Abstract

Purpose

Physician burnout affects approximately half of U.S. physicians, significantly higher than the general working population. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence of burnout specifically among hand surgeons and to identify factors unique to the practice of hand surgery that may contribute to burnout.

Methods

A web-based survey, developed in conjunction with the American Medical Association, was administered to all active and lifetime members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand using the Mini Z Burnout assessment tool. Additional data was collected regarding physician demographics and practice characteristics.

Results

The final cohort included 595 U.S. hand surgeons (ASSH members) and demonstrated that 77% of respondents were satisfied with their job though 49% regarded themselves as having burnout. Lower burnout rates were correlated with physicians older than 65, those who practice in an outpatient setting, practice hand surgery only, visit 1 facility per week, have a lower commute time, those who perform 10 or fewer surgeries per month, and are considered “grandfathered” for Maintenance of Certification. It was shown that sex, the use of physician extenders, compensation level, and travel club involvement had no impact on burnout rates.

Conclusions

The survey demonstrates that nearly half of U.S. hand surgeons are experiencing burnout, despite the fact that most are satisfied with their jobs. There is a need to increase awareness and promote targeted interventions to reduce burnout, such as creating a strong team culture, improving resiliency, and leadership enhancement.

INTRODUCTION

Physician burnout is difficult to define though the concept has garnered increased attention as its prevalence is learned. The Maslach Burnout Inventory, one of the most frequently used instruments to study burnout, defines burnout as a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and decreased personal accomplishment.1 It is noted to be the result of chronic stress associated with working in the human services, i.e. any occupation that works directly with other people, such as health care, customer service, criminal justice, education, clergy, etc.1 In 2012, Shanafelt et al. reported that approximately 46% of U.S. physicians had at least one symptom of burnout, which was significantly higher than the 28% level seen in the general U.S. working population.2 In 2014, that number had grown to 54%.3 While physicians may have higher financial compensation, or an occupation of prestige, this does not seem to be protective from burnout.

Burnout has detrimental effects on both the individual and at a system-wide level; it has been associated with physical ailments such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysregulation, and male infertility.4,5 It also has negative psychologic sequelae, contributing to depression, relationship problems, alcohol and substance abuse, and suicide.4,5 Given these effects, it is not surprising that burnout has a negative effect on job performance through erosion of professionalism and quality of care, increased medical errors, greater employee absenteeism and turnover, decreased professional work effort (work hours) and productivity, and early retirement.4–6 Burnout adversely affects prescribing patterns and test ordering, and increases malpractice suits.7 This results in added institutional cost to the healthcare industry.8,9 Clearly, burnout is negatively affecting the practice of medicine.

With the higher prevalence among physicians, it seems that burnout is more likely a result of the medical environment and care delivery system in which physicians practice, rather than the personal characteristics of the physicians themselves.2,10 Some of the factors that have been linked to burnout include: excessive workload, loss of autonomy, increasing clerical burdens (electronic health record (EHR), in particular), and maintenance of certification requirements.11–13 While burnout affects physicians of all subspecialties, the rate varies among different specialties. Hand surgery is unique as a specialty in that it involves surgeons from varied backgrounds such as general surgery, plastic surgery, and orthopaedics, and a hand surgeon’s practice may vary considerably from another’s. It is not known if there are unique factors pertaining to the practice of hand surgery that contribute to burnout, or are protective, though exploring them may help to inform interventions to reduce burnout for hand surgeons.

Building awareness is also necessary in managing this epidemic. The American Orthopaedic Association (AOA) identified burnout as a “Critical Issue” and called on societies to provide support for their members in developing interventions that may revert the trend of increasing physician burnout.4 Although rates of burnout have been reported among orthopaedic and plastic surgeons, the prevalence of burnout among hand surgeons specifically is unknown. While there may be no obvious reason to suspect that burnout would be any different for the general, orthopaedic and plastic surgeons that have subspecialized in hand surgery, it is also not known if the unique features of such a practice contribute to burnout in a meaningful way. The identification of any of these factors could facilitate the American Society for Surgery of the Hand (ASSH), and the American Association of Hand Surgery (AAHS), in their efforts to answer the call of the AOA.

As an initial step in managing burnout in hand surgeons, the ASSH partnered with the American Medical Association (AMA) to assess the prevalence of burnout among hand surgeons and to determine if there are unique factors pertaining to the practice of hand surgery that contribute to burnout. The goal was to promote awareness among the ASSH membership and to use the results to inform future quality improvement efforts targeted at reducing burnout for hand surgeons.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The survey qualified for IRB exemption as part of a quality improvement initiative. A web-based survey was designed and administered in conjunction with the AMA using the 10-item Mini Z (version 2.0) survey to assess the rate of burnout, job satisfaction, stress, and contributors to burnout among members (Appendix 1).14,15 All active and lifetime members of the ASSH were invited via email to participate in the anonymous online assessment. The invitation remained open from June 21st - July 23rd, 2018. The Mini Z v2.0 survey was chosen as it allowed comparison of ASSH member responses to those of a previously obtained AMA benchmark sample of 1000 U.S. physicians from a wide range of specialties, and it minimizes survey burden compared to the longer (22 item) Maslach Burnout Inventory. The final cohort was limited to respondents in the U.S.

The mini-Z v2.0 survey measures burnout using a single question item that asks respondents to use their own definition of “burnout” and rate their level of symptoms on a 5-point Likert scale. This single burnout question has been previously validated for physicians with very good correlation to the Maslach Burnout Inventory.16,17 The other items of the Mini Z v2.0 survey assess respondent perception of work environment support (subscale 1) and work pace and EHR support (subscale 2). Each subscale consists of 5 items and has a maximum score of 25 points, with higher scores indicating a more positive work environment. The total score provides a measure of a joyful workplace, with a maximum score of 50. Targets of 80% or higher for each subscale have been set by the AMA to indicate a highly supportive practice or an office with reasonable pace and manageable EHR stress (unpublished).

In addition to the standard 10-items of the Mini Z v2.0 survey, respondents were also asked questions related to demographic characteristics, practice characteristics, call arrangement, and other factors specifically related to hand surgery that may contribute to higher or lower levels of burnout. Demographic characteristics included: age, sex, marital status, and number of dependent children. Practice characteristics included: years in practice, practice setting, practice ownership model, region, specialty, number of facilities traveled to per week, compensation model, perception of fair compensation, use of EHR and vendor, method of documentation, and time allocation on types of work, including EHR. Call arrangement details assessed included: compensation for call, types of cases, and replant coverage. Additional factors that were examined included: maintenance of certification status, travel club participation, involvement in a legal suit, and intent to cut hours or retire in the near future. Participants were asked a final open-ended question at the conclusion of the survey: “Tell us more about your stresses and what [the ASSH] can do to minimize them.”

The main outcomes of interest included respondent’s satisfaction with their job, respondent’s perceived level of burnout, and total Mini Z score. The satisfaction and burnout outcomes were assessed respectively by a single question in the Mini Z v2.0 instrument. To calculate the frequency of burnout, responses to the single burnout question were collapsed into three categories: burnout (lowest three answer options), stressed (2nd highest answer option), and no burnout (highest answer option). Responses to the job satisfaction question were similarly collapsed into three categories: not satisfied, neutral, and satisfied. All outcomes were compared to the benchmark AMA physician cohort.

The total Mini Z v2.0 scores were compared in unadjusted bivariate analyses based on demographic characteristics, practice characteristics, and the additional factors that were assessed in the survey using paired t-tests among subgroups (α = 0.05). A multivariable linear regression was performed to identify the characteristics assessed in the survey that had the greatest impact on physician burnout and satisfaction among ASSH member respondents. For the burnout regression, the dependent variable was (Q2.2): “Using your own definition of “burnout,” please choose one of the numbers below.” The order in which the predicter variables were entered into the model was as follows: (Q12.2) Years since residency, (Q2.10) EMR Frustration / proficiency, (Q5.8) Number of physicians (FTEs), (Q2.3) Professional values, (Q2.8) Work Atmosphere, (Q2.6) Time Spend with EMR, (Q2.5) Stress at work, (Q2.4) Team work, (Q2.9) Control over workload, (Q2.1) Satisfaction, (Q2.7) Time with Documentation, and (Q12.1) Age. For the satisfaction regression, the dependent variable was (Q2.1): “Overall, I am satisfied with my current job.” The order in which the variables were entered was: (Q12.2) Years since residency, (Q2.10) EMR Frustration / proficiency, (Q5.8) Number of physicians (FTEs), (Q2.3) Professional values, (Q2.8) Work Atmosphere, (Q2.6) Time Spend with EMR, (Q2.5) Stress at work, (Q2.4) Team work, (Q2.9) Control over workload, (Q2.2) Using your own definition of “burnout,” please choose one of the numbers below, (Q2.7) Time with Documentation, and (Q12.1) Age (Appendix 1)

The open-ended responses to the inquiry about stressors and what the ASSH can do to minimize them were examined for the most commonly mentioned themes.

RESULTS

A total of 628 active ASSH members completed the survey. Of those respondents, 595 were within the United States and their responses were used for this study. The overall response rate was 34.9%.

Satisfaction with Current Job

Over three-fourths (77%) of survey respondents reported satisfaction with their jobs, on par with the 80% satisfaction level seen among benchmark physicians. Approximately one in nine (11%) said they were not satisfied.

Burnout Level

Almost half (49%) of survey respondents regarded themselves as having burnout, substantially higher than the 29% benchmark level. An additional one-third said that they were under stress, while 17% reported having no symptoms of burnout.

Mini-Z v2.0 Scores Summary

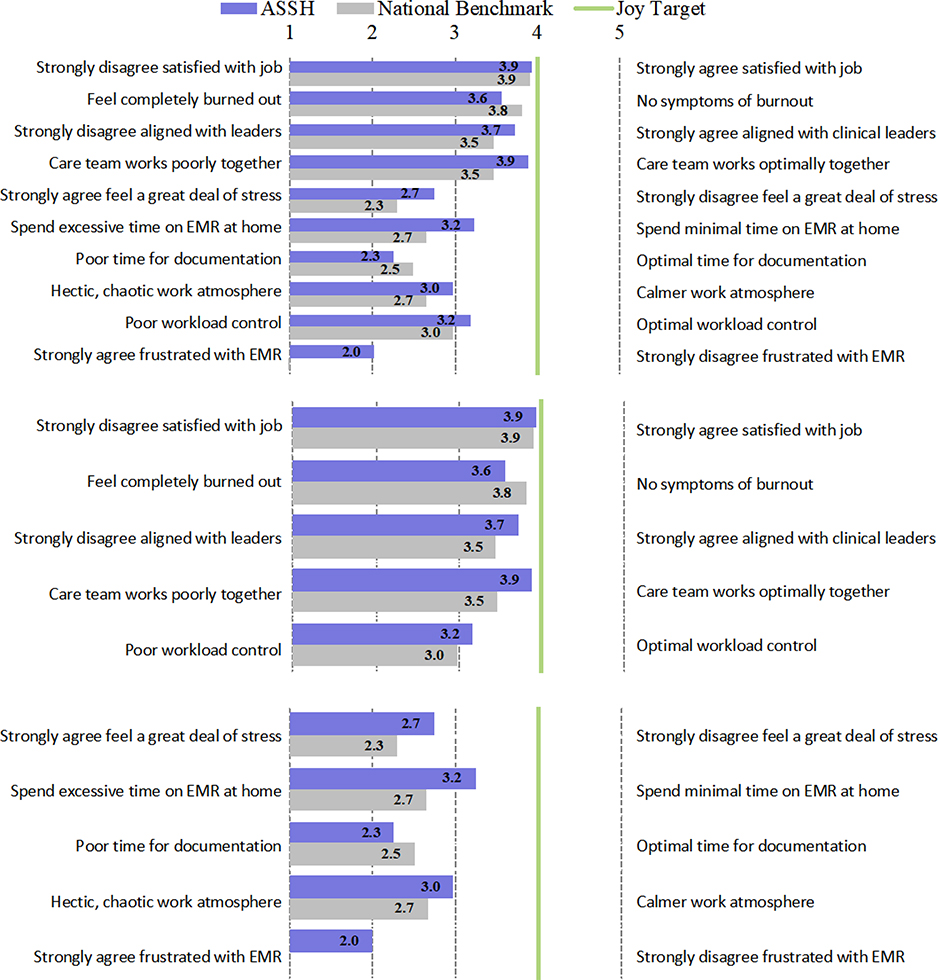

The overall Mini-Z score (composite score for a joyful workplace) for survey respondents was 63.1%, similar to the national benchmark of 61.6%. Both are below the desired joy target of ≥80%, however. Survey respondents graded 73.0% for Highly Supportive Practice and 53.0% for Reasonable Pace and Manageable Stress, compared to 70.4% and 50.6% respectively in the national benchmark. Cumulative results for the Mini-Z score and each subscale are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Detailed factors for overall Mini-Z and subscales. The first 10 measures are ‘Total Mini-Z’, the next 5 measures are “Subscale 1 – Highly Supportive Practice,” and the final 5 measures are “Subscale 2 – Reasonable Pace and Manageable Stress.” The figure was created by the American Medical Association and used with permission.

With regard to specific physician demographics, clinicians aged 65 years or older reported less burnout than others (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences in burnout rates based on sex (p > 0.05). (Appendix 2).

Lower rates of burnout were found in those who primarily practice in an outpatient setting, practice hand surgery only, visit 1 facility a week, have a lower commute time, and those with 10 or fewer surgical cases per month (p < 0.05) (Appendix 3).

Survey respondents who take any type of call, including replant call, experienced higher burnout rates than those who do not take call (p < 0.05). Burnout levels were similar regardless of whether the clinician receives additional compensation for call (p > 0.05) (Appendix 4).

Burnout rates were lower among survey respondents whose recertification was “grandfathered-in” rather than having to take the re-certification examination (p < 0.05). Not being named in a legal suit trended towards a lower burnout rate, though did not meet statistical significance (p < 0.1). Utilizing an allied health professional or participation in a hand surgery travel club likewise had no significant impact on burnout rates (p > 0.05) (Appendix 5).

While burnout rates were similar across compensation models, clinicians who perceived their compensation as ‘fair’ were less likely to report burnout (p < 0.05).

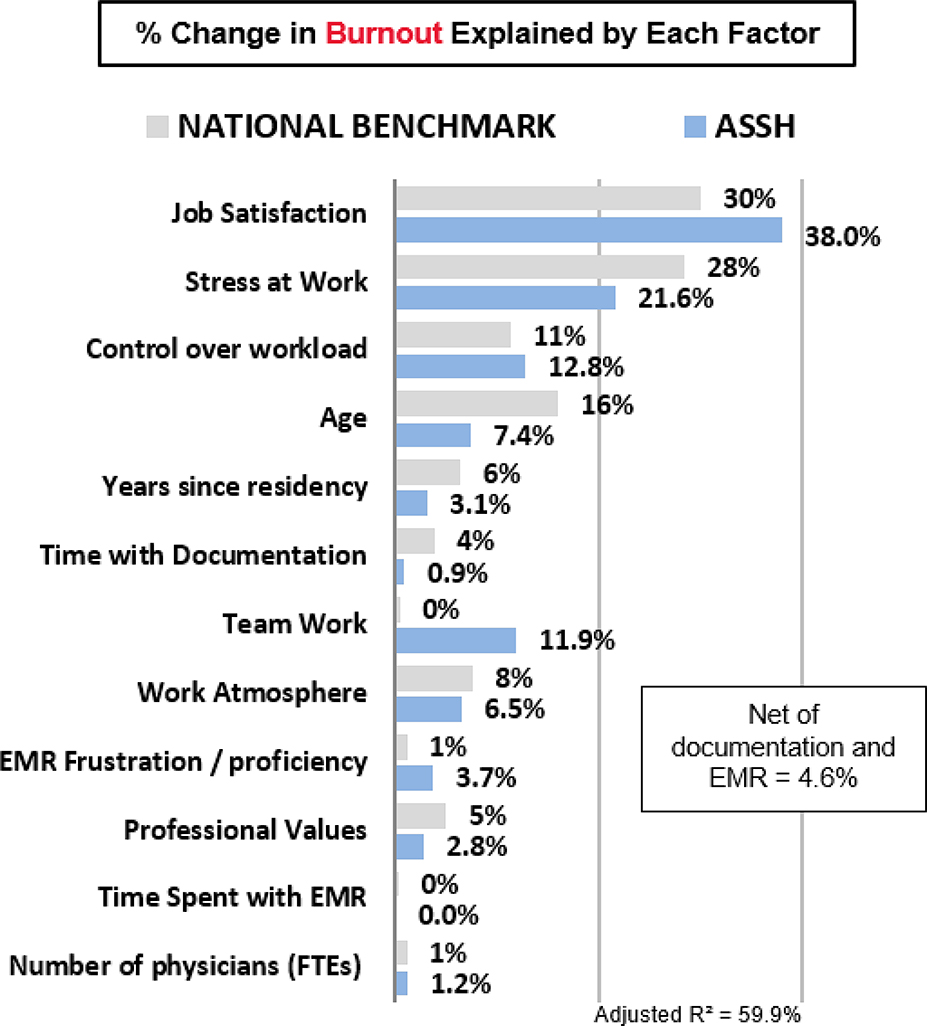

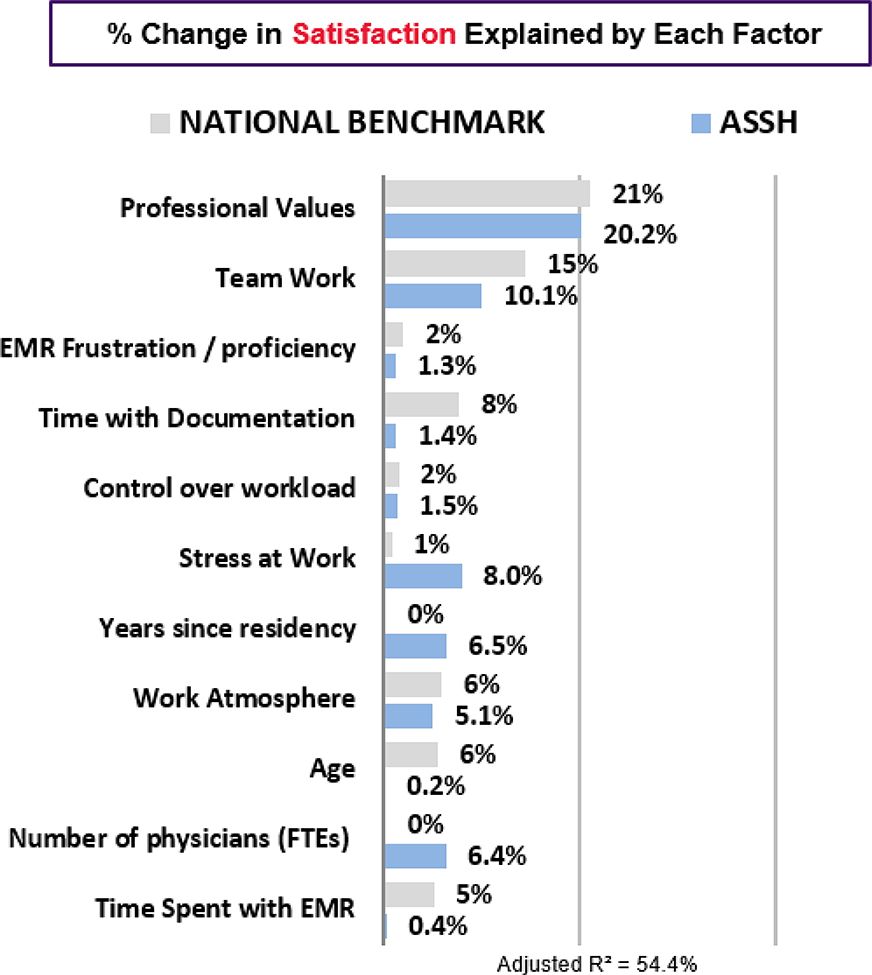

The regression analysis indicates that beyond overall stress and job satisfaction, hand surgeon burnout was mostly determined by: lack of control over workload, inefficient team work, age, and work atmosphere, more so than EHR or documentation factors specifically (Figure 2). The top determinants of physician satisfaction for survey respondents was alignment of professional values with those of clinical leaders, efficient team work, low stress at work, and years since residency (Figure 3).

Figure 2:

Determinants of Physician Burnout. Percent change in burnout explained by each factor for both ASSH clinicians and the National Benchmark. The figure was created by the American Medical Association and used with permission.

Figure 3:

Determinants of Physician Satisfaction. Percent change in satisfaction explained by each factor for both ASSH clinicians and the National Benchmark. The figure was created by the American Medical Association and used with permission.

Primary Stressors

Despite the regression analysis findings, numerous survey respondents highlighted EHR frustrations and declining reimbursements as primary contributors to burnout (Table 1). They also reported that hostile external environments, particularly from insurance companies and governmental organizations, added to their stress.

Table 1:

Specific Stressors mentioned by ASSH members.

| Number of Mentions | |

|---|---|

| EHR / EMR / IT Issues (Net) | |

| Difficulties with EMR / EHRs | 63 |

| Needing to take care of EHR/EMR documentation before / after shift | 14 |

| Would like access to different documentation methods | 7 |

| Need to use EHR / EMR to satisfy billing goals | 6 |

| Would like to improve EMR utilization | 5 |

| Billing / costs management (Net) | |

| Poor / decreasing reimbursement | 48 |

| Scheduling / Time Issues (Net) | |

| EHR/EMR documentation takes too long | 41 |

| Insurance / Regulatory / Policy Stresses (Net) | |

| Insurance policy / requirements / restrictions | 30 |

| Government policy / requirements / restrictions | 19 |

| Malpractice claims | 7 |

| Tort reform | 4 |

| Workload Issues (Net) | |

| Eliminate overnight call / On call | 22 |

| Unrealistic / improper goals set for number of patients seen / too many patients | 12 |

| Support / Management Issues (Net) | |

| Lack of independence / ability to make own decisions | 19 |

| Not enough administrative support / would like more support staff | 10 |

| Management / administration prioritizes profits over patients | 7 |

| Quality of Patient Care (Net) | |

| Poor quality of care / Not providing quality of care | 17 |

| Communication Issues (Net) | |

| Difficulties with patient / family communication | 9 |

| Eliminate / disregard patient satisfaction surveys | 7 |

| Quality of Work Environment Issues (Net) | |

| Poor compensation | 8 |

| Not enough opportunities for / recognition of / support for research | 6 |

| Poor work / life balance | 5 |

| Additional Stresses (Net) | |

| Leave medicine | 21 |

| Increase ASSH advocacy / ASSH should do more | 21 |

| Board certification process | 12 |

| Increase AMA advocacy / AMA should do more | 5 |

| Nothing can be done / part of the job | 8 |

| None / no stresses | 10 |

| Don't know | 4 |

DISCUSSION

The current survey assessed burnout and numerous related factors to hand surgeons and found they are subject to burnout at a rate considerably higher than the physicians in the 2016 AMA benchmark cohort. The AMA cohort included physicians from multiple specialties, withthe rate of burnout varying by specialty. The AMA cohort was utilized so that we could directly compare our results with others obtained from the Mini Z v2.0 instrument. This instrument was used as it can assess burnout at the system level, has an established process distributed nationally through hospitals and organizations which thereby permit comparisons across specialties. Unfortunately, we cannot parse-out the individual surgical subspecialties from that data set. While using a different instrument, a 2017 Medscape survey found that 53% of plastic surgeons, 49% of orthopaedic surgeons, and 49% of general surgeons acknowledged burnout.18 As hand surgeons emanate from these clinical backgrounds, it is not surprising that the burnout rate within our subspecialty, as identified in our study, falls within this spectrum. While we would like to compare our results directly to those of the general surgeons, plastic surgeons, and orthopaedic surgeons, those data were not readily available.

Some have suggested that burnout may be mitigated by high levels of job satisfaction, but this may not always be the case.4,19 Hand surgeons are generally satisfied with their jobs, with 77% of those surveyed reporting as such, despite that nearly half of survey respondents reported being burned-out. This apparent discrepancy highlights the fact that burnout is multifactorial (Figures 1–3, Table 1). In our multivariable analysis, job satisfaction was the most influential factor affecting the percentage of burnout, though still only represented 38%. As such, satisfaction and burnout are not mutually exclusive. It may also be that burnout measurement could be flawed or biased. While it has been validated against the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Mini Z v2.0 instrument simply asks if the individual is burned-out, based on one’s own definition. Additionally, this discrepancy may indicate that hand surgeons have grit and resilience, characteristics that have recently been found to be protective against burnout.20

Many of the factors associated with burnout in hand surgeons include the lack of control over workload, inefficient team work, age, and work atmosphere (Figure 2). The top determinants of physician satisfaction was alignment of professional values with those of clinical leadership, efficient team work, low stress at work, and years since residency. When asked specifically to comment on their stressors, more survey respondents documented their concerns over the EHR more than any other factor (Table 1). A recent, large national study reported that physicians who use an EHR and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) had higher rates of burnout and were less likely to be satisfied given their clerical burden.13 Orthopaedic surgeons as a subspecialty had worse satisfaction with EHR and clerical burden when compared to other specialties.13 This also appears to be the case with hand surgeons. While this may be a reporting bias, it may also indicate that hand surgeons feel that this is the factor most able to be changed. As the EHR is not specific to any one specialty, additional work is needed to develop specific EHR platforms that are hand surgery specific so that the clerical burden can be reduced.

Some limitations of the current study are the survey response rate and the fact that only full active members were surveyed, not including candidate members. While a 34.9% response rate is on par with other surveys done by the ASSH, a more inclusive sample size would likely give a more accurate representation of the feelings of the ASSH membership. Previous studies have demonstrated a significantly higher burnout rate in younger surgeons compared to those with more experience.21,22 Among hand surgeons, age was also found to be a relevant factor. It is therefore possible that the current survey actually underestimates the prevalence of burnout in hand surgeons by only surveying active members and excluding younger, candidate members.

Because of the impact that burnout has on the practice of medicine, Dr. Tait Shanafelt, one of the leaders in burnout research, has advocated for an expeditious, multifaceted approach to combat physician burnout. He has previously commented that, “If [there was] a system issue that affected quality of care, limited access to care, eroded patient satisfaction, [and] affected up to half of patient encounters [like burnout does], [one] would immediately assign a team of systems engineers, physicians, and administrators to fix that problem rapidly.”23 That system issue does exist and is physician burnout. Action is necessary.

There are many strategies that can limit burnout, both on an organizational level as well as the individual level. Dr. Andrew Palmer, in his Presidential address in 1998, emphasized finding balance in one’s life.24 In 2009, Dr. Terry Light spoke at the ASSH Resident and Fellows Conference about finding joy in hand surgery practice.25 Dr. James Chang, in his Presidential address in 2018, noted the increased prevalence of physician burnout and echoed the importance of finding that joy. 26 Some of the individual strategies that have been shown to limit burnout include: maintaining a positive outlook, spending 20% of one’s work effort on the professional activities considered most meaningful, involvement with colleagues, taking vacations, exercising, avoiding delayed gratification, and mindfulness training.7,27 Being aware of burnout and regularly self-assessing one’s happiness is critical if one is to make real-time adjustments to prevent burnout from setting-in. The Physician Well-Being Index is one such tool for repeated self-assessment.28 Burnout-combatting strategies that place sole responsibility on the individual, however, are likely to be unsuccessful on a system level.

Shanafelt and Noseworthy provided organizational strategies that have been shown to promote engagement and reduce burnout. These include: acknowledging and assessing the problem of burnout, harnessing the power of leadership, developing and implementing targeted interventions, cultivating community at work, using rewards and incentives wisely, aligning values and strengthening culture, promoting flexibility and work-life integration, providing resources to promote resilience and self-care, and facilitating and funding organizational science.9 The AMA STEPS Forward program provides essential tools and resources to promote best practice behaviors by creating a strong team culture, improving resiliency, decreasing stress and physician suicide all at the same time of promoting joy within one’s organization.15 Similar physician well-being programs are offered by other societies including the American College of Surgeons. Ultimately, burnout prevention must be a priority in order to realize change.

This study demonstrates that nearly half of U.S. hand surgeons are experiencing burnout despite the fact that most are satisfied with their jobs. While there have been efforts made to reduce burnout, clearly more needs to be done. Our intent was to document the prevalence of burnout among practicing hand surgeons and identify factors pertaining to the practice of hand surgery that contribute to burnout. We hope that with this data, the ASSH, and other societies, will continue to promote future quality improvement efforts and targeted interventions to reduce burnout.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Relevance.

Burnout has been shown to negatively affect physicians, their families, patient care, and the healthcare system as a whole. The findings should promote awareness among hand surgeons and inform future quality improvement efforts targeted at reducing burnout for hand surgeons.

Acknowledgement

“The authors would like to thank Pamela Schroeder from the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, Lindsey E. Goeders, MBA, from the American Medical Association, and Brad Wozney, MD and Christopher Elfner from Bellin Health, for their contributions to the content and review of this manuscript.”

Funding: No source of external funding was used for this study.

Contributor Information

Nathan T. Morrell, Department of Orthopaedics & Rehabilitation, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM.

Erika D. Sears, Section of Plastic Surgery, Michigan Medicine, VA Ann Arbor Center for Clinical Management Research, Ann Arbor MI.

Mihir J. Desai, Vanderbilt Univ. Medical Center, Franklin TN.

Michael J. Forseth, Summit Orthopedics/University of Minnesota Dept. of Orthopedic Surgery, 2620 Eagan Woods Drive, Eagan MN 55121.

Walter B. McClelland, Jr, Orthopaedic Surgery, 2001 Peachtree Rd, NE Su. 705, Atlanta, GA 30309.

James Chang, Div. of Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Stanford University Medical Center, 770 Welch Rd., Suite 400, Palo Alto, CA 94304.

Sanjeev Kakar, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Mayo Clinic, 200 First St SW, Rochester MN 55905,.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory 3rd ed Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ames SE, Cowan JB, Kenter K, Emery S, Halsey D. Burnout in Orthopaedic Surgeons: A Challenge for Leaders, Learners, and Colleagues: AOA Critical Issues. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(14):e78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels AH, DePasse JM, Kamal RN. Orthopaedic Surgeon Burnout: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2016;24(4):213–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, et al. Physician Burnout, Well-being, and Work Unit Safety Grades in Relationship to Reported Medical Errors. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shanafelt TD, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Avoiding burnout: the personal health habits and wellness practices of US surgeons. Ann Surg. 2012;255(4):625–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal Study Evaluating the Association Between Physician Burnout and Changes in Professional Work Effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(4):422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive Leadership and Physician Well-being: Nine Organizational Strategies to Promote Engagement and Reduce Burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery A The inevitablity of physician burnout: Implications for interventions. Burnout Research. 2014;1(1):50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: Primary Care Physician Workload Assessment Using EHR Event Log Data and Time-Motion Observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sinsky C, Tutty M, Colligan L. Allocation of Physician Time in Ambulatory Practice. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):683–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. Addressing Physician Burnout: The Way Forward. JAMA. 2017;317(9):901–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linzer M, Poplau S, Babbott S, et al. Worklife and Wellness in Academic General Internal Medicine: Results from a National Survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):1004–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.AMA Steps Forward: Preventing Physician Burnout. https://www.stepsforward.org/modules/physician-burnout Accessed December 6, 2017.

- 16.Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress and Health. 2004;20:75–79. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medscape 2017 Physician Lifestyle Report. https://www.medscape.com/sites/public/lifestyle/2017 Accessed September 3, 2018.

- 19.Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, Cull A, Gregory WM. Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet. 1996;347(9003):724–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Underdahl L, Jones-Meineke T, Duthely LM. Reframing physician engagement: An analysis of physician resilience, grit, and retention. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2018;11(3):243–250. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell DA, Jr., Sonnad SS, Eckhauser FE, Campbell KK, Greenfield LJ. Burnout among American surgeons. Surgery. 2001;130(4):696–702; discussion 702–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sargent MC, Sotile W, Sotile MO, Rubash H, Barrack RL. Quality of life during orthopaedic training and academic practice. Part 1: orthopaedic surgery residents and faculty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(10):2395–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parks T What makes doctors great also drives burnout: A double-edged sword. AMA Wire Jun 21, 2016;Life & Career. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer AK. Presidential address: balance. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(1):1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Light TR. Finding joy in your hand surgery practice. J Hand Surg Am. 2010;35(2):181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang J ASSH Presidential Address: joy of hand surgery J Hand Surg Am, 43 (12) (2018), pp. 1061–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dyrbye LN, Satele D, Shanafelt T. Ability of a 9-Item Well-Being Index to Identify Distress and Stratify Quality of Life in US Workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(8):810–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.