Abstract

A mild visible-light-induced Pd-catalyzed intramolecular C–H arylation of amides is reported. The method operates by cleavage of a C(sp2)–O bond, leading to hybrid aryl Pd-radical intermediates. The following 1,5-hydrogen atom translocation, intramolecular cyclization, and rearomatization steps lead to valuable oxindole and isoindoline-1-one motifs. Notably, this method provides access to products with readily enolizable functional groups that are incompatible with traditional Pd-catalyzed conditions.

Keywords: homolysis, light-mediated reactions, palladium, radicals, triflates

Aryl halides are essential substrates for a variety of Pd-catalyzed transformations, which traditionally rely on the PdII intermediates formed by a two-electron oxidative-addition process.[1] Recently, a new approach involving intermediacy of a PdI species generated by a single-electron-transfer (SET) step from a photoexcited Pd0 complex to an organohalide, emerged as a powerful and rapidly expanding area of Pd catalysis.[2] Recently, our group reported visible-light-induced Pd-catalyzed cleavage of the C(sp2)–I bond of aryl iodides, leading to formation of aryl hybrid Pd-radical intermediates A (Scheme 1a).[3] The latter underwent a selective 1,5-hydrogen atom translocation step (HAT)[4] (B) followed by β-H elimination, leading to silyl enol ethers[3] and desaturated amines[5] in an efficient manner. This strategy was also successfully translated to the fragmentation of C(sp2)–I bonds of vinyl iodides, leading to the formation of vinyl hybrid Pd-radical intermediates.[6] Notably, these novel methods[7] rely on the employment of organic halides,[8] predominantly iodides and bromides, which limits the synthetic applicability of this approach. Potential employment of alternative aryl electrophiles would substantially expand the variety of available substrates for these transformations. Herein, we report mild visible-light-induced[9] palladium-catalyzed fragmentation of C(sp2)–O bonds of aryl trifluorome thanesulfonates (triflates) 1,[10] leading to the formation of aryl hybrid Pd-radicals A1.[11] The latter, upon sequential 1,5-HAT (A1→B1 [12]), intramolecular cyclization, and rearomatization steps, provided valuable oxindole products 2 (Scheme 1b).[13]

Scheme 1.

Aryl iodides and triflates in visible-light-induced Pd-catalyzed transformations. T= Tether.

Encouraged by the successful cleavage of aryl halides,[3,5,14] and inspired by work from the Li group[15] on UV-light-induced transition-metal-free fragmentation of (Csp2)–O bonds [Eq. (1)], we set to investigate the feasibility of generating hybrid aryl Pd-radical intermediates from aryl triflates under visible-light/Pd conditions.

|

(1) |

The intramolecular coupling of aryl triflates 1 was chosen for this study. Hartwig and co-workers[16] reported intramolecular α-arylation of amides as a powerful approach towards the construction of oxindole cores.[13b,c,d] Although high yielding and enantioselective, this method relies on the employment of strong bases, which notably diminishes the scope of this approach.

We began our study with examination of the intramolecular α-arylation of triflate 1a (Table 1). Previously optimized reaction conditions proved to be inefficient (entry 1),[3] however, we found that oxindole 2a could be formed in low yield in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) when the bis[(2-diphenylphosphino)phenyl] ether (dpephos) ligand was employed. Further optimization revealed that this intramolecular arylation proceeds better in the presence of NaI (entry 3). Extensive ligand screening found 2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binapthanlene (rac-BINAP) to be a superior ligand, leading to oxindole 2a in 41% yield. Screening other additives, known to affect Pd-catalyzed transformations of aryl triflates by stabilization of oxidative-addition adducts,[17] did not lead to an improvement in the reaction (entries 5 and 6). Optimization of the solvent indicated that this reaction proceeds best in 1,4-dioxane, leading to the oxindole 2a in 62% yield. Control experiments confirmed that catalyst, light, and additive are all essential for the success of this transformation (entries 8, 9). Additionally, performing the reaction in the presence of radical scavenger 2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidine 1-oxyl (TEMPO; entry 10) led to a substantially diminished yield, thus indicating the possible involvement of radical intermediates.

Table 1:

Optimization of reaction parameters.[a]

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ligand | Additive | Solvent | Yield [%][b] |

| 1[c,d] | dtbdppf | - | benzene | 0 |

| 2 | dpephos | - | DMF | 11 |

| 3 | dpephos | Nal | DMF | 30 |

| 4 | rac-BINAP | Nal | DMF | 41 |

| 5 | rac-BINAP | NaCI | DMF | 18 |

| 6 | rac-BINAP | NaOAc | DMF | 19 |

| 7 | rac-BINAP | Nal | 1,4-dioxane | 62 |

| 8[e] | rac-BINAP | Nal | 1,4-dioxane | <1 |

| 9[f] | rac-BINAP | Nal | 1,4-dioxane | <1 |

| 10[g] | rac-BINAP | Nal | 1,4-dioxane | 5 |

All reactions were performed on a 0.1 mmol scale.

GC–MS yield.

2 equivalents of Cs2CO3 were used.

1-Diphenylphosphino-1′-(di-tert-butylphosphino)ferrocene.

No Pd(OAc)2 was added.

No light, T= rt to 100°C.

2 equivalents of TEMPO were added.

With the optimized conditions in hand, the scope of this intramolecular arylation reaction towards the oxindole core[18] was studied (Table 2). Thus, reaction of triflate 1a led to the oxindole 2a in 60% yield. Introduction of various alkyl groups next to α-carbon atom posed no problem, leading to oxindoles 2b–2d in 61, 65, and 69% yield, respectively. Substrates 1e–1g, which have halo- and ester functional groups on the aromatic ring, reacted well to provide products 2e–2g in good yields. Likewise, tricyclic oxindole 2h was obtained in 64% yield. Alkyl substituents on the aryl ring were also tolerated. The scope of this transformation could further be expanded to spirocyclic oxindole motifs. Thus, spiro cyclopropyl- (2k), cyclobutyl- (2l), cyclopentyl- (2m), and cyclohexyl- (2n) oxindoles were synthesized efficiently by using this protocol. Norbornane derivative 1o reacted smoothly leading to 2o in 70% yield. Incorporation of heteroatoms did not alter the course of the reaction to give oxindoles 2p–2r in 85, 65, and 66% yield, respectively. Notably, base-sensitive functionalities, such as ketone and ester groups are well tolerated under these reaction conditions. Thus, oxindoles 2s and 2t, possessing enolizable groups and thus, unavailable via traditional Pd-catalyzed methods,[13,16] were isolated in 50 and 71% yield, respectively. The transformation of cyclopentene derivative 1u led to the corresponding oxindole 2u, albeit in moderate yield. Varying the substitution pattern at the N atom led to oxindoles 2v–2x in 71, 59, and 57% yield, respectively. Notably, this transformation was capable of delivering the 3-monosubstituted oxindole 2y, though in a moderate 40% yield. However, the replacement of the bulky tert-butyl group with the sterically less demanding n-pentyl moiety led to formation of acyclic desaturated amide 2z′ as the major reaction product.

Table 2:

Scope of oxindoles.[a]

|

Reaction conditions: 1 0.1 mmol, Pd(OAc)2 0.01 mmol, rac-BINAP 0.02 mmol, NaI 0.2 mmol, Cs2CO3 0.125 mmol, 1,4-dioxane 0.1m, 34 W blue LED.

NMR yield.

α:β, 3:1.

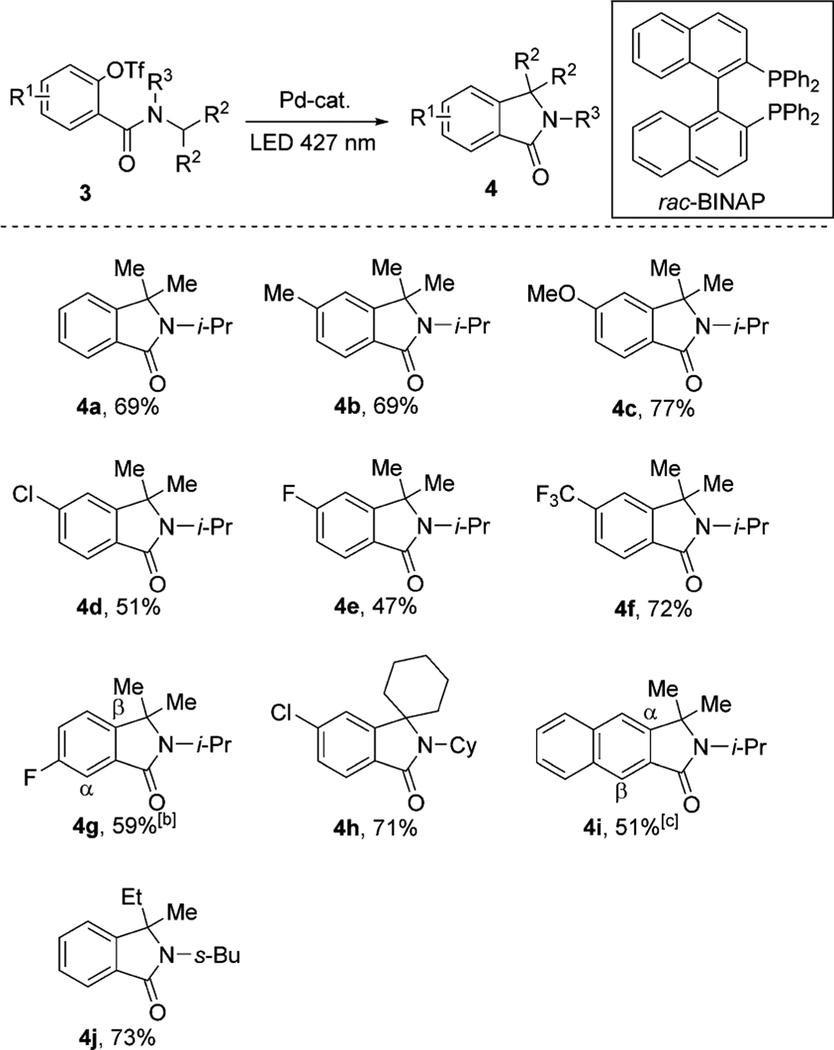

Notably, the developed method for the synthesis of oxindoles 2 operates under an electronically matched scenario, in which a translocated electrophilic radical B1 cyclizes at an electron-rich aromatic ring (Scheme 1b). We hypothesized that the analogous cyclization under an electronically inversed scenario (A2→B2) should be possible, thus leading to useful isoindoline-1-one products 4.[19] Therefore, the cyclization of benzamide[20] 3a was tested under the optimized reaction conditions. To our delight, isoindoline-1-one 4a was isolated in 69% yield (Table 3). Reactions of differently substituted benzamides (3b–g, 3i), featuring alkyl, methoxy, halo-, trifluoromethyl, and naphthyl groups proceeded smoothly, providing the corresponding isoindoline-1-ones in moderate-to-good yields. The protocol also proved to be efficient for the cyclization of cyclohexyl- and isobutyl amides, leading to products 4h and 4j in 71 and 73% yield.

Table 3:

Scope of isoindoline-1-ones.[a]

|

Reaction conditions: 1 0.1 mmol, Pd(OAc)2 0.01 mmol, rac-BINAP 0.02 mmol, NaI 0.2 mmol, Cs2CO3 0.125 mmol, 1,4-dioxane 0.1m, 40 W blue LED.

α:β, 2.5:1.

α:β, 2:1.

Next, we turned our attention to the mechanism of this intramolecular C–H arylation reaction. As mentioned above (Table 1, entry 10), the reaction was sensitive to the presence of a radical scavenger, leading to a dramatic decrease of the reaction yield. Additional evidence supporting the radical nature of this transformation was obtained by the following deuterium-labeling experiments [Eq. (2)]. Intramolecular arylation of deuterated triflate 1a-D was investigated first. It was expected that upon fragmentation of the C–O bond and subsequent 1,5-HAT, the B1-D intermediate would be produced. In the absence of any stereoelectronic factors, this intermediate was expected to display equal probability for

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

cyclization at either the C2- or C6-position of the aromatic ring, thus leading to the oxindole 2a-D with a statistical preservation of the deuterium label at about 47%. Indeed, experiments with triflate 1a-D completely supported the above projections, leading to the oxindole 2a-D with 48% deuterium incorporation at the aromatic ring. Furthermore, cyclization of the alternatively D-labeled triflate, 1a′-D, reacting via the same intermediate, B1-D, was examined, and was found to produce the single reaction product oxindole 2a-D. As in the previous experiment, an excellent agreement between the predicted and observed levels of deuterium-label incorporation was observed. These deuterium-labeling experiments ruled out a potential direct C–H activation mechanism (1a′-D→i→2a-D),[21] according to which a complete preservation of the deuterium label at the C2-position should be observed [Eq. (3)].

In addition, the radical nature of this transformation was further confirmed by a radical-clock experiment with triflate 1aa producing the ring-opened dienamide 2aa [Eq. (4)], and by the spin-trap experiments with 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO).[22]

Based on the preliminary mechanistic studies, we postulate the formation of a key hybrid aryl Pd-radical intermediate A1 in this transformation (Scheme 2). A consecutive 1,5-HAT step produces the translocated hybrid alkyl radical B1, which, upon intramolecular cyclization at the aromatic ring (C1) and a subsequent rearomatization, is converted to the oxindole product 2a. At present, the details of the C–O-bond-fragmentation step, as well as the precise role of NaI, remain unclear. We foresee the generation of intermediate A1 via several alternative scenarios. According to path A, a SET between aryl triflate 1a and an active photoexcited Pd complex[23] leads to the formation of an aryl triflate radical anion (not shown), which upon cleavage of the C–O bond leads to A1. In path B, oxidative addition of the Pd catalyst onto 1a leads to the adduct D1, which then undergoes visible-light-induced homolysis of the C–Pd bond, thus leading to A1. Alternatively, ligand exchange between D1 and NaI results in a more stable aryl–Pd–I intermediate E1. [17] As in the previous case, irradiation-induced homolysis of the C–Pd bond converts E1 into A1 (path C). Finally, a reductive elimination of the intermediate E1 generates aryl iodide 5. The latter undergoes SET with the photoexcited Pd catalyst,[3,5] leading to hybrid aryl Pd-radical A1 (path D). It should be mentioned that several additional mechanistic experiments, including an EPR study on model substrates, rate comparison of stoichiometric reactions with palladium, and monitoring parallel reactions at the early stages, suggest that all four scenarios are feasible.[22] Accordingly, at this stage, none of the proposed pathways for fragmentation of the C–O bond may be reliably ruled out. Evidently, more detailed mechanistic studies are required to understand the precise mechanism for this novel transformation.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism. OA= Oxidative addition; RE= reductive elimination.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the combination of visible light and palladium catalysis can efficiently fragment the C(sp2)–O bond of readily available aryl triflates, leading to aryl hybrid Pd radicals. Involvement of these radicals in successive 1,5-HAT, cyclization, and rearomatization events afforded diversely substituted oxindole and isoindoline-1-one products. Advantageous engagement of a Pd0/PdI/PdII manifold over the traditional Pd0/PdII cycle allowed for the formation of oxindole products with base-sensitive functionalities that are incompatible with traditional Pd-catalyzed conditions. Although, the involvement of hybrid Pd radicals is well supported, the details of the C–O-bond-fragmentation step, as well as the role of NaI, remain unclear at this stage. More detailed mechanistic studies are required to elucidate the precise mechanism of this transformation. It is believed that this method will find applications in synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM120281), National Science Foundation (CHE-1936422), and Welch Foundation (Chair, AT-0041). We thank Prof. Anvar Zakhidov (UTD) and Dr. Alexios Paradimitratos (UTD) for the help with EPR experiments.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Maxim Ratushnyy, Department of Chemistry,University of Illinois at Chicago 845 W. Taylor Street, Chicago, IL 60607-7061 (USA); Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 West Campbell, BSB13, Richardson, TX 75080 (USA).

Nikita Kvasovs, Department of Chemistry,University of Illinois at Chicago 845 W. Taylor Street, Chicago, IL 60607-7061 (USA); Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 West Campbell, BSB13, Richardson, TX 75080 (USA).

Sumon Sarkar, Department of Chemistry,University of Illinois at Chicago 845 W. Taylor Street, Chicago, IL 60607-7061 (USA); Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 West Campbell, BSB13, Richardson, TX 75080 (USA).

Vladimir Gevorgyan, Department of Chemistry,University of Illinois at Chicago 845 W. Taylor Street, Chicago, IL 60607-7061 (USA); Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 West Campbell, BSB13, Richardson, TX 75080 (USA).

References

- [1].For selected reviews on Pd-catalyzed reactions, see:; a) Negishi E in Handbook of Organopalladium Chemistry for Organic Synthesis, Wiley, Chichester, 2003; [Google Scholar]; b) De Meijere A, Diederich F in Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions, 2nd ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004, p. 815; [Google Scholar]; c) Selander N, Szabó KJ, Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 2048; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Molnár A, Chem. Rev 2011, 111, 2251; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Johansson Seechurn CCC, Kitching MO, Colacot TJ, Snieckus V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2012, 51, 5062; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Chuentragool P, Kurandina D, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 11586; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 11710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Parasram M, Chuentragool P, Sarkar D, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 6340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].For selected examples of the hydrogen-atom-translocation (HAT) step, see:; a) Stateman LM, Nakafuku KM, Nagib DA, Synthesis 2018, 50, 1569; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Stateman LM, Wappes EA, Nakafuku KM, Edwards KM, Nagib DA, Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 2693; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang Z, Stateman LM, Nagib DA, Chem. Sci 2019, 10, 1207; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Green SA, Matos JLM, Yagi A, Shenvi RA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12779; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Green SA, Crossley SWM, Matos JLM, Vasquez-Cespedes S, Shevick SL, Shenvi RA, Acc. Chem. Res 2018, 51, 2628; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Voica A-F, Mendoza A, Gutekunst WR, Otero Fraga J, Baran PS, Nat. Chem 2012, 4, 629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Chuentragool P, Parasram M, Shi Y, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ratushnyy M, Parasram M, Wang Y, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 2712; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].For examples of visible-light-induced Pd-catalyzed transformations of alkyl halides, see:; a) Parasram M, Chuentragool P, Wang Y, Shi Y, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 14857; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kurandina D, Parasram M, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 14212; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 14400; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kurandina D, Rivas M, Radzhabov M, Gevorgyan V, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 357; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Chuentragool P, Yadagiri D, Morita T, Sarkar S, Parasram M, Wang Y, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 1794; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 1808; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Wang G-Z, Shang R, Cheng W-M, Fu Y, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 18307; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kancherla R, Muralirajan K, Maity B, Zhu C, Krach PE, Cavallo L, Rueping M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2019, 58, 3412; Angew. Chem. 2019, 131, 3450; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Zhou W-J, Cao G-M, Shen G, Zhu X-Y, Gui Y-Y, Ye J-H, Sun L, Liao L-L, Li J, Yu D-J, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2017, 56, 15683; Angew. Chem. 2017, 129, 15889; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Jiao Z, Lim LH, Hirao H, Zhou JS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 6294; Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 6402; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i) Wang G-Z, Shang R, Fu Y, Synthesis 2018, 50, 2908; [Google Scholar]; j) Sun L, Ye J-H, Zhou W-J, Zeng X, Yu D-G, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].For examples of visible-light-induced Pd-catalyzed transformations of alkyl redox-active esters, see:; a) Koy M, Sandfort F, Tlahuext-Aca A, Quach L, Daniliuc CG, Glorius F, Chem. Eur. J 2018, 24, 4552; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang G-Z, Shang R, Fu Y, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 888; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Cheng WM, Shang R, Fu Y, Nat. Chem 2018, 9, 5215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].For selected reviews, see:; a) Prier CK, Rankic DA, MacMillan DWC, Chem. Rev 2013, 113, 5322; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Skubi KL, Blum TR, Yoon TP, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 10035; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Romero NA, Nicewicz DA, Chem. Rev 2016, 116, 10075; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Xie J, Jin H, Hashmi ASK, Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 5193; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Parasram M, Gevorgyan V, Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 6227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].For selected examples of Pd0/PdII-catalyzed reactions of aryl triflates, see:; a) Ritter K, Synthesis 1993, 735; [Google Scholar]; b) Carmona JA, Hornillos V, Ramirez-Lopez P, Ros A, Iglesias-Siguenza, Gomez-Bengoa E, Fernandez R, Lassaletta JM, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 11067; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Vila C, Hornillos V, Giannerini M, Fananas-Mastral M, Feringa BL, Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 13078; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Wu X-F, Sundararaju B, Neumann H, Dixneuf PH, Beller M, Chem. Eur. J 2011, 17, 106; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Shen X, Hyde AM, Buchwald SL, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2010, 132, 14076; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Wu X-F, Neumann H, Beller M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2010, 49, 5284; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 5412; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Takagi J, Takahashi K, Ishiyama T, Miyaura NJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 8001; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Littke AF, Dai C, Fu GC J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 4020; [Google Scholar]; i) Patel HH, Prater MB, Squire SO Jr., Sigman MS, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 5895; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j) Yuan Q, Sigman MS, Chem. Eur. J 2019, 25, 10823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].For an example of dual Pd/Ir-catalyzed activation of aryl and alkenyl triflates, not involving hybrid Pd species, see:; Shimomaki K, Nakajima T, Caner J, Toriumi N, Iwasawa N, Org. Lett 2019, 21, 4486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].For examples of oxidative oxindole synthesis, involving intermediacy of free α-carbonyl radicals, see:; a) Song R-J, Liu Y, Xie Y-X, Li J-H, Synthesis 2015, 47, 1195; [Google Scholar]; b) Jia Y-X, Kündig EP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2009, 48, 1636; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 1664; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Donald JR, Taylor RJK, Petersen WF, J. Org. Chem 2017, 82, 11288; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Hurst TE, Gorman RM, Drouhin P, Perry A, Taylor RJK, Chem. Eur. J 2014, 20, 14063; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Teichert A, Jantos K, Harms K, Studer A, Org. Lett 2004, 6, 3477; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Kong W, Casimiro M, Merino E, Nevado N, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 14480; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Matcha K, Narayan R, Antonchick AP, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2013, 52, 7985; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 8143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Jiang Y, Yu S-W, Yang Y, Liu Y-L, Xu X-Y, Org. Biomol. Chem 2018, 16, 6647; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Klein JEMN, Taylor RJK, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2011, 6821; [Google Scholar]; c) Hillgren JM, Marsden SP, J. Org. Chem 2008, 73, 6459; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Deppermann N, Thomanek H, Prenzel AHGP, Maison W, J. Org. Chem 2010, 75, 5994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].During preparation of this manuscript, Glorius and co-workers reported a Pd-catalyzed olefin difunctionalization protocol, operating via hybrid aryl Pd-radical intermediates, generated from aryl bromides:; Koy M, Bellotti P, Katzenburg F, Daniliuc CG, Glorius F, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 2375; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Liu W, Yang X, Gao Y, Li CJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 8621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Shaughnessy KH, Hamann BC, Hartwig JF, J. Org. Chem 1998, 63, 6546; [Google Scholar]; b) Lee S, Hartwig JF, J. Org. Chem 2001, 66, 3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jutand A, Hii KK, Thornton-Pett M, Brown JM, Organo-metallics 1999, 18, 5367. [Google Scholar]

- [18].For reviews on the synthesis of oxindoles, see:; a) Brandão P, Burke AJ, Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 4927; [Google Scholar]; b) Cao Z-Y, Wang Y-H, Zeng X-P, Zhou J, Tetrahedron Lett 2014, 55, 2571; [Google Scholar]; c) Dalpozzo R, Bartol G, Bencivenni G, Chem. Soc. Rev 2012, 41, 7247; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Dalpozzo R, Adv. Synth. Catal 2017, 359, 1772; [Google Scholar]; e) Badillo JJ, Hanhan NV, Franz AK, Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev 2010, 13, 758; For selected examples of the synthesis of oxindoles, see: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Sun W, Chen C, Qi Y, Zhao J, Bao Y, Zhu B, Org. Biomol. Chem 2019, 17, 8358; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Li X, Han M-Y, Wang B, Wang L, Wang M, Org. Biomol. Chem 2019, 17, 6612; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h) Shukla D, Babu SA, Adv. Synth. Catal 2019, 361, 2075; [Google Scholar]; i) Yen A, Lautens M, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Martinez de Marigorta E, de Los Santos JM, de Retana A. M. Ochoa, Vicario J, Palacios F, Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2019, 15, 1065; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Speck K, Magauer T, Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2013, 9, 2048; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ghandi M, Zarezadeh N, Abbasi A, Org. Biomol. Chem 2015, 13, 8211; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Lippmann W, Chem. Abstr 1981, 95, 61988m; [Google Scholar]; e) Taylor EC, Zhou P, Jenning LD, Mao Z, Hu B, Jun J-G, Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 521; [Google Scholar]; f) Bisai V, Suneja A, Singh VK, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 10737; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 10913; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g) Dong W, Xu G, Tang W, Tetrahedron 2019, 75, 3239; [Google Scholar]; h) Miura H, Kimura Y, Terajima S, Shishido T, Eur. J. Org. Chem 2019, 2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].2-Hydroxybenzamide precursors can be readily accessed by the C–H oxidation method developed by Ackermann and co-workers:; a) Massignan L, Tan X, Meyer TH, Kuniyil R, Messinis AM, Ackermann L, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2020, 59, 3184; Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 3210; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Raghuvanshi K, Zell D, Ackermann L, Org. Lett 2017, 19, 1278; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yang F, Ranch K, Kettelhoit K, Ackermann L, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 11285; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 11467; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yang F, Ackermann L, Org. Lett 2013, 15, 718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen U-Q, Wang Z, Wu Y, Wisniewski SR, Qiao JX, Ewing WR, Eastgate MD, Yu J-Q, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 17884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. See the Supporting Information for details.

- [23].Andersen TL, Kramer S, Overgaard J, Skrydstrup T, Organo-metallics 2017, 36, 2058. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.