Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy is often accompanied by active subretinal fluid leakage and associated diffuse atrophic retinal pigment epithelium alterations. Treatment results in posterior cystoid retinal degeneration resolution in less than half of the cases, and final visual outcome remains poor even after posterior cystoid retinal degeneration resolution. A degenerative process may underlie posterior cystoid retinal degeneration development, causing retinal tissue loss, and irreversible vision loss.

Key words: chronic central serous chorioretinopathy, posterior cystoid macular degeneration, photodynamic therapy, treatment

Abstract

Purpose:

To assess clinical characteristics and visual outcome in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy patients with posterior cystoid retinal degeneration (PCRD).

Methods:

Patients' medical records were reviewed retrospectively in 62 cases (83 eyes, mean age = 59 years, 88% male). Data were collected at central serous chorioretinopathy diagnosis, at PCRD manifestation, and at final visit. All treatment modalities were reviewed. Main outcome measures were treatment efficacy in achieving PCRD resolution, and final best-corrected visual acuity.

Results:

In 63 eyes (76%), subretinal fluid was present at first PCRD manifestation, whereas fluorescein angiography showed active focal or diffuse leakage in 65 eyes (78%). Seventy-six eyes (81%) received treatment, and PCRD had resolved completely in 31 eyes (37%) at the final visit. Photodynamic therapy was most successful in achieving a complete PCRD resolution. Best-corrected visual acuity did not improve, even after complete PCRD resolution (mean baseline best corrected visual acuity = 69 ± 19, and mean final best corrected visual acuity = 67 ± 20 ETDRS letters [20/40 and 20/50 in Snellen equivalent respectively], P = 0.354).

Conclusion:

Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration is a relatively common finding in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy, which is often accompanied by active subretinal fluid leakage. Treatment may be beneficial to stop the subretinal fluid leakage component, but is less likely to result in a complete PCRD resolution and/or a best-corrected visual acuity improvement.

Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy (cCSC) is characterized by a persistent or intermittent subretinal serous leakage, presence of a serous neuroretinal detachment, and diffuse irregularities and atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE).1 Patients with cCSC may have a decreased vision-related quality of life and the disease is associated with progressive vision loss.2,3 Variability exists in the anatomical abnormalities among patients with cCSC, which may reflect the progression or stage of the disease.4 Besides chronic subretinal fluid (SRF) leakage, most cCSC patients show more extensive and/or multifocal RPE detachments and atrophic RPE changes in comparison to acute, self-limiting CSC.5 In contrast, acute central serous chorioretinopathy (aCSC) is characterized by an acute onset of a neurosensory detachment that often shows spontaneous resolution with a full recovery of vision, with little atrophic RPE changes.

A considerable number of cCSC patients show an extensive and presumably severe disease phenotype with diffuse atrophic RPE alterations (DARA), numerous “hot spots” of leakage on fluorescein angiography (FA), subretinal fibrin deposits, and/or occasionally posterior cystoid retinal degeneration (PCRD) at first presentation.6–10 These severe cCSC cases seem to form a distinct entity within the spectrum of CSC with the worst visual prognosis.6 Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration, first described by Piccolino et al in 2008,10 in particular was shown to be present in up to 35% of severe cCSC cases.6

In contrast to cystoid macular edema, which is generally associated with vascular hyperpermeability and active leakage, presence of PCRD as seen in cCSC may have a more degenerative origin related to the primary choroidopathy and RPE dysfunction.9 For example, in contrast to retinal vascular diseases with secondary cystoid macular edema, there seems to be no vascular endothelial growth factor-driven mechanism involved in PCRD, because antivascular endothelial growth factor medication was shown to be ineffective in PCRD.11 The recently described entity of “peripapillary pachychoroid syndrome,” which is characterized by peripapillary intraretinal cystoid changes, belongs to the pachychoroid disease spectrum just like CSC, with involvement of hyperpermeable choroidal vessels, that do not respons to intravitreal anti-VEGF either.12

Little is known about the etiology of PCRD. The development of PCRD may be explained at least partially by the hyperpermeability of choroidal vessels and the dysfunctional outer blood–retina barrier of the RPE, which is a characteristic of cCSC and other pachychoroid associated disease, even though PCRD can occur in the absence of active SRF leakage.9,10 As PCRD has been associated with a severely reduced visual acuity, resolution of PCRD is desirable.9,11 However, at present only a few relatively small studies are available on the clinical characteristics and treatment of PCRD in cCSC.9–11,13,14

The purpose of the present study is to describe the clinical characteristics on multimodal imaging in cCSC patients with PCRD, to review the outcome of treatments, especially for photodynamic therapy (PDT), and to assess the final visual outcome.

Materials and Methods

Patients were included for this study from three Dutch tertiary referral centers: Department of Ophthalmology at Leiden University Medical Center (Leiden, the Netherlands), Rotterdam Eye Hospital (Rotterdam, the Netherlands), and Radboud University Medical Center (Nijmegen, the Netherlands). This study was approved by the respective institutional review boards at the participating centers and was performed in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were included when visual complaints existed for over 6 months. Chronic CSC was defined according to a previous definition: evidence of persistent SRF for at least 3 months, RPE window defects and at least one “hot spot” of focal leakage on FA, and corresponding hyperfluorescent zones on indocyanine green angiography when available.3 All cases had cCSC-associated PCRD at some point during follow-up. Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration was recognized on optical coherence tomography (OCT) according to a previous definition by Piccolino et al,10 as intraretinal spaces separated by reflective tissue from the RPE which were detected within the temporal vascular arcades. Patients were excluded when intraretinal cystoid abnormalities were caused by other retinal or choroidal vascular abnormalities, such as (secondary) choroidal neovascularization. We also excluded patients with cystoid degeneration caused by trauma, evident epiretinal membrane, retinoschisis, and degeneration due to previous thermal laser treatment.

The medical charts were evaluated and information was collected concerning general medical background and steroid use, and diagnosis-related data including: date of CSC diagnosis, date of PCRD determination, fellow eye diagnosis, follow-up duration, treatment modalities and treatment effect, and best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) at diagnosis and at final visit. Best-corrected visual acuity which was originally assessed with a Snellen chart was converted to early treatment of diabetic retinopathy study (ETDRS) letters for further analysis.15 The location of PCRD was assessed and reported as: adjacent to the temporal side of the optic disc (peripapillary region), between the optic disc and the foveal region without peripapillary or foveal involvement (papillomacular region), covering the fovea, and elsewhere in the posterior pole. Treatment was considered effective only when there was a complete resolution of SRF and PCRD.

Clinical Examinations

Subjects were included when ophthalmologic and multimodal imaging examinations were available at diagnosis and during follow-up. Minimum available multimodal imaging examination included either time-domain OCT (Cirrus HD-OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec or OCT-HS100; Canon, Inc, Tokyo, Japan) or spectral-domain OCT (Spectralis HRA + OCT; Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) at the moment of PCRD manifestation and at final visit; and an FA (Topcon Corp, Spectralis HRA + OCT, or Carl Zeiss Meditec) after PCRD manifestation. Indocyanine green angiography (Topcon Corp, Heidelberg Spectralis HRA + OCT, or Carl Zeiss Meditec) was performed when a choroidal neovascularization had to be ruled out. The following characteristics were determined on FA imaging: presence of active leakage, type of leakage (focal vs. diffuse), and the area of DARA associated with PCRD. The extent of DARA area was quantified using available caliper measurement tools on FA equipment and expressed in number of optic disc diameters (DD).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS software for Windows, version 23 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Continuous numerical data were compared using a paired or unpaired Student's t-test. Categorical data were analyzed using a chi-square test. A COX proportional hazard model was computed to predict the effect size of multiple clinical and patient characteristics on complete resolution of PCRD. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for each risk factor according to a univariate and multivariate analysis. For all tests, a P-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

In total, 62 patients (83 eyes, 73 [88%] men) were included for analysis (see Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/IAE/B128). The mean age at first documented PCRD manifestation was 59 years (range: 36–80 years). The mean time between cCSC diagnosis and PCRD manifestation was 61 months (range: 0–347 months). Twenty-one cases had bilateral PCRD. General medical background in the study cases was as follows: cardiovascular (coronary artery obstruction, hypertension, transient ischemic attack, etc.) in 26 cases (31%), diabetes mellitus without diabetic retinopathy in 8 cases (10%), and autoimmune disorders in 6 cases (7%). The baseline demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Clinical Features

| Features | Value |

| Eyes (patients) | 83 (62) |

| Male gender, no. (%) | 73 (88) |

| Age at CSC diagnosis in years, mean ± SD | 54 ± 12 |

| Age at PCRD presentation in years, mean ± SD | 59 ± 10 |

| Caucasian, no. (%) | 68 (82) |

| Recent steroid use, no. (%) | 20 (24) |

| BCVA at diagnosis, in ETDRS letters, mean ± SD | 68 ± 19* (20/40 in Snellen equivalent) |

| Time from CSC diagnosis until PCRD presentation in months (range) | 61 (0–347) |

| Mean follow-up duration form CSC diagnosis in months (range) | 95 (4–373) |

Two patients (2 eyes) could only recognize hand movements.

ETDRS, Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study.

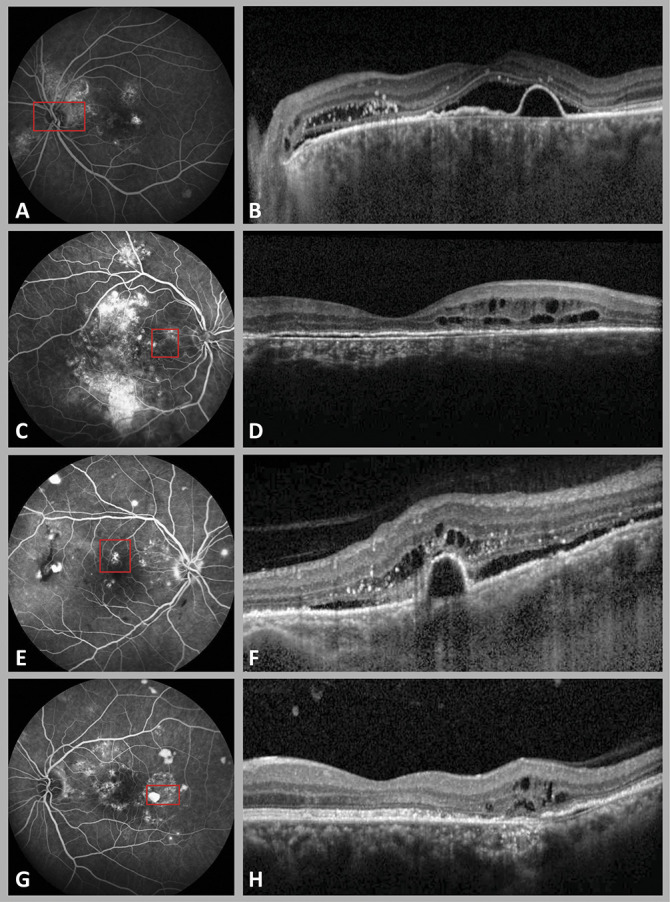

Characteristics on Optical Coherence Tomography Imaging

In 63 eyes (76%), active SRF leakage was present on OCT at first PCRD manifestation (Table 2). In 45 eyes (54%), PCRD was overlying a dome-shaped (15 eyes, 18%) or a flat irregular RPE detachment (30 eyes, 36%) (Table 2). In most cases, PCRD was present in the peripapillary region (32 eyes, 39%) or in the papillomacular region (35 eyes, 30%), whereas the fovea was involved in 15 eyes (18%). Eleven eyes (13%) showed PCRD outside these regions and without foveal involvement (Figure 1). Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration could be localized in the inner nuclear layer of the retina, the outer nuclear layer, the ganglion cell layer, but was most frequently observed to be present in multiple layers as summarized in Table 2. In 24 eyes (29%), large cystoid changes were observed that penetrated multiple retinal layers (Figure 2, F and H).

Table 2.

Findings on Multimodal Imaging in Patients With cCSC and Secondary PCRD Manifestation

| Imaging | Features | No. of Eyes (%/SD) |

| OCT at first PCRD manifestation | SRF | |

| Subfoveal | 52 (63) | |

| Peripheral | 11 (13) | |

| No SRF | 20 (24) | |

| PCRD association with PD | ||

| Dome-shaped | 15 (18) | |

| Irregular flat | 30 (36) | |

| No PD association | 38 (46) | |

| PCRD location in posterior pole | ||

| Peripapillary region | 32 (39) | |

| Papillomacular region | 35 (30) | |

| Foveal | 15 (18) | |

| Other* | 11 (13) | |

| PCRD location in retinal layers† | ||

| ONL | 16 (19) | |

| INL, ONL | 61 (74) | |

| INL, OPL, ONL | 5 (6) | |

| GCL, INL, ONL | 1 (1) | |

| OCT at final visit | SRF | |

| Subfoveal | 9 (11) | |

| Peripheral | 6 (7) | |

| Complete resolution | 68 (82) | |

| Presence of PCRD | ||

| Complete resolution | 31 (37) | |

| Reduced | 17 (21) | |

| Increased | 5 (6) | |

| Unchanged | 30 (36) | |

| FA after PCRD manifestation | Fluorescein leakage | |

| Focal | 29 (35) | |

| Diffuse | 36 (43) | |

| No leakage | 18 (22) | |

| Leakage associated with PCRD | 50 (60) | |

| Area of RPE atrophy in DD | 7.1 (SD = 4) | |

| RPE atrophy associated with PCRD | 69 (83) |

Other PCRD locations without foveal involvement included: five eyes (6%) temporal and nasal to fovea, three eyes (4%) temporal to fovea, two eyes (2%) inferior to fovea, one eye (1%) in papillomacular region and temporal to fovea.

The cystoid changes were larger and more prominent in the ONL in 70 eyes (84%), in 9 eyes (11%) in the INL, and in four eyes (5%) cystoid changes were equally prominent in the INL and ONL.

DD, optic disc diameter; ETDRS, early treatment diabetic retinopathy study; GCL, ganglion cell layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; and PD, RPE detachment.

Fig. 1.

Fluorescein angiography (A, C, E, G) and OCT (B, D, F, H) imaging in 4 cases of cCSC with secondary PCRD. Figure depicts four locations of PCRD lesions in posterior pole, including the peripapillary region (A and B), the papillomacular region without peripapillary or foveal involvement (C and D), the foveal region (E and F), and outside papillomacular intersection, in this case temporal to the fovea (G and H). The red square in each FA imaging illustrates the distribution area of cystoid lesions. The cystoid lesions were most prominently located in the outer nuclear layer (ONL) (B and F) of the retina, and to a lesser degree also in the inner nuclear layer (INL) (D and H).

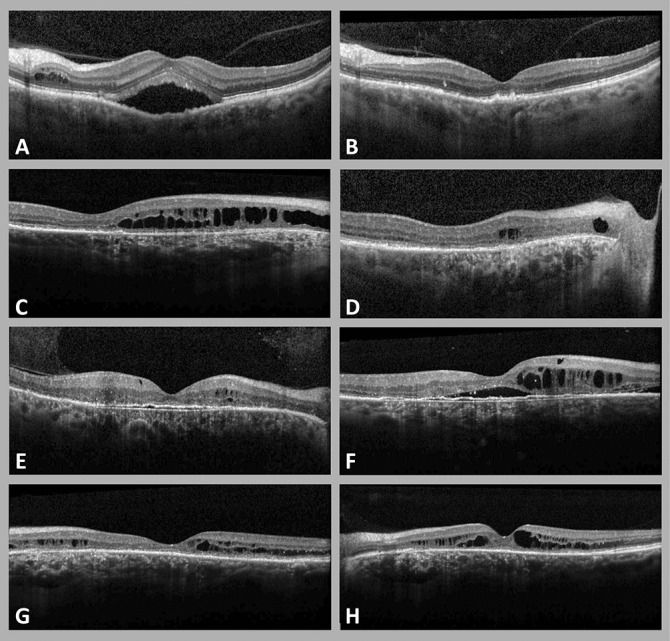

Fig. 2.

Optical coherence tomography imaging showing variable treatment response in 4 cases of cCSC with secondary PCRD (A–H). Four patterns of PCRD progression are illustrated during follow-up and until the final available visit. Complete resolution of PCRD and SRF occurred in the left eye of a 62-year-old male patient, after one treatment with half-dose PDT (A and B). Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration at final visit had decreased, but not resolved in the right eye of a 67-year-old male patient, who was treated with 3 half-dose PDT sessions and 2 intravitreal injections of bevacizumab (C and D). In a 62-year-old male patient (E and F), PCRD showed an increase in volume in the right eye, despite multiple treatments (three PDT treatments, one focal thermal laser, one subthreshold micropulse diode laser). The macula of a 42-year-old man, who was treated with focal thermal laser and three PDT treatments showed fluctuations of PCRD without a clear response to treatment (G and H).

At final available visit, on average 35 ± 29 months after the first PCRD manifestation, PCRD had completely resolved in 31 eyes (37%). Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration was reduced in 17 eyes (21%), remained unchanged in 30 eyes (36%), and showed an increase in 5 eyes (6%) compared with baseline. Subretinal fluid in this cohort had resolved completely in 68 eyes (82%) at final visit.

Characteristics on Fluorescein Angiography Imaging

The first FA imaging after PCRD manifestation showed active (multi)focal fluorescein leakage in 29 eyes (35%) (on average: 2.4 focal “hot spots” of leakage, range: 1–7 “hot spots”), whereas 36 eyes (43%) showed more diffuse leakage, attributed to SRF. In 18 eyes (22%), there was no fluorescein leakage (Table 2). In 50 eyes (60%), the area of leakage was associated with the location of PCRD. The mean cumulative area of DARA on FA was 7.1 DD (range: 0–20 DD), and in 69 eyes (83%) DARA included the location of PCRD (Table 2).

Treatment Outcome and Posterior Cystoid Retinal Degeneration Resolution

Among all eyes included in this study, 27 eyes (32%) had previous treatment for cCSC before PCRD manifestation, whereas 56 eyes (68%) were treatment-naive (see Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/IAE/B129). Sixty-seven study eyes (81%) were treated after PCRD manifestation, of which 21 eyes (21/67, 31%) had previously received treatment before PCRD manifestation. Of a total of 67 treated eyes, 36 eyes (54%) had a complete resolution of PCRD. Complete resolution occurred after a single treatment in 27 eyes (33%) (of which PDT in 25 eyes, 30%), and after multiple treatments in 7 eyes (9%). In 2 eyes (2%), PCRD resolved independent of treatment (Figure 2, see Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/IAE/B129, and see Table 3, Supplemental Digital Content 3, http://links.lww.com/IAE/B130). Among cases with foveal involvement of PCRD that were treated (14/67, 21%), eight eyes (8/14, 57%) had a complete PCRD resolution. Forty-nine study eyes (49/67, 73%) had received PDT as first treatment option, among which 23 eyes (23/49, 47%) showed a complete resolution of PCRD after this first PDT. Recurrence of PCRD was observed in four eyes (4/23, 17%) with an initial PCRD resolution after first successful PDT treatment.

Best-Corrected Visual Acuity Outcome

The mean baseline BCVA in the entire group was 69 ± 19 ETDRS letters (20/40 in Snellen equivalent), reducing slightly to 67 ± 20 ETDRS letter (20/50 in Snellen equivalent) at final visit (P = 0.354). Final BCVA outcome did not differ significantly among eyes with and without PCRD resolution (64 ± 23 and 67 ± 20 ETDRS letters respectively [20/50 and 20/40 in Snellen equivalent respectively], P = 0.499). The follow-up duration after PCRD manifestation was comparable in eyes with and without complete PCRD resolution (36 ± 32 and 32 ± 23 months respectively, P = 0.515). Best-corrected visual acuity improvement after a complete PCRD resolution was variable depending on the location of PCRD (see Table 4, Supplemental Digital Content 4, http://links.lww.com/IAE/B131).

Factors Influencing Posterior Cystoid Retinal Degeneration Resolution

Univariate COX regression analysis indicated that presence of SRF as a sign of active leakage at first PCRD manifestation (HR = 4.09, CI = 1.23–13.54, P = 0.021), and older age at initial cCSC diagnosis (HR = 1.05, CI = 1.02–1.09, P = 0.004), increased the probability (hazard) of PCRD resolution. However, a larger surface of DARA (HR = 0.86, CI = 0.77–0.96, P = 0.005) decreased the probability (hazard) of PCRD resolution (Table 3). After performing a multivariate analysis of HRs, SRF leakage at first PCRD manifestation (HR = 2.47, CI = 0.65–9.45, P = 0.186), and the size of DARA surface (HR = 0.90, CI = 0.81–1.01, P = 0.065), although still indicative, lost statistical significance as predictive factors for PCRD resolution. Older age at initial cCSC diagnosis (HR = 1.05, CI = 1.01–1.09, P = 0.025) remained a statistically significant predictor (Table 3).

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios of Factors Predicting Complete Resolution of PCRD in cCSC Patients

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis* | Multivariate analysis* | ||

| HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P | |

| Male gender | 1.02 (0.36–2.86) | 0.967 | 1.16 (0.36–3.71) | 0.807 |

| Caucasian ethnicity | 1.60 (0.70–3.65) | 0.262 | 0.39 (0.14–1.07) | 0.068 |

| Steroid use | 1.08 (0.47–2.52) | 0.852 | 0.64 (0.22–1.88) | 0.420 |

| SRF leakage at PCRD manifestation | 4.09 (1.23–13.54) | 0.021 | 2.47 (0.65–9.45) | 0.186 |

| SRF leakage under PCRD | 0.46 (0.62–2.83) | 0.464 | 1.35 (0.52–3.56) | 0.540 |

| Foveal location of PCRD | 2.24 (0.98–5.12) | 0.055 | 1.78 (0.73–4.32) | 0.205 |

| DARA surface | 0.86 (0.77–0.96) | 0.005 | 0.90 (0.81–1.01) | 0.065 |

| Age at cCSC diagnosis | 1.05 (1.02–1.09) | 0.004 | 1.05 (1.01–1.09) | 0.025 |

The overall model was statistically significant with a Chi-square P-value of 0.003.

DARA, diffuse atrophic RPE alteration.

Discussion

Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration is a common feature in patients with advanced cCSC and can be viewed upon as a sign of more severe disease.6,9 In the present study, most PCRD cases also showed active leakage on FA, serous neurosensory detachment, and associated RPE atrophy. Although treatment led to a complete resolution of SRF in 82% of the cases, less than half of the cases showed resolution of PCRD. Interestingly, the probability (hazard) of PCRD resolution was most strongly associated with coexistence of active SRF leakage. Best-corrected visual acuity outcome was relatively poor as compared to uncomplicated cCSC and did not change during follow-up, even in cases with PCRD resolution.

The pathogenesis of PCRD is unclear. A complex hemostatic equilibrium maintains a dehydrated state, and thereby the transparency and functionality of the retina.16 An imbalance in fluid entry and/or drainage can therefore lead to retinal edema.16 Although the inner blood–retinal barrier prevents serum passage by the act of the intercellular junctions of the endothelial cells and transendothelial transport, the outer-retinal barrier regulates fluid drainage through the intercellular tight junction complex of the RPE cells and the external limiting membrane.16–18 Dysfunctionality of these natural barriers contributes to an increased fluid entry in the retina or subretinal space. Leukostasis, which may arise as a result of local ischemia or an inflammatory process, was suggested as a possible cause of reduced capillary flow in the deep retinal plexus in the sites of retinal edema.17 This may in turn prevent a normal fluid drainage by the deep capillary plexus.17 Furthermore, an impairment in the natural pumping function of the RPE cells and the Müller cells is suggested to contribute to insufficient fluid drainage, and subsequent subretinal and intraretinal fluid accumulation.16,17,19 This loss of pumping function may occur through structural cell damage, cell disorganization, and cell death by atrophy.19 All these factors contribute to the appearance of cystoid macular edema. Cystoid maculopathy is most frequently associated with retinal vasculopathies.20 However, cystoid maculopathies may also occur in diseases originating in the choroid, such as chronic CSC.20,21 The mechanism of PCRD in cCSC may be predominantly related to outer blood–retinal barrier breakdown and decreased active fluid drainage, which are both the result of a dysfunctional RPE layer.21,22 Our observations in the present study support this theory, as presence of DARA directly underneath PCRD was observed in 83% of our cases. Previous studies on cCSC-associated PCRD also reported that the largest cystoid spaces were often close to the atrophic RPE lesions.10,12

Spontaneous resolution of PCRD in our cohort was rare, and treatment was therefore often used. Currently, no standard treatment exists for cCSC-associated PCRD, and small case series have reported inconsistent results.11–13,21 Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration in our cohort was accompanied by active SRF leakage in most cases, and 81% of these eyes received treatment. A large variety in treatment strategies and treatment frequency was used in the present study. Therefore, evaluating treatment efficacy in PCRD cases was challenging. Nevertheless, 54% of the cases showed a complete resolution of PCRD, often after a single PDT treatment with reduced settings for the presence of SRF. Overall, PDT was the most frequently used treatment with the relatively highest rate of complete PCRD resolution after treatment (39%) compared with the other used treatments. This rate of complete PCRD resolution after PDT is relatively high in comparison to previous smaller studies on PCRD.14,23 Still, the success rate for PDT on resolution of PCRD fluid, which is located intraretinally, is considerably lower than the reported success rates of 67 to 100% in resolving SRF in cCSC.23–26 Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration thus seems to be more therapy-resistant than SRF in cCSC. Also, BCVA in our PCRD cases showed no overall changes during follow-up even after PCRD resolution, presumably because of irreversible retinal cell loss. Treatment of cCSC before the occurrence of PCRD may therefore be advisable.

We showed that cases with active SRF leakage in conjunction with PCRD manifestation had a higher probability of PCRD resolution after treatment (often PDT). This indicates that PCRD is at least partly dependent on the underlying active choroidal/RPE leakage process, and therefore may resolve well when this process becomes more quiescent after treatment. The group of PCRD without SRF leakage was less likely to show resolution after treatment, indicating that this subgroup is less dependent on underlying choroidal/RPE leakage and more degenerative in nature. These observations suggest that the mechanism in PCRD manifestation consists of a variable contribution of two components: 1) a homeostatic fluid imbalance component, leading to intraretinal fluid (PCRD) and SRF. This component seems more likely to respond to (PDT) treatment. 2) a degenerative component, leading to tissue loss and intraretinal cystoid cavity formation. This component is less likely to respond to treatment. A degenerative loss of tissue, especially loss of Müller cells, has been previously suggested in the occurrence of macular edema.19 Müller cells may die presumably because of intracytoplasmic edema, and leave a cystoid space behind.19 A similar process may explain the degenerative component of PCRD in our study.

In the current study PCRD was located peripapillary in more than a third of patients. This pattern of extra-foveal localization, which was also observed in previous studies,10,12 may distinguish PCRD from macular edema in the context of other retinal vasculature abnormalities.20 The recently described clinical picture of peripapillary pachychoroid syndrome (PPS), which like PCRD is also characterized by peripapillary intraretinal cystoid changes in association with hyperpermeable choroidal vessels, shares many features that we also observed within the spectrum of cCSC with PCRD.12 Subretinal fluid leakage for instance, was frequently observed in both PPS cases (74%) and in our cohort (76%).12 Atrophic RPE associated with cystoid changes were observed in 100% of PPS cases,12 whereas PCRD-associated DARA was present in 83% of our cases. Because of the similarities, PPS may be regarded as a peripapillary form of cCSC with PCRD. However, unlike PPS cases, BCVA outcome in our PCRD cases was poor, and showed no overall changes during follow-up even after PCRD resolution. This lack of reversible visual acuity is another characteristic of PCRD in comparison with other forms of retinal edema or PPS, where BCVA may improve more significantly once edema is resolved.11,12

In this study, some of our observations may have been subject to bias because of the retrospective study design and limitations in availability of certain data. For instance, the follow-up duration and treatment regimens were variable. Also, no suitable control group was available to compare treatment outcome (especially after PDT treatment) in cCSC cases with and without PCRD manifestation. Nevertheless, important conclusions can still be drawn. Our study suggests that PCRD in cCSC is a sign of retinal cell loss, because treatment was less successful in resolving PCRD compared with SRF resolution, and because final BCVA outcome remained poor. Further studies are needed to assess whether earlier treatment of cCSC may prevent the development of PCRD and the associated irreversible vision loss, and to assess the best treatment options for PCRD.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the following funding sources: Stichting Leids Oogheelkundig Ondersteuningsfonds, Rotterdamse Stichting Blindenbelangen, Stichting Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek Het Oogziekenhuis, Macula Fonds, Landelijke Stichting voor Blinden en Slechtzienden, Retina Netherlands, and BlindenPenning. C. J. F. Boon was supported by a Gisela Thier Fellowship from Leiden University and a ZonMw VENI grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). These sponsors and funding organizations played no role in the design or conduct of this research.

None of the authors has any financial/conflicting interests to disclose.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.retinajournal.com).

S. Yzer and C. J. F. Boon are shared last authors.

References

- 1.Daruich A, Matet A, Dirani A, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy: recent findings and new physiopathology hypothesis. Prog Retin Eye Res 2015;48:82–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loo RH, Scott IU, Flynn HW, et al. Factors associated with reduced visual acuity during long-term follow-up of patients with idiopathic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 2002;22:19–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breukink MB, Dingemans AJ, den Hollander AI, et al. Chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: long-term follow-up and vision-related quality of life. Clin Ophthalmol 2017;11:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang M, Munch IC, Hasler PW, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol 2008;86:126–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spaide RF, Campeas L, Haas A, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy in younger and older adults. Ophthalmology 1996;103:2070–2079; discussion 9–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohabati D, van Rijssen TJ, van Dijk EH, et al. Clinical characteristics and long-term visual outcome of severe phenotypes of chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Clin Ophthalmol 2018;12:1061–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otsuka S, Ohba N, Nakao K. A long-term follow-up study of severe variant of central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 2002;22:25–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castro-Correia J, Coutinho MF, Rosas V, Maia J. Long-term follow-up of central serous retinopathy in 150 patients. Doc Ophthalmol 1992;81:379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iida T, Yannuzzi LA, Spaide RF, et al. Cystoid macular degeneration in chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 2003;23:1–7; quiz 137–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccolino FC, De La Longrais RR, Manea M, Cicinelli S. Posterior cystoid retinal degeneration in central serous chorioretinopathy. Retina 2008;28:1008–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staurenghi G, Lai TYY, Mitchell P, et al. Efficacy and safety of ranibizumab 0.5 mg for the treatment of macular edema resulting from uncommon causes: twelve-month findings from PROMETHEUS. Ophthalmology 2018;125:850–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phasukkijwatana N, Freund KB, Dolz-Marco R, et al. Peripapillary pachychoroid syndrome. Retina 2018;38:1652–1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patron ME, Vuong LN, Duker JS. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide for cystoid macular edema secondary to central serous chorioretinopathy. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2009;3:319–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Do JL, Olmos de Koo LC, Ameri H. Atypical chronic central serous chorioretinopathy with cystoid macular edema: therapeutic response to medical and laser therapy. J Curr Ophthalmol 2017;29:133–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gregori NZ, Feuer W, Rosenfeld PJ. Novel method for analyzing snellen visual acuity measurements. Retina 2010;30:1046–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daruich A, Matet A, Moulin A, et al. Mechanisms of macular edema: beyond the surface. Prog Retin Eye Res 2018;63:20–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spaide RF. Retinal vascular cystoid macular edema: review and new theory. Retina 2016;36:1823–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bringmann A, Reichenbach A, Wiedemann P. Pathomechanisms of cystoid macular edema. Ophthalmic Res 2004;36:241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanoff M, Fine BS, Brucker AJ, Eagle RC., Jr Pathology of human cystoid macular edema. Surv Ophthalmol 1984;28(suppl):505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaudric A. Macular cysts, holes and cavitations. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2008;246:1071–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Astroz P, Balaratnasingam C, Yannuzzi LA. Cystoid macular edema and cystoid macular degeneration as a result of multiple pathogenic factors in the setting of central serous chorioretinopathy. Retin Cases Brief Rep 2017;11(suppl 1):S197–S201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schatz H, Osterloh MD, McDonald HR, Johnson RN. Development of retinal vascular leakage and cystoid macular oedema secondary to central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 1993;77:744–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Dijk EHC, Fauser S, Breukink MB, et al. Half-dose photodynamic therapy versus high-density subthreshold micropulse laser treatment in patients with chronic central serous chorioretinopathy: the PLACE trial. Ophthalmology 2018;125:1547–1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lim JI, Glassman AR, Aiello LP, et al. Collaborative retrospective macula society study of photodynamic therapy for chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1073–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tseng CC, Chen SN. Long-term efficacy of half-dose photodynamic therapy on chronic central serous chorioretinopathy. Br J Ophthalmol 2015;99:1070–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rijssen TJ, van Dijk EHC, Ohno-Matsui K, et al. Central serous chorioretinopathy: towards an evidence-based treatment guideline. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2019; S1350-9462(18)30094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.