Abstract

Reactive oxygen species induced by ionizing radiation and metabolic pathways generate 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (oxoG) and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine (oxoA) as two major forms of oxidative damage. The mutagenicity of oxoG, which promotes G to T transversions, is attributed to the lesion’s conformational flexibility that enables Hoogsteen base pairing with dATP in the confines of DNA polymerases. The mutagenesis mechanism of oxoA, which preferentially causes A to C transversions, remains poorly characterized. While structures for oxoA bypass by human DNA polymerases are available, that of prokaryotic DNA polymerases have not been reported. Herein, we report kinetic and structural characterizations of Sulfolobus solfataricus Dpo4 incorporating a nucleotide opposite oxoA. Our kinetic studies show oxoA at the templating position reduces the replication fidelity by ~560-fold. The catalytic efficiency of the oxoA:dGTP insertion is ~300-fold greater than that of the dA:dGTP insertion, highlighting the promutagenic nature of oxoA. The relative efficiency of the oxoA:dGTP misincorporation is ~5-fold greater than that of the oxoG:dATP misincorporation, suggesting the mutagenicity of oxoA is comparable to that of oxoG. In the Dpo4 replicating base pair site, oxoA in the anti-conformation forms a Watson-Crick base pair with an incoming dTTP, while oxoA in the syn-conformation assumes Hoogsteen base pairing with an incoming dGTP, displaying the dual coding potential of the lesion. Within the Dpo4 active site, the oxoA:dGTP base pair adopts a Watson-Crick-like geometry, indicating Dpo4 influences the oxoA:dGTP base pair conformation. Overall, the results reported here provide insights into the miscoding properties of the major oxidative adenine lesion during translesion synthesis.

INTRODUCTION

Reactive oxygen species, which are produced by ionizing radiation, aerobic respiration, and normal cellular metabolism, are proficient in oxidative modification of biological molecules including lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids [1]. In particular, the attack of reactive oxygen species (e.g., hydroxyl radical) on DNA generates 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (oxoG) and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine (oxoA) as two major oxidative lesions (Figure 1A) [2, 3]. Elevated cellular levels of oxoG are associated with the development of neurodegenerative diseases, aging, and cardiovascular diseases [4, 5].

Figure 1. Base pairing properties of oxoG and oxoA in the absence/presence of protein contacts.

(A) The syn- and anti-conformations of oxoA. (B) Hoogsteen base pairing between syn-oxoG and anti-dA. Note that oxoG:A adopts a Watson-Crick-like geometry. (C) Hoogsteen base pairing between syn-oxoA and anti-dG. Note that oxoA:G base pair assumes a wobble geometry. (D) Hoogsteen base pairing between oxoA:dGTP in the active site of Polη. Gln38 of Polη engages in minor groove interactions with both syn-oxoA and anti-dGTP. (E) Hoogsteen base pairing of oxoA:dGTP in the active site of Polβ. Asn279 and Arg283 of Polβ make minor groove contacts to anti-dG and syn-oxoA, respectively. OxoA:dGTP shows a Watson-Crick-like base pair geometry in the confines of Polβ active site.

The base pair geometry of syn-oxoG:anti-dA is essentially identical to that of the correct base pair; this facilitates the formation of the promutagenic oxoG:A base pair in the active site of DNA polymerases (Figure 1B) [6–8], thus promoting G to T transversions [4]. OxoA, the cellular levels of which are up to one half of those of oxoG [9, 10], is a major oxidative DNA modification found in γ-irradiated DNA and the genomes of human cancerous tissues [9, 11, 12]. Unlike oxoG, which favors a Watson-Crick-like base pair with dA, oxoA engages in a wobble base pair with dG (Figure 1C), where N7-H and O8 of syn-oxoA are hydrogen bonded to O6 and N1-H of anti-dG, respectively [13]. While oxoA is significantly less mutagenic than oxoG in E. coli cells [14], the same lesion induces a significant number of A to C mutations in mammalian cells [3, 15, 16], suggesting differential mutagenicity of oxoA in prokaryotic and mammalian cells. OxoA opposite thymine is cleaved by E. coli mismatch-specific uracil DNA glycosylase (MUG) and human thymine DNA glycosylase (TDG) [3, 17–19].

The oxoA lesion bypass by high fidelity DNA polymerases in prokaryotes (e.g., Taq DNA polymerase and Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I) takes place in an error-free manner [20, 21]. In contrast, mammalian DNA polymerases α and β frequently misincorporate dGTP and dCTP opposite the lesion in vitro [15]. The presence of oxoA at the templating position decreases the replication fidelity of human Polη by ~100-fold [22, 23], highlighting the promutagenic properties of oxoA. Structural studies show that the minor groove contact by Gln38 of Polη stabilizes the base pairing between syn-oxoA and anti-dGTP, thereby promoting dGTP insertion opposite oxoA. Currently, the oxoA lesion bypass by prokaryotic Y-family DNA polymerases has not been reported and is the focus of the present study.

Dpo4 from Sulfolobus solfataricus is an archaeal DNA polymerase that displays high homology to Y-family human DNA polymerases, Polη and Polκ. Due to its structural similarities to these polymerases, Dpo4 has been frequently used as a model system for studying the lesion bypass properties of Y-family DNA polymerases. Dpo4 has a spacious, solvent-accessible active site that can accommodate structurally diverse lesions including cisplatin-GG intrastrand cross-links [24], benzo[a]pyrene [25], O6-methylguanine [26], abasic sites [27], ethenoguanine [28], and oxoG [29]. Previous kinetic and structural studies have provided key insights into the lesion bypass and fidelity mechanisms of Dpo4 [30–34].

Here, we report steady-state kinetic studies of Dpo4 incorporating dTTP and dGTP opposite the major oxidative adenine lesion oxoA. We also present two crystal structures of ternary complexes of Dpo4 in complex with incoming nonhydrolyzable dTTP and dGTP analogs opposite templating oxoA. These structures highlight the conformational flexibility and miscoding properties of oxoA in the catalytic site of Dpo4. These results provide new insights into the dual coding potential of the major oxidative adenine lesion and its mechanisms of mutagenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein expression, crystallization and structure determination.

Dpo4 was overexpressed and purified from E. coli using protocols described previously [28]. Ternary Dpo4 complexes with a templating oxoA and an incoming nonhydrolyzable dNTP analog were prepared and crystallized using minor modifications of published crystallization conditions [30]. To obtain ternary Dpo4-DNA complexes, Dpo4 was first incubated with a recessed DNA duplex containing a 18-mer template (5′-TCAT[oxoA]GAATCCTTCCCCC-3′) and a complementary 13-mer primer (5′-GGGGGAAGGATTC-3′), producing a Dpo4-DNA binary complex. Subsequently, a 10-fold molar excess of nonhydrolyzable dGMPNPP or dTMPNPP (Jena Bioscience) was added to the binary complex. The resulting ternary Dpo4-DNA complexes were crystalized in a buffer solution containing 50 mM Tris pH 7.5, 16–25% PEG3350, and 100 mM magnesium acetate. The ternary complex crystals were cryoprotected in the mother liquor supplemented with 15% ethylene glycol and were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected at 100 K at the beamline 19-ID at the Advanced Photon Source and at the beamline BL 5.0.1. at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. All diffraction data were processed using HKL2000. Structures were solved by molecular replacement with a ternary Dpo4 complex structure (PDB ID: 1JX4) as a search model using Molrep [35]. The molecular model was built using COOT [36], and was refined using PHENIX [37]. MolProbity was used to make Ramachandran plots [38]. All the crystallographic figures were generated using Chimera [39].

Steady-state kinetics of single nucleotide incorporation opposite templating oxoA by Dpo4.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for Dpo4-catalyzed nucleotide insertion opposite templating oxoA were measured as similarly described previously [23, 40]. Briefly, 5´-FAM-labeled primer (5´-FAM/GGGGGAAGG ATTC-3´) and oxoA-modified template (5´-TCAT(oxoA)GAATCCTTCCCCC-3´) were annealed in a hybridization buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA) by heating at 90°C for 5 min and slowly cooling to room temperature. Enzyme activities were determined using the reaction mixture containing 40 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 60 mM KCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 250 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 2.5% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 nM annealed DNA, and varying concentration of an individual dNTP. To prevent the end-product inhibition and substrate depletion, the enzyme concentrations and reaction-time intervals were adjusted for each experiment (less than 20% insertion product formed). Nucleotide insertion reactions were initiated by adding the enzyme and stopped by adding a gel-loading buffer (95% formamide with 20 mM EDTA, 45 mM Tris-borate, 0.1% bromophenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol). The quenched reaction mixtures were separated on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. The gels were analyzed using ImageQuant (GE Healthcare) to quantify the nucleotide insertion products. The kcat and Km were determined by fitting reaction rate over dNTP concentrations to the Michaelis-Menten equation. Each experiment was repeated three times to determine the average and the standard deviation of the kinetic results. The efficiency of nucleotide insertion was calculated as kcat/Km. The relative efficiency of dGTP misincorporation opposite oxoA was determined as f = (kcat/Km) [dGTP:oxoA] /(kcat/Km) [dTTP:oxoA].

RESULTS

Translesion synthesis of the major oxidative adenine damage by Dpo4 is promutagenic.

To evaluate the miscoding properties of oxoA lesion, we determined steady-state kinetic parameters for Dpo4 incorporating a nucleotide (dTTP or dGTP) opposite a templating dA or oxoA (Table 1). Dpo4 inserted dTTP opposite oxoA with a relative efficiency of 0.55 (16.1×10−3 s−1μM−1 vs. 8.9×10−3 s−1μM−1, Table 1 and Figure 2), indicating that the presence of oxoA in the Dpo4 catalytic site does not significantly affect correct insertion by the enzyme. Specifically, substituting dA for oxoA negligibly changed Km (5.2 vs. 4.6 μM) and decreased kcat by only 2-fold (82.9×10−3 s−1 vs. 40.3×10−3 s−1). The templating oxoA, however, greatly facilitated misincorporation by Dpo4. The catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) for the oxoA:dGTP insertion was ~300-fold (0.002 vs. 0.64) greater than that for the dA:dGTP insertion. Furthermore, replacing the templating dA with oxoA decreased the fidelity ~560-fold (7800 vs. 14), demonstrating that the major oxidative adenine lesion within the Dpo4 active site greatly promotes mutagenic replication.

Table 1.

Steady-state kinetic parameters for nucleotide incorporation opposite oxoA and dA by Dpo4.

| template:dNTP | Km (μM) | kcat (10−3s−1) | kcat/Km (10−3s−1μM−1) | fa | replication fidelity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| dA:dTTP | 5.2 ±0.3 | 82.9 ±2.2 | 16.1 | 1 | 7800 |

| dA:dGTP | 454.1 ±6.5 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 0.002 | 0.00013 | |

| oxoA:dTTP | 4.6 ±0.4 | 40.3 ±1.5 | 8.9 | 1 | 14 |

| oxoA:dGTP | 33.6 ±2.4 | 21.3 ±0.5 | 0.64 | 0.072 | |

| dG:dCTPb | 1.96 ±0.4 | 46.67 ±5.0 | 23.81 | 1 | 14100 |

| dG:dATPb | 2860 ±300 | 4.83 ±0.33 | 0.0017 | 0.000071 | |

| oxoG:dCTPb | 1.6 ±0.4 | 20.00 ±3.33 | 12.5 | 1 | 70 |

| oxoG:dATPb | 180 ±40 | 31.67 ±3.33 | 0.176 | 0.014 |

Relative efficiency:(kcat/Km)[dNTP:dA]/(kcat/Km)[dTTP:dA] or (kcat/Km)[dNTP:oxoA]/(kcat/Km)[dTTP:oxoA]

Reference [28]

Figure 2. Representative denaturing PAGE gels for Dpo4 incorporating nucleotide opposite oxoA.

Insertion of dTTP (A) or dGTP (B) opposite oxoA by Dpo4. An annealed DNA of 5´-FAM-labeled primer and an oxoA-modified template was mixed with varying concentrations of dTTP or dGTP, and the reactions were initiated by the addition of Dpo4. All the reactions were conducted at 37 °C, and the quenched reaction samples were separated on 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gels.

OxoA forms a Watson-Crick base pair with an incoming dTTP* in the active site of Dpo4.

Our steady-state kinetic studies show Dpo4 efficiently incorporates dTTP opposite a templating oxoA. To gain structural insights into how this occurs, we solved a ternary complex structure of Dpo4 incorporating a nonhydrolyzable dTMPNPP (dTTP* hereafter) opposite a templating oxoA in the presence Mg2+ ions. The nonhydrolyzable nucleotide dTTP* was used because it is isosteric to dTTP, and its coordination to the active-site metal ions is virtually indistinguishable from that of dTTP. The nonhydrolyzable dNTP analogs have been frequently used in the determination of ternary structures of various DNA polymerases [41, 42]. The Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* ternary complex was crystallized in the P21 space group with cell dimensions of a = 52.84 Å, b = 97.46 Å, c = 101.24 Å, α = 90.00°, β = 90.05°, and γ = 90.00°. The Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* ternary structure was refined to a resolution of 2.84 Å with Rwork = 23.0% and Rfree = 28.0% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics.

| PDB code | oxoA:T (6VGM) | oxoA:G (6VG6) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Collection | ||

| space group | P21 | P21 |

| Cell Constants | ||

| a (Å) | 52.835 | 52.975 |

| b | 97.459 | 97.761 |

| c | 101.237 | 101.815 |

| α (°) | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β | 90.05 | 89.99 |

| γ | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| resolution (Å)a | 50.00–2.84 (2.89–2.84) | 50.00–3.08 (3.14–3.08) |

| Rmergeb (%) | 0.075 (0.725) | 0.059 (0.461) |

| <I/σ> | 15.9 (1.1) | 10.2 (1.1) |

| CC1/2 | 0.394 | 0.486 |

| completeness (%) | 98.5 (98.0) | 98.6 (96.9) |

| redundancy | 3.4 (3.2) | 3.3 (2.8) |

| Refinement | ||

| Rworkc/Rfreed (%) | 23.0/28.0 | 25.6/30.3 |

| unique reflections | 23992 | 20219 |

| Mean B Factor (Å2) | ||

| protein | 75.37 | 69.67 |

| ligand | 53.59 | 74.97 |

| solvent | 63.41 | 54.23 |

| Ramachandran Plot | ||

| most favored (%) | 94.7 | 98.5 |

| add. allowed (%) | 5.0 | 1.5 |

| RMSD | ||

| bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.004 |

| bond angles (degree) | 0.881 | 0.753 |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge = Σ|I-<I>|/ ΣI where I is the integrated intensity of a given reflection.

Rwork = Σ|F(obs)-F(calc)|/ΣF(obs).

Rfree = Σ|F(obs)-F(calc)|/ΣF(obs), calculated using 5% of the data.

The Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* ternary complex structure provides the structural basis for the correct insertion past oxoA by the enzyme (Figure 3). The ternary structure displays the conserved secondary structures and the four characteristic domains (thumb, palm, finger, and little finger) of Y-family DNA polymerases (Figure 3A). The oxoA:dTTP* base pair is well accommodated within the enzyme’s catalytic site (Figure 3B). The strong electron density around anti-oxoA and the incoming dTTP* indicates oxoA:dTTP* is ordered in the replicating base pair site of Dpo4. The guanidinium moieties of Arg331 and Arg332 engage in hydrogen bond interactions with the 5’-phosphate oxygens and the 8-oxo group of oxoA, respectively, thereby stabilizing oxoA at the templating position (Figure 3C). On the other hand, the side chains of Tyr48 and Arg51 are hydrogen bonded to the phosphate oxygens of the incoming dTTP*. The templating oxoA adopts an anti-conformation and forms a Watson-Crick base pair with dTTP* at inter-base hydrogen bonding distances of 2.7 Å and 3.0 Å (Figure 3D). The base pair geometry of oxoA:dTTP* is essentially identical to that of the canonical base pair. Specifically, oxoA:dTTP* base pair displays the λ angles of 49° (oxoA) and 59° (dTTP*) and a C1´-C1´ distance of 10.5 Å (Figure 3D). The similar oxoA:dTTP* base pair conformations have been observed in published polβ and polη structures [22, 23]. The primer terminus 3´-OH is coordinated to the A-site magnesium ion and is about 4.4 Å away from the Pα of the incoming dTTP* (Figure 3E), poised for in-line nucleophilic attack on the Pα of the incoming nucleotide. The A- and B-site magnesium ions are coordinated with ligands including Asp7, Phe8, Asp105, Glu106, phosphate oxygens, and primer terminus 3´-OH (Figure 3E). In addition, dTTP* stacks with the primer terminus dT (Figure 3E). Overall, the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* ternary complex structure containing two metal ions and exhibiting Watson-Crick base pairing is consistent with the efficient dTTP incorporation opposite oxoA by the enzyme.

Figure 3. Ternary complex structure of Dpo4 incorporating dTTP* opposite oxoA lesion.

(A) Overall structure of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* ternary complex. The templating oxoA and incoming dTTP* are colored in magenta and yellow, respectively. (B) Close-up view of the replicating base pair site of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* ternary complex structure. A 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 1σ around oxoA and dTTP* is shown. OxoA is in an anti-conformation and forms a Watson-Crick base pair with dTTP*. The magnesium ions are shown in green spheres. (C) Interactions of oxoA:dTTP* with the catalytic site residues of Dpo4. Hydrogen bonds are shown in dashed lines. (D) Base pairing properties of anti-oxoA and dTTP*. The hydrogen bond distances, C1´-C1´ distance and λ angles for oxoA:dTTP* base pair are shown. (E) Coordination of Mg2+ ions in Dpo4 catalytic site. The distance between the nucleophilic 3´-OH of primer terminus and the Pα of incoming dTTP* is indicated as a double headed arrow.

Comparison of published Dpo4 ternary structures with our oxoA:dTTP* structures reveals the impact of the templating oxoA on the DNA conformation (Figure 4). While the nascent base pairs of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* and published Dpo4-dG:dCTP structures adopt a canonical Watson-Crick conformation, DNA conformations at the N+1 and N+2 positions of these structures significantly differ (Figure 4A and 4B). Unlike the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* structure, in the Dpo4-dG:dCTP structure, Arg332 does not form a hydrogen bond with the 5´-phosphate oxygen of the templating base. Similar conformations for Arg331 and Arg332 are observed in the published Dpo4-oxoG:dCTP* structure [43], where Arg331 and Arg332 are hydrogen bonded to the 5´-phosphate and the 8-oxo moiety of oxoG, respectively. These results indicate Arg332 may play a role in accommodating 8-oxopurine at the templating position [43]. Despite the similar conformations for Arg331 and Arg332 in the oxoA:dTTP* and oxoG:dCTP* structures, their DNA conformations at the N+1 and N+2 positions show a large deviation (Figure 4C and 4D).

Figure 4. Comparison of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* structure with published Dpo4-dG:dCTP and Dpo4-oxoG:dCTP* structures.

(A) Overlay of the active sites of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* (multiple colors) and Dpo4-dG:dCTP-Ca2+ (pdb: 2ATL; white color) structures. Conformations of Tyr48, Arg51, Arg331 and Arg332 are shown. (B) The catalytic site of the published Dpo4-dG:dCTP structure with Ca2+ ions (PDB code: 2ATL). (C) Overlay of the active sites of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* (multiple colors) and the Dpo4–oxoG:dCTP* (2XCP, single color) structures. (D) The catalytic site of published Dpo4-oxoG:dCTP*-Mg2+ structure (PDB code: 2XCP). Note Arg331 and Arg332 engage in hydrogen bonding interaction with 5´-phosphate of oxoG.

OxoA forms a Watson-Crick-like base pair with dGTP* in the active site of Dpo4.

Our steady-state kinetic analysis shows substituting dA for oxoA at the templating position greatly (~560-fold) promotes mutagenic replication (Table 1). To gain structural insights into the promutagenic nature of oxoA in the active site of Dpo4, we determined the ternary structure of Dpo4 in complex with the templating oxoA and incoming dGTP*. The ternary complex of Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* was crystallized in P21 space group with cell dimensions of a = 52.98 Å, b = 97.76 Å, c = 101.82 Å, α = 90.00° , β = 89.99, and γ = 90.00°. The Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* structure was refined to a resolution of 3.08 Å with Rwork = 25.6% and Rfree = 30.3% (Table 2).

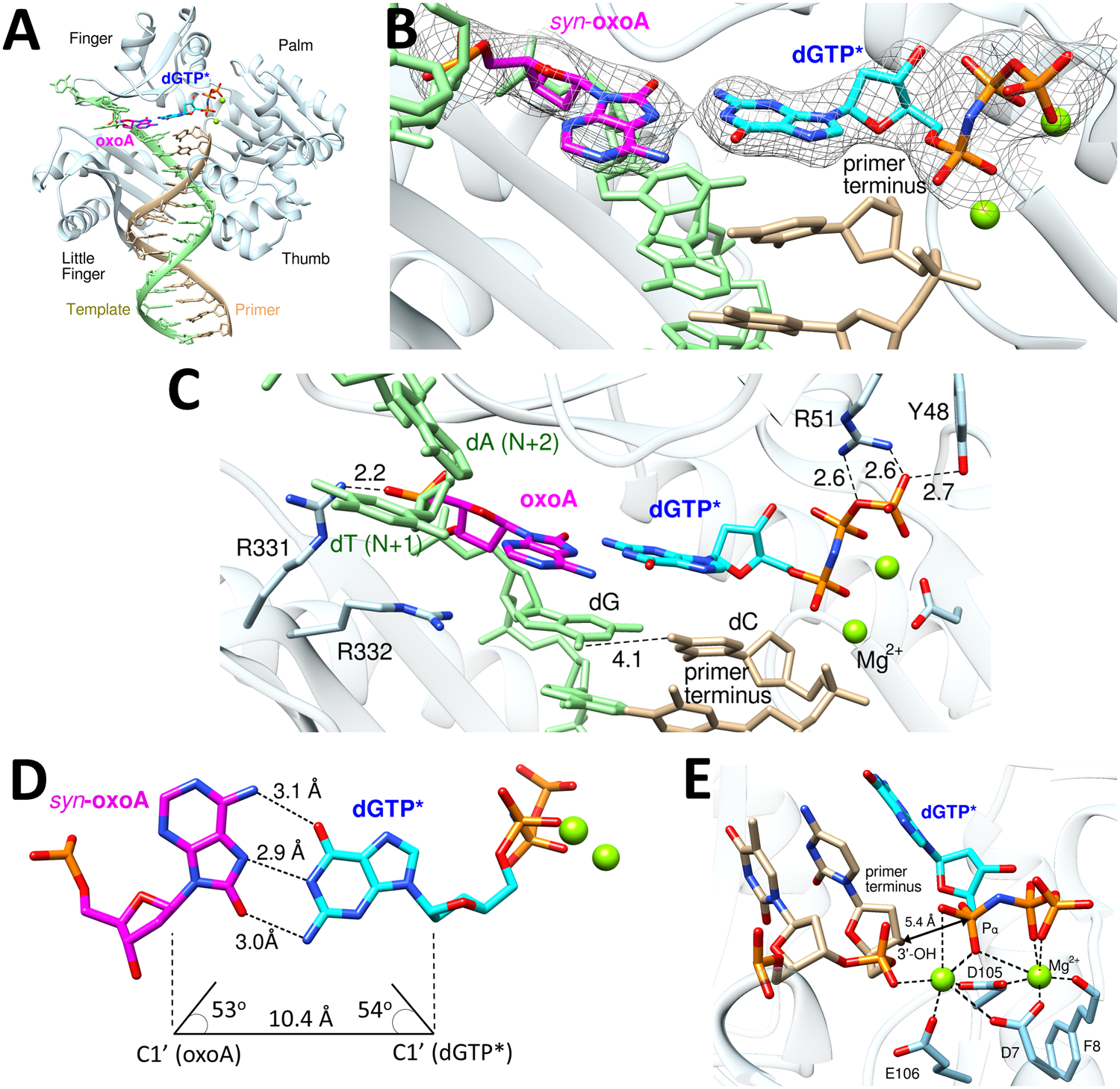

The Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* ternary complex structure reveals the promutagenic properties of oxoA in the Dpo4 active site (Figure 5). The overall structure of the oxoA:dGTP* structure is very similar to that of the oxoA:dTTP* structure (RMSD = 0.29 Å). In the replicating base pair site of Dpo4, oxoA is in a syn-conformation and the incoming dGTP* is in an anti-conformation (Figure 5B). Both A- and B-site metal ions are present in the catalytic site. Arg332 no longer engages in hydrogen bond interactions with oxoA, while Arg331 remains hydrogen bonded to the 5´-phosphate oxygen of the templating oxoA (Figure 5C). Unlike the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* structure, the primer terminus G:C base pair in the oxoA:dGTP* structure does not form Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds despite its correct base pairing, suggesting oxoA:dGTP affects the conformation of the primer terminus base pair. Interestingly, oxoA and dGTP* form three Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds with a Watson-Crick-like geometry (Figure 5D). The inter-base hydrogen bonding distances for oxoA:dGTP* are 3.0 Å, 2.9 Å, and 3.1 Å. The λ angles for oxoA:dGTP* are 53° (oxoA) and 54° (dGTP*). The C1´ (oxoA)-C1´ (dGTP*) distance is 10.4 Å. Therefore, the base pair geometry for oxoA:dGTP* is virtually identical to that observed in correct base pairs.

Figure 5. Ternary complex structure of Dpo4 incorporating dGTP* opposite templating oxoA lesion.

(A) Overall structure of the Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* ternary complex. OxoA and incoming dGTP* are colored in magenta and cyan, respectively. (B) Close-up view of the replicating base pair site of the Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* ternary complex structure. A 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 1σ around oxoA and dGTP* is shown. OxoA is in a syn-conformation and forms a Watson-Crick-like base pair with the incoming dGTP*. Mg2+ cofactors are shown in green spheres. (C) Interaction of the oxoA:dGTP* base pair with amino acid residues of the Dpo4 active site. Hydrogen bonds are indicated as dashed lines. (D) Base pair geometry for syn-oxoA and incoming dGTP*. (E) Coordination of the active-site Mg2+ ions. The distance between the nucleophilic 3´-OH of primer terminus and the Pα of incoming dGTP* is indicated as a double headed arrow.

The coordination of the A-site magnesium ion is significantly different from those observed in Dpo4 structures catalyzing the correct insertion (Figure 5E). Specifically, the primer terminus 3´-OH is not coordinated to the A-site Mg2+ ion and is about 5.4 Å away from the Pα of the incoming dGTP*. In addition, the primer terminus 3´-OH points away from the Pα and thus is not optimally positioned for in-line nucleophilic attack on the Pα. The lack of coordination of the primer terminus 3´-OH appears to be caused by a relatively large propeller-twist angle (20°) for oxoA:dGTP*. The presence of two purine rings (syn-oxoA and dGTP*) at the N position could influence the conformation of the primer terminus base pair, possibly inducing an unfavorable alignment of 3´-OH for nucleotidyl transfer reaction. Our kinetic studies show that the catalytic efficiency of the oxoA:dGTP insertion is ~320-fold greater than that of the dA:dGTP insertion, while it is ~14-fold less than that of the oxoA:dTTP insertion (Table 2). Overall, the Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* ternary complex structure with a Watson-Crick-like oxoA:dGTP* base pair conformation but non-optimal orientation of the 3´-OH primer terminus is consistent with our kinetic data.

Structural comparison of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* and Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* complexes.

The comparison of the Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* and Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* structures provide insights into the difference in the catalytic efficiency of the oxoA:dGTP and oxoA:dTTP insertions. In Dpo4 catalytic site, dTTP insertion opposite oxoA is 14-fold more efficient than dGTP insertion opposite oxoA. The superposition of the oxoA:dGTP* and oxoA:dTTP* structures reveals large conformational changes of DNA at the N+1 and N+2 positions (Figure 6A). In particular, the templating dT at the N+1 position stacks with anti-oxoA in the oxoA:dTTP* structure, while it is flipped out of the helix in the oxoA:dGTP* structure. The lack of the stacking interaction between the templating oxoA and dT (N+1) in during the oxoA:dGTP insertion could result in an increased Km. The geometry of the oxoA:dTTP* and oxoA:dGTP* base pairs in the Dpo4 active site are much alike (Figure 6B), indicating both base pairs are well tolerated in the nascent base pair site of Dpo4. OxoA:dTTP with Watson-Crick geometry can occur through their major tautomers. On the contrary, oxoA:dGTP with Watson-Crick-like geometry requires either of the nucleobases to undergo tautomerization in the replicating base pair site. Such requirement would make the oxoA:dGTP insertion less favorable than the oxoA:dTTP. One notable conformational difference is found in Arg332 of Dpo4 (Figure 6C), which is positioned near the template DNA. In the oxoA:dTTP* structure, Arg332 is hydrogen bonded to the 5´-phophate oxygen and O8 of the templating oxoA at the N position. In the presence of the incoming dGTP*, Arg332 moves toward the templating base at the N-1 position and thus no longer engages in hydrogen bonding interactions with the oxoA nucleotide. Overall, the comparison of the Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* and Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* structures highlights that both base pairs are readily accommodated in the Dpo4 active site without triggering large-scale conformational changes of protein.

Figure 6. Comparison of the oxoA:dTTP* and oxoA:dGTP* base pairs in Dpo4.

(A) Overlay of the replicating base pair sites of the oxoA:dTTP* and oxoA:dGTP* structures. (B) A top view of the overlay of the oxoA:dTTP* and oxoA:dGTP* base pairs. (C) A side view of the overlay of the oxoA:dTTP* and oxoA:dGTP* base pairs.

DISCUSSION

While the base pairing properties of oxoA:dTTP* in the catalytic sites of DNA polymerases are essentially the same (Figure 7A and 7B), those of oxoA:dGTP* vary significantly among DNA polymerases. In the absence of protein contact, oxoA:dG forms two Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds with a wobble geometry. In the confines of the X-family Polβ, the oxoA:dGTP* forms three Hoogsteen hydrogen bonds with a Watson-Crick-like geometry. The formation of Watson-Crick-like oxoA:dGTP* base pair in Polβ active site may be induced by the minor groove contact by Asn279, which is hydrogen bonded to the N3 of dGTP. The minor groove interaction would lower the pKa of oxoA and dGTP, thereby increasing the population of the rare enol tautomer of oxoA or dGTP. The involvement of the rare enol tautomer of oxoA or dGTP will allow to form Watson-Crick-like oxoA:dGTP conformation. Abrogation of the minor groove interaction via an Asn279Ala mutation results in the adoption of syn-oxoA:syn-dGTP base pair conformation. In the active site of human Y-family Polη, oxoA:dGTP* takes on a wobble geometry (Figure 7C), which is greatly stabilized by Gln38-mediated minor groove contacts to both oxoA and dGTP. The conformational differences of oxoA:dGTP in the active sites of Polβ and Polη suggest that the minor groove interaction is not the sole determining factor for Watson-Crick-like oxoA:dGTP conformation. In the catalytic site of prokaryotic Y-family DNA polymerase Dpo4, oxoA:dGTP does not engage in minor groove interaction with protein, yet it takes on a Watson-Crick-like conformation, indicating that the microenvironment of Dpo4 promotes the formation of Watson-Crick-like oxoA:dGTP conformation. The active site of Dpo4, which is more spacious than that of Polβ and Polη, might be more suitable for accepting Watson-Crick-like oxoA:dGTP conformation in the absence of the minor groove contacts to the nascent base pair.

Figure 7. Structural comparison of Dpo4 and polη inserting dTTP and dGTP opposite templating oxoA.

(A) Crystal structure of polη-oxoA:dTTP* complex. (B) Superposition of structures of Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP* and polη-oxoA:dTTP* (PDB ID: 6PL8) structures. Polη structure is shown in gray and Dpo4 in multiple colors. (C) Crystal structure of the polη-oxoA:dGTP* complex. Minor groove interactions by Gln38 are indicated as dashed lines. (D) Superposition of the Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* (multiple colors) and polη-oxoA:dGTP* (gray) structures.

The bypass of the major oxidative adenine lesion by Dpo4 and Polη is more error prone than that of the major oxidative guanine lesion. Dpo4 incorporates dCTP (correct nucleotide) opposite oxoG 70-fold more efficiently than dGTP [44]. On the other hand, the same enzyme inserts dTTP (correct nucleotide) opposite oxoA only 14-fold more efficiently than dGTP, indicating that oxoA is more promutagenic than oxoG. The catalytic efficiency of the correct insertion opposite oxoA is comparable to that of the correct insertion opposite oxoG [44]. The catalytic efficiency for the incorrect oxoA:dGTP insertion, however, is ~4-fold greater than that of the incorrect oxoG:dATP insertion. The lower catalytic efficiency for the oxoG:dATP insertion is mainly caused by a higher Km. In addition to Dpo4, human Polη replicates past oxoA ~2-fold less accurately than oxoG, highlighting the promutagenic nature of oxoA.

The structural comparison of the Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP and Polη-oxoA:dGTP complexes provide insights into the differences in the oxoA bypass fidelity of these polymerases. The replication fidelity of oxoA bypass by Solfolobus solfataricus Dpo4 is ~7-fold greater than that by human Polη [23]. This difference in fidelity is caused by the decrease in the catalytic efficiency of the oxoA:dGTP insertion by Dpo4 relative to Polη. The oxoA:dGTP insertion efficiency of Polη is ~8-fold greater than that of Dpo4. The high misincorporation rate for Polη is mainly due to a lower Km value compared to Dpo4. The crystal structure of Polη-oxoA:dGTP* reveals that Gln38 of Polη stabilizes the binding of dGTP at the replicating base pair site by making minor groove contacts to both the templating oxoA and incoming dGTP (Figure 7D). The removal of the minor groove interactions by Gln38Ala Polη increases the Km by ~20-fold [22], illustrating the role of the minor groove interaction in the oxoA:dGTP insertion. In contrast, the corresponding position where Gln38 of polη is located is occupied by a hydrophobic residue (Val32) in Dpo4, precluding minor groove hydrogen bonding interactions with oxoA:dGTP. In addition, while the 3´-OH of primer terminus dT in the Polη-oxoA:dGTP* structure is optimally positioned for in-line nucleophilic attack, the corresponding 3´-OH in the Dpo4-oxoA:dGTP* structure is in a non-optimal position for the nucleotidyl transfer reaction, which would slow incorporation of dGTP opposite oxoA. Overall, these structural differences may contribute to the observed differences in the replication fidelities of oxoA bypass by Dpo4 and Polη.

CONCLUSION

Here, our kinetic and structural characterizations of the Dpo4-mediated bypass of oxoA provides insights into the miscoding potential of the major oxidative adenine lesion. The dGTP incorporation opposite oxoA by Dpo4 is ~320-fold more efficient than that opposite dA. The substitution of a templating dA for oxoA reduces the fidelity by ~560-fold, suggesting that oxoA promotes mutagenic replication by translesion synthesis DNA polymerases. In the catalytic site of Dpo4, oxoA adopts an anti conformation when paired with an incoming dTTP* and a syn conformation when paired with an incoming dGTP*, highlighting the conformational flexibility of oxoA in the templating position. Interestingly, the oxoA:dGTP base pair adopts a Watson-Crick-like geometry, indicating the promutagenic oxoA:dGTP base pair is well tolerated within the catalytic site of Dpo4. The relative efficiency of the oxoA:dGTP insertion by Dpo4 is ~5-fold greater than that of the oxoG:dATP insertion, indicating the oxoA lesion bypass by some TLS polymerases is more error-prone than the oxoG lesion bypass. In sum, these findings presented here further our understanding of the promutagenic nature of oxoA and the bypass of oxoA in prokaryotes by a translesion synthesis polymerase.

Acknowledgements:

We are grateful to Dr. Arthur Monzingo for technical assistance. Instrumentation and technical assistance for this work were provided by the Macromolecular Crystallography Facility, with financial support from the College of Natural Sciences, the Office of the Executive Vice President and Provost, and the Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology at the University of Texas at Austin. Portions of this research were conducted at the Advanced Photon Source with the support of GM/CA. GM/CA@APS has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002) and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM-12006). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The Elger 16M detector was funded by an NIH-Office of Research Infrastructure Programs, High-End Instrumentation Grant (1S10OD012289-01A1).

Funding: This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (ES 26676).

Footnotes

Accession Numbers: The atomic coordinates of Dpo4-DNA complexes have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with the following accession codes: Dpo4-oxoA:dTTP (PDB Code: 6VGM) and DPO4-oxoA:dGTP (PDB Code: 6VG6).

Competing Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hemnani T and Parihar MS (1998) Reactive oxygen species and oxidative DNA damage. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 42, 440–452 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames BN (1989) Endogenous oxidative DNA damage, aging, and cancer. Free Radic Res Commun. 7, 121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talhaoui I, Couve S, Ishchenko AA, Kunz C, Schar P and Saparbaev M (2013) 7,8-Dihydro-8-oxoadenine, a highly mutagenic adduct, is repaired by Escherichia coli and human mismatch-specific uracil/thymine-DNA glycosylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 912–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grollman AP and Moriya M (1993) Mutagenesis by 8-oxoguanine: an enemy within. Trends Genet. 9, 246–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheng Z, Oka S, Tsuchimoto D, Abolhassani N, Nomaru H, Sakumi K, Yamada H and Nakabeppu Y (2012) 8-Oxoguanine causes neurodegeneration during MUTYH-mediated DNA base excision repair. J Clin Invest. 122, 4344–4361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Batra VK, Shock DD, Beard WA, McKenna CE and Wilson SH (2012) Binary complex crystal structure of DNA polymerase β reveals multiple conformations of the templating 8-oxoguanine lesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109, 113–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hsu GW, Ober M, Carell T and Beese LS (2004) Error-prone replication of oxidatively damaged DNA by a high-fidelity DNA polymerase. Nature. 431, 217–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brieba LG, Eichman BF, Kokoska RJ, Doublié S, Kunkel TA and Ellenberger T (2004) Structural basis for the dual coding potential of 8-oxoguanosine by a high-fidelity DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 23, 3452–3461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaruga P and Dizdaroglu M (1996) Repair of products of oxidative DNA base damage in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 1389–1394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuciarelli AF, Wegher BJ, Gajewski E, Dizdaroglu M and Blakely WF (1989) Quantitative measurement of radiation-induced base products in DNA using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Radiat Res. 119, 219–231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olinski R, Zastawny T, Budzbon J, Skokowski J, Zegarski W and Dizdaroglu M (1992) DNA base modifications in chromatin of human cancerous tissues. FEBS Lett. 309, 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jałoszyński P, Jaruga P, Oliński R, Biczysko W, Szyfter W, Nagy E, Möller L and Szyfter K (2003) Oxidative DNA base modifications and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon DNA adducts in squamous cell carcinoma of larynx. Free Radic Res. 37, 231–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard GA, Guy A, Brown T, Teoule R and Hunter WN (1992) Conformation of guanine-8-oxoadenine base pairs in the crystal structure of d(CGCGAATT(O8A)GCG). Biochemistry. 31, 8415–8420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wood ML, Esteve A, Morningstar ML, Kuziemko GM and Essigmann JM (1992) Genetic effects of oxidative DNA damage: comparative mutagenesis of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine and 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 6023–6032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamiya H, Miura H, Murata-Kamiya N, Ishikawa H, Sakaguchi T, Inoue H, Sasaki T, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Nishimura S and et al. (1995) 8-Hydroxyadenine (7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine) induces misincorporation in in vitro DNA synthesis and mutations in NIH 3T3 cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 2893–2899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan X, Grollman AP and Shibutani S (1999) Comparison of the mutagenic properties of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyadenosine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine DNA lesions in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 20, 2287–2292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Girard PM, D’Ham C, Cadet J and Boiteux S (1998) Opposite base-dependent excision of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine by the Ogg1 protein of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Carcinogenesis. 19, 1299–1305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen A, Calvayrac G, Karahalil B, Bohr VA and Stevnsner T (2003) Mammalian 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase 1 incises 8-oxoadenine opposite cytosine in nuclei and mitochondria, while a different glycosylase incises 8-oxoadenine opposite guanine in nuclei. J Biol Chem. 278, 19541–19548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grin IR, Dianov GL and Zharkov DO (2010) The role of mammalian NEIL1 protein in the repair of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroadenine in DNA. FEBS Lett. 584, 1553–1557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guschlbauer W, Duplaa AM, Guy A, Teoule R and Fazakerley GV (1991) Structure and in vitro replication of DNA templates containing 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 1753–1758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duarte V, Muller JG and Burrows CJ (1999) Insertion of dGMP and dAMP during in vitro DNA synthesis opposite an oxidized form of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 496–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koag MC, Jung H and Lee S (2020) Mutagenesis mechanism of the major oxidative adenine lesion 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 5119–5134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koag MC, Jung H and Lee S (2019) Mutagenic replication of the major oxidative adenine lesion 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoadenine by human DNA polymerases. J Am Chem Soc [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Wong JH, Brown JA, Suo Z, Blum P, Nohmi T and Ling H (2010) Structural insight into dynamic bypass of the major cisplatin-DNA adduct by Y-family polymerase Dpo4. EMBO J. 29, 2059–2069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ling H, Sayer JM, Plosky BS, Yagi H, Boudsocq F, Woodgate R, Jerina DM and Yang W (2004) Crystal structure of a benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide adduct in a ternary complex with a DNA polymerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 101, 2265–2269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eoff RL, Angel KC, Egli M and Guengerich FP (2007) Molecular basis of selectivity of nucleoside triphosphate incorporation opposite O6-benzylguanine by sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase Dpo4: steady-state and pre-steady-state kinetics and x-ray crystallography of correct and incorrect pairing. J Biol Chem. 282, 13573–13584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ling H, Boudsocq F, Woodgate R and Yang W (2004) Snapshots of replication through an abasic lesion; structural basis for base substitutions and frameshifts. Mol Cell. 13, 751–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zang H, Goodenough AK, Choi JY, Irimia A, Loukachevitch LV, Kozekov ID, Angel KC, Rizzo CJ, Egli M and Guengerich FP (2005) DNA adduct bypass polymerization by Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase Dpo4: analysis and crystal structures of multiple base pair substitution and frameshift products with the adduct 1,N2-ethenoguanine. J Biol Chem. 280, 29750–29764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zang H, Irimia A, Choi JY, Angel KC, Loukachevitch LV, Egli M and Guengerich FP (2006) Efficient and high fidelity incorporation of dCTP opposite 7,8-dihydro-8-oxodeoxyguanosine by Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase Dpo4. J Biol Chem. 281, 2358–2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vaisman A, Ling H, Woodgate R and Yang W (2005) Fidelity of Dpo4: effect of metal ions, nucleotide selection and pyrophosphorolysis. EMBO J. 24, 2957–2967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trincao J, Johnson RE, Wolfle WT, Escalante CR, Prakash S, Prakash L and Aggarwal AK (2004) Dpo4 is hindered in extending a G.T mismatch by a reverse wobble. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 11, 457–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Y, Wilson RC and Pata JD (2011) The Y-family DNA polymerase Dpo4 uses a template slippage mechanism to create single-base deletions. J Bacteriol. 193, 2630–2636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ling H, Boudsocq F, Plosky BS, Woodgate R and Yang W (2003) Replication of a cis-syn thymine dimer at atomic resolution. Nature. 424, 1083–1087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ling H, Boudsocq F, Woodgate R and Yang W (2001) Crystal structure of a Y-family DNA polymerase in action: a mechanism for error-prone and lesion-bypass replication. Cell. 107, 91–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vagin A and Teplyakov A (2010) Molecular replacement with MOLREP. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 66, 22–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emsley P and Cowtan K (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkóczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC and Zwart PH (2010) PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 66, 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS and Richardson DC (2007) MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC and Ferrin TE (2004) UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banerjee S, Brown KL, Egli M and Stone MP (2011) Bypass of aflatoxin B1 adducts by the Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase IV. J Am Chem Soc. 133, 12556–12568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Batra VK, Beard WA, Shock DD, Pedersen LC and Wilson SH (2008) Structures of DNA polymerase beta with active-site mismatches suggest a transient abasic site intermediate during misincorporation. Mol Cell. 30, 315–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao Y, Biertümpfel C, Gregory MT, Hua YJ, Hanaoka F and Yang W (2012) Structural basis of human DNA polymerase η-mediated chemoresistance to cisplatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109, 7269–7274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eoff RL, Irimia A, Angel KC, Egli M and Guengerich FP (2007) Hydrogen bonding of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxodeoxyguanosine with a charged residue in the little finger domain determines miscoding events in Sulfolobus solfataricus DNA polymerase Dpo4. J Biol Chem. 282, 19831–19843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rechkoblit O, Malinina L, Cheng Y, Kuryavyi V, Broyde S, Geacintov NE and Patel DJ (2006) Stepwise translocation of Dpo4 polymerase during error-free bypass of an oxoG lesion. PLoS Biol. 4, e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]