The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has disrupted routines and halted training, causing a significant reduction in the opportunity to learn endoscopy. The disruption highlights the deficiencies of the current model used to learn endoscopy and points toward the much-needed reform.

“See one, do one, teach one,” the traditional learning model for surgery, which was credited to Halsted in the early 1900s, remains the predominant method to learn endoscopy today (1). Using this model, the apprentice learns primarily through direct patient encounters. By contrast, our immediate working colleagues, the anesthesiologists, and surgeons have adopted simulation-based learning models for their trainees (2). Simulation-based learning, when compared with traditional education, has shown a substantial effect on skills and a moderate effect on patient outcomes (3). Despite advances in simulation-based learning, studies evaluating its impact on the practicing clinicians are lacking. The paucity of evidence coupled with a historic reliance on the apprentice-based system of training has resulted in a severely limited opportunity for practicing gastroenterologists to train, maintain, or retrain endoscopy techniques (4).

In this article, we aim to illustrate the use of simulation-based mastery learning (SBML) (5) in assisting practicing gastroenterologists to acquire and enhance critical skills required for optimizing patient safety and outcomes. We will share our experience of training practicing gastroenterologists with the clipping over the scope technique (Ovesco, Tubingen, Germany) using SBML. By providing distinct real-world examples that demonstrate significant and rapid acquisition of new skills, we hope to highlight the potential role of SBML to modernize the current endoscopy training, particularly in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

SIMULATION-BASED MASTERY LEARNING

Mastery learning (ML) is a well-developed and robust form of competency-based education that ensures all the graduates learn uniformly. In ML, learners acquire the pertinent knowledge and skills to meet a preset minimum passing standards before advancing to the next phase of learning (6). A critical component of ML is its emphasis on deliberate practice with feedback that is tailored to the learner's pace. ML emphasizes mainly on achieving competency rather than meeting the scheduled timeline. Importantly, simulator use is an essential component of ML because learners can practice while receiving feedback and demonstrate competency before advancing to the next task and ultimately meeting the course objectives (6).

STEPS TO CREATE AN SBML COURSE

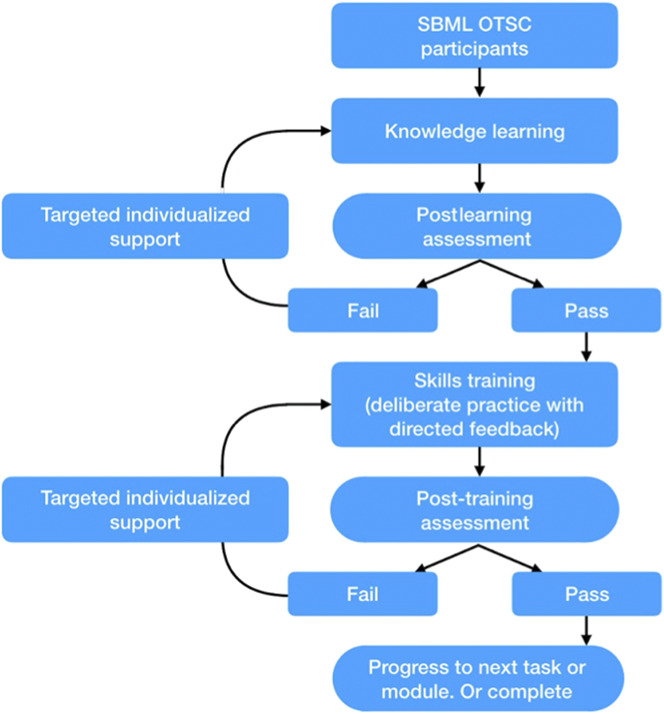

We incorporated the 7 mandatory steps detailed by McGahie et al. (7) and designed an SBML course to train and retrain gastroenterologists on the use of over-the-scope clip to treat gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation (Figures 1 and 2) (8). We used an online learning management system (Canvas, Instructure, Salt Lake City, UT). In the beginning, we conducted a pre-training knowledge assessment. We then provided the relevant knowledge base to gain a comprehensive understanding of the clip application. The faculty (R.S., R.A., and T.K.) with significant experience in the use of over-the-scope clip and endoscopy education selected the pertinent published literature and used the digestive disease week (DDW) endoscopy learning videos (9–16). Learners had 2 to 4 weeks to complete the knowledge base before taking a final summative knowledge assessment. We then conducted in-person training where learners deliberately practiced with feedback deploying the over-the-scope clip on silicone models under expert coaching. We measured the change in knowledge and surveyed their satisfaction at the end of the course. We used descriptive and Student t test statistics. We received an IRB waiver.

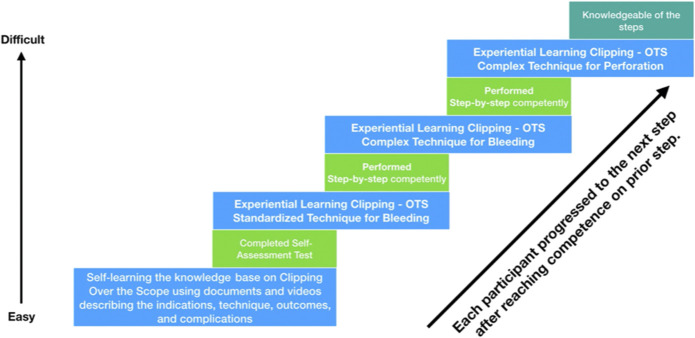

Figure 1.

Flowchart of our simulation-based mastery learning exercise to acquire knowledge and skills on the over-the-scope clip application.

Figure 2.

Each learner progressed to the next level only after they have achieved mastery in the initial task. The tasks were sequenced based on increasing difficulty. After gaining mastery in the standardized technique of clipping over-the-scope, learners learned the use of the over-the-scope clipping accessories, which can be complex to operate. Learners must be competent in all the methods to complete the course.

We conducted the SBML course at the Singapore General Hospital involving 24 gastroenterologists (mean age 40 ± 10 years, 83% men) and at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, engaging 12 gastroenterologists (mean age 44 ± 8.4 years; men 58%) and 12 fellows (mean age 33 ± 2.2 years; men 58%).

Most (53%) gastroenterologists and all fellows were novices in using the over-the-scope clip; 16 (44%) gastroenterologists have deployed less than 5 clips, whereas one (3%) had extensive experience. For this article, we included the results observed among gastroenterologists. Some data have been presented in part by our team (17).

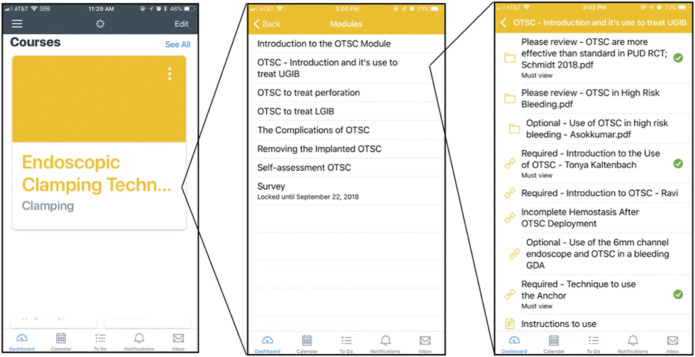

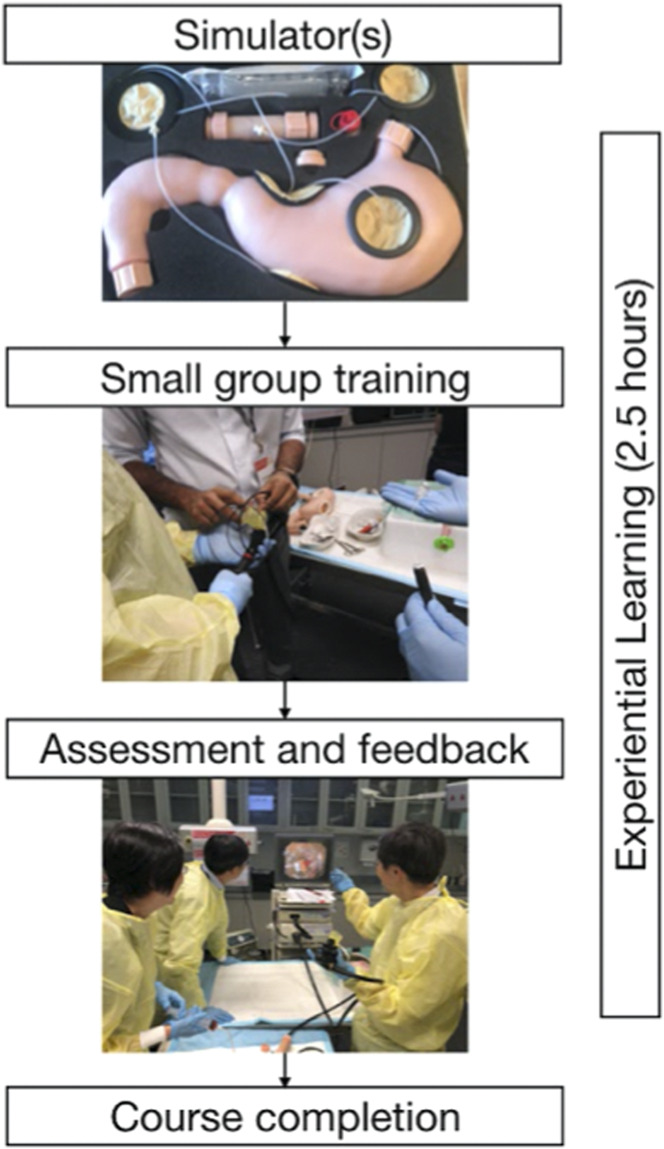

The participants spent an average of 1.72 ± 0.4 to complete the online module (Figure 3). All attendings completed the self-learning module. They spent 2.5–3 hours learning clip application first on silicone bleeding stomach models (Ovesco, Tubingen, Germany) and subsequently on porcine explants. At the University of North Carolina, only silicone models were used. All participants alternated the role of assistant and endoscopist and deliberately practiced with feedback until they demonstrated competence (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

The structure of the cloud-based knowledge contents that the learners' self-study before attending the experiential learning. The course includes a pretest and post-test, and learners are requested to pass the minimum passing standards.

Figure 4.

The bleeding simulator used in our course. Arterial bleeding is simulated during experiential learning. Learners typically deploy and assist multiple times to achieve competency in performing and helping the deployment of the over-the-scope clip.

For the Singapore cohort, 6 faculty with extensive experience in over-the-scope clip conducted the training in small 4-person groups. For the US cohort, one faculty with extensive experience and 3 assistants held the small 4-person group experiential course over 2 sessions. Trainees were briefed on the objective and schedule of the course, the assessment checklist, and the minimum passing standards (MPSs) required to demonstrate mastery at the end of the course. We defined MPS as the ability to perform all the steps of over-the-scope clip deployment without assistance consistently. All the participants, irrespective of their previous experience, completed the hands-on session and met the MPS after 6 to 8 attempts (see Figure 1, Supplementary Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/AJG/B593). Most (92%) participants agreed that the SBML course was well-paced and covered all the essential content on the topic. They rated the course highly (9.5 ± 0.8 out of 10), and all strongly agreed that they would attend similar courses in the future for other endoscopic procedures.

After the course, we tracked the number of clips deployed in clinical practice. In the Singapore cohort, at 4 months, we observed a 50% increase in the adoption rate among the new users (P < 0.006). We found that 15 over-the-scope clips were placed for duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer, gastric fistula, anal transition zone bleeding, and gastric anastomotic dehiscence. Seven novice gastroenterologists deployed the majority (67%), and the remainder were placed by those with minimal experience (<5 clips) before the course. Likewise, in the US group, at 1-month, we witnessed a 75% increase in clip application by novice gastroenterologists during GI bleeding call. They placed 11 over-the-scope clips for a variety of gastrointestinal conditions successfully. Three of the 4 fellows who were on-call together deployed 5 clips. Notably, one of them successfully treated a patient with recurrent bleeding after surgery of a perforated duodenal ulcer. None reported complications with the over-the-scope clip application.

The training experience and the results from the 2 different countries show that SBML resulted in quick dissemination of technical knowledge and skill, enabling practicing gastroenterologists to acquire and adopt a new procedure in practice. Notably, the overall time spent on training the latest knowledge and expertise was approximately 5 hours and was perceived to be adequate by most of the participants.

SUMMARY

Our experiences illustrate the significant potential of SBML to train and retrain the practicing gastroenterologists and hepatologists (and trainees) and enable them to acquire new skills successfully. Notably, these skills learned out of a non-apprentice-based training model were safely employed in patient care. This observation is novel. The need to develop the knowledge base, simulators, and the framework for conducting SBML is urgent. Building these will allow us to upgrade to a more efficient and effective training system in endoscopy. As we navigate situations filled with uncertainty and unpredictability due to COVID-19, SBML may pave the way to a new era of training, allowing practitioners and trainees to learn the required knowledge at their own time and practice the skills deliberately with feedback until competence is achieved.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Roy Soetikno, MD, MS, FACG, is accepting full responsibility for the conduct of the study.

Specific author contributions: R.S.: study concept and design, manuscript draft, study supervision, and data analysis; R.A.: study concept and design and manuscript draft; S.M.: study concept and design; T.K: study concept and design, manuscript draft, and study supervision.

Financial support: Funding for the Mastery Learning program used in this report was supported, in part, by a gift from the Academy of Endoscopy, a grant from the Asian Endoscopy Research Forum, and ACG Edgar Achkar Visiting Professor program 2021.

Potential competing interests: R.S. is a consultant for Olympus and Fuji. T.K. is a consultant for Olympus, Medtronic,and Aries Pharmaceuticals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We want to acknowledge Carmel Malvar, BSc, and Tiffany Nguyen-Vu, BSc, from the San Francisco VA for their significant assistance in the data collection, manuscript draft, and technical support. We also would like to acknowledge the assistance of Yung Ka Chin, MBChB, MRCP, and Ennaliza Salazar, MBChB, MRCP, from Singapore General Hospital for the vital contribution in conducting the training course in Singapore.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL accompanies this paper at http://links.lww.com/AJG/B593

REFERENCES

- 1.Halsted W. The Training of the Surgeon. Vol 15 Johns Hopkins Hospital; 1904. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waschke KA, Anderson J, Valori RM, et al. ASGE principles of endoscopic training. Gastrointest Endosc 2019;90:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Cohen ER, et al. Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Acad Med 2011;86:706–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.PA-19-065: Medical Simulators for Practicing Patient care providers Skill acquisition, outcomes assessment and technology development (R01 clinical trial not allowed). (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PA-19-065.html). Accessed April 22, 2020.

- 5.Nguyen-Vu T, Malvar C, Chin YK, et al. Simulator-based mastery learning (SBML) for rapid acquisition of upper endoscopy knowledge and skills–initial observation. VideoGIE 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.vgie.2020.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGaghie WC. Mastery learning: It is time for medical education to join the 21st century. Acad Med 2015;90:1438–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGaghie WC. Comprehensive Healthcare Simulation: Mastery Learning in Health Professions Education. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGaghie WC, Siddall VJ, Mazmanian PE, et al. ; American College of Chest Physicians Health and Science Policy Committee. Lessons for continuing medical education from simulation research in undergraduate and graduate medical education: Effectiveness of continuing medical education: American college of chest physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest 2009;135:62S–68S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asokkumar R, Soetikno R, Sanchez-Yague A, et al. Use of over-the-scope-clip (OTSC) improves outcomes of high-risk adverse outcome (HR-AO) non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB). Endosc Int Open 2018;6:E789–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Asokkumar R, Kaltenbach T, Soetikno R. Use of over-the-scope clip to treat bleeding duodenal ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:459–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmidt A, Gölder S, Goetz M, et al. Over-the-Scope clips are more effective than Standard endoscopic therapy for Patients with recurrent bleeding of peptic ulcers. Gastroenterology 2018;155:674–86.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobara H, Mori H, Nishiyama N, et al. Over-the-scope clip system: A review of 1517 cases over 9 years. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;34:22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wedi E, Gonzalez S, Menke D, et al. One hundred and one over-the-scope-clip applications for severe gastrointestinal bleeding, leaks and fistulas. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:1844–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wedi E, Fischer A, Hochberger J, et al. Multicenter evaluation of first-line endoscopic treatment with the OTSC in acute non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding and comparison with the rockall cohort: The FLETRock study. Surg Endosc 2018;32:307–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asokkumar R, Soetikno R. Misplaced “bear claw” in a bleeding gastric ulcer: What next?. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;84:366–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salazar E, Asokkumar R, Tan DMY, et al. 1160 treatment of iatrogenic duodenal Perforation using over the Scope clip. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:AB159. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soetikno R, Asokkumar R, Chin YK, et al. Rapid and safe crossing of the chasm: Application of a flipped learning framework for the clipping over the scope technique. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2020;30:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]