Abstract

We tested a prevention approach aimed at reducing growth in alcohol use in middle school using four waves (2 years) of data from a cluster randomized trial (N = 15 middle schools, 1,890 students, 47.1% female, 75.2% White). Our approach exposed students to a broad cross-section of peers through collaborative, group-based learning activities in school (i.e., cooperative learning). We hypothesized that the increased social contact created by cooperative learning would promote greater peer relatedness, interrupting the process of deviant peer clustering and, in turn, reduce escalations in alcohol use. Our results supported these hypotheses, suggesting that the social nature of cooperative learning, and the emphasis on group work and collaboration, can provide social and behavioral as well as academic benefits for students.

Keywords: alcohol use, deviant peer affiliation, peer relatedness, cooperative learning, middle school

Developmental pathways that lead to problematic alcohol and other drug use in adulthood emphasize early adolescence as a key window of risk. Youth who initiate alcohol and other drug use before age 15 are at elevated risk for abuse and dependence later in adolescence and adulthood (Dawson et al., 2008; Hingson & Zha, 2009; Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2014). In turn, problematic alcohol and drug use are key risk factors for injury and premature death (WHO, 2014), as well as greater risk of preventable diseases, such as cirrhosis of the liver, diabetes, and cancer (Rehm et al., 2009).

In exploring the etiology of alcohol use and related behavioral problems, researchers have found that peer influence plays a major role. Specifically, research has linked peer influence with a wide variety of negative behaviors in adolescence, including alcohol and other drug use and abuse, antisocial and violent behavior, and high-risk sexual behavior (Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2013, 2014; Van Ryzin, Johnson, Leve, & Kim, 2011; for review, see Dishion & Patterson, 2006). Peer influence is particularly strong in early adolescence, when peer acceptance is critical to well-being and the influence of parents begins to wane (Steinberg & Morris, 2001).

Early adolescents who lack well-developed social skills can be socially marginalized or rejected by others in middle school. Socially rejected youth tend to affiliate with one another (i.e., deviant peer clustering; Dishion et al., 1991; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989), and within these clusters, delinquent behavior is reinforced through peer pressure, modeling, facilitation, and expressions of approval (i.e., deviancy training; Granic & Dishion, 2003; Van Ryzin & Dishion, 2013). Indeed, deviant peer clustering is one of the strongest predictors of multiple forms of problem behavior in adolescence (Haynie & Osgood, 2005). The focus of this paper is on links between deviant peer clustering and alcohol use, which have been found from early adolescence to early adulthood (Dishion & Owen, 2002; Fergusson, Swain-Campbell, & Horwood, 2002; Van Ryzin, Fosco, & Dishion, 2012).

Prevention of Early Adolescent Alcohol Use

A variety of prevention approaches have been applied to interrupt deviant peer clustering and reduce adolescent alcohol and other drug use. A common approach among school-based prevention programs is to ask teachers or school counselors to deliver psychosocial content aimed at changing attitudes, normative beliefs, and/or peer resistance skills related to use of alcohol and other drugs. Although research has found these programs to be effective, meta-analyses have found generally small effects (i.e., mean ES = .05 in Wilson et al., 2001; median ES =.13 in Tobler et al., 2000; OR = .70 to .80 in MacArthur et al., 2016). Another strategy that has received attention is the use of “peer leaders” as agents of positive behavioral change, although the results of such programs have been mixed (e.g., Valente et al., 2007).

In this project, we took a different approach; we attempted to interrupt the process of deviant peer clustering and reduce alcohol use by exposing youth to a broad cross-section of their peers through collaborative, group-based learning activities in school (i.e., cooperative learning). In addition to their instructional purpose, these group-based learning activities can increase social opportunities for youth and to provide a mechanism by which socially marginalized youth can develop positive relationships with more prosocial peers. In this way, we hoped to interrupt the process of deviant peer clustering and reduce the prevalence of negative, antisocial peer influences. Specifically, we investigated whether cooperative learning could enhance peer relations among students and, in turn, reduce deviant peer clustering, which would then reduce escalations in alcohol use.

Positive Interdependence and Peer Relations

In cooperative learning, positive social experiences are created by placing students in learning groups under conditions of positive interdependence, where individual goals are aligned with the goals of the group such that individual success promotes group success and vice versa. Cooperative learning provides many ways in which a teacher may implement interdependence. For example, teachers may implement goal interdependence, in which they require a single finished product from a group, and/or reward interdependence, in which they offer a reward to the group if everyone achieves above a certain threshold on an end-of-unit assessment. The lesson may specify a unique set of materials (resource interdependence), roles (role interdependence), or tasks (task interdependence) for each student in a group, such that the students have to collaborate with one another in order to finish the lesson. Different forms of positive interdependence can be used simultaneously in a single lesson, increasing the incentive for students to cooperate.

When learning goals are structured cooperatively under positive interdependence, students tend to interact in ways that promote goal attainment of others in the group, such as providing instrumental and emotional support, and sharing information and resources (Johnson, Johnson & Maruyama, 1983). The positive feelings that arise from these collaborative, supportive interactions tend to be transferred to the group members who helped to promote one’s success, resulting in a “benign spiral” that further increases positive social interactions and promotes positive peer relations (Deutsch, 1949, 1962; Roseth et al., 2008).

We used the Johnsons’ version of cooperative learning (Johnson, Johnson, & Holubec, 2013), which also asks teachers to reinforce the use of positive social skills by observing student interactions during learning activities and recording the number of times that students exhibit particular kinds of positive, helpful behavior. In addition, after the lesson is complete, students are instructed to find something specific and positive to say about each other student’s contribution to the group’s performance, further cementing the positive peer relations that arose during the lesson.

Current Project

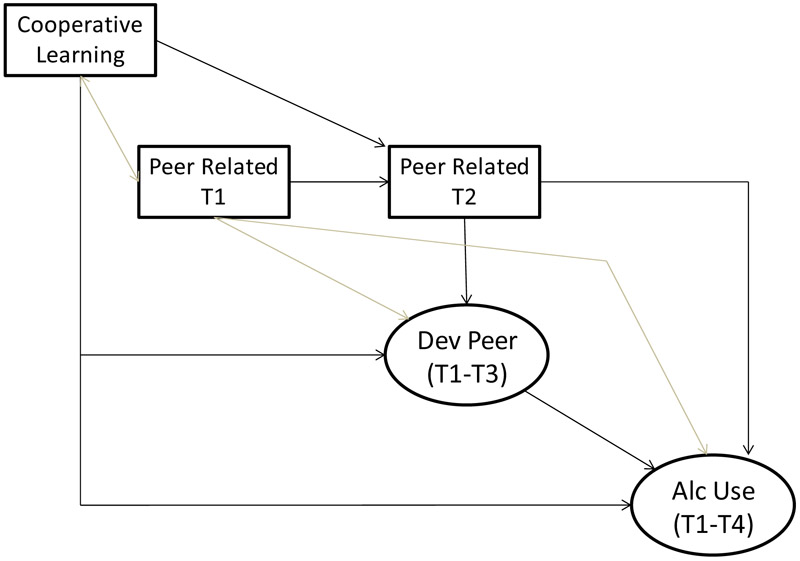

In previous research, cooperative learning has been found to have significant effects on adolescent alcohol use over one year (i.e., two waves of data), with moderate to large effects (Van Ryzin & Roseth, 2018a, 2018b). In this study, we aimed to explore mediating mechanisms using the developmental pathway described above. Given the focus on social contact, the development of social skills, and positive peer relations, we hypothesized that cooperative learning would promote greater peer relatedness among students, which would reduce deviant peer affiliation and, in turn, reduce alcohol use. The conceptual model is shown in Figure 1. To ensure temporal precedence in our mediational model, we used the intervention condition (i.e., cooperative learning) to predict change in peer relatedness by wave 2, which predicted change in deviant peer affiliation by wave 3, which in turn predicted change in alcohol use by wave 4. To obtain more accurate measures of change across three and four waves, respectively, growth curve slopes are modeled for deviant peer affiliation and alcohol use (growth curves were not an option for peer relatedness when only the first two waves of data were used). Intercepts (and baseline levels of peer relatedness) were allowed to correlate freely with each other and with the intervention condition.

Figure 1.

Full model. Peer Related = Peer Relatedness. Dev Peer = Deviant Peer Affiliation. Alc Use = Alcohol Use. Latent constructs (i.e., the ovals) are linear growth curve slopes; models also included intercept terms (not pictured), which were allowed to correlate freely with each other and with the intervention condition (i.e., cooperative learning). Baseline levels of Peer Relatedness were also allowed to correlate with the intervention condition. Key model paths are in black, and control paths are in gray.

Method

All aspects of this study were approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the Oregon Research Institute. This study was registered as trial NCT03119415 in ClinicalTrials.gov under Section 801 of the Food and Drug Administration Amendments Act.

Sample

The sample was derived from a small-scale randomized trial of cooperative learning in 15 rural middle schools in the Pacific Northwest. Schools were matched based upon size and demographics (e.g., free/reduced lunch percentage) and randomized to condition (i.e., intervention vs. waitlist control). We were concerned about the likelihood of losing schools assigned as controls, so we randomized an extra school to this condition (i.e., 8 waitlist-control vs. 7 intervention schools).

Our analytic sample included N = 1,890 students who enrolled in the project during the 2016-2017 or 2017-2018 school years. In the first year of the project, we only enrolled 7th graders, and in the second year we assessed these students as 8th graders (we enrolled any additional 8th graders who were not originally a part of the study). We achieved greater than 80% student participation at each data collection point by using a passive consent procedure and providing research staff to oversee the data collection. We also offered compensation to the schools for participating in the project, and enrolled participating students in a prize raffle. Student demographics by school are reported in Table 1. Overall, the sample was 47.1% female (N = 890) and 75.2% White (N = 1,421). Other racial/ethnic groups included Hispanic/Latino (13.2%, N = 249), multi-racial (5.3%, N = 100), and American Indian/Alaska Native (3.1%, N = 58); our sample included less than 1% Asian, African-American, and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. Overall, 13.9% (N = 262) were reported as having Special Ed status, 78.6% (N = 1486) did not have Special Ed status, and 7.5% (N = 142) were missing a Special Ed designation. Free-and-reduced-price lunch (FRPL) status was not made available by the schools, although school-level FRPL figures (obtained from state records) are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive data by school

| School | Intervention | N | % female | % White | % Special Ed | % FRPLa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | 282 | 47.9 | 73.0 | 11.7 | 53 |

| 2 | Yes | 61 | 52.5 | 75.4 | 16.4 | 66 |

| 3 | Yes | 110 | 40.0 | 60.9 | n/a | 62 |

| 4 | No | 114 | 47.4 | 93.0 | 24.6 | 65 |

| 5 | Yes | 112 | 50.0 | 83.0 | 15.2 | 72 |

| 6 | Yes | 121 | 47.1 | 90.1 | 19.8 | 71 |

| 7 | No | 53 | 41.5 | 92.5 | 18.9 | 33 |

| 8 | Yes | 105 | 46.7 | 78.1 | 10.5 | 57 |

| 9 | No | 71 | 45.1 | 81.7 | 19.7 | 45 |

| 10 | Yes | 84 | 33.3 | 72.6 | 4.8 | 95 |

| 11 | No | 183 | 44.8 | 65.0 | 17.5 | 61 |

| 12 | No | 239 | 51.0 | 48.5 | 13.0 | 84 |

| 13 | No | 197 | 49.2 | 90.4 | 11.7 | 66 |

| 14 | No | 50 | 48.0 | 88.0 | 16.0 | 39 |

| 15 | No | 108 | 51.9 | 80.6 | 15.7 | 46 |

State records.

Note. One school did not provide Special Ed status.

Procedure

Training for intervention school staff began in the fall of 2016 and continued throughout the 2016-2017 school year, consisting of 3 half-day in-person sessions, periodic check-ins via videoconference, and access to resources (e.g., newsletters). The three in-person training sessions per school were conducted in (1) late September and early October, (2) late October through early December, and (3) late January through late March. Where possible, we included the entire staff in each training session; occasionally scheduling or other restrictions did not permit access to the entire staff, but there were teachers representing 6th, 7th, and 8th grades in each training session. These sessions were conducted by D. W. and R. T. Johnson, supported by the authors, and utilized Cooperation in the Classroom, 9th Edition by Johnson, Johnson, and Holubec (2013); each staff member was given a copy of the book. Due to the geographic dispersal of the schools, each school received training individually according to their own schedule for professional development. Finally, we conducted a one-day administrator training during the summer of 2017, and a half-day follow-up training for teachers in the second year.

Under the Johnson’s approach, cooperative learning can include reciprocal teaching (e.g., Jigsaw), peer tutoring, collaborative reading, and other methods in which peers help each other learn in small groups under conditions of positive interdependence. The Johnsons’ approach also emphasizes individual accountability, explicit coaching in collaborative social skills, a high degree of face-to-face interaction, and the guided processing of group performance after the lesson is complete. Cooperative learning is viewed as a conceptual framework within which teachers can apply the basic concepts to design their own group-based activities using existing curricula. The training was not provided in a lecture format; rather, teachers were trained in cooperative learning through the use of cooperative learning techniques. At the conclusion of each training session, the trainers discussed how the lesson structure reflected the foundational concepts of cooperative learning, providing teachers with insight into how these concepts could be applied in their own teaching, as well as giving them a clear sense of what it feels like to participate in a cooperative learning lesson. At the end of the training session, teachers were provided the opportunity to develop draft lesson plans which they could use to deliver cooperative learning lessons in their own classroom.

Measures

Student data collection was conducted in schools during September/October and March/April of the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 school years (4 waves in total) using on-line surveys (i.e., Qualtrics; https://www.qualtrics.com/). To assess fidelity of implementation, we also conducted teacher observations. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained for these data from NIAAA (#CC-AA-17-011). To shrink the overall number of items and reduce participant burden, existing data from other studies were used to select the highest-loading items from each scale below (additional information available from the first author).

Peer relatedness.

We used 4 items from the Relatedness Scale, which has been used in previous research as a predictor of positive school adjustment in adolescents (Furrer & Skinner, 2003). Items included “When I’m with my classmates, I feel accepted” and “When I’m with my classmates, I feel unimportant” (reverse scored). Students responded on a 4-point scale from 1 (Not at all true) to 4 (Very true). Items were averaged to arrive at the scale score. Alpha reliability was .71 at wave 1 and .79 at wave 2.

Deviant peer affiliation.

Students reported on the frequency in the last month with which they associated with other youth who engaged in delinquent activities, including “get in trouble a lot”, “fight a lot”, “take things that don’t belong to them”, and “skip school” (4 items overall). Students responded on a 5-point scale from 0 (Never) to 4 (7 or more times). Items were averaged to arrive at the final scores. Alpha reliability was between .76 and .84 for Waves 1-3.

Alcohol use.

Students reported on their use of alcohol in the last month using the following scale: No use = 1, Occasionally (1-3 times) = 2, Fairly often (4-6 times) = 3, Regularly (7-9 times) = 4, and All the time (10+ times) = 5. At baseline, 95.8% of students (N = 1,392) reported no alcohol use, but by wave 4, the percentage of students reporting no use had declined to 78.9% (N = 1,168).

Demographics.

Sex was collected from school records and coded as Male (0) vs. Female (1).

Observed intervention fidelity.

Research staff blind to intervention assignment observed teaching practices in intervention and control schools. We trained our observers to adequate reliability using simulated data before they were permitted to conduct observations in actual classrooms, and we used an established observation protocol for key aspects of cooperative learning (e.g., positive interdependence; Krol, Sleegers, Veenman, & Voeten, 2008; Veenman et al., 2002). Observations were conducted in the late fall/early winter and in the spring. Classrooms were selected for observation at random, and observers remained in a classroom for an entire class period.

Analysis Plan

A test of mediation traditionally includes an initial direct-effects model that tests the path between the predictor and outcome (commonly referred to as “path c”), followed by a mediation model in which the following paths are tested: the predictor to the presumed mediator (“path a”), the mediator to the outcome (“path b”), and the combined indirect effect of the predictor on the outcome via the mediator, while controlling for the direct effect (commonly referred to as “path c-prime”; Judd, Kenny, & McClelland, 2001; MacKinnon & Dwyer, 1993).

Thus, we initially tested a direct-effects model for alcohol use (referred to in the Results section as “Model 1”). We used all four waves of measurement in a latent growth curve and evaluated intervention effects on the linear slope (i.e., the change in alcohol use during the project). Next, we evaluated deviant peer affiliation as a mediator of these effects using linear growth curve terms that included the first three waves of measurement (i.e., Model 2). To test mediation, we calculated the indirect effects of the intervention on alcohol use by means of deviant peer affiliation. Finally, we added peer relatedness to the model as a mediator of intervention effects on deviant peer affiliation, and tested the indirect pathway (i.e., Model 3). We used peer relatedness from wave 2, controlling for wave 1 levels, to represent change, as two time points are not sufficient to create a latent growth curve. The full model (i.e., Model 3) is represented in Figure 1. At each step, we tested for sex differences. All linear growth curve slopes were regressed on the corresponding intercept terms, and intercept terms (and baseline scores for peer relatedness) were allowed to correlate with each other and with the intervention condition.

We fit these models and calculated the significance of the indirect effects using Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation with robust standard errors, which can provide unbiased estimates in the presence of missing data and/or non-normal or skewed distributions (Enders & Bandalos, 2001). Mplus also enabled us to account for the nesting in the data and calculate appropriate standard errors; however, sample size limitations prevented us from including random effects in the model, so all effects were fixed. For each model, standard measures of fit are reported, including the chi-square (χ2), comparative fit index (CFI), nonnormed or Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI values greater than .95, TLI values greater than .90, and RMSEA values less than .05 indicate good fit (Bentler, 1990; Bentler & Bonett, 1980; Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive data for all variables and correlations are presented in Table 2. Female students reported lower levels of relatedness at waves 1 and 2 (r = −.05 and −.11, respectively) and lower levels of deviant peer affiliation at wave 1 (r = −.08); all other sex differences were non-significant.

Table 2.

Correlations and descriptive data (Level 1)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Peer Relatedness (W1) | — | |||||||||

| 2. Peer Relatedness (W2) | .50*** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Deviant Peer Affiliation (W1) | −.25*** | −.12*** | — | |||||||

| 4. Deviant Peer Affiliation (W2) | −.14*** | −.27*** | .42*** | — | ||||||

| 5. Deviant Peer Affiliation (W3) | −.12*** | −.07** | .36*** | .46*** | — | |||||

| 6. Alcohol Use (W1) | −.05* | −.01 | .29*** | .24*** | .12*** | — | ||||

| 7. Alcohol Use (W2) | −.10*** | −.20*** | .28*** | .42*** | .19*** | .49*** | — | |||

| 8. Alcohol Use (W3) | −.06* | −.05 | .23*** | .32*** | .48*** | .22*** | .35*** | — | ||

| 9. Alcohol Use (W4) | −.05 | −.05 | .21*** | .29*** | .30*** | .13*** | .26*** | .36*** | — | |

| 10. Sex | −.05* | −.11*** | −.08** | −.02 | −.01 | −.04 | −.02 | .03 | −.03 | — |

| N | 1447 | 1513 | 1453 | 1532 | 1569 | 1453 | 1534 | 1569 | 1481 | 1856 |

| M | 3.07 | 2.97 | 1.44 | 1.50 | 1.54 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.27 | 1.34 | .48 |

| SD | .68 | .76 | .62 | .67 | .74 | .41 | .61 | .73 | .81 | - |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

ANOVA models indicated that students in intervention and control schools did not differ in terms of baseline levels of alcohol use [F(1, 1451) = 1.47, ns], or peer relatedness [F(1,1445) = .04, ns]. The two groups did differ in terms of deviant peer affiliation [F(1,1451) = 3.97, p < .05], with control schools higher than intervention schools, but this effect was very small, R2 < .01. Means and group comparisons for all variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Group differences for key outcomes

| Variable |

M (control) |

M (intervention) |

ANOVA |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Peer Relatedness (W1) | 3.07 | 3.08 | F(1,1445) = .04, ns |

| 2. Peer Relatedness (W2) | 2.89 | 3.06 | F(1,1511) = 20.15, p < .001 |

| 3. Deviant Peer Affiliation (W1) | 1.47 | 1.41 | F(1,1451) = 3.97, p = .046 |

| 4. Deviant Peer Affiliation (W2) | 1.60 | 1.40 | F(1,1530) = 33.14, p < .001 |

| 5. Deviant Peer Affiliation (W3) | 1.61 | 1.45 | F(1,15671) = 17.39, p < .001 |

| 6. Alcohol Use (W1) | 1.08 | 1.06 | F(1, 1451) = 1.47, ns |

| 7. Alcohol Use (W2) | 1.23 | 1.10 | F(1, 1532) = 16.02, p < .001 |

| 8. Alcohol Use (W3) | 1.34 | 1.19 | F(1, 1567) = 16.60, p < .001 |

| 9. Alcohol Use (W4) | 1.41 | 1.27 | F(1, 1479) = 10.77, p = .001 |

With regards to fidelity observations, ANOVA indicated significantly higher levels of observed positive interdependence in intervention schools as compared to control schools in the spring of the first year, F(1,98) = 10.79, p < .01, R2 = .10. Fidelity observations at baseline demonstrated no differences, F(1,99) = 1.41, ns.

We first evaluated the direct effects of cooperative learning on change (i.e., slope) in alcohol use (i.e., path c). Model fit was adequate, χ2(8) = 8.54, ns; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = .006 (90% C.I.: .000-.028). Results are provided in Table 4 (see Model 1). Intervention effects on change in alcohol use were significant and small to moderate. Sex differences were not significant, χ2(1) = 2.74, ns.

Table 4.

Model effects

| Model path | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperative learning → Alcohol Use (Slope) | −.17*** | −.03 | −.03 |

| Cooperative learning → Deviant Peers (Slope) | −.18* | −.11 | |

| Deviant Peers (Slope) → Alcohol Use (Slope) | .90*** | .88*** | |

| Cooperative learning → Peer Related (T2) | .19*** | ||

| Peer Related (T1) → Peer Related (T2) | .43*** | ||

| Peer Related (T2) → Deviant Peers (Slope) | −.31*** | ||

| Peer Related (T2) → Alcohol Use (Slope) | −.10† |

p = .056.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

We next evaluated intervention effects with the mediator (i.e., change in deviant peer affiliation) included. Model fit was adequate, χ2(21) = 107.74, p < .001; CFI = .95; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .047 (90% C.I.: .038-.056). Results are provided in Table 4 (see Model 2). The effects of cooperative learning on change in deviant peer affiliation were significant, and the indirect effect of cooperative learning on alcohol use by means of deviant peer affiliation was significant (standardized effect = −.17, p < .05). The direct effect of cooperative learning on change in alcohol use was no longer significant, suggesting full mediation. Sex differences were not significant, χ2(5) = 4.29, ns.

Finally, we added relatedness to the model as a mediator of effects on change in deviant peer affiliation. Model fit was adequate, χ2(32) = 152.56, p < .001; CFI = .95; TLI = .93; RMSEA = .044 (90% C.I.: .038-.052). Results are provided in Table 4 (see Model 3). Cooperative learning predicted significant growth in peer relatedness, which in turn significantly and negatively predicted change in deviant peer affiliation; the indirect effect was significant (standardized effect = −.06, p < .001). The effect of cooperative learning on change in deviant peer affiliation was no longer significant, suggesting full mediation. Sex differences were not significant, χ2(13) = 8.51, ns. Interestingly, the effect of peer relatedness on change in alcohol use was close to significance (p = .056).

Discussion

In this study, we found evidence supporting the hypothesized causal pathway from cooperative learning to alcohol use. First, we extended previous results that reported lower levels of alcohol use in schools using cooperative learning (Van Ryzin & Roseth, 2018a, 2018b); we found significant effects using 4 waves of data (2 years) instead of two waves (1 year) as in the previous research. Second, we found that the effects of cooperative learning on alcohol use were mediated by reductions in deviant peer affiliation across the first three waves. Finally, we found that the impact of cooperative learning on deviant peer affiliation was mediated by growth in peer relatedness across the first two waves. The experimental design of our trial provides strong internal validity for these results.

Our findings suggest that the social nature of cooperative learning, and the emphasis on group work and collaboration, can provide students with the opportunity to develop positive relationships with peers (i.e., peer relatedness), a finding that echoes previous research (Roseth et al., 2008). This implies that peer influences will not be exclusively antisocial in nature, which tends to occur when socially marginalized youth self-aggregate and establish antisocial behavioral norms (i.e., deviant peer clustering; Dishion et al., 1991). Instead, under cooperative learning, youth can develop relationships with more prosocial youth, reducing deviant peer affiliation. In turn, this change in the nature of their social influences can reduce escalations in alcohol use.

In addition to effects on deviant peer affiliation and alcohol use, there are many other salutary effects that can arise from more positive peer relations among early adolescents. For example, positive peer relations have been linked to increases in cognitive and affective empathy and, in turn, to reductions in bullying (Van Ryzin & Roseth, in press). Positive peer relations have also been linked to reductions in antisocial behavior and enhancements to academic engagement and achievement, self-esteem, and individual well-being among children of this age (Bukowski, 2003; Criss et al., 2002; Liem & Martin, 2011; Wentzel, 2005). This suggests that, rather than being viewed as an adjunct to educational goals (or worse, a distraction), a focus on positive peer relations should be considered a key mechanism by which to promote student achievement and adjustment, particularly in middle school when peer relations become developmentally important (Steinberg & Morris, 2001).

Interestingly, we found that the effects of peer relatedness on alcohol use were close to significance (p = .056), even when accounting for the influence of deviant peers. This suggests that there may be other mechanisms by which peer relations can impact alcohol use outside of the mediating mechanism of deviant peer affiliation. For example, loneliness, or a lack of social acceptance, can create risk for a variety of maladaptive outcomes, including depression, anxiety, eating disorders, and suicide ideation (Lasgaard, Goossens, Bramsen, Trillingsgaard, & Elklit, 2011; Vanhalst et al., 2012). Loneliness can even create significant risk for early mortality (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, 2015). Thus, it seems plausible that lack of social acceptance could be, by its very nature, a significant risk factor for alcohol use in adolescence, regardless of downstream impacts on peer affiliation and social influences. Future research should investigate this hypothesis.

Implications for Prevention

These results indicate that group-based learning activities in middle school, when implemented through cooperative learning, can have salutary effects on peer relations, which in turn can address some of the social processes that contribute to escalations in alcohol use. Cooperative learning has already been demonstrated to have far-reaching positive effects on academic motivation and achievement (Johnson, Johnson, Roseth, & Shin, 2014; Roseth et al., 2008), and can also reduce behavioral problems such as bullying and victimization (Van Ryzin & Roseth, 2018c, in press). In addition, cooperative learning does not require the purchase of specific prevention curricula or materials, and schools do not have to allocate instructional time for non-instructional purposes. Thus, cooperative learning represents a way for schools to improve instruction and student learning while simultaneously preventing student behavioral problems and improving school climate through the development of more positive peer relations.

Limitations and Conclusion

Although this research has many strengths, including a cluster randomized design and longitudinal data, it is limited in several ways. First, it is based upon a relatively homogeneous sample of rural students that was about three-quarters White, which limits the external validity (generalizability) of the results. Second, all student measures were self-report, which limits internal validity. Future research should consider additional data sources, such as teachers and/or parents, and more diverse populations. And third, the small number of schools in our sample (i.e., 15) limited the complexity of the models that we were able to fit to the data and may have prevented us from finding significant effects in some cases.

In spite of these weaknesses, this study contributes significantly to the literature on peer relations and alcohol use prevention in middle school. Our results suggest that adolescent alcohol use can be reduced through a series of positive social experiences with peers that are designed to enhance peer relations. These learning experiences can be designed and implemented by teachers to reflect local learning standards and content requirements, and do not require the purchase of outside curricula or materials as with traditional school-based alcohol and drug use prevention programs. Thus, we argue for an increased emphasis on cooperative learning as a school-wide prevention program that can enhance social, behavioral, and academic outcomes for students.

Highlights.

We tested mediators of effects of cooperative learning (CL) on alcohol use.

CL should increase peer relatedness, reducing deviant peer affiliation.

These effects, in turn, should reduce alcohol use.

We used a cluster randomized trial of 15 middle schools (1,890 students).

Statistical results confirmed our hypotheses.

Acknowledgements

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R34AA024275-01) provided financial support for this project. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukowski WM (2003). Peer relationships In Bornstein MH, Davidson L, Keyes CLM, & Moore KA (Eds.), Crosscurrents in contemporary psychology. Well-being: Positive development across the life course (pp. 221–233). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Criss MM, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA, & Lapp AL (2002). Family adversity, positive peer relationships, and children’s externalizing behavior: A longitudinal perspective on risk and resilience. Child Development, 73, 1220–1237. DOI: 10.1111/1467-8624.00468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Goldstein RB, Chou SP, Ruan WJ, & Grant BF (2008). Age at first drink and the first incidence of adult-onset DSM-IV alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32, 2149–2160. DOI: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00806.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M (1949). A theory of cooperation and competition. Human Relations, 2, 129–151. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch M (1962). Cooperation and trust: Some theoretical notes In Jones M (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (pp. 275–319). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Owen LD (2002). A longitudinal analysis of friendships and substance use: Bidirectional influence from adolescence to adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 38, 480–491. DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.38.4.480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, & Patterson GR (2006). The development and ecology of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents In Cicchetti D & Cohen DJ (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 3. Risk, disorder, and adaptation (pp. 503–541). New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, & Skinner ML (1991). Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology, 27, 172–180. DOI: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.172 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, & Bandalos DL (2001). The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling, 8, 430–457. DOI: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Swain-Campbell NR, & Horwood LJ (2002). Deviant peer affiliations, crime and substance use: A fixed effects regression analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 30, 419–430. DOI: 10.1023/A:1015774125952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furrer C, & Skinner E (2003). Sense of relatedness as a factor in children's academic engagement and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 148–162. DOI: 10.1037/0022-0663.95.1.148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, & Dishion TJ (2003). Deviant talk in adolescent friendships: A step toward measuring a pathogenic attractor process. Social Development, 12, 314–334. DOI: 10.1111/1467-9507.00236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haynie DL, & Osgood DW (2005). Reconsidering peers and delinquency: How do peers matter? Social Forces, 84, 1109–1130. DOI: 10.1353/sof.2006.0018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, & Zha W (2009). Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics, 123, 1477–1484. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. DOI: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson R, & Holubec E (2013). Cooperation in the classroom (9th ed.) Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson RT, & Maruyama G (1983). Interdependence and interpersonal attraction among heterogeneous and homogeneous individuals: A theoretical formulation and a meta-analysis of the research. Review of Educational Research, 53, 5–54. DOI: 10.3102/00346543053001005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson RT, Roseth CJ, & Shin T-S (2014). The relationship between motivation and achievement in interdependent situations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 622–633. DOI: 10.1111/jasp.12280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Judd CM, Kenny DA, & McClelland GH (2001). Estimating and testing mediation and moderation in within-subject designs. Psychological Methods, 6, 115–134. DOI: 10.1037/1082-989X.6.2.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasgaard M, Goossens L, Bramsen RH, Trillingsgaard T, & Elklit A (2011). Different sources of loneliness are associated with different forms of psychopathology in adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 45, 233–237. DOI: 10.1016/j.jrp.2010.12.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liem GAD, & Martin AJ (2011). Peer relationships and adolescents’ academic and non-academic outcomes: Same- sex and opposite- sex peer effects and the mediating role of school engagement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 183–206. DOI: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2010.02013.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol K, Sleegers P, Veenman S, & Voeten M (2008). Creating cooperative classrooms: Effects of a two- year staff development program. Educational Studies, 34, 343–360. DOI: 10.1080/03055690802257101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur GJ, Harrison S, Caldwell DM, Hickman M, & Campbell R (2016). Peer- led interventions to prevent tobacco, alcohol and/or drug use among young people aged 11–21 years: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Addiction, 111, 391–407. DOI: 10.1111/add.13224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, & Dwyer JH (1993). Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144–158. DOI: 10.1177/0193841X9301700202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998-2012). Mplus User's Guide (7th Edition). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, & Ramsey E (1989). A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist, 44, 329–335. DOI: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, & Patra J (2009). Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet, 373(9682), 2223–2233. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseth CJ, Johnson DW, & Johnson RT (2008). Promoting early adolescents' achievement and peer relationships: The effects of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic goal structures. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 223–246. DOI: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, & Morris AS (2001). Adolescent development. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 83–110. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler NS, Roona MR, Ochshorn P, Marshall DG, Streke AV, & Stackpole KM (2000). School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. Journal of Primary Prevention, 20, 275–336. DOI: 10.1023/A:1021314704811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valente TW, Ritt-Olson A, Stacy A, Unger JB, Okamoto J, & Sussman S (2007). Peer acceleration: Effects of a social network tailored substance abuse prevention program among high-risk adolescents. Addiction, 102, 1804–1815. DOI: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01992.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhalst J, Klimstra TA, Luyckx K, Scholte RH, Engels RC, & Goossens L (2012). The interplay of loneliness and depressive symptoms across adolescence: Exploring the role of personality traits. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 776–787. DOI: 10.1007/s10964-011-9726-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2013). From antisocial behavior to violence: A model for the amplifying role of coercive joining in adolescent friendships. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 661–669. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.12017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Dishion TJ (2014). Adolescent deviant peer clustering as an amplifying mechanism underlying the progression from early substance use to late adolescent dependence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55, 1153–1161. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.12211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Fosco GM, & Dishion TJ (2012). Family and peer predictors of substance use from early adolescence to early adulthood: An 11-year prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 37, 1314–1324. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Johnson AB, Leve LD, & Kim HK (2011). The number of sexual partners and health-risking sexual behavior: Prediction from high school entry to high school exit. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 939–949. DOI: 10.1007/s10508-010-9649-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Roseth CJ (2018a). Enlisting peer cooperation in the service of alcohol use prevention in middle school. Child Development, 89, e459–e467. DOI: 10.1111/cdev.12981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Roseth CJ (2018b). Peer influence processes as mediators of effects of a middle school substance use prevention program. Addictive Behaviors, 85, 180–185. DOI: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Roseth CJ (2018c). Cooperative learning in middle school: A means to improve peer relations and reduce victimization, bullying, and related outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110, 1192–1201. DOI: 10.1037/edu0000265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, & Roseth CJ (in press). Effects of cooperative learning on peer relations, empathy, and bullying in middle school. Aggressive Behavior. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veenman S, van Benthum N, Bootsma D, van Dieren J, & van der Kemp N (2002). Cooperative learning and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 87–103. DOI: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00052-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel KR (2005). Peer relationships, motivation, and academic performance at school In Elliot AJ & Dweck CS (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 279–296). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DB, Gottfredson DC, & Najaka SS (2001). School-based prevention of problem behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 17, 247–272. DOI: 10.1023/A:1011050217296 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2014). Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]