Introduction

The United States (US) is currently amid an opioid use disorder (OUD) epidemic. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that the ‘economic burden’ in terms of lost productivity, healthcare costs and criminal justice for the misuse of opioid prescriptions in the US is $78.5 billion a year (Florence, Lou, & Zhou, 2016). In 2016, the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) reported that 948,000 Americans used heroin in the past year, a number that has risen since 2007. This trend appears to be primarily driven by young adults 18–25 years of age (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2018). Alarmingly, deaths from drug overdose tripled from 1999–2014, totaling 47,055 deaths in 2014, of which 60.9% involved opioids (Rudd, Puja, David, & Scholl, 2016). The rise in opioid overdose deaths has evolved over three distinct phases; the first phase began with increased overdose deaths from prescribed opioids in the 1990s, the second phase started in 2010 with rapid increases in overdose deaths from heroin, and the third phase began in 2013 with significant overdose deaths from fentanyl, a synthetic opioid (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], n.d).

Due to the public health crisis of the OUD epidemic, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) developed initiatives to address the crisis. In 2016, the CDC introduced the Guidelines for Prescribing Opioids for Comprehensive Pain (CDC, 2018). The guideline provides recommendations for prescribing opioids for pain management in the primary care setting for adults 18 and older. Currently, for first-time opioid prescriptions, many states limit the number of days for an opioid prescription, ranging from three to 14 days (Bendix, 2018). Additionally, many states mandate prescribers to review their state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP) before writing the opioid prescription to evaluate if a patient is receiving opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that place a patient at high risk of overdose or if a patient is receiving opioid prescriptions from multiple providers (CDC, 2018). In April 2018, the NIH launched the Helping to End Addiction Long-term (HEAL) Initiative (NIH, 2019). The HEAL Initiative uses the NIH’s highly established infrastructure in basic sciences and clinical research to develop and to test treatment models to improve pain management and reduce opioid misuse (NIH, 2019). The goal of HEAL is to speed scientific discoveries and to offer hope to those affected by this crisis (NIH, 2019).

OUD is a chronic relapsing disease. Genetic variability dysregulated stress system response, and drug experimentation behaviors all contribute to the likelihood of an individual developing an opioid use disorder (Reed, Picetti, Butelman, & Kreek, 2015). In the United States, 80% of current heroin users report they previously used an opioid medication for nonmedical reasons (Muhuri, Gfroerer, & Davies, 2013, Jones, 2013). Often, individuals with an OUD find themselves consumed with their addiction and may be unable to maintain steady employment or take care of themselves or their family. OUD results in significant adverse effects on the physical and emotional health of the individual and their family and extensive negative effects on society (National Drug Intelligence Center, 2006). Tolerance, dependence, and addiction to opioids cause different effects on the body and brain. Tolerance is the need for a higher level of a substance to achieve the desired effect. Dependence is a state that occurs after repeated exposure to opioids and results in the development of withdrawal symptoms in the absence of the drug. Addiction is characterized by the uncontrollable need to use substances regardless of the harmful effects on the body or consequences to daily life (NIDA, 2018). This article discusses the pathophysiology, treatment options and implications for nursing practice for individuals with a OUD.

Pathophysiology of Opioid Use Disorder

Theories of OUD Development

Current research describes two main theories that demonstrate what “drives” an individual to take opioids; one being the concept that an individual is seeking the pleasure that opioids produce and the other being to avoid the unpleasant withdrawal symptoms of opioids (Koob, 2013, Piazza & Deroche-Gammonet, 2013). The first theory posits that there are three phases of the transition to an addiction: (a) recreational drug use: in which drug intake is moderate and sporadic and still among many other recreational activities of the individual, (b) intensified drug use: escalated use where drug intake increases and becomes the main recreational activity; although some decreased societal/personal functioning start appearing, their behavior is still mostly controlled, and (c) loss of control of drug use/full addiction that results in disorganization of the individual’s behavior; drug-related behaviors are now the main activity. The first phase occurs in most individuals as drugs cause the release of rewarding neurotransmitters, making them enjoyable. The second phase occurs in vulnerable individuals; those who have a sensitive dopaminergic system (reward system of the brain) and an impaired prefrontal cortex (increased impulsivity). The last phase is characterized by neuronal structural and signaling changes in the reward-related brain areas, leading to loss of control of drug taking behavior. In this phase, the presence of the drug is not only needed to function normally, but its absence causes intense suffering (Piazza & Deroche-Gamonet, 2013). The second theory states that the negative physical and/or psychological side effects of drug withrawal are felt to be so intolerant, that they will continue to use the drug despite the immense negative consequence (Koob, 2013).

Neurobiology of Opioid Use

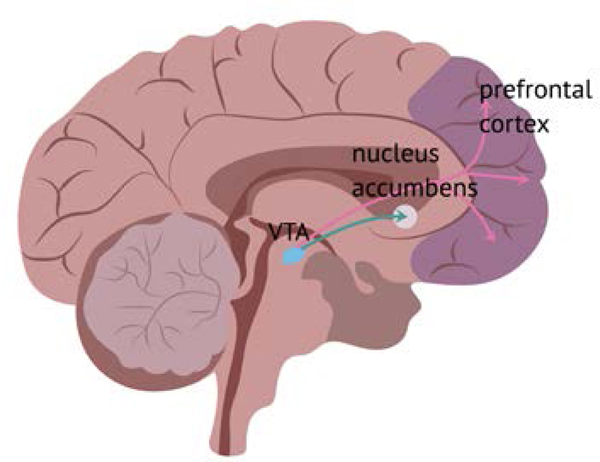

Opioid administration stimulates the mesolimbic dopaminergic reward system of the brain, as well as other systems. Opioids enter the brain and attach to opioid receptors on neurons. There are three different opioid receptors: the mu, kappa, and delta (Al-Hasani & Bruchas, 2011). When opioids attach to mu receptors in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), an increased release of dopamine (a neurotransmitter) into another area of the brain called the nucleus accumbens (NAc) occurs. The release of dopamine into the NAc causes feelings of pleasure and contentment, rewarding the individual’s drug-taking behavior (see figure 1). This may explain why an individual may take an opioid frequently in the initial stages of opioid use (Kosten & George, 2002). Additionally, other neuropeptides, such as dynorphine, are released and act on the kappa receptors, creating feelings of dysphoria. This may explain why an individual may use additional opioids in an attempt to correct the negative psychological feelings (Wilson-Poe & Moron, 2017).

Figure 1.

Effect of Opioids on the Brain

The brain releases endogenous opioids (opioids that the brain makes, i.e., endorphins) when an individual participates in activities such as exercise, eating, and sexual activity, as a reward for behaviors that promote a healthy life. Exogenous opioids (opioids not made in the brain, such as heroin) stimulate the brain to release more dopamine than is usually released with natural rewards, causing the brain to make adaptations in neuron structure and signaling. Eventually, these adaptations create a situation where ordinarily pleasurable events do not feel enjoyable without exogenous opioids present (e.g., dysphoria) (Kosten & George, 2002). Under normal circumstances, the prefrontal cortex of the brain (which mediates cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning) stops us from behaviors that may be overly risky in the pursuit of pleasure. However, the prefrontal cortex is compromised in individuals with an OUD, either as a result of drug use or an inherited trait (or both) further increasing the risk of a OUD development (Kosten & George, 2002, Koob, 2013, Piazza & Deroche-Gamonet, 2013).

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adeneal (HPA) Axis System

The hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a neuroendocrine pathway that controls the body’s response to stress. Under normal conditions, the hypothalamus gathers signals from the brain including the cortex, autonomic system, environmental inputs, and the peripheral endocrine feedback to then release corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH). CRH acts on the anterior pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which then directs the adrenal glands to secrete cortisol (see figure 2) (Chrousos, 1995, Milivojevic & Sinha, 2018). The body reacts to cortisol in several ways to cope with a stressor: heart rate, blood pressure, and blood glucose increase; bronchioles dilate, blood from the gastrointestinal tract and kidneys divert to the brain, and the immune system is suppressed (Lee, Kim, & Choi, 2015). When an opioid is administered, the HPA axis dampens, and when opioid withdrawal occurs, the HPA axis is stimulated. Over time, the HPA axis becomes hyper-responsive after a continuous pattern of opioid intoxication/withdrawal. Studies show that stress can trigger cravings (Kreek & Koob, 1998, Milivojevic & Sinha, 2018). Six months after the individual with a OUD has stopped using opioids, the HPA axis hyper-responsivity persists putting the individual at risk of relapse (Kreek, Ragunath, Hamer, Schneider, Hartman, 1984).

Figure 2.

Effects of Opioids on the Stress Response

In summary, the combined effects of the HPA axis disruption, the development of tolerance, dependence, and addiction, and the adaptations that the brain makes to cope with a massive influx of exogenous opioids can explain how challenging it is for an individual with an OUD to remain drug-free. Education of the neurobiology of OUD helps nurses to understand the behaviors of the individual with an OUD better and approach them with empathy.

Nursing Interventions

Opioid Use Assessment

If you suspect an individual is abusing a substance, an empathetic approach is incredibly useful for establishing a connection and rapport. Having a genuine interest in the life of an individual with an OUD while remaining objective and kind will help them feel valued and respected. It is of utmost importance to let them know that they are safe speaking with you and that they can trust you to have their best interests in mind (Rollnick, Miller, &Butler, 2008).

Nurses also need to recognize the signs of opioid use. The signs and symptoms of acute opioid use include slurred speech, sedated appearance, impaired concentration, analgesia, cough suppression, pinpoint pupils, and “track marks” (pattern of healed and/or acute puncture wounds from an intravenous needle, usually found along a vein on the non-dominant arm). Chronic opioid use can lead to constipation, various infections of the skin, lining of the heart, and bones, HIV, hepatitis B, and C, and an increased risk for pneumonia and tuberculosis. These individuals are also at risk for hyperalgesia, accidents/trauma, and overdose. The signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal include runny nose, tearing, yawning, sweating, tremors, vomiting, piloerection (“goosebumps”), pupillary dilation, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, nausea and vomiting, bone/muscle pain, dysphoria, “skin crawling” and a craving for opioids (SAMSHA, 2018).

Screening Tools

There are several screening tools available to assess for opioid use in clinical practice. These tools include the Kreek-McHugh-Schluger-Kellog (KMSK) questionnaire, the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10), and the DSM-5 Opioid Use Disorder Checklist. The KMSK questionnaire takes five minutes to complete and assesses the maximal use of opioids, cocaine, alcohol, and tobacco in an individual’s lifetime and within the past 30 days, and also evaluates the mode of use (Butelman, Chen, Fry, Kimani, Levran, Ott, Correa, & Kreek, 2018). The DAST-10 is a 10-item, self-report scale that screens for the abuse of drugs in the past 12 months. A total score ranging from 0 to 10, corresponds with suggested treatment actions and provides a quick guide of possible drug abuse problems (Evran, Can, Yilmaz, Ovali, Cetingok, Karabulut, and Mutlu, 2013)). DSM-5 Opioid Use Disorder Checklist is an 11-item questionnaire that is used to diagnose an opioid use disorder. A minimum of two positive responses on the questionnaire equates with a clinically significant pattern of opiate abuse. At the completion of the checklist, a severity rating score of mild, moderate or severe is achieved (Hason, O’Brien, Auriacombe, Borges, Bucholz, Budney, Compton, Crowley, Ling, Petry, Schuckit, Grant, 2013). Links for each of the screening tools is listed at the end of this article.

Behavioral Interventions

Several behavioral and counseling techniques have demonstrated efficacy in reducing substance use and when combined with pharmacotherapy, provide enormous positive outcomes. These include motivational interviewing (MI), rewards management and cognitive behavioral therapy (McHugh, K., Hearon, B., Otto, M, 2010). Below is a brief description of each intervention.

| Therapy Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Motivational Interviewing | Motivational interviewing is a counseling technique that helps the individual with an OUD work through ambivalence for change and develop motivation. |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | Technique that helps the individual with an OUD identify triggers for relapse by focusing on the patient present situation. Relaxation exercises and social techniques are taught. |

| Contingency Management | Contingency management uses tangible rewards (cash prizes, vouchers) to foster positive behaviors. The rewards are used to modify the individual with an OUD’s behaviors. |

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a patient-centered, directive method of counseling that helps the patient enhance their intrinsic motivations to change by exploring and resolving their ambivalence to change. It is an instrumental technique that provides a guideline to assess an individuals’ readiness for change and offers suggestions for eliciting and encouraging positive health choices. In the healthcare setting, the MI approach is used in a variety of areas that require behavior change, such as weight loss and addiction (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003). Change is a complicated and sometimes over-lapping experience. It involves thinking about change, taking action, stumbling backward, and then starting over again (Smith, 2014). MI is used to elicit and identify the current stage of change that an individual with a OUD is experiencing. MI can guide the nurse’s interventions, respond with empathy, and offer helpful advice and recommendations (Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2008). The basic principle of MI are to 1) resist the righting reflex- avoid the desire to tell the individual with a OUD that they should stop using opioids; instead elicit a conversation with them so that they verbalize reasons to stop using, 2) understand their motivations- be interested in the individual with a OUD’s concerns and motivations as it will be their reasons that will trigger them to want to stop using, 3) listen to them- the ability for the individual with a OUD to stop using opioids starts with them deciding to do so, empathetic interest from the nurse naturally leads to good listening that helps them identify reasons to stop using, and 4) empower the individual with a OUD- help them identify a plan to stop using (Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2008). MI is a method that nurses can learn, but proper training and practice are essential to acquire the necessary skills to deliver MI accurately (Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola, 2003). For this paper, a concise, adapted form of MI is outlined (table 1) to guide the nurse with applying MI for the individual with an OUD. The following table provides a way to quickly identify which stage of change the individual with a OUD is currently in (by using the “objective behavior”) column, get an idea of what they may be thinking (by using the “internal processes” column), and provides clear examples of responses/actions nurses can make to illicit change behavior (found in the “actions/examples of questions to make” column)

Table 1.

Using Motivational Interviewing to Support Patients with OUD

| Stage | Description of change | Objective Behavior | Internal Processes | Motivational Interviewing Goals | Examples of Questions/Actions to Take |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1)Precontemplation | Not ready to stop using illicit opioids. | The individual with a OUD does not intend to stop using illicit opioids. They do not acknowledge they have an addiction and make excuses to continue to use illicit opioids. | The individual with a OUD may feel that the necessary changes will take too much work or bring discomfort (i.e., withdrawal). Hopelessness may be present due to failed past attempts, or a general lack of self-worth may be present. | -Assist the individual with a OUD in identifying the negative consequences of using illicit opioids, and how their life may benefit if they stopped using. -Help them explore reasons to stop using illicit opioids. -Assist them in identifying things they like about themselves and are proud of to build confidence and self-worth. -Educate on the addiction disease process, provide them with handout materials and refer them to reputable education websites. |

- Ask: “Can I ask you, how has your life changed since you started using heroin/opioids?” -Ask: “Do you ever feel it gets in the way of your relationships/work/school/taking care of yourself or family?” - Ask: “What do you think your life would be like if you weren’t using illicit opioids?”, “What do you think would change?” - Ask: “Tell me about an experience in your life where you felt proud of an accomplishment you made” - Ask: “Can you tell me five things about yourself that you are proud of”. - Refer them to resources that explain the negative consequences of using illicit opioids (see referenes). |

| 2) Contemplation | Thinking about change, getting ready to stop using illict opioids. | The individual with a OUD becomes aware of the negative consequences of using illicit opioids. However, they may still be ambivalent about stopping. They are weighing the pros and cons of stopping illicit opioids. |

A sense of urgency or motivation to change is crucial in this stage for further change development. | -Assist in further identifying reasons to quit using illicit opioids. -Help them to explore possible barriers to quitting and solutions. -Help the individual with a OUD find resources to learn about “success stories” or identify a role model that has successfully quit illicit opioids. |

-Ask, “What are the three best reasons to quit using illicit opioids?” -Ask, “Why would you want to quit illicit opioids?”, “How would you do it, if you decided to?” - Ask, “Can you think of anything/anyone that would help you quit using illicit opioids? “Anyone/anything that would prevent you from quitting?” -“Ask: Is there anyone in your life that has successfully quit a drug before?”. If they are not able to identify anyone, refer them to the references section of this paper for a link to a webpage on “success stories”. |

| 3) Preparation | Ready to stop using illicit opioids. | An individual with a OUD has committed to stop using illicit opioids. They make statements such as, “I can’t do this anymore.” | The number one concern of individuals with an OUD will have at this stage is, “Will I fail?” | -Assist them in developing a plan on how to stop using; refer them to treatment centers and support groups. -Help them to identify a quit date. Explain that relapses are expected, but that it is essential not to give up after a relapse. |

-Ask them, “Can you think of a date to quit using opioids?”. - Refer to the reference section for links to “treatment centers”. -Tell the patient, “relapses are expected, the important thing is to not give up”. |

| 4) Action | Stopping the use of illicit opioids. | Individuals with a OUD are implementing the plan they made to stop using illicit opioids and are successful. | Individuals with a OUD may be experiencing a fear of failure, resistance to change, and lack of social support putting them at an increased risk of relapse. -They may develop unrealistic expectations about their progress (i.e., after two weeks of not using illicit opioids, they become upset that family ties are unrepaired). |

-Encourage positive behavioral changes by celebrating small successes and explain that recovery can take a while to achieve. - Help them to assist in identifying and establishing support systems with individuals who do not use illicit opioids. |

- Express encouragement by congratulating them, “I can tell that you have not been using illicit opioids (comment on a change in their appearance or attitude), that’s great!, How do you feel?” - Ask: “Have you made any connections with other people who are in recovery?”, if they answer “No” ask, “Would you like some help with finding support?” - If they are feeling negative about a perceived lack of progress in relationships they neglected while using explain that change takes time and people process emotions at different rates. |

| 5) Maintenance | Not using illicit opioids for at least six months. | They are committed to not using illicit opioids and have been successful in coping with temptations and triggers. | External factors such as stressful life events or an encounter with a friend they previously used illicit opioids may precipitate a relapse. | -Encourage the former individual with a OUD to establish new friends, avoid triggers (people, places, and things), and develop positive, healthy coping mechanisms (exercise, volunteering, psychotherapy). - Continue to celebrate their successes. |

-“I am happy to hear that you decided to (join a support group/receive talk therapy/start exercising, ect.), how do you feel?” -Continue to express encouragement by congratulating them, “You have been doing so great, Congratulations on (any achievement they made such as not using/getting stable housing or job/school/reestablishment of a relationship)!, Way to go!, you must be so proud of yourself!”, |

| 6) Termination | Not using illicit opioids for 2 years. | They have a new image which may be observable in their behavior and attitude. | They have achieved a feeling of “I’ve been there, and I am not going back.” | -Congratulate them on their success and continue to encourage positive health behaviors. | -“You have come a long way and have made an incredible amount of positive changes to your life, Congratulations!”, “You must be proud of yourself!” |

Medication Treatment Options

Individuals with a OUD need access to a variety of treatment modalities to remain free from illicit opioid use successfully. Medication, mental health services (if required), medical care, addiction counseling, and recovery support services work together to provide a holistic approach (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2018). Unfortunately, MAT is greatly underused and there are still providers who encourage an abstinence-only approach. For instance, according to SAMHSA’s Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) 2002–2010, the proportion of heroin admissions with treatment plans that included receiving medication-assisted opioid therapy fell from 35% in 2002 to 28% in 2010. The slow adoption of these evidence-based treatment options for opioid dependence is partly due to misconceptions about substituting one drug for another (SAMHSA, 2019). The goal of medication maintenance therapy for opioid addiction is to help the individual with a OUD avoid withdrawal symptoms and minimize cravings, allowing them to attend psychological rehabilitation, reconnect with family and friends, and return to a productive lifestyle. Medications prescribed for opioid addiction fall into three classes: 1) full mu-opioid agonist, 2) partial mu-opioid agonist and 3) opioid antagonist. Full opioid agonist medications, like methadone, occupy the opioid receptor in the same way heroin does, however, methadone’s duration of action is longer (half-life is approximately 24 hours in opioid-tolerant individuals, (Grissinger, M, 2011)) than heroin. The longer duration of action results in a normalization of the HPA axis, minimizes opioid withdrawal symptoms and cravings, inhibits the effect of additional illicit opioid, and reduces the risks associated with compulsive opioid use (contracting HIV, hepatitis C, and criminal activity) (Li, Shorter, Stine, & Kosten, 2015, SAMSHA, 2018). Mu opioid partial agonists-antagonists such as buprenorphine-naloxone occupy the mu-opioid receptor partially, providing the advantages that methadone offers (as listed above) but with a “lesser maximal” effect (less analgesia, respiratory depression, euphoria, ect.) due to its partial effect on the mu opioid receptor. Opioid antagonists, such as naltrexone attach to the opioid receptor but do not cause opioid effects. Essentially, naltrexone blocks the effect of opioids, thereby, preventing the opioid-addicted individual from experiencing the “high” of opioid administration. (Li, Shorter, Stine, & Kosten, 2015, SAMSHA, 2018).

| Medication | Mechanism of Action | Adverse Effects | Implications for Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methadone | Full mu-opioid Agonist | - Constipation, nausea, drowsiness, sweating, sexual dysfunction, prolonged QT interval, weight gain,edema, amenorrhea, and overdose. | - The patient needs to attend a licensed treatment center daily (initially), which can interfere with lifestyle flexibility. -Good option for those with moderate to severe OUD or who failed buprenorphine-naloxone treatment. - Higher risk of overdose compared to buprenorphine-naloxone. |

| Buprenorphine-Naloxone | Partial mu-opioid agonist/antagonist | - Constipation, vomiting, insomnia, sweating, blurred vision, oral hypoesthesia (oral numbness), glossodynia (tongue pain), palpatations. | - The patient can receive a prescription from a primary care provider (MD, NP, PA). The providers must complete and maintain certification to prescribe this medication. -Available in a daily oral sublingual and a long-term implant formulation; providing lifestyle flexibility. -Good option for those with moderate to severe OUD, are motivated to quit and can tolerate a reduced opioid effect. - Overall lower risk of overdose than methadone, except if taken with benzodiazepines or alcohol. |

| Naltrexone | Opioid Antagonist | -Insomnia, hepatic dysfunction, and nasopharyngitis. | - The patient can receive a prescription from a primary care provider (MD, NP, PA). -Available in a daily oral or monthly injection; providing lifestyle flexibility. -Naltrexone may interfere with pain medications given for acute illnesses or trauma. -Good option for those with mild OUD, a high level of motivation to quit all forms of opioids. |

Summary

Several studies have shown that those with substance use disorders are stigmatized more than other health conditions and that individuals with a OUD are often treated as though they have a moral and criminal issue (Livingston, Milne, Fang, Amari, 2011) rather than a chronic disease. Education on the pathophysiology of opioid addiction, treatment options, and empathic listening is paramount to break through this cycle of shame and blame. Nurses can play an essential role in advocating for implementing opioid use screening tools in practice, apply motivational interviewing to elicit the individual with a OUD’s reasons to stop using, and assist them in receiving appropriate treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Mary Jeanne Kreek, Eduardo Butelman, PhD, and Brian Reed, PhD. This work is supported in part by grant # UL1TR001866 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program.

Footnotes

Referrals for Individuals with a OUD

Screening Tools:

KMSK scale: http://lab.rockefeller.edu/kreek/assets/file/KMSKquestionnaire.pdf

DAST scale: https://cde.drugabuse.gov/sites/nida_cde/files/DrugAbuseScreeningTest_2014Mar24.pdf

DSM 5 opioid use disorders checklist: https://www.aoaam.org/resources/Documents/Clinical%20Tools/DSM-V%20Criteria%20for%20opioid%20use%20disorder%20.pdf

Treatment locators:

-Faces and Voices of Recovery Guide to Mutual Aid Resources, list of recovery support groups throughout the U.S: http://facesandvoicesofrecovery.org/resouces/mutual-aid-resources

-Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, directory of inpatient treatment providers: http://findtreatment.samhsa.gov

www.samsha.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/physician-program-date/treatment-physician-locator

-VA Substance Use Disorder Program Locator, provides treatment locator for veterans with substance use disorders: www.va.gov/directory/guide/SUD.asp -

“Success Stories” and Online Support Groups:

-A.T. Watchdog: a methadone maintenance support group- www.facebook.com.groups/1599996730222196

- Heroin Anonymous: www.facebook.com/HeroinAnonymous

-Medication-Assisted Miracles: www.facebook.com/groups/MATMiracles

Online Tutorials:

General information on drug addiction: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/understanding-drug-use-addiction

Information on the pathophysiology of opioid addiction: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NDVV_M__CSI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9gTgSvyE_Hg

Research initiatives that address the opioid crisis: https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/heal-initiative

Contributor Information

Kate Garland Brown, The Laboratory of the Biology of Addictive Diseases, The Rockefeller University, 1230 York Avenue, Box 171, New York, NY 10065.

Bernadette Capili, The Rockefeller University, 1230 York Avenue, Hospital, Room 106, New York, NY 10065.

References

- Al-Hasani R, Bruchas M (2011) Molecular mechanisms of opioid receptor-dependent signaling and behavior. Anesthesiology, 115(6), 1363–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendix J (2018). Opioid policy fallout. Medical Economics, 10, 96 Retrieved June 18, 2019 https://www.medicaleconomics.com/business/opioid-policy-fallout [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Volkow N (2019) Management of opioid use disorder in the USA:present status and future directions. The Lancet,393(10182), 1760–1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke BL, Arkowitz H, & Menchola M (2003). The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting on Clinical Psychology, 71, 843–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butelman E, Chen C, Fry R, Kimani R, Levran O, Ott J, Correa R, Kreek M (2018) Re-evaluation of the KMSK scales, rapid dimensional measures of self-exposure to specific drugs: gender specific features. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 190, 179–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control (n.d). Understanding the epidemic. Retrieved March 14, 2019, from https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018. Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes — United States. Surveillance Special Report 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Published August 31, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chrousos GP, (1995). The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and immune-mediated inflammation. New England Journal of Medicine, 332(20), 1351–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evran C, Can Y, Yilmaz A, Ovali E, Cetingok S, Vahap K, Karabulut V, Mutlu E (2013). Psychometric properties of the drug abuse screening test (DAST-10) in heroin dependent adults and adolescents with drug use disorder. The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 26, 351–359 [Google Scholar]

- Florence C, Lou F, & Zhou C (2016). The economic burden of prescription opioid overdose, abuse and dependence in the United States, 2013. Med Care, 54(10), 901–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grissinger M (2011). Keeping patients safe from methadone overdoses. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 36(8) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D, O’Brien C, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, Compton W, Crowley T, Ling W, Petry N, Schuckit M, Grant B (2013) DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(8), 834–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herron AJ, & Brennan TK (2015). The Asam Essentials of Addiction Medicine (2nd edition ed.). [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM. (2013). Heroin use and heroin use risk behaviors among nonmedical users of prescription opioid pain relievers – United States, 2002–2004 and 2008–2010. Drug Alcohol Dependence,132(1–2):95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellogg SH, McHugh PF, Bell K, Schluger JH, Schluger RP, LaForge KS, Kreek MJ (2003). The Kreek-McHugh-Schluger-Kellogg scale: a new, rapid, method for quantifying substance abuse and its possible applications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 69(2), 137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF. (2013) Negative reinforcement in drug addiction: the darkness within. Current Opinions in Neurobiology, 23(4): 559–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, & George TP (2002). The neurobiology of opioid dependence: implications for treatment. Science and Practice Perspectives, 13–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Koob GF (1998). Drug dependence: stress and dysregulation of brain reward pathways. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 51, 23–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Ragunath S, Levy S, Hamer D, Schneifer B, Hartman B (1984) ACTH, cortisol and B-endorphine response to metyrapone testing during chronic methadone maintenance treatment in humans. Neuropeptides, 5, 277–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Kim E, Choi M (2015) Technical and clinical aspects of cortisol as a biochemical marker of chronic stress. BMB Reports, 48(4), 209–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Shorter D, Stine S, & Kosten TR (2015). Pharmacologic Intervention for Opioid Dependence In The ASAM Principles of Addiction Medicine (2nd ed (pp. 294–299). China: Wolters Kluwer. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh KR, Hearon BA, Otto MW (2010) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am,33(3): 511–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milivojevic V, Sinha R (2018) Central and peripheral biomarkers of stress response for addiction risk and relapse vulnerability. Trends in Molecular Biology, 24(2), 173–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhuri PK, Gfroerer JC, & Davies C (2013). Associations of nonmedical pain reliever use and initiation of heroin in the United States. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration CBHSQ Data Review. [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC). (2006). The impact of drugs on society. National Drug Threat Assessment 2006. Retrieved on June 19, 2019 from: https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs11/18862/impact.htm [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018). What is the scope of heroin use in the United States? Retrieved June 2018, from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/heroin/scope-heroin-use-in-united-states

- National Institute on Drug Abuse (2018). The science of drug use and addiction: the basics. Retrieved March 20, 2019, from http://www.drugabuse.gov.publications/media-guide/science-drug-use-addiction-basics

- National Institutes of Health (2019). NIH helping to end addiction long-term. Retrieved June 18, 2019, from https://www.nih.gov/research-training/medical-research-initiatives/heal-initiative.

- Petry N, Martin B (2002). Low-cost contingency management for treating cocaine and opioid-abusing methadone patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology,70(2), 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza PV, Deroche-Gamont V (2013) A multistep general theory of transition to opioid use disorder. Psychopharmacology, 229(3): 387–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed B, Picetti R, Butelman ER, & Kreek M (2008). Chapter 19: Neurobiology of Opiates and Opioids In The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Substance Abuse Treatment (4th ed.) pp. 277–294. Arlington, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, & Butler CC (2008). Chapter 1: Motivational Interviewing Principals and Evidence In Motivational Interviewing in Health Care (pp. 3–10). New York, NY: : The Guilford Press. National Institute on Drug Abuse. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd RA, Seth P, Felicita D, & Scholl L (2016). Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-Unites States 2010–2015. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/mm655051e1.htm [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smith EJ (2014). Chapter 10: motivational interviewing and the stages of change theory In Felts DC, Theories of Counseling and Psychotherapy: An Integrative Approach (2nd ed.), p. 319–344. London, UK: Sage [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). TIP 63: medications for opioid use disorder for healthcare and addiction professionals, policymakers, patients, and families. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. [Google Scholar]