Abstract

Objective

Because internal medicine hospitalist programs were developed to address issues in medicine such as a need to improve quality, improve efficiency, and decrease healthcare cost, obstetrical (OB) hospitalist models were developed to address needs specific to the obstetrics and gynecology field. Our objective was to compare outcomes measured by occurrence of safety events before and after implementation of an OB hospitalist program in a mid-sized OB unit.

Methods

From July 2012 to September 2014, 11 safety events occurred on the labor and delivery floor. A full-time OB hospitalist program was implemented in October 2014.

Results

From October 2014 to December 2016, there was 1 safety event associated with labor and delivery.

Conclusion

It has been speculated that implementation of an OB hospitalist model would be associated with improved maternal and neonatal outcomes; our regional OB referral hospital demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in OB safety events after the OB hospitalist program implementation.

Key Words: obstetrical laborist, patient safety, hospitalist model

The internal medicine hospitalist model was developed as a response to a growing need to improve quality metrics, increase efficiency, and decrease health care costs.1,2 Similar components influence the use of internal medicine hospitalist programs today. According to Pham et al.,3 market pressures, rising health care costs, and medicolegal pressures were associated with the use of hospitalists in the inpatient system. The hospitalist model has been shown to improve efficiency, most often demonstrated by measurement of length of stay and total hospital costs.4 Studies published from the internal medicine hospitalist model have had varied results from reportable improvement5,6 to worse outcomes7,8 and some with no change at all.9–11 Patient satisfaction with a hospitalist was also a concern but appears no lower than patient satisfaction with their primary care provider.10,12

Although the internal medicine hospitalist model was implemented in the 1990s,2 obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) laborist and hospitalist models were first described in 2003.2,13 By 2010, close to 40% of obstetrical (OB) units had some type of OB hospitalist program in place.14 The Society of OB/GYN Hospitalists defines an OB/GYN hospitalist as “an obstetrician/gynecologist who has focused their professional practice on care of the hospitalized woman” and a laborist as “an obstetrician/gynecologist who has focused their professional practice on the care of women in labor and delivery.”2 In 2012, 1 to 2 new hospitalist programs were being added each month.1 This model is ever evolving, with different terms OB hospitalist, laborist, and OB/GYN hospitalist being used interchangeably. Although there are small variations between these terms, OB hospitalist will primarily be used to describe these roles.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee recognizes the implementation of OB hospitalist programs as a potential way to address issues in the OB/GYN field such as physician burnout, unpredictable work schedules, and most importantly patient safety. Dissatisfaction in the OB/GYN field is happening earlier than before.13 The OB hospitalist models allow more physician control over work schedules and improvement of physician lifestyle.13,15 Several studies report that OB hospitalists have high career satisfaction, a markedly different result from their colleagues in the OB/GYN field.1,15

The continuous OB/GYN coverage on labor and delivery is a mandated part of the ACGME requirement for the teaching of residents and fellows. Great opportunities exist in the application of the OB hospitalist model within academic settings. Obstetrical hospitalists are an untapped resource which, when developed, benefits patients, providers, and hospitals. The program creates new revenue streams to support the program and extend existing faculty resources for better on-site supervision.

Although there is little research on the internal medicine hospitalist models, there is even less research about OB hospitalist models and the impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes. It is important to note that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has supported the progress and development of OB hospitalist programs.16,17 Many have speculated that the OB hospitalist model of care may improve maternal and neonatal outcomes.16 Srinivas and Lorch16 suggest evaluation of OB hospitalist models by assessing timeliness, responsiveness, and frequency of patient assessment. Pettker et al.18 reported improvements in staff perception of safety culture with OB hospitalist implementation. Iriye et al.17 showed a 27% reduction in cesarean delivery with the OB hospitalist model as compared with the traditional model.19 Although these studies are highlighting important information, currently, no published studies are available that report outcomes after the implementation of an OB hospitalist model.16,17 By tracking and monitoring safety events, prevention of error may be possible. The objective of this study was to compare safety events before implementation of an OB hospitalist program to safety events after implementation at our regional OB referral hospital.

METHODS

As a quality improvement project, a retrospective chart review of safety events on labor and delivery at our regional OB referral hospital was conducted. This study was directly related to quality improvement at our hospital, and all de-identified data de-identified were reviewed as part of the institutional quality improvement process; thus, the study was exempt from institutional review board approval per institutional institutional review board policy. The mid-sized OB unit, with approximately 3500 deliveries per year, is embedded in a 456-bed acute care facility. Of those beds, 76 are devoted to women services. At our institution, a safety event was defined as “an event considered to be one or more of the following: a deviation from generally accepted practice or process affecting the patient, there were no preventable known complications, or the event was determined to be preventable”20 and can be reported through a hotline by any staff member. Safety events were monitored and assigned a level of severity by an appointed safety event review team made up of multidisciplinary hospital leaders. Severity level ranged from a near miss event to maternal or fetal death. An action plan was created for each safety event, healthcare team members were given re-education, if applicable, and progress of action plan was monitored by the safety event review team.

The full-time OB hospitalist program was implemented in October of 2014, which consists of 4 full-time OB hospitalists who staff the unit on a continuous basis. These four positions where added as a new resource to the labor and delivery unit. The traditional triage unit functions as an emergency department. With the start of the program, medical staff rules were enacted requiring all privileged obstetricians or their designee, to exam and evaluate their OB patients who presented to the OB emergency department. In their absence, the OB hospitalist would step in and provide patient care services. Other OB hospitalist duties included call coverage for solo staff obstetricians, assistance to the primary obstetrician and nursing staff in OB emergencies and/or complicated operative cases, and supervising resident physicians.

Labor and delivery safety events are monitored as part of the ongoing quality improvement process, providing access to the data preimplementation and postimplementation of the OB hospitalist program. The preimplementation time period was from July 2012 to September 2014. The postimplementation period was from October 2014 to December 2016. Safety events were reviewed by 3 independent investigators and grouped into the following 3 ways: by date, by type of event, and by probable causative factor.

RESULTS

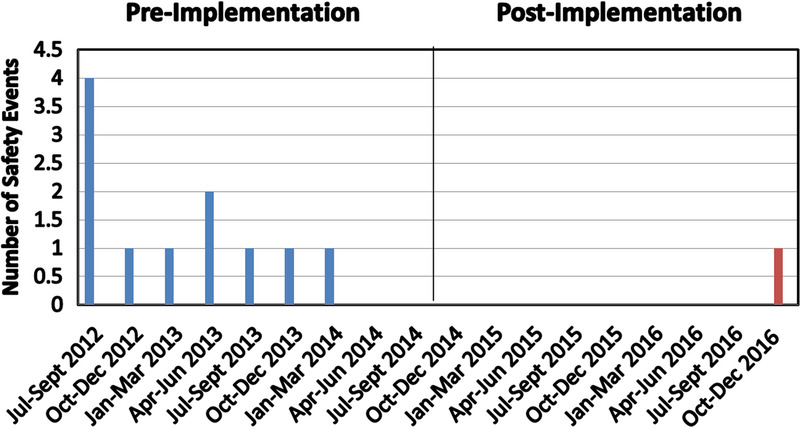

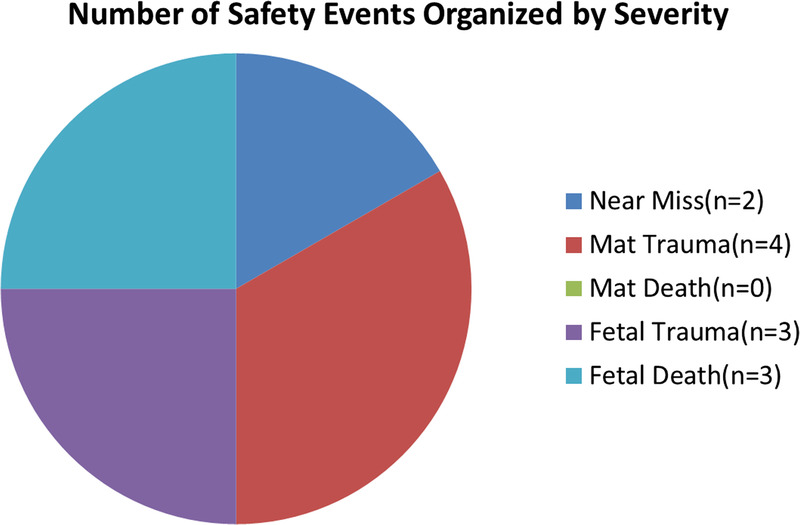

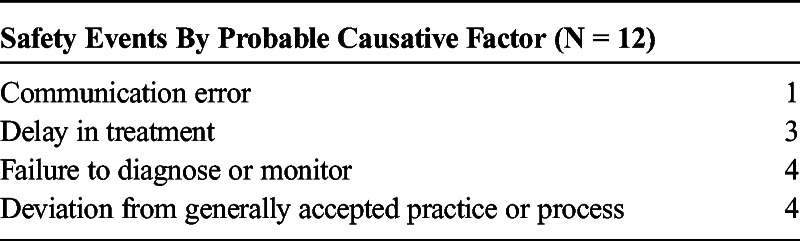

In the preimplementation program, there were 11 serious safety events as compared with 1 safety event in the postimplementation period. A sign test was performed and demonstrated that the laborist program as the intervention improved safety on out unit (P = 0.0032, Fig. 1) with statistical significance. The data were also tracked by date (Fig. 1, Table 1) and grouped according to the specific type of event (Table 2) and severity (Fig. 2). Finally, safety events were grouped by probable causative factor (Table 3).

FIGURE 1.

Number of safety events organized by date.

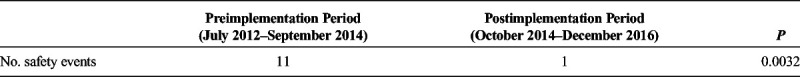

TABLE 1.

Number of Safety Events in the Preimplementation and Postimplementation Period

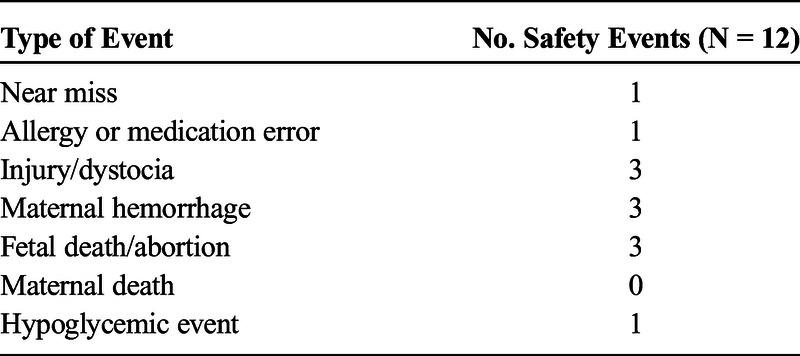

TABLE 2.

Number of Safety Events by Type of Event

FIGURE 2.

Number of safety events organized by severity.

TABLE 3.

Number of Safety Events by Probable Causative Factor

DISCUSSION

Before implementing the OB hospitalist program, care was fragmented and a lack of standardization in delivery of health care services was present. Although we had an existing academic physician in house, there was no formalized role in the management of the private patients. Economic competition made validation of such a relationship politically difficult. Furthermore, our unit at baseline promoted unnecessary variation in care due to local culture. It is important to note that there is not a mandate for the academic teaching physicians to be board certified, and it is common for junior faculty members to be active board candidates.

System redesign, with the application of industrial engineering in healthcare, such as LEAN and Six Sigma, drives quality.21 The laborist program was the system redesign that promoted the change in the local culture. Furthermore, OB hospitalists have been shown to be the driving force in the standardization of obstetric care,16 which was the case within our program. It is well known that standardization is a key driver in health care quality, and at best, only approximately 55% of adults in the United States received health care with the guidelines.22

The Institute of Medicine has outlined the following 6 principles for quality care: safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable.23 Our redesigned system, with the OB laborist at the center, fully implemented these 6 ideals on the unit. Full-time OB hospitalists provided patients with immediate evaluation and early recognition of critical clinical events and provided management in high-stakes clinical situations. All unscheduled OB patients presenting to the OB unit were all seen by a board-certified obstetrician within 1 hour of presenting to the unit. Care coordination occurred between the primary obstetrician and the OB hospitalist keeping the focus patient centered.

When patients were surveyed about OB hospitalists, responses were positive to having a physician immediately available for obstetric counsel and care,1 a surprising finding to those opposing OB hospitalist models due to a fear of a decrease in patient satisfaction. Another common opposing argument is that OB hospitalist programs are costly. Obstetrical hospitalist programs may actually reduce healthcare cost due to improvement of labor and delivery coverage.18,20 Olson et al.1 reported that 70% of paid malpractice claims were categorized as delayed response of the physician and may have been avoided with better physician coverage.1,21 Olson et al.1 reported a US $48.5 million in savings for 5 years after implementation of a safety intervention, which included initiation of a hospitalist program. In our experience, we have found the OB hospitalist program financially successful.

CONCLUSIONS

Although it has been speculated that an OB hospitalist model would be associated with improved maternal and neonatal outcomes,16 our regional OB referral hospital demonstrated a statically significant decline in safety events after the OB hospitalist program implementation. The strength of our study is that it is the first of its kind to demonstrate application of an OB hospitalist program and its impact on acute OB emergencies. The weakness lies in the fact that this is the experience at one institution, emphasizing the need for continued monitoring and reporting of safety events by multiple sources to have complete understanding of the impact that an OB hospitalist program may provide for patient safety.

Footnotes

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Olson R Garite TJ Fishman A, et al. Obstetrician/gynecologist hospitalists: can we improve safety and outcomes for patients and hospitals and improve lifestyle for physicians? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messler J, Whitcomb WF. A history of the hospitalist movement. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42:419–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pham HH Devers KJ Kuo S, et al. Health care market trends and the evolution of hospitalist use and roles. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:101–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Med. 2011;9:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachter RM, Goldman L. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287:487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auerbach AD Wachter RM Katz P, et al. Implementation of a voluntary hospitalist service at a community teaching hospital: improved clinical efficiency and patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:859–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bellet PS, Whitaker RC. Evaluation of a pediatric hospitalist service: impact on length of stay and hospital charges. Pediatrics. 2000;105(3 Pt 1):478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somekh NN Rachko M Husk G, et al. Differences in diagnostic evaluation and clinical outcomes in the care of patients with chest pain based on admitting service: the benefits of a dedicated chest pain unit. J Nucl Cardiol. 2008;15:186–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roy CL Liang CL Lund M, et al. Implementation of a physician assistant/hospitalist service in an academic medical center: impact on efficiency and patient outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2008;3:361–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wachter RM Katz P Showstack J, et al. Reorganizing an academic medical service: impact on cost, quality, patient satisfaction, and education. JAMA. 1998;279:1560–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein MD Hanson S Tammaro D, et al. Economic effects of community versus hospital-based faculty pneumonia care. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:774–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halpert AP Pearson SD LeWine HE, et al. The impact of an inpatient physician program on quality, utilization, and satisfaction. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6:549–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstein L. The laborist: a new focus of practice for the obstetrician. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:310–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivas SK Shocksnider J Caldwell D, et al. Laborist model of care: who is using it? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funk C Anderson BL Schulkin J, et al. Survey of obstetric and gynecologic hospitalists and laborists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203:177 e171–e174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivas SK, Lorch SA. The laborist model of obstetric care: we need more evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207:30–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iriye BK Huang WH Condon J, et al. Implementation of a laborist program and evaluation of the effect upon cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:251 e251–e256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettker CM Thung SF Raab CA, et al. A comprehensive obstetrics patient safety program improves safety climate and culture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204:216 e211–e216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Improvement ACOG, Practice ACOG. Committee Opinion No. 657: The Obstetric and Gynecologic Hospitalist. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e81–e85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Services AR. Principles of Highly Reliable Care: Reduction of Harm Through the Event Review Process. 2016.

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. LEAN and Six Sigma. Health IT Tools and Resources. Available at: https://healthit.ahrq.gov/health-it-tools-and-resources/workflow-assessment-health-it-toolkit/all-workflow-tools/lean-six-sigma. Accessed August 31, 2016.

- 22.McGlynn EA Asch SM Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Institute of Medicine US Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chiasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]