Abstract

Objective

During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, suicidal behaviors increased among U.S. Army soldiers. Although Reserve Component (RC) soldiers (National Guard and Army Reserve) comprise approximately one third of those deployed in support of the wars, few studies have examined suicidal behaviors among these “citizen-soldiers”. The objective of this study is to examine suicide attempt risk factors and timing among RC enlisted soldiers.

Methods

This longitudinal, retrospective cohort study used individual-level person-month records from Army and Department of Defense administrative data systems to examine socio-demographic, service-related, and mental health predictors of medically documented suicide attempts among enlisted RC soldiers during deployment from 2004–2009. Data were analyzed using discrete-time survival models.

Results

A total of 230 enlisted RC soldiers attempted suicide. Overall, the in-theater suicide attempt rate among RC soldiers was 81/100,000 person-years. Risk was highest in the fifth month of deployment (13.76 per 100,000 person-months). Suicide attempts were more likely among soldiers who were women (adjusted odds ratio, aOR=2.5 [95% CI: 1.8–3.5]), less than high school educated (aOR=1.8 [95% CI: 1.3–2.5]), in their first two years of service (aOR=2.0 [95% CI: 1.2–3.4]), were currently married (aOR=2.0 [95% CI: 1.5–2.7], and had received a mental health diagnosis in the previous month (aOR= 24.7 [95% CI: 17.4–35.0]).

Conclusions

Being female, early in service and currently married are associated with increased odds of suicide attempt in RC soldiers. Risk of suicide attempt was greatest at mid deployment. These predictors and the timing of suicide attempt for RC soldiers in-theater is largely consistent with those of deployed Active Component (Regular) soldiers. Results also reinforce and replicate the findings among Active Component soldiers related to the importance of a recent mental health diagnosis and the mid-deployment as a period of enhanced risk.

Keywords: suicide attempt, suicide, deployment, military, Army, Army National Guard, Army Reserve, Reserve Component

Introduction

The standardized U.S. Army suicide rate has historically been below the comparable civilian rate. However, this rate increased substantially with the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and surpassed the civilian rate in 2008 (Brooks, Corrigan, Toussaint, & Pecko, 2018). Although the Army’s suicide rate declined slightly following its peak in 2012, it continues to be higher than the adjusted general population rate (Brooks et al., 2018; DoDSER, 2017). In response, research on suicide ideation, attempts, and deaths among soldiers has increased substantially (e.g., Naifeh, Mash, et al., 2019). The majority of this research has focused on the full-time soldiers that serve in the Army’s Active Component (AC; Regular Army), leaving comparatively less known about suicide risk among the “citizen-soldiers” of the Reserve Components (RCs), which consist of the U.S. Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve. Given the intermittent nature of RC service, it is difficult to examine the RC at any given time. However, since deployment is generally a continuous period of active service that only ends with return home, this time provides a unique opportunity to examine documented suicide attempts among RC soldiers using the Army’s administrative data systems.

The RCs augment the AC when federalized (e.g., activated at times of war and national emergencies) and represent just over half of the total active and inactive Army (DoD, 2018). When not federally activated (e.g., when not deployed in support of combat operations), the vast majority of RC soldiers live in communities across all U.S. states and territories, pursuing civilian careers or education, while participating in intermittent military training (10 USC Ch. 1601). When federalized onto active duty, these soldiers operate as those in the AC and experience similar deployment-related stressors (e.g., separation from family, combat) (Milliken, Auchterlonie, & Hoge, 2007). The RCs’ size and roles, as well as their responsibilities in global operations, have changed over time based on the needs of the Army (additional information available at www.nationalguard.com and www.usar.army.mil). More than one third of soldiers deployed between 2001 and 2015 were from the RCs (Wenger, O’Connell, & Cottrell, 2018), a substantially greater federalization of RC soldiers than in the time prior to the Afghanistan and Iraq wars (Bonds, Baiocchi, & L.L., 2010).

The majority of research on deployment-related mental health outcomes among RC soldiers is based on self-report surveys administered post-deployment (e.g., Calabrese et al., 2011; Cohen et al., 2017; Kline, Ciccone, Falca-Dodson, Black, & Losonczy, 2011). Few mental health studies have examined the administrative medical records of RC soldiers during deployment (Reger et al., 2015). Unlike AC soldiers who remain on active duty, the health records of those in the RCs are not fully captured by the Army’s administrative data systems because of their intermittent services. For AC soldiers, the rates of documented suicide attempts are lower during deployment than among soldiers who have never deployed or are previously deployed (Naifeh, Ursano, et al., 2019; Ursano et al., 2016). Importantly, because deployment is a continuous time of service for RC soldiers, it provides an opportunity to examine predictors of RC suicide risk and compare it to that of the AC. Improved understanding of risk among RC soldiers in-theater may inform intervention strategies aimed at reducing suicidal behaviors during and after deployment.

Within the total activated RC population from 2004–2009, including those never deployed, currently deployed, and previously deployed, enlisted RC soldiers account for nearly 96% of documented suicide attempts, with officers accounting for the remaining 4% (Naifeh, Ursano, et al., 2019). The odds of suicide attempt were higher for those who were female, younger, white, less educated, married, in the first 2 years of active Army service, and diagnosed with a mental health disorder (Naifeh, Ursano, et al., 2019). It is not known if the same risk factors are associated with suicide attempts during deployment.

In the current study, we used 2004–2009 administrative data from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) (Ursano et al., 2014) to examine the association of socio-demographic, service-related, and mental health factors with documented suicide attempts among enlisted RC soldiers during deployment. In addition we examined the timing of suicide attempt risk, which research among AC soldiers suggests is highest at mid-deployment (Ursano et al., 2016).

Materials and methods

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of the Uniformed Services University, the University of California, Dan Diego, Harvard Medical School, and the University of Michigan Institute for Social Research.

Sample

The Historical Administrative Data Study (HADS) is a component of Army STARRS that integrates individual-level deidentified records from 38 Army and Department of Defense administrative data systems for all soldiers on active duty between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2009 (Kessler et al., 2013). This includes 743,171 RC soldiers (i.e., U.S. Army National Guard and U.S. Army Reserve) who were federally activated in support of Operations Enduring Freedom, Iraqi Freedom, and New Dawn for more than 30 days under Title 10. The current longitudinal, retrospective cohort study focuses on person-month records for all enlisted RC soldiers who were deployed (i.e., in-theater) when they made a documented suicide attempt (n=230 soldiers) and a 1:200 sample of all other enlisted RC soldiers in-theater (n=16,967 control person-months). Prior to selection, control person-months were stratified by sex, rank, time in service, deployment status, and historical time. Person-month data were analyzed using discrete-time survival framework (Willett & Singer, 1993), with each month in a soldier’s career treated as a separate observational record. To adjust for under-sampling, control person-months were weighted to 200. When control person-months are randomly subsampled and weighted, unbiased discrete-time survival coefficients can be estimated (Schlesselman, 1982).

Measures

Suicide attempts were identified using Department of Defense Suicide Event Report (DoDSER) records and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnostic codes from healthcare encounter data systems including The Military Health System Data Repository, Theater Medical Data Store, and TRANSCOM (Transportation Command) Regulating and Command and Control Evacuating System (sTable 1). Healthcare encounter records with a documented E950-E958 ICD-9-CM code were used to identify cases with a self-inflicted poisoning or injury with suicidal intent. The E959 code, indicating late effects of a self-inflicted injury, was excluded as it confounds the temporal associations between predictors and suicide attempt (Walkup, Townsend, Crystal, & Olfson, 2012). Records were cross-referenced between data systems to ensure that all cases of suicide attempt represented unique soldiers. In the event that multiple suicide attempts were documented for a single soldier, a hierarchical classification scheme was used to select the first attempt (Ursano et al., 2015). The control sample excluded person-months in which there was documented non-fatal suicidal behavior (Ursano et al., 2015) or death due to suicide, combat, homicide, injury or illness.

Administrative records were used to construct variables for socio-demographic characteristics (gender, age at entry into Army service, current age, race, education, and marital status), active time in service (the number of months a RC soldier was activated), months into current deployment, number of deployments, and presence/recency of mental health diagnosis. Mental health diagnoses were identified using ICD-9-CM mental disorder codes (sTable 2), excluding postconcussion syndrome, tobacco use disorder, and supplemental V-codes that are not disorders such as marital problems or stressors. Recency of mental health diagnosis was determined by calculating the number of months between the most recently recorded diagnosis and the subsequent suicide attempt (cases) or sampled person-month record (controls).

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute 2013). Discrete-time person-months survival analysis with a logit link function was used to examine univariable associations of socio-demographic characteristics with suicide attempt. This was followed by a series of multivariable models (adjusting for socio-demographics and active time in service) that separately examined the incremental predictive effects of previous mental health diagnosis, and months into current deployment. To examine the potential influence of deployment history, each final model was estimated again while controlling for number of deployments (currently on first deployment vs. second or greater). Odds-ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained by exponentiating the logistic regression coefficients. Using the coefficients from the final model, we generated a standardized risk estimate (SRE) (Roalfe, Holder, & Wilson, 2008) for each predictor category, expressed as the number of suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years. The SREs assume other predictors in the final model are at their sample-wide means. All logistic regression models included a dummy variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends in suicidal behaviors during the study period (Black, Gallaway, Bell, & Ritchie, 2011; DoA, 2012; Schoenbaum et al., 2014; Ursano et al., 2015; Ursano, Naifeh, et al., 2018).

To examine the risk of suicide attempt as a function of time in theater, we used discrete-time survival models that estimated risk (suicide attempters per 100,000 person-months) in each active month in theater) and linear spline models. Analyses estimated risk by month into current deployment among those who were on their first deployment. Splines (piecewise linear functions) were calculated based on the hazard rates to assess changes in risk by time in theater. After fitting a linear function to the data, χ2 tests, deviance, and the Akaike Information Criterion were used to test whether knots and additional linear segments improved model fit and to assess nonlinearities in changes in risk by time in theater.

Results

Our sample of deployed enlisted RC soldiers was primarily male (89.8%), older (32.9% above the age of 34), non-Hispanic white (70.3%), and high school educated (earned a high school diploma) (72.9%). Approximately half were never married (48.7%), and similarly nearly half were currently married (47.3%) (Table 1). Of the 230 soldiers who attempted suicide, 78.7% were male, 69.1% were younger than 30 years, 70.4% were non-Hispanic white, 67.4% were high school educated, and 52.6% were currently married. Overall, the in-theater suicide attempt rate was 81/100,000 person-years. Univariable models (Table 1) show that odds of suicide attempt were elevated for females (OR=2.4 [95% CI: 1.7–3.2]) and those who were less than high school educated (OR=2.0 [95% CI: 1.5–2.8]). Odds were lower among soldiers who were over the age of 40 (OR=0.4 [95% CI: 0.2–0.7]) when compared to soldiers who were 30–34. Compared to soldiers in their fifth to tenth year of active service, those in their first two years were almost twice as likely to have a documented suicide attempt and soldiers in their 11th year or greater were less likely to have a documented suicide attempt (OR=1.7 [95% CI: 1.2–2.4], OR=0.5 [95% CI: 0.3–0.8] respectively).

Table 1.

Univariable and Multivariable Associations of Socio-demographic Characteristics and Active Time in Service with Suicide Attempt Among Deployed Enlisted Soldiers in the U.S. Army Reserve Components.1

| Univariable Analyses2 | Multivariable Analysis3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | aOR | (95% CI) | Cases (N) | Total (N)4 | Rate5 | Pop %6 | SRE7 | |

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 181 | 3,047,781 | 71.3 | 89.8 | 71 |

| Female | 2.4* | (1.7–3.2) | 2.5* | (1.8–3.5) | 49 | 345,849 | 170.0 | 10.2 | 178 |

| χ21 | 28.2* | 29.9* | |||||||

| Age at Army Entry (years) | |||||||||

| < 21 | 1.1 | (0.7–1.5) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | 173 | 2,548,173 | 81.5 | 75.1 | 88 |

| 21–24 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 35 | 527,235 | 79.7 | 15.5 | 72 |

| ≥ 25 | 1.0 | (0.6–1.7) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.5) | 22 | 318,222 | 83.0 | 9.4 | 58 |

| χ22 | 0.1 | 1.8 | |||||||

| Current Age (years) | |||||||||

| < 21 | 1.6 | (1.0–2.6) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.9) | 34 | 291,634 | 139.9 | 8.6 | 94 |

| 21–24 | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.3) | 69 | 848,669 | 97.6 | 25.0 | 72 |

| 25–29 | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.5) | 56 | 695,856 | 96.6 | 20.5 | 89 |

| 30–34 | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 31 | 439,431 | 84.7 | 12.9 | 102 |

| 35–39 | 0.6 | (0.4–1.1) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.5) | 21 | 452,221 | 55.7 | 13.3 | 82 |

| ≥ 40 | 0.4* | (0.2–0.7) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.3) | 19 | 665,819 | 34.2 | 19.6 | 61 |

| χ25 | 29.3* | 4.5 | |||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 162 | 2,386,762 | 81.4 | 70.3 | 81 |

| Black | 1.1 | (0.7–1.5) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.6) | 35 | 494,235 | 85.0 | 14.6 | 90 |

| Hispanic | 1.0 | (0.6–1.6) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.6) | 21 | 301,821 | 83.5 | 8.9 | 81 |

| Asian | 0.7 | (0.3–1.5) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.6) | 7 | 141,607 | 59.3 | 4.2 | 60 |

| Other | 1.0 | (0.4–2.5) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.4) | 5 | 69,205 | 86.7 | 2.0 | 80 |

| χ24 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||||

| Education | |||||||||

| < High School8 | 2.0* | (1.5–2.8) | 1.8* | (1.3–2.5) | 54 | 405,654 | 159.7 | 12.0 | 136 |

| High School | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 155 | 2,473,755 | 75.2 | 72.9 | 74 |

| Some College | 0.7 | (0.3–1.4) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) | 8 | 188,808 | 50.8 | 5.6 | 58 |

| ≥ College | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.5) | 13 | 325,413 | 47.9 | 9.6 | 62 |

| χ23 | 26.2* | 15.8* | |||||||

| Marital Status | |||||||||

| Never Married | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 100 | 1,652,300 | 72.9 | 48.7 | 58 |

| Currently Married | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | 2.0* | (1.5–2.7) | 121 | 1,606,521 | 90.4 | 47.3 | 118 |

| Previously Married | 1.0 | (0.5–2.1) | 1.7 | (0.8–3.5) | 9 | 134,809 | 81.1 | 4.0 | 100 |

| χ22 | 2.5 | 21.6* | |||||||

| Active Time in Service9 | |||||||||

| 1–2 Years | 1.7* | (1.2–2.4) | 2.0* | (1.2–3.4) | 121 | 1,124,921 | 129.1 | 33.1 | 130 |

| 3–4 Years | 1.0 | (0.6–1.6) | 1.2 | (0.7–2.0) | 37 | 576,837 | 77.0 | 17.0 | 76 |

| 5–10 Years | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 38 | 613,638 | 74.3 | 18.1 | 64 |

| ≥ 11 Years | 0.5* | (0.3–0.8) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.3) | 34 | 1,078,234 | 37.8 | 31.8 | 42 |

| χ23 | 37.3* | 10.8* | |||||||

| Total | – | – | 230 | 3,393,630 | 81.3 | 100.0 | – | ||

Abbreviations: OR= Odds ratio, CI= Confidence Interval, aOR = adjusted odds ratio, SRE = standardized risk estimate

The sample of deployed Reserve Component enlisted soldiers (n=230 cases, 16,967 control person-months) is a subset of the total Reserve Component sample (n=70,970 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers Historical Administrative Data Study. All analyses included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Parameter estimates from weighted univariable analyses (i.e., each variable modeled separately with suicide attempt)

Parameter estimates were weighted and adjusted for gender, age at army entry, current age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, and active time in service

Total includes both cases (i.e., suicide attempters) and weighted control person-months.

Rate per 100,000 person-years, calculated based on n1/n2, where n1 is the unique number of soldiers within each category and n2 is the annual number of person-years, not person-months, in the population.

Pop% = Percent of the currently deployed Reserve Component enlisted population.

SRE = Standardized risk estimate (suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) calculated assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means.

<High School includes: General Educational Development credential (GED), home study diploma, occupational program certificate, correspondence school diploma, high school certificate of attendance, adult education diploma, and other non-traditional high school credentials.

Based on the number of months a soldier served on active duty (e.g., 1–2 years = 0–24 months of active service; 3–4 years = 25–48 months of active service, etc.).

p<0.05

In a multivariable model adjusting for socio-demographic variables and active time in service (Table 1), females were more than twice as likely as males to have a documented suicide attempt (aOR=2.5 [95% CI: 1.8–3.5]). Odds were also elevated among those who were less than high school educated (aOR=1.8 [95% CI: 1.3–2.5]), and in their first two years of active service (i.e., 0–24 active months) (aOR=2.0 [95% CI: 1.2–3.4]). In contrast to the univariable results, the odds of suicide attempt were two times higher among soldiers who were currently married (aOR=2.0 [95% CI: 1.5–2.7]) when compared to those who were never married. Standardized risk of suicide attempt was highest for females (SRE=178/100,000 person-years), those who were less than high school educated (SRE=136/100,000 person-years), and those in their first two active years of service (SRE=130/100,000 person-years) (Table 1).

Mental health diagnosis

Among deployed enlisted RC soldiers who attempted suicide, 40.9% had a previous mental health diagnosis compared to 8.3% of controls, (Table 2). Among suicide attempters with a history of mental health diagnosis, just under half (48.9%) had a diagnosis recorded in the month prior to their attempting suicide. Univariable models (Table 2) show that compared to soldiers with no mental health diagnosis, the odds of suicide attempt were highest among RC soldiers with a mental health diagnosis documented in the previous month (OR=27.4 [95% CI: 19.4–38.6]), with odds decreasing as time since most recent diagnosis increased (OR= 8.2 [95% CI: 5.0–13.5] for 2–3 months, OR= 5.1 [95% CI: 3.2–8.1] for 4–12 months). The odds of suicide attempt for most recent mental health diagnosis 13 or more months prior to suicide attempt decreased below the parameter estimate for 4–12 months, though the odds ratio did not reach statistical significance (p<0.05), (OR= 1.6 [95% CI: 0.8–3.2]).

Table 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Associations of Mental Health Diagnosis and Time in Deployment with Suicide Attempt Among Deployed Enlisted Soldiers in the U.S. Army Reserve Components.1

| Univariable Analyses2 | Multivariable Analyses3 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | aOR | (95% CI) | Cases (N) | Total (N)4 | Rate5 | Pop %6 | SRE7 | |

| I. Time Since Most Recent Mental Health Diagnosis | |||||||||

| No Diagnosis | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 136 | 3,112,736 | 52.4 | 91.7 | 52 |

| 1 Month | 27.4* | (19.4–38.6) | 24.7* | (17.4–35.0) | 46 | 35,246 | 1566.1 | 1.0 | 1,290 |

| 2–3 Months | 8.2* | (5.0–13.5) | 7.9* | (4.8–13.0) | 18 | 43,418 | 497.5 | 1.3 | 414 |

| 4–12 Months | 5.1* | (3.2–8.1) | 5.3* | (3.3–8.4) | 21 | 85,821 | 293.6 | 2.5 | 275 |

| ≥ 13 Months | 1.6 | (0.8–3.2) | 2.2* | (1.1–4.5) | 9 | 116,409 | 92.8 | 3.4 | 117 |

| χ24 | 394.2* | 353.4* | |||||||

|

II. Time in Deployment | |||||||||

| 1–3 Months | 1.0 | – | 1.0 | – | 50 | 964,850 | 62.2 | 28.4 | 61 |

| 4–6 Months | 1.7* | (1.2–2.4) | 1.7* | (1.2–2.5) | 82 | 867,082 | 113.5 | 25.6 | 106 |

| 7–9 Months | 1.4 | (0.9–2.0) | 1.5 | (1.0–2.1) | 55 | 749,655 | 88.0 | 22.1 | 89 |

| ≥ 10 Months | 1.0 | (0.7–1.6) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | 43 | 812,043 | 63.5 | 23.9 | 70 |

| χ23 | 12.7* | 11.0* | |||||||

Abbreviations: OR= Odds ratio, CI= Confidence Interval, aOR = adjusted odds ratio, SRE = standardized risk estimate

The sample of deployed Reserve Component enlisted soldiers (n=230 cases, 16,967 control person-months) is a subset of the total Reserve Component sample (n=70,970 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers Historical Administrative Data Study.

Parameter estimates from weighted univariable analyses (i.e., each variable modeled separately with suicide attempt)

Time since most recent mental health diagnosis and time in current deployment were examined in separate models that controlled for basic socio-demographic variables (gender, age at entry into the Army, current age, race, education, and marital status) and active time in service. All analyses also included a dummy predictor variable for calendar month and year to control for secular trends.

Total includes both cases (i.e., suicide attempters) and weighted control person-months.

Rate per 100,000 person-years, calculated based on n1/n2, where n1 is the unique number of soldiers within each category and n2 is the annual number of person-years, not person-months, in the population.

Pop% = Percent of the currently deployed Reserve Component enlisted population.

SRE = Standardized risk estimate (suicide attempters per 100,000 person-years) calculated assuming other predictors were at their sample-wide means.

p<0.05

In multivariable models adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics and active time in service, deployed RC soldiers with a mental health diagnosis in the previous month continued to have the highest odds of suicide attempt compared to those without a diagnosis (aOR= 24.7 [95% CI: 17.4–35.0]), with odds decreasing monotonically as time since most recent diagnosis increased (aOR= 7.9 [95% CI: 4.8–13.0] for 2–3 months to aOR= 2.2 [95% CI: 1.1–4.5] for 13 or more months). Similarly, standardized risk of suicide attempt was highest for soldiers diagnosed in the previous month (SRE=1,290/100,000 person-years) and decreased to 117/100,000 for soldiers 13 or more months since diagnosis. Standardized risk was lowest for those with no history of diagnosis (SRE=52/100,000 person-years), (Table 2).

Time in deployment

Somewhat more than one-third (35.7%) of soldiers who attempted suicide were 4–6 months into deployment, (Table 2). Univariable models presented in Table 2 show that compared to RC soldiers who are 1–3 months into their current deployment, the odds of suicide attempt were highest among those who were 4–6 months into their current deployment (OR=1.7 [95% CI: 1.2–2.4]). The odds of suicide attempt then decreased as time in current deployment increased, though parameter estimates (7–9 months or 10 or more months) were not significantly different from the 1–3 months’ time.

In the multivariable model adjusting for socio-demographic characteristics and active time in service, the odds of suicide attempt were almost two times higher for the 4–6 months into deployment group compared to those 1–3 months into deployment (aOR=1.7 [95% CI 1.2–2.5]). Similar to the univariable analyses, the odds of suicide attempt after the sixth month of deployment (7–9 months and 10 or more months), were not significantly different from 1–3 months. The standardized risk of suicide attempt was highest for soldiers who were four to six months into their deployment (SRE=106/100,000 person years), (Table 2).

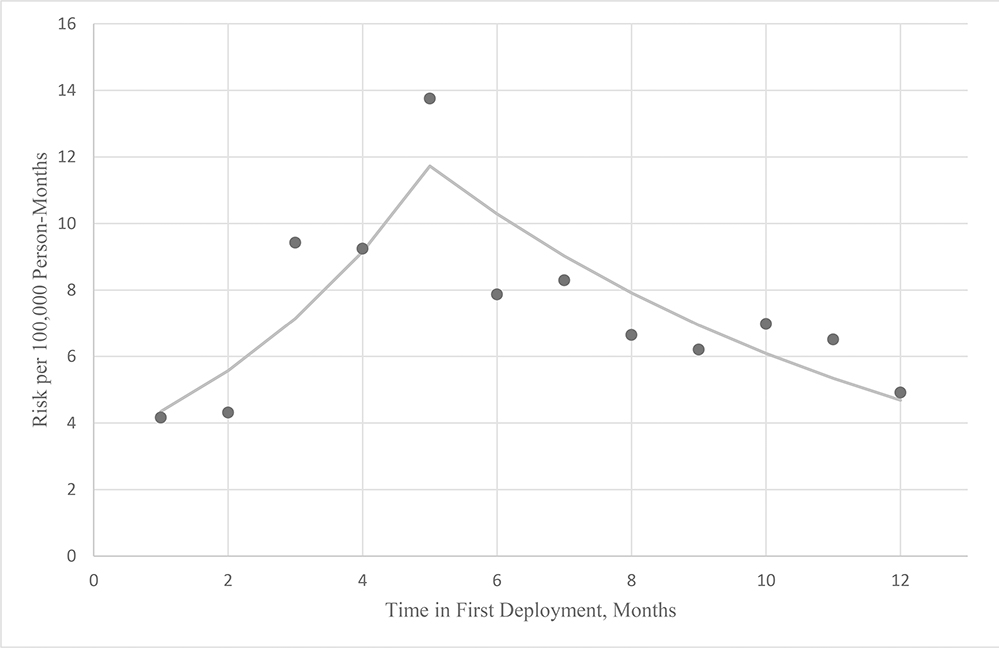

In order to examine the influence of time into deployment with more granularity, we used a discrete-time survival model to estimate suicide attempt risk in each active month in theater with linear spline models among those in their first deployment. Hazard functions indicated that RC soldiers in their first deployment were at greatest risk in their fifth month of deployment (13.76 per 100,000 person months), followed by a gradual decline in risk over the remaining months with slight fluctuations. Spline analyses indicate that adding a knot at the fifth month provided the best fit. Additional knots did not significantly improve model fit, suggesting that risk among currently deployed soldiers increases from the first to fifth month of deployment then declines gradually through the end of the first year (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Monthly Risk of Suicide Attempt Among Deployed Enlisted Soldiers in the U.S. Army Reserve Components On Their First Deployment1

1The sample of deployed Reserve Component enlisted soldiers in their first deployment n=13,871 is a subset of the total Reserve Component sample (n=70,970 person-months) from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers Historical Administrative Data Study.

Previous deployment history

In consideration of research indicating that risk for adverse mental health outcomes is lower among soldiers selected to deploy multiple times (i.e., the “healthy warrior effect”) (Hoge, Auchterlonie, & Milliken, 2006; Ireland, Kress, & Frost, 2012), we repeated the previous multivariable analyses with an additional variable indicating whether soldiers were in their first deployment. Among those who attempted suicide, 87.0% were in their first deployment. RC soldiers in their first deployment were 60% more likely to have a documented suicide attempt compared to those who had previously deployed (OR=1.6 [95% CI: 1.0–2.4]). Inclusion of deployment history as an additional control variable for the all final models did not alter the significance, direction, or substantial magnitude of parameter estimates (sTable3 & sTable4).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first RC study examining medically documented suicide attempts in-theater during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. The rate of suicide attempt for deployed enlisted RC soldiers was lower than the overall rate for the total enlisted RCs on active duty (81/100,000 person-years vs 108/100,000 person years) (Naifeh, Ursano, et al., 2019). The lower rate during deployment is consistent with findings for enlisted AC soldiers where the rate of suicide attempt is lowest during deployment compared to never deployed and previously deployed (Ursano et al., 2016).

Importantly, our sample of deployed enlisted RC soldiers had a lower rate of suicide attempt than deployed enlisted AC soldiers, (81/100,000 person-years vs 157/100,000 person-years) (Ursano et al., 2016). This substantially lower attempt rate may be attributed to several possibilities. It is possible that RC soldiers with suicidal thoughts or other mental health symptoms associated with suicide attempts are less likely to be federalized into active duty as well as less likely to deploy. Additionally, previous studies have consistently identified that younger soldiers are at an elevated risk of suicidal behaviors during and after deployment (Schoenbaum et al., 2014; Ursano et al., 2015). Our sample of deployed enlisted RC soldiers represents a slightly older group compared to those in the AC. For instance, 32.9% of our sample is aged 35 and above whereas in the deployed enlisted AC, only 14.3% were within this age group (Ursano et al., 2016). Similarly, looking within a younger strata, 33.6% of our sample is aged 24 and below compared to nearly 50% of deployed enlisted AC soldiers (Ursano et al., 2016).

Female gender, being less educated, in active service for two years or less, and being currently married (vs. never married) were associated with increased odds of suicide attempt among deployed enlisted RC soldiers. These risk factors of suicide attempt replicate the findings of a previous study which examined deployed enlisted AC soldiers (Ursano et al., 2016). The elevated risk among females, which is commonly observed in other populations (Fox, Millner, Mukerji, & Nock, 2018), highlights the potential role of gender differences in interpersonal and occupational stressors experienced before and during deployment (e.g., sexual abuse and assault, harassment and discrimination, types of combat experiences, and level of social support) (Street, Vogt, & Dutra, 2009). Understanding risk among female soldiers is a particularly important target for future research given evidence that there is a substantially greater relative rise in suicide among women than men during deployment (Street et al., 2015). Interestingly, our finding of current marital status as a risk factor for suicide attempt is consistent between the two components suggesting that future studies should further examine this relationship. For example, suicide attempt risk in the enlisted AC population varies by recency of marriage (Ursano, Kessler, et al., 2018b), but this has yet to be examined among RC soldiers. Given that interpersonal connection may be an important factor in suicide risk (Joiner, 2005), deployed soldiers may benefit from interventions that help protect marriages from the disruption of a deployment (McNulty, Olson, & Joiner, 2019). Though moderate differences in odds were identified for racial minorities among AC soldiers (Ursano et al. 2016), these relationships were not statistically significant among our sample of deployed enlisted RC soldiers, despite similar racial distributions between the two.

The association between history of mental health diagnosis and suicide attempt observed in this study is not surprising given that the relationship between psychiatric disorders and suicidal behaviors has been well established in the general population (Harris & Barraclough, 1997) as well as within the U.S. Army (Millner et al., 2017; Nock et al., 2014; Nock et al., 2015). Importantly, the patterns observed here (i.e., the odds of suicide attempt increase in magnitude the more recent the diagnosis) are consistent with those observed among deployed AC soldiers (Ursano et al., 2016). This consistency provides evidence for the importance of the risk associated with the time after a mental health visit. Efforts to detect and intervene with soldiers at risk of suicidal behavior may benefit from a more detailed examination of the risk associated with specific mental health diagnoses (e.g., major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder) or diagnostic categories (e.g., mood disorders, anxiety disorders). Importantly, 51.9% of suicide attempters in our sample did not have an administratively documented mental health diagnosis indicating they were not noted to have had any mental health problems by their Army medical records. This proportion is 34.1% larger than that among deployed enlisted AC soldiers where 38.7% of suicide attempters were without an administratively documented mental health diagnosis prior to attempt (Ursano et al., 2016). The larger proportion observed in our sample of deployed enlisted RC soldiers is possibly a function of the limited amount of time administrative data is captured among them, highlighting the challenges in identifying those at risk. Understanding risk among those without an administratively documented mental health diagnosis is important for soldiers in both the RC and AC (Ursano, Kessler, et al., 2018a).

The rate of suicide attempt peaked approximately mid-deployment at five months in-theater then gradually declined through the end of the soldier’s first year. This is similar to our previous findings among deployed enlisted AC soldiers where the risk of suicide attempt was highest in the sixth month of deployment (Ursano et al., 2016). A similar curvilinear relationship between month in theater and suicide and suicide ideation was observed in early Army reports where risk peaked around mid-deployment (MHAT-V, 2008). The consistency of this pattern indicates the importance of further understanding this phase of deployment and suggests that preventive interventions targeted to the high-risk period of mid-deployment may benefit all soldiers, regardless of component.

The odds of suicide attempt were significantly higher among the 80.6% of soldiers on their first deployment. Evidence suggests that soldiers selected to deploy have decreased mental health and suicide risk relative to those who have not yet deployed (Kline et al., 2010), resulting in what is often referred to as the “healthy warrior effect” (Hoge et al., 2006; Ireland et al., 2012; Larson, Highfill-McRoy, & Booth-Kewley, 2008). Our findings indicate there may be a similar selection effect when comparing those with multiple deployments to those on their first deployment, although evidence for this is inconsistent (Kline et al., 2010). Soldiers who deploy multiple times are generally older, have served in the Army for a longer period of time, and have been selected based on successfully completing a first deployment, all of which are factors that may be protective. Despite the importance of deployment history, the current study found that all risk factors identified for suicide attempt among RC soldiers during deployment remained significant even after accounting for previous deployments.

This study is not without limitations. First, administratively recorded suicide attempts are limited to events captured by the healthcare system. These records are subject to errors in coding and clinical judgment. Second, the data are limited to person-months during which individual RC soldiers were federally activated. However, during deployment this is expected to be a continuous period of federal activation. Finally, findings represent deployed RC soldiers during 2004–2009 and may not generalize to other time periods or other branches of the military.

Conclusion

Risk factors for suicide attempt among enlisted RC soldiers in-theater include being female, less educated, early in service and currently married. These factors are largely consistent with both the total enlisted RC population and deployed enlisted AC soldiers. The RC suicide attempt rate was substantially lower than the AC rate. The pattern of risk for RC enlisted soldiers by time into deployment was similar to that for AC enlisted soldiers, reinforcing mid-deployment as an important period for further study and enhanced suicide risk assessment and prevention. Given the challenges of monitoring and intervening with deactivated RC soldiers, it is important to maximize prevention efforts during the narrow windows of RC activation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Army STARRS Team consists of Co-Principal Investigators: Robert J. Ursano, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences) and Murray B. Stein, MD, MPH (University of California San Diego and VA San Diego Healthcare System)

Site Principal Investigators: Steven Heeringa, PhD (University of Michigan), James Wagner, PhD (University of Michigan) and Ronald C. Kessler, PhD (Harvard Medical School)

Army scientific consultant /liaison: Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH (Office of the Deputy Under Secretary of the Army)

Other team members: Pablo A. Aliaga, MS (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); COL David M. Benedek, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Laura Campbell-Sills, PhD (University of California San Diego); Carol S. Fullerton, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Nancy Gebler, MA (University of Michigan); Robert K. Gifford, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Meredith House, BA (University of Michigan); Paul E. Hurwitz, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Sonia Jain, PhD (University of California San Diego); Tzu-Cheg Kao, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Lisa Lewandowski-Romps, PhD (University of Michigan); Holly Herberman Mash, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); James A. Naifeh, PhD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Tsz Hin Hinz Ng, MPH (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); Matthew K. Nock, PhD (Harvard University); Nancy A. Sampson, BA (Harvard Medical School); LTC Gary H. Wynn, MD (Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences); and Alan M. Zaslavsky, PhD (Harvard Medical School).

Funding

Army STARRS was sponsored by the Department of the Army and funded under cooperative agreement number U01MH087981 (2009–2015) with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health (NIH/NIMH). Subsequently, STARRS-LS was sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense (USUHS grant number HU0001–15-2–0004). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Health and Human Services, NIMH, or the Department of the Army, or the Department of Defense.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

In the past 3 years, Dr. Kessler received support for his epidemiological studies from Sanofi Aventis; was a consultant for Johnson & Johnson Wellness and Prevention, Sage Pharmaceuticals, Shire, Takeda; and served on an advisory board for the Johnson & Johnson Services Inc. Lake Nona Life Project. Kessler is a co-owner of DataStat, Inc., a market research firm that carries out healthcare research. Dr. Stein has in the past three years been a consultant for Actelion, Alkermes, Aptinyx, Bionomics, Dart Neuroscience, Healthcare Management Technologies, Janssen, Neurocrine Biosciences, Oxeia Biopharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Resilience Therapeutics. Dr. Stein has stock options in Oxeia Biopharmaceticals. The remaining authors report nothing to disclose.

Role of the funder/sponsor

As a cooperative agreement, scientists employed by NIMH (Lisa J. Colpe, PhD, MPH and Michael Schoenbaum, PhD) and Army liaisons/consultants (COL Steven Cersovsky, MD, MPH USAPHC and Kenneth Cox, MD, MPH USAPHC) collaborated to develop the study protocol and data collection instruments, supervise data collection, interpret results, and prepare reports. Although a draft of this manuscript was submitted to the army and NIMH for review and comment prior to submission, this was with the understanding that comments would be no more than advisory.

References

- Black SA, Gallaway S, Bell MR, & Ritchie EC (2011). Prevalence and Risk Factors Associated with Suicides or Army Soldiers 2001–2009. Military Psychology, 23, 433–451. [Google Scholar]

- Bonds TM, Baiocchi D, & L.L. McDonald. (2010). Army Deployments to OIF and OEF: RAND ARROYO CENTER. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks RD, Corrigan E, Toussaint M, & Pecko JA (2018). Surveillance of Suicidal Behavior January through December 2017 PHR No. S.0049809.1. [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese JR, Prescott M, Tamburrino M, Liberzon I, Slembarski R, Goldmann E, . . . Galea S (2011). PTSD comorbidity and suicidal ideation associated with PTSD within the Ohio Army National Guard. J Clin Psychiatry, 72(8), 1072–1078. doi: 10.4088/JCP.11m06956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen GH, Fink DS, Sampson L, Tamburrino M, Liberzon I, Calabrese JR, & Galea S (2017). Coincident alcohol dependence and depression increases risk of suicidal ideation among Army National Guard soldiers. Ann Epidemiol, 27(3), 157–163.e151. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DoA. (2012). Department of the Army: Army 2020: Generating health & discipline in the force ahead of the strategic reset Washington, DC: Department of the Army [Google Scholar]

- DoD. (2018). Military and Civilian Personnel by Service/Agency by State/Country Reports In D. M. D. Center (Ed.), Department of Defense Personnel, Workfoce Reports & Publications Department of Defense. [Google Scholar]

- DoDSER. (2017). Department of Defense Suicide Event Report Calendar Year 2016 Annual Report. [Google Scholar]

- Fox KR, Millner AJ, Mukerji CE, & Nock MK (2018). Examining the role of sex in self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris EC, & Barraclough B (1997). Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry, 170, 205–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, & Milliken CS (2006). Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. Jama, 295(9), 1023–1032. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland RR, Kress AM, & Frost LZ (2012). Association between mental health conditions diagnosed during initial eligibility for military health care benefits and subsequent deployment, attrition, and death by suicide among active duty service members. Mil Med, 177(10), 1149–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE (2005). Why people die by suicide Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Gebler N, Naifeh JA, Nock MK, . . . Heeringa SG (2013). Design of the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, 22(4), 267–275. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline A, Ciccone DS, Falca-Dodson M, Black CM, & Losonczy M (2011). Suicidal ideation among National Guard troops deployed to Iraq: the association with postdeployment readjustment problems. J Nerv Ment Dis, 199(12), 914–920. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3182392917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline A, Falca-Dodson M, Sussner B, Ciccone DS, Chandler H, Callahan L, & Losonczy M (2010). Effects of repeated deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan on the health of New Jersey Army National Guard troops: implications for military readiness. Am J Public Health, 100(2), 276–283. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2009.162925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson GE, Highfill-McRoy RM, & Booth-Kewley S (2008). Psychiatric diagnoses in historic and contemporary military cohorts: combat deployment and the healthy warrior effect. Am J Epidemiol, 167(11), 1269–1276. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Olson MA, & Joiner TE (2019). Implicit interpersonal evaluations as a risk factor for suicidality: Automatic spousal attitudes predict changes in the probability of suicidal thoughts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MHAT-V. (2008). Mental Health Advisory Team V - Operation Iraqi Freedom 06–08: Iraq; Operation Enduring Freedom 8: Afghanistan. [Google Scholar]

- Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, & Hoge CW (2007). Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. Jama, 298(18), 2141–2148. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millner AJ, Ursano RJ, Hwang I, A , J. King, Naifeh JA, Sampson NA, . . . Nock MK (2017). Prior Mental Disorders and Lifetime Suicidal Behaviors Among US Army Soldiers in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Suicide Life Threat Behav. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naifeh JA, Mash HBH, Stein MB, Fullerton CS, Kessler RC, & Ursano RJ (2019). The Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS): progress toward understanding suicide among soldiers. Mol Psychiatry, 24(1), 34–48. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0197-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naifeh JA, Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Gonzalez OI, Fullerton CS, Herberman Mash HB, . . . Stein MB (2019). Suicide attempts among activated soldiers in the U.S. Army reserve components. BMC Psychiatry, 19(1), 31. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1978-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Stein MB, Heeringa SG, Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, . . . Kessler RC (2014). Prevalence and correlates of suicidal behavior among soldiers: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 514–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Ursano RJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Jain S, Raman R, . . . Kessler RC (2015). Mental Disorders, Comorbidity, and Pre-enlistment Suicidal Behavior Among New Soldiers in the U.S. Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Suicide Life Threat Behav, 45(5), 588–599. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger MA, Smolenski DJ, Skopp NA, Metzger-Abamukang MJ, Kang HK, Bullman TA, . . . Gahm GA (2015). Risk of suicide among US military service members following Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom deployment and separation from the US military. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(6), 561–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roalfe AK, Holder RL, & Wilson S (2008). Standardisation of rates using logistic regression: a comparison with the direct method. BMC Health Serv Res, 8, 275. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesselman JJ (1982). Case-control studies: Design, conduct, analysis New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum M, Kessler RC, Gilman SE, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, . . . Cox KL (2014). Predictors of suicide and accident death in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS): results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry, 71(5), 493–503. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street AE, Gilman SE, Rosellini AJ, Stein MB, Bromet EJ, Cox KL, . . . Kessler RC (2015). Understanding the elevated suicide risk of female soldiers during deployments. Psychological Medicine, 45(4), 717–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street AE, Vogt D, & Dutra L (2009). A new generation of women veterans: Stressors faced by women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, & Stein MB (2014). The Army study to assess risk and resilience in servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry, 77(2), 107–119. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2014.77.2.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Cox KL, Naifeh JA, Fullerton CS, . . . Stein MB (2015). Nonfatal Suicidal Behaviors in U.S. Army Administrative Records, 2004–2009: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry, 78(1), 1–21. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2015.1006512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, Herberman Mash HB, Nock MK, Aliaga PA, . . . Stein MB (2018a). Risk Factors Associated With Attempted Suicide Among US Army Soldiers Without a History of Mental Health Diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(10), 1022–1032. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Naifeh JA, Herberman Mash HB, Nock MK, Aliaga PA, . . . Stein MB (2018b). Risk factors associated with attempted suicide among U.S. Army soldiers without a history of mental health diagnosis. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(10), 1022–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Kessler RC, Stein MB, Naifeh JA, Aliaga PA, Fullerton CS, . . . Heeringa SG (2016). Risk Factors, Methods, and Timing of Suicide Attempts Among US Army Soldiers. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(7), 741–749. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ursano RJ, Naifeh JA, Kessler RC, Gonzalez OI, Fullerton CS, Mash HH, . . . Stein MB (2018). Nonfatal Suicidal Behaviors in the Administrative Records of Activated U.S. Army National Guard and Army Reserve Soldiers, 2004–2009. Psychiatry, 81(2), 173–192. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2018.1460716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup JT, Townsend L, Crystal S, & Olfson M (2012). A systematic review of validated methods for identifying suicide or suicidal ideation using administrative or claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf, 21 Suppl 1, 174–182. doi: 10.1002/pds.2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger JW, O’Connell C, & Cottrell L (2018). Examination of Recent Deployment Experience Across the Services and Components: RAND CORPORATION. [Google Scholar]

- Willett JB, & Singer JD (1993). Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol, 61(6), 952–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.