Abstract

Communication in oncology has always been challenging. The new era of precision medicine complicates communication even further as a result of our increasing reliance on genomic data and the varying psychological responses to genomic-based treatments and their expected outcomes. The crux of the matter hinges on understanding communication. The informed consent process may require more attention in the precision medicine era. However, many of the communication issues are actually similar to perennial long-standing communication issues in oncology, which center on providing hope when breaking bad news and ensuring that adequate informed consent to treatments is obtained. This piece presents several common patient reactions to different precision medicine scenarios in oncology practice. We highlight these new communication issues that focus on clinical and ethical questions (ie, informed consent, shared decision making, patient autonomy, and uncertainty in oncologic treatments) and provide guidance on working with each scenario. In this article, we address common reactions of patients to genomic information and provide thoughtful communication suggestions using a Shared Decision Making framework to help patients cope with the inherent distress-provoking uncertainties in oncology practice.

INTRODUCTION

The practice of oncology depends on adequate communication between patients and clinicians. Although the science of cancer medicine is advancing exponentially, information technology advances are seriously impeding the critical component of face-to-face communication. The key communication issues in oncology are always two-fold: the delivery of emotionally charged bad news while sustaining hope in the presence of a life-threatening prognosis and ensuring that patients understand the information that is provided.1 The advent of precision medicine now complicates the discussion of these issues in oncology in significant ways.2,3 Although there is a growing emphasis on providing humanistic care in oncology (eg, palliative care initiatives), the increasingly complicated science and public hype, coupled with limited time to talk with patients in busy oncology clinics, significantly threaten this goal. Science and technology have yet again raced ahead of the human element, which depends on communication to foster those critical elements of mutual respect and trust.

The application of genomic medicine is now accessible for the majority of oncology patients because the cost of genomic sequencing has decreased 1 million–fold from a decade ago.4-6 The development of molecular diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers continues to change the landscape of clinical oncology.7 Furthermore, technologic advances facilitate the use of large-scale databases that store genomic data, such as ASCO’s CancerLinQ and IBM Watson.8-11 Also, research trial design in precision oncology is evolving from the randomized controlled trial to designs that harness these large data-collection initiatives and evaluate responses to drugs across multiple cancer subtypes (ie, basket trial design).12,13

At the same time that genomic science and technology have created new research and clinical treatment paradigms, social media and drug direct-to-consumer marketing in the United States has brought information to the public with remarkable speed and fervor.14,15 Although there are advantages to patients being informed consumers, handling this complex information without any interpretation of its meaning is not helpful.16 This breadth and rapidity of information adds an additional strain to the already complicated communication that occurs between clinicians and their patients.17 Direct-to-consumer marketing is new and often amplifies drug benefits beyond reality. Clinicians are not trained to manage patients’ new level of expectations as the result of advertising. Exaggerated hopes in many cases are unrealistic and will result in disappointment for patients when confronted with the reality of their situation. Nor do we understand the implications for the overall cancer experience, eg, their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their oncology care, or how this information influences patients’ treatment choices.15 Its implications may be greatest when considering the delicate end-of-life conversations that are critical to quality oncology care.18

Therefore, it is critical that we understand patients’ experiences in this new technologic age of genomic medicine. We should seek to engage patients’ fears, hopes, and frustrations about precision medicine. The Shared Decision Making (SDM) model of communication promotes patient activation and engagement in health care and is an optimal model to guide communication tasks in the precision medicine era.19,20

The SDM model describes how clinician and patient jointly participate in making a health decision, having discussed the options and their benefits and harms, as well as having considered the patient’s values, preferences, and circumstances. SDM is a central element of patient-centered communication. It respects patient autonomy and leads to improved patient satisfaction when patients are faced with clinical options for which there is not a clearly correct choice, as is frequently encountered in the context of precision oncology.21-24

In this article, we highlight the psychological, social, and ethical issues that are part of our new treatments, and we provide communication suggestions on the basis of SDM. Communication training has been shown to improve communication and can be used to meet our patients’ communication needs in this new era of precision oncology.25,26

PATIENT REACTIONS TO PRECISION MEDICINE IN ONCOLOGY AND SUGGESTED COMMUNICATION STRATEGIES USING THE SDM MODEL

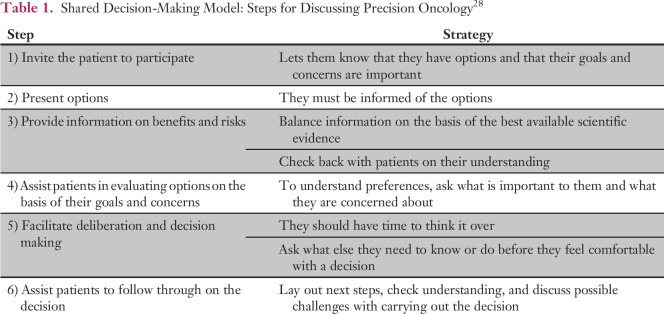

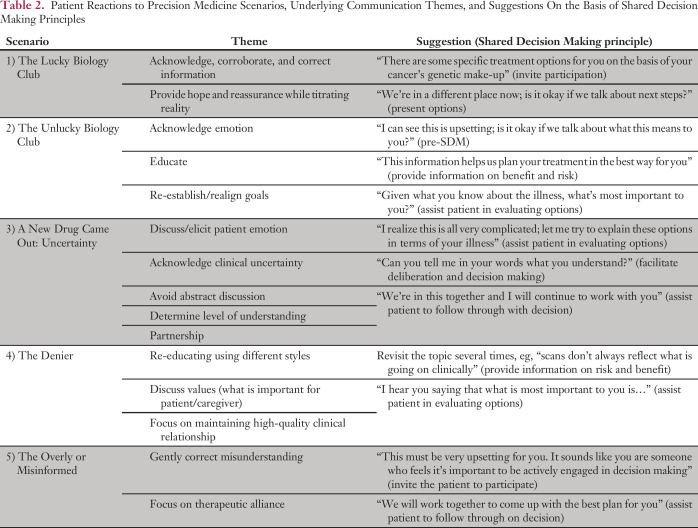

SDM principles can be used to help clarify communication goals (Table 1).27,28 Several themes have emerged that may help to guide communication practices in precision oncology. They reflect a range of psychological reactions and are variations of normal reactions (Table 2). They do not represent psychiatric disorders. Patients’ emotional reactions should be considered before, during, and after SDM to ensure effective communication.

Table 1.

Shared Decision-Making Model: Steps for Discussing Precision Oncology28

Table 2.

Patient Reactions to Precision Medicine Scenarios, Underlying Communication Themes, and Suggestions On the Basis of Shared Decision Making Principles

“I Won the Lottery”: The Lucky Biology Club Member

Jane was a 58-year-old teacher who was diagnosed with stage IV adenocarcinoma of the lung that harbored an epidermal growth factor receptor mutation. Her cancer responded well to erlotinib. Jane thought that her mutation made her invincible as long as she kept taking the drug, despite being told initially that eventually the drug would stop working. She continued to feel well and work fulltime; she was not concerned about advanced care planning. After 15 months, her cancer began to grow as it became increasingly resistant to erlotinib, and chemotherapy was required to treat it. Jane became extremely angry and frustrated that her cancer had progressed and found it hard to appreciate the benefit that the drug provided in light of its failure. She remained in shock and disbelief and had a difficult time accepting the need to adjust her treatment to the new situation.

The Lucky Biology Club members have driver actionable mutations such as epidermal growth factor receptor, anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ROS1, and BRAFV600E. Patients may feel so relieved by their perceived good luck that they cannot accept the fact that they have an incurable disease. They have usually read on the Internet about the mutation and its prognostic implications. There is often a sentiment such as, “I’ve won the lottery,” and they may feel that their mutation is special. Clinicians may share their excitement and say things such as, “This is great news,” or “We have promising new treatments for your mutation.” This encouragement from clinicians may cause a false sense of security that complicates decision making later, when the disease progresses. Patients often think, “I have plenty of time” or “There will always be another drug for me after this one.” Subsequently, discussions about health care proxies, financial planning, and wills are often delayed.

In terms of discussion, it is important to acknowledge the implications of disease biology and to corroborate and correct the information that they have from other sources. Using SDM principles, the clinician could initiate a discussion of options by saying, “There are some specific treatment options for you, on the basis of your cancer’s genomic make-up.” However, the clinician must also discuss the framework for treatment and prognosis: “Although the cancer is still not curable, the mutation indicates that we have some additional treatment options. Let’s start this drug and assess how you do,” and “When the cancer becomes resistant, we may add another drug or switch to chemotherapy.” When the cancer progresses, it is important to address the transition in terms of goals. The clinician may say, “Given this news, it seems like a good time to talk about what to do next” or “We are in a different place now. Is it okay if we talk more about the other options and next steps?”

Addressing the underlying emotions and acknowledging fear are important tools that should be dealt with before focusing on SDM. For example, it is important to acknowledge the emotion underlying the uncertainty before and after each scan interval. The Lucky Biology Club patient epitomizes the balance between providing hope in a treatment while titrating the reality of a prognosis that is not curable. It requires giving reassurance while reminding the patient and family of the reality. SDM can help provide clinical decision transparency and ameliorate disappointments with limited treatment effectiveness.

“I Failed the Test”: The Unlucky Biology Club Member

Sarah was a 73-year-old patient with newly diagnosed non–small-cell lung cancer who had no actionable mutation. At her first visit, she was clutching an article from The New York Times and yelling, “I want the serial killer!” She had come to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in hopes of enrolling in a clinical trial with first-line immunotherapy. When she did not meet trial entry criteria because of her PD-L1 status, she became enraged at being denied the opportunity that she had heard and read about. The article she held on to described how immunotherapy unleashes a so-called serial killer that ravages all cancer cells in the body, which is understandably what she wanted.29

Sarah had delayed seeking cancer treatment in hopes of having the right mutation to enroll in a clinical trial. After some discussion about her particular type of cancer and her available treatment options, she was relieved. However, she was still angry because she did not receive this publicized treatment. The Unlucky Biology Club members feel that their tumor biology has conspired against them; they are angered by the treatment options that are available for others but not for them. They feel that it is not fair that other patients with the same cancer are treated with more desirable targeted therapies. This may resonate with failures in their life before having cancer.

It is crucial to validate their emotions of anger, fear, frustration, and worry by saying, “I can’t imagine what it has been like for you to hear this news; I can see this is very upsetting. Is it okay if we talk a bit more about what this means?” In this scenario, it is important to educate and reorient the patient who has been stuck on one idea as a result of their limited information. As part of SDM, the clinician should provide information on benefit and risk, such as, “This information helps us plan the very best treatment for you.” Clinicians should be careful about comparing patients and especially about providing unsolicited information.

This is an opportunity to re-establish/realign with the patient’s goals. “Given what you know about your illness, what’s most important to you?” Or, “As you think about the future, are there situations or things that you want to make sure you accomplish or avoid?” Explain that treatment options can be re-evaluated and tailored to the patient’s wishes. This may signal an opportunity to regain control of the situation. It also sends a positive message that although one opportunity for treatment did not work out, the team provides realistic hope and direction, despite a disappointment.

“A New Drug Has Just Come Out”: A Novel Treatment

Michael was a 47-year-old patient with sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, a rare form of head and neck cancer. He had aggressive metastatic disease. In the midst of his transition to hospice, a new drug for metastatic head and neck cancers, pembrolizumab, was approved. Although the drug had never been tested with his specific head and neck cancer, sinonasal undifferentiated carcinoma, his clinicians believed that he had to be informed about the new treatment because he was young and otherwise healthy and, if it worked, would possibly provide a durable response. The treating oncologist was presented with an ethical dilemma. He did not want to complicate or disrupt the decision to accept hospice care, yet he felt ethically bound to offer a treatment for which Michael had become eligible.

This case highlights an ethical dilemma associated with the interface of advancing science and clinical care. It illustrates how the emergence of rapidly changing oncology treatments begets new levels of uncertainty in the cancer experience (eg, no specific data for a cancer subtype, even though pembrolizumab had been approved for head and neck cancers). Clinicians are taught to provide answers, which can be frustrating when new data become available and raise new questions and more uncertainty (eg, does the drug work in this cancer subtype?). Medical training teaches clinicians how to handle uncertainty, but it does not teach them how to share its presence in a constructive way for patients.30

A full discussion was undertaken with the patient about the absence of data, the ethical reason for informing him of the new agent, and the inherent complications of considering another new treatment. He decided to stay with his decision to begin hospice care.

It is important to discuss patients’ emotions about clinical uncertainty and the various treatment options, framed in the context of their current clinical situation: “I realize this is all very complicated; let me try to explain these options in the setting of your illness.” This also functions to avoid abstract discussion and to evaluate real options according to SDM principles. Also, it is important to frequently determine their level of understanding (facilitates deliberation): “Can you tell me, in your words, what you understand?” Also, it is helpful to review the patient’s clinical information together as a background to discussing the uncertainty.

In situations of greatest clinical uncertainty, it is important to assure the patient that you are available for further discussion of their concerns and questions. A partnering statement, conveying the sense of “We’re in this together and I will continue to work with you,” is helpful to demonstrate a personal commitment to providing the best care possible despite the clinical uncertainty. Patients who feel that they are in a partnership with their clinicians are better able to trust them and tolerate clinical uncertainty.31

“I Know I Can Beat It”: The Denier

Don was a 68-year-old patient with progressive metastatic colon cancer who had received all conventional lines of cancer treatment. He still believed that the best treatment would cure his cancer. Don said that he was the exception, frequently finding ways to explain how the negative clinical facts did not apply to him. He made many references to newly available targeted therapies that he believed could be used to treat his cancer.

Hope is a critical component of coping, especially in a time of great need. However, it can also be overly used to avoid present realities. The challenge with the Denier is to acknowledge hope while encouraging frank discussions regarding prognosis. Offering tumor genome sequencing and potential enrollment in a basket trial, for example, or off-label drug use provides an extended amount of hope. These offers are often made in the face of overwhelming disease biology. For most advanced cancers, precision oncology finds driver mutations in only a minority of cases, and the goal of most early trial design is still safety and not necessarily efficacy. These are difficult concepts to explain to patients who will probably only hear that there is hope.

Typically, educating the Denier will require revisiting the topic several times to try to arrive at a shared understanding of the actual situation: “You may be eligible for a trial if your cancer has a certain mutation; however, taking the drug in this basket trial may not extend your life.” When the patient’s condition worsens, the education may have to become more pointed: “Scans don’t always reflect what is going on in terms of tumor growth” and “A change in functional status is an indication that the cancer is progressing.” In the context of denial, it is helpful to acknowledge the patient’s and caregiver’s values. “I hear you saying that what is most important to you is…” and “I understand that you want to make sure to avoid the following…” This demonstrates that they have been heard, ensures that the goal of hope is not being taken away, and helps the patient to evaluate options. It is also important to keep in mind that the Denier fluctuates in their level of denial and may partially accept the reality of the situation. Patients often maintain two levels of awareness and acknowledgment of the situation. One is cognitive: “I know how ill I am.” The other is emotional: “I simply can’t believe I could die.” Both exist simultaneously in many patients, which accounts for these day-to-day attitudinal changes. An ongoing positive clinician-patient relationship allows these feelings to emerge, and a more realistic discussion can occur about end-of-life planning, for example. A focus on maintaining high quality in the clinician-patient relationship is a key to facilitating SDM. Often, a patient’s underlying fear will ameliorate in the context of working closely together.

“I Have Done My Research”: The Overly or Misinformed Patient

Barbara was a 49-year-old well-educated professional with non–small-cell lung cancer metastatic to brain and bone. Molecular studies revealed that her tumor DNA harbored a BRCA2 mutation. She was very excited to start using olaparib, which she had heard could be used to target BRCA2 mutations. Barbara had strong opinions about the new treatment choices for lung cancer and was unwilling to consider therapies that were more appropriate for her type of disease.

This case illustrates the complexity of precision oncology and the level of sophisticated genomic knowledge that is required to have a fully informed conversation with a patient. After listening to her enthusiasm and concerns, the oncologist invited the patient to have a discussion about interpreting the genomic data of her tumor. She explained the difference between inherited DNA mutations, for which olaparib could be used in the presence of an inherited BRCA2 mutation in ovarian cancer, and the more common somatic mutations present in noninherited cancers such as her BRCA2-mutated non–small-cell lung cancer. After checking her understanding of the underlying principle, the oncologist provided a reasonable alternative treatment.

The ability to gather disease-specific information from the Internet and other sources has grown exponentially, and patients are armed with information that may help or hinder the treatment decision process.18 An abundance of data may be gathered as a means to produce a sense of personal control over the cancer and to enhance self-efficacy.16 Information gathering is comforting for some patients by helping them to plan next steps, but it may also help them to avoid facing reality. Many cancer-related Web sites have limited information about survival or treatment efficacy, which may lead to an overly optimistic or pessimistic view of survival.18 They are particularly limited in terms of providing adequate background information about genomic-based therapies. The complex molecular information is often not described in patient-friendly language and also runs the risk of being oversimplified. In this situation, correcting misinformation and misunderstanding is essential: “There are many exciting cancer treatments, but what’s important is that we find the right one for you.”

Some patients want all available information and want to actively participate in their treatment decision. Others might say, “I will leave it up to you to choose the best treatment.” It is important to figure out how much involvement the patient wants. Also, uncovering each patient’s major concerns is critical: “What information would be most helpful for me to know about you?” Then, it is important to acknowledge the patient’s concerns: “This must be very upsetting for you. It sounds like it’s important for you to be actively engaged in decision making. Let’s work together to come up with a plan that is best for you.” This acknowledges the importance of alliance.32

A request for a specific cancer treatment may be driven by an attempt to reach a goal, which may be modifiable in certain cases. It is crucial to demonstrate that you clearly understand their request: “I hear you saying that what’s most important is to continue treating your cancer to ensure you can reach your goal.”

Case Continued:

A rebiopsy after progression revealed a HER2 mutation that made her eligible for a basket trial.

The oncologist invited another discussion of her tumor DNA mutations and informed her that a newly found HER2 mutation would qualify her for a basket trial. The previous genomics discussion on inherited and somatic mutations helped her understand that she would be treated with a group of patients with different cancers, who would all have the same somatic tumor DNA mutation, to assess safety and perhaps efficacy in accordance with the trial objectives. She understood alternative treatment options and was offered a decision delay to facilitate deliberation and decision making. She was happy to receive more information about the basket trial, and the oncologist made sure that she understood the scientific rationale behind the study.

DISCUSSION: COMMUNICATION OF UNCERTAINTY IN PRECISION MEDICINE ONCOLOGY

Precision medicine and genomic information inform patient care in oncology. The psychosocial effects of these cancer treatments have yet to be adequately described and explored. So far, the literature remains limited.7,33,34 Patients acknowledge the promise of precision medicine but also consistently raise concerns about the discovery of incidental findings, information overload, complications from additional biopsies with delay in definitive cancer treatment, and the lack of a clear benefit.35

The risk of ineffective communication is that patients misunderstand the nature and seriousness of their diseases, which may lead to more aggressive and futile cancer treatments at the end of life or to increased fear and anxiety, while increasing stress and burnout in members of the medical team.36 On the other hand, effective communication enhances shared decision making, decreases patient distress, and increases patient satisfaction and trust in the medical team.25

Shared decision making is the communication style that is preferred by most patients.37 Patients make choices that are guided by the clinician’s information and recommendations. Patients may also have preferences on a spectrum of communication styles that can range from paternalistic (ie, the patient is a passive recipient of their care) to the clinician who is a nondirective information provider or educator (ie, the patient is given choices and decides on management according to his/her preferences).30 It can be helpful to simply ask how the patient and family would like to make decisions, and the clinician can discuss this spectrum to gain clarification. Another way to obtain a patient’s communication preferences is by taking a moment to elicit what the patient believes is different about him/herself. This is an effective way to uncover hidden concerns: “What do I need to know about you to give you the best care possible?”38 Knowledge of these personal details allows for effective therapeutic communication and treatment planning.

The provision of understandable information protects patient autonomy and enhances this ideal communication style of SDM. Discussing therapeutic uncertainty is often a difficult task for clinicians and leads to clinician behaviors of not disclosing all of the information, not talking about it, or oversimplifying the information.30 Understandably, this can leave patients with a distorted account of their clinical situation. They may make sense of the situation by prescribing to alternative explanations or hopes, introducing so-called extramedical values, or seeking other remedies (eg, alternative treatments) when presented with clinical uncertainty.30

The idea of effective disclosure has been proposed as a potential goal in discussing uncertainty with patients. This idea supposes that patients can tolerate a certain amount of uncertainty and that extra vigilance is required by the clinician to ensure that they are given the tools and information they need to engage in decision making.30 Effectively, extra care is taken in those situations of greater uncertainty to provide information and to ensure that the patient understands. This protects autonomy and increases patient trust in the long run.

Also, addressing underlying emotions, hopes, and fears is an effective way to ensure good communication and informed consent. A conversation analysis found that patients who are more assertive draw more empathy from their oncologists, whereas passive patients elicited much less emotional reciprocation from the oncologists.39 Clinicians may use open-ended questions, such as, “I’d like to switch gears and check in to see how you are feeling about all of this technical information?” or more closed-ended questions, such as, “Many patients may feel overwhelmed by all of the scientific information we’ve discussed; I’m wondering if that is true for you?” In addition, checking understanding and emotional reactions enhances the clinician-patient relationship and is key in the setting of uncertainty.

Directly focusing on the therapeutic aspects of the relationship—by assessing communication preference, checking understanding, and searching for underlying emotional issues—develops rapport and may bolster patients’ resilience in the face of clinical uncertainty. The clinician may say something such as: “I’m wondering if there is anything that might be difficult for you to discuss with me?” “Is there anything that I might be able to do to make this better for you?” or “I have a sense that you are someone who likes x, y, and z; please help me understand if I am correct.” “I’m wondering if there are other ways that you would like me to provide information for you.” Realigning goals may be accomplished by saying something such as: “It is my goal to provide you with the best information for us to make a decision that works for you; please let me know if that is also your goal or if you’d like to focus on additional issues.”

This human connection dimension of medical care is needed to withstand the uncertainty. Clinicians frequently underestimate the therapeutic power of their relationships with patients.40 A strong therapeutic bond is fundamental, not simply useful.41 Patients have varying abilities to trust, hope, and have faith in their clinicians. The relationship is strengthened by focusing on agreed-upon common goals and tasks.32 It is always appropriate to discuss the nuts and bolts of the therapeutic relationship, especially when the clinician perceives that it may not be firmly established or upon entering areas of clinical uncertainty that are inherent in the precision medicine era.

SUMMARY

Precision medicine presents a new era of communication in oncology. Many of the challenges are unique and need to be more thoroughly explored; however, the requisite communication approaches are drawn from basic communication principles such as SDM. This article has presented some of the common patient reactions to precision medicine and basic communication issues in oncology.

Communication can be used to enhance rapport, trust, and support. In the context of uncertainty, a study done in the 1980s asked patients their reasons for accepting a new chemotherapy drug in a clinical trial. Their answers were simple: “I hoped it might help”; “I was afraid if I did nothing”; and “I trusted my oncologist.”42 Hope and fear persist, but it is the last response that holds the key for the future: Communication that leads the patient to feel that the physician understands and cares about the patient as a person.43

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Daniel C. McFarland, Elizabeth Blackler, Jimmie Holland

Financial support: Daniel C. McFarland

Administrative support: Daniel C. McFarland

Provision of study material or patients: Daniel C. McFarland

Collection and assembly of data: Daniel C. McFarland

Data analysis and interpretation: Daniel C. McFarland, Elizabeth Blackler, Smita Banerjee

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS’ DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Communicating About Precision Oncology

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO’s conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or po.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Daniel C. McFarland

No relationship to disclose

Elizabeth Blackler

No relationship to disclose

Smita Banerjee

No relationship to disclose

Jimmie Holland

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th Ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorne SE, Oliffe JL, Oglov V, et al. Communication challenges for chronic metastatic cancer in an era of novel therapeutics. Qual Health Res. 2013;23:863–875. doi: 10.1177/1049732313483926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roychowdhury S, Chinnaiyan AM. Translating cancer genomes and transcriptomes for precision oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:75–88. doi: 10.3322/caac.21329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ashley EA. Towards precision medicine. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17:507–522. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mardis ER. A decade’s perspective on DNA sequencing technology. Nature. 2011;470:198–203. doi: 10.1038/nature09796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson SE, Chester JD. Personalised cancer medicine. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:262–266. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parodi S, Riccardi G, Castagnino N, et al. Systems medicine in oncology: Signaling network modeling and new-generation decision-support systems. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1386:181–219. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3283-2_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Elenee Argentinis JD, Weber G. IBM Watson: How cognitive computing can be applied to big data challenges in life sciences research. Clin Ther. 2016;38:688–701. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sledge GW, Jr, Miller RS, Hauser R. CancerLinQ and the future of cancer care. Am Soc Clin Oncol Ed Book. 2013:430–434. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams J, Conley B, Mooney M, et al. National Cancer Institute’s Precision Medicine Initiatives for the new National Clinical Trials Network. Am Soc Clin Oncol Ed Book. 2014:71–76. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2014.34.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biankin AV, Piantadosi S, Hollingsworth SJ. Patient-centric trials for therapeutic development in precision oncology. Nature. 2015;526:361–370. doi: 10.1038/nature15819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawler M, Kaplan R, Wilson RH, et al. Changing the paradigm—Multistage multiarm randomized trials and stratified cancer medicine. Oncologist. 2015;20:849–851. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moy B, Jagsi R, Gaynor RB, et al. The impact of industry on oncology research and practice. Am Soc Clin Oncol Ed Book. 2015:130–137. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2015.35.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis MA, Dicker AP. Social media and oncology: The past, present, and future of electronic communication between physician and patient. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:764–771. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMullan M. Patients using the Internet to obtain health information: How this affects the patient-health professional relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;63:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surbone A, Zwitter M, Rajer M, et al., editors. New Challenges in Communication with Cancer Patients. Berlin, Germany; Springer: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chik I, Smith TJ. Obtaining helpful information from the Internet about prognosis in advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:327–331. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.004739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulter A. Paternalism or partnership? Patients have grown up—and there’s no going back. BMJ. 1999;319:719–720. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7212.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: Online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333:417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1361–1367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein RM, Alper BS, Quill TE. Communicating evidence for participatory decision making. JAMA. 2004;291:2359–2366. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.19.2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coulter A. Do patients want a choice and does it work? BMJ. 2010;341:c4989. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—Pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:780–781. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zachariae R, Pedersen CG, Jensen AB, et al. Association of perceived physician communication style with patient satisfaction, distress, cancer-related self-efficacy, and perceived control over the disease. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:658–665. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, et al. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1242–1247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. Six Steps of Shared Decision Making. 2012.

- 29. Pollack A: Setting the body’s ‘serial killers’ loose on cancer. The New York Times, August 1, 2016:A1-A3.

- 30.Parascandola M, Hawkins J, Danis M. Patient autonomy and the challenge of clinical uncertainty. Kennedy Inst Ethics J. 2002;12:245–264. doi: 10.1353/ken.2002.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora NK. Interacting with cancer patients: The significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:791–806. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meystre C, Bourquin C, Despland JN, et al. Working alliance in communication skills training for oncology clinicians: A controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90:233–238. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McFarland DC. Putting the “person” in personalized cancer medicine: A systematic review of psychological aspects of targeted therapy. Personalized Medicine in Oncology. 2014;3:438–447. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanchette PS, Spreafico A, Miller FA, et al. Genomic testing in cancer: Patient knowledge, attitudes, and expectations. Cancer. 2014;120:3066–3073. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gray SW, Hicks-Courant K, Lathan CS, et al. Attitudes of patients with cancer about personalized medicine and somatic genetic testing. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:329–335. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2012.000626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thorne SE, Bultz BD, Baile WF, et al. Is there a cost to poor communication in cancer care? A critical review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2005;14:875–884; discussion 885-876. doi: 10.1002/pon.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Politi MC, Studts JL, Hayslip JW. Shared decision making in oncology practice: What do oncologists need to know? Oncologist. 2012;17:91–100. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chochinov HM, McClement S, Hack T, et al. Eliciting personhood within clinical practice: Effects on patients, families, and health care providers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49:974–980 e972. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.11.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beach WA, Dozier DM. Fears, uncertainties, and hopes: Patient-initiated actions and doctors’ responses during oncology interviews. J Health Commun. 2015;20:1243–1254. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kenny DA, Veldhuijzen W, Weijden Tv, et al. Interpersonal perception in the context of doctor-patient relationships: A dyadic analysis of doctor-patient communication. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70:763–768. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bordin ES: The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance Psychotherapy 16252–260.1979 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, et al. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: Patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:849–855. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1984.2.7.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peabody FW. The care of the patient. JAMA. 2015;313:1868. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]