Abstract

Background

Recently, the endothelial Activation and Stress Index (EASIX) score has been reported to predict overall survival (OS) after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. This study evaluated the prognostic role of EASIX score in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

Methods

This retrospective study analyzed the records of 1177 patients with newly diagnosed MM between February 2003 and December 2017 from three institutions in the Republic of Korea. Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine, and platelet count at diagnosis were measured in all included patients. EASIX scores were calculated using the formula-LDH (U/L) × Creatinine (mg/dL) / platelet count (109/L) and were evaluated based on log2 transformed values.

Results

The median age of patients was 63 years (range, 22–92), and 495 patients (42.1%) underwent autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT). The median log2 EASIX score at diagnosis was 1.1 (IQR 0.3–2.3). Using maximally selected log-rank statistics, the optimal EASIX cutoff value for OS was 1.87 on the log2 scale (95% CI 0.562–0.619, p < 0.001). After median follow-up for 50.0 months (range, 0.3–184.1), the median OS was 58.2 months (95% CI 53.644–62.674). Overall, 372 patients (31.6%) showed high EASIX scores at diagnosis, and had significantly inferior OS compared to those with low EASIX (log2 EASIX ≤1.87) (39.1 months vs. 67.2 months, p < 0.001). In multivariate Cox analysis, high EASIX was significantly associated with poor OS (HR 1.444, 95% CI 1.170–1.780, p = 0.001). In the subgroup analysis of patients who underwent ASCT, patients with high EASIX showed significantly inferior OS compared to those with low EASIX (52.8 months vs. 87.0 months, p < 0.001). In addition, in each group of ISS I, II, and III, high EASIX was associated with significantly inferior OS (ISS 1, 45.2 months vs. 76.0 months, p = 0.001; ISS 2, 42.3 months vs. 66.5 months, p = 0.002; ISS 3, 36.8 months vs. 55.1 months, p = 0.001).

Conclusion

EASIX score at diagnosis is a simple and strong predictor for OS in patients with newly diagnosed MM.

Keywords: Multiple myeloma, Prognosis, LDH, Platelets, Serum creatinine

Background

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a monoclonal plasma cell proliferation disorder with various symptoms and signs caused by monoclonal proteins [1]. Recent molecular studies have shown that MM is a genetically heterogeneous disease. In addition, clonal evolution and additional genetic events during the disease course affect the progression of the asymptomatic state to symptomatic disease and lead to a refractory disease state [2, 3]. Therefore, MM remains an incurable disease and shows various survival outcomes despite the development of new effective agents such as immunomodulatory drugs (IMids), proteasome inhibitors, and monoclonal antibodies. The most common staging system to predict the prognosis of MM is the Revised International Staging System (R-ISS) [4]. The R-ISS was created by incorporating the chromosomal abnormalities and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the original ISS and improved the prognostic power compared with the original ISS, cytogenetics, and LDH alone. However, cytogenetic abnormalities in the R-ISS do not include all the genetic abnormalities in MM and can be only assessed in selected institutions that can conduct gene analysis. For these reasons, there are still unmet needs about establishing a precise and convenient risk stratification model for MM.

Recently, a Germany and the United States (US) group presented the Endothelial Activation and Stress Index (EASIX), which is calculated by the formula-LDH (U/L) × Creatinine (mg/dL) / platelet count (109/L) as a reliable factor to predict the prognosis of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation [5]. They subsequently proposed that EASIX could predict the survival outcome in lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome which is not a candidate for allogeneic stem cell transplantation [6]. The prognostic impact of EASIX in allogeneic stem cell transplantation was externally validated in generalized population cohorts [7–9]. Platelet count, serum creatinine and LDH, which make up EASIX, are well-known prognostic factors for MM. Therefore, we planned this study to determine whether EASIX could also be useful to predict the survival outcomes for MM.

Methods

Patients

For this retrospective study, we analyzed the records of 1260 patients with newly diagnosed MM between February 2003 and December 2017 from three institutions in the Republic of Korea. Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance (MGUS), non-secretory MM, amyloidosis, and plasma cell leukemia were excluded. Additionally, 83 patients with lack of laboratory data such as serum LDH, serum creatinine or platelet count at diagnosis were excluded and finally 1177 patients were included in the analysis. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each participating institution and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ISS and EASIX analysis

ISS, R-ISS, and EASIX were assessed at initial diagnosis. Chromosomal abnormalities (CA) were evaluated based on conventional cytogenetic studies or fluorescence in situ hybridization. High-risk CA was characterized by the presence of at least one of del(17p), t(4;14), or t(14;16). Standard-risk CA was characterized by the absence of previously mentioned abnormalities. EASIX score was calculated by the formula-LDH (U/L) × Creatinine (mg/dL) / platelet count (109/L) and evaluated based on log2 transformed values.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s χ2 test and the Mann–Whitney U test were used for discrete and continuous variables to compare the patient characteristics. The primary end point was overall survival (OS), defined as the time from diagnosis to death as a result of any cause, or to the last follow-up date. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate the OS, and the survival curves were compared using a log-rank test. Maximally selected log-rank statistics using exactGauss [10] were applied to calculate an optimal cutoff in survival distributions according to EASIX. The prediction error curves and concordance index curves are estimated using the statistical software R (version 3.3.3), together with R packages survival (version 2.41–2), prodlim (version 1.6.1), maxstat (version 0.7–25), riskRegression (version 1.1.7) and pec (version 2.5.3) for statistical calculation. The estimate of the relative risk of an event and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for OS were assessed by univariate and multivariate analyses using a Cox proportional hazard model. The Cox proportional hazard model was calculated using log2 transformed index of EASIX It means that a hazard ratio of 1.25 corresponds to a 25% increase of the hazard for a two-fold increase of EASIX or one-fold increase of log2(EASIX). All statistical computations were performed using SPSS software (ver. 25; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, ISA) and R (version 3.3.3). A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant in all of the analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics and treatments

The median age of the patients was 63.0 years (range, 22.0–92.0), and 44.9% were older than 65 years. The most prevalent MM type was IgG (54.9%), and 21.2% of patients had light chain disease. Of the patients, 210 patients (17.8%) had serum creatinine level ≥ 2.0 mg/dL at diagnosis. Of the patients, 137 patients (26.5%) were classified as ISS I, 34.6% as ISS II, and 38.9% as ISS III. By applying the R-ISS, 213 (19.3%), 696 (62.9%), and 197 (17.8%) patients were assigned as stage I, II, and III, respectively. Chromosome analysis or FISH results were assessed in 1040 patients (88.4%), and 12.8% were classified as the high-risk cytogenetic group.

Overall, 424 patients (36.3%) received an IMid-based regimen as primary therapy, which is composed of thalidomide and dexamethasone (TD), or cyclophosphamide, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (CTD). Further, 371 patients (31.5%) received a proteasome inhibitor (PI)-based regimen as primary therapy, composed of bortezomib and dexamethasone (VD), or bortezomib, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone (VCD) or bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone (VMP). Additionally, 103 patents (8.8%) received a combination regimen with PI and IMid as primary therapy, composed of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone (VTD). Further, 261 patients (22.3%) received vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (VAD) or cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, or prednisolone as primary therapy. Four patients were treated with ixazomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone as primary therapy. One patient was treated with carfilzomib and one was treated with daratumumab.

During the entire treatment period, 903 patients (76.7%) underwent treatment with IMiDs such as thalidomide, lenalidomide or pomalidomide. Otherwise, 1010 patients (85.8%) were treated with PIs such as bortezomib, carfilzomib or ixazomib. Fifty-nine (5.0%) patients underwent daratumumab treatment. Autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) was performed in 495 patients (42.1%).

Individual EASIX and survival outcomes

EASIX was calculated in all patients at diagnosis, and the median log2 EASIX score was 1.1 (IQR 0.3–2.3). The optimal EASIX cutoff value for OS was determined at 1.87 on the log2 scale using maximally selected log-rank statistics (95% CI 0.562–0.619, p < 0.001). Three hundred and seventy-two patients (31.6%) were classified as high EASIX (log2 EASIX > 1.87), and 805 (68.4%) were classified as low EASIX (log2 EASIX ≤1.87). Differences of the baseline clinical characteristics between the high EASIX group and low EASIX group patients are presented in Table 1. When compared with patients who had low EASIX, patients with high EASIX at diagnosis had a more advanced stage disease according to the ISS and R-ISS. High EASIX group patients had more adverse risk factors such as high-risk CA, poor performance score (PS), hypercalcemia, anemia, and renal insufficiency. Patients in the high EASIX group also received fewer ASCT than patients in the low EASIX group. There were no differences in the number of patients with cardiovascular disease or liver disease between the high EASIX group and low EASIX group (cardiovascular disease, 6.0% vs. 4.5%, p = 0.375; liver disease, 2.3% vs. 1.6%, p = 0.303).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline clinical characteristics (High EASIX vs. Low EASIX)

| High EASIX (log2 EASIX > 1.87) (n = 372) |

Low EASIX (log2 EASIX ≤1.87) (n = 805) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 65 | 170 (45.7) | 359 (44.7) | 0.753 |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||

| Male | 234 (62.9) | 405 (50.3) | |

| Female | 138 (37.1) | 400 (49.7) | |

| Immunoglobulin (Ig) type | < 0.001 | ||

| Ig G | 162 (45.8) | 453 (59.3) | |

| Ig M | 2 (0.6) | 5 (0.6) | |

| Ig A | 67 (18.9) | 168 (22.0) | |

| Ig D | 11 (3.1) | 13 (1.7) | |

| Light chain only | 112 (31.6) | 125 (16.4) | |

| ECOG PS ≥ 2 | 92 (24.7) | 157 (19.5) | 0.046 |

| Calcium ≥10.2 mg/dl | 103 (27.8) | 82 (10.2) | < 0.001 |

| Hb < 10.0 g/dl | 273 (73.4) | 389 (48.3) | < 0.001 |

| Chromosomal abnormality | < 0.001 | ||

| High risk | 63 (16.9) | 71 (8.8) | |

| Standard risk | 262 (70.4) | 650 (80.7) | |

| Non-assessable | 47 (12.6) | 84 (10.4) | |

| ISS | < 0.001 | ||

| I | 21 (5.6) | 286 (35.5) | |

| II | 73 (19.6) | 328 (40.7) | |

| III | 271 (72.8) | 180 (22.4) | |

| Non-assessable | 7 (1.9) | 11 (1.4) | |

| R-ISS | < 0.001 | ||

| I | 7 (1.9) | 206 (25.6) | |

| II | 181 (48.7) | 515 (64.0) | |

| III | 162 (43.5) | 35 (4.3) | |

| Non-assessable | 22 (5.9) | 49 (6.1) | |

| Year of diagnosis | 0.073 | ||

| 2003–2005 | 24 (6.5) | 79 (9.8) | |

| 2006–2008 | 48 (12.9) | 135 (16.8) | |

| 2009–2011 | 84 (22.6) | 168 (20.9) | |

| 2012–2014 | 128 (34.4) | 233 (28.9) | |

| 2015–2017 | 88 (23.7) | 190 (23.6) | |

| ASCT | 128 (34.4) | 367 (45.6) | < 0.001 |

| Treatment regimen during entire treatment | |||

| Thalidomide-based therapy | 195 (52.4) | 513 (63.7) | < 0.001 |

| Lenalidomide-based therapy | 153 (41.1) | 461 (57.3) | 0.612 |

| Pomalidomide-based therapy | 49 (13.2) | 90 (11.2) | 0.332 |

| Bortezomib-based therapy | 317 (85.2) | 682 (84.7) | 0.861 |

| Carfilzomib-based therapy | 35 (9.4) | 77 (9.6) | 1.000 |

| Daratumumab-based therapy | 19 (5.1) | 40 (5.0) | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: n Number, ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, LDH Lactate Dehydrogenase, UNL Upper limit of the normal value, Hb Hemoglobin, ISS International Staging System, R-ISS Revised-International Staging System, ASCT Autologous stem cell transplantation

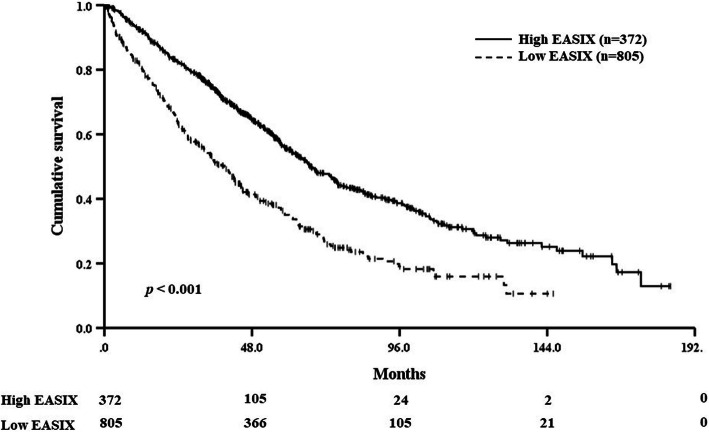

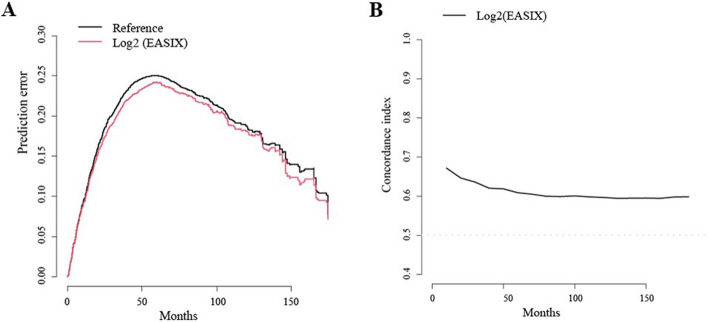

After median follow-up for 50.0 months (range, 0.3–184.1), median OS was 58.2 months (95% CI 53.644–62.674). Patients with high EASIX score at diagnosis had significantly inferior OS compared to the patients with low EASIX [39.1 months (95% CI 34.1–44.1) vs. 67.2 months (95% CI 61.2–73.1), p < 0.001, Fig. 1]. We validated the prognostic value of EASIX for overall survival by calculating the prediction error curve and concordance index curve (Fig. 2). In the univariate Cox analysis, the risk of death was increased for high EASIX versus low EASIX (HR 1.878, 95% CI 1.600–2.205, p < 0.001). In multivariable analysis, including age, sex, ECOG PS, hemoglobin, calcium, EASIX, ISS, and high-risk CA, the risk of death was increased for patients aged more than 65 years (HR 1.476, 95% CI 1.245–1.750, p < 0.001), PS score greater than 1 (HR 1.495, 95% CI 1.240–1.802, p < 0.001), high EASIX (HR 1.444, 95% CI 1.170–1.780, p = 0.001), and high-risk CA (HR 1.565, 95% CI 1.241–1.973, p < 0.001). The univariate and multivariable Cox analysis results are summarized in Table 2. The univariate and multivariate Cox analysis including Log2 EASIX as a continuous variable showed that the Log2 EASIX could also predict survival outcome as a continuous variable (HR 1.189, 95% CI 1.113–1.269, p < 0.001, Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival according to Endothelial Activation and Stress Index (EASIX) score

Fig. 2.

Prediction error curve (a) and time-dependent concordance index (b) for overall survival. A concordance index of 0.5 (dotted line) implies random concordance

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox analysis for overall survival (n = 1177)

| Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p - value | HR | 95% CI | p - value | |

| Age > 65 | 1.482 | 1.266–1.734 | < 0.001 | 1.476 | 1.245–1.750 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 1.178 | 1.008–1.377 | 0.039 | 1.097 | 0.926–1.299 | 0.284 |

| ECOG PS ≥ 2 | 1.648 | 1.385–1.961 | < 0.001 | 1.495 | 1.240–1.802 | < 0.001 |

| Hb < 10.0 g/dL | 1.271 | 1.086–1.488 | 0.003 | 1.030 | 0.852–1.244 | 0.763 |

| Calcium ≥10.2 mg/dL | 1.372 | 1.117–1.686 | 0.003 | 1.124 | 0.896–1.409 | 0.312 |

| Diagnosis at 2009–2014a | 0.638 | 0.386–1.054 | 0.079 | |||

| Diagnosis at 2015–2017a | 0.641 | 0.388–1.062 | 0.084 | |||

| Log2 EASIX > 1.87 | 1.878 | 1.600–2.205 | < 0.001 | 1.444 | 1.170–1.780 | 0.001 |

| ISS 2b | 1.361 | 1.527–2.300 | < 0.001 | 1.226 | 0.966–1.557 | 0.094 |

| ISS 3b | 1.874 | 1.101–1.682 | < 0.001 | 1.309 | 1.000–1.714 | 0.050 |

| High-risk CA | 1.838 | 1.469–2.300 | < 0.001 | 1.565 | 1.241–1.973 | < 0.001 |

Abbreviations: ECOG PS Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status, Hb Hemoglobin, EASIX Endothelial Activation and Stress Index, ISS International Staging System, R-ISS Revised-International Staging, System, CA Chromosomal abnormality

a Diagnosis at 2003–2008 is the reference

bISS 1 is the reference

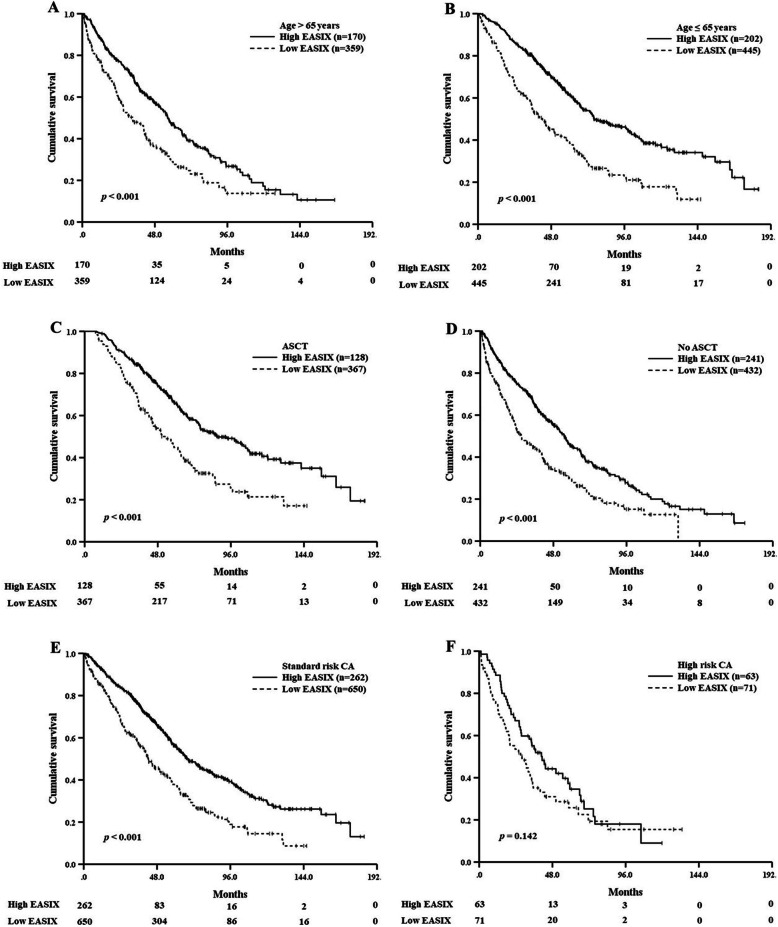

Subgroup analyses for OS were also performed to define the prognostic role of EASIX in patients younger and older than 65 years of age, in patients who did and who did not receive ASCT, and in patients with high- and standard-risk CA. Patients with high EASIX showed significantly shorter OS than patients with low EASIX, regardless of age [Age > 65 years, 33.2 months (95% CI 23.8–42.7) vs. 56.5 months (95% CI 49.5–63.6), p < 0.001; Age ≤ 65 years, 42.1 months (95% CI 32.8–51.4) vs. 76.0 months (95% CI 60.4–91.6), p < 0.001, Fig. 3a and b], regardless of ASCT [ASCT, 52.8 months (95% CI 41.4–64.2) vs. 87.0 months (95% CI 69.5–104.6), p < 0.001; No ASCT, 26.9 months (95% CI 20.2–33.6) vs. 55.2 months (95% CI 48.4–62.0), p < 0.001, Fig. 3c and d]. Regarding CA, high EASIX was associated with poor OS in the standard-risk CA group [42.3 months (95% CI 35.8–48.9) vs. 68.4 months (95% CI 60.6–76.1), p < 0.001, Fig. 3e], but was not statistically significant in the high-risk CA group [28.1 months (95% CI 15.2–40.9) vs. 41.3 months (95% CI 31.4–51.2), p = 0.142, Fig. 3f].

Fig. 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival according to the Endothelial Activation and Stress Index (EASIX) score (a) in patients aged > 65 years, (b) in patients aged ≤65 years, (c) in patients who underwent autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), (d) in patients who did not receive ASCT, (e) in patients with standard cytogenetic abnormalities (CA), and (F) in patients with high-risk CA

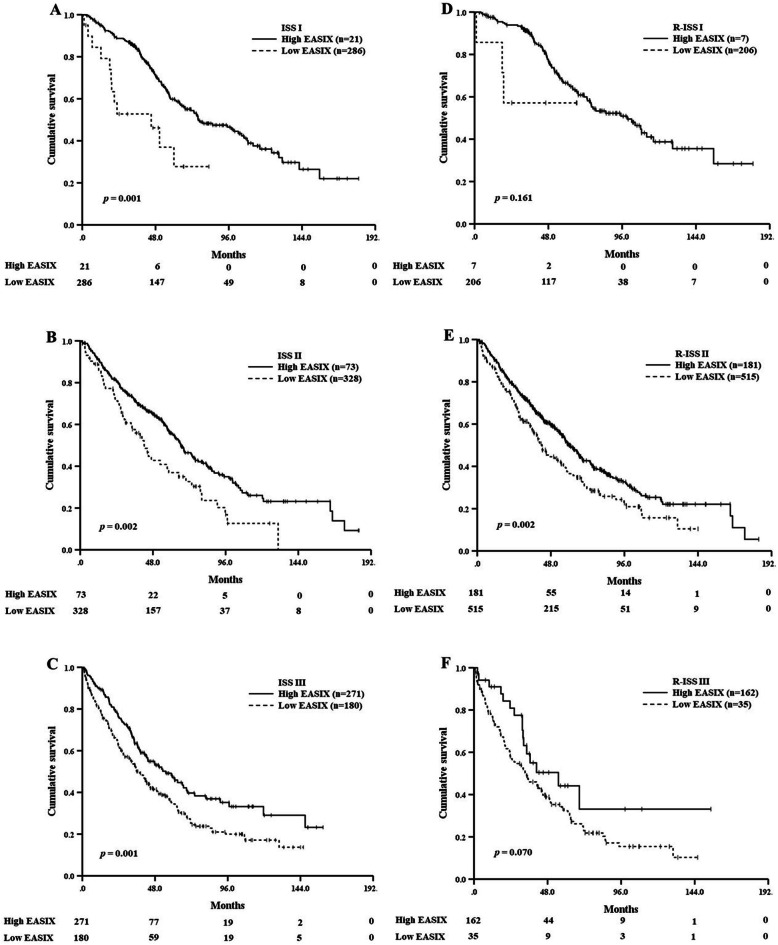

Prognostic impact of EASIX in each stage of ISS or R-ISS

This study analyzed whether EASIX could further stratify prognosis in more detail when integrated with ISS or R-ISS. In 307 patients with ISS I, 21 patients (6.8%) with high EASIX showed significantly inferior OS compared to other patients with low EASIX [45.2 months (95% CI 12.8–77.5) vs. 76.0 months (95% CI 54.7–97.3), p = 0.001, Fig. 4a]. In 401 patients with ISS II, 73 patients (18.2%) with high EASIX also showed significantly inferior OS compared to patients with low EASIX [42.3 months (95% CI 32.7–51.9) vs. 66.5 months (95% CI 58.8–74.2), p = 0.002, Fig. 4b]. In 451 patients with ISS III, 271 patients (60.1%) with high EASIX had significantly inferior OS than patients with low EASIX [36.8 months (95% CI 30.7–43.0) vs. 55.1 months (95% CI 40.2–70.0), p = 0.001, Fig. 4c]. Regarding R-ISS, OS was significantly different according to the EASIX group in R-ISS II [42.1 months (95% CI 35.5–48.8) vs. 61.0 months (95% CI 55.2–66.7), p = 0.002], but was not different in R-ISS I or R-ISS III [R-ISS I, not reached vs. 99.3 months (95% CI 72.3–126.2), p = 0.161; R-ISS III, 33.4 months (95% CI 22.3–44.5) vs. 55.1 months (95% CI 20.7–89.5), p = 0.070] (Fig. 4d, e, f).

Fig. 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for overall survival according to the Endothelial Activation and Stress Index (EASIX) score (a, b, c) in each subgroup of the International Staging System (ISS), and (d, e, f) in each subgroup of the Revised International Staging System (R-ISS)

Discussion

This study showed that EASIX is a simple and powerful predictor of survival outcome in patients with newly diagnosed MM. Although fewer patients with high EASIX received ASCT than those with low EASIX, EASIX showed a prognostic value independent of ASCT. EASIX is a simple formula that can be calculated using platelet counts, serum creatinine, and LDH. These three variables as EASIX have been reported as a prognostic factor in MM. Elevated levels of serum LDH are associated with advanced disease and inferior survival outcomes in patients with MM who were treated with effective new agents such as thalidomide, lenalidomide, or bortezomib [11, 12]. Renal insufficiency at diagnosis is also associated with advanced disease stage and high tumor burden in MM [13, 14]. In addition, patients with renal insufficiency at diagnosis showed high risk of treatment-related toxicity and early mortality [15, 16]. Although development of new, effective agents improved the renal function and reduced early mortality [17, 18], a recent registry study showed that patients with renal insufficiency still had inferior survival outcomes compared to those with normal renal function [13]. The prognostic impact of platelet counts in MM is unclear. Platelet production, regardless of the degree of bone marrow plasmacytic infiltration, is probably affected by cytokines such as megakaryocyte growth factors, which are related to MM pathogenesis [19]. Further, MM patients who present with a low platelet count at diagnosis tend to have adverse prognosis [20–22]. As described in Table 1, the patients with high EASIX have more adverse clinical characteristics like hypercalcemia, anemia, poor performance status than the patients with low EASIX. And the patients with high EASIX have a significantly higher proportion of ISS III and R-ISS III than the patients with low EASIX. These mean that EASIX score reflects tumor burden and aggressiveness. Therefore, we considered that EASIX comprising these three variables could be useful to predict survival in MM.

EASIX was originally developed as an endothelial damage-related biomarker in patients with acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Luft et al. [5] first evaluated the prognostic role of EASIX in patients with acute GVHD after allogeneic stem cell transplantation, and demonstrated that patients with high EASIX showed a significantly higher non-relapsed mortality and inferior OS compared to those with low EASIX. A recent study showed that EASIX was associated with serological endothelial stress markers, especially angiopoieitin-2, and was significantly associated with poor OS in transplant-ineligible patients with low risk myelodysplastic syndrome [6]. This study suggested that EASIX could be a broadly applicable tool to predict prognosis independently of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. In MM, endothelial dysfunction and angiogenesis are important for disease progression and have prognostic potential. Endothelial cells in MM differently express cell adhesion molecules, receptors for cytokines, and growth factors compared to resting endothelial cells and these contribute to angiogenesis, which is essential for tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis [23–25]. Angiopeietin-2, an angiogenesis marker, is increased in MM and is associated with advanced disease and inferior survival [26, 27]. Therefore, EASIX may be important for the prognostic stratification of MM as an endothelial dysfunction-related marker independent of other prognostic factors.

This study showed that EASIX is useful to predict the survival in each group of ISS. ISS is a simple risk stratification system based on serum β2-microglobulin and albumin [28]; however, there was a concern for the prognostic value of ISS with respect to the introduction of new effective agents to treat MM. R-ISS was a new prognostic stratification system proposed by the International Myeloma Working Group [4]. The R-ISS stratifies patients into homogeneous survival subgroups by classifying patients with stage I and a poor prognosis, and patients with stage III and a better prognosis into stage II. Therefore, patients with R-ISS stage I and III had more homogenous survival outcomes, whereas patients with stage II were markedly increased and had heterogeneous survival outcomes [29, 30]. In this study, no significant difference in survival was observed according to EASIX in R-ISS I or III, but patients with high EASIX scores had significantly inferior survival than those with low EASIX. Thus, EASIX may be useful to further discriminate survival outcomes in each stage of ISS, or R-ISS II.

This study has some limitations. First, we do not have any data regarding progression-free survival (PFS). The clinical significance of PFS is growing in MM as many effective salvage treatment regimens including novel drugs are developed and affect OS prolongation. Further analysis about the association between EASIX and PFS could strengthen the prognostic role of EASIX. Second, we only evaluated EASIX score at the time of initial diagnosis. Assessment of EASIX at ASCT, disease progression, or recurrence might also be useful to analyze the prognostic value of EASIX. Third, there might be some limitations in the assessment of EASIX because platelet counts, creatinine, and LDH levels could be affected by several other conditions like heart problems, liver disease, or infection. Although the frequency of cardiovascular and liver disease was similar between the high EASIX and low EASIX group, we did not accurately analyze the effect of underlying disease on EASIX. Finally, this study cohort is heterogeneous because the diagnosis year is widely distributed and patients received variable induction and salvage treatment. Also, there is a possibility of over-fitting because of the lack of validation cohorts, and therefore the prognostic role of EASIX needs to be validated in further researches.

Conclusions

This study firstly evaluated the prognostic impact of EASIX in patients with newly diagnosed MM. Patients with high EASIX at diagnosis had unfavorable characteristics, advanced disease stages, and showed significantly inferior survival outcomes compared to those with low EASIX. In addition, EASIX was useful to predict survival in each group of ISS or R-ISS II. Therefore, EASIX is a simple and powerful predictor of survival outcome in patients with newly diagnosed MM.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Univariate and multivariate Cox analysis for overall survival (n = 1,177).

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ASCT

Autologous stem cell transplantation

- CA

Chromosomal abnormalities

- EASIX

Endothelial Activation and Stress Index

- GVHD

Graft-versus-host disease

- IMids

Immunomodulatory drugs

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- MGUS

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance

- MM

Multiple myeloma

- OS

Overall survival

- PS

Performance score

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- R-ISS

Revised International Staging System

Authors’ contributions

S.H.J. K.K., and J.J.L. designed the study, G.Y.S. and S.H.J. prepared the manuscript. S.J.K., S.E.Y., H.S.L., M.K., S.Y.A., D.H.Y., J.S.A., an H.J.K. critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

There is no funding source in this study.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional ethics committee at Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital and was conducted in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki principles. The institutional ethics committee at Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital waived the requirement to obtain informed consent because of retrospective nature of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Sung-Hoon Jung, Email: shglory@hanmail.net.

Kihyun Kim, Email: kihyunkimk@gamil.com.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12885-020-07317-y.

References

- 1.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Multiple myeloma. Blood. 2008;111(6):2962–2972. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-078022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corre J, Cleynen A, Robiou du Pont S, Buisson L, Bolli N, Attal M, Munshi N, Avet-Loiseau H. Multiple myeloma clonal evolution in homogeneously treated patients. Leukemia. 2018;32(12):2636–2647. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0153-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manier S, Salem KZ, Park J, Landau DA, Getz G, Ghobrial IM. Genomic complexity of multiple myeloma and its clinical implications. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(2):100–113. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palumbo A, Avet-Loiseau H, Oliva S, Lokhorst HM, Goldschmidt H, Rosinol L, Richardson P, Caltagirone S, Lahuerta JJ, Facon T, et al. Revised international staging system for multiple myeloma: a report from international myeloma working group. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(26):2863–2869. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luft T, Benner A, Jodele S, Dandoy CE, Storb R, Gooley T, Sandmaier BM, Becker N, Radujkovic A, Dreger P, et al. EASIX in patients with acute graft-versus-host disease: a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Haematol. 2017;4(9):e414–e423. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(17)30108-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merz A, Germing U, Kobbe G, Kaivers J, Jauch A, Radujkovic A, Hummel M, Benner A, Merz M, Dreger P, et al. EASIX for prediction of survival in lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9(11):85. doi: 10.1038/s41408-019-0247-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shouval R, Fein JA, Shouval A, Danylesko I, Shem-Tov N, Zlotnik M, Yerushalmi R, Shimoni A, Nagler A. External validation and comparison of multiple prognostic scores in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 2019;3(12):1881–1890. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019032268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varma A, Rondon G, Srour SA, Chen J, Ledesma C, Champlin RE, Ciurea SO, Saliba RM. Endothelial activation and stress index (EASIX) at admission predicts fluid overload in recipients of allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biology Blood Marrow Transplantation. 2020;26(5):1013–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luft T, Benner A, Terzer T, Jodele S, Dandoy CE, Storb R, Kordelas L, Beelen D, Gooley T, Sandmaier BM, et al. EASIX and mortality after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55(3):553–561. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0703-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hothorn T, Lausen B. On the exact distribution of maximally selected rank statistics. Comput Stat Data Anal. 2003;43(2):121–137. doi: 10.1016/S0167-9473(02)00225-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maltezas D, Dimopoulos MA, Katodritou I, Repousis P, Pouli A, Terpos E, Panayiotidis P, Delimpasi S, Michalis E, Anargyrou K, et al. Re-evaluation of prognostic markers including staging, serum free light chains or their ratio and serum lactate dehydrogenase in multiple myeloma patients receiving novel agents. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31(2):96–102. doi: 10.1002/hon.2026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chim CS, Sim J, Tam S, Tse E, Lie AK, Kwong YL. LDH is an adverse prognostic factor independent of ISS in transplant-eligible myeloma patients receiving bortezomib-based induction regimens. Eur J Haematol. 2015;94(4):330–335. doi: 10.1111/ejh.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ho PJ, Moore EM, McQuilten ZK, Wellard C, Bergin K, Augustson B, Blacklock H, Harrison SJ, Horvath N, King T, et al. Renal impairment at diagnosis in myeloma: patient characteristics, treatment, and impact on outcomes. Results from the Australia and New Zealand myeloma and related diseases registry. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2019;19(8):e415–e424. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2019.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimopoulos MA, Terpos E, Chanan-Khan A, Leung N, Ludwig H, Jagannath S, Niesvizky R, Giralt S, Fermand JP, Blade J, et al. Renal impairment in patients with multiple myeloma: a consensus statement on behalf of the international myeloma working group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(33):4976–4984. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Torra R, Blade J, Cases A, Lopez-Pedret J, Montserrat E, Rozman C, Revert L. Patients with multiple myeloma requiring long-term dialysis: presenting features, response to therapy, and outcome in a series of 20 cases. Br J Haematol. 1995;91(4):854–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Augustson BM, Begum G, Dunn JA, Barth NJ, Davies F, Morgan G, Behrens J, Smith A, Child JA, Drayson MT. Early mortality after diagnosis of multiple myeloma: analysis of patients entered onto the United Kingdom Medical Research Council trials between 1980 and 2002--Medical Research Council adult Leukaemia working party. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9219–9226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimopoulos MA, Roussou M, Gkotzamanidou M, Nikitas N, Psimenou E, Mparmparoussi D, Matsouka C, Spyropoulou-Vlachou M, Terpos E, Kastritis E. The role of novel agents on the reversibility of renal impairment in newly diagnosed symptomatic patients with multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2013;27(2):423–429. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dimopoulos MA, Delimpasi S, Katodritou E, Vassou A, Kyrtsonis MC, Repousis P, Kartasis Z, Parcharidou A, Michael M, Michalis E, et al. Significant improvement in the survival of patients with multiple myeloma presenting with severe renal impairment after the introduction of novel agents. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(1):195–200. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozkurt ZN, Yagci M, Sucak GT, Kirazli S, Haznedar R. Thrombopoietic cytokines and platelet count in multiple myeloma. Platelets. 2010;21(1):33–36. doi: 10.3109/09537100903360007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kyle RA, Gertz MA, Witzig TE, Lust JA, Lacy MQ, Dispenzieri A, Fonseca R, Rajkumar SV, Offord JR, Larson DR, et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(1):21–33. doi: 10.4065/78.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eleftherakis-Papapiakovou E, Kastritis E, Roussou M, Gkotzamanidou M, Grapsa I, Psimenou E, Nikitas N, Terpos E, Dimopoulos MA. Renal impairment is not an independent adverse prognostic factor in patients with multiple myeloma treated upfront with novel agent-based regimens. Leuk Lymphoma. 2011;52(12):2299–2303. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.597906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavo M, Galieni P, Zuffa E, Baccarani M, Gobbi M, Tura S. Prognostic variables and clinical staging in multiple myeloma. Blood. 1989;74(5):1774–1780. doi: 10.1182/blood.V74.5.1774.1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vacca A, Ria R, Semeraro F, Merchionne F, Coluccia M, Boccarelli A, Scavelli C, Nico B, Gernone A, Battelli F, et al. Endothelial cells in the bone marrow of patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2003;102(9):3340–3348. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vacca A, Ribatti D. Bone marrow angiogenesis in multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20(2):193–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Manier S, Sacco A, Leleu X, Ghobrial IM, Roccaro AM. Bone marrow microenvironment in multiple myeloma progression. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:157496. doi: 10.1155/2012/157496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terpos E, Anargyrou K, Katodritou E, Kastritis E, Papatheodorou A, Christoulas D, Pouli A, Michalis E, Delimpasi S, Gkotzamanidou M, et al. Circulating angiopoietin-1 to angiopoietin-2 ratio is an independent prognostic factor for survival in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma who received therapy with novel antimyeloma agents. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(3):735–742. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pappa CA, Alexandrakis MG, Boula A, Thanasia A, Konsolas I, Alegakis A, Tsirakis G. Prognostic impact of angiopoietin-2 in multiple myeloma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2014;140(10):1801–1805. doi: 10.1007/s00432-014-1731-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greipp PR, San Miguel J, Durie BG, Crowley JJ, Barlogie B, Blade J, Boccadoro M, Child JA, Avet-Loiseau H, Kyle RA, et al. International staging system for multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3412–3420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jung SH, Kim K, Kim JS, Kim SJ, Cheong JW, Kim SJ, Ahn JS, Ahn SY, Yang DH, Kim HJ, et al. A prognostic scoring system for patients with multiple myeloma classified as stage II with the revised international staging system. Br J Haematol. 2018;181(5):707–710. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gonzalez-Calle V, Slack A, Keane N, Luft S, Pearce KE, Ketterling RP, Jain T, Chirackal S, Reeder C, Mikhael J, et al. Evaluation of revised international staging system (R-ISS) for transplant-eligible multiple myeloma patients. Ann Hematol. 2018;97(8):1453–1462. doi: 10.1007/s00277-018-3316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Table 1. Univariate and multivariate Cox analysis for overall survival (n = 1,177).

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used and analyzed during this study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.