks, called intermediate-risk factors: such as high blood pressure, raised blood glucose, raised blood lipids and overweight and obesity (4). These risk conditions cause the greatest global share of death and disability, accounting for more than 63% of all deaths worldwide whereas 82% of these deaths related to chronic-disease take place in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (5). Rapid increases of disease burden from NCDs have significant economic, social and political implications whereas the burden is triple in resources limited settings like Ethiopia (6,7). Tobacco costs the global community more than 1.4 trillion USD every year which is 1.8 recent of the global annual gross domestic product (GDP). Nonetheless, the highest-burden is unbearably loaded on poorest people and countries (8).

Ethiopia is also among the countries where the trend of non-communicable diseases is alarmingly increasing to epidemic levels (3,6). A nationwide representative study conducted in the country revealed that sadly, only 1.6 percent of the study participants were free of NCD related behavioral and/or biological risk factors; tobacco use was one of the four major behavioral risk factors in the country (6).

Tobacco is the leading cause for the majority of NCD related morbidities and mortalities across the world (8,9). By the year 2015, there were 6.4 million deaths attributable to smoking which was 11.5% of deaths across the globe (10). Starting from 1990, smoking ranks second place of risk factors for premature death and disability and kills 5 million people yearly throughout the world (11). The prevalence of tobacco use in Ethiopia was estimated to be 5 percent for adults (five times males as compared to females) while about 8 percent of youths use tobacco products. Second-hand smock was 29.3 percent for adults and 31.1 percent for youths (12). Each week, 258 deaths are attributable to tobacco use in Ethiopia and evidence shows the death toll will increase in the future. Additionally, according to 2015 statistics, 6.2% of people continue to use tobacco each day which makes its impact as a major public health threat, and the economic cost of tobacco in Ethiopia is approximately US$50 million which was a significant portion of national GDP (13). Though the consequences and impact of tobacco are well understood in other countries, it is not yet well established; and sustainable monitoring and regulation of its level and trends have been lagging miles behind in Ethiopia. Thus, it is important to analyze the tobacco-related policies to find gaps and propose possible solutions.

Methods

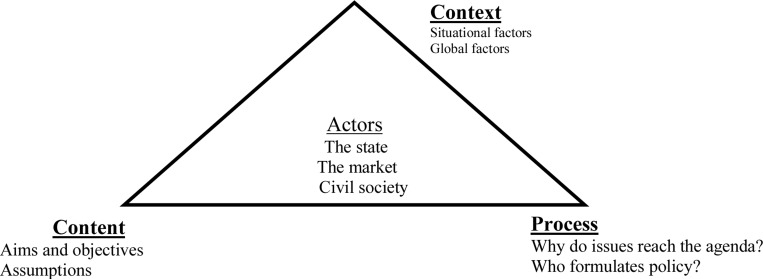

Study Design and search strategy: This article is a retrospective analysis of tobacco prevention and control laws, policies, programs, strategies and interventions in Ethiopia, and its focus area was presenting document analysis based on retrieved records from available sources. We conducted a comprehensive systematic search for documents that reported tobacco prevention and control policies in Ethiopia, using a systematic search approach that followed predetermined items for policy analysis. Searches were done in Pub-med, Scopus, Embase, and Web of Science databases from inception to 08 December 2019 for all relevant evidence. Additionally, search for a list of references cited by retrieved eligible documents was carried-out by hand search on Google Scholar and national websites. The search terms used include: ‘tobacco control’ OR ‘tobacco prevention’ OR ‘cigar control’ OR ‘cigar prevention’ OR ‘cigarette control’ OR ‘cigarette prevention’ OR ‘tobacco control and prevention’ OR ‘Cigar control and prevention’ OR ‘cigarette control and prevention’ combined with ‘policy’ OR ‘program’ OR ‘strategy’ OR ‘intervention’ and ‘Ethiopia’. There were no language or time limits applied during searching for documents. For data analysis, we applied the health policy analysis triangle framework developed by Walt and Gilson (14). This “policy triangle helps policymakers and researchers better understand the process of health policy reform retrospectively and to plan for more effective implementation prospectively” (15). The policy ‘triangle’ in the health policy analysis framework is not a binding theory of policy change - it is a very helpful way to assemble rich data to help to understand how the four policy decisions are made. It sensitizes the analyst to the possibility that policy change is the result of many factors. The framework has four constructs: content, context, process and actors/stakeholders. According to Walt G et al(15), the content is the substance of a particular policy, tobacco prevention and control policy in this paper, which details its constituent parts; context implies systemic factors which may have an effect on tobacco prevention and control policy such as political, economic, social or cultural at national and international levels; process is the way in which policies are initiated, developed or formulated, negotiated, communicated, implemented and evaluated while the term actors denotes individuals, organizations or even the state and their actions that affect tobacco prevention and control policy. Hence, we found that it was suitable for our analysis and presented in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Walt and Gilson's health policy analysis framework

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Documents were eligible for inclusion if they were documents of policy, programs, strategies, and interventions related to tobacco prevention and control in Ethiopia such as national proclamations, regulations, directives, guidelines, national mega plans, major survey reports and program documents. Otherwise, they were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis: After searching for the data in predetermined search sources, all the references were exported to Endnote X7(www.endnote.com). We used Microsoft word to record information from all qualifying records regarding the topic under analysis. In addition to the documents regarding the policies, programs, strategies, and interventions related to tobacco control and prevention, national proclamations, directives, guidelines, and survey reports were reviewed. eleven out of 128 documents: five proclamations (16–20), one regulation (21), one directive (22), one program document (23), two national comprehensive surveys reports (24,25), and one guideline (26) were eligible for this policy analysis hence included and presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

List and types of retrieved policy documents for policy analysis of tobacco control and prevention in Ethiopia, 2019

| Document type | Name of the document (author and year) |

| Program documents |

|

| Survey reports |

|

| Guidelines |

|

| Proclamations |

|

| Directive |

|

| Regulation |

|

Analysis: Thematically, we categorized and analyzed the documents: documents related to laws such as proclamations, directives, and regulations were analyzed chronologically and others were based on the themes under our study. Walt and Gilson's health policy analysis framework was applied to analyze the retrieved policy-related documents and presented accordingly.

Results

Content: Ethiopia's first tobacco-related proclamation was enacted and became effective in 1992 whilst the National tobacco enterprise of Ethiopia (NTE) was owned by the public. The 1992 proclamation gave, among other things, monopoly right to the state (18), and consequently, the government was the main actor in the tobacco market. The reason behind the monopoly might be its economic reward to the state. In 1999, the monopoly right was transferred to a shared company; however, the government involvement was high not only for the sake of the public's benefit but also for power control as well (17). Though the government was constitutionally granted with the power to take notable actions to improve the health of the people, the motive behind monopoly right transfer might be: external and internal pressures to liberalize the market. Other reasons for this were pushing the government's roles to focus on regulatory actions and safeguarding the system to improve the health of the people; international recognition of tobacco use harms on the health of people and the rising burden of NCDs (13). In 2007, broadcasting services licensing and compliance enforcement mandate were legally given to broadcasting authority and Ethiopian Food and Drug Administration (EFDA) (18); in 2014, tobacco product control regulation was ratified (21), and in 2015, smoking restrictions, tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship, tobacco packaging and labeling, and tobacco product regulation were enacted and became effective. However, it had many loopholes, and its implementation was questionable again (22). Nonetheless, in 2019, Food and Medicine Administration Proclamation No. 1112/2019 got strong legal foundations (20), and the proclamation more narrowed the major gaps of the previous proclamations. Hence, all the legal frameworks indicate that Ethiopia has been striving to move forward along with national and global changes and tried to align national health policy with internal and global policies to improve the health of the people, specifically to control tobacco use and mitigate its impacts on the health of Ethiopians. One of the indications for this point is the four successive health sector development plans and health sector transformation plan, more recently (23). However, these national mega plans did not incorporate the major risk factors control and preventions, including tobacco control, as it has got the concern of the international community due to the rising epidemics of NCDs across the world and in developing countries in particular. Additionally, the health sector transformation plan of Ethiopia was such a wide and deep national plan that included data for decision, leadership, empowerment, accountability, quality, and equity as its core components, but again it did not give any place for tobacco control rather than depicting some of NCDs. The major retrieved resources along with their aim and effective dates for this policy analysis are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Laws, regulations, directive and mega plans related to tobacco control in Ethiopia, 2019

| Document | aim | Effective date |

| Public Enterprises Proclamation No. 25/1992 |

Creating a legal framework for enterprises which aligns with the new national economic policy |

27th August 1992 |

| Monopoly Right transfer Proclamation No. 181/1999 |

Transferring monopoly right of purchase, preparation, manufacture, sale, import and export of tobacco and tobacco products to the National Tobacco Enterprise (Ethiopia) Share Company |

18th November 1999 |

| Broadcasting Service Proclamation No. 533/2007. |

To regulate broadcasting services & programs, and license and enforce compliance with tobacco advertisements by broadcasters |

23rd July 2007 |

| Advertisement Proclamation No.759/2012 |

To, among other things, prohibit cigarette or other tobacco products advertisement |

27th August 2012 |

| EFDA, Council of Ministers Regulation No. 299/2013 |

To, among other points, control tobacco products | 24th January 2014 |

| Tobacco Control Directive No. 28/2015 |

To, among other things, protect public health from the devastating health, social, environmental and economic consequences of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke. |

21st April 2015 |

| Food and Medicine Administration Proclamation No. 1112/2019 |

To, among other things, prevent and control the public's health from the devastating health, social, and economic consequences of tobacco product |

28th February 2019 |

| Ethiopia demographic and health survey 2016 |

to provide up-to-date estimates of key demographic and health indicators |

2017 |

| Health Sector Transformation Plan 2015/16 – 2019/20 |

To enhance, among other things, Policy and Procedures |

2015 |

| Ethiopian National Guideline on Major NCDs |

To, among other things, provide tobacco cessation guidelines |

2016 |

| Ethiopia NCD STEPS, 2015 | To assess risk factors for major non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and the prevalence of selected NCDs to establish baseline information for policy and program development |

2015 |

Process

Agenda setting: Agenda setting, according to Walt G et al, is a process by which certain issues come onto the policy agenda from the much larger number of issues potentially worthy of attention by policymakers, and we used this idea to analyze tobacco prevention and control policy in Ethiopia.

Shreds of evidence about the increasing level of non-communicable diseases across the world worried and forced national and international communities to think as well as work deeply to tackle the risk factors, including tobacco use and exposure to its smoke (10). Intensifying evidence, advancement in technologies, and increasing access to media helped people, scholars, and politicians to be more informed about the devastating effects of tobacco and exposure to its smoke. Public figures such as Prime Minister (1995 to 2012) Meles Zenawi publically spoke about the harmful social, economic and health consequences of cigarettes. Once he said on a public gathering “smoking a cigarette is not a sign of modernization, it is an indication of backwardness since it causes even irreversible problems”. Media started to air the world's stand against tobacco use and its potentially harmful effects on people's health, social, economic and environmental aspects (27, 28). Hence, the issues of tobacco become the agendas of politicians and scholars.

Additionally, Ethiopia as one of the active member states of WHO, signatory of UN human rights charters and WHO FCTC conventions, started to work closely with WHO and other stakeholders (26). The country actively participated in all WHO FCTC meetings; however, ratified WHO FCTC after ten years of its initiation (26). Furthermore, the reasons for prioritizing tobacco control agenda was the 2004 WHO FCTC and WHO's insistence on member parties to plan to prevent and control the devastating consequences of tobacco; recognition of tobacco use as one of contributing factors of NCDs and increasing trend of NCD related morbidity and mortality rates in the country (9,29). Whilst all the efforts and opportunities have been there, Ethiopia's tobacco control policies, programs, strategies, and interventions remain less worked and looking forward to strong and committed systems for its implementation.

Formulation: Policy formulation is generally about which policy alternatives and evidence are considered and/or why evidence is ignored. Hence, objectively our analysis focused on tobacco prevention and control policy matters. Our findings indicated that the formulation of all legal documents, policies, programs, and plans regarding tobacco prevention and control, reportedly, were based on Ethiopia's constitution; the WHO tobacco control convention, national evidence and consultations with major stakeholders. Moreover, the formulation phase incorporated the regulatory requirements and capacities within the country (23). Ethiopia actively took part in all WHO FCTC meetings; national advocacy meetings were held and cascaded to, at least, province levels; stakeholders participated and reached consensus (26). The training was given to key actors; planning was done; feedbacks were received and addressed accordingly. Finally, the responsibility to develop a national tobacco control directive was given to FMHACA, and it was endorsed based on legal and WHO FCTC frameworks. Although all these Ethiopia's policies and legal frameworks tried to consider and capture relevant issues, capabilities, socio-demographic, cultural, political and economic factors, it lacks full considerations of long-rooted traditional tobacco (?) smoking practices, specifically in some rural communities. Additionally, due to low tobacco smoking prevalence and relatively short duration since the initiation of the WHO FCTC, it might have missed considering the success histories and failures from other comparable countries and settings.

Implementation: Policy implementation is a process of turning policy into practice, here tobacco prevention and control policy. Ethiopia's national major non-communicable disease prevention and control guideline was developed and collaboration with relevant actors was an integral part of its implementation. The Federal Ministry of Health (FMoH), FMHACA, PFSA, and regional health bureaus (RHBs) started to collaborate, coordinate, engage and facilitate relevant stakeholders for the implementation of tobacco control policies and programs. Moreover, “FMoH and RHBs are also expected to endeavor to establish healthcare facilities and rehabilitation centers with programs for diagnosing, counseling, preventing and treating tobacco dependence” (26). Though there are loopholes during implementations, Ethiopia has relatively good tobacco control policies and programs. For example, the country banned any type of tobacco and the promotion of its products by mass media by 2019. However, the country's loudly spoken tobacco control policies, programs, strategies, and interventions have had paper tiger values and the mere implementations have been left behind. For instance, although it is legally restricted to promote tobacco by any means (20,30,31), pieces of evidence show tobacco promotion through different mechanisms such as clothing or other items with a cigarette brand name or logo, free distribution, etc are common in the country. Moreover, although a wide range of global, national and local actors have been participating to control and prevent tobacco use and mitigate its impacts, it became clear that the progress and comprehensive response remain a challenge and sustained issue of vast importance that has been inadequately addressed public health issue of the 21st century. Hence, if Ethiopia strives to achieve the goal of tobacco control, a lot has to be done and needs many efforts as well as adequate resources.

Evaluation: Tobacco prevention and control Policy Evaluation is generally about whether and why the policies achieve their aims. Until 2015, STEPS report on risk factors for noncommunicable disease and prevalence of selected non-communicable diseases, in Ethiopia, there were no representative studies, except pocket surveys in some parts of the country (24). The 2015 survey result showed that tobacco use was five percent in the country and there was no difference in rural and urban settings. According to this report, there were tobacco promotions in different forms such as giving a free sample of cigarettes, gifts or special discounts, clothing or other items with cigarette brand names or logo and through mails while only one-fourth of the smokers noticed the warnings on cigarettes (24). Until today, we could not find pieces of evidence that show the status of tobacco control policy implementation and that evaluates its effects. The implementation status, progress of implementation, and program effectiveness evaluation and indicators are not yet well established in the country. Furthermore, the national guideline of 2016 was not comprehensive and it mainly focuses on clinical management of tobacco dependence. Thus, it needs revision.

Context: Ethiopia is the second-most populous Africa country with 110,135,635 populations in 2019 and ranks 12th in the world. One-fifth of Ethiopians live in urban areas and the rest are rural inhabitants (4, 32). The country has a fast-growing population size and its economy is booming in recent years (32, 33). Despite the fast-growing population size and socio-economic development, the country has a short history of modern health care systems where the first modern public hospital was built in 1906 and the Ministry of Health established in 1948(34). A decentralized and federal system was established by 1991 which could be considered as a starting point for the new era of transformation in political and socio-economic aspects. Among these was the development of the first national health policy in 1993 (35), which gave a foundation to the initiation of four successive comprehensive Health Sector Development Plans (HSDPs), having a 5 year period each that begun in 1997. The primary focuses and achievements of Ethiopia's health sector are prevention and controlling major communicable diseases and strengthening health promotion activities however non-communicable diseases and its major risk factors did not get appropriate weights (34, 36).

Whilst long, decisive steps have been underway to improve the health sector performance and ultimately the health status of the people since 1990s, Ethiopia's population up to the present days suffers high rates of morbidities and mortalities from preventable and manageable health-related causes, and consequently, the health status of the people remains very poor (37). Additionally, the recent political instability might have been playing its hindering role for the implementation as well as the evaluation of policies in the country. Hence, the contextual factors that can influence the implementation of tobacco prevention and control policies in Ethiopia are social, cultural, political and administrative problems.

The socio-cultural factors that might have been influencing the implementation of the tobacco control policies and programs could be long stayed traditional tobacco use practices among rural communities; very low literacy and health literacy levels of the population; consideration of smoking as sign of modern lifestyle by urban youths and adolescents, and unregulated risky practices around the higher education surroundings, particularly universities and colleges.

The political and administrative factors, among other things, include the recent volatile and unstable political situations that has been happening in the country, lack of capabilities to implement and regulate, poor coordination and cooperation amongst stakeholders, lack of reporting and monitoring procedures, weak infrastructure, high turnover and skill gaps particularly at lower implementation levels, lack of expertise and low involvement of private sector and poor collaborations between public and private sectors.

Despite the growing economy of Ethiopia, the gap between the rich and the poor remains wide and the country's economic growth is not yet stable and inclusive (38). Hence, the economic factors affecting tobacco prevention and control are miscellaneous. For instance, Ethiopia's high dependence on foreign loans and aids, poor financial support and expenditure on health by the government; shift of giant global tobacco industries from high-income countries to middle and low-income countries and attractive employment opportunities by these industries could be some of the main. Furthermore, the lack of well organized internal financial mobilization systems and inaccessibility of healthy lifestyles are extra obstacles behind its poor implementation.

Actors: The actors are those interest groups or individuals that influence the policy from its initiation to implementation and evaluation. The major interest groups and/or actors of tobacco control and prevention policy in Ethiopia, amongst many others, include World Trade Organization (WTO), WHO, World Bank (WB), Prime Minister, FMOH, regional health bureaus (RHBs), FMHACA, Ministry of Health, EPHI, EPHA, Pharmaceutical Fund and Supply Agency (PFSA), Civil society, Admin cadre, Media/press, Religious institutions, Academia, Ministry of finance, Tobacco industries (e.g. NTE), Employee of tobacco industries, Health NGOs and tobacco users. Their positions and level of influence are analyzed in Table 3. Most of the stakeholders listed here are internal and some of them are global stakeholders, but we could not find any pieces of data which show the active involvement of private sectors from the policy initiation to its implementation and evaluation in Ethiopia. The reason for this might be that we could not get opportunities to look at grey literature. There exists, though late, policy and regulatory interventions to promote a healthy life, prevent and control tobacco smoking in Ethiopia, but it lacks full implementation or enforcement. The available evidence indicates that policies and programs for tobacco use control and prevention in Ethiopia have been evolving and the attitudes of stakeholders towards the prevention and control of tobacco appear more positive, particularly, after the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) (39). While this is true as long as the policies and programs are concerned and stakeholders are engaged, in the actual execution of the policies and programs there continues to be notable gaps and uncertainties regarding the implementation of these policies in Ethiopia. Besides, most of the giant tobacco industries have been shifting from developed to developing countries to increase their market shares(40). The industries have capacities to interfere, lobby and influence the already weak regulatory and enforcement structures in those countries, including Ethiopia. Thus, they are looking for loopholes in the host countries' policies that may give them opportunities to increase their influence on regulatory systems(41,42). Unless strong periodic monitoring of tobacco smoking, evaluation of tobacco control intervention and sustained vigilance on tobacco industry interventions are implemented, the impact of tobacco use will continue to claim the lives of thousands.

Table 3.

Stakeholder analysis for retrospective policy analysis of tobacco control and prevention in Ethiopia, 2019

| Their position | ||||

| Opposes | Neutral | Support | ||

| Level of influence | High | Tobacco industries (NTE) |

Media/press | WHO, WB, Prime Minister, FMOH, RHBs, FMHACA, Minister of health, EPHI, EPHA |

| Medium | WTO, Tobacco users | Minister of finance | Religious institution, Admin cadre, Academia |

|

| Low | Employees of tobacco industries, |

Civil society | PFSA, Health NGOs | |

The level of public awareness regarding regulations and prohibitions of tobacco use and its devastating health consequences remain very low in Ethiopia (24,43). This finding agrees with lessons from other countries in Africa and around the world (44,45). Likewise, packaging and labeling have not been well regulated; the tobacco industries are not taking feasible actions to install self-regulations in Ethiopia as well as in other developing countries. Additionally, in Ethiopia, most healthcare facilities that can treat tobacco dependence for addicted individuals lack necessary supplies(26), and hence, comprehensive and consistent policies should be enforced; leadership commitment is needed; capacity building of implementers, and strong and committed system should be established in the country.

Evidence from other countries indicated the importance to increase or introduce health taxes on tobacco as one of the effective strategies to reduce its use (46) which is also important to deal with this public problem by reducing affordability in Ethiopia as well. Moreover, alternative mechanisms such as awareness creation, mass-education, putting legal restrictions and fine for illegal things or sale for under-ages as well as promotion banning are critically important factors in the country. Although late, Ethiopia enacted a full smoking ban in all enclosed workplaces, including catering and drinking establishments, and all public buildings and transport to protect the health of non-smokers and employees and this is in line with lessons in other countries (47).

In conclusion, Ethiopia is one of the active members and signatory of WHO FCTC framework and endorsed the tobacco control policy in 2014. Despite the early involvement in tobacco control initiatives and long distances the country walked to enact legal frameworks since the late 1990s, Ethiopia's journey and current stand to prevent and control the devastating consequences of tobacco is very limited and unsatisfactory. Ethiopia's policy on tobacco control is more inclined to accountability rather than contextual comprehensive response and prospects. Only having a policy at national and/or lower levels is not a guarantee to control the rising epidemics of the NCDs due to shared behavioral risk factors like tobacco use and exposure to its smoke. The national guideline developed mainly focuses on clinical management of tobacco dependence, to achieve the desired goal of tobacco control; it needs to be revised to make it more comprehensive and/or preventive strategies should be incorporated as a priority of the public sector, and the private sector should be engaged.

As it is indicated in WHO FCTC, to adopt adjustable simple taxation and other structural arrangements (8,39) and given the high pressures, economical and market control, from tobacco industries, increasing public awareness and strengthening the regulatory systems, including lawyers, seems very relevant and tobacco taxation should be mandated. Therefore, it is strongly recommended to strengthen the implementation of the policy, programs, strategies and intervention, information education and advocacy in the country.

The limitations of this policy analysis were that the whole procedures depended on internet-based data sources, and it did not include grey documents but we tried to capture all relevant documents through manual searches from cited references.

References

- 1.Gebre-Yohannes A, Rahlenbeck SI. Glycaemic control and its determinants in diabetic patients in Ethiopia. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 1997;35(2–3):129–134. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(96)01367-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu FB. Globalization of diabetes: the role of diet, lifestyle, and genes. Diabetes care. 2011;34(6):1249–1257. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization WH, author. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization;; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ethiopia, author. YaṬénā ṭebaqā mr. HSTP Health Sector Transformation Plan: 2015/16 – 2019/20 (2008–2012 EFY) 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daar AS, Singer PA, Persad DL, et al. Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature. 2007;450(7169):494. doi: 10.1038/450494a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abate Ebba, Getachew Theodros, Tamiru Adugna, et al. Health Data Quality Review: System Assessment and Data Verification. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Public Health Institute; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reubi D, Herrick C, Brown T. The politics of non-communicable diseases in the global South. Health & Place. 2016;39:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Organization WH, author. Global progress report on the implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Organization WH, author. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2017: monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies. World Health Organization; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reitsma MB, Fullman N, Ng M, et al. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–1906. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forouzanfar MH, Afshin A, Alexander LT, et al. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioral, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1659–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization-Regional Office for Africa, author. The Toll of Tobacco in Ethiopia - Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. 2017. online database. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drope J SN, Cahn Z, Drope J, et al. The Tobacco Atlas. Publisher's Cataloging-in-Publication Data. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walt G, Shiffman J, Schneider H, et al. ‘Doing’ health policy analysis: methodological and conceptual reflections and challenges. Health Policy and Planning. 2008;23(5):308–317. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czn024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. Making health policy. UK: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zenawi Meles. Public Enterprises law Proclamation No. 25/1992. Negarit Gazeta, 1992-08-27, No 21. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: 1992. pp. 124–138. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gidada Negaso. Transfer of the Monopoly Right of the National Tobacco Enterprise to the National Tobacco Enterprise (Ethiopia) share Company proclamation No. 181/1999. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Negarit Gazeta of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woldegiorgis Girma. Broadcasting Service Proclamation No. 533/2007. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Negarit Gazeta of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woldegiorgis Girma. Advertisement Proclamation No.759/2012. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal negarit gazeta of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zewde Sahlework. Food and Medicine Administration Proclamation No. 1112/2019. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Negarit Gazeta of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desalegn Hailemariam. Food, Medicine and Health Care Administration and Control Council of Ministers Regulation No. 299/2013. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Negarit Gazeta of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denekew Yehulu. Tobacco Control Directive No 28/2015. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Federal Negarit Gazeta of the federal democratic republic of Ethiopia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Admasu Kesete-Birhan. Health sector transformation plan (2015/16-2019/20) Ministry of Health Addis Ababa; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kebede Worku YSMK, Kebede Amha, et al. Ethiopia STEPS report on risk factors for noncommunicable diseases and prevalence of selected NCDs: 203. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 25.ICF, CSACE, author. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: CSA and ICF; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.G/Michael M, Dagnaw W, Yadeta D, et al. Ethiopian National Guideline on Major NCDs. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Achia TN. Tobacco use and mass media utilization in sub-Saharan Africa. PloS one. 2015;10(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Organization WH, author. The WHO framework convention on tobacco control: an overview. 2015. http://www.WHO.int/fctc.WHO_FCTC_summary_January 2015_EN.pdf.

- 29.Eticha T, Kidane F. The prevalence of and factors associated with current smoking among College of Health Science students, Mekelle University in northern Ethiopia. PloS one. 2014;9(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ethiopia W, United States of America, author. Ethiopia Details Tobacco Control Laws. Website. 2019.

- 31.Erku DaT, Eyasu, author. Tobacco control and prevention efforts in Ethiopia pre- and postratification of WHO FCTC: Current challenges and future directions. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2019 Feb;17 doi: 10.18332/tid/102286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Group WB, author. The economic overview, Ethiopia. Washington (DC): The World Bank Group; 2019. [2 May 2019]. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tadesse T, Zawdie B. Non-compliance and associated factors against smoke-free legislation among health care staffs in governmental hospitals in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: an observational cross-sectional study. BMC public health. 2019;19(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6407-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adugna A. health institutions and services. 2014. [1 May 2019]. www.EthioDemographyAndHealth.Org. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richard G. Reviewing Ethiopia's health system development. JMAJ. 2009;52(4):279–286. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brathwaite R, Addo J, Smeeth L, et al. A Systematic Review of Tobacco Smoking Prevalence and Description of Tobacco Control Strategies in Sub-Saharan African Countries; 2007 to 2014. PloS one. 2015;10(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zeleka Paulos AZ, Pigois Remy, Belew Fantahun. National health and nutrition sector budget brief: 2006–2016: Ethiopia. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daie GF. Ethno-culture Disparity in Food Insecurity Status: The Case of Bullen District, Benishangul-gumuz Regional State, Ethiopia. African Journal of Food Science. 2014;8(2):54–63. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Organization WH, author. WHO framework conventions on tobacco control. WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomori O, Omaswa F, Bekure S, et al. Preventing a tobacco epidemic in Africa: a call for effective action to support health, social, and economic development. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization, author. Tobacco industry interference with tobacco control. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore S, Wolfe SM, Lindes D, Douglas CE. Epidemiology of failed tobacco control legislation. Jama. 1994;272(15):1171–1175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petersen AB, Thompson LM, Dadi GB, et al. An exploratory study of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs related to tobacco use and secondhand smoke among women in Aleta Wondo, Ethiopia. BMC women's health. 2018;18(1):154. doi: 10.1186/s12905-018-0640-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaur J, Jain D. Tobacco control policies in India: implementation and challenges. Indian journal of public health. 2011;55(3):220. doi: 10.4103/0019-557X.89941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yach D, editor. Tobacco in Africa. World health forum. 1996;17(1):29–36. 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaloupka FJ, Yurekli A, Fong GT. Tobacco taxes as a tobacco control strategy. Tobacco control. 2012;21(2):172–180. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Griffith G, Welch C, Cardone A, Valdemoro A. The global momentum for smoke-free public places: best practice in current and forthcoming smoke-free policies. Salud Publica de Mexico. 2008;50(S3):299–308. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342008000900006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]