Abstract

Background

Since the outbreak in China due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) various studies have been published describing olfactory and gustatory dysfunction (OGD).

Objective

The aim was to investigate the frequency and severity of OGD in SARS-CoV-2 (+) out-patients compared to controls with common cold/flu like symptoms and two negative RT-PCR.

Methods

A multicenter cross-sectional study on SARS-CoV-2-positive out-patients (n = 197) and controls (n = 107) from five Spanish Hospitals. Severity of OGD was categorized by visual analogue scale (VAS). Frequency and severity of the chemosensory impairment were analyzed.

Results

The frequencies of smell (70.1%) and taste loss (65%) were significantly higher among COVID-19 subjects than in the controls (20.6% and 19.6%, respectively). Simultaneous OGD was more frequent in the COVID-19 group (61.9% vs 10.3%) and they scored higher in VAS for severity of OGD than controls. In the COVID-19 group, OGD was predominant in young subjects 46.5 ± 14.5 and females (63.5%). Subjects with severe loss of smell were younger (42.7 years old vs 45.5 years old), and recovered later (median = 7, IQR = 5.5 vs median = 4, IQR = 3) than those with mild loss of smell. Subjects with severe loss of taste, recovered later in days (median = 7, IQR = 6 vs median = 2, IQR = 2), compared to those with mild loss.

Conclusion

OGD is a prevalent symptom in COVID-19 subjects with significant differences compared to controls. It was predominant in young and females subjects. Stratified analysis by the severity of OGD showed that more than 60% of COVID-19 subjects presented a severe OGD who took a longer time to recover compared to those with mild symptoms.

Keywords: Hyposmia, Anosmia, Ageusia, Taste loss, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Out-patients

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020 by the World Health Organization (OMS) [1]. To date, more than 5 million people (5,593,631 as of May 28th, 2020) have been diagnosed, and more than 350,000 deaths have been reported [1]. Although many people develop respiratory symptoms [2], a considerable number of cases are asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic with a larger incubation period (potentially lasting longer than 14 days), resulting in a large number of carriers [3]. This fact, associated with being highly transmissible by large drops, aerosolize and, possibly, by direct contact, contribute to its rapid spread [4, 5].

This pandemic situation has pushed the capacity of health systems to the limit and makes it necessary to consider early diagnosis suspicion for those who have mild symptoms and it is not possible to confirm the presence of the virus [6]. Since China’s initial anecdotal reports [7], there have been a growing number of studies describing a wide frequency range of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction (OGD) in COVID-19 patients, and guide recommendation for self-isolation in patients with OGD [8, 9].

Recent studies seem to show a trend that OGD is more frequent in a young [10] and non-hospitalized population [11, 12]. The aim of the present study was to investigate whether OGD is present in COVID-19 patients with mild disease evaluated in an ambulatory setting as compared to controls.

Materials and methods

Ethical issues

This observational study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clinic Barcelona (HCB/2020/0402) and Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa (02-20-188-023). Local Ethics Committee approvals for other Spanish Autonomous Regions were also obtained. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Study design

A multicenter prospective cross-sectional study on SARS-CoV-2 (+) from five Spanish University Hospitals from March 21st to April 18th, 2020.

Study population

The following inclusion criteria were considered: (a) for both groups, adults (≥ 18 years old) of any gender in an ambulatory setting, (b) COVID-19: subjects with positive RT-PCR for SARS-CoV-2; (c) controls: subjects with common cold/flu-like symptoms and two negative RT-PCR SARS-CoV-2. All participants were able to be interviewed and to answer the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria were: pregnancy, language barrier, psychiatric or neurocognitive impairment, and previous history of OGD (allergic rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, among others). All testing was performed with the highest regard for participant’s and examiner’s safety with appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

Diagnosis

SARS-CoV-2 infection was assessed by RT-PCR. Different molecular techniques were performed, including CobasTM6800 (E and ORF1b genes), Seegene™ (N, E and RdRp genes), and LightCyclerTM480 (E and RdRp genes). In a real-time PCR assay, a cycle threshold (CT) is defined as the number of cycles required for the fluorescent signal to cross the threshold. In our study, a positive result was considered when both analyzed genes were positive. If only one gene was positive with CT < 37, it was also considered positive. If CT was > 37, the exam was repeated in another platform. In this new analysis, if both genes were positive, it was considered a positive result, but if it was only one gene with CT > 37, it was considered inconclusive.

Outcomes

Demographics on gender and age were registered. A complete questionnaire exploring OGD was created and performed in-person. The questionnaire included four items: (a) a smell loss visual analogue scale (VAS, 0–10 cm, being 0 no smell loss and 10 maximum smell loss focusing on smell and food/drink flavor; (b) a taste loss VAS with the same score range and grouping where, to avoid confusion between taste and smell/flavor, real taste perceptions (salty, sweet, bitter, and sour/acidic) were emphasized; (c) a question about OGD symptoms onset (days before or after the other COVID-19 symptoms); and (d) a question about recovering from OGD (durations in days). Participants were asked about the timeline of the onset, duration, and the eventual recovery of the chemosensory symptoms. The VAS for sinonasal symptoms based on the EPOS guidelines classifies related symptoms in mild (VAS > 0–3), moderate (VAS > 3–7) and severe (VAS > 7–10) disease [13]. Due to limitations related to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, instrumental smell assessment, or chemical gustometry were not performed.

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation for the age, median and the interquartile range for continuous variables were calculated. The qualitative variables are expressed in frequencies and percentages. The normality of the continuous variables was evaluated through the Shapiro–Wilk test with a significance level of p = 0.01. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare categorical variables between COVID-19 patient’s vs controls. T Student test or Mann–Whitney U test helped to compare continuous variables. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare loss of smell and taste severity in the categorical variables and Kruskal–Wallis test in the continuous variables. Data management and statistical analysis were performed by means of SPSS vs. 21 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) with the alpha level set at 0.05.

Results

COVID-19 subjects and controls

A total of 197 COVID-19 subjects (mean age = 46.5 ± 14.5, range 21–89 years, 63.5% female) and 107 controls (mean age = 50.6 ± 16.6, range 20–88 years, 53.3% female) completed the survey. Demographics and clinical characteristics of both groups are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of COVID-19 subjects compared to controls in ambulatory setting

| Characteristics | COVID-19 (n = 197) | Control (n = 107) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 46.5 (14.5) | 50.6 (16.6) | 0.026 |

| Gender, female, N (%) | 125 (63.5) | 57 (53.3) | 0.084 |

| (a) Loss of smell | |||

| Frequency, N (%) | 138 (70.1) | 22 (20.6) | < 0.001 |

| Severity, VAS (0–10 cm), median [IQR] | 9 [3.2] | 5 [5.8] | < 0.001 |

| Mild (> 0–3 cm), N (%) | 8 (5.8) | 8 (36.4) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate (> 3–7 cm), N (%) | 32 (23.2) | 9 (40.9) | |

| Severe (> 7–10 cm), N (%) | 98 (71) | 5 (22.7) | |

| (b) Loss of taste | |||

| Frequency, N (%) | 128 (65) | 21 (19.6) | < 0.001 |

| Severity, VAS (0–10 cm), median [IQR] | 9 [3.8] | 3 [5] | < 0.001 |

| Mild (> 0–3 cm), N (%) | 8 (6.3) | 11 (52.4) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate (> 3–7 cm), N (%) | 36 (28.1) | 8 (38.1) | |

| Severe (> 7–10 cm), N (%) | 84 (65.6) | 2 (9.5) | |

| (c) Loss of smell and taste | |||

| Frequency, N (%) | 122 (61.9) | 11 (10.3) | < 0.001 |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, SD standard deviation, VAS visual analogue scale, IQR interquartile range

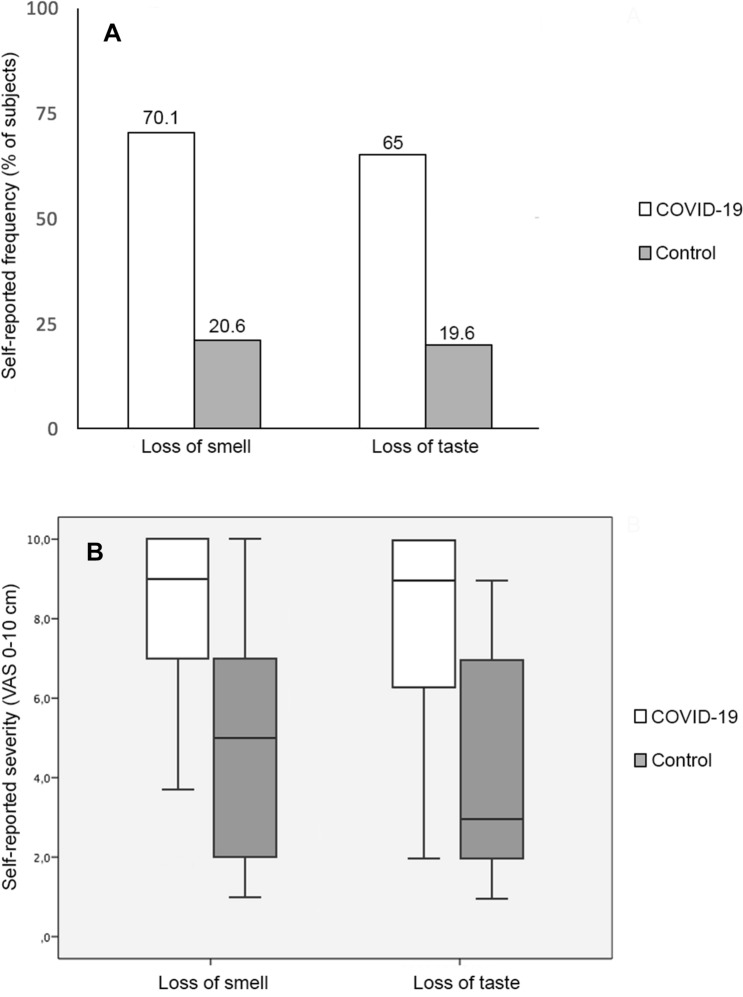

The frequencies of smell and taste loss were significantly higher among COVID-19 subjects (70.1% and 65%, p < 0.001) than in the control group (20.6% and 19.6%), respectively (Fig. 1a). Simultaneous OGD was more frequent in COVID-19 group (61.9%) compared to controls (10.3%) (p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

Frequency and severity of loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 subjects. a Self-reported frequency of smell and taste loss in COVID-19 subject’s vs controls; and b self-reported severity by visual analogue scale (VAS, 0–10 cm) of loss of smell and taste in COVID-19 subject’s vs controls

Both, the severity of loss of smell (median = 9, IQR = 3.2 vs median = 5, IQR = 5.8) and loss of taste (median = 9, IQR = 3.8 vs median = 3, IQR = 5) (p < 0.001) as measured by VAS were scored higher in COVID-19 subjects vs controls (Fig. 1b).

Characteristics of COVID-19 subjects by gender

From a total of 197 COVID-19 subjects 125 (63.5%) were females (mean age = 45.7 ± 14.2 years) and 72 (36.5%) were males (mean age = 47.8 ± 15 years) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 subjects with or without olfactory and gustatory dysfunction (OGD)

| Characteristics | Females (n = 125) | Males (n = 72) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 45.7 (14.2) | 47.8 (15) | 0.333 |

| (a) Loss of smell | |||

| Frequency, N (%) | 90 (72) | 48 (66.7) | 0.431 |

| Severity, VAS (0–10 cm), median [IQR] | 8 [10] | 6 [9.9] | 0.257 |

| Mild (> 0–3 cm), N (%) | 4 (4.4) | 4 (8.3) | 0.572 |

| Moderate (> 3–7 cm), N (%) | 20 (22.2) | 12 (25) | |

| Severe (> 7–10 cm), N (%) | 66 (73.3) | 32 (66.7) | |

| (b) Loss of taste | |||

| Frequency, N (%) | 89 (71.2) | 39 (54.2) | 0.016 |

| Severity, VAS (0–10 cm), median [IQR] | 7 [10] | 3.8 [8] | 0.014 |

| Mild (> 0–3 cm), N (%) | 5 (5.6) | 3 (7.7) | 0.791 |

| Moderate (> 3–7 cm), N (%) | 24 (27) | 12 (30.8) | |

| Severe (> 7–10 cm), N (%) | 60 (67.4) | 24 (61.5) | |

| (c) Loss of smell and taste | |||

| Frequency, N (%) | 85 (68) | 37 (51.4) | 0.021 |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, SD standard deviation, VAS visual analogue scale, IQR interquartile range

The frequencies of simultaneous OGD were significantly higher among females (68%) than in the males group (51.4%, p = 0.021), along with loss of taste (71.2% vs 54.2%, p = 0.016). However, no differences were found in loss of smell (72% vs 66.7%, p = 0.431). As for the severity, females VAS scored higher in loss of taste than males (median = 7, IQR = 10 vs median = 3.8, IQR = 8, p = 0.014), with no differences in loss of smell.

Stratification by loss of smell severity

A total of 138 COVID-19 subjects reported olfactory dysfunction of which 8 (5.8%) had mild, 32 (23.2%) moderate, and 98 (71%) severe smell loss. The profile of subjects with severe loss of smell was younger (42.7 years old vs 45.5 years old, p = 0.045), and recovered later (median = 7, IQR = 5.5 vs median = 4, IQR = 3, p = 0.009) than those with mild loss of smell. However, no differences by severity were found in loss of smell manifested as a first symptom, recovery-rate, and gender (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of COVID-19 subjects stratified by severity of loss of smell

| Characteristics | Non-smell loss (VAS 0 cm) (n = 59) | Mild (VAS > 0–3 cm) (n = 8) | Moderate (VAS > 3–7 cm) (n = 32) | Severe (VAS > 7–10 cm) (n = 98) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 50.6 (15.6) | 45.5 (13.8) | 50.7 (16.7) | 42.7 (12) | 0.045 |

| Gender, female, N (%) | 35 (59.3) | 4 (50) | 20 (62.5) | 66 (67.3) | 0.574 |

| As first symptom, N (%) | 1 (12.5) | 5 (15.6) | 15 (15.3) | 0.138 | |

| Prior to other symptoms, days, median [IQR] | 5 [0] | 1 [1] | 2 [2.5] | 0.499 | |

| Recovery, N (%) | 5 (62.5) | 11 (34.4) | 36 (36.7) | 0.530 | |

| Recovery time, days, median [IQR] | 4 [3] | 6 [5.8] | 7 [5.5] | 0.009 |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, SD standard deviation, VAS visual analogue scale, IQR interquartile range

*p value was obtained by severity of smell loss excluding the non-smell loss group

Stratification by loss of taste severity

A total of 128 COVID-19 subjects reported taste dysfunction of which 8 (6.3%) had mild, 36 (28.1%) moderate, and 84 (65.6%) severe loss of taste. Some differences were observed compared to findings by stratifying for loss of smell severity. No differences by severity were found by age or gender, in taste loss manifested as a first symptom, and recovery-rate. However, patients with severe loss of taste recovered later in days (median = 7, IQR = 6 vs median = 2, IQR = 2, p = 0.021), compared to those with mild loss (Table 4).

Table 4.

Characteristics of COVID-19 subjects stratified by severity of taste loss

| Characteristics | No taste loss (VAS 0 cm) (n = 69) | Mild (VAS > 0–3 cm) (n = 8) | Moderate (VAS > 3–7 cm) (n = 36) | Severe (VAS > 7–10 cm) (n = 84) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 49.1 (16.5) | 46.1 (12.3) | 48.2 (14.5) | 43.6 (12.4) | 0.209 |

| Gender, female, N (%) | 36 (52.2) | 5 (62.5) | 24 (66.7) | 60 (71.4) | 0.792 |

| As first symptom, N (%) | 1 (12.5) | 7 (19.4) | 12 (14.3) | 0.336 | |

| Prior to other symptoms, days, median [IQR] | 5 [0] | 1.5 [1.8] | 2.5 [4.8] | 0.166 | |

| Recovery, N (%) | 2 (25) | 12 (33.3) | 28 (33.3) | 0.701 | |

| Recovery time, days, median [IQR] | 2 [2] | 7 [6] | 7 [6] | 0.021 |

COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019, SD standard deviation, VAS visual analogue scale, IQR interquartile range

*p value was obtained by severity of taste loss excluding the no taste loss group

Discussion

The main findings of our study were: (1) subjects with diagnosed COVID-19 were younger, with similar gender, and their olfactory and taste dysfunction was sixfold more common than in control subjects when the impairment was of both senses; (2) more than half of COVID-19 subjects presented loss of smell (70.1%) or taste (65%), in > 60% both. One out of seven subjects presented loss of smell (15.2%) or loss of taste (15.6%) as the first symptom of the disease; (3) females had more frequent and more severe loss of taste than males, and more frequently simultaneous OGD; and (4) among COVID-19 subjects with OGD, one out of two had a severe loss of smell and/or taste and late recovery than patients with a milder dysfunction. Moreover, subjects with severe loss of smell were younger than those with mild loss.

In our study, a self-reported ordinal quantitative assessment of the chemosensory dysfunction was performed by a validated VAS scale for smell and taste loss separately. Tong et al. [8] described in a recent meta-analysis of OGD a 52.7% prevalence of smell loss and 43.9% of taste loss in COVID-19 subjects. In subgroup analyses of olfactory dysfunction, they demonstrated that studies using validated instruments (such as the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) [14], smell component of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), short version of the Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorders–Negative Statements [15], and the COVID-19 Anosmia Reporting Tool [16]) showed an 86.60% smell loss prevalence compared to 36.64% in studies which used non-validated instruments [8]. However, only the study of Lechien et al. [15] used a validated measure to assess gustatory dysfunction with the taste component of the NHANES.

In our results, the frequencies of loss of smell (70.1%), loss of taste (65%) or both (61.9%) in the COVID-19 group are similar to those found by Menni et al. [6], where they reported a 64.76% frequency of OGD, compared with 22.68% on those who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

Our findings on OGD, being predominant in younger subjects and females, were similar to those reported by Lee et al. [10]. The explanation of this demographic trend is still not well understood. In the normal population, the olfactory dysfunction (OD) and gustatory dysfunction (GD) are commonly described more frequently with older age [17, 18], while females outperformed males for taste [18] and smell [19]. In post-viral OD, a higher prevalence in middle-aged women (age 40–69 years) has been described [20]. Concerning gustatory dysfunction (GD), taste seems to decrease proportionally to the degree of OD regardless of the underlying cause (post-traumatic, idiopathic, post-infectious or chronic rhinosinusitis) [21] and persisted after age-correction [22]. There have been hypotheses that chemical senses intimately interact, associating impaired olfactory function with decreased gustatory function. In contrast to other sensory modalities, they do not tend to show compensatory mechanisms, but rather mutual weakening [22]. A potential explanation is that they did not function individually sharing a common processing [23]. A greater analysis regarding the aetiopathogenesis of the OGD in COVID-19 infection will need further research.

In our study, COVID-19 subjects reported most commonly their loss of smell and loss of taste as severe (71% and 65.6%) rather than mild (5.8% and 6.3%). Moreover, a shorter recovery time was observed in those patients with mild OGD (VAS > 0–3 cm). These results are in agreement with those reported by London et al. [24] in post-infectious OD, where microsmic patients were more than twice as likely to improve into the normal range of smell than anosmic patients. This was also found by Cavazzana et al. [25], showing that higher/better initial smell scores using Sniffin’ Sticks were associated with higher probability of later normosmia.

Our study had the following strengths: (1) RT-PCR confirmed positive COVID-19 and control group matched by age with common cold/flu-like symptoms and two negative RT-PCR; (2) in-place personal interview using PPE allowing a better comprehension of the questionnaire, emphasizing the difference between flavor and taste to avoid confusion; (3) VAS scores for both smell and taste loss was obtained, allowing a self-reported ordinal quantitative assessment of the sensory dysfunction. On the other hand, our study also had limitations: (1) suboptimal sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR on nasopharyngeal swab might have led to misclassification and diagnostic bias (false positives and/or false negatives); (2) lack of respiratory viruses RT-PCR test detection for the control group (rhinovirus, influenza, parainfluenza, among others); (3) due to unnecessary safety risk for physicians and discomfort for patients due to their medical condition, no validated questionnaire, instrumental olfaction or gustatory assessment were considered; and (4) COVID-19 survey was measured at only one point related to its onset date, although further follow-up will be performed.

Conclusions

OGD is a prevalent symptom in COVID-19 ambulatory subjects, with higher frequencies and severity of the chemosensory impairment compared to controls (other respiratory viruses), this difference being more outstanding in the loss of both senses together. In the COVID-19 group, OGD was predominant in younger subjects and females. Stratified analysis by the severity of OGD showed that more than 60% of COVID-19 subjects presented a severe OGD that took a longer time to recover as compared to those with mild symptoms. Concerning loss of smell severity, the subjects with higher VAS scores were younger. Further studies will be needed to provide explanations for these chemosensory impairments.

Author contributions

AID and MJRL: designed, collect data and analyze results and final approval of the manuscript. IA and JM: design the questionnaire, prepared and review the manuscript and final approval of the manuscripts. CCE, CCH, IMV: collect data and final approval of the manuscript. MBS: review the manuscript and final approval of the manuscripts. GCC: collaborate with the revisions of the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for the present study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Isam Alobid: Consultant for Roche, Novartis, Mylan, Menarini, MSD. Joaquim Mullol: member of national or international advisory boards, received speaker fees, or funding for clinical trials and research projects from ALK, AstraZeneca, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Glenmark, Menarini, Mitsubishi-Tanabe, MSD, Mylan-MEDA Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, SANOFI-Genzyme, UCB Pharma, and Uriach Group. The other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was supported by the Commission of Rhinology and Allergy, Spanish ENT Society (SEORL-CCC).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

María Jesús Rojas-Lechuga and Adriana Izquierdo-Domínguez have equally contributed as main authors.

Joaquim Mullol and Isam Alobid have equally contributed as senior authors.

Contributor Information

Joaquim Mullol, Email: jmullol@clinic.cat.

Isam Alobid, Email: isamalobid@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): situation report-118. Geneva: World Health Organization reports. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports. Accessed 28 May 2020

- 2.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vukkadala N, Qian ZJ, Holsinger FC, Patel ZM, Rosenthal E (2020) COVID- 19 and the otolaryngologist - preliminary evidence-based review. Laryngoscope. 10.1002/lary.28672 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Wu Z, McGoogan JM (2020) Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Zhang J, Wu S, Xu L (2020) Asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 as a concern for disease prevention and control: more testing, more follow- up. Biosci Trends. 10.5582/bst.2020.03069. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Menni C, Valdes AM, Freidin MB, Sudre CH, Nguyen LH, Drew DA et al (2020) Real-time tracking of self-reported symptoms to predict potential COVID-19. Nat Med. 10.1038/s41591-020-0916-2. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q et al (2020) Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Tong JY, Wong A, Zhu D, Fastenberg JH, Tham T (2020) The prevalence of olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 10.1177/0194599820926473. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Izquierdo-Domínguez A, Rojas-Lechuga MJ, Mullol J, Alobid I (2020) Olfactory dysfunction in the COVID-19 outbreak. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 10.18176/jiaci.0567. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Lee Y, Min P, Lee S, Kim SW. Prevalence and duration of acute loss of smell or taste in COVID-19 patients. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(18):e174. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan CH, Faraji F, Prajapati DP, Boone CE, DeConde AS (2020) Association of chemosensory dysfunction and Covid-19 in patients presenting with influenza-like symptoms. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10.1002/alr.22579. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Giacomelli A, Pezzati L, Conti F, Bernacchia D, Siano M, Oreni L et al (2020) Self-reported olfactory and taste disorders in patients with severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 infection: a cross-sectional study. Clin Infect Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciaa330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, Hellings PW, Kern R, Reitsma S, et al. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2020. Rhinology. 2020;58(Suppl S29):1–464. doi: 10.4193/Rhin20.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moein ST, Hashemian SMR, Mansourafshar B, Khorram-Tousi A, Tabarsi P, Doty RL (2020) Smell dysfunction: a biomarker for COVID-19. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 10.1002/alr.22587. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, De Siati DR, Horoi M, Le Bon SD, Rodriguez A et al (2020) Olfactory and gustatory dysfunctions as a clinical presentation of mild-to-moderate forms of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19): a multicenter European study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 10.1007/s00405-020-05965-1. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Kaye R, Chang CWD, Kazahaya K, Brereton J, Denneny JC III (2020) COVID-19 anosmia reporting tool: initial findings. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 10.1177/0194599820922992. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Mullol J, Alobid I, Mariño-Sánchez F, Quintó L, de Haro J, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, et al. Furthering the understanding of olfaction, prevalence of loss of smell and risk factors: a population-based survey (OLFACAT study) BMJ Open. 2020;2(6):e001256. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis BN, Welge-Luessen A, Brämerson A, Bende M, Mueller CA, Nordin S, et al. “Taste Strips” - a rapid, lateralized, gustatory bedside identification test based on impregnated filter papers. J Neurol. 2009;256(2):242–248. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0088-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Zhang C, Xia X, Yang Y, Zhou C. Effect of gender on odor identification at different life stages: a meta-analysis. Rhinology. 2019;57(5):322–330. doi: 10.4193/Rhin19.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sugiura M, Aiba T, Mori J, Nakai Y. An epidemiological study of postviral olfactory disorder. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1998;538:191–196. doi: 10.1080/00016489850182918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Migneault-Bouchard C, Hsieh JW, Hugentobler M, Frasnelli J, Landis BN. Chemosensory decrease in different forms of olfactory dysfunction. J Neurol. 2020;267(1):138–143. doi: 10.1007/s00415-019-09564-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landis BN, Scheibe M, Weber C, Berger R, Brämerson A, Bende M, et al. Chemosensory interaction: acquired olfactory impairment is associated with decreased taste function. J Neurol. 2010;257(8):1303–1308. doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5513-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lundström JN, Gordon AR, Wise P, Frasnelli J. Individual differences in the chemical senses: is there a common sensitivity? Chem Senses. 2012;37(4):371–378. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjr114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.London B, Nabet B, Fisher AR, White B, Sammel MD, Doty RL. Predictors of prognosis in patients with olfactory disturbance. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:159–166. doi: 10.1002/ana.21293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cavazzana A, Larsson M, Münch M, Hähner A, Hummel T. Postinfectious olfactory loss: a retrospective study on 791 patients. Laryngoscope. 2018;128(1):10–15. doi: 10.1002/lary.26606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]