Abstract

Currently cellphone fraudsters often use language to threaten and bully victims. From discursive psychological perspective, the present study applies conversation analysis to discuss fraudsters’ threatening language in Chinese cellphone fraud conversations. The authentic data are collected from Chinese media which report legal news or conduct public legal education on the battle against cellphone frauds. Results of the study show that: (1) cellphone fraudsters construct their false identities through information gap and information sharing in their turn-taking designs, which brings victims into the threatening fraud interactions; (2) fraudsters use such conversational skills in a threatening tone as repetition, interruption, higher pitch, louder speech and so on to trigger victims’ psychological panic; (3) fraudsters’ discursive practices are situated for the threatening actions based on prepared and designed scripts. The findings of the study are expected to provide references for preventing cellphone fraud and fighting against fraudsters’ threats and bullies.

Keywords: Threatening language, Discursive psychology, Conversation analysis, Cellphone fraud

Introduction

Currently, telecom fraud has become an increasingly serious crime, which “affects social stability and the sense of security of the public” [49]. For the purpose of possessing other people’s property illegally, criminals fabricate false discourse and set up scams through landline phone, cellphone or other Internet communication tools to commit remote frauds against victims, seriously infringing on the people’s legitimate rights and interests.

The scientific research on telecom frauds has achieved a lot since the end of last century. On the one hand, the early research achievements on telecom fraud was mainly as follows, the introduction to telecom fraud [32], the categorization of telecom fraud [9–11], causes and consequences of telecom fraud [23], suitability of relevant laws and regulations [1], and the technological development in banks and telecommunications companies for the prevention on telecom fraud [12]. On the other hand, with the development of internet and online communication, the research is increasingly focused on the novelty of telecom fraud, such as the approaches to the computer-aided identification of telecom frauds [42], the improvement of relevant laws to promote the establishment of law enforcement system and administrative supervision system to prevent and combat telecom fraud [47], the joint investigation and control mechanism among banks, judicial bodies and telecommunications companies [45], the mechanism of international cooperation on the prevention and punishment and the judicial assistance mechanism [24].

Till now, the linguistic research on telecom fraud focuses remarkably on email frauds. Chiluwa [8] has made a computer-mediated analysis of discourse structures and functions of emails, which reveals that the email writers apply discourse/pragmatic strategies such as socio-cultural greeting formulas, self-identification, reassurance/confidence building, narrativity and action prompting strategies to sustain the receivers’ interest. Freiermuth [18] has analyzed the scammers’ intention behind each rhetorical move that exists in email messages. Onyebadi and Park [33] have examined the framing of email communications used in the frauds, with the findings indicating that the scammers used Realism as the main persuasive lexical characteristic in the messages.

However, much more importance needs to be attached to the research on cellphone fraud discourse. Firstly, a great number of telecom frauds are implemented through cellphone interactions and false discourse information is always transmitted via cellphones in those crimes [27]. In the fraud interactions, language use has much deeper influence on fraudsters’ identity construction [50] and language interpretation produces a certain social identity in communications [31]. Thus, it is necessary to explore how cellphone fraudsters shape their false identities through their language use and victims’ language interpretation. Secondly, there are two major means of cellphone frauds, one is seductive deception and the other is threatening deception. It is emphasized that the process of “seduction” and “deception” cannot do without activities of speech communication [50], but the process of “threatening” and “deception”, especially threats constructed through discursive strategies in cellphone frauds, has not been touched in any studies. Thirdly, since asymmetrical roles or unequal positions exist between fraudsters and victims in telecom fraud interactions [49], it is needed to investigate the roles fraudsters’ threatening language plays in the distribution of power and control.

Threat, from a social perspective, focuses extensively on speakers’ communicative intentions to frighten victims and influence their behaviors [7]. Threat in some research has been regarded as a speech act performed in threatening discourse [40, 44]. Special attention has always been paid to direct threats and indirect ones [17, 20], in which required conditions have been provided for defining the speech act of making a threat [44]. However, there is still no clear-cut between direct and indirect threats. Instead of the binary contrasts, Muschalik [30] has therefore proposed a scalar approach to illustrate the degree of different threats, which offers the possibility to do quantitative linguistic study of threat. From the interpersonal angle, Gales [19] has revealed threateners’ convey of interpersonal meanings through rhetorical strategies and their stance-taking in threatening discourse. All the previous studies have provided references for the macro-analysis of threatening language in fraud interactions. Other studies concentrate on semantic meanings of threats [21, 48] or word choices [30]. The former research offers “the basic structure of the threats uses a conditional logic: if the recipient continues problem action/does not initiate required action then negative consequences will be produced by the speaker.” [21], which is consistent with Sacks’ [39] discussion on warning/threat as an initiating action in an adjacency pair. The latter categorizes the verbs used for threats into violent, ambiguous or non-violent, with four sub-types of violent verbs [30]. These studies demonstrate that threatening language can be investigated from lexical, syntactic and semantic aspects.

In spite of the above-mentioned research on threats or the language used for making threats, the threatening language in cellphone fraud interactions has been touched in very few empirical studies so far. Taking the specific contexts in cellphone frauds into consideration, the meanings of threats may be constructed in different ways, which is of significance to explore from the linguistic aspect.

In accordance with the literatures above, threatening language, as the working definition here, can be defined in such a broad sense as the discourse, utterance or speech used by speakers to perform direct or indirect threats to and impose psychological pressure on listeners for achieving certain communicative objectives. Threat can be defined that an action, detrimental to listeners, is constructed or performed through language used by speakers. For the purpose of more convenient distinction in the present study, victims’ fully exposure to the threatening or bullying languages will be discussed as direct threat while indirect ones are constituted in implicitly stated threatening or bullying languages that still exert much pressure over victims. In cellphone frauds, threatening language is used by fraudsters in the fraud interactions, which constructs threat to victims and bring the victims with huge psychological pressure into the cellphone traps.

Therefore, the present paper presents a discursive psychological analysis of Chinese cellphone fraud interactions, focusing on the ways in which fraudsters use threatening language to help carry out remote frauds.

Discursive Psychology and Conversation Analysis

Discursive Psychology: Theoretical Basis

Discursive psychology (DP), different from traditional psychology that separate mental activities from external behaviors, is a perspective for studying discourse as social practice, with mental activities and external behaviors integrated [28]. The three core principles of DP are: discourse is both constructed and constructive, discourse is situated within a social context, and discourse is action-orientated [16, 46].

DP treats language, with cellphone fraudsters’ discourse no exception, as constructed and constructive. DP takes a relativist, social constructionist stance to knowledge [46]. To say that cellphone fraudsters’ discourse is constructed, it is necessary to analyze the way fraudsters speak to the victims and to explore how particular aspects of frauds as event are constructed and whether the fraud effects in cellphone interactions are achieved. Discourse is simultaneously constructive of a particular version of reality through the choice of “particular words formulations over others” [41] or “of different versions of the world, through the way in which we talk about people, events, actions and organizations ([46]: 10)”. Thus, DP can be employed to examine how fraudsters create false realities or build their certain false identities by their language use as a policeman, a bank clerk, or a gang member, and so on to threaten and entrap victims.

In DP, discourse is situated within a social context in that DP is a theoretical and analytical approach that treats talk and text as social action rather than representation, and talk and text are argued to accomplish actions in the social world [46]. That is, discourse is action-oriented in an interactional context and the action orientation of language highlights how people use language to do things and to reach their certain purposes [4] or to get things done [35]. An example is a piece of cellphone talk between a fraudster and a victim, in which the fraudster’s discourse performs an action as defrauding in the interaction. The fraudster’s statement “Your son is with me.” To respond with the question “What’s your ransom demand?”, the victim treats it as his son being kidnapped. The fraudster’s statement relates to the performative nature of language, i.e. he does things with language [16].

A discursive psychological approach is also ethnomethodologically-oriented [15]. Firstly, DP was developed within psychology but is influenced by linguistics, philosophy, sociology, post-structuralism, ethnomethodology and conversation analysis (CA), in which psychology as an object to be analyzed for how it is made consequential in social interaction [46]. “Discursive psychologists examine the performative qualities of descriptions as part of action sequences in real life talk. This interest can be traced back directly to the influence of conversation analysts. Conversation-analytic studies demonstrate that what people do with language” ([29]: 2). Secondly, turns at talk in specific cellphone fraud contexts are to be understood by both fraudsters and victims within the sequence organizations, and “we can examine the situatedness of the talk in terms of the turn-by-turn interaction. ([46]: 13)” Therefore, it is essential to investigate how fraudsters treat their turn-taking by applying the “next-turn proof procedure” ([25]: 15). Thirdly, DP research is mostly concerned with how such psychological concepts as desires or fears that underpin conversations and interactions, in various particular settings [15]. It is corresponding to the idea that ethnomethodology “aims to understand the methods, through which people make sense of each other’s practices in everyday settings: how people make sense of what they are doing. ([46]: 243)”

In addition, since online spoken interaction as a form of talk in its own right needs much more attention [29], DP has also been employed to study online discourse as a social practice [41]. Accordingly, DP offers a new methodological path in this study, for the exploration of cellphone fraud interactions, one form of online interactions.

Conversation Analysis: Analytical Tool

CA is an approach to analyzing natural discourse that examines sequential organizations and action-orientation of talk-in-interaction [46]. More specifically speaking, CA is concerned with every social conduct or action in various natural communication contexts [34].

Historically, since its derivation from ethnomethodology and sociolinguistics, CA has been closer to DP in approach and regarded ethnomethodologically the sociology as a theoretical or methodological resource [35]. CA conventions have recently and increasingly been used for discursive psychological study of the natural interactions recorded and transcribed.

Theoretically, CA focuses on the structures and organizations of talk and on how social actions are constructed through the careful language use. It is commonly known that CA starts with “talk in interaction”. CA attends “to understand the mechanics of interaction ([46]: 36)” and “the ways in which participants’ talk is oriented to the practical concerns of social interaction [3]”, such as how a conversation begins, how assessments are made, and how refusals or offers are completed, and “how descriptions, accounts, and categories in conversation are put together to perform specific actions [3].” For example, since threats in adjacency pairs have largely been ignored in the conversation analytic literature for many years [21], it is can be examined that fraudsters attend to their fraudulent gains and accountability in threatening fraud interactions.

Methodologically, CA provides a useful analytical tool for DP. Turn-taking systems, sequence organizations, overall structural organization of the interaction, lexical choice, and so on have been identified as important domains of interactional phenomena [13, 22]. Firstly, as the fundamental units, turns are designed carefully or carelessly, intentionally or unintentionally in the sequence organizations. Repetition, interruption, self-corrections, pause within a turn, and overlapping parts between turns are often analyzed in social interaction. Secondly, lexical choice is also important in the language use for the action achievements. Thirdly, it is typical in CA that suprasegmental elements and details in transcripts such as length of pauses, prolonged syllables, pitches, loudness and some other prosodic features have been widely accepted to be relevant parameters for conversation [3, 37] in that the information is conveyed about speakers’ emotional states or “attitude toward the topic under discussion ([26]: 26)”.

“DP draws on many of the tools of CA, including focusing on turn-taking and sequential organization, but rather than starting with social actions, DP focuses first on a specific psychological issue or the production of categories in talk. ([46]: 44)” Here, CA is employed as a useful analytical tool for the study of some cellphone fraud interactions, starting with fraudsters’ and victims’ different mental states.

Methodology

Data Collection

In this paper, 20 pieces of cellphone conversations in the authentic fraud cases are collected from Chinese media. To protect privacy, the police and telecommunications companies have just provided parts of those cellphone call recordings. The media have only released some typical audio clips for legal news reports or public legal education on the fight against telecom frauds, the mainstream news media including CCTV (China Central Television), Chinanews, Tencent, Sohu, Sina and so on. In these clips, there are 6340 seconds for fraudster-victim’s conversation and 750 seconds for the police’s and reporters’ comments. Specifically speaking, the legal opinions on these cases have been included in the videos or audios, or in the corresponding hypertexts, warning people not to fall into the cellphone fraud or conducting legal education. The links of the videos or audios, and the corresponding news titles or hypertexts are listed in “Appendix 2” for the convenience of searching.

To ensure validity and reliability, two raters have firstly confirmed fraudsters’ threatening language in the authentic cellphone frauds. When the results do not match, the discrepancy has been resolved through negotiation. Secondly, the typical cases have been categorized to figure out fraudsters’ false identities as policemen in 14 cases, procurator, telecom staff or gang leader in other 6 cases respectively. Thirdly, direct or indirect threats in the data have been classified and different conversation skills used in the threatening language are counted. Fourthly, threat clauses have been segmented with Praat 6.1.13 [6], and the numbers of repetitions, interruptions and syllables with supersegmented features are also counted. At last, in these cases, some victims have been cheated and even transferred money to the fraudsters, others have recognized the frauds or been successfully stopped by the police from transferring their money. We have extracted and analyzed some pieces of the conversations between the fraudsters and the victims, in which their names or nicknames have been anonymized and the ID numbers or phone numbers involved have been omitted partially for privacy protection.

Research Questions

The main aim of DP is to examine how psychological constructs are enacted and made relevant in interaction and the implications of these for social practices, while that of CA is to examine social actions and the sequential and organizational features of talk that accomplish these actions. Both DP and CA are predominantly used with video or audio recordings in social interactions. These issues could be tackled from a DP and CA perspective, specifically in relation to accountability and fact construction. For CA, the interaction itself needs “to be the focus of analysis”, and “provides a rich source of data” ([46]: 38) of fraudster–victim interaction.

Therefore, the present study aims to venture into cellphone fraud discourse by analyzing how fraudsters use language to construct the actions of threat and examining how they employ discursive strategies to accomplish these actions in the Chinese cellphone fraud interactions. Based on the three fundamental principles of DP, i.e. discourse is constructed constructive, action-oriented, and situated, three questions will be answered in the present study:

How are fraudsters’ false identities constructed in the threatening fraud interactions?

What conversational skills are used by fraudsters to trigger victims’ psychological panic?

How are fraudsters’ discursive practices situated to account for the threatening actions?

Data Analysis

DP is drawn upon to conduct a data-based qualitative analysis of the interactional features [41] of natural fraudster-victim talks. On the one hand, some extracts are taken as examples for discourse analysis to demonstrate fraudsters’ false identity construction, conversational skills and discursive situations. On the other hand, we will make statistical analysis of fraudsters’ different conversational skills used in specific situations. Data analysis starts with data transcript and data coding based on CA conventions (see “Appendix 1”). To answer the first question, we will explicate the way in which fraudsters bring victims into discursive sequence and psychological interactions through turn-taking design. For the second question, we will analyze the conversational features in fraudsters’ threatening language such as stress, loudness, tempo, interruption and repetition. And the third question will be answered in the discussion of fraudsters’ discursive practices at both micro-level and macro-level.

Fraudsters’ False Identities Constructed in Cellphone Interactions

Discourse is constructed in the social interactions in that in a certain sequential order turn-taking promotes discourse development from inner-sentence and inter-sentence levels to global-discourse level [14]. Through turn-taking design, cellphone fraudsters bring victims into discursive sequences in threatening fraud interactions. The fact that discourse is constructed is embodied through the way in which fraudsters speak to victims and the fraud effects on victims.

Information Gaps in Sequence Organizations

As action is oriented, discourse is also constructive in the situated context. In the data, fraudsters’ turn-taking design often intentionally constructs false identities with threatening language and entrap their preys, resulting from information gaps between victims and them in the interactions. For example,

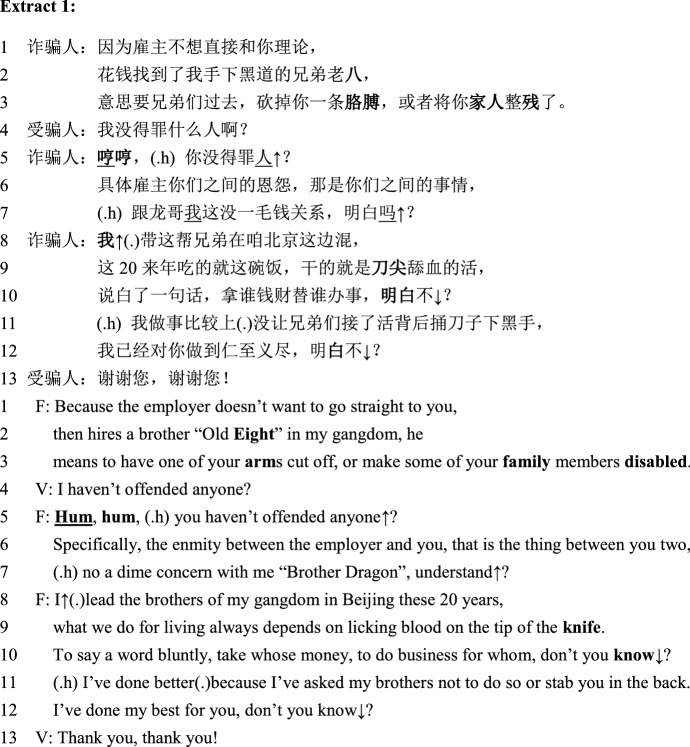

Case 07 is collected from CCTV News report on fraud with the title “遭遇匿名电话威胁 实为电信诈骗新招 (Threatened by an Anonymous Phone Call A New Way for Telecom Fraud)”. In Extract 1 of Case 07 (00:23-01:18),1 the fraudster constructs the fearful and frightening events through the new information from Lines 1–3 in the first turn, in which he chooses the scary words like “黑道 (gangdom)”, “砍掉 (cut off)” and “残 (disabled)” to make the direct threat in full function, i.e. a threatened future action detrimental to the victim [40]. However, the victim’s response “我没得罪什么人啊? (I haven’t offended anyone?)” shows that he is confused at the fraudster’s words because the information gap between them has been created. In order to achieve his purpose effectively, the fraudster then changes the turn to tell the victim intentionally and sequentially about his fictional experiences in Lines 8-10, using such a clause with the frightening meaning as “干的就是刀尖舔血的活 (what we do for living always depends on licking blood on the tip of the knife)”. It is the new information of an indirect threat that results in the victim’s nervousness, and even scare and panic. In the interaction, the information gap appears between the fraudster’s information surplus and the victim’s information vacancy [14]. The fraudster’s false identity has been constructed as a gang leader in the adjacency pair in Lines 12–13, in which the victim’s belief in the speaker’s ability to act and intention to act [17] can be proved by the victim’s “谢谢您,谢谢您! (Thank you, thank you!)”.

Fraudsters may often fabricate victims’ criminal evidence to create information gaps, i.e. one of victims’ bank cards involving financial crimes, so that the fictitious crime can get in touch with the bank card and pave the way for fraudsters to elicit victims’ bank card information, balances, passwords, verification codes and so on. In Case 05, the cellphone fraudsters were caught and brought from Indonesia to China by Shanghai Police, reported on “澎湃新闻 (The Paper)”. According to the report, those fraudsters have set a three-line cellphone working group in the whole fraud process. The phone team in the first line poses as “customer service”, such as bank staff, water or gas company clerk, to inform their victims that they have overdue bills, conclude that the victims’ identities have been illegally used, and then transfer the phone to the second line. In the second line fraudsters will play as “police” to inform the victims that they have been involved in some serious crimes, and the impersonated police then lead their victims to a third-line “prosecutor”. The false prosecutor guides the victims to deposit the money into an account designated by them to complete the fraud.

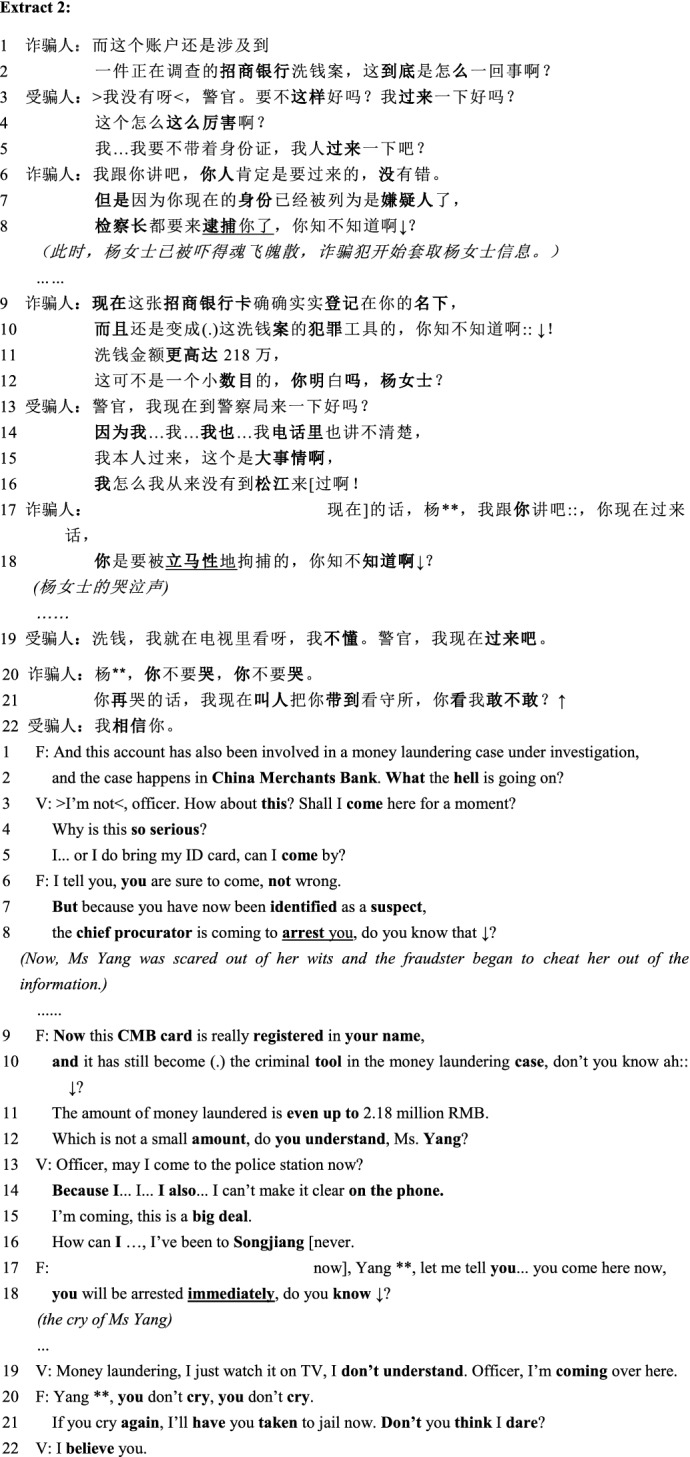

In Extract 2 of Case 05 (00:00–02:23), the fraudster takes money laundering as the main topic in the threatening discourse development. He constructs the turn that the victim’s bank card is involved in a money laundering case in Lines 1–2, and then interrogates the victim “这到底是怎么一回事啊? (What the hell is going on?)” in a policeman’s implicitly threatening voice. In that turn, the fraudster finishes two processes in turn-taking system, i.e. turn-construction component and turn-allocation component [38]. In the adjacency pair, the victim responds immediately to the fraudster’s turn allocation to deny her crime with a high-speed expression “>我没有呀 < (> I’m not <)” in Line 3. As a matter of fact, the new information about the so-called criminal case has frightened the victim and the information gap has brought her to the edge of the fraud trap because she has expressed her worry about the case and her willing to go to the police station in Lines 3–5. As the analysis shows, the victim’s response seems to be predicted by the fraudster as he has made both direct and indirect threats in Lines 6–8 to impose much more psychological pressure on the victim and even to control her entirely. For the one point, the fraudster uses the clause “你人肯定是要过来的 (you are sure to come)” to construct an indirect threat in the specific situation alongside the victim’s words; for the other reason, in the new turn the fraudster strengthens his false police identity as well as frightens the victim by the direct threat “…你现在的身份已经被列为嫌疑人了, 检察长都要来逮捕你了 (…you have now been identified as a suspect, the chief procurator is coming to arrest you)”.

After the success of eliciting the victim’s some information and exercising mental control over the victim, the fraudster changes to another turn in Lines 9–12 to reinforce the fact that the victim’s bank card is regarded as a money laundering tool under her name, with a large amount of money, i.e. 2.18 million RMB involved. However, the victim is still unwilling to give up her innocence in the next turn in Lines 13–16. The fraudster threatens the victim directly again by the four clauses in the following turn in Lines 17–18, which have resulted in the victim’s extreme panic and her cry on the phone. In accordance with the “well-prepared and elaborately-designed ‘phone script’” [49], the information gap between the fraudster and the victim has constructed the fraudster’s police identity successfully and tricked the victim’s discourse smoothly and sequentially into the fraudulent discourse development, which has been demonstrated by the victim’s “我相信你 (I believe you)” in Line 22.

Information Sharing in Sequence Organizations

Except for the false identity construction through information gaps, fraudsters can also invoke their false identities based on information sharing with victims in the specific sequences, in which much pressure is exerted on victims although threats are always made indirectly.

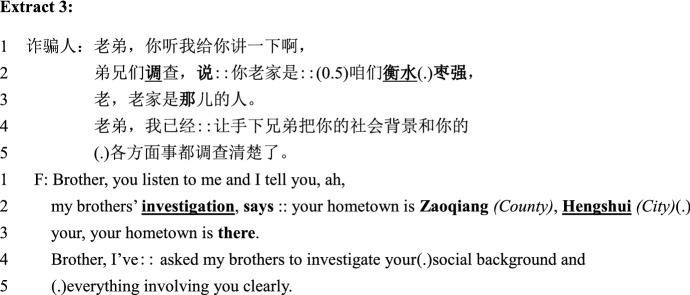

Fraudsters transmits victims’ personal information gathered illegally to victims, sharing the fact information with them. It is the first key step for a cellphone fraud sequence that fraudsters possess victims’ personal information and can speak out victims’ names, ID numbers and home addresses accurately on the phone. Consequently, the victims are easy to trust the fraudsters so that the fraudsters may succeed in their false identities constructed with the indirect threatening language. For example, Case 08 has been reported on CCTV 13 and been confirmed as a cellphone fraud case, in which the fraudster uses the prepared fraud scripts to play a role as a gang leader and pretends that he can order his gang members to do something harmful to his victims. In Extract 3 from Case 08 (00:24–00:42), the fraudster in Line 2 has spoken of the victim’s native place “衡水枣强 (Zaoqiang, Hengshui)” accurately and emphasized in Line 3 that the hometown is there, aiming to tell the victim that “I have got your detailed personal information based on our investigation”. Then the fraudster says in a much more threatening clause in the new turn in Lines 4 and 5 to strengthen the sharing information above. The fraudster uses information sharing to construct his false identity as a gang leader, triggering the victim’s fear.

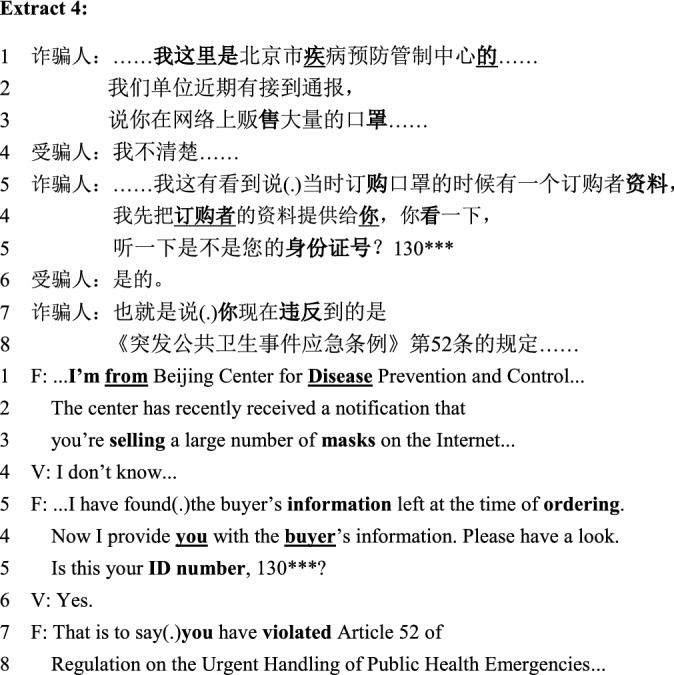

Sometimes fraudsters construct their false identities as staff in government departments to deceive victims. Case 20 is reported on Tencent and Sina as follows: on 3rd March 2020, Anti-fraud Center of Beijing Daxing District Public Security Bureau released a recording of a cellphone fraud related to the COVID-19 epidemic, in which a woman victim suddenly received a phone call about her illegal sales of masks and the fraudster gradually introduced her into a trap.

In Line 1 of Extract 4 from Case 20 (00:02–00:55), the fraudster introduces his identity as a staff in Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control to gain the victim’s trust. Following the fraudster’s warning statement in the next turn about illegal sales of masks, the victim casts a little doubt with the turn “我不清楚 (I don’t know)” on the fraudster’s indirect threat. The fraudster then asks the victim to confirm the so-called buyer’s personal information, i.e. whether 130*** is the victim’s ID number. After the victim’s confirmation and based on the sharing ID number, the fraudster changes to a new turn in Lines 7 and 8 about the victim’s violation of “《突发公共卫生事件应急条例》第52条的规定 (Article 52 of Regulation on the Urgent Handling of Public Health Emergencies)”. It means that the woman should be investigated for criminal responsibility according to the law. Consequently, the woman victim begins to be panic, and the fraudster has reinforced his false identity and put the victim under much mental pressure.

In summary, fraudsters, through turn-taking designs, make full use of information gaps or sharing information to construct false identities. In the process of fraudulent discourse development, fraudsters carry out direct or indirect threats to victims, and allows victims to enter their preset discursive sequences and psychological interactions.

Fraudsters’ Conversational Skills to Trigger Victims’ Panic

Repetition and Interruption

Repetition, one of conversational skills, bears emphasized or other rhetorical effect in conversations [43]. Thus, except for scary words or clauses for threatening victims directly, fraudsters use repetition to manipulate victims’ speech, and even threaten victims directly or indirectly to trigger their panic. For example,

In Extract 2, the fraudster repeats his threatening utterance to deal with the victim’s three requests to go to the police station for the justification of her innocence. When the victim asks to go to the police station for the first time, the fraudster replies with the clause “检察长都要来逮捕你了 (the chief procurator is coming to arrest you)” in a direct threatening tone. For a second time, the fraudster tries to increase the pressure on the victim with a similar repetitive threatening expression “你是要被立马性地拘捕的 (you will be arrested immediately)” in a much louder sound. For a third time, when the victim mentions to go to the station with a crying sound, the fraudster uses a direct threat consisting of a future action [20] by himself “我现在叫人把你带到看守所 (I’ll have you taken to jail now)” in a much louder and more terrible voice to further threaten the victim, and with the word “现在 (now)” to construct a false immediate reality. The word choices also demonstrate that the fraudster’s repetition skill has put increasing pressure on the victim and further constructed the fraudster’s false police identity and the fact that the victim is involved in a money laundering case. The fraudster’s repetition has achieved at least two communication goals, one is for the victim’s trust in his police identity, the other is for his refusal of the victim’s request.

As another conversational skill, interruption may be used by fraudsters to restrict turn allocations to victims in the threatening fraud interactions. Sacks et al. [38] discussed transition relevance places (TRPs) in the turn-taking system, and interruption might occur, if a speaker does not produce his words at TRPs. Victims’ speech may be interrupted and controlled by fraudsters and victims’ psychological pressure and panic may be aggravated indirectly by the unbalanced and unequal discursive power. Take Case 01 from Chinanews website as an example, in which the fraudster is constantly changing means to deceive the victim into handing over money.

In Extract 5 of Case 01 (00:33–01:01), the fraudster contacts the victim who transferred some money to him several days ago. In the first turn, the woman victim asks why she could not get through to the fraudster’s cellphone the day before, and she tries to know how her money transferred last time helps deal with the criminal case involved her. But the fraudster continues in Lines 2–3 to deceive the victim that he was on duty to catch the accomplices involved. In the next turn in Line 4, the victim wants to get some information on her money, but her utterance “你是 (Are you)” has been interrupted by the fraudster. On the one hand, the interruption has disrupted the victim’s thought about the inquiry of her money, resulting in the victim’s repetition of her own expression “我说你抓到了没有嘛? (I said if you’ve caught them?)” in Line 6. On the other hand, the fraudster can take control of the victim again for his ongoing deception action or prepared threatening fraud scripts. Consequently, until the last turn in Line 8 can the victim get the chance to inquire about her money.

Suprasegmental Skills

As one of relevant acoustic parameters for conversation analysis, prosody includes suprasegmental elements of speech such as pitch, intensity, prolonged sounds, speech rate and so on [37]. Fraudsters talk on the phone to trigger victims’ panic by prosodic designs in threatening fraud interactions. The acoustic analyses such as pitch or intensity for the present study are conducted with Praat 6.1.16 [6].

The cellphone conversation in Case 04 reported on the Kankanews has been collected by the police from one of the fraudsters’ recording pens. The reporter uses the typical conversation to tell people how a phone caller, before whom there is only a phone, a piece of paper and a pen, becomes as a “a best actor or actress” as a phone fraudster and teach people how to take care of their own money bags.

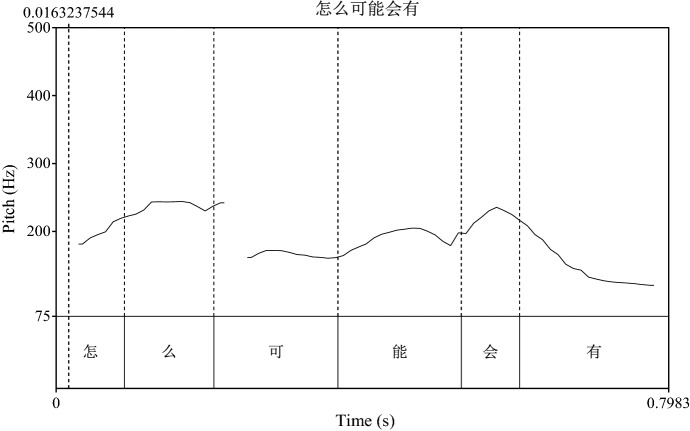

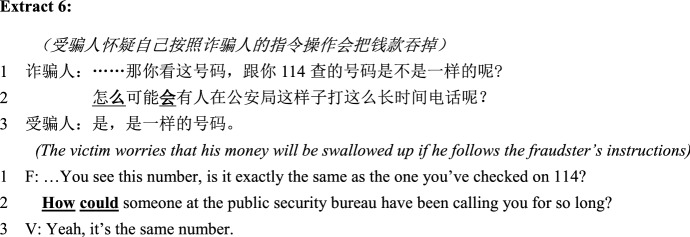

In Extract 6 of Case 04 (01:13–01:23), the victim doubts whether the money from her debit card will be transferred to a certain fraudster’s account rather than to the police’s, and the fraudster uses prosodic skill to control the victim. The two words “怎么 (How)” and “会 (could)” in the fraudster’s question step sharply up to a higher pitch, with the pitch movements visualized in the frequency analysis in Fig. 1. The rising pitch movements and the two pitch peaks serve as a cue to the emphasized meanings [37], one is for questioning the victim rhetorically, the other for telling the victim an obvious answer “I am a policeman in the station”.

Fig. 1.

Rising pitch contour of two rhetorical CHAs

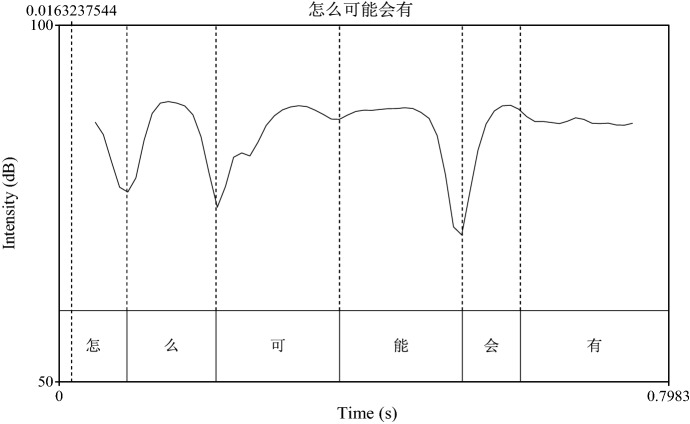

“Prominence is achieved through an increase in loudness and pitch ([37]: 6)”, so the fraudster simultaneously raises his voice in uttering the two characters “(怎)么 (How)” and “会 (could)” with the intensities of “么” and “会” taking on the upward trend in Fig. 2. In the speech, the fraudster attempts to express his angry in much louder voice for the same rhetorical purpose of putting the victim in fear.

Fig. 2.

Rising intensity contour of two rhetorical CHAs

The fraudster’s higher pitch and rising intensity create another type of indirect threat, which produce much more serious effect, as the victim immediately responds with a clause “是一样的号码 (Yeah, it’s the same number)” for the interactional alignment with the fraudster.

In Case 03, the cellphone fraud news reported on GRT Satellite Channel, a victim has been cheated of 500,000 RMB. Although the old method of impersonating a policeman has been used, it has also been integrated with new tricks by the fraudster.

In Extract 7 of Case 03 (01:00–01:18), the “if–then” construction can be identified as a direct threat [21], in which the fraudster also threatens the victim by means of rising intensity of some key words and syllables. It can be shown in Fig. 3 that the intensities of the five characters “及刑事拘捕 (arrested on a criminal charge)” take on five increasing peaks and a rising contour as a whole. This example of intensity matching occurs in the fraudulent sequence, in which the fraudster directly threatens the victim by raising his voice when the victim, in spite of nervousness, begins to doubt the fraudster’s false police identity and hesitates to do as the fraudster asks.

Fig. 3.

Rising intensity contour of five rhetorical CHAs

In the fraud process of Case 16, the news about impersonating the police reported on JSBC (Jiangsu Broadcasting Corporation), fraudsters expand all kinds of tricks to make their victims panic. But the purpose remains the same, to ask victims to transfer money. The news hostess suggests that all of us polish eyes when receiving a similar call, keep calm firstly, ignore kinds of threats, and directly call 110 to verify any possible question.

“Time is realized in the form of duration, tempo, speech rate, rhythm and pause ([37]: 3)”. In Extract 8 of Case 16 (01:52–02:43), the fraudster firstly slows his speech to tell the victim that he is involved in a serious criminal case of drug trafficking and money laundering. In order to further the threat directly, the fraudster then uses an alternative question in a new turn “现在是你要自己来投案自首, > 还是我们开警车去逮你啊? < (Now you come to the police to confess, > or we drive a police car to arrest you? <)”. In the second part of the question, the sudden faster speech forces the victim to make a choice immediately. But it is difficult for the victim to respond because a typical alternative question needs a mutually exclusive answer [5]. Alternative questions boost some functional features in cognition, such as to introduce listeners’ thinking about the answer, listeners’ reflection on something or listeners’ idea on something. Thus, no matter which one to choose, the victim is unwilling to face either of the two terrible situations, not to mention the action that the police come to arrest him. Thus, the victim’s fear has been heightened.

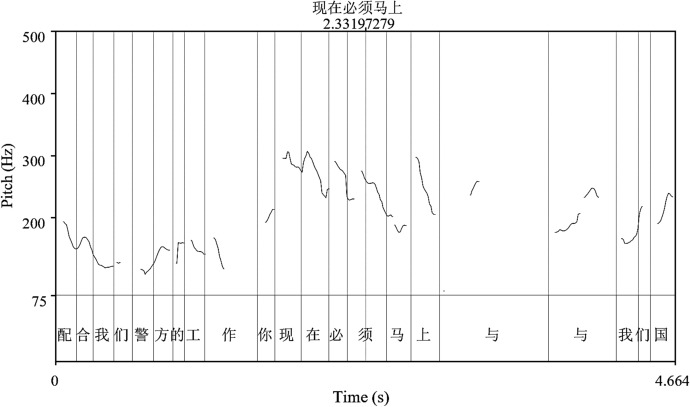

When the victim questions the fraudster’s description with the turn in Line 7, the fraudster has changed the topic to a so-called more complicated matter in the next turn in Lines 9–10, i.e. the victim’s possible personal information leakage and definite identity as a criminal suspect. So, in Line 11, the fraudster then tells the victim that he has to cooperate with the police. At the end of this turn in Line 12, the fraudster suddenly raises his pitch (see Fig. 4) to order the victim to contact the so-called “国家银联管理中心 (National Unionpay Management Center)”. Here the pitch contours of the Chinese characters “现在必须马上 (now must immediately)” are much higher than those preceding or following ones, in which “现在 (now)” and “马上 (immediately)” are used to urge the victim to take action without delay, and “必须 (must)” for the tone of an order. Here the fraudster aims to directly exert much more psychological pressure over the victim and further control of the victim’s action.

Fig. 4.

Much higher pitch contour of rhetorical CHAs

In summary, fraudsters often make timely choices of conversation skills such as repetition, interruption, louder voice, sudden pitch rising or speeding up utterance in threatening fraud interactions. And fraudsters attempt to cause victims’ psychological panic in threatening tones, in which victims may thoroughly believe their troubles in crimes or may be forced into fraud traps.

Fraudsters’ Discursive Practices Situated for the Threatening Actions

Fraudsters’ Discursive Devices Used in Preconceived Situations

Since “in methodological terms, the discourse can be analyzed for how it is put together to perform activities [36]”, fraudsters show their unique discursive devices which have been prepared and designed scripts in preconceived situations.

“DP is concerned with discourse in social interaction and how it is constructed to accomplish particular actions in specific contexts ([46]: 8)”. The statistical analysis here has fully demonstrated that fraudsters use direct and indirect threats of clauses to have victims being forced to be entrapped. It can be seen in Table 1 that 266 threat clauses in the twenty audio clips are indirect ones, accounting for 79.4% of the total, and 69 direct ones, taking only up 20.6%. The categorization of threats has also revealed how those threatening languages work in the interaction (see examples in Table 1). Fraudsters always construct a disquieting situation through indirect threats especially at the beginning of cellphone conversation while they suppress victims with direct threats in a pinch, resulting in victims’ psychological defense collapsed. According to the comments from CCTV news in Case 14, the 3-h cellphone fraud conversation is recorded by the fraudster herself simultaneously for use as a training book, following a carefully prepared script. Indirect threats are used at the first step to win victims’ trust, and then fraudsters begin to terrify and control their victims in forceful, harsh and direct threatening tones.

Table 1.

Fraudsters’ direct and indirect threats

| Types of threats (clauses) | Examples | Freq. | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct threats |

“要逮到你了, 我就割你的舌头 (If I catch you, I’ll cut off your tongue.)”(07:28–07:31 in Case 11) “要先行拘留你45天 (You will be held in detention for 45 days.)”(02:28–02:30 in Case 14) |

69 | 20.6 |

| Indirect threats |

“你今天涉及到的案例叫做刘**案件 (The case you’re involved in today is called Liu** Case)” (00:00–00:02 in Case 09) “现在确实有一部北京的手机号登记在您的名下, 并且涉及到了诈骗的违法行为 (Now here is indeed a Beijing cellphone number registered in your name, and involved in the fraud.)”(00:10–00:18 in Case 10) |

266 | 79.4 |

| Total | 335 | 100 |

At the micro-level, the integrity of conversational skills is often used by fraudsters for trapping victims in prepared discursive sequences. Table 2 below shows the frequencies of four types of conversational skills used in fraudsters’ threatening language, in which repetition and interruption are counted in clauses and suprasegmental skills in syllables. Statistically, 335 threat clauses in the 20 clips consist of 41 repetitions (accounting for 12.2% of all) and 32 times of interruption (9.6%), in which repetitions are often used by fraudsters to emphasize their preys’ troubles while interruption always for stopping victims’ doubts. Data analysis shows that no conversational skill does not work more effectively together with other ones. In order to exert more and more pressure over victims, fraudsters use repetition or interruption skills with suprasegmental ones like loudness or higher pitches for stress (see Extract 2). As for suprasegmental skills, higher pitches amount to 1065, taking up 26.9% of all the 3948 syllables; increasing intensities to 1333, accounting for 33.8%. Data analysis has found that higher pitch and increasing intensity have always been carried in same syllables, which shows that fraudsters try to reinforce the threat of those Chinese words (also see Extract 2).

Table 2.

Fraudsters’ conversational skills

| Conversational skills | Clauses | Syllables | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | |

| Repetition | 41 | 12.2 | ||

| Interruption | 32 | 9.6 | ||

| Higher pitch | 1065 | 26.9 | ||

| Increasing intensity | 1333 | 33.8 | ||

| Total | 335 | 3948 | ||

At the macro-level, fraudsters’ threatening utterances collaboratively promote discourse development according to the prepared scripts in that language use exists in contexts but beyond materials in the discourse [2]. Smooth development of fraud discourse is embodied through fraudsters’ prepared turn-taking system. Cellphone fraudsters do not work independently but in fraud groups, and their cellphone speeches are not uttered casually or spontaneously but in accordance with fraud scripts. In the threatening fraud interactions, fraudsters transmit prepared information through prepared turns to promote the discourse development as what they want. Prepared turns usually include such sharing information with victims as victims’ names, identity card numbers, addresses and so on, and some new information like victims’ guilt involved in criminal cases [50]. It is the combination information gaps and information sharing that help fraudsters bring victims’ thoughts and discourse into fraudulent discourse development.

Situation-Based Implications for Preventing Cellphone frauds

Cellphone fraudsters’ fictive actions bring victims into psychological vulnerability with power manipulation and position control in specific situations. DP examines “how and when identities shift discursively in face-to-face or online interaction” ([46]: 63). In accordance with the data analyzed above and the legal opinions or legal education from the police and mainstream media, two points should be noted for preventing cellphone frauds.

On the one hand, fraudsters always predesign several steps based on the specific fraud interaction, and employ discursive strategies to make victims’ psychological change more deeply and bring victims into prepared sequence organizations. For example, people should pay much more attention to the five steps of cellphone frauds, in which fraudsters impersonate gang members. In Case 08, the fraudster gradually intensifies the victim’s panic in four steps so that he has successfully controlled the victim with his discursive power. It is the first step that the fraudster informs the victim that he is being tracked through sharing the victim’s personal information purchased online. The second step for the fraudster is to fabricate a story to initiate the threat to the victim in that the fraudster tells the victim that he has offended someone and the person who has paid the so-called gangdom for revenge on the victim. For the next step, the fraudster’s utterances perform the function to verify whether the victim has entered the play and whether the victim hopes to pay for the elimination of the disaster. In the fourth step, the fraudster reinforces the threat to further intimidate the victim in that the fraudster makes up a nickname that sounds tough enough and releases such cruel words as “刀尖上舔血 (licking blood on the tip of the knife)” and “白刀子进红刀子出 (white knife in, red knife out)”. After the fraudster’s four-step escalation of verbal violence, if the victim has been found in the tone of fear, the fraudster will carry out the fifth step to ask for money.

On the other hand, it is the most important for people to improve information security awareness and enhance the ability to prevent frauds. It is suggested that the following reminders be remembered. Firstly, Bank card password or verification code is the last line of defense for capital security. Secondly, the public security authorities have never handled cases on the phone or video, have no so-called “safe account” and have never asked people to transfer money to it. Thirdly, the public security authorities have not realized direct communication with any other institution, department or company. Fourthly, it is a fraudulent action that someone frames your illegal sales of epidemic supplies. Fifthly, if there is an unfamiliar call asking for bills, dial the service hotline directly. Sixthly, if there is a threat from so-called gang members, call the police immediately.

Conclusion

The present study describes fraudsters’ false identity construction in the threatening fraud interactions, examines fraudsters’ conversational skills and discursive strategies for their fraud purposes. The findings include: (1) fraudsters’ predetermined false identities are constructed and invoked through information gap and information sharing in the threatening fraud interactions; (2) in the false identity construction process, different conversational skills are used by fraudsters to threaten and entrap victims; (3) fraudsters’ discursive practices are situated for the threatening actions based on prepared and designed scripts.

The present study not only conduces to the deep understanding of cellphone fraudsters’ threatening language in the fraud interactions, but provides a discursive psychological pathway to explore cellphone fraud at both macro-level and micro-level. The findings of the study are expected to provide references for the people’s fight against fraudsters’ threats and bullies, and for the people’s prevention of cellphone frauds. However, the study only focuses on the analysis of online audio or video data. As matter of a fact, it is necessary to carry out the interviews with fraudsters and victims for validity and reliability. In the future, with the help of public security authorities, face-to-face interviews with fraudsters and victims will be made for the in-depth empirical studies to support discursive psychological findings.

Acknowledgements

This paper is a part of the National Social Sciences Research Foundation entitled “A Corpus-based Study of the Identification of Telecom Fraud Discourse and its Application (No. 18BYY073)” and is funded by Guangdong Philosophy and Social Science Research Program (No. GD19CYY07). I am deeply grateful to Prof. Anne Wagner for her patience and support in the paper writing process. My sincere thanks is expressed to anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and valuable suggestions.

Appendix 1: Transcription conventions

- ……

Ellipsis

- Word

Higher pitch for emphasized syllable

- ()

Comments, reported speech or thought

- ▲▼

Interruption

- ::

Prolonged syllable; the more colons, the more elongation

- (0.5)(2.6)

Pause duration (0.5 or 2.6 s)

- (.)

Micro pause (shorter than 0.5 s)

- ºwordº

Quieter and softer speech

- ><

Speeding up utterance

- <>

Slowing down utterance

- []

The start and end of overlapping speech

- ↑ ↓

Upward arrows indicate a rising pitch in talk, downward arrows indicate falling pitch

- Bold

Speech that is obviously louder than surrounding speech

- hh

hhs indicate audible breaths. A dot followed by hs (.h) indicate audible inbreaths; without the dot (as in hh) is an outbreath. The more hs, the longer the breath

Appendix 2: General information on the cases

| Case no. | Titles of cases | Source of videos or audios, titles or hypertexts |

|---|---|---|

| 01 | 女子遭遇电信诈骗 曝光全程电话录音(Woman encountered telecom fraud and released the phone recording) | http://www.chinanews.com/shipin/2016/11-01/news674398.shtml |

| 02 | “6·25”特大电信网络诈骗案告破 警方缴获诈骗录音 揭露行骗伎俩(The recording of “June 25” telecom fraud case reveals deception tricks) | https://haokan.baidu.com/v?pd=wisenatural&vid=14312016622740205208 |

| 03 | 新型电信诈骗 事主公开诈骗录音 (In a new type of telecom fraud the victim released the recording) | http://tv.sohu.com/20140128/n394318914.shtml |

| 04 | 沪警方捣毁电信诈骗窝点 还原诈骗电话录音 (Shanghai police smashed the telecom fraud and released the fraud recordings) | http://www.kankanews.com/a/2015-11-08/0037210323.shtml |

| 05 | 电话录音揭示跨国电信诈骗团伙如何套取信息:女士被吓哭 (Phone calls reveal how transnational telecom fraud groups get messages: Woman victim scared to cry) | https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1396001 |

| 06 | 电话录音 男子电话冒充黑社会平事儿诈骗 (In a cellphone recording a man impersonates a gang member) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/b0555c19ags.html |

| 07 | 遭遇匿名电话威胁 实为电信诈骗新招 (Threatened by an anonymous phone call a new way for telecom fraud) | http://news.cntv.cn/2015/10/07/VIDE1444185490322327.shtml |

| 08 | 起底电信诈骗术之“我是黑社会” 诈骗原声录音 诈骗有剧本有套路 (Human flesh search: the original sound recording of a telecom fraud “I am a gang member” reveals there are scripts and tricks) | http://tv.cctv.com/2016/04/28/VIDEj613Vp25vKz7RteVoidE160428.shtml |

| 09 | 电信诈骗冒充公检法通话录音 (In a cellphone recording the telecom fraudster impersonates a public security member) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/x0975307rwh.html |

| 10 | 电信诈骗通话录音 (A cellphone recording of telecom fraud) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/a0367m7thuy.html |

| 11 | 恐吓诈骗电话录音_听听有好处 (Useful to listen: a cellphone recording of threatening fraud) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/j01395y5bt4.html#vfrm=2-3-0-1 |

| 12 | 别信那些骗人的话 湖北公安厅发布“诈骗录音”征集令 (Don’t believe those deceptive words Hubei Public Security Department has issued a solicitation for “fraudulent recording”) | http://news.cntv.cn/2014/10/16/VIDE1413424810808892.shtml |

| 13 | 大学生遭电信诈骗 录音记录骗子伎俩 (A college student involved in a telecom fraud recorded fraud tricks) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/o3031p475y0.html |

| 14 | 电信诈骗录音曝光:步步直逼诱人入局 (Telecom fraud recording: enticing victims into deceptions step by step) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/h03005ks19t.html |

| 15 | 诈骗变种!团伙冒充公检法借疫情诈骗近300万元 电话录音揭露诈骗过程 (Variety of fraud! The group pretend to be the public security members during the COVID-19 epidemic, and deceived nearly of 3 million RMB. Cellphone recordings have revealed the fraud process) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/b09428c045j.html |

| 16 | 电信诈骗冒充警察恐吓市民 (Telecom fraud: impersonate the police to intimidate people) | https://v.qq.com/x/cover/5uqy1tzpsbaffda/B00103D01Nr.html |

| 17 | 诈骗电话录音 (Fraud call recording) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/n03368a9ln5.html |

| 18 | 诈骗电话录音 (Fraud call recording) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/l0155kp1etl.html |

| 19 | 疫情期间“碟中谍”骗局,涉疫诈骗团 (“Mission: Impossible” during the epidemic, COVID-19 fraud team) | https://v.qq.com/x/page/d09577e1rg2.html |

| 20 | 真实诈骗录音!骗子冒充警察诈骗!警惕! (Real fraud recording! Fraudsters posing as the police! Alert!) |

https://v.qq.com/x/page/c09691rbehe.html, http://k.sina.com.cn/article_3164957712_bca56c10020016qm9.html?from=news&subch=onews |

Footnotes

The interaction period for analysis from 00:23 to 01:18 in the video or audio, the same below.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Albrecht W Steve, Albrecht Chad, Albrecht Conan C. Current Trends in Fraud and Its Detection. Information Security Journal: A Global Perspective. 2008;17:2–12. doi: 10.1080/19393550801934331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvesson Mats, Karreman Dan. Varieties of Discourse: On the Study of Organizations Through Discourse Analysis. Human Relations. 2000;53(9):1125–1149. doi: 10.1177/0018726700539002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Augoustinos, Martha, and Simon Goodman. 2017. Discursive Psychological Approaches to Intergroup Communication. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. https://oxfordre.com/communication/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-377#acrefore-9780190228613-e-377-div1-2.

- 4.Austin John L. How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biezma María, Rawlins Kyle. Alternative Questions. Language and Linguistics Compass. 2015;9(11):450–468. doi: 10.1111/lnc3.12161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. Praat: Doing Phonetics by Computer [Computer program][DB/CD]. Version 6.1.13, 2020. http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/praat/.

- 7.Cheng Le, Gong Mingyu, Li Jian. Equivalence in Legal Translation: From a Sociosemiotic Perspective. Journal of Zhejiang University (Humanities and Social Sciences) 2016;46(4):77–90. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-942x.CN33-6000/C.2015.09.213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiluwa Innocent. The discourse of digital deceptions and ‘419’ emails. Discourse Studies. 2009;11(6):635–660. doi: 10.1177/1461445609347229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins Michael. Telecommunications Crime—Part 1. Computer & Security. 1999;18(7):577–586. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4048(99)82004-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins Michael. Telecommunications Crime—Part 2. Computer & Security. 1999;18(8):683–692. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4048(99)80132-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins Michael. Telecommunications Crime—Part 3. Computer & Security. 2000;19(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4048(00)87824-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cox Kenneth C, Eick Stephen G, Wills Graham J, Brachman Ronald J. Brief Application Description; Visual Data Mining: Recognizing Telephone Calling Fraud. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 1997;2:225–231. doi: 10.1023/a:1009740009307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drew Paul, Heritage John. Talk at Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du Jinbang. Information Flow in Discourse. Journal of Foreign Languages. 2009;32(3):36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Edwards Derek, Potter Jonathan. Discursive Psychology. London: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards Derek, Potter Jonathan. Discursive Psychology. In: McHoul Alec, Rapley Mark., editors. How to Analyse Talk in Institutional Settings: A Casebook of Methods. London: Continuum International Publishing Group; 2001. pp. 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fraser Bruce. Threatening Revisited. Forensic Linguistics (The International Journal of Speech, Language and the Law) 1998;5(2):159–173. doi: 10.1558/sll.1998.5.2.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freiermuth Mark r. Text, Lies and Electronic Bait: An Analysis of Email Fraud and the Decisions of the Unsuspecting. Discourse & Communication. 2011;5(2):123–145. doi: 10.1177/1750481310395448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gales Tammy. Identifying Interpersonal Stance in Threatening Discourse: An Appraisal Analysis. Discourse Studies. 2011;13(1):27–46. doi: 10.1177/1461445610387735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gingiss Peter. Indirect Threats. Word. 1986;37(3):153–158. doi: 10.1080/00437956.1986.11435774. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hepburn Alexa, Potter Jonathan. Threats: Power, Family Mealtimes, and Social Influence. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2011;50(1):99–120. doi: 10.1348/014466610X500791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heritage, John. 1998. Conversation Analysis and Institutional Talk: Analyzing Distinctive Turn-Taking Systems. In Proceedings of the 6th International Congress of IADA, ed. S. Cmejrková, J. Hoffmannová, O. Müllerová, and J. Svetlá, 3–17. Tubingen: Niemeyer.

- 23.Hoath Peter. Telecoms Fraud, The Gory Details. Computer Fraud & Security. 1998;1:10–14. doi: 10.1016/s1361-3723(97)82712-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Xiaoliang, Wang Zhoucheng. The Cooperation on the Prevention and Punishment of Telecom Frauds in the Big-Data Era. Guizhou Social Sciences. 2016;2:164–168. doi: 10.13713/j.cnki.cssci.2016.02.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutchby Ian, Wooffitt Robin. Conversation Analysis: Principles, Practices and Applications. Cambridge: Polity Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ladefoged Peter, Johnson Keith. A Course in Phonetics. 7. Stamford: Cengage Learning; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Hong. An Analysis of Difficult Issues in Telecom Frauds. Law Science. 2017;5:166–180. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li Li. Social Interaction and Teacher Cognition. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molder H. Discursive Psychology. In: Tracy Karen, Ilie Cornelia, Sandel Todd., editors. The International Encyclopedia of Language and Social Interaction. 1. New Jersey: Wiley; 2015. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muschalik Julia. Threatening in English: A Mixed Method Approach. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ni Shifeng, Cheng Le, Sin King Kui. Who are Chinese Citizens? A Legislative Language Inquiry. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. 2010;23(4):475–494. doi: 10.1007/s11196-010-9167-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Brien John T. Telecommunications Fraud. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin. 1998 doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6170-8_100076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Onyebadi Uche, Park Jiwoo. ‘I’m Sister Maria. Please Help Me’: A Lexical Study of 4-1-9 International Advance Fee Fraud Email Communications. The International Communication Gazette. 2012;74(2):181–199. doi: 10.1177/1748048511432602. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pomerantz Anita, Fehr BJ. Conversation Analysis: An Approach to the Study of social Action and Sense-making Practices. In: Van Dijk Teun A., editor. Discourse as a Social Interaction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potter Jonathan, Wetherell Margaret. Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour. London: Sage; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potter Jonathan. Discursive Psychology: Between Method and Paradigm. Discourse & Society. 2003;14(6):783–794. doi: 10.1177/09579265030146005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reed Beatrice S. Prosodic Orientation in English Conversation. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sacks Harvey, Schegloff Emanuel A, Jefferson Gail. A Simplest Systematics for the Organization of Turn-Taking for Conversation. Language. 1974;50:696–735. doi: 10.1353/lan.1974.0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacks Harvey. Lecture 10: Pro-verbs; Performatives; Position Markers; Warnings (1966) In: Jefferson Gail., editor. Lectures on Conversation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell; 1992. pp. 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salgueiro Antonio B. Promises, Threats, and the Foundations of Speech Act Theory. Pragmatics. 2010;20(2):213–228. doi: 10.1075/prag.20.2.05bla. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sneijder Petra, Stinesen Baukje, Harmelink Maartje, Klarenbeek Annette. Monitoring Mobilization: A Discursive Psychological Analysis of Online Mobilizing Practices. Journal of Communication Management. 2018;22(1):14–27. doi: 10.1108/jcom-12-2016-0094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subudhi Sharmila, Panigrahi Suvasini. Use of Possibilistic Fuzzy C-means Clustering for Telecom Fraud Detection. In: Behera Himansu Sekhar, Mohapatra Durga Prasad., editors. Computational Intelligence in Data Mining. Singapore: Springer; 2017. pp. 633–641. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tannen Deborah. Talking Voices: Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational Discourse. 2. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walton Douglas N. Scare Tactics. Dordrecht: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang Xiaowei. On Idea Renewal and Mechanism Innovation of Fighting Against Telecom Frauds. People’s Tribune. 2016;2:42–44. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-3381.2016.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wiggins Sally. Discursive Psychology: Theory, Method and Applications. Los Angeles: Sage; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Chaoping. The Development of Telefraud under the Background of “Internet +” and Its Prevention and Control. Journal of People’s Public Security University of China (Social Science Edition) 2015;6:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamanaka Nobuhiko. On Indirect Threats. International Journal for the Semiotics of Law. 1995;8(1):37–52. doi: 10.1007/BF01677089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ye Ning, Cheng Le, Zhao Yun. Identity Construction of Suspects in Telecom and Internet Fraud Discourse: From a Sociosemiotic Perspective. Social Semiotics. 2019;29(3):319–335. doi: 10.1080/10350330.2019.1587847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan Ying. Research on Discourse Patterns and Speech Strategies in Telecom Fraud Cases. Journal of Guizhou Police Officer Vocational College. 2019 doi: 10.13310/j.cnki.gzjy.2019.04.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]