Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) infection has been associated with outbreaks of severe respiratory illness and increased cases of nonpolio acute flaccid myelitis. The patterns of EV-D68 circulation and molecular epidemiology are not fully understood. In this study, nasopharyngeal (NP) specimens collected from patients in the Lower Hudson Valley, New York, from 2014 to 2018 were examined for rhinovirus/enterovirus (RhV/EV) by the FilmArray respiratory panel. Selected RhV/EV-positive NP specimens were analyzed using two EV-D68-specific real-time RT-PCR assays, Sanger sequencing and metatranscriptomic next-generation sequencing.

KEYWORDS: enterovirus, enterovirus D68, molecular epidemiology, next-generation sequencing, outbreak investigation, real-time RT-PCR, viral evolution

ABSTRACT

Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) infection has been associated with outbreaks of severe respiratory illness and increased cases of nonpolio acute flaccid myelitis. The patterns of EV-D68 circulation and molecular epidemiology are not fully understood. In this study, nasopharyngeal (NP) specimens collected from patients in the Lower Hudson Valley, New York, from 2014 to 2018 were examined for rhinovirus/enterovirus (RhV/EV) by the FilmArray respiratory panel. Selected RhV/EV-positive NP specimens were analyzed using two EV-D68-specific real-time RT-PCR assays, Sanger sequencing and metatranscriptomic next-generation sequencing. A total of 2,398 NP specimens were examined. EV-D68 was detected in 348 patients with NP specimens collected in 2014 (n = 94), 2015 (n = 0), 2016 (n = 160), 2017 (n = 5), and 2018 (n = 89), demonstrating a biennial upsurge of EV-D68 infection in the study area. Ninety-one complete or nearly complete EV-D68 genome sequences were obtained. Genomic analysis of these EV-D68 strains revealed dynamics and evolution of circulating EV-D68 strains since 2014. The dominant EV-D68 strains causing the 2014 outbreak belonged to subclade B1, with a few belonging to subclade B2. New EV-D68 subclade B3 strains emerged in 2016 and continued in circulation in 2018. Clade D strains that are rarely detected in the United States also arose and spread in 2018. The establishment of distinct viral strains and their variable circulation patterns provide essential information for future surveillance, diagnosis, vaccine development, and prediction of EV-D68-associated disease prevalence and potential outbreaks.

INTRODUCTION

Enteroviruses are small, nonenveloped viruses of the family Picornaviridae with a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome of approximately 7.5 kb. The genus Enterovirus contains seven species that commonly cause human disease, including enteroviruses A to D and rhinoviruses A to C (1). The patterns and outbreak dynamics of individual enterovirus serotypes circulating in different geographic areas are not fully elucidated (2). Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) was first recovered from patients with respiratory illness in California in 1962 (3) and was infrequently recognized until its emergence in the 2000s in Asia, Europe, and a few U.S. states (4–6). In 2014, a nationwide outbreak of severe respiratory illness associated with EV-D68 was noticed in the United States, with at least 1,395 confirmed cases and likely many more infections with mild illness (7). An increase in EV-D68 cases was also documented worldwide in more than 20 countries in 2014 (8, 9).

Since 2014, a biennial circulation of EV-D68 has been noticed in several European countries with various surveillance systems (10–14). In the United States, a passive and laboratory-based surveillance system, the National Enterovirus Surveillance System (NESS), has been used to track EV reports since the 1960s (7). Only 9 EV-D68 cases in 2015 and 138 EV-D68 cases in 2016 have been reported to the NESS (7). Similarly, a low level of EV-D68 circulation was evident in Colorado (15), Arizona (16), Washington (17), and Ohio (18) in 2016, where selective clinical specimens from patients with respiratory and neurological syndromes were investigated for EV-D68. In 2018, increased activity of EV-D68 was reported in Colorado (19), New York (20), and several U.S. states through the recently established CDC New Vaccine Surveillance Network (NVSN) (21).

Given the capacity of EV-D68 to cause outbreaks of severe respiratory illness and its potential association with nonpolio acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), it is essential to elucidate the epidemiology, molecular epidemiology, and viral and clinical characteristics of EV-D68 infection in order to understand its long-term health care burden and impact on public health. Nevertheless, current EV-D68 testing in the U.S. clinical laboratories is limited, and reporting of EV-D68 cases to the CDC is voluntary. Due to the lack of a nationwide active surveillance system, EV-D68 infection and its molecular epidemiology in the United State are still not fully understood. During the 2014 U.S. outbreak, we detected EV-D68 in nasopharyngeal (NP) specimens collected in September and October 2014 from 94 children in the Lower Hudson Valley, New York, using an EV-D68-specific real-time reverse-transcription-PCR (CDC rRT-PCR) (22) and a metatranscriptomic next-generation sequencing assay (mtNGS) (23). Subsequent surveillance revealed another regional EV-D68 outbreak from June to October 2016 with 160 laboratory-confirmed cases (24). Here, we report our 5-year enhanced laboratory-based surveillance and molecular epidemiology data on EV-D68 infection among patients in the same area from 2014 to 2018. We demonstrate a biennial upsurge of EV-D68 infection and circulation of distinct viral clades and subclades of strains in New York, USA, during this study period.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and detection of RhV/EV in NP specimens.

The Lower Hudson Valley, NY, is located immediately north of New York City and consists of seven counties (Westchester, Putnam, Dutchess, Orange, Rockland, Ulster, and Sullivan counties) with approximately three million residents. Westchester Medical Center (WMC) is a tertiary health care facility with a children’s hospital, mainly serving patients in the Lower Hudson Valley. Patients included in this study were those with respiratory illness and/or other medical conditions who visited or were hospitalized in multiple medical facilities in the Lower Hudson Valley from January 2014 through December 2018. The majority of patients were those who visited the emergency department or were hospitalized at the Maria Fareri Children’s Hospital of WMC. NP specimens were collected into tubes, each with 1 ml of viral transport medium (Diagnostic Hybrid, San Diego, CA), and were analyzed for the presence of rhinovirus/enterovirus (RhV/EV) and other respiratory pathogens using the FilmArray respiratory panel (RP) kit on the FilmArray instrument (BioFire, Salt Lake City, UT). The New York Medical College Institutional Review Board approved all experimental protocols of this study and granted a waiver of informed consent from study subjects.

Detection of EV-D68 in NP specimens by rRT-PCR.

From 2014 to 2018, 4,949 of 21,648 (22.9%) NP specimens analyzed by the RP assay were positive for RhV/EV. Of these, 2,548 NP specimens were selected by the following criteria and further analyzed using EV-D68-specific rRT-PCR assays: (i) all leftover RhV/EV-positive NP specimens collected between September to October in 2014 (n = 319) and 2015 (n = 199); (ii) consecutive RhV/EV-positive NP specimens from 2016 (n = 654), 2017 (n = 695), and 2018 (n = 583) (Table 1) that included all specimens from July to October, and randomly selected RhV/EV-positive NP specimens, representing approximately 25% of positive RhV/EV or at least 20 NP specimens per month, from other months; and (iii) randomly selected representative RhV/EV-negative NP specimens between 2014 to 2018. For patients with multiple NP specimens examined during the study period, only the first NP specimen positive for RhV/EV was included in the final analysis for EV-D68.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of nasopharyngeal specimens examined for EV-D68, 2014 to 2018a

| Yr | No. of NPS tested | No. of NPS positive for RhV/EV (%) | No. of NPS tested for EV-D68 (%) | No. of NPS positive for EV-D68 (%) | No. of assembled genomes | EV-D68 clade (no. of strains) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 3,762 | 917 (24.4) | 319 (34.8) | 94 (29.5) | 20 | Subclade B1 (18), B2 (2) |

| 2015 | 4,310 | 1,034 (24.0) | 199 (19.2) | 0 | 0 | |

| 2016 | 4,666 | 1,041 (22.3) | 654 (62.8) | 160 (24.5) | 22 | Subclade B3 (22) |

| 2017 | 4,298 | 889 (20.7) | 695 (78.2) | 5 (0.7) | 1 | Clade D (1) |

| 2018 | 4,612 | 1,068 (23.2) | 681 (63.8) | 89 (13.1) | 48 | Subclade B3 (37), Clade D (11) |

| Total | 21,648 | 4,949 (22.9) | 2,548 (51.5) | 348 (13.7) | 91 |

Data for 2014 and 2015 were adapted from reference 24. NPS, nasopharyngeal specimens.

A previously validated EV-D68 rRT-PCR (CDC rRT-PCR) was employed to analyze NP specimens from 2014 to 2016 (22). For enhanced surveillance of EV-D68 in 2017 and 2018, we developed a new EV-D68-specific rRT-PCR (WMC rRT-PCR) targeting the VP1 region with improved sensitivity compared to that of the CDC rRT-PCR. For both rRT-PCR assays, total RNA was extracted from NP specimens (∼150 μl) using the EZ1 virus minikit v2.0 (for NP specimens collected in 2014 and 2016; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) on the EZ1 Advanced XL instrument (Qiagen) or using the NucliSENS EasyMAG system (for NP specimens collected from 2017 to 2018; bioMérieux, Durham, NC) without carrier RNA. RNA was eluted in 60 μl of buffer. A single-step rRT-PCR was carried out on either an ABI 7500 Fast Dx or ViiA7 real-time PCR system (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For the WMC rRT-PCR, the rRT-PCR tube with a total volume of 25 μl consisted of 1× reaction buffer, SuperScript III RT/Platinum Taq mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), 0.32 μM each primer, DF (5′-CAGGACTCATTCCACTGGCA-3′) and DR (5′-AAAAGGTATGGTTATTCTGGCTGG-3′), 0.16 μM probe DP (5′-FAM [6-carboxyfluorescein]-AGTAATGCTAGTGTATTCTT-MGB-3′), 4 mM Mg2+, and 5 μl of RNA elution in the final reaction. The reverse transcription was performed at 50°C for 30 min, followed by 2 min at 95°C for polymerase activation and 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 65°C for 45 s. A positive control and a nontemplate negative control were included in each run as previously described (22).

mtNGS.

For NP specimens from 2014 and 2015, selected RhV/EV-positive and negative NP specimens were analyzed by metatranscriptomic next-generation sequencing (mtNGS) on the MiSeq or NextSeq 550 system (Illumina, San Diego, CA) as described previously (23, 25). A modified mtNGS protocol was employed to analyze NP specimens from 2016 to 2018 (26). Raw sequence reads were aligned and curated using reference genomes (strain NY120_14 [GenBank accession number KP745751] and strain NY230_16 [KY385890]) as described previously (24).

Phylogenetic analysis.

A total of 91 complete or nearly complete genomes of EV-D68 strains obtained by mtNGS in this study and representing reference genomes from GenBank were included in comparative genome analysis. Sequences were aligned, and a phylogenetic tree based on whole-genome sequences was constructed using the unweighted pair-group method with arithmetic averages (UPGMA) clustering method with BioNumerics software (v7.6; Applied Maths, Belgium).

Statistical analysis.

GraphPad Prism software (v7; GraphPad, La Jolla, CA) was used for statistical analysis, including the chi-square test and analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Accession number(s).

Ninety-one complete or nearly complete genomes of EV-D68 strains from the Lower Hudson Valley have been deposited in the NCBI GenBank database with accession numbers KP745751 to KP745770 for 2014 (n = 20), KX957754 to KX957762 and KY385880 to KY385892 for 2016 (n = 22), MG757146 for 2017 (n = 1), and MK419033 to MK419080 for 2018 (n = 48).

RESULTS

Detection of RhV/EV in the Lower Hudson Valley, 2014 to 2018.

From January 2014 to December 2018, a total of 21,648 NP specimens were analyzed by the FilmArray RP assay. Overall, 22.9% of these NP specimens were positive for RhV/EV (Table 1). The yearly RhV/EV positivity rates were comparable during the period from 2014 to 2018 (P > 0.05).

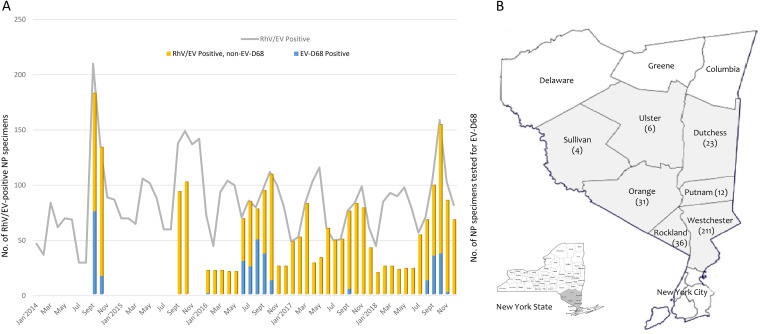

The monthly distribution of RhV/EV-positive NP specimens from 2014 to 2018 analyzed by the FilmArray RP assay is shown in Fig. 1. A minor peak of RhV/EV positives in the spring and early summer and a major peak during autumn and early winter were observed in most of the years. The major peak observed in September and October 2014 corresponded to the U.S. nationwide EV-D68 outbreak.

FIG 1.

Temporal and geographic distributions of enterovirus D68 in the Lower Hudson Valley, NY, 2014 to 2018. (A) Monthly distribution of nasopharyngeal (NP) specimens that were positive for rhinovirus/enterovirus (RhV/EV) (left y axis) and EV-D68 (right y axis) from January 2014 to December 2018. (B) Map of the seven counties in the Lower Hudson Valley and distribution of the number of patients with enterovirus D68 detected from respiratory specimens between 2014 and 2018. Three hundred twenty-three of 348 (92.8%) confirmed cases were from this region. The map was adapted from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation website (http://www.dec.ny.gov/outdoor/7804.html) with permission.

Detection of EV-D68 by rRT-PCR, 2014 to 2018.

NP specimens collected in 2014 to 2016 were analyzed using the CDC rRT-PCR (22). EV-D68 was detected in 94 of 319 (29.5%) NP specimens in 2014 and 160 of 654 (24.5%) NP specimens in 2016. Of 199 NP specimens collected in September and October 2015, none were positive for EV-D68 by the CDC rRT-PCR.

Starting January 2017, the WMC rRT-PCR was employed. The limit of detection (LOD) of the WMC rRT-PCR was 8 copies per reaction, with a 95% confidence interval of 5 to 35 copies, as determined by probit regression analysis using serially diluted genomic RNA from EV-D68 strain US/KY/1418953 (ATCC VR1825D) (27). The WMC rRT-PCR was comparable in LOD and performance to the rRT-PCR protocol described by Wylie et al. but was more sensitive than the CDC rRT-PCR (27, 28). Six-hundred ninety-five of 889 (78.2%) RhV/EV-positive NP specimens in 2017 and 681 of 1,068 (63.8%) RhV/EV-positive NP specimens in 2018 were analyzed by the WMC rRT-PCR. Five (0.7%) and 89 (13.1%) NP specimens in 2017 and 2018 were positive for EV-D68, with median cycle thresholds (CT) of 34.4 and 26.0, respectively. Interestingly, all five positive specimens in 2017 were confirmed by mtNGS, including the assembly of a clade D complete genome sequence from one specimen. Four of these five specimens were also positive by a reference rRT-PCR (28), but none were positive by the CDC rRT-PCR.

Overall, EV-D68 was detected in 348 patients by analyzing 2,548 NP specimens collected from 2014 to 2018. EV-D68 was mainly detected in patients in 2014 (n = 94), 2016 (n = 160), and 2018 (n = 89), with no cases in 2015 and only 5 cases in 2017, showing a biennial upsurge in the Lower Hudson Valley. The temporal and geographic distributions of laboratory-confirmed EV-D68 cases from 2014 to 2018 are shown in Fig. 1.

Clinical characteristics of EV-D68 infection, 2014 to 2018.

Since the majority of cases (343 of 348 [98.6%]) were from a biennial upsurge in 2014, 2016, and 2018, we compared and summarized the clinical characteristics of cases in these 3 years (Table 2). There were no significant differences in patients who were hospitalized and in pediatric patients who were admitted to the intensive care units across these 3 years. While all 94 cases in 2014 were in pediatric patients, 15 (9%) and 12 (13%) cases were in adult patients in 2016 and 2018, respectively (P = 0.0034). The median ages of all cases in 2016 and 2018 were 2.4 and 2.6 years, respectively, which were significantly lower than those of patients in 2014, 4.8 years old (P = 0.0041).

TABLE 2.

Comparative clinical and laboratory characteristics of EV-D68 infection, 2014 to 2018a

| Characteristic | Value for indicated yr |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | ||

| No. of patients | 94 | 160 | 89 | |

| No. of patient hospitalized (%) | 64 (68) | 121 (76) | 69 (78) | 0.2854 |

| No. of pediatric patients (%) | 94 (100) | 145 (91) | 78 (88) | 0.0034 |

| Median age (yrs) | 4.8 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0.0041 |

| Male (%) | 64 (67.6) | 91 (62.1) | 43 (48.3) | 0.0246 |

| Clinical presentation of pediatric patients | ||||

| No. of patients with clinical data | 72b | 104 | 72 | |

| No. of patients admitted to ICU (%) | 21 (29) | 31 (30) | 22 (36) | 0.8560 |

| Fever | 44 (61) | 73 (70) | 46 (64) | 0.4254 |

| Cough | NA | 75 (72) | 39 (54) | 0.0143 |

| Shortness of breath | 49 (68) | 61 (59) | 40 (56) | 0.2719 |

| Wheezing | 56 (78) | 53 (51) | 38 (53) | 0.0007 |

| Exacerbation of asthma | 49 (68) | 37 (36) | 29 (40) | <0.0001 |

| No. of patients with AFM | 0 | 2 | 2c | |

| EV-D68 clade(s) detected | B1, B2 | B3 | B3, D | |

| Median CT (rRT-PCR) | 26.8 | 28.9 | 26.0 | |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; NA, not applicable; AFM, acute flaccid myelitis.

Adapted from reference 29.

Two probable pediatric cases, one with ascending muscle weakness and one with left upper extremity weakness.

Clinical data were available from 72, 104, and 72 pediatric patients in 2014 (29), 2016, and 2018, respectively. The overall clinical presentations, including intensive care unit admission and symptoms like fever, cough, and shortness of breath, were similar across these 3 years, except that more patients had wheezing and asthma exacerbation in 2014. We had two confirmed and two probable cases of acute flaccid myelitis in 2016 and 2018, respectively; both confirmed cases in 2016 were positive for EV-D68 in NP specimens.

Phylogenetic analysis of EV-D68 strains, 2014 to 2018.

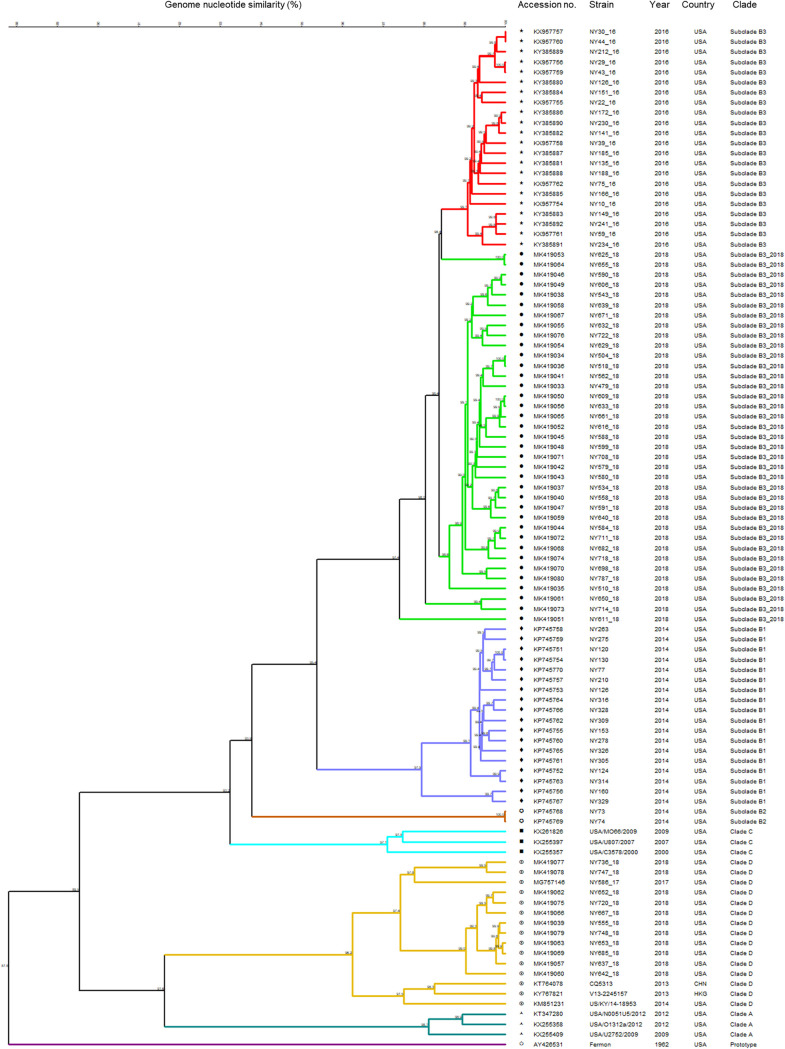

Ninety-one complete or nearly complete EV-D68 genomes were obtained from NP specimens of patients from 2014 to 2018. Comparative whole-genome analysis of our local EV-D68 strains along with representing reference genomes from GenBank revealed that distinct viral strains were circulating in the Lower Hudson Valley from 2014 to 2018 (Fig. 2). The majority of EV-D68 strains in 2014 (18 of 20 [90%]) belonged to the novel subclade B1, with only two strains belonging to subclade B2. In contrast, all 22 EV-D68 strains in 2016 were determined to be subclade B3. In 2017, one complete genome was obtained from an adult patient; the strain NY586_17 belonged to EV-D68 clade D, with 96.0% to 96.6% identity in nucleotides to clade D strains US/KY/14-18953 (GenBank accession no. KM851231, USA, 2014) and CQ5313 (GenBank accession no. KT764078, China, 2013), which was genetically distant from subclade B1 (89.1%), B2 (89.2%), and B3 (88.8%) strains circulating in the Lower Hudson Valley in 2014 and 2016. A total of 48 complete or nearly complete genomes were assembled from mtNGS of NP specimens during the 2018 upsurge of EV-D68. Of these, 37 (77.1%) strains were classified as subclade B3, but the majority of these 2018 subclade B3 strains clustered into a separate subgroup, differing from the B3 strains in 2016.

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic tree of enterovirus D68 strains from the Lower Hudson Valley from 2014 to 2018 (n = 91). Strains representing each clade (A, C, D, and prototype) were included for comparison. The numbers at the branch nodes are percent nucleotide sequence identity. CHN, China; HKG, Hong Kong, China.

Further comparisons on the nucleic acid similarity of different EV-D68 strains in the Lower Hudson Valley from 2014 to 2018 are summarized in Table 3. The 2018 subclade B3 strains showed 98.3% to 98.7% identity to the 2016 subclade B3 strains in nucleic acid sequences, or 95 to 130 nucleic acid substitutions in an average genome of 7.5 kb. The EV-D68 clade D strains (n = 11) from 2017 and 2018 showed 97.2% to 99.5% identity each other in nucleotides. The approximate genomic divergence was 8% to 9% between clade D and clade A or clade C but 10% to 12% between clade D and subclade B1 or B3 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Identity of whole-genome nucleotides among representative EV-D68 strains from the Lower Hudson Valley, NY, 2014 to 2018a

| EV-D68 strainb | Yr | Clade | % identity |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B3-2016 |

B3-2018 |

B1-2014 |

B2-2014 |

Clade C |

Clade D-2017/2018 |

Clade A |

Prototype fermon | |||||||||||||||||

| NY212_16 | NY230_16 | NY234_16 | NY606_18 | NY543_18 | NY639_18 | NY120 | NY130 | NY329 | NY73 | NY74 | USA/U807 | USA/MO66 | USA/C3578 | NY736_18 | NY747_18 | NY586_17 | NY652_18 | USA/N0051U5 | USA/O1312a | USA/U2752 | ||||

| NY212_16 | 2016 | Subclade B3 | 100 | 99.4 | 99.2 | 98.7 | 98.6 | 98.6 | 95.7 | 95.8 | 95.8 | 94.0 | 94.2 | 93.1 | 92.4 | 94.7 | 89.4 | 89.1 | 89.1 | 89.7 | 90.1 | 90.2 | 90.7 | 88.0 |

| NY230_16 | 2016 | Subclade B3 | 100 | 99.2 | 98.7 | 98.6 | 98.5 | 95.7 | 95.8 | 95.7 | 93.9 | 94.2 | 93.0 | 92.4 | 94.5 | 89.4 | 89.1 | 89.1 | 89.7 | 90.0 | 90.1 | 90.7 | 87.9 | |

| NY234_16 | 2016 | Subclade B3 | 100 | 98.5 | 98.4 | 98.3 | 95.7 | 95.8 | 95.7 | 94.0 | 94.2 | 93.1 | 92.4 | 94.7 | 89.5 | 89.2 | 89.2 | 89.8 | 90.0 | 90.1 | 90.6 | 87.9 | ||

| NY606_18 | 2018 | Subclade B3 | 100 | 99.6 | 99.6 | 95.3 | 95.4 | 95.4 | 93.1 | 93.3 | 92.7 | 92.1 | 94.3 | 89.0 | 88.7 | 88.7 | 89.4 | 89.7 | 89.7 | 90.3 | 87.7 | |||

| NY543_18 | 2018 | Subclade B3 | 100 | 99.6 | 95.3 | 95.4 | 95.4 | 93.0 | 93.3 | 92.7 | 92.1 | 94.3 | 89.1 | 88.9 | 88.8 | 89.4 | 89.7 | 89.8 | 90.3 | 87.8 | ||||

| NY639_18 | 2018 | Subclade B3 | 100 | 95.3 | 95.3 | 95.3 | 93.1 | 93.3 | 92.7 | 92.1 | 94.2 | 89.1 | 88.8 | 88.7 | 89.4 | 89.6 | 89.8 | 90.3 | 87.7 | |||||

| NY120 | 2014 | Subclade B1 | 100 | 100 | 97.9 | 94.3 | 94.6 | 93.2 | 92.8 | 94.9 | 89.6 | 89.3 | 89.2 | 89.6 | 90.2 | 90.2 | 90.7 | 87.7 | ||||||

| NY130 | 2014 | Subclade B1 | 100 | 98.0 | 94.4 | 94.6 | 93.2 | 92.9 | 95.0 | 89.6 | 89.4 | 89.3 | 89.7 | 90.2 | 90.2 | 90.8 | 87.8 | |||||||

| NY329 | 2014 | Subclade B1 | 100 | 94.2 | 94.5 | 93.3 | 93.1 | 95.0 | 90.0 | 89.8 | 89.6 | 90.0 | 90.6 | 90.5 | 91.1 | 88.0 | ||||||||

| NY73 | 2014 | Subclade B2 | 100 | 100 | 93.1 | 92.2 | 94.5 | 88.9 | 88.9 | 88.8 | 89.3 | 90.0 | 90.2 | 90.6 | 87.6 | |||||||||

| NY74 | 2014 | Subclade B2 | 100 | 93.3 | 92.4 | 94.7 | 89.1 | 89.1 | 89.0 | 89.3 | 90.1 | 90.3 | 90.7 | 87.8 | ||||||||||

| USA/U807 | 2007 | Clade C | 100 | 97.5 | 97.5 | 90.4 | 90.4 | 90.5 | 90.6 | 91.6 | 91.5 | 92.3 | 88.5 | |||||||||||

| USA/MO66 | 2009 | Clade C | 100 | 96.7 | 89.9 | 89.9 | 90.1 | 90.1 | 91.2 | 91.1 | 91.7 | 88.4 | ||||||||||||

| USA/C3578 | 2000 | Clade C | 100 | 91.6 | 91.6 | 91.6 | 91.8 | 92.7 | 92.6 | 93.4 | 89.4 | |||||||||||||

| NY736_18 | 2018 | Clade D | 100 | 99.5 | 97.6 | 97.4 | 90.8 | 91.0 | 91.4 | 87.2 | ||||||||||||||

| NY747_18 | 2018 | Clade D | 100 | 98.0 | 97.2 | 91.0 | 91.2 | 91.6 | 87.4 | |||||||||||||||

| NY586_17 | 2017 | Clade D | 100 | 97.4 | 91.2 | 91.3 | 91.6 | 87.5 | ||||||||||||||||

| NY652_18 | 2018 | Clade D | 100 | 91.2 | 91.3 | 91.8 | 87.8 | |||||||||||||||||

| USA/N0051U5 | 2012 | Clade A | 100 | 98.9 | 98.1 | 88.1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| USA/O1312a | 2012 | Clade A | 100 | 98.1 | 88.2 | |||||||||||||||||||

| USA/U2752 | 2009 | Clade A | 100 | 88.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Fermon | 1962 | Prototype | 100 | |||||||||||||||||||||

Data in gray boxes are the nucleotide identities of representative EV-D68 strains from the specific year and viral clade/subclade.

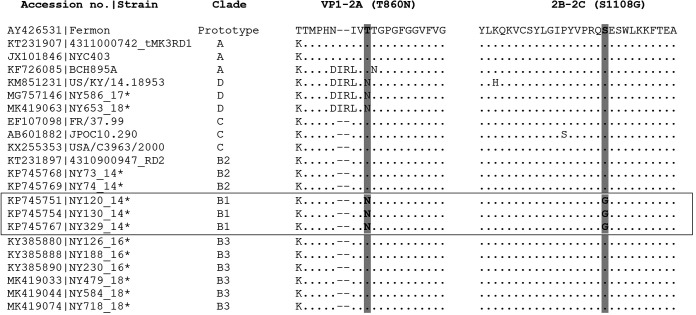

Amino acid substitutions at VP1, protease 2Apro, and 3Cpro cleavage sites.

We previously identified 28 amino acid polymorphisms between subclade B3 strains from 2016 and subclade B1 strains from 2014 on the basis of the complete polypeptide sequences of approximately 2,190 amino acids (24). The average amino acid identity between subclade B3 strains from 2016 (n = 22) versus 2018 (n = 37) was 99.7% (range, 99.4% to 99.8%). No consensus amino acid substitutions were observed between the 2016 and 2018 subclade B3 strains, with the exception of T650A, T653A, and N695S, which were seen in 32 (86.5%), 32 (86.5%), and 34 (91.9%) of 37 subclade B3 strains from 2018, respectively. Interestingly, all these three amino acid variations occurred in the BC (T650A and T653A) and DE (N695S) loops of the VP1 protein. Also, as shown in Fig. 3, the two amino acid variables (T860N and S1108G) at the protease 2Apro and 3Cpro cleavage sites identified in all 2014 subclade B1 strains were not observed in any subclade B3 strains from 2016 and 2018, while the T860N substitution alone at the protease 2Apro cleavage site was noticed in clade D strains from 2014, 2017, and 2018.

FIG 3.

Alignment of amino acid sequences at the cleavage sites of proteases 2Apro and 3Cpro of 27 representative EV-D68 strains. Two amino acid substitutions, T860N in 2Apro at the position between VP1 and 2A and S1108G in 3Cpro between 2B and 2C, were observed only in the subclade B1 strains from the 2014 outbreak. The gaps are indicated by dashes and the conserved amino acid residues by dots. Asterisks indicate EV-D68 strains from the Lower Hudson Valley.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we reported detection of EV-68 and molecular epidemiology of circulating EV-D68 strains in the Lower Hudson Valley, NY, from 2014 to 2018. Upsurge of EV-D68 was only recognized in 2014, 2016, and 2018 with 94, 160, and 89 laboratory-confirmed cases, respectively. No EV-D68 case was detected in 2015, and only 5 cases were identified in 2017, supporting a biennial upsurge of EV-D68 in this particular geographic area.

Comparison between our and published data suggests considerable geographic and temporal variation in EV-D68 infection. First, studies in the United States noticed a widespread of EV-D68 cases in 2014 and 2018 but only low-level EV-D68 circulation in 2016 in some states, such as Colorado (15), Missouri (30), and Ohio (18). In contrast, we had a high percentage (24.5%) of patients with RhV/EV-positive NP specimens typed as EV-D68 in the Lower Hudson Valley, as well as the largest number of cases from a single health care facility in the United States in 2016. Recently, Uprety et al. also reported high prevalence of EV-D68 and the most AFM cases in 2016 among pediatric patients from Philadelphia, PA (31). These observations highlight some regional or local pockets of transmission over broader geographic areas in EV-D68 endemic or outbreak circumstances, as well as regional variation in EV-D68 prevalence between some northeast and central U.S. states in 2016. Second, we recognized a substantial seasonal variation in the monthly distribution of cases in each of the 3 years with an EV-D68 upsurge. While seasonal peaks were observed in September and October in 2014 and 2018, the upsurge of EV-D68 in 2016 started in June and spanned over 5 months from June to October 2016. Also, more than one-third (57 of 160, 35.6%) of our cases in 2016 were from patient specimens collected in June and July. Frequently, such specimens may not be selected and subsequently examined for EV-D68 (15, 21, 31, 32). It is unclear whether such a selection bias contributed to dissociation in the number of EV-68 and AFM cases reported in the US in 2016 (7, 33).

Ninety-one complete or nearly complete EV-D68 genome sequences were achieved from our patients in the Lower Hudson Valley from 2014 to 2018. These represent the largest EV-D68 strains with complete genomes from a single U.S. institution. Genomic analysis of these EV-D68 strains revealed a striking evolution of distinct viral strains in circulation in this geographic area.

The dominant EV-D68 strains causing the 2014 outbreak belonged to subclade B1 with a few cocirculating subclade B2 strains (25, 34–37). This differed from those in most European countries, where subclade B2 strains was dominant and mixed with some B1 and clade A strains (9). All EV-D68 strains identified in 2016 were subclade B3 (n = 22), with high genetic similarity to the B3 previously reported in Asia around 2014 (38) and in multiple European countries around 2016 (13, 14). In 2018, 37 (77.1%) of 48 EV-D68 strains were subclade B3 and the remaining 11 belonged to clade D. The 2018 subclade B3 strains were >98.3% identical to the 2016 subclade B3 strains, with difference in ∼95 to 130 nucleotides, which was within a range on the projected number of nucleotide substitutions in the EV-D68 genome over a 2-year period (4, 24). The majority of the 2018 subclade B3 strains clustered into a separate but closely related subgroup from the B3 strains in 2016. Thus, they are more likely derived from the 2016 subclade B3.

Clade D strains are rarely detected in the United States (only 2 of 1,047 EV-D68 sequences in GenBank, accession no. KM851231 and MF159625, accessed 31 January 2018). The epidemiology and viral and clinical characteristics of EV-D68 clade D infection remain unknown. In 2017, we noticed for the first time laboratory-confirmed cases of EV-D68 clade D infection in our region (27). Subsequently, 11 of 48 (22.9%) EV-D68 strains with complete genome sequences were confirmed as clade D in 2018. This is probably the largest case series with clade D viral infection reported in the United States to date. Notably, the T860N substitutions at the protease 2Apro cleavage site are well conserved in all clade D strains examined. The rapid emergence of clade D strains in our region, as well as the wide spread of this clade in Eurasia since 2016 (39–41), raises concern on its potential in causing next EV-D68 outbreak in the United States. Nevertheless, current surveillance systems are challenging in monitoring the potential emergence of new viral strains (7, 28, 42). As demonstrated in our study, all five EV-D68-positive specimens in 2017 were detectable only by an EV-D68 rRT-PCR assay with improved sensitivity, signifying the necessity of EV-D68 surveillance by using molecular assays that are capable of detecting low-level viruses present in some specimens.

We previously identified 28 amino acid polymorphisms between subclade B3 strains from 2016 and B1 from 2014 in the United States on basis of the complete polypeptide sequences of approximately 2,190 amino acids (24). The average amino acid identity between subclade B3 strains from 2016 (n = 22) versus 2018 (n = 37) was 99.7% (range, 99.4% to 99.8%). Only three amino acid substitutions (T650A, T653A, and N695S) were observed in 86.5% to 91.9% of 2018 subclade B3 strains. It is notable that all three amino acid variations occurred in the BC (T650A and T653A) and DE (N695S) loops of the VP1 protein. Also, the two amino acid variables (T860N and S1108G at the protease 2Apro and 3Cpro cleavage sites, respectively) observed in all 2014 subclade B1 strains, which may have contributed to the 2014 EV-D68 nationwide outbreak with increased efficacy in viral replication and transmission (25), were not detected in any 2016 or 2018 subclade B3 strains. It is unknown whether the reduced incidences of disease in 2016 and 2018 in the United States are the result of the lack of these two mutations in subclade B3 strains, altered population immunity, or other unidentified factors.

Our study has certain limitations. Our data were only derived from patients who visited or were hospitalized in three hospitals (Westchester Medical Center, Maria Fareri Children’s Hospital, and Mid-Hudson Regional Hospital) of the Lower Hudson Valley, which might not reflect the incidence of EV-D68 infection and diseases in the region. Also, an unequal sampling of RhV/EV-positive specimens was evaluated for EV-D68 in each year (Table 1). Nevertheless, since approximately 50% of RhV/EV-positive specimens, including all RhV/EV-positive specimens from the anticipated peak months each year, were examined for EV-D68, the results most likely represented the nature of biennial upsurge of EV-D68 among the population in the specific study period.

In summary, we examined EV-D68 in 2,548 (51.5%) of RhV/EV-positive NP specimens from five consecutive years since 2014. Our study confirmed a biennial upsurge of EV-D68 with dynamics in viral strains and variable levels of circulation in the Lower Hudson Valley, New York, which provides essential information for future surveillance, diagnosis, vaccine development, and control of EV-D68 infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was in part supported by the Department of Pathology of New York Medical College.

No authors report a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.ICTV. 2015. Virus taxonomy, 2015 release. http://www.ictvonline.org/virustaxonomy.asp.

- 2.Pons-Salort M, Oberste MS, Pallansch MA, Abedi GR, Takahashi S, Grenfell BT, Grassly NC. 2018. The seasonality of nonpolio enteroviruses in the United States: patterns and drivers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:3078–3083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721159115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schieble JH, Fox VL, Lennette EH. 1967. A probable new human picornavirus associated with respiratory diseases. Am J Epidemiol 85:297–310. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tokarz R, Firth C, Madhi SA, Howie SR, Wu W, Sall AA, Haq S, Briese T, Lipkin WI. 2012. Worldwide emergence of multiple clades of enterovirus 68. J Gen Virol 93:1952–1958. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.043935-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. 2011. Clusters of acute respiratory illness associated with human enterovirus 68—Asia, Europe, and United States, 2008–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60:1301–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imamura T, Oshitani H. 2015. Global reemergence of enterovirus D68 as an important pathogen for acute respiratory infections. Rev Med Virol 25:102–114. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abedi GR, Watson JT, Nix WA, Oberste MS, Gerber SI. 2018. Enterovirus and parechovirus surveillance—United States, 2014–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67:515–518. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6718a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holm-Hansen CC, Midgley SE, Fischer TK. 2016. Global emergence of enterovirus D68: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis 16:e64–e75. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(15)00543-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poelman R, ESCV-ECDC EV-D68 study group, Schuffenecker I, Van Leer-Buter C, Josset L, Niesters HG, Lina B. 2015. European surveillance for enterovirus D68 during the emerging North-American outbreak in 2014. J Clin Virol 71:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.07.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kramer R, Sabatier M, Wirth T, Pichon M, Lina B, Schuffenecker I, Josset L, Chen IJ, Hu SC, Hung KL, Lo CW. 2018. Molecular diversity and biennial circulation of enterovirus D68: a systematic screening study in Lyon, France, 2010 to 2016. Euro Surveill 23:1700711. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.23.37.1700711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 8 August 2016. Rapid risk assessment. Enterovirus detections associated with severe neurological symptoms in children and adults in European countries, p 1–9. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Solna, Sweden. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cottrell S, Moore C, Perry M, Hilvers E, Williams C, Shankar AG. 2018. Prospective enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) surveillance from September 2015 to November 2018 indicates a current wave of activity in Wales. Euro Surveill 23:1800578. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyrdak R, Grabbe M, Hammas B, Ekwall J, Hansson KE, Luthander J, Naucler P, Reinius H, Rotzen-Ostlund M, Albert J. 2016. Outbreak of enterovirus D68 of the new B3 lineage in Stockholm, Sweden, August to September 2016. Euro Surveill 21:30403. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knoester M, Scholvinck EH, Poelman R, Smit S, Vermont CL, Niesters HG, Van Leer-Buter CC. 2017. Upsurge of enterovirus D68, the Netherlands, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 23:140–143. doi: 10.3201/eid2301.161313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messacar K, Robinson CC, Pretty K, Yuan J, Dominguez SR. 2017. Surveillance for enterovirus D68 in Colorado children reveals continued circulation. J Clin Virol 92:39–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iverson SA, AFM Investigation Team, Ostdiek S, Prasai S, Engelthaler DM, Kretschmer M, Fowle N, Tokhie HK, Routh J, Sejvar J, Ayers T, Bowers J, Brady S, Rogers S, Nix WA, Komatsu K, Sunenshine R, Team A. 2017. Notes from the field: cluster of acute flaccid myelitis in five pediatric patients—Maricopa County, Arizona, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:758–760. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6628a4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonwitt J, Poel A, DeBolt C, Gonzales E, Lopez A, Routh J, Rietberg K, Linton N, Reggin J, Sejvar J, Lindquist S, Otten C. 2017. Acute flaccid myelitis among children—Washington, September–November 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 66:826–829. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6631a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Diaz A, Moyer K, Mele-Casas M, Ara-Montojo MF, Torrus I, McCoy K, Mejias A, Leber AL. 2019. Molecular and clinical comparison of enterovirus D68 outbreaks among hospitalized children, Ohio, USA, 2014 and 2018. Emerg Infect Dis 25:2055–2063. doi: 10.3201/eid2511.190973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messacar K, Pretty K, Reno S, Dominguez SR. 2019. Continued biennial circulation of enterovirus D68 in Colorado. J Clin Virol 113:24–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.New York State Department of Health. 12 October 2018. Health advisory: enterovirus D68. New York State Department of Health, Albany, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kujawski SA, Midgley CM, Rha B, Lively JY, Nix WA, Curns AT, Payne DC, Englund JA, Boom JA, Williams JV, Weinberg GA, Staat MA, Selvarangan R, Halasa NB, Klein EJ, Sahni LC, Michaels MG, Shelley L, McNeal M, Harrison CJ, Stewart LS, Lopez AS, Routh JA, Patel M, Oberste MS, Watson JT, Gerber SI. 2019. Enterovirus D68-associated acute respiratory illness—New Vaccine Surveillance Network, United States, July–October, 2017 and 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:277–280. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6812a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhuge J, Vail E, Bush JL, Singelakis L, Huang W, Nolan SM, Haas JP, Engel H, Della Posta M, Yoon EC, Fallon JT, Wang G. 2015. Evaluation of a real-time reverse transcription-PCR assay for detection of enterovirus D68 in clinical samples from an outbreak in New York State in 2014. J Clin Microbiol 53:1915–1920. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00358-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang W, Wang G, Lin H, Zhuge J, Nolan SM, Vail E, Dimitrova N, Fallon JT. 2016. Assessing next-generation sequencing and 4 bioinformatics tools for detection of enterovirus D68 and other respiratory viruses in clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 85:26–29. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G, Zhuge J, Huang W, Nolan SM, Gilrane VL, Yin C, Dimitrova N, Fallon JT. 2017. Enterovirus D68 subclade B3 strain circulating and causing an outbreak in the United States in 2016. Sci Rep 7:1242. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01349-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang W, Wang G, Zhuge J, Nolan SM, Dimitrova N, Fallon JT. 2015. Whole-genome sequence analysis reveals the Enterovirus D68 isolates during the United States 2014 outbreak mainly belong to a novel clade. Sci Rep 5:15223. doi: 10.1038/srep15223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang W, Yin C, Wang G, Rosenblum J, Krishnan S, Dimitrova N, Fallon JT. 2019. Optimizing a metatranscriptomic next-generation sequencing protocol for bronchoalveolar lavage diagnostics. J Mol Diagn 21:251–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilrane VL, Zhuge J, Huang W, Budhai A, Nolan SM, Fallon JT, Wang G. 2018. Enterovirus D68: distinct strains circulating in the United States, 2014–2017. CPHM10—diagnostic virology: the global view of virology. ASM Microbe 2018, 10 June 2018, Atlanta, GA. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wylie TN, Wylie KM, Buller RS, Cannella M, Storch GA. 2015. Development and evaluation of an enterovirus D68 real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay. J Clin Microbiol 53:2641–2647. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00923-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caylan E, Weinblatt E, Welter J, Dozor A, Wang G, Nolan SM. 2018. Comparison of the severity of respiratory disease in children testing positive for enterovirus D68 and human rhinovirus. J Pediatr 197:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Srinivasan M, Niesen A, Storch GA. 2018. Enterovirus D68 surveillance, St. Louis, Missouri, USA, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 24:2115–2117. doi: 10.3201/eid2411.180397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uprety P, Curtis D, Elkan M, Fink J, Rajagopalan R, Zhao C, Bittinger K, Mitchell S, Ulloa ER, Hopkins S, Graf EH. 2019. Association of enterovirus D68 with acute flaccid myelitis, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, 2009–2018. Emerg Infect Dis 25:1676–1682. doi: 10.3201/eid2509.190468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pakala SB, Tan Y, Hassan F, Mai A, Markowitz RH, Shilts MH, Rajagopala SV, Selvarangan R, Das SR. 2019. Nearly complete genome sequences of 17 enterovirus D68 strains from Kansas City, Missouri, 2018. Microbiol Resour Announc 8:e00388-19. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00388-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez A, Lee A, Guo A, Konopka-Anstadt JL, Nisler A, Rogers SL, Emery B, Nix WA, Oberste S, Routh J, Patel M. 2019. Vital Signs: surveillance for acute flaccid myelitis—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 68:608–614. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6827e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brown BA, Nix WA, Sheth M, Frace M, Oberste MS. 2014. Seven strains of enterovirus D68 detected in the United States during the 2014 severe respiratory disease outbreak. Genome Announc 2:e01201-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01201-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greninger AL, Naccache SN, Messacar K, Clayton A, Yu G, Somasekar S, Federman S, Stryke D, Anderson C, Yagi S, Messenger S, Wadford D, Xia D, Watt JP, Van Haren K, Dominguez SR, Glaser C, Aldrovandi G, Chiu CY. 2015. A novel outbreak enterovirus D68 strain associated with acute flaccid myelitis cases in the USA (2012–14): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 15:671–682. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70093-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wylie KM, Wylie TN, Orvedahl A, Buller RS, Herter BN, Magrini V, Wilson RK, Storch GA. 2015. Genome sequence of enterovirus D68 from St. Louis, Missouri, USA. Emerg Infect Dis 21:184–186. doi: 10.3201/eid2101.141605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Midgley CM, EV-D68 Working Group, Watson JT, Nix WA, Curns AT, Rogers SL, Brown BA, Conover C, Dominguez SR, Feikin DR, Gray S, Hassan F, Hoferka S, Jackson MA, Johnson D, Leshem E, Miller L, Nichols JB, Nyquist AC, Obringer E, Patel A, Patel M, Rha B, Schneider E, Schuster JE, Selvarangan R, Seward JF, Turabelidze G, Oberste MS, Pallansch MA, Gerber SI. 2015. Severe respiratory illness associated with a nationwide outbreak of enterovirus D68 in the USA (2014): a descriptive epidemiological investigation. Lancet Respir Med 3:879–887. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00335-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao Q, Ren L, Zheng S, Wang L, Xie X, Deng Y, Zhao Y, Zhao X, Luo Z, Fu Z, Huang A, Liu E. 2015. Prevalence and molecular characterizations of enterovirus D68 among children with acute respiratory infection in China between 2012 and 2014. Sci Rep 5:16639. doi: 10.1038/srep16639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pellegrinelli L, Giardina F, Lunghi G, Uceda Renteria SC, Greco L, Fratini A, Galli C, Piralla A, Binda S, Pariani E, Baldanti F. 2019. Emergence of divergent enterovirus (EV) D68 sub-clade D1 strains, northern Italy, September to October 2018. Euro Surveill 24:1900090. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2018.24.7.1900090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bal A, Sabatier M, Wirth T, Coste-Burel M, Lazrek M, Stefic K, Brengel-Pesce K, Morfin F, Lina B, Schuffenecker I, Josset L. 2019. Emergence of enterovirus D68 clade D1, France, August to November 2018. Euro Surveill 24:1800699. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.3.1800699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen L, Gong C, Xiang Z, Zhang T, Li M, Li A, Luo M, Huang F. 2019. Upsurge of enterovirus D68 and circulation of the new subclade D3 and subclade B3 in Beijing, China, 2016. Sci Rep 9:6073. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42651-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hatchette TF, Drews SJ, Grudeski E, Booth T, Martineau C, Dust K, Garceau R, Gubbay J, Karnauchow T, Krajden M, Levett PN, Mazzulli T, McDonald RR, McNabb A, Mubareka S, Needle R, Petrich A, Richardson S, Rutherford C, Smieja M, Tellier R, Tipples G, LeBlanc JJ. 2015. Detection of enterovirus D68 in Canadian laboratories. J Clin Microbiol 53:1748–1751. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03686-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]