Abstract

Purpose

To assess the efficacy and safety of recombinant human endostatin in combination with radiotherapy (RT) or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (LA-NSCLC).

Methods

We searched eligible literature in available databases using combinations of the following search terms: lung cancer, endostatin or endostar, radiotherapy or radiation therapy or chemoradiotherapy. The inclusion criteria were: prospective or retrospective (including single-arm) studies that evaluated the efficacy and safety of endostatin plus radiotherapy (ERT) or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (ECRT) in patients with LA-NSCLC. Primary outcomes included the following: objective response rate (ORR), local control rates (LCR), overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and adverse events (AEs). Tests of heterogeneity, sensitivity, and publication bias were performed.

Results

A total of 271 patients with LA-NSCLC from 7 studies were enrolled, including six prospective trials and one retrospective study. The pooled median PFS was 11.3 months overall, 11.2 months in the ECRT group, and 11.8 months in the ERT group. Pooled median OS and ORR were 18.9 months and 77.2% overall, 18.4 months and 77.5% in the ECRT group, and 19.6 months and 76.1% in the ERT group, respectively. The incidences of major grade ≥ 3 AEs for all patients, subgroups of ECRT and ERT were 10.9% vs 11.9% vs 9.4% for radiation pneumonitis, 11.6% vs 12.2% vs 9.4% for radiation esophagitis, 35.5% vs 43.4% vs 0 for leukopenia, 27.8% vs 40.7% vs 2.1% for neutropenia, and 10.5% vs 12.3% vs 2.1% for anemia.

Conclusions

Combined endostatin with RT or CCRT is effective and well tolerated in treating LA-NSCLC, and less toxicities occur. Further validation through prospective randomized control trials is required.

Keywords: Chemoradiotherapy, Endostatin, Non-small cell lung cancer, Radiotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cancer type worldwide [1], and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common form (80–85%) [2]. At the time of initial diagnosis, approximately one-third of patients with NSCLC present with locally advanced NSCLC (LA-NSCLC) [3]. Furthermore, about 70% of LA-NSCLCs are unresectable, and chemoradiotherapy (CRT) was the recommended standard care for these patients [4, 5]. No significant progress in the treatment of LA-NSCLC was made for many years until the PACIFIC study confirmed that consolidation therapy with durvalumab (a monoclonal antibody that blocks interactions of programmed cell death ligand 1 with the PD-1 receptor) further improved survival following CRT [6–8].

Previous studies indicated that a hypoxic tumor microenvironment contributes not only to resistance of tumor cells to chemoradiation but also promotes metastasis [9, 10], and tumor oxygenation is essential for effective application of radiotherapy (RT) or CRT [11]. Therefore, novel treatments that enhance radiosensitivity by improving the hypoxic microenvironment are urgently needed. Prior to the findings of the PACIFIC study, researchers explored whether patients with LA-NSCLC could benefit from anti-angiogenic drugs combined with RT or CRT. However, earlier studies showed that administration of bevacizumab along with thoracic RT led to a high incidence of pulmonary toxicity, including radiation pneumonitis, hemoptysis and tracheoesophageal fistulae, in patients with stage III NSCLC [12, 13]. Therefore, concurrent bevacizumab with thoracic RT is unlikely to be further pursued as a treatment option for stage III NSCLC.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that endostatin (a broad-spectrum angiogenesis inhibitor) is able to normalize tumor vasculature, alleviate hypoxia and increase tumor sensitivity to radiation [14, 15]. Several studies have indicated enhanced efficacy and tolerable toxicity of endostatin combined with thoracic RT or CRT for patients with LA-NSCLC [16–18]. However, the reported studies to date are mostly retrospective or single arm studies with limited patient enrolment. In the present study, we performed a pooled analysis to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of endostatin combined with RT or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in patients with LA-NSCLC.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic search for available articles, both in published and abstract forms of PubMed, OVID, Web of SCI, EMBASE, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang databases. The final literature search was performed on June 30, 2019, using the following search terms: “lung cancer” AND (endostatin OR endostar) AND (radiotherapy OR radiation therapy OR chemoradiotherapy). Manual updates of abstracts presented till the 2019 meetings, such as American Society of Clinical Oncology, European Society for Medical Oncology, World Conference of Lung Cancer, and American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology were additionally performed.

Study selection and search strategy

Studies that met the following inclusion criteria were included in the pooled analysis: 1) prospective or retrospective (including single-arm) studies that evaluated the efficacy and safety of endostatin plus radiotherapy (ERT) or concurrent chemoradiotherapy (ECRT) in patients with LA-NSCLC; 2) studies with primary outcomes reporting at least one of the following endpoints: objective response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS), and local control rates (LCR), or adverse events (AEs) based on Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0 or 4.0; 3) number of cases included for study was ≥10; 4) articles or abstracts were written in English. After the selection process, the remaining titles and abstracts were screened for relevance independently by two authors. Full-text articles and meeting abstracts were finally reviewed for all studies that met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers according to the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by discussing with a third reviewer. Each reviewer extracted data including author name, the publication years of the studies, number of patients, patient characteristics, treatment regimen, radiotherapy dosage, the method of endostatin administration, ORR, PFS, OS, LCR and AEs. The Jadad scale [19] and Newcastle Ottawa Scale [20] were used to assess the quality of the included studies.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (version 3.0) software (Biostat Inc., NJ, USA). For dichotomous variables, such as OS rates, PFS rates, ORR, LCR and AEs, we calculated the raw proportion of events divided by the total number of clinically evaluable patients. Additionally, we calculated weighted pooled rates of events by the number of clinically evaluable patients using a random effects model to account for heterogeneity in study size and the large variations in proportion. Median pooled weighted OS and PFS were calculated with descriptive statistics. Subgroup analysis was performed per type of treatment regimen (ERT or ECRT).

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

The potential for publication bias in reported ORR values was assessed by funnel plots, with the appropriate accuracy intervals. Sensitivity analyses were performed for the results for ORR based on the leave-one-out approach.

Results

Literature search

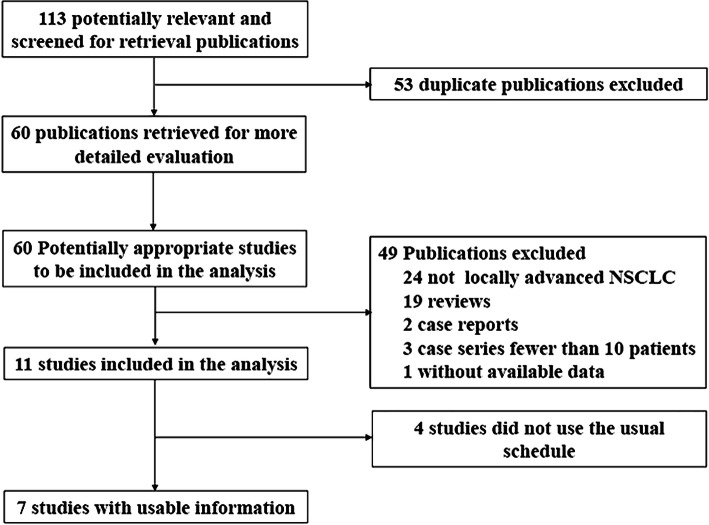

Figure 1 depicts a flowchart of the literature search procedure. Overall, 113 records were identified using the search strategy and 102 records excluded after screening the titles and abstracts. Among the remaining 11 potentially relevant studies, four were excluded due to endostatin administration via arterial infusion or discontinuation of endostatin in the first cycle during RT. Finally, seven studies [16, 18, 21–25] involving 271 patients were pooled for analysis.

Fig. 1.

Overview of study search and selection

Included studies and patient characteristics

The characteristics of the selected studies are summarized in Table 1. The included studies comprised three prospective cohort studies, three single-arm prospective studies and one single-arm retrospective study. Follow-up data were available for five studies, with a median follow-up period between 20.0 and 37.1 months. In total, 212 evaluable patients in four studies received endostatin combined with CCRT (ECRT) and 59 evaluable patients in three studies received endostatin combined with single RT (ERT). Patients received a total dose of 60–68 Gy in 30–34 fractions for 6–7 weeks. However, the methods of endostatin treatment differed among studies, including continuous intravenous pumping (CIV) of endostatin (7.5 mg/m2/day) over 5 days, administration of endostatin (7.5 mg/m2/day) over 4 h for 7 days at weeks 1, 3, 5, and 7 or via an endostatin intravenous drip (IV) (15 mg/day) for 14 days per 3 weeks, etc. Almost all included patients had unresectable LA-NSCLC at the time of study entry. The median patient age ranged from 56 to 76 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Published year | Study type | No. of cases | Endpoints | Treatment regimen | Radiation dose (Gy) | Endostatin usage | Total duration of endostatin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jiang [16] | 2012 | Prospective cohort study | 25 | 1-, 2-yr OS rate, 1-, 2-yr LCR, OS, ORR, AEs | ERT | 60 | 15 mg/day IV for 7 days during the first week of RT | 7 days× 1 cycles |

| Zhai [18] | 2019 | Single-arm prospective study | 67 | 1-, 2-, 3-yr PFS/OS rate, PFS,OS, ORR, AEs | ECRT | 60–66 | 7.5 mg/m2/day CIV for 5 days before the beginning of RT, and then repeated at week 2, 4, and 6 during RT | 5 days× 4 cycles |

| Sun [21] | 2016 | Single-arm prospective study | 19 | ORR, PFS, OS, AEs | ECRT | 60–66 | 7.5 mg/m2/day IV for 14 days per 3 weeks during RT | 14 days× 2 cycles |

| Bao [22] | 2015 | Single-arm prospective study | 48 | OS, 1-, 2-, 3-yr PFS/OS rate and LCR, PFS, ORR, AEs | ECRT | 60–66 | 7.5 mg/m2/day IV for 7 days before the beginning of RT, and then repeated at week 2, 4, and 6 during RT | 7 day× 4 cycles |

| Tang [23] | 2016 | Single-arm retrospective study | 78 | PFS, OS, ORR | ECRT | 60–66 | 7.5 mg/m2/day IV over 4 h per day for 7 days, or CIV for 5 days, at week 1, 3, 5 and 7, endostatin administrated 1 week prior to CRT | 5/7 days× 4 cycles |

| Wen [24] | 2009 | Prospective cohort study | 14 | ORR, PFS, 1-yr OS rate | ERT | 66–68 | 15 mg/day IV during the first three weeks of RT | 21 days× 1 cycles |

| Chen [25] | 2017 | Prospective cohort study | 20 | ORR, PFS, OS, AEs | ERT | 60–66 | 15 mg/day IV for 14 days per three weeks during RT | 14 day×2 cycles |

OS Overall survival, PFS Progression-free survival, ORR Objective response rate, LCR Local control rate, AEs Adverse events, ERT Endostatin combined with radiotherapy, ECRT Endostatin combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, yr Year, RT Radiotherapy, IV Intravenous injection, CIV Continuous intravenous pumping

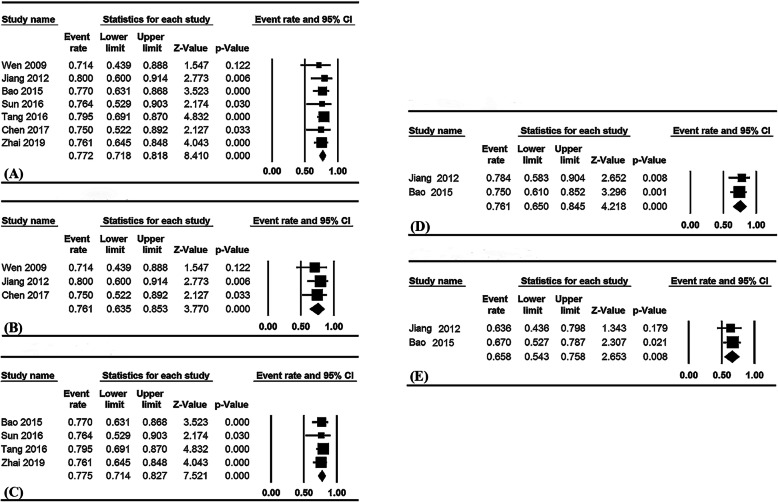

Pooled ORR and LCR

Pooled ORR and LCR data are summarized in Table 2. The pooled overall ORR for the seven studies was 77.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 71.8–81.8%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 2a), 76.1% (95% CI, 63.5–85.3%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 2b) in the ERT group and 77.5% (95% CI, 71.4–82.7%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 2c) in the ECRT group. Higher ORR was observed in the ERT group, compared with the RT alone group (76.1% vs 61.7%, respectively).

Table 2.

Pooled efficacy of endostatin combined with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy

| Endpoints | Group | No. of studies | No. of cases | Weighted pooled data (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate | ||||

| ORR (%) | Overall | 7 | 271 | 77.2 (71.8–81.8) |

| ECRT | 4 | 212 | 77.5 (71.4–82.7) | |

| ERT | 3 | 59 | 76.1 (63.5–85.3) | |

| 1-yr LCR (%) | Overall | 2 | 73 | 76.1 (65.0–84.0) |

| 2-yr LCR (%) | Overall | 2 | 73 | 65.8 (54.3–75.8) |

| Progression-free survival | ||||

| Median PFS (months) | Overall | 6 | 246 | 11.3 |

| ECRT | 4 | 212 | 11.2 | |

| ERT | 2 | 34 | 11.8 | |

| 1-yr PFS rate (%) | ECRT | 2 | 115 | 49.6 (40.5–58.6) |

| 2-yr PFS rate (%) | ECRT | 2 | 115 | 31.7 (23.8–40.8) |

| 3-yr PFS rate (%) | ECRT | 2 | 115 | 23.7 (16.7–32.5) |

| Overall survival | ||||

| Median OS (months) | Overall | 4 | 142 | 18.9 (15.3–22.5) |

| ECRT | 2 | 97 | 18.4 (9.7–27.0) | |

| ERT | 2 | 45 | 19.6 (16.2–23.1) | |

| 1-yr OS rate (%) | Overall | 4 | 154 | 79.4 (72.1–85.1) |

| ECRT | 2 | 115 | 81.6 (73.5–87.7) | |

| ERT | 2 | 39 | 72.8 (55.9–85.0) | |

| 2-yr OS rate (%) | Overall | 3 | 140 | 59.0 (49.7–67.8) |

| 3-yr OS rate (%) | ECRT | 2 | 115 | 55.7 (45.6–65.6) |

| ECRT | 2 | 115 | 43.9 (29.8–59.0) | |

OS Overall survival, PFS Progression-free survival, ORR Objective response rate, LCR Local control rate, ERT Endostatin combined with radiotherapy, ECRT Endostatin combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, yr Year

Fig. 2.

Pooled ORR for all patients (a), ERT (b) and ECRT (c) groups; pooled LCR for all patients, 1-year LCR (d) and 2-year LCR (e). ORR: objective response rates; ERT: endostatin combined with radiotherapy alone; ECRT: endostatin combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy; LCR: local control rates

Only two studies in which the treatment regimens were ECRT and ERT reported LCR data. The pooled 1- and 2-year LCR rates were 76.1% (95% CI, 65.0–84.0%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 2d) and 65.8% (95% CI, 54.3–75.8%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 2e), respectively.

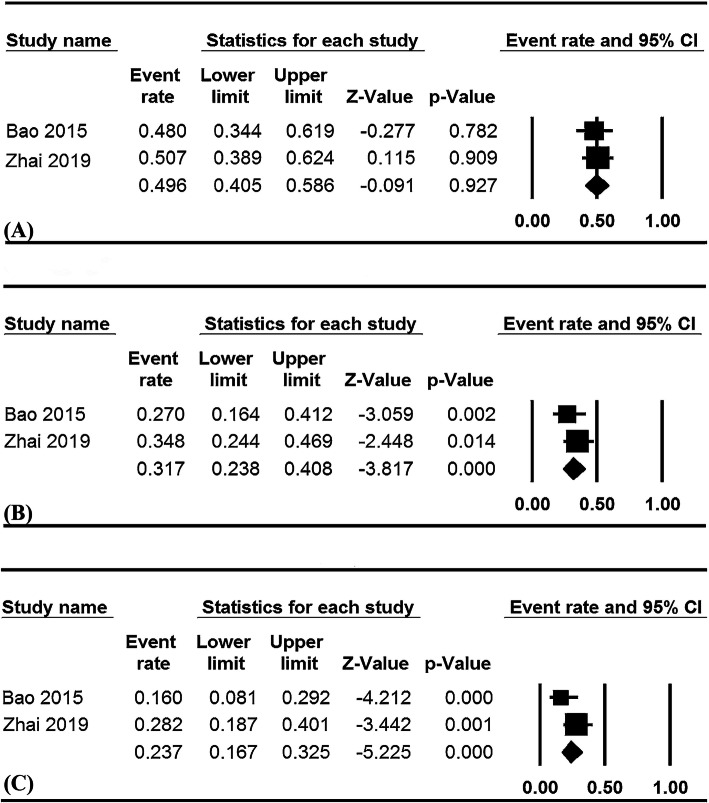

Pooled survival

The pooled survival data are summarized in Table 2. Only two studies in ECRT group reported PFS rates. The pooled 1-, 2- and 3-year PFS rates were 49.6% (95% CI, 40.5–58.6%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 3a), 31.7% (95% CI, 23.8–40.8%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 3b), and 23.7% (95% CI, 16.7–32.5%; I2 = 56.3%, Fig. 3c), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Pooled PFS rates for ECRT group, 1-year (a), 2-year (b), and 3-year PFS rates (c). PFS: progression-free survival; ECRT: endostatin combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy

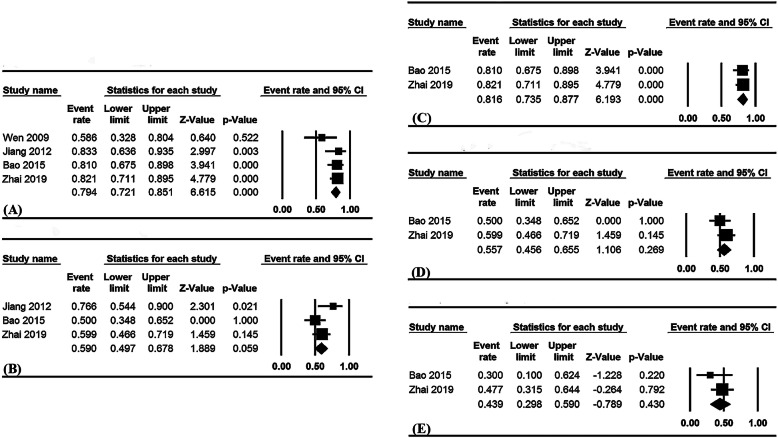

Four studies documented the 1-year OS rate, three the 2-year OS rate, and two the 3- year OS rate. The overall pooled 1- and 2-year OS rates were 79.4% (95% CI, 72.1–85.1%; I2 = 25.2%, Fig. 4a) and 59.0% (95% CI, 49.7–67.8%; I2 = 48.1%, Fig. 4b), respectively. Based on stratification by treatment regimens, the pooled 1-, 2- and 3-year OS rates in the ECRT group were 81.6% (95% CI, 73.5–87.7%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 4c), 55.7% (95% CI, 45.6–65.6%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 4d) and 43.9% (95% CI, 29.8–59.0%; I2 = 0%, Fig. 4e); the pooled 1-year OS rate in the ERT group was 72.8% (95% CI, 55.9–85.0%; I2 = 63.3%).

Fig. 4.

Pooled 1-year (a) and 2-year OS rates (b) for overall patients; pooled OS rates for the ECRT group, 1-year (c), 2-year (d), and 3-year (e) OS rate. OS: overall survival; ECRT: endostatin combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy

Six of the included studies had recorded median PFS values. Patients received ECRT in four of these studies and ERT in the remaining two studies, with only three of the above studies recording both the PFS value and 95% CI. Accordingly, pooled median PFS was calculated by a weighted average of the single study median [26]. The pooled median PFS was recorded as 11.3 months overall, 11.2 months in the ECRT group, and 11.8 months in the ERT group.

OS data and 95% CI were reported in four studies. The overall pooled median OS was 18.9 months (95% CI, 15.3–22.5, I2 = 87.6%), 18.4 months (95% CI, 9.7–27.0, I2 = 92.6%) in the ECRT group and 19.6 months (95% CI, 16.2–23.1, I2 = 78.7%) in the ERT group.

Safety

The most common AEs documented in the five selected studies, including 179 patients, were radiation pneumonitis, radiation esophagitis, thrombocytopenia, and anemia. Additionally, nausea/vomiting, neutropenia and leukopenia were three commonly observed AEs in three of the above four studies. Pooled data on AEs are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pooled adverse events of endostatin combined with radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy

| Events | Grade | Incidence, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | ECRT group | ERT group | ||

| Radiation pneumonitis | All | 55.9 (31.4–77.9) | 50.7 (20.9–80.0) | 64.1 (27.3–89.4) |

| ≥3 | 10.9 (5.4–20.8) | 11.9 (4.5–27.9) | 9.4 (3.3–24.0) | |

| Radiation esophagitis | All | 77.4 (69.4–83.7) | 89.7 (83.1–93.9) | 55.5 (40.9–69.3) |

| ≥3 | 11.6 (7.6–17.5) | 12.2 (7.6–19.0) | 9.4 (3.3–24.0) | |

| Neutropenia | All | 76.5 (55.6–89.4) | 85.7 (78.5–90.7) | 25.1 (71.6–89.9) |

| ≥3 | 27.8 (14.3–47.0) | 40.1 (30.3–50.8) | 2.1 (0.3–13.7) | |

| Leukopenia | All | 84.5 (49.7–96.8) | 91.8 (78.2–97.2) | 40 |

| ≥3 | 35.5 (18.5–57.7) | 43.4 (27.2–61.2) | 0 | |

| Anemia | All | 54.7 (34.7–73.3) | 70.5 (62.1–77.6) | 28.9 (17.6–43.6) |

| ≥3 | 10.5 (6.2–17.2) | 12.3 (7.6–19.1) | 2.1 (0.3–13.7) | |

| Thrombocytopenia | All | 46.0 (23.2–59.3) | 52.5 (34.2–70.2) | 35.7 (23.1–50.7) |

| ≥3 | 6.9 (2.4–18.3) | 10.1 (3.3–26.7) | 2.1 (0.3–13.7) | |

| Nausea/vomiting | All | 48.2 (32.5–64.2) | 54.1 (38.7–68.7) | 40 |

| ≥3 | 5.8 (2.8–11.6) | 6.3 (3.0–12.9) | 0 | |

| Arrhythmia | All | 25.7 (9.5–52.7) | 37 | 15 |

| ≥3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Fatigue | All | 58.0 (39.3–74.7) | 67.4 (56.7–76.5) | 40 |

| ≥3 | 2.6 (0.7–8.7) | 2.7 (0.7–1.3) | 0 | |

| Hemorrhage | All | NR | 15.2 (9.0–24.5) | NR |

| ≥3 | NR | 1.8 (0.4–8.3) | NR | |

| Hypertension | All | NR | 2 | NR |

| ≥3 | NR | 0 | NR | |

ERT Endostatin combined with radiotherapy, ECRT Endostatin combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy, NR Not reported

Radiation pneumonitis and esophagitis

The pooled frequencies of any grade and grade ≥ 3 radiation pneumonitis were 55.9 and 10.9% overall, 50.7 and 11.9% in the ECRT group, and 64.1 and 9.4% in the ERT group, respectively. The pooled frequencies of any grade and grade ≥ 3 radiation esophagitis were 77.4 and 11.6% overall, 89.7 and 12.2% in the ECRT group, and 55.5 and 9.4% in the ERT group, respectively.

Hematological toxicity

More than 10% of grade ≥ 3 hematological toxicities in all patients were neutropenia, leukopenia, and anemia, with incidences of 27.8, 35.5, and 10.5%, respectively. The pooled rates were 40.1% vs 2.1, 43.4% vs 0, and 12.3% vs 2.1%, respectively, in the ECRT and ERT groups. Rates of thrombocytopenia of grade ≥ 3 were 6.9, 10.1 and 2.1% for all patients, ECRT and ERT groups, respectively.

Other toxicities

Several other toxicities, including nausea, arrhythmia, fatigue, hemorrhage, and hypertension were additionally reported (Table 3). All of above AEs incidences of grade ≥ 3 were less than 10% for either all patients or for any of subgroups. Only one study reported AE of hypertension, in which patients received ECRT, with a frequency of 2% in any grade, and 0% in grade ≥ 3, respectively.

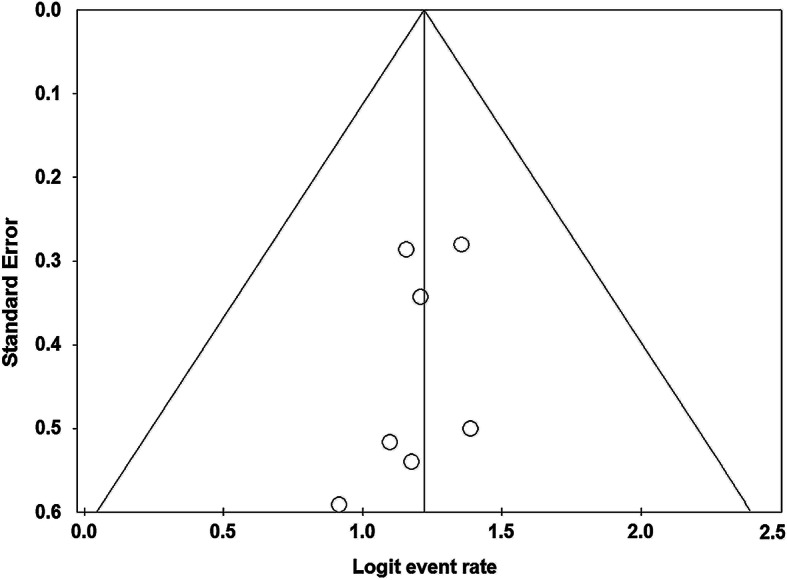

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Publication bias was assessed for ORR according to Begg’s test and no significant publication bias was observed (Fig. 5). Besides, results of sensitivity analysis by omitting one study at a time did not substantially change the overall results.

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot of publication bias for ORR. ORR: objective response rates

Discussion

CRT plus consolidation durvalumab is now considered standard of care for inoperable stage III NSCLC, but the optimal treatment strategies for the sequence and combination of CRT, immunotherapy, and even anti-angiogenic therapy are still being studied. Although data from prospective phase III randomized control studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of endostatin combined with RT or CCRT for patients with LA-NSCLC are lacking, our pooled analysis indicates that endostatin combined with CCRT or RT presents a promising treatment modality in treatment of LA-NSCLC; subgroups of ECRT and ERT have similar efficacy and survival benefit, but patients in the ERT subgroup had lower rates of toxicity.

Since tumor angiogenesis has been identified as a critical step in growth and metastasis of malignant solid tumors, anti-angiogenesis strategies have become established as an effective therapeutic approach [27–29]. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a specific and potent angiogenic factor, contributes to the development of solid tumors by promoting angiogenesis. Several anti-VEGF or anti-VEGF-receptor (VEGFR) strategies have been developed to date, including neutralizing antibodies to VEGF/VEGFR, soluble VEGFR/VEGFR hybrids, and receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors [30–32]. Chemotherapy combined with anti-angiogenic drugs [33–35], including bevacizumab (a VEGF-A monoclonal antibody), recombinant human endostatin, and ramucirumab (a VEGFR monoclonal antibody), has led to significantly prolonged survival, compared with chemotherapy alone, and is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and/or China FDA for first- or second-line treatment of advanced NSCLC.

Solid tumors generally have characteristics of hypoxia and exhibit resistance to radiation to some extent, leading to failure of local control. Therefore, attempts to increase the sensitivity of RT via tumor oxygen enrichment present a novel direction for research [36, 37]. One of the most common factors causing hypoxia is inadequate vascular supply of the tumor, and thus sufficient blood vessel supply in the tumor microenvironment may be essential to improve the tumor radiation response for patients treated via RT [38]. Recombinant human endostatin is an endogenous broad-spectrum angiogenesis inhibitor produced by proteolytic cleavage of collagen XVIII that is suggested to interfere with the pro-angiogenic action of growth factors, such as basic fibroblast growth factor and VEGF. Preclinical studies have shown that recombinant human endostatin could transiently “normalize” the tumor vasculature to enhance efficiency of oxygen delivery and sensitivity to radiation treatment [39, 40]. Our pooled data indicate that combination of endostatin and RT with or without chemotherapy leads to better response rate, local control rate, and survival, demonstrating superior short- and long-term survival benefits, which are not inferior to the results of previous randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of CCRT (summarized in Table 4) [5, 41–44].

Table 4.

The efficacy of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in previously reported phase II/III randomized controlled trials

| Study | Number | CRT regimen | mPFS | PFS rate (%) | mOS | OS rate (%) | ORR | LCR (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (months) | 1-yr | 2-yr | (months) | 1-yr | 2-yr | (%) | 1-yr | 2-yr | Overall | |||

| RTOG 9410 [5] | 195 | RT + VP | NR | NR | NR | 17 | 61.5 | 37.4 | 70.0 | NR | NR | 70 |

| 187 | RT + EP | NR | NR | NR | 15.6 | 60.9 | 31.6 | 65.0 | NR | NR | 71 | |

| RTOG 0617 [41] | 151 | LDR + PC | 11.8 | 49.2 | 29.1 | 28.7 | 80.0 | 57.6 | NR | 83.7 | 69.3 | NR |

| 107 | HDR + PC | 9.8 | 41.2 | 21.4 | 20.3 | 69.8 | 44.6 | NR | 75.2 | 61.4 | NR | |

| 137 | LDR + PC + Cet | 10.8 | 44.3 | 24.2 | 25 | 76.2 | 56.3 | NR | 77.8 | 61.8 | NR | |

| 100 | HDR + PC + Cet | 10.7 | 46.3 | 27.5 | 24 | 71.1 | 50.1 | NR | 82.4 | 69.3 | NR | |

| PROCLAIM [42] | 283 | RT + PP | 14.1 | NR | NR | 26.8 | 76.0 | 52.0 | 35.9 | NR | NR | 62.7 |

| 272 | RT + EP | 9.8 | NR | NR | 25 | 77.0 | 52.0 | 33.0 | NR | NR | 54.2 | |

| CAMS [43] | 95 | RT + EP | 14 | 56.8 | 29.5 | 23.3 | 74.1 | 48.4 | 73.7 | NR | NR | NR |

| 96 | RT + PC | 12 | 50 | 17.7 | 20.7 | 80.2 | 43.8 | 64.6 | NR | NR | NR | |

| WJOG5008L [44] | 54 | RT + SP | 14.8 | 55.6 | 29.6 | 40.9 | 87.0 | 75.6 | 76.9 | NR | 51 | NR |

| 54 | RT + VP | 12.3 | 53.7 | 18.5 | 39 | 87.0 | 68.5 | 80.8 | NR | 28 | NR | |

CRT Chemoradiotherapy, RT Radiotherapy, LDR Low dose radiation, HDR High dose radiation, VP Vinblastine plus cisplatin, EP Etoposide plus cisplatin, PC Paclitaxel plus carboplatin, Cet Cetuximab, PP Pemetrexed plus cisplatin, SP S1 plus cisplatin, NR Not reported, PFS Progression-free survival, mPFS Median progression-free survival, OS Overall survival, mOS Median overall survival, ORR Objective response rate, LCR Local control rate, yr Year

Although RTOG 0617 trial showed a superior median OS of 28.7 months, 69% patients in this study had stage IIIA disease [41]. In contrast, more than 50% patients in our pooled analysis had stage IIIB disease, which may be one of the factors contributing to survival differences. In a phase II trial involving 83% unresectable stage IIIB patients, endostatin combined with CCRT resulted in a median OS of 24 months [22]. In each of the RCTs listed in Table 4, over 50% of patients had a performance status (PS) score of 0; however, in our pooled analysis, only 28.5% of patients had a PS score of 0. In a phase II trial involving only 13.4% of patients with a PS score of 0, endostatin combined with CCRT resulted in median PFS and OS of 13.3 months and 34.7 months, respectively [18].

Recently, the PACIFIC study conducted in patients with unresectable stage III NSCLC showed a significant survival advantage with durvalumab consolidation therapy after CCRT [8], achieving a 3-year OS rate of 57% in the durvalumab group versus 43.5% in the control group. Based on this study, National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines have recommended this regimen as standard treatment for unresectable stage III NSCLC [45]. However, the optimal sequence and combination of CRT/RT and immunotherapy are being studied. Results from several phase II trials, such as the DETERRED and ETOP NICOLAS studies, have indicated that concurrent CRT with checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) (atezolizumab/nivolumab) for the treatment of advanced NSCLC might be feasible and has no significant added toxicities over historical rates [46, 47]. Currently, many ongoing phase II/III clinical trials, such as PACIFIC2 (NCT03519971), KEYNOTE-799 (NCT03631784), EA5181 (NCT04092283), CheckMate73L (NCT04026412), etc., are evaluating the optimal treatment strategies of immunotherapy–radiotherapy combinations.

Although CCRT plays an indispensable role in the treatment of unresectable stage III NSCLC, some patients, especially the elderly or those with poor performance status who cannot tolerate toxicity induced by chemotherapy, have to receive sequential CRT or even RT alone [4, 5, 48]. Our pooled analysis indicated that patients treated with endostatin in combination with RT alone have comparable PFS (11.8 vs 11.2 months), OS (19.6 vs18.4 months), and ORR (76.1% vs 77.5%) to those administered endostatin with CCRT. In addition, pooled ORR data from the three prospective cohort studies showed that patients subjected to endostatin combined with RT had higher ORR (76.1% vs 61.7%), compared with the RT alone patient group. Therefore, combination therapy of RT and endostatin may be a promising strategy for LA-NSCLC patients with poor PS who cannot tolerate chemotherapy.

Of note, the duration and intervals of endostatin and radiotherapy combinations differed in clinical trials and may affect the outcomes (as shown in Table 1). Results from preclinical studies showed that endostatin treatment could transiently normalize the tumor vasculature by reducing microvessel density and increasing pericytic coverage of the vessel endothelium, thereby providing a time window (about 1 week) to enhance the sensitivity to RT; thus, RT delivery in this period resulted in maximal anti-tumor outcomes [15, 49]. CT perfusion imaging and hypoxia imaging suggested that the “time window” was within about 1 week after administration, during which endostatin improved blood perfusion and decreased hypoxia of lung cancer [14]. These studies provide an important experimental basis for combining endostatin with radiotherapy within the time window of 7 days (range, 5–10) after endostatin administration. In addition, given the short half-life of endostatin in vivo, CIV is considered a better delivery route to maintain a steady concentration and may improve its efficacy [49–51]. A recent study [52] which compared the outcomes of two phase II trials that involved different administration routes of endostatin combined with CCRT showed that endostatin at 7.5 mg/m2/24 h CIV for 5 days achieved higher 3- and 5-year OS rates (50.3, 41%) and safety than endostatin at 7.5 mg/m2/day IV for 7 days. Therefore, administration of 7.5 mg/m2/24h CIV for 5 days per 2 weeks, from 1 week pre-RT to the end of RT, could be a preferred scheme, on the basis of the current studies. However, the optimal duration and intervals of endostatin administration require further investigation.

In our pooled analysis, we observed that grade ≥ 3 AEs in the ECRT group were similar to those caused by CCRT reported previously (summarized in Table 5), indicating that addition of endostatin to CCRT did not obviously increase the main AEs. The pooled incidences of grade ≥ 3 radiation pneumonitis and radiation esophagitis were 10.9 and 11.6%, respectively, analogous to previous findings. Importantly, compared with the ECRT group, significantly lower rates of grade ≥ 3 AEs were observed in the ERT group, such as radiation pneumonitis (9.4% vs 11.9%), radiation esophagitis (9.4% vs 12.2%), nausea/vomiting (0% vs 6.3%), thrombocytopenia (2.1% vs 10.1%), neutropenia (2.1% vs 40.1%), anemia (2.1% vs 12.3%), and leukopenia (0% vs 43.4%).

Table 5.

Adverse events of concurrent chemoradiotherapy in previously reported phase II/III randomized controlled trials

| Study | CRT regimen | Leukopenia (%) | Neutropenia (%) | Thrombocytopenia (%) | Anemia (%) | Radiation pneumonitis (%) | Radiation esophagitis (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | ||

| RTOG 9410 [5] | RT + VP | NR | 83.9 | NR | NR | NR | 9.3 | NR | 11.8 | NR | 12.5 | NR | 22.2 |

| RT + EP | NR | 68.4 | NR | NR | NR | 16.0 | NR | 18.8 | NR | 16.9 | NR | 44.9 | |

| RTOG 0617 [41] | LDR + PC | 61.1 | 32.1 | 40.4 | 23.8 | 37.7 | 6.6 | 58.9 | 7.9 | 10.0 | 4.6 | 46.4 | 7.3 |

| HDR + PC | 57.0 | 30.8 | 46.7 | 26.2 | 41.1 | 7.5 | 58.9 | 8.0 | 12.1 | 1.0 | 54.2 | 15.0 | |

| LDR + PC + Cet | 51.8 | 30.7 | 54.7 | 40.9 | 35.8 | 8.0 | 63.4 | 11.6 | 12.4 | 7.3 | 43.8 | 6.6 | |

| HDR + PC + Cet | 54.0 | 37.0 | 59.0 | 46.9 | 44.0 | 16.0 | 51.0 | 6.0 | 17.0 | 6.0 | 54.0 | 19.0 | |

| PROCLAIM [42] | RT + PP | 36.7 | 22.6 | 42.8 | 24.4 | 55.0 | 40.3 | 40.3 | 8.8 | 17.0 | 1.8 | 48.1 | 15.5 |

| RT + EP | 40.8 | 30.1 | 54.8 | 44.5 | 85.0 | 29.0 | 45.6 | 13.6 | 10.7 | 2.6 | 50.7 | 20.6 | |

| CAMS [43] |

RT + EP RT + PC |

95.8 92.7 |

30.5 20.7 |

NR NR |

NR NR |

12.7 5.2 |

0 0 |

24.2 13.5 |

0 0 |

76.8 72.9 |

7.4 8.3 |

87.0 84.0 |

20.0 6.3 |

| WJOG5008L [44] | RT + SP | 96.3 | 40.7 | 88.9 | 33.3 | 42.6 | 9.3 | 79.6 | 25.5 | 24.1 | 9.3 | 66.7 | 3.7 |

| RT + VP | 100 | 79.6 | 94.4 | 75.9 | 22.0 | 3.7 | 88.9 | 27.8 | 20.4 | 7.4 | 74.1 | 0.0 | |

CRT Chemoradiotherapy, RT Radiotherapy, LDR Low dose radiation, HDR High dose radiation, VP Vinblastine plus cisplatin, EP Etoposide plus cisplatin, PC Paclitaxel plus carboplatin, Cet Cetuximab, PP Pemetrexed plus cisplatin, SP S1 plus cisplatin, NR Not reported

Our pooled analysis has several limitations. Firstly, four in seven included studies belonged to single-arm trial and lacked a comparative control group, and another three of the studies were prospective cohort trials with a comparative control group, they were of non-random design and lacked sufficient data to facilitate effective analysis, Secondly, heterogeneity of the dose regimen or endostatin usage between studies was not taken into consideration, resulting in unstable merged findings. Thirdly, the current results suggest that endostatin combined with RT alone is comparable to endostatin with CCRT in terms of ORR, LCR, and survival. However, the differences in efficacy and safety between the two treatment methods remain to be established. Further well-designed prospective randomized controlled clinical trials are warranted to reach definitive conclusions.

Increasing interest has emerged in studying the feasibility of combined radiotherapy, antiangiogenic agents and ICIs. Current evidence suggests that antiangiogenic agents have the potential for increasing the response to immunotherapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME) [53]. The IMpower150 study identified the synergic effect of antiangiogenic agents plus immunotherapy [54], in which patients in the atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and paclitaxel/carboplatin (ABCP) group achieved survival advantage over those in the bevacizumab plus paclitaxel/carboplatin (BCP) group. Similarly, preclinical study showed that endostatin plus anti-PD-1 also exerted a synergic effect on tumor growth in murine models of Lewis lung carcinoma by improving the TME and inducing autophagy [55]. An ongoing clinical trial (NCT04094909) is investigating the efficacy and safety of endostatin combined with chemotherapy and pembrolizumab as first-line therapy in patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC. Despite the lack of clinical trials involving the combination therapy of endostatin, ICIs and RT/CRT, the synergic effect between endostatin and ICIs/RT will provide a potential way to improve clinical benefits for these patients when compared with current standard treatment.

Conclusion

Based on this pooled data analysis, adding recombinant human endostatin to radiotherapy or concurrent chemoradiotherapy is an effective and less toxic method for the treatment of patients with unresectable LA-NSCLC. We suggest that concurrent administration of endostatin and CRT or RT presents a promising treatment approach for some patients in the era when CRT plus durvalumab has become the current standard of care. For patients who cannot tolerate CCRT and ICIs, endostatin combined with RT alone may be a good alternative, but for those patients who can tolerate CCRT but cannot tolerate ICIs, addition of endostatin to CCRT may become a more effective treatment strategy. High-quality prospective studies are needed to validate this suggestion. Given the synergistic antitumor effect of antiangiogenic agents and RT/ICIs on lung cancer, triple- or quadruple- combination therapy of endostatin, ICIs and RT/CRT for patients with inoperable stage III NSCLC might become a potential strategy in the future. However, multiple challenges regarding this combination remain to be addressed before it can be applied to clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

None.

Abbreviations

- AEs

Adverse events

- CCRT

Concurrent chemoradiotherapy

- CI

Confidence interval

- CIV

Continuous intravenous pumping

- CRT

Chemoradiotherapy

- ECRT

Endostatin plus concurrent chemoradiotherapy

- ERT

Endostatin plus radiotherapy

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- ICIs

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

- IV

Intravenous injection

- LA-NSCLC

Locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer

- LCR

Local control rate

- NSCLC

Non-small cell lung cancer

- ORR

Objective response rate

- OS

Overall survival

- PFS

Progression-free survival

- PS

Performance status

- RCTs

Randomized controlled trials

- RT

Radiotherapy

- TME

Tumor microenvironment

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

Authors’ contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission. CH and JM conceived and designed the project; SZ, LS, and LH performed the project; SZ analyzed the data and wrote the paper; JM was the Senior Author who oversaw the project.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the 345 Talent Project of Shengjing Hospital.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All analyses were based on previously published studies, and hence no ethical approval and patient consent were required.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Shu-Ling Zhang, Email: zhshuling150@163.com.

Cheng-Bo Han, Email: han_cb@126.com.

Li Sun, Email: lisun_1009@126.com.

Le-Tian Huang, Email: letian91k@163.com.

Jie-Tao Ma, Email: ma_jt@126.com.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wistuba II, Gelovani JG, Jacoby JJ, Davis SE, Herbst RS. Methodological and practical challenges for personalized cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8(3):135–141. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang P, Allen MS, Aubry MC, Wampfler JA, Marks RS, Edell ES, et al. Clinical features of 5,628 primary lung cancer patients: experience at Mayo Clinic from 1997 to 2003. Chest. 2005;128(1):452–462. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auperin A, Le Pechoux C, Rolland E, Curran WJ, Furuse K, Fournel P, et al. Meta-analysis of concomitant versus sequential radiochemotherapy in locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2181–2190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curran WJ, Jr, Paulus R, Langer CJ, Komaki R, Lee JS, Hauser S, et al. Sequential vs. concurrent chemoradiation for stage III non-small cell lung cancer: randomized phase III trial RTOG 9410. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(19):1452–1460. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criss SD, Mooradian MJ, Sheehan DF, Zubiri L, Lumish MA, Gainor JF, et al. Costeffectiveness and Budgetary Consequence Analysis of Durvalumab Consolidation Therapy vs No Consolidation Therapy After Chemoradiotherapy in Stage III Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer in the Context of the US Health Care System. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(3):358–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Uemura T, Hida T. Durvalumab showed long and durable effects after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small cell lung cancer: results of the PACIFIC study. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10(Suppl 9):S1108–S1S12. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.03.180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonia SJ, Villegas A, Daniel D, Vicente D, Murakami S, Hui R, et al. Overall survival with Durvalumab after Chemoradiotherapy in stage III NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(24):2342–2350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1809697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toma-Dasu I, Dasu A, Karlsson M. The relationship between temporal variation of hypoxia, polarographic measurements and predictions of tumour response to radiation. Phys Med Biol. 2004;49(19):4463–4475. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/49/19/002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seo Y, Yan T, Schupp JE, Colussi V, Taylor KL, Kinsella TJ. Differential radiosensitization in DNA mismatch repair-proficient and -deficient human colon cancer xenografts with 5-iodo-2-pyrimidinone-2′-deoxyribose. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10(22):7520–7528. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ansiaux R, Baudelet C, Jordan BF, Crokart N, Martinive P, DeWever J, et al. Mechanism of reoxygenation after antiangiogenic therapy using SU5416 and its importance for guiding combined antitumor therapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66(19):9698–9704. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Provencio M, Sanchez A. Therapeutic integration of new molecule-targeted therapies with radiotherapy in lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2014;3(2):89–94. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2014.03.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lind JS, Senan S, Smit EF. Pulmonary toxicity after bevacizumab and concurrent thoracic radiotherapy observed in a phase I study for inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(8):e104–e108. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang XD, Dai P, Qiao Y, Wu J, Song DA, Li SQ. Clinical study on the recombinant human endostatin regarding improving the blood perfusion and hypoxia of non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2012;14(6):437–443. doi: 10.1007/s12094-012-0821-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng MB, Jiang XD, Deng L, Na FF, He JZ, Xue JX, et al. Enhanced radioresponse with a novel recombinant human endostatin protein via tumor vasculature remodeling: experimental and clinical evidence. Radiother Oncol. 2013;106(1):130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2012.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang XD, Dai P, Wu J, Song DA, Yu JM. Effect of recombinant human endostatin on radiosensitivity in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(4):1272–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang X, Guan W, Li M, Liang W, Qing Y, Dai N, et al. Endostatin combined with platinum-based chemo-radiotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;71(2):571–577. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhai YR, Hui Z, Ma H, Zhao L, Li D, Liang J, et al. HELPER study: a phase II trial of continuous infusion of endostar combined with concurrent etoposide plus cisplatin and radiotherapy for treatment of unresectable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2019;131:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2018.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jadad ARMR, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells GA SB, O'Connell D, Peterson J , Welch V, Losos M , Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa Hospital Research Institute website. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. [updated 2015/12/29.

- 21.Sun XJ, Deng QH, Yu XM, Ji YL, Zheng YD, Jiang H, et al. A phase II study of Endostatin in combination with paclitaxel, carboplatin, and radiotherapy in patients with unresectable locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:266. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2234-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bao Y, Peng F, Zhou QC, Yu ZH, Li JC, Cheng ZB, et al. Phase II trial of recombinant human endostatin in combination with concurrent chemoradiotherapy in patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2015;114(2):161–166. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tang H, Ma H, Peng F, Bao Y, Hu X, Wang J, et al. Prognostic performance of inflammation-based prognostic indices in locally advanced non-small-lung cancer treated with endostar and concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Mol Clin Oncol. 2016;4(5):801–806. doi: 10.3892/mco.2016.796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen C, Zhang LZ. The observation of short-term effects of YH-16 combined with concurrent three dimensional conformal radiotherapy on LocallyAdvancedNon-small cell lung Cancer. J Basic Clin Oncol. 2009;22(3):218–220. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Q, Shi Q, Xie Q. Preliminary study of recombinant human endostatin(Endostar)combined with concurrent intensity-modulated radiation therapy for inoperable local advanced non-small cell lung cancer in elderly patients. Chin J of Oncol Prev and Treat. 2017;9(2):132–145. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma JT, Sun J, Sun L, Zhang SL, Huang LT, Han CB. Efficacy and safety of apatinib in patients with advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer that failed prior chemotherapy or EGFR-TKIs: a pooled analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(35):e12083. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000012083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis--correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(1):1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ingber D, Fujita T, Kishimoto S, Sudo K, Kanamaru T, Brem H, et al. Synthetic analogues of fumagillin that inhibit angiogenesis and suppress tumour growth. Nature. 1990;348(6301):555–557. doi: 10.1038/348555a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bae DG, Gho YS, Yoon WH, Chae CB. Arginine-rich anti-vascular endothelial growth factor peptides inhibit tumor growth and metastasis by blocking angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(18):13588–13596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vasudev NS, Reynolds AR. Anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer: current progress, unresolved questions and future directions. Angiogenesis. 2014;17(3):471–494. doi: 10.1007/s10456-014-9420-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sunshine SB, Dallabrida SM, Durand E, Ismail NS, Bazinet L, Birsner AE, et al. Endostatin lowers blood pressure via nitric oxide and prevents hypertension associated with VEGF inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(28):11306–11311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203275109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, Xiong J, Wu C, Bai Y, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of Apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or Gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(13):1448–1454. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.5995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein A, Loewenstein A. Therapeutic monoclonal antibodies and fragments: Bevacizumab. Dev Ophthalmol. 2016;55:232–245. doi: 10.1159/000431199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rong B, Yang S, Li W, Zhang W, Ming Z. Systematic review and meta-analysis of Endostar (rh-endostatin) combined with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treating advanced non-small cell lung cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:170. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garon EB, Ciuleanu TE, Arrieta O, Prabhash K, Syrigos KN, Goksel T, et al. Ramucirumab plus docetaxel versus placebo plus docetaxel for second-line treatment of stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer after disease progression on platinum-based therapy (REVEL): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;384(9944):665–673. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60845-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brizel DM, Sibley GS, Prosnitz LR, Scher RL, Dewhirst MW. Tumor hypoxia adversely affects the prognosis of carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38(2):285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brizel DM, Hage WD, Dodge RK, Munley MT, Piantadosi CA, Dewhirst MW. Hyperbaric oxygen improves tumor radiation response significantly more than carbogen/nicotinamide. Radiat Res. 1997;147(6):715–720. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sonveaux P. Provascular strategy: targeting functional adaptations of mature blood vessels in tumors to selectively influence the tumor vascular reactivity and improve cancer treatment. Radiother Oncol. 2008;86(3):300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peng Q, Li M, Wang Z, Jiang M, Yan X, Lei S, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated macrophage is associated with tumor vascular normalization by endostatin. Thorac Cancer. 2013;4(3):295–305. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu JB, Tang YL, Liang XH. Targeting VEGF pathway to normalize the vasculature: an emerging insight in cancer therapy. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:6901–6909. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S172042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bradley JD, Paulus R, Komaki R, Masters G, Blumenschein G, Schild S, et al. Standard-dose versus high-dose conformal radiotherapy with concurrent and consolidation carboplatin plus paclitaxel with or without cetuximab for patients with stage IIIA or IIIB non-small-cell lung cancer (RTOG 0617): a randomised, two-by-two factorial phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(2):187–199. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71207-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Senan S, Brade A, Wang LH, Vansteenkiste J, Dakhil S, Biesma B, et al. PROCLAIM: randomized phase III trial of Pemetrexed-Cisplatin or Etoposide-Cisplatin plus thoracic radiation therapy followed by consolidation chemotherapy in locally advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(9):953–962. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liang J, Bi N, Wu S, Chen M, Lv C, Zhao L, et al. Etoposide and cisplatin versus paclitaxel and carboplatin with concurrent thoracic radiotherapy in unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(4):777–783. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sasaki T, Seto T, Yamanaka T, Kunitake N, Shimizu J, Kodaira T, et al. A randomised phase II trial of S-1 plus cisplatin versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin with concurrent thoracic radiotherapy for unresectable, locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer: WJOG5008L. Br J Cancer. 2018;119(6):675–682. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in Oncology: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer(2020.V6) [Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx#nscl.

- 46.Lin SH, Lin Y, Yao L, Kalhor N, Carter BW, Altan M, et al. Phase II trial of concurrent Atezolizumab with Chemoradiation for Unresectable NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(2):248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peters S, Ruysscher DD, Dafni U, Felip E, Guckenberger M, Vansteenkiste JF, et al. Safety evaluation of nivolumab added concurrently to radiotherapy in a standard first line chemo-RT regimen in unresectable locally advanced NSCLC: The ETOP NICOLAS phase II trial. Lung Cancer. 2018;36(15_suppl):8510. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al-Shamsi HO, Al Farsi A, Ellis PM. Stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: establishing a benchmark for the proportion of patients suitable for radical treatment. Clin Lung Cancer. 2014;15(4):274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2014.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jiang XD, Qiao Y, Dai P, Chen Q, Wu J, Song DA, et al. Enhancement of recombinant human endostatin on the radiosensitivity of human pulmonary adenocarcinoma A549 cells and its mechanism. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:301931. doi: 10.1155/2012/301931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Travis WDCT, Corrin B, et al. In Collaboration with L.H. Sobin and Pathologists from 14 Countries. Histological Typing of Lung and Pleural Tumours (International Histological Classification of Tumours) Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cheng Y, Nie L, Liu Y, Jin Z, Wang X, Hu Z. Comparison of Endostar continuous versus intermittent intravenous infusion in combination with first-line chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10(7):1576–1580. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Honglian M, Zhouguang H, Fang P, Lujun Z, Dongming L, Yujin X, et al. Different administration routes of recombinant human endostatin combined with concurrent chemoradiotherapy might lead to different efficacy and safety profile in unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer: updated follow-up results from two phase II trials. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11(4):898–906. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang Y, Yuan J, Righi E, Kamoun WS, Ancukiewicz M, Nezivar J, et al. Vascular normalizing doses of antiangiogenic treatment reprogram the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and enhance immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(43):17561–17566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215397109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Socinski MA, Jotte RM, Cappuzzo F, Orlandi F, Stroyakovskiy D, Nogami N, et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of metastatic nonsquamous NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(24):2288–2301. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1716948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu J, Zhao X, Sun Q, Jiang Y, Zhang W, Luo J, et al. Synergic effect of PD-1 blockade and endostar on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR-mediated autophagy and angiogenesis in Lewis lung carcinoma mouse model. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;125:109746. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.109746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.