Abstract

Since its invention in 1986, atomic force microscopy (AFM) has grown from a system designed for imaging inorganic surfaces to a tool used to probe the biophysical properties of living cells and tissues. AFM is a scanning probe technique and uses a pyramidal tip attached to a flexible cantilever to scan across a surface, producing a highly detailed image. While many research articles include AFM images, fewer include force-distance curves, from which several biophysical properties can be determined. In a single force-distance curve, the cantilever is lowered and raised from the surface, while the forces between the tip and the surface are monitored. Modern AFM has a wide variety of applications, but this review will focus on exploring the mechanobiology of microbes, which we believe is of particular interest to those studying biomaterials. We briefly discuss experimental design as well as different ways of extracting meaningful values related to cell surface elasticity, cell stiffness, and cell adhesion from force-distance curves. We also highlight both classic and recent experiments using AFM to illuminate microbial biophysical properties.

Keywords: atomic force microscopy, force–distance curve, membrane elasticity, cell stiffness, adhesion, microbes

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION: BIOLOGY AT THE NANOSCALE

When atomic force microscopy (AFM) was first introduced in 1986, its application was primarily tailored to obtaining high-resolution images of inorganic surfaces.1 However, with several technical advances from the initial design, AFM has become a powerful tool for investigating biological systems, providing topographical images at nanoscale resolution.2–7 In a standard AFM imaging experiment, a pyramidal tip attached to a flexible cantilever (Figure 1A) is moved across the surface of a sample. A beam of light is focused on the back of the tip, and the deflection of the light as the tip moves across the surface is used to generate a detailed image (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic representation of the AFM cantilever from both the side and above as well as (B) basic AFM operating principles. Figures are not drawn to scale.

Initially, images were acquired in contact mode, in which the tip contacts the surface and scans back and forth to generate an image.1 In contact mode imaging, a piezo adjusts the height of the tip to maintain a constant force on the surface. Noncontact mode imaging was developed only a year later,8 and further improved upon with the introduction of alternating contact (AC) mode,9,10 which made possible huge progress in imaging biomaterials. In AC mode, a piezo oscillates the tip at near-resonance amplitude and frequency, minimizing the force and friction between the tip and the surface, and allowing topographic imaging with high resolution and minimal damage to soft biological samples. Even before AC imaging was introduced, fluid cells were constructed, allowing experimenta-tion on biological substrates to occur under native conditions.2,11 The development of smaller tips, which increased the speed at which images could be obtained, further refined AFM as a technique suitable for investigating biological material12 and paved the way for high-speed AFM imaging.13 Today, thousands of research articles have been published using AFM to image everything from atomic bonds to eukaryotic tissues. 6,7,14–18

MECHANOBIOLOGY: MAY THE FORCE BE WITH YOU

While images might represent the majority of data obtained with AFM, the tip can also be used to probe the biophysical characteristics of samples, providing biomechanical information such as stiffness, elasticity, and adhesion. Though some of these values can be obtained through other experimental techniques (contact angle, electrophoretic mobility measurements, and infrared spectroscopy), AFM experiments can capture data under near-native conditions.3 Furthermore, complex biological interactions can be interrogated by modifying either the surface or the tip. To avoid complications in data analysis caused by capillary forces between the tip and the surface,5,19 force experiments on biological systems are usually carried out in fluid. While the basic experimental set up and analysis are similar for many samples, we will explore the acquisition of force data from microbes in this review, which is our area of expertise and we believe to be of particular interest to those researchers investigating biomaterials.

Experimental Setup

There are several ways in which an AFM experiment might be designed to obtain force data (Figure 2).20 Regardless of experimental design, the cells must be transferred from a liquid culture and adhered to either the surface or the cantilever. Since cells are typically nonadherent to surfaces commonly used for AFM, immobilization of samples is an important prerequisite to scanning, data collection, and evaluation of biophysical properties. There are several methods of attaching bacterial cells to a surface,21,22 the most common of which involves creating positive charges across the surface by depositing a layer of poly-L-lysine.23 While poly-L-lysine is suffcient for many organisms, we have found Corning Cell-tak produces more robust and reliable adhesion.24 Many microbial cells can also form biofilms, organized communities surrounded by a layer of adhesive exopolymeric substances (EPS).25–28 Even cells that are not considered traditional biofilm formers can adhere to a glass coverslip under the right growth conditions.29 Growing cells as a biofilm does remove the need for an external fixation agent such as Cell-tak or poly-L-lysine. However, because the EPS also covers the surface of the cell, it is important that consideration be given to the influence of the EPS on the resulting force data.

Figure 2.

Three common experimental designs used to obtain force measurements. Cells may be (A) affxed to a surface and probed directly with the tip or (B) probed with a molecule attached to the tip. (C) Bacterial cells may also be affxed to the cantilever.

Though some studies have utilized chemical fixatives or agar pads to adhere yeast cells to a substrate, the most common practice for yeast cell immobilization involves trapping cells in polycarbonate porous membranes or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamps.30–32 Though these immobilization approaches can be more costly or diffcult to set up initially than alternative options, they provide a more physiologically relevant setting where cells can grow and be evaluated with decreased risk of detachment or lateral cell drift, which can be worth the added investment.

In the most common type of force experiment, cells are attached to a surface, and the AFM tip is lowered and raised to probe the cell (Figure 2A). Before the experiment starts, the tip is calibrated using a hard surface to determine the spring constant of the cantilever (kcantilever).33 A standard tip may be used or the tip may be coated with a material of interest. Adhering the cells to the surface is necessary for obtaining both standard AFM images and force measurements in a single experiment. It may also be preferable to adhere cells to the surface when investigating the interaction between the cell and small molecules (Figure 2B). In these experiments, the molecule of interest is bound to the tip and lowered to the cell surface. In this way it is possible to probe the interaction between a cell and a single molecule.34

The reverse experiment can also be performed, where the cell is adhered directly to the cantilever, though this type of experiment is usually limited to bacterial cells, due to their smaller size relative to the cantilever (Figure 2C). In these experiments, the tip has either been replaced by a spherical probe or removed entirely. To extract meaningful data, it is important to calibrate the cantilever before the cells are attached. Once the cantilever has been calibrated, it is treated to create a positively charged surface and then incubated with the cells. Once the cells are adhered to the cantilever, the cantilever is placed into the AFM and lowered to the surface to perform force measurements. These types of experiments are particularly useful for measuring adhesion between a cell and a treated surface. Cells can also be adhered to both the surface and the cantilever to monitor cell-cell interactions. While we have described some of the basic features of experimental design here, a more detailed review can be found in ref 20.

Experimental Analysis

In most force experiments, interaction forces are monitored as a function of the distance between the tip and sample. These forces are monitored both as the tip approaches and retracts from the surface, usually covering a distance of several microns, though specific distances need to be determined for individual experiments. Thus, a force experiment can be divided into two halves: the approach or extension curve, which provides information on the elasticity of the surface and the stiffness of the cell, and the retraction curve, which provides information on the adhesive properties of the cell surface. The y-axis of both curves is force, and the x-axis is distance (Figure 3). The origin is defined as the distance at which the cantilever first contacts the surface (Figure 3). While the cells may be attached to either the cantilever or the surface, the force data obtained from the experiment are equivalent. We will describe the data as if it were collected from an experiment in which the cells are attached to the surface and the tip is used to probe the cell.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of an approach curve. (A) The tip is lowered toward the cell surface (B) where it makes initial contact. (C) As the tip begins to push into the cell wall, there is a nonlinear change in force, which indicates the elasticity of the cell surface. (D) The tip pushes further on the cell and generates a linear change in force, from which the cell stiffness is calculated.

First, the AFM tip is lowered to the cell surface where it makes initial contact (Figure 3A,B). There are usually limited long-range interaction forces as the tip approaches the cell, resulting in a flat line as the first regime of the extension curve (Figure 3B). However, just before the tip makes physical contact with the cell, electrostatic and van der Waals forces can begin to form between the tip and the cellular surface. Combined with the initial physical interaction between tip and the cell, these forces generate a nonlinear change, marking the second regime in the extension curve, the nonlinear compression (Figure 3C). This regime can be reported as the change in force relative to the change in distance and reflects the elasticity of the cell wall.29,35 Various models are also used to fit the data, including the Hertz model, which is used to calculate Young’s modulus (a measure of elasticity), and the Alexander and de Gennes (AdG) model, which is used to describe the behavior of the polymers on the cell surface.36,37

As the tip continues to push on the cell, it encounters stronger resistance, transitioning from the nonlinear regime to a linear change in force, called the linear compression (Figure 3D). The tip continues to push on the cell until it meets a predetermined set point. Set points must be carefully determined as part of the experimental design so as not to inflict damage upon the cell. The interaction between the cantilever and the cell is modeled as the compression of two springs.38 The spring constant of the cell (kcell) and the spring constant of the cantilever (kcantilever ) are calculated from the slope of the linear compression (Figure 4). The slope of this regime is the keffective and relates to the kcell and kcantilever through eq 1:

| (1) |

Since the spring constant of the cantilever is determined at the beginning of the experiment,33 it is possible to quantitate the cell stiffness from the slope of the linear regime.38

Figure 4.

Interaction of the tip and the cell is modeled as a compression of two springs. The spring constant of the cantilever (kcantilever) is measured at the beginning of the experiment,and the keffective is determined from the slope of the linear compression.kcell is determined using eq 1.

Once the predetermined set point has been reached, the tip can dwell on the surface or it can be immediately retracted, beginning acquisition of a retraction curve (Figure 5A). As the tip is retracted, the interaction between the cell and the tip is essentially reversed, and the initial regime of the retraction curve should generally overlay the linear compression of the extension curve (Figure 5B). However, as the tip pulls away from the surface, adhesion forces may keep the tip and surface connected (Figure 5C). Eventually, the tip moves far enough away that the connection breaks, resulting in a snap-off, in which the force applied to the tip rapidly returns to zero (Figure 5D). Measuring the change in force associated with a snap-off provides information on the strength of the adhesive forces between the tip and the surface, while the change in distance provides information on how far the surface stretched. In bacteria, it is not uncommon to observe quite long distances, especially on strains that produce pilli.29

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of a retraction curve. (A) The tip begins to pull away from the cell, (B) with the data generally overlaying the linear compression of the approach curve. (C) Adhesive forces allow the tip and surface to remain connected, and the tip pulls the surface up (D). Eventually, the attractive forces are overcome and the tip and surface separate, creating a snap-off event in which the force rapidly returns to zero.

Force Mapping

While the force experiments described above result in a single force curve, force-distance (FD) mapping makes it possible to acquire force data across a surface, revealing the spatial distribution of biophysical properties.39,40 In FD mapping, a defined area is imaged while simultaneously probing the cell surface to acquire thousands of force curves on a point-by-point basis. This approach enables concurrent characterization of height, elasticity, and adhesion as the tip moves across a surface and allows reconstruction of a map with local biophysical properties along a given topography. Initial FD mapping was limited by poor spatial and temporal resolution due to the physical properties of the tip, the speed of the piezo controlling the cantilever, and the feedback between the tip and software. However, advances including smaller cantilevers with higher quality (Q)-factors, faster piezo control and feedback loops for the cantilever, and multiparametric imaging have contributed to drastic improvements in both spatial and temporal resolution.41–46 Under optimal conditions, a 512 X 512 pixel FD map with lateral resolution of approximately 1 nm can now be acquired in under 30 min.45 The more recent development of spectral-spatially encoded array AFM (SEA-AFM) promises to increase the temporal resolution even further without sacrificing sensitivity by using multiple cantilevers simultaneously deflecting different wavelengths of light.47 These technological advances have expanded the applicability of FD mapping beyond correlating surface nanoproperties with topography to being able to investigate dynamic cellular changes and fluctuations on increasingly rapid time scales.

FORCE EXPERIMENTS ON MICROBES

Nonlinear Regime: What Is Happening at the Surface?

The nonlinear regime is the first regime in the approach curve, from which we can extrapolate information about the cell. In microbes, this regime reflects the interaction between the tip and the cell wall, a variable structure that provides support and acts as a protective barrier. In bacteria, the parameters of this regime can reflect the negative electrostatic and van der Waals interactions between the tip and the surface as well as the initial deformation of the cell by the tip (Figure 3C).38,48 By analyzing the change in force and the change in distance that occur during this regime, we can determine the elasticity of the cell wall. The nonlinear regime can be fit with the Hertz model to derive Young’s modulus, and the elasticity of the cell wall is often reported as this value.36 A larger value for Young’s modulus indicates a stiffer surface, though it is more often a change in Young’s modulus that is of interest. The elasticity of the bacterial cell wall can also be reported as a change in force and a change in distance, which removes the assumptions necessary to calculate Young’s modulus.24,29,35

The elasticity of the cell wall is often of interest when microbes are exposed to an external agent that modifies some part of the cell wall structure. We have previously characterized the change in cell wall elasticity during predation by Bdellovibrio bacteriovorus, a bacterium that preys only on Gram-negative bacteria, which in these experiments were Escherichia coli (E. coli) biofilms.35 The Gram-negative cell wall is composed of an outer membrane, a thin layer of peptidoglycan contained in the periplasmic space, and an inner plasma membrane (Figure 6A).49 Bdellovibrio secretes various enzymes that modify and destabilize the cell wall, and we observed significant increases in both force and distance of the nonlinear regime during predation.35 These measurements allowed us to connect the biochemistry of invasion to the biophysical changes in the prey cell.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the Gram-negative cell wall. (A) The Gram-negative cell wall contains two membranes, the plasma membrane and the outer membrane, which sandwich the periplasmic space containing the peptidoglycan. (B) The outer leaflet of the outer membrane contains lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a highly diverse molecule. Different strains of bacteria have different polysaccharide combinations, with some strains containing many O-antigen units, while others contain only the inner core.

Silica nanoparticles 4 nm in diameter increased the elasticity of the Gram-negative cell wall, while nanoparticles with a 100 nm diameter had no effect.50 The authors suggest that the smaller size allows the nanoparticles to destabilize the outer membrane, and eventually destabilize the peptidoglycan, which leads to cell lysis. Treatment with common antibiotics is also capable of decreasing the stiffness of the Gram-negative cell wall, with important consequences. Formosa et al. used FD mapping to investigate the changes in the cell wall elasticity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) treated with ticarcillin, a ß-lactam antibiotic that disrupts assembly of the peptidoglycan layer.51 When the P. aeruginosa were treated with ticarcillin, Young’s modulus dropped from 263 ± 70 kPa to 50 ± 18 kPa, a dramatic decrease in the stiffness of the cell wall, and a value that reflects the lack of cross-linking in the peptidoglycan layer. Gaveau et al. later showed that treating a different strain of P. aeruginosa with ticarcillin not only increased the elasticity of the cell wall but also linked increased cell wall elasticity with the ability of treated cells to pass through sterilization filters.52

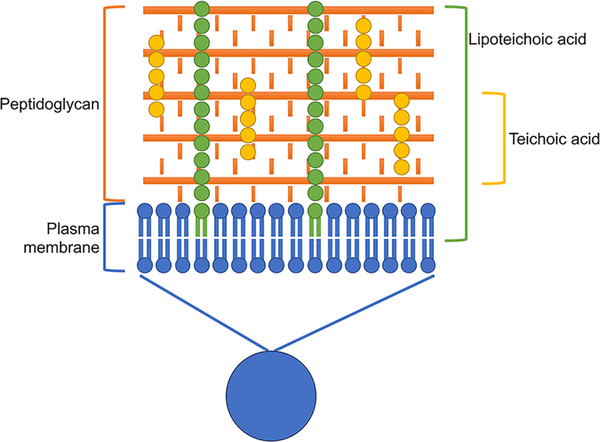

Gram-positive bacteria have a very different cell wall structure than the Gram-negative bacteria described above.49 Gram-positive cell walls are composed of a thick peptidoglycan layer, with lipoteichoic acids running from the plasma membrane through the peptidoglycan matrix, making a Gram-positive cell wall much stiffer (Figure 7). Thus, chemical and biological alterations to the Gram-positive cell wall often produce dramatic changes in stiffness. Using Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus), Francius et al. used force measurements to monitor the digestion of the peptidoglycan layer by the enzyme lysostaphin.53 The Young’s modulus of the S. aureus cell wall decreased from 1764 ± 218 kPa to 189 ± 49 kPa over the course of the digestion, indicating a cell wall almost ten-times more elastic after treatment. Others have investigated S. aureus mutants that lack peptidoglycan synthesis genes and observed a similar softening of the cell wall in the absence of peptidoglycan cross-linking.54

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the Gram-positive cell wall. The Gram-positive cell wall contains a single membrane with a thick peptidoglycan layer. Teichoic acids covalently bind to the peptidoglycan while lipoteichoic acids anchor the peptidoglycan to the plasma membrane.

Among yeast, the nanomechanical properties of the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) have been most widely studied by AFM. Yeast cells are surrounded by a 100–200 nm thick cell wall.55,56 Though yeast cell walls can vary in composition, they typically consist of linear and branched ß-glucan arrays (consisting primarily of ß-1,3- and ß-1,6-linkages) covered with a layer of heavily glycosylated mannoproteins (Figure 8).57,58 Despite the rigid architecture provided by these covalently cross-linked components, the yeast cell wall is also a highly dynamic structure capable of remodeling during mating, polarized growth, or response to environmental stimuli.36,59–61 Nanoindentation measurements reveal uniform elasticity along the cell wall during vegetative growth.62–64 However, extensive cell wall remodeling occurs during the process of bud formation in asexual reproduction, resulting in a 3- to 10-fold increase in stiffness at the bud site relative to the rest of the cell.36,65 Goldenbogen et al. observed that comparable dynamic changes in the biophysical properties of the cell wall occur in sexual reproduction during the formation of an elongated mating projection in response to mating pheromones. The newly formed projection contains a highly elastic cell wall, but the cell wall becomes increasingly stiff toward the tip of the projection.59 Characterization of cell wall composition in the bud and mating projection, as well as other morphological structures in budding yeast, attribute greater cell surface stiffness in part to increased concentrations of chitin, a linear ß-1–4-linked N-acetylglucosamine poly-saccharide.36,59,60,64–67 Mutants defective in chitin synthesis had a substantial reduction in cell wall stiffness, while altering other components, including ß-1–3-glucans or protein mannosylation, results in only modest changes to cell wall elasticity or no differences, respectively.64 In an interesting experimental synergy of AFM analysis with transcriptomics, Schiavone et al. found dramatic decreases in stiffness upon disruption of enzymes or signaling pathways that contribute to cross-linking the respective cell wall components, particularly mannoproteins, ß-1,3,-glucans, and chitin.64,68 This suggests that cross-linking and remodeling of the yeast cell wall, rather than varying the composition of the components incorporated, have greater impacts on the overall biophysical properties of the yeast cell wall.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of a yeast cell wall. Unlike bacterial cell walls, the main components of yeast cell walls are ß-glucan and chitin.

Measuring cell wall stiffness can also help elucidate the mechanism of antimicrobial compounds. Using the tetracyclic peptide duramycin, an antimicrobial peptide (AMP) that selectively targets only certain Gram-positive bacteria, Hasim et al. showed that Bacillus strains susceptible to duramycin have decreased cell wall stiffness after treatment.69 They conclude that duramycin is able to interfere with the cell wall stability only in susceptible strains, and that it is the disruption of cell wall integrity that produces a bacteriostatic effect in susceptible bacteria. We have recently found that the AMP magainin 2 (MAG2) is capable increasing the elasticity of the Gram-negative cell wall.24 MAG2 is capable of forming pores in lipid bilayers, and we may be observing the nanomechanical changes that occur as MAG2 forms pores in the Gram-negative outer membrane. Other AMPs may cause the cell wall to initially stiffen rather than become more elastic.70,71 Using a strain of the Gram-negative Klebsiella pneumoniae capable of excreting sugars to form a thick capsule as part of the cell wall, Mularski et al. exposed cells to a low dose of the AMP melittin and reported that the cell wall was significantly stiffer after treatment.70 However, over time the Young’s modulus decreased to the same value as untreated cells. When the authors measured the cell wall elasticity for a capsule deficient strain, the stiffness of the cell wall immediately decreased after treatment, indicating that an increase in cell wall stiffness could be a feature of the capsule rather than the entire cell wall. Treatment of the Gram-positive Bacillus subtillis (B. subtillis) with low doses of the AMP LL-37, the ceragenin CSA-13, or the ceragenin CSA-131 likewise resulted in stiffer cell walls than those observed in untreated cells. Again, the cell wall slowly became more elastic over time until the elasticity was similar to that of untreated cells.71 This time dependent change of bacterial cell wall stiffness in response to low concentrations of AMPs raises the interesting possibility that cell wall stiffening is a repair mechanism that can neutralize the effect of these antimicrobial compounds.

Like bacteria, yeast are highly adaptable to environmental changes, and force experiments have been used to characterize cellular responses to harmful extracellular stimuli or changes in membrane composition. AFM force experiments revealed that elasticity of the S. cerevisiae cell wall increases in response to ethanol stress or elevated osmotic pressure, while Pillet et al. found that prolonged exposure to heat stress can promote the formation of a stiff circular structure on the cell surface that is enriched in chitin.60,61,72 Furthermore, modifications to the cell wall with chemicals or synthetic polymers that alter cell wall stiffness or thickness can be assessed directly using AFM.56,73,74 As with bacteria, antifungal agents that target the yeast cell wall can dramatically alter the cell wall elasticity. The cell walls of S. cerevisiae and Candida albicans (C. albicans) both increased in stiffness after treatment with the antifungal caspofungin, though the effect was more pronounced in C. albicans.75 The increased stiffness observed in C. albicans correlated with an increase in the percent chitin composition of the cell wall, while no correlation was observed for S. cerevisiae. Further work implicated this increased presence of chitin, deposited in response to increasing caspofungin concentrations, in the development of antimicrobial resist-ance.76

The cell wall is not the only structure that can be evaluated using the nonlinear regime. When in its dormant state, the spore coat of some Bacillus species is the outermost cell surface and can be investigated as such.77,78 Bacillus cereus sporulation has been monitored by FD mapping across cells, revealing that the surface of the cell becomes more stiff where the spore forms, but becomes more elastic in the surrounding areas.77 The dormant Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis) spore is nearly 15-times stiffer than the vegetative cell, but during germination, the spore coat softens until the stiffness of the spore coat resembles that of a vegetative cell.78 The stiffness of the spore coat was then used to identify whether B. anthracis spores would undergo germination in response to different treatments. Further studies with the AMP chrysophsin-3 showed that, while other AMPs kill spores only after inducing germination, spores treated with chrysophsin-3 retained a stiff spore coat, indicating that cell death was not predicated on germination.79

The nonlinear regime can also provide information about the behavior of polymers on the cell surface.38 This is particularly interesting in Gram-negative bacteria, which may have long polysaccharide chains as part of the lipopolysaccharides (LPS) that constitute the outer leaflet of the outer membrane (Figure 6B). After analyzing the nonlinear region of force curves taken on different strains of E. coli, we were able to establish a correlation between the length of the nonlinear region and the length of the LPS.29 Strains that produced LPS lacking polysaccharide chains had a noticeably shorter nonlinear region. We have also demonstrated that fixing bacteria with N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS) and N-ethyl-N'-(3-diaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) caused the distance of the nonlinear region to decrease.29 We ascribed this shorter distance not to a physical change in the polymer length but due to off-target cross-linking of the polymers on the cell surface by NHS and EDC, creating a cage-like structure that restricts their interaction with the tip. Similar altered polymer behavior after cell fixation with glutaraldehyde has also been reported.21

The Alexander and de Gennes (AdG) model, which describes a polymer brush interacting with a surface, can be applied to describe both the thickness and density of cell surface polymers.37,80–84 Using E. coli strains with known biochemical differences in LPS composition, Strauss et al. applied the AdG model to measure LPS length, which they found to be closely correlated with cell adhesion.84 Expanding on the work with E. coli, Ivanov et al. genetically engineered P. aeruginosa mutants with altered LPS production and again used the AdG model to calculate the length and compressibility of the mutant LPS, correlating LPS length to other physical and biological properties of the bacteria.83 Using this model, changes in polymer condensation in response to solvent polarity, buffer conditions, and ionic strength have also been reported in various Gram-negative bacteria.80,81,85

Linear Compression: Measuring Turgor Pressure

The third regime of the approach curve, the linear compression, can be modeled as two springs pushing against each other, and the slope of this regime can be used to determine the spring constant of the cell, a measure of the cell’s stiffness (Figure 4).38 However, while the nonlinear regime reflects the stiffness or elasticity of the cell wall (vide supra), the cellular spring constant reflects the turgor pressure of the cell.35,72,86 When the ionic strength of the imaging buffer is increased, there is a corresponding decrease in the cellular spring constant, which demonstrates that the cellular spring constant reflects the cellular turgor pressure. Changing the environmental pH has also been shown to affect the cell stiffness.87

Cell stiffness can be a useful measurement of cell health. When microbial cells are healthy they maintain a fairly constant turgor pressure. However, when bacteria are treated with certain chemicals that interact with the cell membranes, the turgor pressure changes as the cell loses the ability to regulate osmosis. The AMP magainin 2 (MAG2) acts by forming pores in bacterial membranes, moving rapidly across the outer membrane to permeabilize the cell membrane.24 When E. coli were treated with MAG2, we observed a time-dependent decrease in cell stiffness. As pores were formed and stabilized in the outer and cell membranes, eventually the cell could no longer maintain its turgor pressure and collapsed, resulting in the cell stiffness decreasing by half. While investigating the effect of single walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT), Liu et al. also observed a time-dependent decrease in turgor pressure associated with the formation of SWCNT networks across the surface of the bacterium.88 They proposed that the SWCNT were piercing the cell, causing membrane disruption and leakage. However, when they used a sharpened AFM tip to model a single SWCNT piercing the cell, they observed no change in the cell stiffness, allowing them to conclude that network formation, rather than individual piercing events, is responsible for the observed decrease in turgor pressure. However, changing turgor pressure may not always be a sign of ill health. The cyanobacterium Anabaenopsis circularis glides across surfaces, and the cell stiffness changes depending on the gliding speed.89

Alternatively, bacteria have been reported to increase turgor pressure in response to changing environmental conditions. After exposure to hematite nanoparticles, Zhang et al. reported a cellular spring constant about 20-times higher than that of untreated E. coli.90 However, it is unclear whether this change represents a change in the cellular turgor pressure or if the nanoparticles coating the bacteria are contributing to the measured cell stiffness. Treatment with low levels of certain antibiotic compounds is also associated with an initial increase in turgor pressure, but the turgor pressure decreased over time, eventually matching the reported values for untreated cells.70,71 Increasing the turgor pressure of the cell could be a mechanism in which the cell controls and eliminates low levels of antibiotics. However, the stiffness of the cell wall also increased, and it is unclear how those two events are related.

Adhesion

Unlike cell stiffness and cell wall elasticity, adhesion is calculated from the retraction curve. As the cantilever is raised from the surface, adhesive elements on the surface pull against it, and the AFM must counter those forces as it raises the cantilever. The adhesive force on the cantilever appears as a negative value in the retraction curve, and when the adhesive force is overcome, the cantilever snaps up and the force rapidly increases, eventually returning to zero (Figure 5). The adhesive forces between the cantilever and the surface can release in a single event, resulting in a single inverted peak in the retraction curve, or over multiple events, producing multiple inverted peaks and giving the retraction curve a sawtoothed appearance. The change in force associated with each peak indicates how strong the adhesion was while the change in distance provides an indication of how far the cantilever was from the surface when the adhesion broke.

In bacteria, adhesive forces are generated from attractive interactions with the cell wall, from EPS excreted by some strains during the process of biofilm development, or from adhesion of a surface appendage such as a pilus or fimbria (Table 1). Several studies have investigated the intrinsic adhesive properties of bacteria. We previously examined the adhesion of biofilm-forming bacteria and compared the values to those obtained from a strain of E. coli that was not considered a traditional biofilm-former, but was cultured to encourage growth on a surface.29 Surprisingly, all of the bacteria had similar adhesion profiles, which we ascribed to the growth conditions allowing even a nontraditional biofilm-former to grow as a biofilm and produce EPS. Using eight strains of Listeria monocytogenes, Eskhan and Abu-Lail used AFM to investigate the differences in adhesion between clinical and environmental strains, finding that environmental strains had significantly higher adhesion to the silicon-nitride tip than the clinical strains and that the biopolymer behavior at the surface was different.91 Atabek and Camesano explored the relative contributions of both LPS and EPS to the adhesion of a P. aeruginosa strain and a related mutant with altered LPS structure and charge.92 They found that the adhesion forces were similar between the two strains, but adhesion events occurred over shorter distances in the mutant strain. However, the adhesion events for both strains occurred over distances too long to be LPS alone, so they concluded that EPS must be the determining factor in these adhesion events. Later work in the Camesano laboratory using mutants of Pseudomonas florescens showed that mutants lacking the LapA gene were two-times less adhesive than the wild-type, but mutants that could not remove the LapA protein from the cell surface were twice as adhesive, providing direct evidence that the LapA protein is an adhesin located on the cell surface.93

Table 1.

Summary of Bacterial Adhesion Forces

| bacteria | location of bacteria | adhesion | ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | surface, cantilever | Highly variable adhesion forces that depend on the binding partner. Reported values range from <0.1 nN to >9 nN. | 29, 99–102, 107 |

| Micrococcus luteus | surface | Reported average adhesion forces of 1 ± 0.6 nN between the bacterium and silicon nitride. | 29 |

| Pseudomonas putida | surface | Reported average adhesion forces of 0.7 ± 0.3 nN between the bacterium and silicon nitride. | 29 |

| Bacillus subtills | surface | Variable adhesion forces between the bacterium and silicon nitride probe. Reported values fall between 0.3 nN and 0.8 nN. | 29, 102 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | surface | Adhesion reported for eight strains with silicon nitride probe. Average adhesion values range from 0.10 to 0.22 nN. | 91 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | surface, cantilever | Reported average adhesion forces fall between 0.2 nN (pili alone) and 1 nN (whole cells). | 92, 105 |

| Pseudomonas florescens | surface | Average adhesion of the wild-type bacterium with silicon nitride is ∼0.5 nN, while various mutants have higher or lower adhesion. | 93 |

| Streptococcus mutans | cantilever | Average adhesion of the wild-type bacterium with silicon nitride is between 0.5 and 1 nN, while various mutants have higher or lower adhesion. | 94, 95 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | surface, cantilever | Average adhesion between the bacterium and fibrinogen is ∼2 nN, regardless of bacterial position on the surface or cantilever. | 96 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | surface, cantilever | Average adhesion between the bacterium and von Willebrand factor is ∼2 nN, regardless of bacterial position on the surface or cantilever. | 97, 98 |

| Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans | surface | Adhesion forces between planktonic cells and a mineral probe are ∼0.15 nN, while adhesion forces between biofilm cells and a mineral probe are ∼0.5 nN. | 103 |

The Dufrene laboratory has been using AFM to investigate the molecular mechanisms of adhesion in Gram-positive bacteria for many years, providing direct evidence for the importance of individual proteins in bacteria adhesion. Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is a Gram-positive, cavity-causing bacterium that can also cause endocarditis if it enters the bloodstream.94 Its adhesion is mediated by the cell surface protein P1. Using purified P1 attached to the tip and its binding partner, salivary agglutinin, coating the surface, Sullen et al. found only weak adhesion between the two proteins. However, when they attached a cell to the tip, they observed much larger adhesion forces and concluded that adhesion was achieved by the binding of multiple P1 proteins at the same time, highlighting the importance of investigating adhesion in a cellular context. Further research, now using antibodies that recognize different parts of the P1 structure tethered to the cantilever, showed that P1 does not form ordered domains at the cell surface but does form a higher order structure of P1 derived polypeptides interacting with a P1 covalently attached to the surface of the cell.95

Unlike P1, purified SdrG, the protein responsible for Staphylococcus epidermidis adhesion, binds robustly to surfaces covered in its binding partner, fibrinogen.96 When the system is flipped and the tip is coated with fibrinogen, force mapping revealed the formation of SdrG domains on the cell surface. In more recent work, Viela et al. showed that adhesion by S. aureus to von Willebrand factor (vWF), a glycoprotein found on the surface of endothelial cells, is controlled by a force-dependent mechanism.97 Using cells attached to the cantilever, they probed both a surface coated with vWF and endothelial cells, which revealed extremely strong adhesion forces that increased as the cell was pulled away from the surface. These adhesion events were absent in S. aureus mutants lacking the surface protein SpA. The authors proposed that the increased adhesion is potentially due to conformation changes in the vWF that reveals additional SpA binding sites. Further research showed that inactivation of the ArlRS-MgrA signaling pathway led to decreased adhesion to both surfaces coated with relevant biomolecules and endothelial cells, likely by the expression of large surface proteins that shielded smaller surface proteins from their binding partners.98

Altered cellular adhesion in response to environmental changes have also been explored. Liu et al. exposed E. coli associated with severe urinary tract infections to commercially available cranberry juice cocktail and observed a significant decrease in adhesion after a three-hour treatment.99 The decrease in adhesion was reversible; cells incubated in cranberry juice then rinsed and returned to growth media had identical adhesion profiles to cells that were not exposed to cranberry juice. They proposed that a compound in cranberry juice is altering the adhesins responsible for bacterial attachment. Later work demonstrated that the ΔG of adhesion between bacteria and uroepithelial cells was unfavorable in the presence of cranberry juice and, now attaching the bacteria to the cantilever, directly probed the adhesion between the two cells, demonstrating that it was lower in the presence of metabolized cranberry juice.100,101 Unlike cranberry juice, ampicillin increases the adhesion between bacteria and the AFM tip. Treatment with ampicillin at the minimum inhibitory concentration for B. subtilis or E. coli increased adhesion, though the result was more pronounced for B. subtilis than E. coli.102

Changing the chemical makeup of the cantilever or the surface can also provide valuable adhesion data. Li et al. used cantilevers with tips made of pyrite or chalcopyrite and FD mapping to quantify the adhesion of Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans planktonic and biofilm cells, mimicking mineral leaching that can occur in mines.103 Xu et al. grew a biofilm of E. coli on a tipless cantilever and monitored the adhesion to chemically diverse surfaces.104 They observed distinct force profiles for each surface tested and detected adhesion events in some systems after only a few seconds. However, the adhesion profiles changed upon addition of a nonhydrolyzable mannose analogue, which inhibits the protein FimH found on type I pili. The biofilm cells had less adhesion to the surfaces, highlighting the important role of type I pili in biofilm adhesion by this strain of E. coli. To investigate the response of P. aeruginosa type IV pili to mechanical stress, Beaussart et al. first investigated the adhesion of the pili to a hydrophobic tip, finding that the pili were highly adhesive, more so than when a hydrophilic tip was used.105 Using the tip to generate an upward force, the authors revealed that the pili can withstand pulling forces up to 250 pN, which highlights the important role type IV pili play in P. aeruginosa adhesion under physiological conditions. The retraction curves contained several distinct force plateaus, which the authors argue reflects the specific conformation changes that occur as the pili are pulled upward. Further experiments, in which a single bacterium was attached to a colloidal probe and lowered to the surface of a lung cell, demonstrated that the observed nanoscale behaviors of the type IV pili were critical to colonization of a host.

It is possible to probe the interaction of specific molecules with the microbial surface by attaching the molecule of interest to the tip. Using lectin from P. aeruginosa and concanavalin A tethered to the tip, Francius et al. used FD mapping to determine the conformation, distribution, and adhesion of individual polysaccharides on the surface of the probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG.106 Using these functionalized probes, they were able to see clear differences in the polysaccharide compliment of the wild-type and that of an adhesion-deficient mutant. Rather than identifying molecules on the surface, Strauss et al. used bacteria with known surface components and created a functionalized tip with the AMP cecropin P1 (CP1) to investigate the binding interaction between the two.107 They found that LPS length had a direct correlation to the strength of the binding; longer LPS produced a stronger adhesion. However, they also determined that bactericidal action by CP1 was dependent not on binding strength but on how CP1 was attached to the substrate.

AFM with functionalized cantilevers has also provided valuable insight into a variety of yeast cell surface properties including mapping surface hydrophobicity, characterizing macromolecular interactions, and measuring fluctuations in membrane thickness. Tips covalently modified with concanavalin A lectins were used to map the distribution and adhesion properties of mannan oligosaccharides associated with cell surface mannoproteins in two Saccharomyces strains (S. cerevisiae and S. carlsbergensis).65 This analysis revealed the S. cerevisiae surface mannoproteins to be more extended and elastic relative to the those in S. carlsbergensis, despite these two strains having similar cell wall compositions. High-resolution mapping of surface protein distribution has been achieved in yeast by probing for adhesion between His-tagged cell surface proteins and functionalized Ni2+-NTA tips, which can provide insight into microdomains or areas of protein concentration not resolvable in live cells by conventional fluorescence microscopy. This approach was utilized by Alsteens et al. to characterize the enhanced localization of Mid2, a yeast membrane protein involved in sensing cell wall dynamics, in the bud scar during S. cerevisiae budding.44 Ni2+-NTA functionalized tips were also used by Dupres et al. in conjunction with His-tags bound to a variable length linker region on the extracellular side of the budding yeast transmembrane signaling protein Wsc1.56 This novel strategy provided a single molecule ruler for measuring cell wall thickness at 5 nm resolution, which they used to quantify degradation of a 10 nm outer layer of polysaccharides by the glucanase Zymolase and an over 40 nm thickening of the cell wall upon treatment with Diamide, a chemical known to cause oxidative stress in yeast.56

Functionalized probes have also provided valuable insights into cell wall changes and biofilm formation upon exposure to antimicrobial drugs. Adhesion experiments revealed that upon treatment with the antifungal Caspofungin, the fungal pathogen C. albicans undergoes dramatic cell wall structural changes leading to increased surface exposure of the adhesive signaling lectin Dectin-1, which promotes cell surface interactions with macrophage recognition proteins leading to enhanced pathogen recognition and immune response.67,108 Interestingly, El Kirat-Chatel et al. observed that Caspofungin treatment also led to increased cell surface exposure of the adhesin glycoprotein Als1, which triggers the formation of cellular aggregates and contributes to biofilm formation, perhaps acting as a protective counter-measure to antimicrobial action.108 Though AFM with functionalized cantilevers has been utilized for probing yeast cell wall biophysical properties over the past decade, examples of more widespread implementation in bacterial studies reveal the potential for expanding this approach into other areas of study, and makes it a powerful tool for yeast cell biologists and biochemists going forward.

Adhesion measurements can also provide insight into the contributions of individual members of bacterial communities. By attaching lactobacillus species often found in fermented dairy to a cantilever and probing their adhesion to various milk proteins, Burgain et al. identified specific interactions between the bacteria and whey proteins, which may be important in forming a dairy matrix during fermentation.109 Further research mapped the adhesion to pili and other biomolecules, but the source of the interaction was dependent on the strain and the environmental conditions, potentially explaining why different strains of lactobacillus produce different types of cheese.110,111 To investigate the difference in adhesiveness between single cells and communities, El-Kirat-Chatel et al. tested the ability of five species of marine bacteria to adhere to coatings used to prevent biofouling on the hulls of boats.112 They found that the bacteria that were the least adhesive as a community had high individual adhesion, illustrating that the behavior of a single bacterium is not always equivalent to that of a community. Using cantilevers coated with saliva to probe the adhesiveness of several bacterial species commonly found in the oral microbiome, Kristensen et al. observed decreased adhesion after exposure to the milk protein osteopontin.113 The decrease in adhesion was greater than that of other milk proteins that had been studied previously, suggesting that osteoprontin may be able to delay biofilm formation on teeth. Measuring the adhesion of bacteria with AFM can also provide insight to the behavior of bacterial communities on living tissue. Mittelviefhaus et al. measured the adhesion of various bacterial isolates from leaf microbiota, which correlated with the known retention of the bacteria to leaves in planta.114 The authors propose that the adhesion of these bacterial species may influence leaf colonization and could be manipulated to help with disease prevention or treatment.

CONCLUSION

While AFM has greatly illuminated the biomechanical properties of microbes, there is still much to be done. Advances in AFM that enhance the spatial and temporal resolution of imaging in combination with nanomechanical and adhesion characterization provide exciting opportunities for the expansion of AFM in the study of microbial cells. While high speed AFM has been primarily confined to imaging, eventually improvements to the technique could allow scientists to map changes to cellular biomechanics in close to real time.115 In bacteria, coupled AFM and fluorescent microscopy, along with mechanosensitive fluorescent probes, could allow for determination of individual protein contributions to cellular behavior under mechanical stress.116 Combined with genetic manipulation, AFM can also provide further insights to the cell-cell interactions that take place as part of biofilm formation or human disease.117 In yeast, the expansion of correlated fluorescence-atomic force microscopy can contribute to a better understanding of how local nanomechanical properties are shaped by the subcellular localization of cell wall synthases or cross-linking enzymes.118 Additionally, AFM experiments could provide new insights into cell wall dynamics and remodeling during polarized growth, enhance characterization of rapid cellular responses to environmental changes, and enable better tracking of biophysical changes during the cellular life cycle through time-course experiments.

Regardless of the coming advances in AFM, current AFM techniques still have much to offer biomaterials research. The microbial response to biomaterials remains an important field of research with untapped potential. From the hulls of boats to artificial joints, colonization of surfaces by microbes can lead to serious consequences.119 To prevent damage, understanding the microprocesses that contribute to adhesion can illuminate surface properties that repel microbes. Novel ways of preventing or treating microbial infections can be investigated using AFM force measurements, leading to better treatments in a world that is currently losing a battle with antibiotic resistant bacteria.120 The mechanisms used by new antifungal or antibacterial compounds can be elucidated by monitoring the changes in microbial biomechanics, and current treatments can be redesigned to become more effective. Using AFM, in combination with other techniques, we can truly begin to understand life at the nanoscale.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Binnig G; Quate C; Gerber C Atomic Force Microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 56 (9), 930–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Radmacher M; Tillamnn R; Fritz M; Gaub H From Molecules to Cells: Imaging Soft Samples with the Atomic Force Microscope. Science 1992, 257 (5078), 1900–1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Dufrne YF Atomic Force Microscopy,a Powerful Tool in Microbiology. J. Bacteriol. 2002, 184 (19), 5205–5213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Horber J;Miles M Scanning Probe Evolution in Biology. Science 2003, 302 (5647), 1002–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Alessandrini A; Facci P AFM: A Versatile Tool in Biophysics. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2005, 16 (6), R65–R92. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Dufrêne YF; Ando T; Garcia R; Alsteens D;Martinez-Martin D; Engel A; Gerber C; Müller DJ Imaging Modes of Atomic Force Microscopy for Application in Molecular and Cell Biology. Nat. Nanotechnol 2017, 12 (4), 295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Amarouch M; Hilaly J; Mazouzi D AFM and FluidFM Technologies: Recent Applications in Molecular and Cellular Biology. Scanning 2018, 2018,1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Martin Y; Williams C; Wickramasinghe H Atomic Force Microscope-Force Mapping and Profiling on a Sub 100-Å Scale. J. Appl. Phys. 1987, 61 (10), 4723–4729. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hansma P; Cleveland J; Radmacher M; Walters D; Hillner P; Bezanilla M; Fritz M; Vie D; Hansma H; Prater C; et al. Tapping Mode Atomic Force Microscopy in Liquids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1994, 64 (13), 1738–1740. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Putman CA; der Werf KO; Grooth BG; Hulst NF; Greve J Tapping Mode Atomic Force Microscopy in Liquid. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1994, 64 (18), 2454–2456. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Drake B; Prater C; Weisenhorn A; Gould S; Albrecht T; Quate C; Cannell D; Hansma H; Hansma P Imaging Crystals, Polymers, and Processes in Water with the Atomic Force Microscope. Science 1989, 243 (4898), 1586–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Schaeffer TE; Viani M; Walters DA; Drake B; Runge EK; Cleveland JP; Wendman MA; Hansma PK Atomic Force Microscope for Small Cantilevers. Proc. SPIE 1997, 3009,48–52. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Ando T Directly Watching Biomolecules in Action by High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy. Biophys. Rev 2017, 9 (4), 421–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Kasas S; Dietler G DNA-Protein Interactions Explored by Atomic Force Microscopy. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 73, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Kim K High-Resolution Imaging of the Microbial Cell Surface. J. Microbiol. 2016, 54 (11), 703–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Viji Babu PK; Radmacher M Mechanics of Brain Tissues Studied by Atomic Force Microscopy: A Perspective. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13,1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Norregaard K; Metzler R; Ritter CM; Berg-Sørensen K; Oddershede LB Manipulation and Motion of Organelles and Single Molecules in Living Cells. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117 (5), 4342–4375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Gross L; Mohn F; Moll N; Liljeroth P; Meyer G The Chemical Structure of a Molecule Resolved by Atomic Force Microscopy. Science 2009, 325 (5944), 1110–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Xu L; Lio A; Hu J; Ogletree FD; Salmeron M Wetting and Capillary Phenomena of Water on Mica. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102 (3), 540–548. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gavara N A Beginner’s Guide to Atomic Force Microscopy Probing for Cell Mechanics. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2017, 80 (1), 75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Vadillo-Rodríguez V; Busscher HJ; Norde W; Vries J; Dijkstra RJ; Stokroos I; Mei HC Comparison of Atomic Force Microscopy Interaction Forces between Bacteria and Silicon Nitride Substrata for Three Commonly Used Immobilization Methods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70 (9), 5441–S446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Liu Y; Camesano TA; Camesano TA; Mello CM Immobilizing Bacteria for Atomic Force Microscopy Imaging or Force Measurements in Liquids. Microbial Surfaces 2008, 984, 163–188. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Mazia Dj Schatten G; Sale W Adhesion of Cells to Surfaces Coated with Polylysine. Applications to Electron Microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 1975, 66 (l), 198–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Voile C; Overton K; Greer H; Ferguson M; Spain E; Elmore Dj Núñez M Measuring the Effect of Antimicrobial Peptides on the Biophysical Properties of Bacteria Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Biophys. J. 2018, 114 (3), 354a. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Anderson G; O’Toole G; Romeo T Innate and Induced Resistance Mechanisms of Bacterial Biofilms. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008, 322, 85–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Flemming H-C; Wingender J The Biofilm Matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8 (9), 623–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Verstrepen KJ; Klis FM Flocculation, Adhesion and Biofilm Formation in Yeasts. Mol. Microbiol. 2006, 60 (l), 5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Váchová L; Palková Z How Structured Yeast Multicellular Communities Live, Age and Die. FEMS Yeast Res. 2018, 18 (4), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Voile C; Ferguson M; Aidala K; Spain E; Núñez M Spring Constants and Adhesive Properties of Native Bacterial Biofilm Cells Measured by Atomic Force Microscopy. Colloids Surf, B 2008, 67 (l), 32–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).De T; Chettoor AM; Agarwal P; Salapaka MV; Nettikadan S Immobilization Method of Yeast Cells for Intermittent Contact Mode Imaging Using the Atomic Force Microscope. Ultramicroscopy 2010, 110 (3), 254–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Kasas S; Ikai A A Method for Anchoring Round Shaped Cells for Atomic Force Microscope Imaging. Biophys. J. 1995, 68 (5), 1678–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Formosa C; Pillet F; Schiavone M; Duval RE; Ressier L; Dague E Generation of Living Cell Arrays for Atomic Force Microscopy Studies. Nat. Protoc 2015, 10 (l), 199–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hutter JL; Bechhoefer J Calibration of Atomic-force Microscope Tips. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1993, 64 (7), 1868–1873. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Mathelie-Guinlet M; Viela F; Vijloen A; Dehullu J; Dufrene YF Single-Molecule Atomic Force Microscopy Studies of Microbial Pathogens. Curr. Opin Biomed Eng 2019, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Voile CB; Ferguson MA; Aidala KE; Spain EM; Núñez ME Quantitative Changes in the Elasticity and Adhesive Properties of Escherichia coli ZK1056 Prey Cells During Predation by Bdellovibriobacteriovorus 109J. Langmuir 2008, 24 (15), 8102–8110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Touhami A; Nysten B; Dufrêne YF Nanoscale Mapping of the Elasticity of Microbial Cells by Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir 2003, 19 (11), 4539–4543. [Google Scholar]

- (37).O’Connor S; Gaddis R; Anderson E; Camesano TA; Burnham NA A High Throughput MATLAB Program for Automated Force-Curve Processing Using the AdG Polymer Model. J. Microbiol. Methods 2015, 109, 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Velegol SB; Logan BE Contributions of Bacterial Surface Polymers, Electrostatics, and Cell Elasticity to the Shape of AFM Force Curves. Langmuir 2002, 18 (13), 5256–5262. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Radmacher M; Cleveland JP; Fritz M; Hansma HG; Hansma PK Mapping Interaction Forces with the Atomic Force Microscope. Biophys. J. 1994, 66 (6), 2159–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Heinz WF; Hoh JH Spatially Resolved Force Spectroscopy of Biological Surfaces Using the Atomic Force Microscope. Trends Biotechnol. 1999, 17 (4), 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Viani M; Schaffer T; Paloczi G; Pietrasanta L; Smith B; Thompson J; Rchter M; Ref M; Gaub H; Plaxco K; Cleland A; Hansma H; Hansma P Fast Imaging and Fast Force Spectroscopy of Single Biopolymers with a New Atomic Force Microscope Designed for Small Cantilevers. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1999, 70 (11), 4300–4303. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Ando T; Kodera N; Takai E; Maruyama D; Saito K; Toda A A High-Speed Atomic Force Microscope for Studying Biological Macromolecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98 (22), 12468–12472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Sahin O; Magonov S; Su C; Quate CF; Solgaard O An Atomic Force Microscope Tip Designed to Measure Time-Varying Nanomechanical Forces. Nat. Nanotechnol 2007, 2 (8), 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Alsteens D; Dupres V; Yunus S; Latgé JP;Heinisch JJ; Dufrêne YF High-Resolution Imaging of Chemical and Biological Sites on Living Cells Using Peak Force Tapping Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir 2012, 28 (49), 16738–16744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Dufrêne YF; Martínez-Martín D; Medalsy I; Alsteens D; Müller DJ Multiparametric Imaging of Biological Systems by Force-Distance Curve-Based AFM. Nat. Methods 2013, 10 (9), 847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Chopinet L; Formosa C; Rols MP; Duval RE; Dague E Imaging Living Cells Surface and Quantifying Its Properties at High Resolution Using AFM in QI™ Mode. Micron 2013, 48,26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Yang Q; Ma Q; Herum KM; Wang C; Patel N; Lee J; Wang S; Yen TM; Wang J; Tang H; Lo Y; Head B; Azam F; Xu S; Cauwenberghs G; McCulloch A; John S; Liu Z; Lal R Array Atomic Force Microscopy for Real-Time Multiparametric Analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116 (13), 201813518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Camesano TA; Logan BE Probing Bacterial Electrosteric Interactions Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34 (16), 3354–3362. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Silhavy TJ; Kahne D; Walker S The Bacterial Cell Envelope. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol 2010, 2 (5), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Mathelié-Guinlet M; Grauby-Heywang C; Martin A; Fevrier H; Moroté F; Vilquin A; Beven L; Delville MH; Cohen-Bouhacina, T. Detrimental Impact of Silica Nanoparticles on the Nanomechanical Properties of Escherichia coli Studied by AFM. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 529,53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Formosa C; Grare M; Duval RE; Dague E Nanoscale Effects of Antibiotics on P. aeruginosa. Nanomedicine 2012, 8 (1), 12–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Gaveau A; Coetsier C; Roques C; Bacchin P; Dague E; Causserand C Bacteria Transfer by Deformation through Micro-filtration Membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 523, 446–455. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Francius G; Domenech O; Mingeot-Leclercq M; Dufrêne YF Direct Observation of Staphylococcus aureus Cell Wall Digestion by Lysostaphin. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190 (24), 7904–7909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Loskill P; Pereira PM; Jung P; Bischoff M; Herrmann M; Pinho MG; Jacobs K Reduction of the Peptidoglycan Crosslinking Causes a Decrease in Stiffness of the Staphylococcus aureus Cell Envelope. Biophys. J. 2014, 107 (5), 1082–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Osumi M Visualization of Yeast Cells by Electron Microscopy. Microscopy 2012, 61 (6), 343–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Dupres V; Dufrêne YF; Heinisch JJ Measuring Cell Wall Thickness in Living Yeast Cells Using Single Molecular Rulers. ACS Nano 2010, 4 (9), 5498–5504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Aguilar-Uscanga B; François JM A Study of the Yeast Cell Wall Composition and Structure in Response to Growth Conditions and Mode of Cultivation. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 37 (3), 268–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Lesage G; Bussey H Cell Wall Assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Mol. Biol. R 2006, 70 (2), 317–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Goldenbogen B; Giese W; Hemmen M; Uhlendorf J; Herrmann A; Klipp E Dynamics of Cell Wall Elasticity Pattern Shapes the Cell during Yeast Mating Morphogenesis. Open Biol. 2016, 6 (9), 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Pillet F; Lemonier S; Schiavone M; Formosa C; Martin-Yken H; Francois J; Dague E Uncovering by Atomic Force Microscopy of an Original Circular Structure at the Yeast Cell Surface in Response to Heat Shock. BMC Biol 2014, 12 (1), 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Schiavone M; Formosa-Dague C; Elsztein C; Teste M-A; Martin-Yken H; Morais MA; Dague E; François JM Evidence for a Role for the Plasma Membrane in the Nanomechanical Properties of the Cell Wall as Revealed by an Atomic Force Microscopy Study of the Response of Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Ethanol Stress. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82 (15), 4789–4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Ahimou F; Touhami A; Dufrêne YF Real-Time Imaging of the Surface Topography of Living Yeast Cells by Atomic Force Microscopy. Yeast 2003, 20 (1), 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Bui V; Kim Y; Choi S Physical Characteri Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Surf. Interface Anal. 2008, 40 (10), 1323–1327. [Google Scholar]

- (64).Dague E; Bitar R; Ranchon H; Durand F; Yken H; François JM An Atomic Force Microscopy Analysis of Yeast Mutants Defective in Cell Wall Architecture. Yeast 2010, 27 (8), 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Alsteens D; Dupres V; Evoy K; Wildling L; Gruber HJ; Dufrêne YF Structure, Cell Wall Elasticity and Polysaccharide Properties of Living Yeast Cells, as Probed by AFM. Nanotechnology 2008, 19 (38), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).DeMarini DJ; Adams A; Fares H; Virgilio C; Valle G; Chuang JS; Pringle JR A Septin-Based Hierarchy of Proteins Required for Localized Deposition of Chitin in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Cell Wall. J. Cell Biol. 1997, 139 (1), 75–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Hasim S; Allison DP; Retterer ST; Hopke A; Wheeler RT; Doktycz MJ; Reynolds TB ß-(1,3)-Glucan Unmasking in Some Candida albicans Mutants Correlates with Increases in Cell Wall Surface Roughness and Decreases in Cell Wall Elasticity. Infect. Immun. 2017, 85 (1), No. e00601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Schiavone M; Déjean S; Sieczkowski N; Castex M; Dague E; Francois JM Integration of Biochemical, Biophysical and Transcriptomics Data for Investigating the Structural and Nanomechanical Properties of the Yeast Cell Wall. Front. Microbiol 2017, 8,1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Hasim S; Allison DP; Mendez B; Farmer AT; Pelletier DA; Retterer ST; Campagna SR; Reynolds TB; Doktycz MJ Elucidating Duramycin’s Bacterial Selectivity and Mode of Action on the Bacterial Cell Envelope. Front. Microbiol 2018, 9,1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Mularski A; Wilksch JJ; Wang H; Hossain MA; Wade JD; Separovic F; Strugnell RA; Gee ML Atomic Force Microscopy Reveals the Mechanobiology of Lytic Peptide Action on Bacteria. Langmuir 2015, 31 (22), 6164–6171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Pogoda K; Piktel E; Deptula P; Savage PB; Lekka M; Bucki R Stiffening of Bacteria Cells as a First Manifestation of Bactericidal Attack. Micron 2017, 101,95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Arfsten J; Leupold S; Bradtmöller C; Kampen I; Kwade A Atomic Force Microscopy Studies on the Nanomechanical Properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Colloids Surf., B 2010, 79 (1), 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Suchodolskis A; Feiza V; Stirke A; Timonina A Ramanaviciene, A.; Ramanavicius, A. Elastic Properties of Chemically Modified Baker’s Yeast Cells Studied by AFM. Surf. Interface Anal. 2011, 43 (13), 1636–1640. [Google Scholar]

- (74).Andriukonis E; Stirke A; Garbaras A; Mikoliunaite L; Ramanaviciene A; Remeikis V; Thornton B; Ramanavicius A Yeast-Assisted Synthesis of Polypyrrole: Quantification and Influence on the Mechanical Properties of the Cell Wall. Colloids Surf., B 2018, 164, 224–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Formosa C; Schiavone M; Martin-Yken H; François J; Duval R; Dague E Nanoscale Effects of Caspofungin against Two Yeast Species, Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57 (8), 3498–3506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Quiles F; Accoceberry I; Couzigou C; Francius G; Noël T; El-Kirat-Chatel S AFM Combined to ATR-FTIR Reveals Candida Cell Wall Changes under Caspofungin Treatment. Nanoscale 2017, 9 (36), 13731–13738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Wang C; Stanciu C; Ehrhardt CJ; Yadavalli VK Morphological and Mechanical Imaging of Bacillus cereus Spore Formation at the Nanoscale. J. Microsc. 2015, 258 (1), 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Pinzón-Arango PA; Nagarajan R; Camesano TA Effects of L-Alanine and Inosine Germinants on the Elasticity of Bacillus anthracis Spores. Langmuir 2010, 26 (9), 6535–6541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Pinzón-Arango PA; Nagarajan R; Camesano TA Interactions of Antimicrobial Peptide Chrysophsin-3 with Bacillus anthracis in Sporulated, Germinated, and Vegetative States. J. Phys. Chem. B 2013, 117 (21), 6364–6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Abu-Lail NI; Camesano TA Role of Lipopolysaccharides in the Adhesion, Retention, and Transport of Escherichia coli JM109. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37 (10), 2173–2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Abu-Lail NI; Camesano TA The Effect of Solvent Polarity on the Molecular Surface Properties and Adhesion of Escherichia coli. Colloids Surf., B 2006, 51 (1), 62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Emerson RJ; Camesano TA Nanoscale Investigation of Pathogenic Microbial Adhesion to a Biomaterial. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70 (10), 6012–6022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Ivanov IE; Kintz EN; Porter LA; Goldberg JB; Burnham NA; Camesano TA Relating the Physical Properties of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Lipopolysaccharides to Virulence by Atomic Force Microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193 (5), 1259–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Strauss J; Burnham NA; Camesano TA Atomic Force Microscopy Study of the Role of LPS O-antigen on Adhesion of E. coli. J. Mol. Recognit. 2009, 22 (5), 347–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Abu-Lail NI; Camesano TA Role of Ionic Strength on the Relationship of Biopolymer Conformation, DLVO Contributions, and Steric Interactions to Bioadhesion of Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Biomacromolecules 2003, 4 (4), 1000–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Arnoldi M; Fritz M; Bäuerlein E;Radmacher M; Sackmann E; Boulbitch A Bacterial Turgor Pressure Can Be Measured by Atomic Force Microscopy. Phys. Rev. E: Stat. Phys., Plasmas, Fluids, Relat. Interdiscip. Top. 2000, 62 (1), 1034–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Gaboriaud F; Bailet S; Dague E; Jorand F Surface Structure and Nanomechanical Properties of Shewanellaputrefaciens Bacteria at Two PH Values (4 and 10) Determined by Atomic Force Microscopy. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187 (11), 3864–3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Liu S; Ng A; Xu R; Wei J; Tan C; Yang Y; Chen Y Antibacterial Action of Dispersed Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes on Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis Investigated by Atomic Force Microscopy. Nanoscale 2010, 2 (12), 2744–2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Dhahri S; Ramonda M; Marliére C In-Situ Determination of the Mechanical Properties of Gliding or Non-Motile Bacteria by Atomic Force Microscopy under Physiological Conditions without Immobilization. PLoS One 2013, 8 (4), 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Zhang W; Hughes J; Chen Y Impacts of Hematite Nanoparticle Exposure on Biomechanical, Adhesive, and Surface Electrical Properties of Escherichia coli Cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78 (11), 3905–3915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Eskhan AO; Abu-Lail NI Cellular and Molecular Investigations of the Adhesion and Mechanics of Listeria monocytogenes Lineages’ I and II Environmental and Epidemic Strains. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013, 394, 554–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Atabek A; Camesano TA Atomic Force Microscopy Study of the Effect of Lipopolysaccharides and Extracellular Polymers on Adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2007, 189 (23), 8503–8509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Ivanov IE; Boyd CD; Newell PD; Schwartz ME; Turnbull L; Johnson MS; Whitchurch CB; O’Toole GA; Camesano TA Atomic Force and Super-Resolution Microscopy Support a Role for LapA as a Cell-Surface Biofilm Adhesin of Pseudomonas fluorescens. Res. Microbiol. 2012, 163 (9–10), 685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Sullan RA; Li JK; Crowley PJ; Brady JL; Dufrêne YF Binding Forces of Streptococcus mutans P1 Adhesin. ACS Nano 2015, 9 (2), 1448–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Heim KP; Sullan RA; Crowley PJ; El-Kirat-Chatel S; Beaussart A; Tang W; Besingi R; Dufrene YF; Brady JL Identification of a Supramolecular Functional Architecture of Streptococcus mutans Adhesin P1 on the Bacterial Cell Surface. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290 (14), 9002–9019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Herman P; El-Kirat-Chatel S; Beaussart A; Geoghegan JA; Foster TJ; Dufrêne YF The Binding Force of the Staphylococcal Adhesin SdrG Is Remarkably Strong. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 93 (2), 356–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Viela F; Prystopiuk V; Leprince A; Mahillon J; Speziale P; Pietrocola G; Dufrêne YF Binding of Staphylococcus aureus Protein A to von Willebrand Factor Is Regulated by Mechanical Force. mBio 2019, 10 (2), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Kwiecinski JM; Crosby HA; Valotteau C; Hippensteel JA; Nayak MK; Chauhan AK; Schmidt EP; Dufrene YF; Horswill AR Staphylococcus aureus Adhesion in Endovascular Infections Is Controlled by the ArlRS—MgrA Signaling Cascade. PLoS Pathog 2019, 15 (5), 1–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Liu Y; Black MA; Caron L; Camesano TA Role of Cranberry Juice on Molecular-scale Surface Characteristics and Adhesion Behavior of Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bio eng 2006, 93 (2), 297–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Liu Y; Gallardo-Moreno AM; Pinzon-Arango PA; Reynolds Y; Rodriguez G; Camesano TA Cranberry Changes the Physicochemical Surface Properties of E. coli and Adhesion with Uroepithelial Cells. Colloids Surf., B 2008, 65 (l), 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Liu Y; Pinzón-Arango PA; Gallardo-Moreno AM; Camesano TA Direct Adhesion Force Measurements between E. coli and Human Uroepithelial Cells in Cranberry Juice Cocktail. Mol. Nutr. Food Res 2010, 54 (12), 1744–1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Laskowski Dj Strzelecki J; Pawlak Kj Dahm H; Balter A Effect of Ampicillin on Adhesive Properties of Bacteria Examined by Atomic Force Microscopy. Micron 2018, 112, 84–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Li Q; Becker T; Zhang R; Xiao T; Sand W Investigation on Adhesion of Sulfobacillusthermosulfidooxidans via Atomic Force Microscopy Equipped with Mineral Probes. Colloids Surf., B 2019, 173, 639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Xu H; Murdaugh AE; Chen W; Aidala KE; Ferguson MA; Spain E; Núñez ME Characterizing Pilus-Mediated Adhesion of Biofilm-Forming E. coli to Chemically Diverse Surfaces Using Atomic Force Microscopy. Langmuir 2013, 29 (9), 3000–3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Beaussart A; Baker AE; Kuchma SL; El-Kirat-Chatel S; O’Toole GA; Dufrene YF Nanoscale Adhesion Forces of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Type IV Pili. ACS Nano 2014, 8 (10), 10723–10733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Francius G; Lebeer S; Alsteens D; Wildling L; Gruber HJ; Hols P; Keersmaecker S; Vanderleyden J; Dufrêne YF Detection, Localization, and Conformational Analysis of Single Polysaccharide Molecules on Live Bacteria. ACS Nano 2008, 2 (9), 1921–1929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Strauss J; Kadilak A; Cronin C; Mello CM; Camesano TA Binding, Inactivation, and Adhesion Forces between Antimicrobial Peptide Cecropin PI and Pathogenic E. coli. Colloids Surf., B 2010, 75 (l), 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).El-Kirat-Chatel S; Beaussart A; Alsteens D; Jackson DN; Lipke PN; Dufrêne YF Nanoscale Analysis of CaspofunginInduced Cell Surface Remodelling in Candida albicans. Nanoscale 2013, 5 (3), 1105–1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Burgain J; Gaiani C; Francius G; Revol-Junelles AM; Cailliez-Grimal C; Lebeer S; Tytgat HLP; Vanderleyden J; Scher J In Vitro Interactions between Probiotic Bacteria and Milk Proteins Probed by Atomic Force Microscopy. Colloids Surf, B 2013, 104, 153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Guerin J; Burgain J; Francius G; El-Kirat-Chatel S; Beaussart A; Scher J; Gaiani C Adhesion of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG Surface Biomolecules to Milk Proteins. Food Hydrocolloids 2018, 82, 296–303. [Google Scholar]

- (111).Gomand F; Borges F; Guerin J; El-Kirat-Chatel S; Francius G; Dumas D; Burgain J; Gaiani C Adhesive Interactions Between Lactic Acid Bacteria and β-Lactoglobulin: Specificity and Impact on Bacterial Location in Whey Protein Isolate. Front. Microbiol 2019, 10, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (112).El-Kirat-Chatel S; Puymege A; Duong TH; Overtvelt P; Bressy C; Belec L; Dufrêne YF; Molmeret M Phenotypic Heterogeneity in Attachment of Marine Bacteria Toward Antifouling Copolymers Unraveled by AFM. Front. Microbiol 2017, 8, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (113).Kristensen M; Zeng G; Neu T; Meyer R; Baelum V; Schlafer S Osteopontin Adsorption to Gram-Positive Cells Reduces Adhesion Forces and Attachment to Surfaces Under Flow. J. Oral Microbiol 2017, 9 (l), 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (114).Mittelviefhaus M; Muller DB; Zambelli T; Vorholt JA A Modular Atomic Force Microscopy Approach Reveals a Large Range of Hydrophobic Adhesion Forces among Bacterial Members of the Leaf Microbiota. ISME J 2019, 13 (7), 1878–1882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (115).Heath GR; Scheuring S Advances in High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy (HS-AFM) Reveal Dynamics of Transmembrane Channels and Transporters. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 57, 93–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]