Abstract

Purpose:

The aim of this study is to analyze the effect of internal limiting membrane peeling in removal of idiopathic epiretinal membranes through meta-analysis.

Methods:

We searched PubMed for studies published until 30 April 2018. Inclusion criteria included cases of idiopathic epiretinal membranes, treated with vitrectomy with or without internal limiting membrane peeling. Exclusion criteria consisted of coexisting retinal pathologies and use of indocyanine green to stain the internal limiting membrane. Sixteen studies were included in our meta-analysis. We compared the results of surgical removal of epiretinal membrane, with or without internal limiting membrane peeling, in terms of best-corrected visual acuity and anatomical restoration of the macula (central foveal thickness). Studies or subgroups of patients who had indocyanine green used as an internal limiting membrane stain were excluded from the study, due to evidence of its toxicity to the retina.

Results:

Regarding best-corrected visual acuity levels, the overall mean difference was –0.29 (95% confidence interval: –0.319 to –0.261), while for patients with internal limiting membrane peeling was –0.289 (95% confidence interval: –0.334 to –0.244) and for patients without internal limiting membrane peeling was –0.282 (95% confidence interval: –0.34 to –0.225). Regarding central foveal thickness levels, the overall mean difference was –117.22 (95% confidence interval: –136.70 to –97.74), while for patients with internal limiting membrane peeling was –121.08 (95% confidence interval: –151.12 to –91.03) and for patients without internal limiting membrane peeling was –105.34 (95% confidence interval: –119.47 to –96.21).

Conclusion:

Vitrectomy for the removal of epiretinal membrane combined with internal limiting membrane peeling is an effective method for the treatment of patients with idiopathic epiretinal membrane.

Keywords: epiretinal membrane, internal limiting membrane, macular pucker, peeling

Introduction

Epiretinal membrane (ERM) is a quite common disorder of the vitreomacular interface. Studies have reported the prevalence of ERM, ranging from 7.0% to 11.8% and have shown differences in prevalence across ethnicities.1,2 Systemic factors have also been found to be associated significantly with the formation of the membrane like age and hypertriglyceridemia.3 Its presence can cause visual impairment which can be significant and affect the quality of life of patients, requiring surgical treatment for the peeling of the membrane. Current knowledge about the pathogenesis points to a pathologic proliferation of cells (glial, retinal pigment epithelium cells, and myofibroblasts) that migrate through defects in the internal limiting membrane (ILM).4,5

In cases of idiopathic ERMs, the traction exerted on the retina causes the proliferation of Müller cells through cellular protein mediators (GFAP, vimentin) in a process called gliosis. These defects may occur in the absence of any pathologic situations near retinal vessels. Larger breaks may occur due to posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) in paravascular areas.6–8

Moreover, during vitreoschisis, when it occurs anterior to the level of hylocytes, a cellular layer is left on the macula.9 Hylocytes lying on the macular surface proliferate, recruit glial cells and induce collagen fibers contraction.10

Advances in optical coherence tomography have revealed detailed features of macular anatomy. These features serve as prognostic factors for visual acuity (VA) recovery after surgical removal of ERMs. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and central foveal thickness (CFT) are the commonest factors examined for the assessment of patients with ERM.11–15 BCVA is measured in logarithmic scale for statistical analysis. CFT is measured using spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT).

Indocyanine green (ICG) is a dye that has been widely used for the staining of ILM in vitreoretinal surgery. However, due to findings pointing the retinal toxicity of this dye, during the past years, it has been mainly replaced by trypan blue and brilliant blue G for ERM surgery.

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to study the effect of ILM peeling in surgical removal of ERMs.

Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

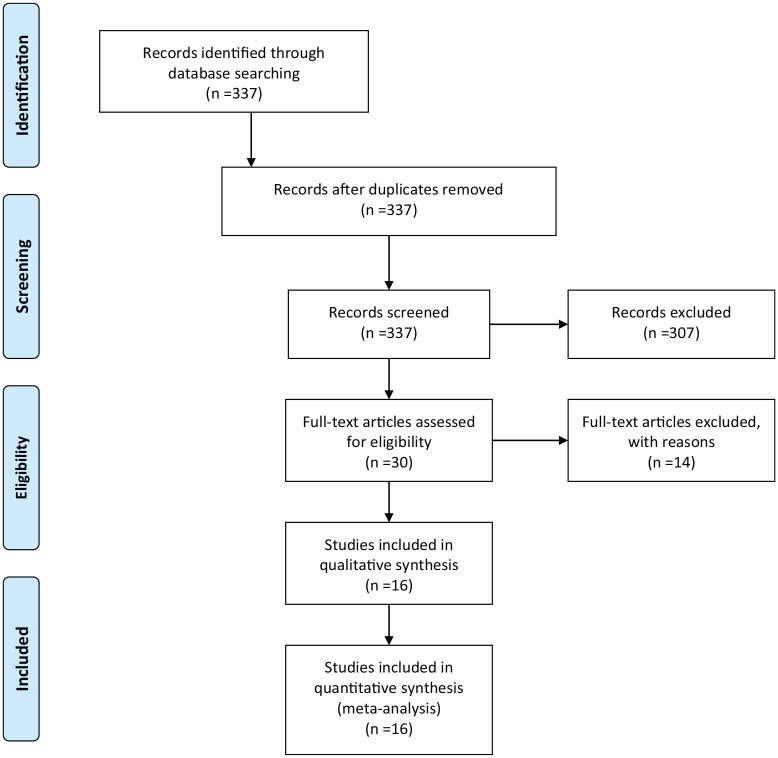

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. We considered all studies regarding surgical treatment of patients with macular pucker comparing membrane peeling with or without ILM removal but also studies of surgical removal with ILM removal standalone. We searched PubMed using the following keywords (terms): (epiretinal membrane OR macular pucker) AND (ILM) AND (peel or peeling). We searched for studies published in English language, until 30 April 2018. The first search retrieved 337 studies. Three-hundred and seven papers were excluded after title/abstract screening. Thirty articles were read in full text, 12 were excluded for ICG being used for ILM peeling and 2 during data extraction because standard deviation values, necessary for statistical analysis, were missing. Finally, 16 studies were included in meta-analysis16–31 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Inclusion criteria included cases of idiopathic ERMs, treated with vitrectomy with or without ILM peeling and assessed for logMAR BCVA and foveal thickness measurement. Exclusion criteria consisted of coexisting retinal pathologies and the use of ICG to stain the ILM. Studies (or subgroups of studies) where ICG had been used were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

The data were independently extracted by two reviewers and rechecked after the first extraction. We recorded information on study characteristics and demographics such as authors, publication year and journal, sample size, treatment modality (with or without ILM peeling) preoperative and postoperative VA in LogMAR, preoperative and postoperative central macular thickness in μm. Totally 16 studies were included16–31 (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Data extracted regarding BCVA in logMAR.

| Study | PMID | Year | Method | Patients | Preoperative BCVA | SD preoperative BCVA | BCVA 6 months or longer | SD BCVA 6 months or longer | Change | SD change | SE change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lim and colleagues16 | 20,689,783 | 2010 | With ILM peel | 18 | 0.43 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.29 | −0.21 | 0.280535 | 0.066123 |

| Obata and colleagues17 | 27,760,434 | 2017 | Without ILM peel | 61 | 0.32 | 0.26 | 0.05 | 0.18 | −0.27 | 0.230651 | 0.029532 |

| Deltour and colleagues18 | 27,429,376 | 2017 | With ILM peel (actively) | 22 | 0.34 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.23 | −0.19 | 0.199249 | 0.04248 |

| Deltour and colleagues18 | 27,429,376 | 2017 | With ILM peel (spontaneously) | 10 | 0.25 | 0.18 | 0.1 | 0.05 | −0.15 | 0.160935 | 0.050892 |

| Shimada and colleagues19 | 19,427,701 | 2009 | With ILM peel (no stain) | 46 | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.28 | −0.28 | 0.296142 | 0.043664 |

| Shimada and colleagues19 | 19,427,701 | 2009 | With ILM peel (TA) | 42 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.3 | −0.28 | 0.305123 | 0.047081 |

| Shimada and colleagues19 | 19,427,701 | 2009 | With ILM peel (BBG) | 54 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.23 | 0.26 | −0.36 | 0.32187 | 0.043801 |

| Kwok and colleagues20 | 16,033,350 | 2005 | Without ILM peel | 17 | 0.96 | 0.18 | 0.65 | 0.32 | −0.31 | 0.277849 | 0.067388 |

| Mayer and colleagues21 | 26,421,182 | 2015 | With ILM peel | 42 | 0.60 | 0.20 | 0.2 | 0.2 | −0.4 | 0.2 | 0.030861 |

| Tari and colleagues22 | 17,558,317 | 2007 | With ILM peel | 10 | 0.40 | 0.11 | 0.2 | 0.14 | −0.2 | 0.131149 | 0.043716 |

| Pournaras and colleagues23 | 21,469,962 | 2011 | Without ILM peel | 15 | 0.48 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.42 | −0.11 | 0.363868 | 0.09395 |

| Ripandelli and colleagues24 | 25,158,943 | 2015 | With ILM peel | 30 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Ripandelli and colleagues24 | 25,158,943 | 2015 | Without ILM peel | 30 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Lee and colleagues25 | 20,401,561 | 2010 | Without ILM peel | 19 | 0.67 | 0.34 | 0.32 | 0.23 | −0.35 | 0.3005 | 0.068939 |

| Ahn and colleagues26 | 23,743,638 | 2014 | Without ILM peel | 69 | 0.31 | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.12 | −0.2 | 0.182483 | 0.021968 |

| Machado and colleagues27 | 25,932,723 | 2015 | With ILM peel | 31 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Tranos and colleagues28 | 28,045,374 | 2017 | Without ILM peel | 52 | 0.55 | 0.05 | n/a | n/a | −0.31 | 0.23 | 0.031895 |

| Tranos and colleagues28 | 28,045,374 | 2017 | With ILM peel | 50 | 0.50 | 0.04 | n/a | n/a | −0.3 | 0.24 | 0.033941 |

| De Novelli and colleagues29 | 29,215,533 | 2019 | Without ILM peel | 35 | 0.67 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.25 | −0.4 | 0.272213 | 0.046012 |

| De Novelli and colleagues29 | 29,215,533 | 2019 | With ILM peel | 28 | 0.63 | 0.31 | 0.43 | 0.43 | −0.2 | 0.384318 | 0.072629 |

| Kumar and colleagues30 | 26,659,009 | 2016 | With ILM peel | 44 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.13 | −0.41 | 0.141067 | 0.021267 |

| Manousaridis and colleagues31 | 26,499,510 | 2016 | With ILM peel | 20 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | −0.3 | 0.173205 | 0.03873 |

BCVA, best-corrected visual acuity; ILM, internal limiting membrane; TA: triamcinolone; BBG: brilliant blue G; PMID: PubMed IDentifier.

Table 2.

Data extracted regarding CFT in μm.

| Study | PMID | Year | Method | Patients | Preoperative CFT | SD preoperative CFT | CFT 6 months or longer | SD CFT 6 months or longer | Change | SD change | SE change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lim and colleagues.16 | 20,689,783 | 2010 | With ILM peel | 18 | 485 | 95.6 | 314.5 | 69.5 | −170.5 | 85.59 | 20.17 |

| Obata and colleagues.17 | 27,760,434 | 2017 | Without ILM peel | 61 | 463.6 | 80.7 | 369 | 60.2 | −94.6 | 72.65 | 9.30 |

| Deltour and colleagues.18 | 27,429,376 | 2017 | With ILM peel (actively) | 22 | 465.36 | 70.4 | 365.5 | 43.6 | −99.86 | 61.54 | 13.12 |

| Deltour and colleagues.18 | 27,429,376 | 2017 | With ILM peel (spontaneously) | 10 | 476.5 | 72.7 | 414.3 | 45.2 | −62.2 | 63.58 | 20.11 |

| Shimada and colleagues19 | 19,427,701 | 2009 | With ILM peel (no stain) | 46 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Shimada and colleagues19 | 19,427,701 | 2009 | With ILM peel (TA) | 42 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Shimada and colleagues19 | 19,427,701 | 2009 | With ILM peel (BBG) | 54 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Kwok and colleagues20 | 16,033,350 | 2005 | Without ILM peel | 17 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Mayer and colleagues.21 | 26,421,182 | 2015 | With ILM peel | 42 | 455.7 | 104.3 | 332.3 | 55.1 | −123.4 | 90.37 | 13.95 |

| Tari and colleagues22 | 17,558,317 | 2007 | With ILM peel | 9 | 433.33 | 75.51 | 330.67 | 32,29 | −102.66 | 65.62 | 21.87 |

| Pournaras and colleagues23 | 21,469,962 | 2011 | Without ILM peel | 15 | n/a | n/a | 268.0 | 98.0 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Ripandelli and colleagues24 | 25,158,943 | 2015 | With ILM peel | 30 | 464.2 | 89.2 | 376.9 | 45.12 | −87.3 | 77.25 | 14.10 |

| Ripandelli and colleagues24 | 25,158,943 | 2015 | Without ILM peel | 30 | 473.8 | 75.7 | 351.03 | 40.24 | −122.77 | 65.60 | 11.98 |

| Lee and colleagues25 | 20,401,561 | 2010 | Without ILM peel | 19 | 398.42 | 95.34 | 282.53 | 95.71 | −115.89 | 95.52 | 21.92 |

| Ahn and colleagues26 | 23,743,638 | 2014 | Without ILM peel | 69 | 445 | 99.3 | 356 | 58.9 | −89 | 86.49 | 10.41 |

| Machado and colleagues27 | 25,932,723 | 2015 | With ILM peel | 31 | 451.9 | 90.36 | 221.94 | 35.04 | −229.96 | 78.91 | 14.17 |

| Tranos and colleagues28 | 28,045,374 | 2017 | Without ILM peel | 52 | 540 | 113 | n/a | n/a | −134 | 93 | 12.90 |

| Tranos and colleagues28 | 28,045,374 | 2017 | With ILM peel | 50 | 512 | 120 | n/a | n/a | −125 | 103 | 14.57 |

| De Novelli and colleagues29 | 29,215,533 | 2019 | Without ILM peel | 35 | 486 | 125 | 377 | 82.5 | −109 | 110.09 | 18.61 |

| De Novelli and colleagues29 | 29,215,533 | 2019 | With ILM peel | 28 | 475 | 117 | 388 | 69.2 | −87 | 101.89 | 19.26 |

| Kumar and colleagues30 | 26,659,009 | 2016 | With ILM peel | 44 | 436.72 | 98.92 | 291.54 | 68.63 | −145.18 | 87.79 | 13.23 |

| Manousaridis and colleagues31 | 26,499,510 | 2016 | With ILM peel | 20 | 486 | 76 | 396 | 41 | −90 | 65.89 | 14.73 |

CFT, central foveal thickness; ILM, internal limiting membrane; PMID, PubMed IDentifier; TA, triamcinolone; BBG, brilliant blue G.

Statistical analysis and meta-analysis

We used mean BCVA and CFT, standard deviations, and sample sizes reported in the individual studies to calculate effect size in means of mean difference. Mean differences and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in after/baseline BCVA and CFT levels were calculated. A random effects model (DerSimonian Laird method) and the generic inverse variance method were used since the heterogeneity was moderate to high. Statistical level significance between after/baseline BCVA and CFT levels was set at 0.05. We checked for heterogeneity with Cochran’s Q-test, where p < 0.10 denotes statistically significant heterogeneity and quantified the degree of heterogeneity with the I2 index.32 Increased I2 index corresponds to increased heterogeneity, and values of 25%, 50%, and 75% are considered as low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively.33 Egger test and Begg & Mazumdar test were used for the estimation of publication bias (p > 0.1 in both tests indicates the absence of publication bias. Statistical analysis was performed with OpenMeta(analyst) software.

Results

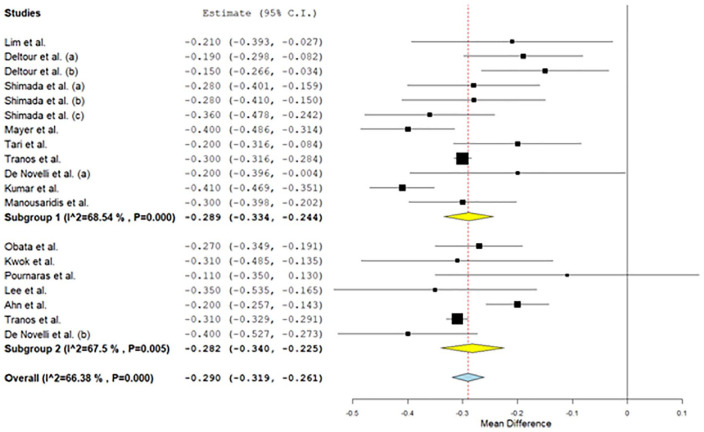

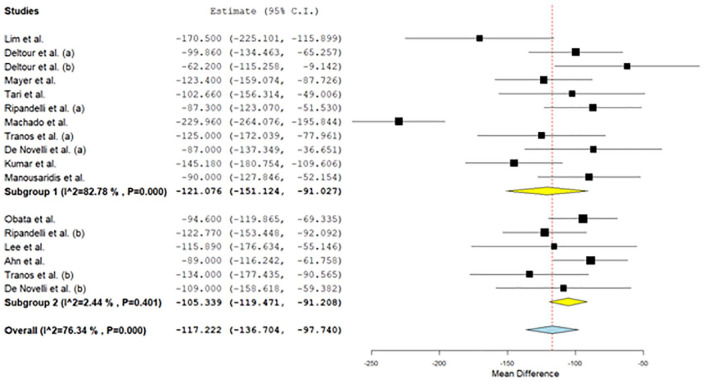

All studies found a statistically significant increase (p < 0.05) in postoperative BCVA and decrease in postoperative CFT levels versus preoperative levels. Regarding BCVA levels, the overall mean difference was –0.29 (95% CI: –0.319 to –0.261), while for patients with ILM peeling was –0.289 (95% CI: –0.334 to -0.244) and for patients without ILM peeling was –0.282 (95% CI: –0.34 to –0.225; Figure 2). Moderate heterogeneity between studies was found in all cases (I2 = 66.4% for all patients, I2 = 68.5% for patients with ILM peeling and I2 = 67.5% for patients without ILM peeling). There was publication bias (p = 0.011 for Egger test and p = 0.002 for Begg & Mazumdar test). In addition, regarding CFT levels, the overall mean difference was –117.22 (95% CI: –136.70 to –97.74), while for patients with ILM peeling was –121.08 (95% CI: –151.12 to –91.03) and for patients without ILM peeling was –105.34 (95% CI: –119.47 to –96.21; Figure 3). Low to high heterogeneity between studies was found (I2 = 76.3% for all patients, I2 = 82.8% for patients with ILM peeling and I2 = 2.4% for patients without ILM peeling). There was publication bias (p = 0.001 for Egger test and p = 0.003 for Begg & Mazumdar test).

Figure 2.

Results for preoperative–postoperative BCVA.

Figure 3.

Results for preoperative-postoperative CFT.

The risk of bias assessment was performed according to Newcastle Ottawa scale for non-randomized controlled trials (Table 3). For randomized controlled trials, we used the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Table 4).

Table 3.

Risk of bias – Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

| Study | Selection |

Comparability |

Exposure |

Total NOS star rating | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate definition of case | Representativeness of cases | Selection of controls | Definition of controls | Comparability of cases and controls | Ascertainment of exposure | Same method of ascertainment for cases and controls | Non-response rate | ||

| Lim and colleagues16 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

| Obata and colleagues17 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Deltour and colleagues18 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

| Shimada and colleagues19 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

| Kwok and colleagues20 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Mayer and colleagues21 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

| Tari and colleagues22 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

| Pournaras and colleagues23 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Lee and colleagues25 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Ahn and colleagues26 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Machado and colleagues27 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

| Kumar and colleagues30 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

| Manousaridis and colleagues31 | * | * | * | * | 4/9 | ||||

NOS: Newcastle Ottawa Scale

A study can be given a maximum of one star for each numbered item within the Selection and Outcome categories.

A maximum of two stars can be given for Comparability.

Table 4.

Cochrane Risk of Bias.

| Study | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | Other bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ripandelli and colleagues24 | + | + | − | ? | + | + | + |

| Tranos and colleagues28 | + | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| De Novelli and colleagues29 | + | + | − | ? | + | + | + |

: low risk of bias; –: high risk of bias, ?: unclear risk of bias.

Discussion

The ILM peeling for ERM removal is still a debate among vitreoretinal surgeons. However, the fact that ILM patches are peeled along the ERM peeling is proved through histopathology. The rationale for the ILM peeling is that it serves as a scaffold for cell proliferation and that it may bring remains of the ERM. Many studies have shown the superiority of ILM peeling in terms of recurrence rates.26,34–36 On the contrary, the removal of ILM affects the retinal cells, as it consists of Müller cell footplates. Studies have shown anatomical and functional alterations because of that however without affecting the final visual outcome of the intervention.24,37

So far, the meta-analyses published38–41 include studies that were carried out using ICG. Taking into account the proven toxicity of this dye, we considered conducting a meta-analysis including only either studies that did not use ICG at all, or parts of studies in case the authors discriminated groups using this dye or not.

The purpose of this article was to investigate the effect of the removal of ILM in the surgical treatment of ERMs regarding the anatomical and functional results. The technique of ILM removal is not new; however, through the years, there have been several dyes used to assist the peeling. ICG dye has been used widely in the past in order to stain ILM. However, its use has been dropped due to its toxic effects for the retina.42,43 Toxicity is attributed to ICG’s direct biochemical effects causing inner retinal cell defects and apoptosis of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells, through alterations in protein expression.44 It is concentration and exposure time dependent.45,46 ICG can also enhance light toxicity.47

Brilliant blue is found to have great affinity with ILM48 and is safer to use in comparison with ICG.49,50 When compared to triamcinolone for ILM peeling in cases of idiopathic macular holes, brilliant blue was found to be an effective alternative with good or even better anatomical and functional results.51,52 It is also superior for the visualization of the vitreomacular interface.52

Pars plana vitrectomy with ILM peeling is a broadly performed surgical intervention for posterior pole pathologies.53 Nevertheless, the peeling of the ILM results in changes of the nerve fiber layer (RNFL) due to exerted mechanical forces. The early changes consist of swelling of the arcuate nerve fiber (SANFL).54 It is described as hypofluorescent arcuate striae in infrared and autofluorescence imaging that corresponds to hyper-reflection on spectral domain OCT.55 SANFL is suspected to be initiated at the point of forceps grasping rather than the ILM peeling traumatizing Müller cells’ footplates. Moreover, it resolves after a period of 2–3 months without affecting VA.53 After that period, dimples within the inner retina might appear, forming dark arcuate striae. This phenomenon is called dissociated optic nerve fiber layer (DONFL). It has been suggested that the pattern of DONFL is not actually damage, but it occurs from the irregular distribution of Muller cells which is denser among nerve fiber buntles.56 Despite these changes, DONFL is found not to affect VA.57,58 On the other hand, ERM removal with ILM peel, inspite of the visual gain may result in subtle multifocal ERG abnormalities detectable in 12 months after surgery.16 Regarding glaucoma patients, vitrectomy for ERM removal with ILM peeling is in general a safe procedure. Transient changes in temporal nerve fiber layer thickness do not affect VA,59 and visual fields do not deteriorate after vitrectomy for ERM with ILM peeling.60

An important limitation, concerns the fact that there are only few studies with histopathologic analysis for determining the extent of simultaneous ILM peel during ERM peeling. Also, it is unclear whether surgeons checked for positive ILM staining after the ERM removal. Brilliant blue facilitates the identification of residual ILM with double staining.19 It has been shown that in the majority of cases, ILM parts are removed along with the ERM.61 Histopathologic analysis confirms the use of dyes for the identification of ILM as a reliable method.62

Regarding risk of bias non-randomized controlled trials were assessed for selection, comparability, and exposure, whereas randomized controlled trials were assessed for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. The main weakness of our study is that only three of the studies included were randomized control trials. Investigators either applied one of the mentioned techniques or due to the use of ICG-assisted ILM peeling, one of the groups of patients was excluded. More randomized controlled studies are needed in order to get more safe results after comparing the two methods.

Conclusion

Both methods are effective in terms of improvement in VA and reduction of macular thickness. More randomized controlled studies are needed in order to compare the two techniques.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Eleni Christodoulou  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8503-9734

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8503-9734

Andreas Katsanos  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6623-8503

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6623-8503

Contributor Information

Eleni Christodoulou, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece.

Georgios Batsos, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece.

Petros Galanis, Center for Health Services Management and Evaluation, Department of Nursing, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece.

Christos Kalogeropoulos, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece.

Andreas Katsanos, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece.

Yannis Alamanos, Institute of Epidemiology, Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Corfu, Greece.

Maria Stefaniotou, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Ioannina, Ioannina, Greece.

References

- 1. Fraser-Bell S, Guzowski M, Rochtchina E, et al. Five-year cumulative incidence and progression of epiretinal membranes: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klein R, Klein BE, Wang Q, et al. The epidemiology of epiretinal membranes. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 1994; 92: 403–430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bae JH, Song SJ, Lee MY. Five-year incidence and risk factors for idiopathic epiretinal membranes. Retina 2019; 39: 753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bu SC, Kuijer R, Li XR, et al. Idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Retina 2014; 34: 2317–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bovey EH, Uffer S. Tearing and folding of the retinal internal limiting membrane associated with macular epiretinal membrane. Retina 2008; 28: 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bringmann A, Wiedemann P. Involvement of Müller glial cells in epiretinal membrane formation. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2009; 247: 865–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Foos RY. Vitreoretinal juncture: epiretinal membranes and vitreous. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1977; 16: 416–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gandorfer A, Schumann R, Scheler R, et al. Pores of the inner limiting membrane in flat-mounted surgical specimens. Retina 2011; 31: 977–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sebag J. Vitreoschisis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008; 246: 329–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kita T, Hata Y, Kano K, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 2 and connective tissue growth factor in proliferative vitreoretinal diseases: possible involvement of hyalocytes and therapeutic potential of Rho kinase inhibitor. Diabetes 2007; 56: 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Michalewski J, Michalewska Z, Cisiecki S, et al. Morphologically functional correlations of macular pathology connected with epiretinal membrane formation in spectral optical coherence tomography (SOCT). Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2007; 245: 1623–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watanabe A, Arimoto S, Nishi O. Correlation between metamorphopsia and epiretinal membrane optical coherence tomography findings. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 1788–1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ooto S, Hangai M, Takayama K, et al. High-resolution imaging of the photoreceptor layer in epiretinal membrane using adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy. Ophthalmology 2011; 118: 873–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Inoue M, Morita S, Watanabe Y, et al. Inner segment/outer segment junction assessed by spectral-domain optical coherence tomography in patients with idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Am J Ophthalmol 2010; 150: 834–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okamoto F, Sugiura Y, Okamoto Y, et al. Inner nuclear layer thickness as a prognostic factor for metamorphopsia after epiretinal membrane surgery. Retina 2015; 35: 2107–2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lim JW, Cho JH, Kim HK. Assessment of macular function by multifocal electroretinography following epiretinal membrane surgery with internal limiting membrane peeling. Clin Ophthalmol 2010; 4: 689–694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Obata S, Fujikawa M, Iwasaki K, et al. Changes in retinal thickness after vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane with and without internal limiting membrane peeling. Ophthalmic Research 2017; 57: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Deltour JB, Grimbert P, Masse H, et al. Detrimental effects of active internal limiting membrane peeling during epiretinal membrane surgery: microperimetric analysis. Retina 2017; 37: 544–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shimada H, Nakashizuka H, Hattori T, et al. Double staining with brilliant blue G and double peeling for epiretinal membranes. Ophthalmology 2009; 116: 1370–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kwok A, Lai TY, Yuen KS. Epiretinal membrane surgery with or without internal limiting membrane peeling. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2005; 33: 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mayer WJ, Fazekas C, Schumann R, et al. Functional and morphological correlations before and after video-documented 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with membrane and ILM peeling in patients with macular pucker. J Ophthalmol 2015; 2015: 297239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tari SR, Vidne-Hay O, Greenstein VC, et al. Functional and structural measurements for the assessment of internal limiting membrane peeling in idiopathic macular pucker. Retina 2007; 27: 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pournaras CJ, Emarah A, Petropoulos IK. Idiopathic macular epiretinal membrane surgery and ILM peeling: anatomical and functional outcomes. Semin Ophthalmol 2011; 26: 42–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ripandelli G, Scarinci F, Piaggi P, et al. Macular pucker: to peel or not to peel the internal limiting membrane? A microperimetric response. Retina 2015; 35: 498–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lee JW, Kim IT. Outcomes of idiopathic macular epiretinal membrane removal with and without internal limiting membrane peeling: a comparative study. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2010; 54: 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ahn SJ, Ahn J, Woo SJ, et al. Photoreceptor change and visual outcome after idiopathic epiretinal membrane removal with or without additional internal limiting membrane peeling. Retina 2014; 34: 172–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Machado LM, Furlani BA, Navarro RM, et al. Preoperative and intraoperative prognostic factors of epiretinal membranes using chromovitrectomy and internal limiting membrane peeling. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina 2015; 46: 457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tranos P, Koukoula S, Charteris DG, et al. The role of internal limiting membrane peeling in epiretinal membrane surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Ophthalmol 2017; 101: 719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. De Novelli FJ, Goldbaum M, Monteiro MLR, et al. Surgical removal of epiretinal membrane with and without removal of internal limiting membrane: comparative study of visual acuity, features of optical coherence tomography, and recurrence rate. Retina 2019; 39: 601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kumar K, Chandnani N, Raj P, et al. Clinical outcomes of double membrane peeling with or without simultaneous phacoemulsification/gas tamponade for vitreoretinal-interface-associated (VRI) disorders. Int Ophthalmol 2016; 36: 547–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Manousaridis K, Peter S, Mennel S. 20 g PPV with indocyanine green-assisted ILM peeling versus 23 g PPV with brilliant blue G-assisted ILM peeling for epiretinal membrane. Int Ophthalmol 2016; 36: 407–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2002; 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bovey EH, Uffer S, Achache F. Surgery for epimacular membrane: impact of retinal internal limiting membrane removal on functional outcome. Retina 2004; 24: 728–735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Park DW, Dugel PU, Garda J, et al. Macular pucker removal with and without internal limiting membrane peeling: pilot study. Ophthalmology 2003; 110: 62–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sandali O, El Sanharawi M, Basli E, et al. Epiretinal membrane recurrence: incidence, characteristics, evolution, and preventive and risk factors. Retina 2013; 33: 2032–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kim YJ, Lee KS, Joe SG, et al. Incidence and quantitative analysis of dissociated optic nerve fiber layer appearance: real loss of retinal nerve fiber layer. Eur J Ophthalmol 2018; 28: 317–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu H, Zuo S, Ding C, et al. Comparison of the effectiveness of pars plana vitrectomy with and without internal limiting membrane peeling for idiopathic retinal membrane removal: a meta-analysis. J Ophthalmol 2015; 97: 45–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Azuma K, Ueta T, Eguchi S, et al. Effects of internal limiting membrane peeling combined with removal of idiopathic epiretinal membrane: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Retina 2017; 37: 1813–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fang XL, Tong Y, Zhou YL, et al. Internal limiting membrane peeling or not: a systematic review and meta-analysis of idiopathic macular pucker surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2017; 101: 1535–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chang WC, Lin C, Lee CH, et al. Vitrectomy with or without internal limiting membrane peeling for idiopathic epiretinal membrane: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2017; 12: e0179105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Uemura A, Kanda S, Sakamoto Y, et al. Visual field defects after uneventful vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane with indocyanine green-assisted internal limiting membrane peeling. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 136: 252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Haritoglou C, Gandorfer A, Gass CA, et al. The effect of indocyanine-green on functional outcome of macular pucker surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2003; 135: 328–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rezai KA, Farrokh-Siar L, Ernest JT, et al. Indocyanine green induces apoptosis in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 137: 931–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Haritoglou C, Gass CA, Schaumberger M, et al. Long-term follow-up after macular hole surgery with internal limiting membrane peeling. Am J Ophthalmol 2002; 134: 661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haritoglou C, Gandorfer A, Gass CA, et al. Histology of the vitreoretinal interface after staining of the internal limiting membrane using glucose 5% diluted indocyanine and infracyanine green. Am J Ophthalmol 2004; 137: 345–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Rodrigues EB, Meyer CH, Mennel S, et al. Mechanisms of intravitreal toxicity of indocyanine green dye: implications for chromovitrectomy. Retina 2007; 27: 958–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Farah ME, Maia M, Penha FM, et al. The use of vital dyes during vitreoretinal surgery: chromovitrectomy. Dev Ophthalmol 2016; 55: 365–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hernandez F, Alpizar-Alvarez N, Wu L. Chromovitrectomy: an update. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2014; 9: 251–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Enaida H, Hisatomi T, Nakao S, et al. Chromovitrectomy and vital dyes. Dev Ophthalmol 2014; 54: 120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li SS, You R, Li M, et al. Internal limiting membrane peeling with different dyes in the surgery of idiopathic macular hole: a systematic review of literature and network meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol 2019; 12: 1917–1928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kumar A, Gogia V, Shah VM, et al. Comparative evaluation of anatomical and functional outcomes using brilliant blue G versus triamcinolone assisted ILM peeling in macular hole surgery in Indian population. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011; 249: 987–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pichi F, Lembo A, Morara M, et al. Early and late inner retinal changes after inner limiting membrane peeling. Int Ophthalmol 2014; 34: 437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Clark A, Balducci N, Pichi F, et al. Swelling of the arcuate nerve fiber layer after internal limiting membrane peeling. Retina 2012; 32: 1608–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scupola A, Grimaldi G, Abed E, et al. Arcuate nerve fiber layer changes after internal limiting membrane peeling in idiopathic epiretinal membrane. Retina 2018; 38: 1777–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Spaide RF. “Dissociated optic nerve fiber layer appearance” after internal limiting membrane removal is inner retinal dimpling. Retina 2012; 32: 1719–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ito Y, Terasaki H, Takahashi A, et al. Dissociated optic nerve fiber layer appearance after internal limiting membrane peeling for idiopathic macular holes. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 1415–1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mitamura Y, Ohtsuka K. Relationship of dissociated optic nerve fiber layer appearance to internal limiting membrane peeling. Ophthalmology 2005; 112: 1766–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Lyssek-Boron A, Wylegala A, Polanowska K, et al. Longitudinal changes in retinal nerve fiber layer thickness evaluated using avanti Rtvue-XR optical coherence tomography after 23G vitrectomy for epiretinal membrane in patients with open-angle glaucoma. J Healthc Eng 2017; 2017: 4673714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yoshida M, Kunikata H, Kunimatsu-Sanuki S, et al. Efficacy of 27-gauge vitrectomy with internal limiting membrane peeling for epiretinal membrane in glaucoma patients. J Ophthalmol 2019; 2019: 7807432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Carpentier C, Zanolli M, Wu L, et al. Residual internal limiting membrane after epiretinal membrane peeling: results of the Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study Group. Retina 2013; 33: 2026–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vila Sola D, Nienow C, Jurgens I. Assessment of the internal limiting membrane status when a macular epiretinal membrane is removed in a prospective study. Retina 2017; 37: 2310–2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]