Abstract

Background:

Persisting high levels of relapse, morbidity and mortality in bipolar disorder (BD) in spite of first-line, evidence-based psychopharmacology has spurred development and research on adjunctive psychotherapies. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is an emerging psychotherapy that has shown benefit in related and comorbid conditions such as major depressive, anxiety, and substance disorders. Furthermore, neurocognitive studies of MBCT suggest that that may have effects on some of the theorized pathophysiological processes in BD.

Methods:

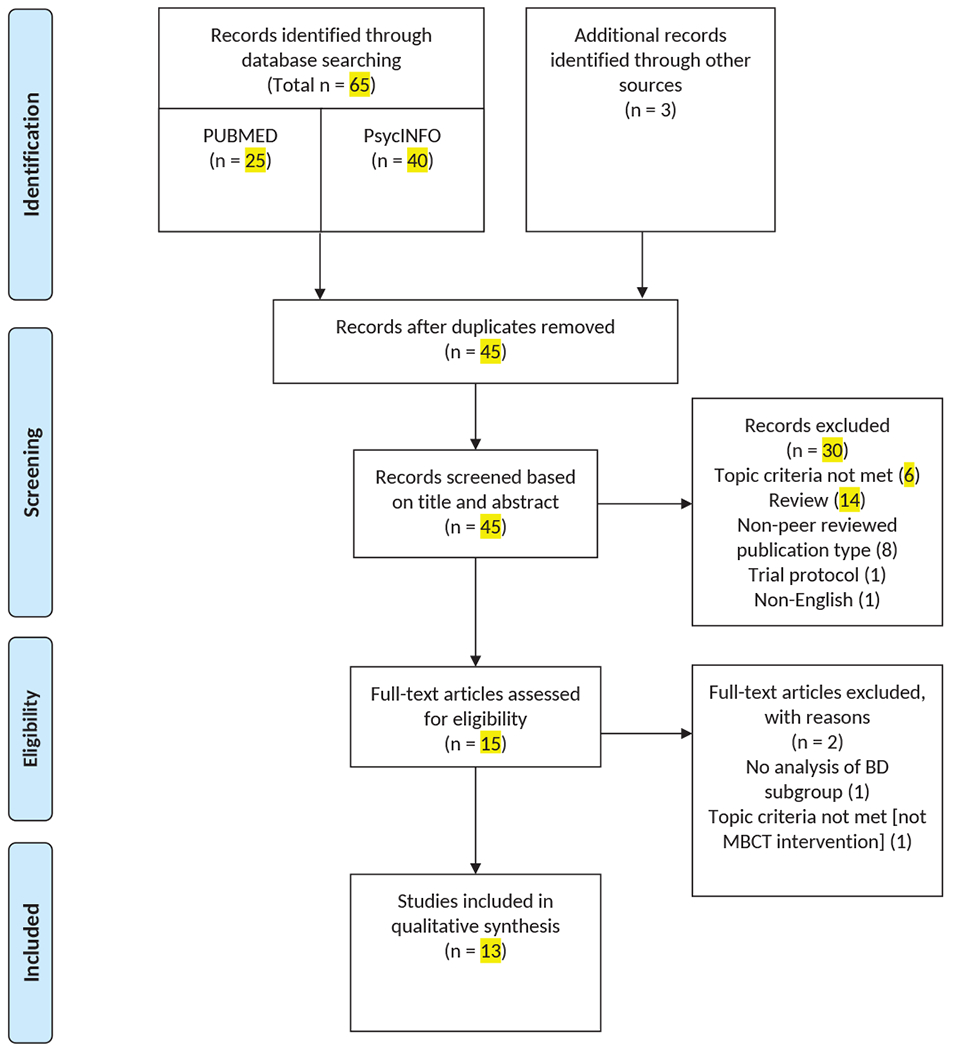

We conducted a systematic literature review using PsychINFO and PubMed databases to identify studies reporting clinical and/or neurocognitive findings for MBCT for BD.

Results:

This search revealed 13 articles. There was a wide range in methodological quality and most studies were underpowered or did not present power calculations. However, MBCT did not appear to precipitate mania, and there is preliminary evidence to support a positive effect on anxiety, residual depression, mood regulation, and broad attentional and frontal-executive control.

Limitations:

As meta-analysis is not yet possible due to study heterogeneity and quality, the current review is a narrative synthesis, and therefore net effects cannot be estimated.

Conclusions:

MBCT for BD holds promise, but more high-quality studies are needed in order to ascertain its clinical efficacy. Recommendations to address the limitations of the current research are made.

Keywords: bipolar disorder, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, psychotherapy, review

1. Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic and severe mental illness with high relapse, morbidity, and mortality rates despite existing evidence-based treatment options (Gitlin et al., 1995; Kilbourne et al., 2004; Novick et al., 2010). Comorbidity is common, especially with anxiety and substance use disorders, both of which have been associated with poorer course and quality of life, as well as greater likelihood of suicide attempts (Simon et al., 2004; Swann, 2010). The mainstay of treatment is pharmacotherapy, but augmenting psychotherapies have been developed in an attempt to improve the course of this disorder and address comorbid symptoms (Reinares et al., 2014). One of those emerging therapeutic interventions is mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT).

As a so-called ‘third-wave behavioral therapy’, MBCT—along with dialectical behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy, among others—aims to guide participants in the development of qualities such as mindfulness and acceptance for use in daily life (Hayes and Hofmann, 2017). Mindfulness can be defined as intentional, nonjudgmental, present-moment awareness. As in many of these therapies, cognitive-behavioral psychoeducational principles are discussed with participants, but with the focus on noticing the process of thinking rather than trying to change thoughts. MBCT differs from other third-wave interventions in its emphasis on formal mindfulness meditation practices, which include sitting and moving practices, such as walking meditation and yoga. These are typically taught in a weekly adult-educational group format over 8 weeks, that includes psychoeducation specific to the disorder, along with discussion of how and why mindfulness meditation can be useful. Sessions also teach formal, informal, and practical applied mindfulness. There is trouble-shooting and group discussion within sessions, and an expectation of daily home meditation practice between sessions. This repetitive attentional training builds the capacity to increasingly become aware of cognitions, affects, and behaviors from an attitude of compassion and acceptance, which is associated with less behavioral and affective reactivity and a greater sense of well-being (Creswell, 2017).

MBCT has been shown to decrease the rate of relapse of major depressive disorder (MDD), with efficacy comparable to antidepressant medication (Kuyken et al., 2015). Positive effects have also been shown for anxiety symptoms (Hoge et al., 2013). While MBCT has not been studied for the treatment of substance use disorders, a related modality, mindfulness-based relapse prevention, has demonstrated efficacy for these conditions (Bowen et al., 2014). Thus, from a symptomatic perspective, the application of MBCT to bipolar disorder seems promising. In addition, there are mechanistic reasons to suspect that MBCT might be helpful.

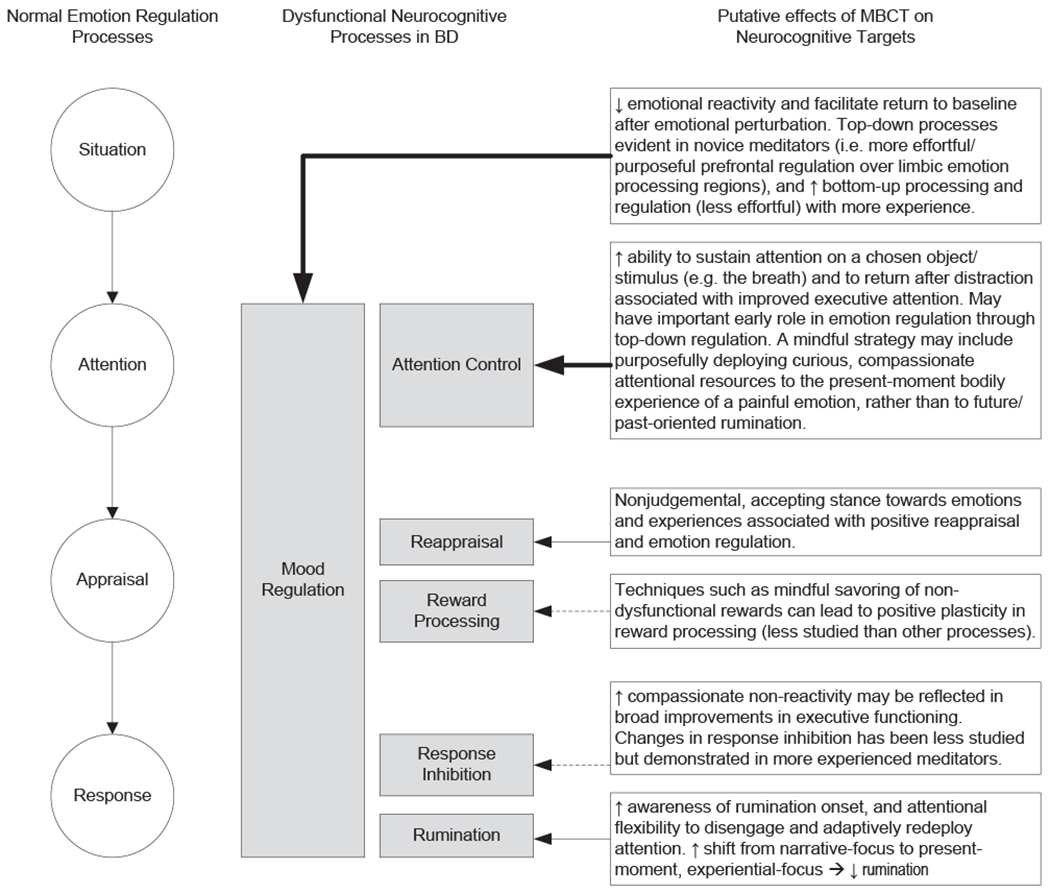

A recent review and synthesis of the most influential neurocognitive models of mood disorders found that there was convergent evidence for 6 key processes of psychopathology: dysfunctional reappraisal, rumination, attention, mood regulation, reward processing/motivation, and response inhibition/impulsivity (Malhi et al., 2015). More recent systematic reviews and meta-analysis further implicated several of these neurocognitive processes in BD, namely rumination (Silveira Jr. and Kauer-Sant’Anna, 2015) and executive functioning deficits, including attention and inhibition (Cardenas et al., 2016; Dickinson et al., 2017). Recent expert reviews have also highlighted the centrality of abnormal reward processing (Ashok et al., 2017) and mood dysregulation (Harrison et al., 2018) in BD. Although less studied, there is evidence that partially or fully remitted patients with BD have even greater difficulty regulating emotions using cognitive reappraisal than those with unipolar depression (Kjærstad et al., 2016).

The cultivation of mindfulness strengthens the ability to decenter from thoughts, and to perceive them as transient mental stimuli, rather than facts. As such, mindfulness and MBCT have been shown to facilitate adaptive cognitive reappraisal (Garland et al., 2009, 2011; Troy et al., 2013). Patients with BD have been shown to have lower levels of trait mindfulness (Gilbert and Gruber, 2014; Perich et al., 2011) and high levels of rumination (Kim et al., 2012; Silveira Jr. and Kauer-Sant’Anna, 2015) than healthy controls. Furthermore, an experimental induction in participants with BD demonstrated that the mindfulness condition was associated with increased positive emotion and parasympathetic functioning, while the rumination condition was associated with an exacerbation of emotional reactivity and autonomic disturbance (Gilbert and Gruber, 2014). MBCT for other conditions has been shown to decrease maladaptive rumination, and this was associated with clinical improvement (Gu et al., 2015; Heeren and Philippot, 2011; van Vugt et al., 2012). Thus, it seems that the heightened rumination in BD found across mood states (Silveira Jr. and Kauer-Sant’Anna, 2015) may be an important therapeutic target for MBCT.

Extensive research with clinical and nonclinical populations has demonstrated the positive effects of mindfulness training on attentional control, emotion regulation, and related brain structures (for review see Tang et al., 2015). Less studied have been the potential effects of mindfulness training on response inhibition and reward processing. However, two studies have demonstrated improved response inhibition in healthy controls after mindfulness training (Allen et al., 2012; Sahdra et al., 2009). Preliminary findings also suggest that mindfulness can remediate reward processing in chronic pain participants at risk for opioid misuse, another group with characteristic deficiencies in this domain (Garland et al., 2015).

Lastly, the issue of practice and ‘dose’ is one that is being examined within the broader mindfulness literature (Creswell, 2017). Arguably, it is particularly relevant in a disorder such as BD, which features prominent neurocognitive deficits, particularly involving the attentional system, even during periods of euthymia or remission (Cardenas et al., 2016; Dickinson et al., 2017). Therefore, examining how successful studies modify the protocol to engage and retain the BD population will be important.

Thus, evidence from clinical trials for other psychiatric conditions and from neurocognitive findings suggest that mindfulness training through MBCT may prove a useful psychotherapeutic adjunct to psychopharmacology in BD. In the current paper, we aim to review and qualitatively synthesize the existing data regarding the effects of MBCT on the clinical features and neurocognitive processes associated with BD, as well as data relevant to the issue of practice ‘dose’. As there is increasing recognition that psychotherapy research must look for potential harms as well as benefits of interventions (Berk and Parker, 2009; Linden, 2013; Van Dam et al., 2018), we examine the current literature for any potential evidence of destabilization or harm. Lastly, we aim to identify the weaknesses in the current literature to inform clinical decision-making and future research efforts.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility

Studies were eligible if they met 2 topic criteria: 1) included participants with DSM-IV or DSM-5 bipolar disorder (BD); and 2) participants were treated with mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). Other non-MBCT modalities featuring mindfulness such as dialectical behavioral therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based relapse prevention, were excluded. Only English language articles were reviewed. Studies with heterogeneous diagnostic populations that did not provide separate analyses of the BD subgroup necessary to extract information concerning the effect of this intervention in this population were excluded. Quantitative and qualitative studies were included. There were no date restrictions. We performed the original search on October 26, 2016, and a secondary search on February 19, 2018.

2.2. Search Strategy

We searched for potential articles in Pubmed and PsycINFO databases. The following key terms were searched within these databases: “bipolar disorder” and “mindfulness-based cognitive therapy”.

2.3. Study Selection

Initially, we assessed all broadly relevant papers for eligibility based on titles and abstracts. Reviews, books, editorials, letters, dissertations, protocols of upcoming studies, non-peer reviewed publications, and non-English articles were excluded. Then a full-text review was conducted. Eligible studies were divided into those examining clinical effects (open-label trials and randomized control trials [RCTs]), those examining possible mechanisms (e.g. neuroimaging studies), or those examining both.

2.3. Quality assessment

We independently assessed the quality of selected studies using the checklist developed by Downs and Black for randomized and non-randomized studies (Downs and Black, 1998). Potential scores ranged from 0 (lowest possible quality) to 28 (highest possible quality. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Table 1 shows the quality assessment total score assigned to each study.

Table 1.

Description of the 13 included studies

| Study + Quality Score (QS)* | Participant n (BD MBCT/BD wait list control [WLC]/Healthy control [HC]) + Clinical status/characteristics of BD participants | MBCT Group Intervention | Completion rate of MBCT | Follow-up | Summary of Findings (1. = Primary focus; 2. = Secondary focus; Clinical or Neurocognitive Process) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | |||||

|

Ives-Deliperi et al, 2013 QS: 14 |

16/7/10 BD I or II Mild or subthreshold mood symptoms BL YMRS = 3 BL HADS = 5.9 [“normal” range] |

BD only group; 8-week group (paucity of description) | 16/16 (100%) completed | Immediately post-MBCT |

1. Process – fMRI BOLD signal in medial prefrontal cortex during a mindfulness task significantly reduced in BD compared to HC; improved signal following MBCT (along with posterior cingulate). Mindfulness (FFMQ) also improved and correlated with fMRI findings. BD group had significant neuropsychological impairments relative to HC in 3/8 domains. 2/3 of these significantly improved after MBCT (Digit span backward, Rey Complex Figure-Recall; but not Stroop inhibition). 2. Clinical – only baseline clinical measures that were significantly higher in BD group relative to HC were anxiety (BAI) and symptoms of stress (SOSI; note: no significant difference in depressive scores [HADS]). Post-intervention, the BD MBCT group showed significant improvement in anxiety, and emotion regulation (DERS) compared to waitlist control BD group. |

| Perich et al, 2013a QS: 23 |

48/47/- (randomized to condition; intention to treat analysis [ITT]) BD I or II BL YMRS = 4.98 BL MADRS = 11.71 [<10 = “remission”] |

BD only group; 8-week group with BD modifications | 38/48 started MBCT after randomization 34/38 (89.5%) completed at least 4 sessions; mean number of sessions = 7 (SD=0.94; range 4-8) | Immediately post-MBCT, 3-, 6-, 9-, 12-months |

1. Clinical – ITT analysis: recurrence rates to any mood episode were not significantly different between BD MBCT and WLC. Nor were mood symptom scores (MADRS; YMRS). Secondary analysis showed another measure of depressive symptoms (DASS depression subscale) failed to show significant change, but 1 of 3 measures of anxiety showed a significant time x treatment interaction (STAI-state anxiety subscale, but only a trend for the trait subscale, and not for the DASS anxiety subscale). 2. Process – Time x treatment interactions only significant for 1 of 3 dysfunctional attitudes subscales (DAS-24; achievement, not dependency or goal attainment). No significant time x treatment interactions for rumination (RSQ) or mindfulness (MAAS). |

|

Williams et al, 2008 QS: 16 |

9/8/- BD (did not specify I or II) BL YMRS = NR (but no manic episodes for at least 6 months) NIMH criteria for recovery BL BDI = 15.8 [“mild” range] History of “serious suicidal ideation or behavior” |

Mixed sample in groups (MDD & BD); 8-week group (no BD modification) | 7/9 (77.8%) completed | Immediately post-MBCT |

1. Clinical – No main effects on anxiety (BAI) or depression (BDI); however, anxiety was significantly lower in the BD MBCT group compared to the WLC – with the anxiety of the WLC increasing over time, and the BD MBCT group not increasing. Depression scores. This effect was not seen in the MDD participants. Depression scores were low at baseline and the average scores were lower at time 2 but this was not statistically significant. No process data |

| Open-label trials | |||||

|

Deckersbach et al, 2012 QS: 14 |

12/-/- BD I or II BL YMRS = 5.4 BL HAMD = 11.8 [“mild” range] Residual depression symptoms but subthreshold for a MDE |

BD only group; 12-week; significant BD adjustments to MBCT protocol (more movement practices, loving-kindness practices, problem-solving, more sessions) 120 minutes/session | 10/12 met criteria for the ITT analysis (2 dropped out after screening) 9/10 (90%) completed; average of 8.5 sessions | Immediately post-MBCT and 3 months |

1. Clinical – ITT analysis: significant decrease in residual depressive symptoms (HAMD) – which were all mild to moderate in severity at baseline; maintained at follow-up; large effect size. No change in manic symptoms (YMRS) – which were low at baseline. Significant decreases in worry (PSWQ); maintained at follow-up; large effect size. Psychosocial functioning improved (LIFE-RIFT) significantly with a large effect pre-post, which was maintained at follow-up. 2. Process – Significant improvement in 3/5 mindfulness subscales (FFMQ; observing, nonjudging, nonreacting; not for describing, or acting with awareness). Significant improvement in rumination (RSQ) and emotion regulation (ERS); both maintained at follow-up; both large effect sizes. Significant improvement in self-report attentional difficulties – maintained at follow-up, moderate effect size; but no changes in symptoms of hyperactivity (ASRS). Psychological Well-being (PWBS) showed significant changes in 4/6 subscales (environmental mastery, positive relations, purpose in life, self-acceptance; but not personal growth, or autonomy). Positive Affect (CPAS) improved significantly. |

|

Howells et al, 2012 QS: 10 |

12/-/9 BD I BL YMRS = 3.41 BL HADS = 5.08 (not significantly different than HC) [“normal” range] “Euthymic state” |

BD only group; 8-week; included psycho-education with focus on the early warning signs of mania & depression | 12/12 (100%) completed | Immediately post-MBCT |

1. Process – On baseline resting eyes-closed EEG, compared to healthy controls (HC), BD group showed decreased theta and increased beta band power over the frontal and cingulate cortices, with no differences in parietal cortex during resting eyes closed. Authors described this pattern as suggestive of decreased attentional readiness. On baseline attentional-task ERP, BD group showed significant differences in P300-like waveform over the frontal cortex in response to the target stimulus, compared to HC. Authors described this pattern as suggestive of non-relevant information processing. Post-MBCT, the resting EEG showed improvement of ¼ of the above differences (significant decrease of beta band power over the frontal cortex). Post-MBCT, the P300-like waveform difference seen at BL was attenuated. Authors interpreted this as improved attentional readiness and decreased non-relevant information processing, respectively, post-MBCT. 2. Clinical – At baseline, BD group had significantly higher mean YMRS than HC, but there was no difference between groups on depression or anxiety scores (HADS). There was no further reduction post-MBCT. |

|

Howells et al, 2014 QS: 12 |

12/-/9 BD I See Howells et al, 2012 |

BD only group; 8-week; included psycho-education with focus on the early warning signs of mania & depression | 12/12 (100%) completed | Immediately post-MBCT |

1. Process – Emotional processing found to be impaired in BD participants relative to HC, as demonstrated by increased ERP N170 amplitude during an affective task (matching, labeling), and increased high-frequency heart-rate variability (HRV) peaks during the affective matching task (but not labeling). Post-MBCT, these findings were attenuated, suggesting improved emotional processing. 2. Clinical – Repetition of Howells et al, 2012. Added that YMRS scores did not change. Note: Howells et al, 2012 and 2014 are based on the same clinical sample/trial, but present different mechanism data. |

|

Miklowitz et al, 2009 QS: 13 |

22/-/- BD I or II BL YMRS = 2.14 BL HAMD = 5.45 [“remission” range] |

BD only group; minor BD adjustments to MBCT protocol; 8-week | 19/22 started MBCT after being accepted 16/19 (84.2%) completed (or 16/22 assigned – 72.7%) | Immediately post-MBCT |

1. Clinical – Pre- to post-MBCT statistical tests of difference were not presented. Authors presented Cohen’s d as estimated effects from pre to post; however, all of the 95% confidence intervals crossed 0. All of the mean scores of mood (YMRS, HAMD, BDI), anxiety (BAI), and suicide (BSIS) symptoms were all decreased at post-MBCT, but these can only be considered trends, given the absence of statistical verification. No process data |

|

Miklowitz et al, 2015 QS: 15 |

12/-/- BD I, II, NOS, cyclothymia BL YMRS = 4.1 BL HAMD = 3.14 [“remission” range] Peripartum women |

BD with MDD group; 8-week; 2-hrs/wk; no major modifications for BD noted | 7/12 (58.3%) completed | Immediately post-MBCT, 1 month, and 6 months |

1. Clinical – BD data taken from the broader study that focused on MBCT for peripartum women with mood disorders (MDD or bipolar spectrum disorders). Women with BD did less well than those with MDD: more drop-outs (41.7 vs 7.4%; higher YMRS was a predictor), and depression scores (HAMD) worsened in BD over the course of MBCT (improved in MDD). No change in anxiety (STAI-C) and YMRS. Only 33.3% of BD group were on medication. During follow-up 21.9% met criteria for a major depressive episode, but diagnostic status (MDD vs BD) was not predictive. 4 patients with BD had hypomanic episodes during follow-up, but no manic or mixed episode. There was no waitlist control to determine whether this was indicative of the disorder’s natural history versus some improvement or detriment associated with MBCT. 2. Process – Baseline mindfulness (FFMQ) was higher among the BD group, as compared to the MDD group. Mindfulness increased overall (MDD and BD), but less so in BD. |

|

Stange et al, 2011 QS: 12 |

12/-/- BD I or II [see Deckersbach et al, 2012] Residual depression symptoms but subthreshold for a MDE |

BD only group; 12-week; significant BD adjustments to MBCT protocol (more movement practices, loving-kindness practices, problem-solving, more sessions) 120 minutes/session | 10/12 began MBCT 9/10 completed |

Immediately post-MBCT and 3 months |

1. Mechanism – At baseline, self-report scores on 2 executive functioning scales (FrSBe, BRIEF) showed significant impairment in multiple domains compared to normative scores (no comparison group). Post-MBCT, the composite scores for either scale did not change significantly. On the BRIEF, 2/9 subscales improved significantly (initiate, working memory; but not inhibit, shift, emotional control, self-monitor, plan/organize, task monitor, organization of materials), with large effect sizes, maintained at follow-up. On the FrSBe, 2/3 subscales significantly improved (apathy, executive functioning; but not disinhibition), with large effect sizes, maintained at follow-up. There was no correction for multiple comparisons. Given this, it is difficult to interpret the correlation of changes in symptom measures (HAMD, YMRS) and mindfulness subscales (FFMQ) with executive functioning subscales (7 scales/subscales correlated with 16 scales/subscales, respectively). No clinical data Note: This paper is a secondary analysis of the Deckersbach et al (2012) study. |

|

Weber et al, 2010 QS: 11 |

23/-/- BD I or II or NOS BL YMRS = 2 BL MADRS = 8 BL BDI = 10 [medians; “remission” & “minimal” ranges, respectively] |

BD only group; minor BD adjustments to MBCT protocol; 8-week; 2 hrs/wk | 21/23 completed the initial assessment and attended the first session; 15/23 (71.4%) attended at least 4 sessions-analyses were conducted on this group (n=15); only had post-MBCT data on 11; 3-months: n=9 | Within 1 month post-MBCT and 3 months |

1. Clinical – No significant improvement in depressive (BDI, MADRS) or manic (YMRS) symptoms post-MBCT. Anxiety not measured. It appears that for depressive scores, half of the group improved, and half of the group worsened, but no clinical sub-analysis was conducted to understand this effect (likely untenable due to low n). 2. Process – No significant overall improvement in mindfulness (KIMS) post-MBCT. However, there was a significant correlation between improvement in mindfulness scores and improvement in depressive scores. |

| Cohort | |||||

| Perich et al, 2013b QS: 16 |

23/-/- BD I or II All on medication |

BD only group; 8-week group with BD modifications | N/A – this study is an analysis of completers who also provided homework information (23/34 [67.6%] of the Perich et al, 2013a participants; 22 at 12-month follow-up) |

12-month follow-up |

1. Process – Examined effect of homework or ‘dosage’ on outcome variables. During the 8-week intervention, participants practiced, on average, at least once a day for 26.4 days (range 5-44; out of 56 days; i.e. 47% of days). Number of prior bipolar episodes was the only significant baseline predictor of practice (negative correlation; thought suppression, trait mindfulness, prior hospitalizations, and symptom measures were not correlated). Practice was not significantly correlated with any of the post-MBCT symptom scores (YMRS, MADRS, DASS, STAI). However, at 12-month follow-up, practice during the 8-week program was significantly inversely correlated with depression (MADRS) scores (but none of the other scales/symptoms). As a secondary analysis, the sample was dichotomized into those who practiced meditation at least once a day for 3 or more days/week and those who practiced 2 days or less/week. The more frequent group had significantly lower STAI trait anxiety scores, and lower MADRS scores at 12-month follow-up. In a separate analysis, there was no difference in symptom or MAAS scores between those who continued to meditate at 12-month follow-up and those who did not (13 vs 9, respectively). No clinical data Note: This paper is a secondary analysis of the Perich et al (2013a) study. |

| Cross-sectional Follow-up Survey | |||||

|

Weber et al, 2017 QS: 10 |

71/-/- BD I or II Naturalistic clinical sample; only exclusion criteria was current abuse or dependence to alcohol or other substances 70/71 were on medication |

Did not specify if BD only or not; 8-week group; did not specify any BD modifications | N/A – this study only includes those who have attended at least 4/8 MBCT sessions | Majority surveyed (70.4%) were at least 2 years after termination of MBCT |

1. Process – A cross-sectional retrospective survey (no pre-MBCT measure to compare) of participants found formal daily mindfulness practice was infrequent, with the most commonly practiced meditation (3-minute breathing space) only being conducted by 11.3% of their sample on a daily basis. But 54.9% reported practicing formally at least once a week, mostly for 30 minutes or less (88.6%) on average. Those who practiced the 3-minute breathing space at least once a week rated MBCT as more beneficial in preventing depression than those who practiced less than once a week. Perceived benefit on other domains (hypomania/mania prevention; long-lasting effects; persistent change in way of life or philosophy) did not differ based on amount of formal practice. Informal practices (mindful daily activities) were endorsed as occurring daily by 14.1%, and at least once a week by 57.7%, and the latter perceived MBCT as more beneficial in inducing persistent change in way of life or philosophy (than those who practiced less). But perceived benefit on other domains did not differ based on the amount of informal practices. Participants most consistently perceived that MCBT improved facets of self-efficacy in their survey (e.g. 92% felt it improved their “being aware that I can help improve my own health”). Facets related to mindfulness and self-compassion were also perceived to have improved. “Feeling full of hope” had the fewest participants who perceived a positive change, but it was still the majority (52%). The authors did not report on any perceived negative changes. 1. Clinical – Perceived benefit on a 10-point likert scale (1=not at all to 10=enormously) demonstrated a median rating of 5 for prevention of depression of 5, and 6 for prevention of hypomania/mania. |

| Qualitative | |||||

|

Chadwick et al, 2011 QS: 7 |

12/-/- BD Had attended at least 4/8 MBCT sessions plus a 6-week booster session |

BD only group; 8-week group with some BD modifications (including shorter practices); 90-minute sessions; plus 6-week booster session | N/A – this study only includes those who have attended at least 4/8 MBCT sessions | Within 2-4 weeks of 6-week booster session (i.e. 18-20 weeks after groups began) |

1. Process – A semi-structured interview was developed following literature review and expert discussion. Three main open questions: “How would you describe mindfulness? What is it like practicing mindfulness? In your experience, how does mindfulness practice relate to living with BD?” Interviews were coded and thematic analysis revealed 7 themes: focusing on what is present; clearer awareness of mood state and mood change; acceptance; adapting mindfulness practice to different mood states; reducing and stabilizing negative affect; relating differently to negative thoughts; reducing impact of mood state. No clinical data |

Scales: ASRS = Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale 1.1; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BSIS = Beck Suicide Ideation Scale, CPAS = Clinical Positive Affect Scale, DAS-24 = Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale, DASS = Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale, ERS = Emotion Reactivity Scale, FFMQ = Five-Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire, HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, HAMD = Hamilton Depression Scale, KIMS = Kentucky Inventory of Mindfulness Skills, LIFE-RIFT = Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation – Range of Impaired Functioning Tool, MAAS = Mindful Attention Awareness Scale, MADRS = Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire, PWBS = Psychological Well-Being Scale, RSQ = Response Style Questionnaire, SOSI = Symptoms of Stress Inventory, STAI-C = State/Trait Anxiety Inventory-Current Status Scale, STAI = State/Trait Anxiety Inventory, YMRS = Young Mania Rating Scale

Other: BD = Bipolar disorder, EEG = Electroencephalography, ERP = Event-Related Potentials (of EEG), fMRI = Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, HC = Healthy Control, ITT = Intention To Treat, MBCT = Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy, WLC = Wait list control

Depression Cut offs: BDI = 0-13 = minimal; 14-19 = mild, HAMD = <7 = remission; 7-17 = mild depression, HADS = 0-7 = “normal”, MADRS = <10 = remission (Bjelland et al., 2002; Cusin et al., 2010; Zimmerman et al., 2004)

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

The results of the search strategy are summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1). The majority of excluded records based on the abstract screen were reviews. Two articles were excluded in the full-text review. One was a ‘real-world’ effectiveness study of MBCT that included BD participants (among a larger cohort with depression), but that did not provide an analysis of this subgroup (Meadows et al, 2014). The other article studied another heterogeneous psychiatric sample, but the intervention was not specifically MBCT (Bos et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Diagram

Of the 13 studies found, 10 examined clinical symptoms (e.g. depression, anxiety, etc) and 11 examined neurocognitive processes associated with BD. Within the clinical studies, 2 examined exclusively clinical effects, the remainder examined both clinical and neurocognitive processes (see Table 1). Among the clinical studies, there were 3 randomized control trials (RCTs), and 6 open-label trials. However, it should be noted that 2 of these open-label papers (Howells et al., 2014, 2012) concerned the same sample/trial, but focused on different neurocognitive processes. Therefore, in the clinical summaries, this will be considered one sample/study, for a total of 7 unique clinical samples/studies. Two other studies (Deckersbach et al., 2012; Stange et al., 2011) presented different data sets on the same sample/trial, but did not re-present the same clinical data.

Among the neurocognitive processes studies, there were 5 clinical trials that assessed levels of mindfulness by self-report measures, 3 studies measuring neural biomarkers (functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI], electroencephalography [EEG], event-related potential [ERP]), 1 study measuring an autonomic biomarker (heart-rate variability [HRV]), 1 study assessing cognitive functioning by self-report measure, 1 study assessing cognitive functioning by neuropsychological testing, and 1 qualitative study using semi-structured interviews and thematic analysis.

One study examined the correlation of practice effects with clinical outcomes, one retrospective survey asked for participants’ subjective perception of benefit and practice, and all of the clinical studies (7) reported on class completion rates (a proxy for practice/dose).

3.2. Summary of Clinical/Symptomatic Findings

The clinical study characteristics and findings are detailed in Table 1. The following summarizes the findings for the various clinical symptoms studied.

3.2.1. Mania

As all of the studies involved BD patients in remission from all manic/hypomanic/mixed episodes, there was a floor effect on mania scores (e.g. Young Mania Rating Scale, YMRS). The studies could not be expected to show an improvement on already low to non-existent manic symptoms. However, there was no significant increase in manic symptoms over the course of the MBCT intervention in any of the studies, suggesting that it was not destabilizing.

There was only one study that assessed for the possible effect of MBCT on decreasing risk of relapse into manic/hypomanic episodes following the intervention (Perich et al., 2013a). There was no significant difference with the treatment-as-usual control group on time to relapse or severity of manic/hypomanic symptoms at 12-month follow-up. While this was one of the largest studies on MBCT for BD, by their own reported power calculations, the study was not adequately powered to find a potential difference. No other study was designed or powered to detect relapse over a sufficient time period. In a cross-sectional survey, conducted an average of 2 years after their MBCT group, participants reported a perceived benefit in preventing mania/hypomania (Weber et al., 2017). Despite lack of evidence of an effect on mania, there is preliminary evidence that MBCT may have a positive effect on mood dysregulation as described below.

3.2.2. Depression

All 8 clinical trials measured depressive symptoms. Only 2 trials found a significant positive effect on depressive symptoms – 1 RCT and 1 open-label trial (Deckersbach et al., 2012; Williams et al., 2008). However, these were 2 of only 3 trials that had clinically significant levels of residual depressive symptoms at baseline (See Table 1; (Deckersbach et al., 2012; Perich et al., 2013a; Williams et al., 2008)). The mean baseline scores of the remainder were in the “remission” range, thus representing a considerable floor effect. For example, Howells et al (2012) had a BD group in which the mean depressive score was not statistically different from the healthy controls at baseline. Deckersbach et al (2012), was the only trial that specifically had “residual depressive symptoms” (at least 3 days every week for the preceding month, but subthreshold for a major depressive episode) as an inclusion criteria (other studies had a current major depressive episode as exclusion criteria) and the mean baseline HAMD scores were 11.8, which is in the “mild depression” range (7-17).

The negative Perich et al (2013) study had mean baseline MADRS scores that were just above the remission level. It was an RCT designed to detect potential effects on relapse prevention, but unfortunately their recruitment did not meet their own power calculations and was thus underpowered. They did not find any significant decrease in depressive symptoms or time to relapse, as compared to waitlist controls.

One open-label study reported positive effects from pre- to post-treatment (Cohen’s d = 0.37 and 0.49 for Hamilton Depression Rating Scale & Beck Depression Inventory, respectively), but the 95% confidence intervals crossed 0, suggesting that we cannot be confident of an effect (Miklowitz et al., 2009). A study of a peripartum women in mixed diagnoses groups (MDD and BD) found a significant diagnosis-by-time interaction that showed that depression scores improved in the MDD participants, but worsened in the BD participants over time (Miklowitz et al., 2015). However, it should be noted that without a BD control group the worsening cannot be definitively attributed to the treatment, and could instead reflect the natural history of the disorder, particularly given that the majority of the BD participants were unmedicated. This is in contrast to the rest of the studies, in which almost all participants were medicated. In the same retrospective cross-sectional survey noted above, in which 70/71 former participants were on medication, a moderate benefit for the prevention of depression relapse was perceived (Weber et al., 2017).

In sum, the question of the effect of MBCT on depressive symptoms has not been adequately tested. When participants have mild residual symptoms at baseline there are some positive findings from 1 open-label trial and 1 RCT, and a negative finding from 1 underpowered RCT. More investigation is needed with patients with residual depressive symptoms.

3.2.3. Anxiety

Of the 8 clinical trials, 7 reported on anxiety measures. The 3 RCTs all found some evidence of beneficial effects of MBCT over waitlist control on anxiety measures (Ives-Deliperi et al., 2013; Perich et al., 2013a; Williams et al., 2008). However, the Williams et al (2008) trial did not find improvements in anxiety during the trial. Rather, the control group worsened in anxiety measures, but the treatment group did not. This suggested that MBCT may have protected against worsening of anxiety. Of note, in the Perich et al (2013) trial, only one of the three anxiety measures reported found a significant difference (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-State, but not State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Trait or Depression Anxiety Stress Scales).

In the 4 open-label trials that measured anxiety, only Deckersbach et al (2012) found a significant improvement in anxiety (large effect) after their 12-week group tailored for BD patients, which was maintained at 3-month follow-up. The negative trials were all 8-week MBCT groups, with less specificity/modifications for BD, and had several important limitations. One of the studies reported improved anxiety scores, but the statistics reported were Cohen’s ds (small effect, in the case of anxiety) with confidence intervals that crossed 0 (Miklowitz et al., 2009). In MIklowitz et al (2015), the majority of the BD participants were unmedicated, as discussed above. The other negative trial (Howells et al., 2012, 2014) had a floor effect, as the anxiety levels of the BD group at baseline were not significantly different than the healthy control group.

In sum, the positive effects on anxiety were more commonly found in the higher quality, controlled studies (3/3 versus 1/4 open-label trials), and after a higher MBCT ‘dose’ of 12 weeks. This suggests that perhaps the MBCT groups that were more tailored to BD had a more potent effect on symptoms related to this specific psychopathology, or that the more homogeneous group environment was somehow more beneficial.

3.2.4. Suicide

Only one study reported that they assessed the effects on suicidality using self-report; it did not find any significant change during the trial (Miklowitz et al., 2009). The Williams et al (2008) study was an analysis of a BD subsample within a MBCT for suicidality trial, but they did not report any of the suicidality data.

3.3. Summary of Findings Related to Neurocognitive Processes Associated with Bipolar Disorder

As described in the introduction, a review and synthesis of the neurocognitive models of mood disorders implicated dysfunction in 6 key processes (Malhi et al., 2015). We summarize the reported effects of MBCT for BD on these factors below. Qualitative and quantitative studies are included. Figure 2 provides a schematic illustration of these neurocognitive processes in BD and how they may be targeted by MBCT, including the relative strength of the current evidence for each domain.

Figure 2.

Putative neurocognitive processes in BD as potential targets for MBCT. The schematic illustrates: 1) normal emotion regulation processes (circles on the left), 2) their corresponding dysfunctional processes in BD (shaded boxes), and 3) how MBCT putatively targets these processes based on mindfulness theory and findings in other disorders (boxes on the left). Arrows connecting the boxes (#2 and 3) represent the available evidence of MBCT for BD in the given domain: bold arrows = multiple studies with positive findings; thin arrows = more than 1 study, but with some studies that failed to find an effect; dotted arrows denote that the domain is not yet sufficiently assessed, yet is a theoretical target of MBCT for BD. See Malhi et al (2015) review for details regarding research supporting #1 and 2. See Tang et al (2015) and Holzel et al (2011) for reviews proposing neurocognitive mechanisms of mindfulness.

3.3.1. Reappraisal

One prominent theme that emerged from a qualitative study of MBCT participants with BD was that they responded differently to negative thoughts as a consequence of mindfulness practice (Chadwick et al., 2011). Decentering and an awareness that thoughts are not facts helped participants become less distressed by their thoughts. Approaching negative thoughts and affects with an attitude of mindfulness, instead of personalizing and ruminating on the mental content, is the primary reappraisal taught in MBCT, and participants seemed to find it helpful. They reported being able to detect mood changes more quickly and feeling less overwhelmed by these changes. Additionally, they also reported improved acceptance and self-compassion.

No quantitative study assessed reappraisal directly. However, many studies examined the mindfulness construct. Although mindfulness is a broader construct than reappraisal, and has been conceptualized as ‘nonappraisal’ (Hölzel et al., 2011), strengthening mindfulness has been shown to facilitate adaptive cognitive reappraisal (Garland et al., 2009, 2011; Troy et al., 2013). As such, we summarize the mindfulness mechanism data from MBCT for BD in this section.

Of the 7 clinical trials, 5 reported using self-report mindfulness measures. Three of the 5 found evidence of improvements in mindfulness after the MBCT intervention. All 3 of the positive trials were using the FFMQ. The two negative trials used the KIMS and MAAS. Of the two RCTs that measured mindfulness, 1 found a positive effect (Ives-Deliperi et al., 2013), and one did not find an effect (Perich et al., 2013a).

Only 2 trials reported on the subscales of mindfulness measures (Deckersbach et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2010). Weber et al (2010) did not find any significant changes of the KIMS subscales over their trial. Deckersbach et al (2012) reported that the FFMQ subscales “observing”, “non-judging” and “nonreacting” improved, while “describing” and “acting with awareness” did not. The improvement they found in the “non-judging” facet was positively correlated with improvements in self-reported executive functioning, disinhibition, and behavioral regulation (Stange et al., 2011). Improvement in “acting with awareness” was positively correlated with improvement in self-report measures of executive function (Stange et al, 2011). However, these results are difficult to interpret in the absence of statistical correction for multiple comparisons.

Ives-Deliperi et al (2013) also found that improvement in mindfulness, as measured by the FFMQ, was associated with a ‘normalization’ of medial prefrontal cortex activation. This is notable as functional abnormalities in this region are associated with both mood lability and self-focused maladaptive rumination.

The 2 studies that examined the correlation between improvement in mindfulness and depressive scores found a positive relationship (Weber et al, 2010; Miklowitz et al, 2015). The Weber et al (2010) trial specifically found an association between improvements in “observing” and in depression. No mediation analysis was reported in any of the studies.

In sum, reappraisal by way of mindfulness has some early support as a process of BD that is potentially targetable by MBCT. Improvements in mindfulness may be associated with other potential processes, theory-consistent neural changes, and improvements in depression. The self-report measure of mindfulness most sensitive to change in these studies appears to be the FFMQ.

3.3.2. Rumination

Qualitative analysis of MBCT participants with BD found that mindfulness practice helped reduce rumination by way of decentering (as above; Chadwick et al, 2011). Of the 2 trials reporting self-report measures of rumination, one open-label trial found an effect (Deckersbach et al, 2012), and one RCT did not (Perich et al, 2013a). These qualitative and self-report findings are also supported by the normalization of medial prefrontal cortex found in the Ives-Deliperi et al (2013) study, as this region is associated with rumination (Nejad et al., 2013).

3.3.3. Attention Control

Qualitative analysis revealed that attentional modulation, notably broadening present moment awareness rather than narrowing on difficult thoughts or feelings, was one of the benefits of MBCT (Chadwick et al, 2011). Another study found that a self-report measure of attention quantitatively improved following MBCT (Deckersbach et al, 2012).

Employing objective measures - electroencephalographic (EEG) and event related potential (ERP) - Howells et al (2012) measured differences at rest and during an attentional task between healthy controls and those with BD. They found that BD participants had significant frequency power abnormalities in the frontal and cingulate cortices, suggestive of decreased attentional readiness. They also found that BD was associated with ERP differences suggestive of non-relevant information processing over the frontal cortex. These aberrations from healthy controls diminished following MBCT, suggesting a positive effect on attentional control in BD.

3.3.4. Mood Regulation

A qualitative study found that, subjectively, BD participants reported improved ability to stabilize negative affects, and to reduce the impact of negative mood states after MBCT (Chadwick et al., 2011). Self-report measures of emotional regulation were collected in two studies and showed improvement after MBCT (Ives-Deliperi et al., 2013; Deckersbach et al., 2012), and which continued at 3-month follow-up (Deckersbach et al., 2012). One of these studies was an RCT and showed significant improvement relative to a waitlist control group (Ives-Deliperi et al., 2013).

Studies using objective measures of emotional processing and regulation also found evidence of significant effects of MBCT on these neural systems. Ives-Deliperi et al (2013) found that BD participants had significantly lower medial prefrontal cortical activation than controls, a deficit that has been hypothesized to be related to the impaired mood regulation in BD (Strakowski et al, 2012). Activation of this region increased significantly after MBCT, and improvement in mindfulness was positively correlated with this effect. One study measured event-related potentials (ERP) and heart-rate variability (HRV) as markers of emotional regulation (Howells et al, 2014). They found that, relative to controls, BD participants had alterations in both markers relative to controls, and these abnormalities were attenuated following MBCT. The authors reported that these markers can be considered indirect measures of emotional regulation via cortical-amygdala communication during emotional processing. Thus, MBCT appeared to improve emotional regulation as measured by autonomic tone and neural emotional processing.

3.3.5. Reward Processing

No studies address this facet.

3.3.6. Response Inhibition / Executive Function

One open-label study using self-report measures found that a 12-week MBCT intervention had a large significant effect on facets of executive function (Stange et al., 2011). However, there were multiple subscales examined, and for the impulsivity domain, it is notable that they did not find significant improvements in inhibition or emotional control. No BD MBCT studies utilized a specific response inhibition experimental paradigm.

3.3.7. Other Neuropsychological Facets

On self-report measures, Stange et al (2011) found improvements in working memory. Ives-Deliperi et al (2013) found significant improvements in neuropsychological tasks measuring working memory (digit span backwards), spatial memory (Rey Complex Figure recall), and verbal fluency (COWAT task). The former two of these findings were significantly poorer than healthy controls at baseline, suggesting a move towards ‘normalization’ after MBCT.

3.4. Practice

An analysis of the Perich et al (2013a) RCT found the amount of home meditation practice during the MBCT group intervention was correlated with improvements in depression measured at 1-year follow-up (Perich et al., 2013b). Moreover, those practicing 3 or more times a week were significantly more likely to have lower depression and anxiety scores at 12-month follow-up. However, studies such as Weber et al (2010) reported that only a minority of their participants subjectively perceived home practice as useful. Mindful movement practices were more commonly practiced than the traditional sitting or body scan meditation by people with BD, and these moving mindfulness practices were the most likely to be continued after the formal group concluded until follow-up (Weber et al., 2010). It is also notable that the positive trial by Deckersbach et al (2012) used a modified MBCT that was longer (12 weeks), arguably providing more of an opportunity for practice, and had more emphasis on movement practices. In their retrospective survey of past participants, the majority of whom had participated in MBCT over 2 years ago, Weber et al (2017) found a majority (54%) still practiced weekly, although for 30 minutes or less. Furthermore, those who practiced the briefest formal practice-the three-minute breathing space-at least weekly were more likely to report perceived benefit in prevention of relapse in depression than those who practiced it less frequently. This was the only formal practice with any association with perceived clinical effect.

In MBCT trials, attrition results in lower practice doses and it was a problem in several trials. The trial that had the lowest completion rate (58%) was of perinatal women with bipolar spectrum disorders (BDI, II, NOS, and cyclothymia) (Miklowitz et al., 2015). There were likely a number of factors that contributed to this high attrition rate, including the stressors and multiple demands particular to this time of life, compounded by the challenges with affect regulation inherent in these disorders, and the fact that the majority of women were not on medication (likely due to concerns for the fetus). The women in the study with unipolar depression were also mostly not on medication but had a much higher completion rate (93%). They also found that higher YMRS scores at entry were associated with poorer attendance (mean for those with < 4 classes = 5.86 (SD=4.18); >/=4 classes = 1.41 (SD=1.72). Another study (Miklowitz et al., 2009) found that non-completers were more likely to be younger than completers (mean of 29 versus 48 years, respectively). In summary, younger age, lack of medication related to perinatal status, and higher mania scores at entry were associated with higher attrition in MBCT for BD, thus leading to lower MBCT ‘dosage’.

Perich et al (2013b) found that participants with more mood episodes were less likely to practice. Participants have cited challenges in practicing mindfulness when experiencing low mood which seemed to decrease their motivation to do so (Chadwick et al., 2011). They also discussed the importance of flexibility depending on mood state - i.e. engaging in more active practice when mood and energy were low (walking or mindfulness in daily life), and engaging in a seated, breath practice when energy is high so as to help slow things down and decenter from thoughts.

In sum, the amount of practice or MBCT dose appears to be an important potential mediator in BD. There is also some evidence that younger participants, those not on medication, and those with more severe illness (e.g. higher YMRS scores, or more episodes) may be less likely to practice or attend.

3.5. Overall Summary of Findings

Clinical findings are mixed for most symptom domains, often due to methodological issues. Even the largest, highest quality rated clinical study to date (Perich et al., 2013a; see Table 1), was underpowered by the authors’ calculations. MBCT does not appear to precipitate mania or increase manic symptoms, but there is not currently evidence to suggest that it decreases the risk of relapse. However, this question has not been sufficiently studied or powered. When clinically significant residual depressive symptoms were present, there was evidence of benefit in 2 of 3 studies. However, for both depressive and manic symptoms, the mood remission state of most participants at study entry created a floor effect, thus making it difficult to show significant improvement on already low symptom scores. Studies examining effects on anxiety had similar challenges, but there were a number of studies suggesting a positive effect. The suicidality effects need more study. The studies showing positive clinical effects seem to have been more robustly designed, and/or have provided a larger or more BD-specific MBCT ‘dose’.

Of the 6 core neurocognitive deficits of mood disorders synthesized by Malhi et al (2015), the evidence for MBCT is most compelling for its potential effects on attentional control and mood regulation. Reappraisal by way of decentering from negative thoughts – i.e. a facet of mindfulness – has also received empiric support at across multiple modes of investigation. However, in keeping with the mindfulness literature at large, self-report measurement of mindfulness can produce inconsistent results after mindfulness training (Bergomi et al., 2013). That said, it is also notable that all of the studies using the FFMQ were positive. Markers of frontal-executive control seem to be improved broadly post-MBCT, but the more BD-specific response inhibition marker needs to be examined. Rumination has received some support but needs more study. There are not yet studies examining the effect on MBCT on reward processing in BD.

The importance of practice and receiving a sufficient ‘dose’ of MBCT has also received support. However, mediation analysis is needed in larger studies.

4. Discussion

There is preliminary evidence of symptomatic and mechanistic improvements after MBCT for BD, and it appears to be well-tolerated. However, the state of the research is in its infancy, with only 3 small, underpowered RCTs, and 4 open-label trials to inform questions of clinical efficacy. This is supplemented with several studies exploring potential mechanisms. MBCT associated improvements in anxiety, depression, mood regulation, and broad attentional and frontal-executive control have the most evidence. Furthermore, other relevant mechanisms in mood disorders are also showing promise. However, there is not yet evidence of MBCT decreasing relapse or other relevant markers of disease course, such as hospitalization, as has been found in some other empirically studied psychotherapies for BD (Salcedo et al., 2016), or in MBCT for recurrent depression (Kuyken et al., 2016). A recent network meta-analysis of all psychosocial interventions for BD found that only those for family members reduced relapse rates (Chatterton et al., 2018). But there have not yet been adequately powered BD MBCT studies to test this proposition. From a mechanistic perspective, larger studies that also allow mediation analyses are also needed.

The broad themes of these findings are supported by a recent meta-analysis of mindfulness-based interventions (not specific to, but including, MBCT) for BD (Chu et al., 2018). They found significant within group (pre-post) effects for depression (moderate) and anxiety (small) clinically, and for mindfulness and attention. There was no significant change in mania within groups, and between groups effects were all non-significant, with evidence of high heterogeneity.

In considering future directions of research, the issue of potency and dose will have to be addressed. Building the capacity to decenter from maladaptive cognitions during moments of emotional turmoil is challenging within non-clinical populations engaging in mindfulness training. Therefore, it would be reasonable to anticipate that this training would be particularly challenging (while particularly beneficial) for individuals with psychopathology prominently involving impairments in executive functioning and emotional regulation. Notably, response inhibition has been shown to improve in non-clinical populations undergoing mindfulness training, but only in those who practiced the most (Allen et al., 2012). Thus, there is some suggestion from the collective body of research that tailoring MBCT to this population is important so that an adequate dosage is received. Possible modifications include: shorter practices, more emphasis on informal daily mindfulness, mindful movement practices, modifying the mindfulness practice based on the energy/mood level (i.e. sitting when high, movement when low), use of reminder technologies to practice formally or informally throughout the day and in between sessions, and more sessions (e.g. the 12-week manual developed by Deckersbach et al., 2012). Of note, there is evidence that mindful movement is the practice with the strongest correlation to mindfulness facets of non-judge and non-react (Carmody and Baer, 2008), which are the two of the facets most significantly associated with mood symptoms (Desrosiers et al., 2013). In the one study in our review that looked at these subscores of the FFMQ, these were 2 of the 3 that changed post-MBCT (Deckersbach et al., 2012). FFMQ, with its subscales, may be particularly sensitive to these qualities of mindfulness in meditators versus nonmeditators (or pre- versus post-MBCT), hence the finding of effect in BD studies using this scale and not others (Park et al., 2013).

With regards to modifications, the centrality of pharmacologic treatment in BD seems to suggest the importance of examining how best to integrate the management of medication with a mindfulness-based approach. Unfortunately, this consideration has been largely absent from clinical mindfulness research to date (Lovas et al., 2016). All but one of the studies in this review concerned patients that were on psychotropics, and the study involving patients largely off of their medications due to pregnancy was notably negative (Miklowitz et al., 2015). Pharmacologic treatment typically emphasizes treatment targets and symptom reduction, while mindfulness-based approaches explicitly guide patients away from control strategies with regards to their symptoms. While these may seem to be contrary treatment approaches, there is the potential to use mindfulness and self-compassion practices to improve how BD patients relate to many of the issues that arise when polypharmacy is the core intervention. A mindfulness approach may present a potential way to reduce medication exposure for comorbid symptoms, mitigate stigma, and thereby increase medication adherence to required mood stabilizers (Schuman-Olivier et al., 2013).

Future research also needs to address significant study quality issues. Mirroring the vast majority of psychotherapy research and clinical trials (Linden and Schermuly-Haupt, 2014), none of the studies identified in this review made a comprehensive attempt to measure adverse effects. Many of the studies did not assess for treatment fidelity (e.g. video-taped groups). All of the studies were underpowered or did not report power calculations.

Given the challenges in modifying the adult brain that has fully manifested the disorder, a promising line of research is exploring the use of MBCT to prevent the development of BD in high-risk youth. As anxiety disorders are often the first step in the developmental trajectory towards BD, one group has begun to study the use of MBCT in children with anxiety disorders and at least one parent with BD (Cotton et al., 2016; Strawn et al., 2016). Their initial open-label pilot trial of 10 youth demonstrated improved anxiety and emotional regulation after the 12-week MBCT intervention, which was modified for children (Cotton et al., 2016). The improvements in anxiety were associated with improvements in mindfulness (Cotton et al., 2016), and with functional activity changes in the anterior cingulate cortex, and anterior insula, in a related fMRI study (Strawn et al., 2016). Congruent with the results of the recent network meta-analysis noted above (Chatterton et al., 2017), the authors of this youth trial also postulated that building mindfulness skills in parent caregivers may be a fruitful direction.

MBCT holds promise as an adjunct to pharmacology for improving lives of patients with BD. However, modifications appear important so that participants have sufficient chance to learn this new strategy of being with thoughts and emotions.

4.1. Limitations

This systematic review does not quantify the effects through a meta-analysis. We did not feel meta-analysis was indicated since the quality of the studies to date were low and the review revealed a paucity of RCTs. In a random-effects meta-analysis, these low numbers can lead to high heterogeneity, which calls the utility of the exercise into question (Higgins et al., 2003). The recent meta-analysis of mindfulness-based interventions for BD found the anticipated high heterogeneity of over 75% and non-significant between groups effects (Chu et al, 2018). However, a narrative synthesis can potentially over or under represent effects that a statistical synthesis might capture. When additional high-quality data from RCTs with active attention-matched controls are available, a meta-analysis would be useful. Without active controls, even RCTs can be misleading as they do not control for common factors, such as group effects/cohesion, etc.

4.2. Conclusion

Further well-powered clinical trials with active attention-matched controls are needed to establish the efficacy of MBCT for BD. Preliminary clinical and mechanistic findings are promising. Early studies identify several modifications to MBCT that may increase the likelihood of success as well as several baseline clinical predictors of attrition for people with BD participating in MBCT, which should be controlled for in future trials.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Allen M, Dietz M, Blair KS, van Beek M, Rees G, Vestergaard-Poulsen P, Lutz A, Roepstorff A, 2012. Cognitive-Affective Neural Plasticity following Active-Controlled Mindfulness Intervention. J. Neurosci 32, 15601–15610. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2957-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashok AH, Marques TR, Jauhar S, Nour MM, Goodwin GM, Young AH, Howes OD, 2017. The dopamine hypothesis of bipolar affective disorder: the state of the art and implications for treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 22, 666–679. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergomi C, Tschacher W, Kupper Z, 2013. The Assessment of Mindfulness with Self-Report easures: Existing Scales and Open Issues. Mindfulness (N. Y). 4, 191–202. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0110-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berk M, Parker G, 2009. The Elephant on the Couch: Side-Effects of Psychotherapy. Aust. New Zeal. J. Psychiatry 43, 787–794. doi: 10.1080/00048670903107559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos EH, Merea R, van den Brink E, Sanderman R, Bartels-Velthuis AA, 2014. Mindfulness training in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample: Outcome evaluation and comparison of different diagnostic groups. J. Clin. Psychol 70, 60–71. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, Grow J, Chawla N, Hsu SH, Carroll HA, Harrop E, Collins SE, Lustyk MK, Larimer ME, 2014. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 547–556. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas SA, Kassem L, Brotman MA, Leibenluft E, McMahon FJ, 2016. Neurocognitive functioning in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder and unaffected relatives: A review of the literature. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 69,193–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J, Baer RA, 2008. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J. Behav. Med 31, 23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick P, Kaur H, Swelam M, Ross S, Ellett L, 2011. Experience of mindfulness in people with bipolar disorder: A qualitative study. Psychother. Res 21, 277–285. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2011.565487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Luberto CM, Sears RW, Strawn JR, Stahl L, Wasson RS, Blom TJ, Delbello MP, 2016. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for youth with anxiety disorders at risk for bipolar disorder: a pilot trial. Early Interv. Psychiatry 10, 426–34. doi: 10.1111/eip.12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD, 2017. Mindfulness Interventions. Annu. Rev. Psychol 68, 491–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-042716-051139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckersbach T, Hölzel BK, Eisner LR, Stange JP, Peckham AD, Dougherty DD, Rauch SL, Lazar S, Nierenberg AA, 2012. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for nonremitted patients with bipolar disorder. CNS Neurosci. Ther 18, 133–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00236.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers A, Klemanski DH, Nolen-Hoeksema S, 2013. Mapping Mindfulness Facets Onto Dimensions of Anxiety and Depression. Behav. Ther 44, 373–384. doi: 10.1016/J.BETH.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson T, Becerra R, Coombes J, 2017. Executive functioning deficits among adults with Bipolar Disorder (types I and II): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord 218, 407–427. doi: 10.1016/J.JAD.2017.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SH, Black N, 1998. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 52, 377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland E, Gaylord S, Park J, 2009. The Role of Mindfulness in Positive Reappraisal. Explor. J. Sci. Heal 5, 37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2008.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO, 2015. Neurophysiological evidence for remediation of reward processing deficits in chronic pain and opioid misuse following treatment with Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement: exploratory ERP findings from a pilot RCT. J. Behav. Med 38, 327–336. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9607-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland EL, Gaylord SA, Fredrickson BL, 2011. Positive Reappraisal Mediates the Stress-Reductive Effects of Mindfulness: An Upward Spiral Process. Mindfulness (N. Y). 2, 59–67. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0043-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert K, Gruber J, 2014. Emotion Regulation of Goals in Bipolar Disorder and Major Depression: A Comparison of Rumination and Mindfulness. Cognit. Ther. Res 38, 375–388. doi: 10.1007/s10608-014-9602-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, Hammen C, 1995. Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 152, 1635–1640. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K, 2015. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Geddes JR, Tunbridge EM, 2018. The Emerging Neurobiology of Bipolar Disorder. Trends Neurosci. 41, 18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Hofmann SG, 2017. The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care. World Psychiatry 16, 245–246. doi: 10.1002/wps.20442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeren A, Philippot P, 2011. Changes in Ruminative Thinking Mediate the Clinical Benefits of Mindfulness: Preliminary Findings. Mindfulness (N. Y). 2, 8–13. doi: 10.1007/s12671-010-0037-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, 2003. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 327, 557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, Metcalf CA, Morris LK, Robinaugh DJ, Worthington JJ, Pollack MH, Simon NM, 2013. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74, 786–92. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U, 2011. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect. Psychol. Sci doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells FM, Ives-Deliperi VL, Horn NR, Stein DJ, 2012. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy improves frontal control in bipolar disorder: a pilot EEG study. BMC Psychiatry 12, 15. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howells FM, Laurie Rauch HG, Ives-Deliperi VL, Horn NR, Stein DJ, 2014. Mindfulness based cognitive therapy may improve emotional processing in bipolar disorder: pilot ERP and HRV study. Metab. Brain Dis 29, 367–375. doi: 10.1007/s11011-013-9462-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ives-Deliperi VL, Howells F, Stein DJ, Meintjes EM, Horn N, 2013. The effects of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: a controlled functional MRI investigation. J. Affect. Disord 150, 1152–1157. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.05.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, Pincus HA, Shad M, Salloum I, Conigliaro J, Haas GL, 2004. Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 6, 368–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00138.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Yu BH, Lee DS, Kim J-H, 2012. Ruminative response in clinical patients with major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and anxiety disorders. J. Affect. Disord 136, e77–e81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjærrstad HL, Vinberg M, Goldin PR, Køster N, Støttrup MMD, Knorr U, Kessing LV, Miskowiak KW, 2016. Impaired down-regulation of negative emotion in self-referent social situations in bipolar disorder: A pilot study of a novel experimental paradigm. Psychiatry Res. 238, 318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.02.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, Byng R, Dalgleish T, Kessler D, Lewis G, Watkins E, Brejcha C, Cardy J, Causley A, Cowderoy S, Evans A, Gradinger F, Kaur S, Lanham P, Morant N, Richards J, Shah P, Sutton H, Vicary R, Weaver A, Wilks J, Williams M, Taylor RS, Byford S, 2015. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 386, 63–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken W, Warren FC, Taylor RS, Whalley B, Crane C, Bondolfi G, Hayes R, Huijbers M, Ma H, Schweizer S, Segal Z, Speckens A, Teasdale JD, Van Heeringen K, Williams M, Byford S, Byng R, Dalgleish T, 2016. Efficacy of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in prevention of depressive relapse an individual patient data meta-analysis from randomized trials. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 565–574. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden M, 2013. How to Define, Find and Classify Side Effects in Psychotherapy: From Unwanted Events to Adverse Treatment Reactions. Clin. Psychol. Psychother 20, 286–296. doi: 10.1002/cpp.1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden M, Schermuly-Haupt ML, 2014. Definition, assessment and rate of psychotherapy side effects. World Psychiatry. doi: 10.1002/wps.20153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovas DA, Lutz J, Schuman-Olivier Z, 2016. Meditation and medication-what about a middle path? JAMA Psychiatry 73. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhi GS, Byrow Y, Fritz K, Das P, Baune BT, Porter RJ, Outhred T, 201 . Bipolar Disord. 17, 3–20. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Alatiq Y, Goodwin GM, Geddes JR, Fennell MJV, Dimidjian S, Hauser M, Williams JMG, 2009. A pilot study of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder. Int. J. Cogn. Ther 2, 373–382. doi: 10.1521/ijct.2009.2.4.373 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miklowitz DJ, Semple RJ, Hauser M, Elkun D, Weintraub MJ, Dimidjian S, 2015. Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy for Perinatal Women with Depression or Bipolar Spectrum Disorder. Cognit. Ther. Res 590–600. doi: 10.1007/s10608-015-9681-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nejad AB, Fossati P, Lemogne C, 2013. Self-referential processing, rumination, and cortical midline structures in major depression. Front. Hum. Neurosci 7, 666. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick DM, Swartz HA, Frank E, 2010. Suicide attempts in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder: A review and meta-analysis of the evidence. Bipolar Disord. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00786.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park T, Reilly-Spong M, Gross CR, 2013. Mindfulness: a systematic review of instruments to measure an emergent patient-reported outcome (PRO). Qual. Life Res 22, 2639–59. doi: 10.1007/s11136-013-0395-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perich T, Manicavasagar V, Mitchell PB, Ball JR, 2013. The association between meditation practice and treatment outcome in Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for bipolar disorder. Behav. Res. Ther 51, 338–43. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perich T, Manicavasagar V, Mitchell PB, Ball JR, 2011. Mindfulness, response styles and dysfunctional attitudes in bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perich T, Manicavasagar V, Mitchell PB, Ball JR, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, 2013. A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr. Scand 127, 333–343. doi: 10.1111/acps.12033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinares M, Sánchez-Moreno J, Fountoulakis KN, 2014. Psychosocial interventions in bipolar disorder: what, for whom, and when. J. Affect. Disord 156, 46–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahdra BK, MacLean KA, Ferrer E, Shaver PR, Rosenberg EL, Jacobs TL, Zanesco AP, King BG, Aichele SR, Bridwell DA, Mangun GR, Lavy S, Alan Wallace B, Saron CD, MacLean KA, 2009. Enhanced Response Inhibition During Intensive Meditation Training Predicts Improvements in Self-Reported Adaptive Socioemotional Functioning. Mindfulness (N. Y). Neff doi: 10.1037/a0022764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo S, Gold AK, Sheikh S, Marcus PH, Nierenberg AA, Deckersbach T, Sylvia LG, 2016. Empirically supported psychosocial interventions for bipolar disorder: Current state of the research. J. Affect. Disord 201, 203–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Noordsy DL, Brunette MF, 2013. Strategies for Reducing Antipsychotic Polypharmacy. J. Dual Diagn 9, 208–218. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2013.778767 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silveira É Jr. de M, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, 2015. Rumination in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr 37, 256–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2014-1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, Sachs GS, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Pollack MH, 2004. Anxiety Disorder Comorbidity in Bipolar Disorder Patients: Data From the First 500 Participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD). Am. J. Psychiatry 161, 2222–2229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stange JP, Eisner LR, Hölzel BK, Peckham AD, Dougherty DD, Rauch SL, Nierenberg AA, Lazar S, Deckersbach T, 2011. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: effects on cognitive functioning. J. Psychiatr. Pract 17, 410–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000407964.34604.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawn JR, Cotton S, Luberto CM, Patino LR, Stahl LA, Weber WA, Eliassen JC, Sears R, DelBello MP, 2016. Neural Function Before and After Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy in Anxious Adolescents at Risk for Developing Bipolar Disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol 26, 372–9. doi: 10.1089/cap.2015.0054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, 2010. The strong relationship between bipolar and substance-use disorder. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1187, 276–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05146.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y-Y, Hölzel BK, Posner MI, 2015. The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 16, 213–225. doi: 10.1038/nrn3916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troy AS, Shallcross AJ, Mauss IB, 2013. A Person-by-Situation Approach to Emotion Regulation. Psychol. Sci 24, 2505–2514. doi: 10.1177/0956797613496434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dam NT, van Vugt MK, Vago DR, Schmalzl L, Saron CD, Olendzki A, Meissner T, Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Gorchov J, Fox KCR, Field BA, Britton WB, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Meyer DE, 2018. Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci 13, 36–61. doi: 10.1177/1745691617709589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vugt MK, Hitchcock P, Shahar B, Britton W, 2012. The Effects of Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy on Affective Memory Recall Dynamics in Depression: A Mechanistic Model of Rumination. Front. Hum. Neurosci 6, 257. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber B, Jermann F, Gex-Fabry M, Nallet A, Bondolfi G, Aubry J-M, 2010. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: a feasibility trial. Eur. Psychiatry 25, 334–337. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2010.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]