Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 has infected millions worldwide. The virus is novel, and currently there is no approved treatment. Convalescent plasma may offer a treatment option. We evaluated trends of IgM/IgG antibodies/plasma viral load in donors and recipients of convalescent plasma. 114/139 (82 %) donors had positive IgG antibodies. 46/114 donors tested positive a second time by NP swab. Among those retested, the median IgG declined (p < 0.01) between tests. 25/139 donors with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 were negative for IgG antibodies. This suggests that having had the infection does not necessarily convey immunity, or there is a short duration of immunity associated with a decline in antibodies. Plasma viral load obtained on 35/39 plasma recipients showed 22 (62.9 %) had non-detectable levels on average 14.5 days from positive test versus 6.2 days in those with detectable levels (p < 0.01). There was a relationship between IgG and viral load. IgG was higher in those with non-detectable viral loads. There was no relationship between viral load and blood type (p = 0.87) or death (0.80). Recipients with detectable viral load had lower IgG levels; there was no relationship between viral load, blood type or death.

Keywords: Adults, Humans, SARS virus, COVID-19, Coronavirus, Viral load, COVID-19 serotherapy, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, Coronavirus infections, Plasma, Immunoglobulin M, Immunoglobulin G, Severe acute respiratory syndrome, Antigens, Viral, Blood transfusion

1. Introduction

The epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)/COVID-19) originated in Wuhan, China in Dec 2019 and rapidly spread worldwide. On March 11, 2020, The World Health Organization (WHO) declared this global spread a pandemic [1]. As of August 11, 2020, over 20 million people worldwide affected, with over 710,136 deaths [2].

The disease presentation ranges from asymptomatic to severe acute respiratory failure requiring intensive care support. Currently, intravenous Remdesivir is the only approved therapy for hospitalized patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. There are multiple therapies, and vaccine trials underway [3]. One such therapy is convalescent plasma. In March 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidance to study the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 convalescent plasma in treating seriously and critically ill patients [4].

Prior research involving the use of convalescent plasma for the treatment of viral infections such as SARS-CoV, Middle Eastern Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), H5N1 avian influenza, and H1N1 influenza have suggested that transfusion of convalescent plasma was effective, if given early in the course of the infection [[5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]]. Following infection, virus antigens stimulate the immune system to produce antibodies is detected in the blood. IgM antibodies detected after 3–5 days of symptom onset and IgG antibodies within 10–18 days. IgM titers then decline, while IgG antibody levels may increase four times or more as compared to the early phases of infection. Information on immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and duration is rather limited. Studies suggest thatt IgM expression is concurrent with IgG expression and both antibodies are associated with a high degree of variability in patients who test positive for the virus [11]. Li et al. [11] showed that in 49 potential donors, IgG antibodies increased after 4 weeks from the onset of SARS-CoC-2 symptoms, while in another study these antibodies decreased in 2–3 months after the infection [12].

Passive immunity delivered as anti-coronavirus antibodies from convalescent human plasma has promise of emerging as a therapeutic option in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 however, the selection of potential donors and the timing of the donations are critical to ensure therapeutic potency [11]. Shen et al. first described a case series of 5 critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 and Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) who showed improvement in clinical status after treatment with convalescent plasma containing neutralizing antibodies [13]. Subsequent studies have used using anywhere from 200 to 2400 ml of convalescent plasma with favorable outcomes [[14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]], with greatest benefit when plasma is administered within the first 14 days of infection [14].

In this prospective interventional study, we evaluated trends and determinants of SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers and viral loads in donors and critically ill patients who received the convalescent plasma.

2. Methods and study procedures

On April 9, 2020, Trinity Health Of New England (THOFNE) received FDA approval to conduct a Phase 2 clinical trial (NCT 04343261). The trial investigators received approval from the Trinity Health Of New England Institutional Review Board #SFH-20-23.

2.1. Plasma donors

Convalescent plasma collected from donors recovered from COVID-19 between the ages 18 and 90 with a confirmed positive nasopharyngeal swab SARS CoV-2 RNA test within the previous 45 days and symptom-free for at least 2 weeks.

One hundred thirty nine (139) potential donors were consented and tested again for SARS-CoV-2 RNA in nasopharyngeal swabs using real-time reverse transcription PCR (rRT-PCR). Subjects who retested positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA returned in 10 days for repeat test. Along with each nasopharyngeal swab, they had blood drawn for the measurement of SARS-CoV-2 specific antibody titers and plasma viral load. Subjects negative for SARS-CoV-2 with IgG titers >6.5 arbitrary units per mL (AU/mL) were referred to the Rhode Island Blood Center (Providence, Rhode Island, USA) where plasma was collected by apheresis methods. Plasma was frozen within 24 h of collection and labeled: “New Drug--Limited by Federal law to investigational use”, the IND number #19805 and ABO blood type.

2.2. Plasma recipients

Patients eligible to receive convalescent plasma between 18 and 90 years, confirmed severe or life threatening SARS-CoV-2 infection. Severe disease defined as at least one of the following: dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥30/min, blood oxygen saturation ≤ 93 %, partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen ratio <300 mm Hg, or lung infiltrates >50 % within 24–48 hours. Life-threatening disease defined as respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction [4].

Once subjects or legally authorized representatives gave informed consent, they received two consecutive convalescent plasma infusions of 200 mL each. Each unit transfused for 1 h, within 1–2 h apart. Viral load and antibody titers were measured immediately prior to receiving convalescent plasma and again on days 3, 5, and 7 following transfusion.

2.3. IgM and IgG antibody titers

IgM and IgG antibody titers measured in serum by Boston Heart Diagnostics (Framingham, MA) using commercially available chemiluminescent SARS-CoV-2 IgM and IgG assays from Diazyme (Poway, CA). The antibodies detected were against both SARS-CoV-2 full-length nucleocapsid protein, and partial-length glycoprotein spike protein. There was no cross reactivity with antibodies with non-SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus strains HKU1, NL63, OC43, or 229E, influenza A and B, parainfluenza, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, Epstein-Barr virus NA and VCA, measles virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella zoster, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Candida albicans.

Positive values for both antibody assays were serum values >1.0 AU/mL. Within and between run coefficients of variation based on 20 analyses at 4 concentration levels were 4.00 % and 2.51 % for IgM positive control samples (>1.0 AU/mL), and 2.50 % and 2.10 % for IgG positive control samples (>1.0 AU/mL), respectively. Linear reportable range of 1.0–10.0 AU/mL for IgM and of 0.20–100.00 AU/mL for IgG. Linearity studies showed r2 values of > 0.99 for both IgM and IgG. Prior studies indicated that the sensitivity of the IgG antibody test for identifying SARS-CoV-2 RNA positive subjects was 91.2 %, 95.6 % for both IgG and IgM antibody testing, while the specificity of the IgG assay for identifying negative subjects was 97.33 %.

2.4. Viral detection and viral load

Viral detection and quantification in plasma was performed using a research-use only rRT-PCR method which targets two regions of the SARS-CoV-2 N gene using TaqMan chemistry. Nucleic acid extraction was performed using the ThermoFisher KingFisher FLEX instrument with MagMAX Viral/Pathogen Nucleic Acid Isolation reagents. Amplification was performed using the Applied Biosystems™ 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR Systems (SDS v1.5.1) with TaqPath 1-step RT-qPCR master mix CG reagents. For quantification, a standard curve was used by amplifying 10-fold serial dilutions (75 copies/mL to 7.5 × 107 copies/mL) of in vitro transcribed RNA prepared from the full SARS-CoV-2 N gene. Copies/mL for each sample generating a cycle threshold (Ct) value calculated using the slope and y-intercept derived from linear regression of the standard curve results. The limit of detection for this assay is 75 copies/mL; in this study Ct values <40 were reported as the calculated copies/mL.

3. Results

3.1. Donor antibodies

Of the 139 donors, 114 (82 %) had IgG antibodies >1.0 AU/mL (Table 1 ). The median number of days from first positive test was 32 days for the IgG > 1.0 compared to 43 days for those with IgG < 1.0 (p = 0.09). Seventy-five of the 114 donors had IgG antibodies > 6.5 AU/mL, which corresponds with a IgG antibody titer of about 1:320 (https://ccpp19.org/healthcare_providers/virology/antibodies.html), the minimum level recommended by FDA at the time of this study (subsequently lowered to 1:160) [4]. Of those, 50 had IgG >20, corresponding to IgG antibody titer of 1:1000.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 139 convalescent plasma donors.

| All Potential Donors | IgG Positive (>1.0 AU/mL) | Eligible Donors (IgG>6.5 AU/mL) | Donated Plasma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 139 | n = 114 | n = 75 | n = 29 | |

| Gender, Female, n (%) | 75 (54.0) | 64 (56.1) | 41 (54.7) | 17 (58.6) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.8 (14.5) | 49.8 (14.4) | 51.7 (13.3) | 49.9 (14.6) |

| Race. n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 4 (2.9) | 3 (2.6) | 2 (2.7) | 1 (3.5) |

| Black/African American | 9 (6.5) | 8 (7.0) | 8 (10.7) | 3 (10.3) |

| Hispanic | 16 (11.5) | 15 (13.2) | 9 (12.0) | 3 (10.3) |

| Other/Unknown | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (1.3) | 0 |

| White | 106 (76.3) | 86 (75.4) | 55 (73.3) | 22 (75.9) |

| Days, positive test to symptom resolution, mean (SD) | 10.0 (±6.7) | 10.1 (±6.9) | 9.6 (±6.1) | 9.5 (±4.2) |

| Days, positive test to negative test, mean (SD) | 35.4 (11.0) | 34.6 (10.6) | 33.5 (10.7) | 29.8 (6.8) |

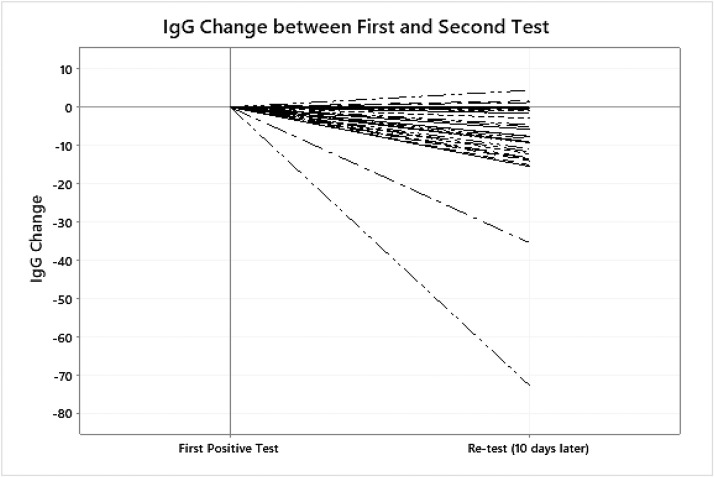

46/114 potential donors tested positive a second time when screened for COVID. Thirty-seven retested 10 days later, and 14 remained positive a third time. One person tested positive a fourth time. Among those tested at least twice, we noted a drop in median IgG of 8 AU/mL (p < 0.01) in the days between tests (≈10 days). During the 10 days between tests, the median IgG decreased from 21.2 AU/mL to 13.1 AU/mL (p < 0.01). There was no correlation between age and change in the IgG levels. Fig. 1 shows the change in IgG from first to second test. Antibody data was available for 10 of the 14 who remained positive after another 10 days, and the median IgG decreased again. (Table 2 )

Fig. 1.

IgG change in donors re-tested.

Table 2.

Change in IgG among eligible convalescent plasma donors who were re-tested for SARS-CoV-2.

| IgG (AU/mL) time 1 |

IgG (AU/mL) time 2 |

IgG (AU/mL) time 3 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | *p-value | |

| Donors tested twice (n = 37) | 30.4 (29.7) | 21.2 (4.7–51.7) | 22.7 (25.5) | 13.1 (3.9–30.3) | NA | NA | <0.01 |

| Donors tested 3 times (n = 10) | 35.5 (25.0) | 35.4 (8.6–54.4) | 27.1 (19.6) | 24.3 (6.9–42.7) | 23.4 (20.1) | 18.8 (5.6–42.8) | 0.63 |

Compares value at time 1 and last measured value.

Of the 75 donors with adequate IgG antibodies, plasma was collected by apheresis from 29 eligible donors. Plasma (400–800 mL) collected from each donor depending on age and body weight, and prepared and stored as 200 mL aliquots.

3.2. Recipient antibodies

Forty-six patients with severe or life threatening disease with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection enrolled in the study between April 21, 2020, and Jun 8, 2020. Seven patients received plasma with insufficient antibodies and excluded from the analysis. One patient included in this study developed a transfusion reaction after receiving one unit and did not receive second unit. The average duration between positive test and receiving convalescent plasma was 11.4 days.

Table 3 shows the blood types of recipients compared to the national percentages. A significantly higher proportion of recipients had blood type O + compared to the national numbers (p < 0.01). No differences in antibody levels by blood type.

Table 3.

Distribution of ABO/Rh blood types of convalescent plasma recipients compared to the US population.

| ABO/Rh Blood Group | Recipients, no. (%) | United States Population* (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| O positive | 25 (64) | 38 | <0.01 |

| O negative | 1 (26) | 7 | 0.37 |

| A positive | 10 (26) | 34 | 0.31 |

| B positive | 3 (8) | 9 | 0.80 |

© 2020 The American National Red Cross.

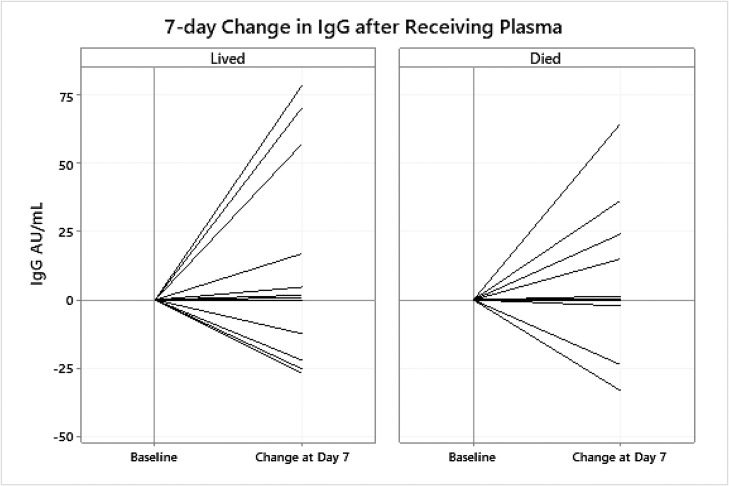

39 patients had blood collected on day 0 (pre-transfusion), and on post-transfusion day 3 (n = 36), 5 (n = 30), and 7 (n = 24) and plasma viral load and serum antibody titers was assessed at each time point (Table 4 ). 28/39 (71.8 %) had positive values of serum IgM at baseline with a median 3.0 AU/mL. 24/39 (61.5 %) patients had IgM values on day 7 of which 22/24 (91.7 %) were IgM positive. Similarly, at baseline 26 of the 39 (66.7 %) patients had positive IgG (median = 54.8 AU/mL). Among the 24 with day 7 IgG values, 21 were positive with a median IgG of 66.2 AU/mL (Fig. 2 ). Changes from day 0 to day 7 in recipient IgG antibodies ranged from a decrease of –33.3 AU/mL to an increase of 78.8 AU/mL, with a median increase of 0.47 AU/mL. Fig. 2 shows the percent change from day 0 to day 7 for 24 patients with day 7 data.

Table 4.

Median IgM and IgG values in patients before and after receiving convalescent plasma.

| Time | IgM (AU/mL) Median (25th–75th percentile) | IgG (AU/mL) Median (25th–75th percentile) |

|---|---|---|

| Day 0 (n = 39) | 2.1 (1.0–3.9) | 18.5 (<1.0–75.0) |

| Day 3 (n = 36) | 3.1 (1.7–4.6) | 37.2 (4.5–74.6) |

| Day 5 (n = 30) | 2.9 (1.5–4.1) | 47.4 (6.7–80.7) |

| Day 7 (n = 24) | 2.8 (1.7–5.0) | 55.2 (10.3–96.9) |

Fig. 2.

7 day change in IgG in recipients of convalescent plasma.

3.3. Viral load

Plasma viral load data was available for 35 or the 39 convalescent plasma recipients on day 0. Twenty-two patients (62.9 %) had non-detectable levels (<75 copies/mL). Of the 13 with detectable levels, viral loads ranged from 95 to 53,622 copies/mL. On day 7, data on plasma viral load were available for only 7 of the 13. Of those, 4 (57.1 %) still had detectable viral loads. (Table 5 ). The time from testing positive was related to the viral load. Patients with non-detectable viral load had a mean of 14.5 (SD ± 9.6) days since their first positive test compared to a mean of 6.2 (±4.7) days for the group with detectable viral load (p < 0.01). In contrast, there was no relationship between viral load and blood type (p = 0.87) or death (p = 0.80).

Table 5.

Viral load over time in patients receiving convalescent plasma.

| Time | No Detectable Virus (<75 copies/mL), no. (%) | Viral Load (copies/mL) Median (25th - 75th Percentile) |

|---|---|---|

| Day 0 (n = 35) | 22 (62.9) | 3524 (868–8315), n = 13 |

| Day 3 (n = 34) | 25 (73.5) | 2033 (243–6386), n = 9 |

| Day 5 (n = 27) | 20 (74.1) | 315 (214–4162), n = 7 |

| Day 7 (n = 24) | 20 (83.3) | 494 (102–1292), n = 4 |

IgG antibody levels were related to viral load. On days 0, 3, 5, and 7, IgG levels were higher among patients a non-detectable viral load compared to patients with a detectable viral load. On day 0, IgM antibody levels were higher in the group with a no detectable viral load (p < 0.01). However, differences in IgM antibody levels between patients with and without detectable viral load on days 3, 5, and 7 were not statistically significant.

Of the 39 patients,19 (49 %) died, and 20 (51 %) were discharged. There were no significant differences in IgM (p > 0.10) between patients who died and patients who lived at any time-point. In contrast, the median IgG at day 5 was lower in those who died (10.4 AU/mL vs. 66.2 AU/mL, p = 0.05). Though not statistically significant (p = 0.22), IgG was lower at day 7 in patients who died (33.6 AU/mL vs. 71.1 AU/mL). There was no difference in the median number of days between testing positive and receiving plasma among those who died and those discharged.

4. Discussion

Passive antibody therapy involves administration of antibodies against a given agent to a susceptible individual for the purpose of preventing or treating an infectious disease. Protective specific antibodies like IgG produced by B cells after infection with the virus, help block the virus from entering the host cells, as well as defend against viral reinfection. SAR-CoV-2 virus is enveloped with four structural proteins which serve as targets for antibodies [11,20,21], and uses its spike glycoprotein, a main target for neutralization antibody, to bind its receptor and mediate membrane fusion and virus entry [21]. The hypothesis is that administration of convalescent plasma containing such antibodies may mediate viral neutralization [22] by inhibiting viral replication and blunting pro-inflammatory endogenous antibody response [23].

For passive antibody therapy to be effective, a sufficient amount of antibody must be administered [16]. Although we did not measure neutralizing antibodies, high levels of IgG correlate with high levels of neutralizing antibodies in serum [24]. The criteria used for this study, IgG ≥6.5 AU/mL, corresponds to a IgG antibody titer of about 1:320, the minimum level recommended by FDA at the time of this study (subsequently lowered to 1:160) [4]. Currently enzyme linked immunoassays and chemiluminescence assays are used to detect IgG and IgM antibodies against recombinant N and S proteins of SARS-CoV-2 [25].

FDA guidance for donors of convalescent plasma is evidence of COVID-19 documented by a diagnostic test like the nasopharyngeal swab at the time of illness, or a positive serological test for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies after recovery if prior diagnostic testing not performed. The other criterion is complete resolution of symptoms at least 14 days before plasma donation. A negative result for COVID-19 by a diagnostic test is not necessary to qualify the donor [4]. Potential donors in our study reported that symptom resolution took almost 10 days from symptom onset, with an average of 35 days from positive to negative test. However 25 (18 %) potential donors had negative IgG levels (<1.0 AU/mL). We did find that 46 of 114 eligible donors (those with a positive IgG level) still tested positive by nasopharyngeal swab (qualitative) in spite of being asymptomatic for >2 weeks. All donors had viral load measured in plasma and all had undetected viral load. In our study, we measured viral load in plasma and not nasopharyngeal swabs, but results are similar to findings from a recent investigation in South Korea showing that the virus was not present in respiratory samples from 108 patients who had re-tested positive after recovery [27]. However, during the 10 days between tests, median IgG levels decreased. (Table 2, Fig. 1) These data suggests that some individuals do not mount a sufficient response or that antibodies decline quickly over time.

We found a majority of our plasma recipients were blood group O+ (64 %), significantly more than the proportion of O + individuals in the general US population. This was contrary to studies were the odds of COVID-19 infection is higher in blood groups A and decreased in blood groups O [28]. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but warrants further investigation. Our analysis is limited based on the small sample size and non-randomized design, and we cannot say with any certainty that our findings reflect the general population or COVID-19 patients specifically.

Studies have shown an increase in viral load in the early and progressive stages of infection and a decrease in the recovery stage [29]. We found a relationship in duration from first testing positive for virus by nasopharyngeal swab (rRT-PCR) to the presence of plasma viral load. Patients with non-detectable viral load levels had a mean of 14.5 days since their first positive test compared to 6.2 days for the group with detectable levels (p < 0.01). However, we had large variation in the number of days from positive test to receipt of plasma (4 days to 34 days). Studies have reported that a peak in viral load coincides with onset of antibodies and that higher concentration of antibodies leads to higher levels of virus-induced apoptosis [30] however, there is no abrupt virus elimination at the time of seroconversion rather a slow but steady decline of viral load has been reported [31]. We found that the group with non-detectable viral load had slightly increased antibodies over the 7 days compared to the group with detectable viral load. There is a link between viral load and other biochemical markers like interleukin-6 (IL-6) to disease severity and poorer prognosis [[31], [32], [33]]. Of the 39 patients, 49 % died, 51 % discharged. Even though there were no significant differences in IgM at any time-point the median IgG at day 5 was lower in those who died. Overall, there was no difference in the median number of days between testing positive and receiving plasma among those who died and those discharged nor was there a relationship between plasma viral load and blood type.

This study has limitations. We conducted a non-randomized study with a small sample size at an urban teaching hospital under “real-world” conditions. Although we recorded data over time, the study would have been stronger if we had measured plasma viral load at onset of hospitalization. Further SARS-Co-V-2 is not a blood-borne pathogen and nasopharyngeal samples may have given more accurate viral load. However, our data may inform future studies. We also found no significant relationship between plasma viral load and mortality among recipients, which may be due to the time of testing.

5. Conclusion

We found that the average time that donors remained symptomatic was ≈10 days, however the majority of them still tested positive for the virus by nasopharyngeal swab 36 days after symptom onset but did not have detectable plasma viral load when measured at the same time point. As for antibodies, a significant number of potential donors with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection were negative for IgG antibodies at a median of 43 days after onset of symptoms. In those with positive antibodies we saw a significant decline in IgG levels over time. This is suggestive that having had the infection does not necessarily convey immunity, or there is a short duration of immunity associated with a decline in antibodies. As for the recipients, there was no correlation to the number of days from having tested positive to receiving convalescent plasma. We also found lower IgG levels in those with a detectable plasma viral load and there was no relationship between plasma viral load, blood type or death.

Funding sources

This study was supported by funds from Trinity Health Of New England, a not-for-profit healthcare organization.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Latha Dulipsingh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Visualization. Danyal Ibrahim: Funding acquisition, Project administration. Ernst J. Schaefer: Visualization, Resources, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. Rebecca Crowell: Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - review & editing, Visualization. Margaret R. Diffenderfer: Resources, Formal analysis. Kendra Williams: Investigation, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Colleen Lima: Data curation. Jessica McKenzie: Investigation, Data curation. Lisa Cook: Investigation, Data curation. Jennifer Puff: Investigation, Data curation. Mary Onoroski: Resources, Investigation. Dorothy B. Wakefield: Formal analysis, Data curation, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Reginald J. Eadie: Resources. Steven B. Kleiboeker: Resources, Investigation. Patricia Nabors: Resources, Investigation. Syed A. Hussain: Funding acquisition, Resources.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Christopher Hillyer from New York Blood Center and Rhode Island Blood Center for assisting with the plasma collection process; Kelly Batch, Donna Sobinski, Cynthia Considine, Brian Masthay, Christina Maxwell and Robert W. Wilke from the Trinity Health Of New England EPIC team for helping with the study build and support; Phillip Roland, Paul Porter, Robert Roose, Ian Tucker, Daniel Geradi, Prashant Grover, Gagandeep Singh, Bethel Shiferaw, Jason Ouellette, Vikram Sondhi, Laurie Loiacono, and Richard Levarault for their help in enrolling recipients; and Karen Blank and Kartik Natarajan for reviewing the manuscript and for their editorial comments.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 66. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200326-sitrep-66-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=9e5b8b48_2. 2020 March 26 (cited 2020 15 June).

- 2.Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. COVID-19 global cases (cited 2020 Aug 6). https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html.

- 3.Barlow A., Landolf K.M., Barlow B., Yeung S.Y.A., Heavner J.J., Claassen C.W. Review of Emerging Pharmacotherapy for the Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Pharmacotherapy. 2020;40(5):416–437. doi: 10.1002/phar.2398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Food and Drug Administration . 2020. Investigational COVID-19 convalescent plasma: emergency INDs.https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/investigational-new-drug-ind-or-device-exemption-ide-process-cber/investigational-covid-19-convalescent-plasma-emergency-inds (accessed 2020 March 30; guidance updated 2020 May 1) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou B., Zhong N., Guan Y. Treatment with convalescent plasma for influenza A (H5N1) infection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(14):1450–1451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc070359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hung I.F., To K.K., Lee C.K., Lee K.L., Chan K., Yan W.W. Convalescent plasma treatment reduced mortality in patients with severe pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(4):447–456. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burnouf T., Radosevich M. Treatment of severe acute respiratory syndrome with convalescent plasma. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9(4):309. ; author reply 10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng Y., Wong R., Soo Y.O., Wong W.S., Lee C.K., Ng M.H. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in SARS patients in Hong Kong. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;24(1):44–46. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1271-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mair-Jenkins J., Saavedra-Campos M., Baillie J.K., Cleary P., Khaw F.M., Lim W.S. The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2015;211(1):80–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun M., Xu Y., He H., Zhang L., Wang X., Qiu Q. Potential effective treatment for COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis of the severe infectious disease with convalescent plasma therapy. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.107. (cited 2020 July 30). Epub 2020 July4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li L., Tong X., Chen H., He R., Lv Q., Yang R. Characteristics and serological patterns of COVID-19 convalescent plasma donors: optimal donors and timing of donation. Transfusion. 2020;(July (6)) doi: 10.1111/trf.15918. 10.1111/trf.15918. doi: 10.1111/trf.15918. Epub ahead of print. (cited 2020 July 30) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Long Q.X., Tang X.J., Shi Q.L. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Med. 2020;26(August (8)):1200–1204. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0965-6. Epub 2020 Jun 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen C., Wang Z., Zhao F. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA. 2020;323(16):1582–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4783. [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 27] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Psaltopoulou T., Sergentanis T.N., Pappa V., Politou M., Terpos E., Tsiodras S. The emerging role of convalescent plasma in the treatment of COVID-19. Hemasphere. 2020;4(3):e409. doi: 10.1097/HS9.0000000000000409. Published 2020 May 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang B., Liu S., Tan T. Treatment with convalescent plasma for critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. Chest. 2020;158(1):e9–e13. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan K., Liu B., Li C. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(17):9490–9496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004168117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye M., Fu D., Ren Y., Wang F., Wang D., Zhang F. Treatment with convalescent plasma for COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.25882. (cited 2020 June 15) Epub 2020 April 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L., Pang R., Xue X., Bao J., Ye S., Dai Y. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 virus antibody levels in convalescent plasma of six donors who have recovered from COVID-19. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12(8):6536–6542. doi: 10.18632/aging.103102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn J.Y., Sohn Y., Lee S.H. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in two COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(14):e149. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e149. Published 2020 Apr 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan R., Zhang Y., Li Y., Xia L., Guo Y., Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020;367(6485):1444–1448. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2762. (cited 2020 June 15). Epub 2020/03/04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ou X., Liu Y., Lei X., Li P., Mi D., Ren L. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):1620. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9. (cited 2020 July 30). Epub 2020 March 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casadevall A., Pirofski L.A. The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(4):1545–1548. doi: 10.1172/JCI138003. Apr 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tiberghien P., de Lamballerie X., Morel P., Gallian P., Lacombe K., Yazdanpanah Y. Collecting and evaluating convalescent plasma for COVID-19 treatment: why and how? Vox Sang. 2020 doi: 10.1111/vox.12926. 10.1111/vox.12926. doi:10.1111/vox.12926 (cited 2020 June 6) Epub 2020/04/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.To K.K., Tsang O.T., Leung W.S., Tam A.R., Wu T.C., Lung D.C. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(5):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong L., Chuan J., Gong B.O., Shuai P., Zhou Y., Zhang Y. Detection of serum IgM and IgG for COVID-19 diagnosis. Sci China Life Sci. 2020;63(May 5):777–780. doi: 10.1007/s11427-020-1688-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korean Centers for Disease Control (press release) Findings from investigation and analysis of re-positive cases; 2020 May 21 (cited 2020 June 6). https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a30402000000&bid=0030&act=view&list_no=367267&nPage=6.

- 28.Zietz M., Tatonetti N.P. Testing the association between blood type and COVID-19 infection, intubation, and death. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19623-x. [Preprint]. 2020 Apr 11:2020.04.08.20058073. doi: 10.1101/2020.04.08.20058073. (cited 2020 June 20) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu F., Yan L., Wang N., Yang S., Wang L., Tang Y. Quantitative detection and viral load analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(15):793–798. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng S., Fan J., Yu F., Feng B., Lou B., Zou Q. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January-March 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ Epub. 2020;21(April (369)):m1443. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1443. (cited 2020 June 16) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Zange S. Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581(May 7809):465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen X., Zhao B., Qu Y., Chen Y., Xiong J., Feng Y. Detectable serum SARS-CoV-2 viral load (RNAaemia) is closely correlated with drastically elevated interleukin 6 (IL-6) level in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;(April (17)):ciaa449. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa449. (cited 2020 June 16) Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lescure F.X., Bouadma L., Nguyen D., Parisey M., Wicky P.H., Behillil S. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(6):697–706. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20). [published correction appears in Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 May 19;:] [published correction appears in Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jun;20(6):e116] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]