To the Editor:

Dermatologic health care disparities disproportionately affect patients with skin of color (SoC) (defined as Fitzpatrick skin phototypes IV-VI), resulting in delayed treatment courses and increased morbidity and mortality.1–3 Although many factors contribute to health care disparities, a lack of familiarity with disease presentation in patients with SoC is a physician-dependent factor that influences care quality.1,2,4,5 The aim of this study was to assess medical students’ diagnostic accuracy using clinical images of SoC and light skin (Fitzpatrick phototypes I-III).

Medical students at Tulane University School of Medicine and the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine were offered participation in a 10-item multiple choice quiz consisting of photos with a limited vignette without mention of race. Participants were randomly assigned to receive quiz A or B. Each quiz tested the same 10 conditions in the same order. Quiz A used photos from patients with Fitzpatrick I-III skin phototypes for odd-numbered questions and Fitzpatrick IV-VI skin phototypes for even-numbered questions; quiz B was the reverse.

A total of 227 students enrolled in the study (N = 227/1420; 16% response rate), 177 completed the study (n = 177/227, 78% completion rate). Preclinical medical students ( years 1 and 2) scored an average of 47.3% on both quizzes compared with clinical medical students ( years 3 and 4), who scored an average of 62.0% (t(175) = −5.51, P < .00001). Both medical schools include didactic lectures in dermatology during the preclinical years and offer elective clinical rotations.

Across all Fitzpatrick skin phototypes, the conditions most frequently identified correctly were herpes zoster (83.1%), psoriasis (81.9%), and atopic dermatitis (80.2%). The conditions least frequently identified correctly were verruca vulgaris (26.6%), contact dermatitis (30.5%), and squamous cell carcinoma (30.5%).

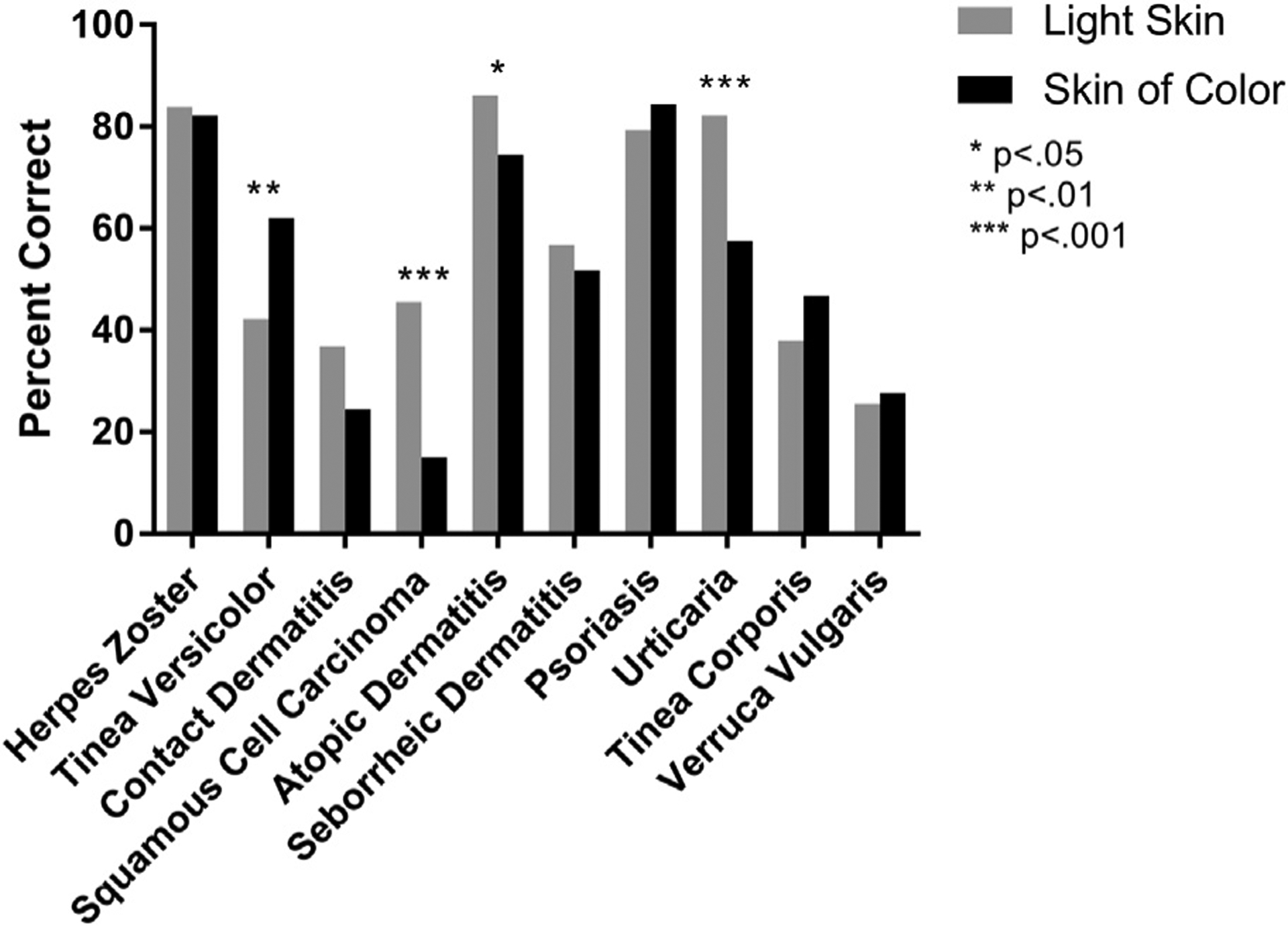

The conditions with the greatest disparity in visual diagnosis based on Fitzpatrick skin phototypes (Fitzpatrick IV-VI vs Fitzpatrick I-III) were squamous cell carcinoma (14.9% vs 45.6%, respectively; t(175) = 4.662; P < .0001), urticaria (57.5% vs 82.2%, respectively; t(175) = 3.712; P = .0003), and atopic dermatitis (74.4% vs 86.2%, respectively; t(175) = −1.975; P − .0495) (Fig 1). Nearly 34% of students misdiagnosed squamous cell carcinoma in SoC as melanoma, which may be explained by the students’ reliance on dark pigment alone as the feature of melanoma. Students were more likely to correctly identify tinea versicolor in patients with SoC compared with patients with lighter skin phototypes (62.1% correct vs 42.2%, respectively; t(175) = −2.681; P = .0082) (Fig 1). The increase in diagnostic accuracy for tinea versicolor likely involves the prominent pigmentary change in SoC. Although not all statistically significant, 3 of the 4 diseases more accurately diagnosed in SOC were infections such as tinea corporis and verruca vulgaris. The study was limited by an overall low response rate and the fact that each participant did not serve as his/her own control.

Fig 1.

Percentage correct by skin condition, stratified by Fitzpatrick skin phototype.

Our study showed that medical students were less accurate in diagnosing squamous cell carcinoma, atopic dermatitis, and urticaria in patients with SoC but were more accurate in diagnosing tinea versicolor in SoC. These findings highlight the need to present all dermatologic conditions in both light skin and SoC as part of a comprehensive dermatology curriculum.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Katrina D’Aquin, PhD, for guidance with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest:

Dr Murina is a speaker for AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Novartis. Ms Fenton; Ms Elliott; Mr Shahbandi; Mr Ezenwa; and Drs Morris, McLawhorn, Jackson, and Allen have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The findings of this study were reported at the Association of Professors of Dermatology Meeting in Chicago, IL on September 13, 2019.

IRB approval status: Reviewed and approved by Tulane IRB and University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center IRB (approval nos. 2018–2348 and 10264).

REFERENCES

- 1.Fourniquet SE, Garvie K, Beiter K. Exposure to dermatological pathology on skin of color increases physician and student confidence in diagnosing pathology in patients of color. FASEB J. 2019;33(suppl 1):606.18.30118321 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tripathi R, Knusel KD, Ezaldein HH, Scott JF, Bordeaux JS. Association of demographic and socioeconomic characteristics with differences in use of outpatient dermatology services in the United States demographic and SES differences in use of US outpatient dermatology services. JAMA Dermatol. 2018; 154(11):1286–1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buster KJ, Stevens EI, Elmets CA. Dermatologic health disparities. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30(1):53–59.viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buster K, Ezenwa E. Health disparities and skin cancer in people of color. Practical Dermatol. 2019;(April):38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stephanie W Medical student melanoma detection rates in white and African American skin using Moulage and standardized patients. Clin Res Dermatol. 2015;2(1):1–4. [Google Scholar]