Enterobacter aerogenes was recently renamed Klebsiella aerogenes. This study aimed to identify differences in clinical characteristics, outcomes, and bacterial genetics among patients with K. aerogenes versus Enterobacter species bloodstream infections (BSI). We prospectively enrolled patients with K. aerogenes or Enterobacter cloacae complex (Ecc) BSI from 2002 to 2015.

KEYWORDS: Enterobacter cloacae complex, Gram-negative bacteremia, Klebsiella aerogenes, bloodstream infection

ABSTRACT

Enterobacter aerogenes was recently renamed Klebsiella aerogenes. This study aimed to identify differences in clinical characteristics, outcomes, and bacterial genetics among patients with K. aerogenes versus Enterobacter species bloodstream infections (BSI). We prospectively enrolled patients with K. aerogenes or Enterobacter cloacae complex (Ecc) BSI from 2002 to 2015. We performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and pan-genome analysis on all bacteria. Overall, 150 patients with K. aerogenes (46/150 [31%]) or Ecc (104/150 [69%]) BSI were enrolled. The two groups had similar baseline characteristics. Neither total in-hospital mortality (13/46 [28%] versus 22/104 [21%]; P = 0.3) nor attributable in-hospital mortality (9/46 [20%] versus 13/104 [12%]; P = 0.3) differed between patients with K. aerogenes versus Ecc BSI, respectively. However, poor clinical outcome (death before discharge, recurrent BSI, and/or BSI complication) was higher for K. aerogenes than Ecc BSI (32/46 [70%] versus 42/104 [40%]; P = 0.001). In a multivariable regression model, K. aerogenes BSI, relative to Ecc BSI, was predictive of poor clinical outcome (odds ratio 3.3; 95% confidence interval 1.4 to 8.1; P = 0.008). Pan-genome analysis revealed 983 genes in 323 genomic islands unique to K. aerogenes isolates, including putative virulence genes involved in iron acquisition (n = 67), fimbriae/pili/flagella production (n = 117), and metal homeostasis (n = 34). Antibiotic resistance was largely found in Ecc lineage 1, which had a higher rate of multidrug resistant phenotype (23/54 [43%]) relative to all other bacterial isolates (23/96 [24%]; P = 0.03). K. aerogenes BSI was associated with poor clinical outcomes relative to Ecc BSI. Putative virulence factors in K. aerogenes may account for these differences.

INTRODUCTION

The Enterobacterales family of Gram-negative bacteria were originally divided into three genera: Escherichia, Aerobacter, and Klebsiella, where the Aerobacter genus included A. aerogenes and A. cloacae (1). By 1960, Aerobacter had been redubbed Enterobacter (2). Recently, whole-genome sequence (WGS)-based comparative bacterial phylogenetics demonstrated that Enterobacter aerogenes is more closely related to Klebsiella pneumoniae than to the Enterobacter species (3). Hence, the bacteria formerly known as Enterobacter aerogenes was renamed Klebsiella aerogenes (4). The remaining members of the genus Enterobacter can be grouped into 22 distinct phylogenetic groups using average nucleotide identity (ANI) (3, 5). These 22 phylogenetic groups are together referred to as the Enterobacter cloacae complex (Ecc).

Though bacterial comparative genomics has demonstrated that K. aerogenes and Ecc belong to different phylogenetic groups, the clinical impact of these genetic differences is unknown. Differences in clinical risk factors, antibiotic susceptibility patterns, and patient outcomes have not yet been explored since renaming K. aerogenes. Further, it is unclear how genetic diversity within Ecc, which consists of 22 phylogenetic groups in and of itself, influences antibiotic resistance and clinical outcomes. These questions are relevant as we and others have shown that species-level differences in Gram-negative bacteria infections are associated with differences in clinical risk factors (6, 7), antibiotic susceptibility patterns (6, 8, 9), patient outcomes (6, 7, 10), and complications of infection (11). Better understanding of the clinical impact of different Gram-negative bacterial infections allows for more appropriate empirical antibiotic therapy, improved monitoring for infectious complications, and enhanced prognostic information.

The aims of this study were to identify how patients with K. aerogenes and Ecc bacteremia differ with respect to patient characteristics, patient outcomes, bacterial gene content, and antibiotic resistance phenotypes using prospectively collected clinical data and bacterial isolates from a biorepository at Duke University Medical Center from 2002 to 2015. Patient clinical data were retrospectively analyzed, and bacterial whole-genome sequencing and pan-genome analysis were performed.

(Portions of these results were previously presented as a poster at IDWeek, Washington DC, 2 to 6 October 2019 [12]).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population.

Patients in this study were identified from the Duke Bloodstream Infection Biorepository (BSIB), which is an ongoing and prospectively enrolled cohort of patients with monomicrobial Gram-negative bloodstream infection (BSI) at Duke University Medical Center. Informed consent is obtained, and from each enrolled patient detailed clinical data, bacterial isolate from blood culture, patient serum, and patient DNA are collected. In this study, we included patients with K. aerogenes or Ecc BSI from 2002 to 2015. If patients had multiple episodes of K. aerogenes or Ecc BSI, only the first such episode was included. Patients were also excluded for age of <18 years, polymicrobial BSI, or culture drawn in an outpatient setting.

Whole-genome sequencing and assembly.

Whole-genome sequencing was performed on the Enterobacterales isolates in collaboration with the J. Craig Venter Institute (JCVI). Genomic DNA was extracted with the Master Pure DNA purification kit (Epicentre) to construct paired-end libraries for whole-genome sequencing (Illumina HiSeq) with target coverage of 100×. HiSeq reads were assembled using Newbler, velvet, and Celera Assembler, and annotation was performed using NCBI’s Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (PGAP) (13).

Genetic analysis.

Pan-genome analysis was performed on the Enterobacterales isolates in collaboration with JCVI. Bioinformatics analyses, including generation of a phylogenetic tree and identification of antibiotic resistance genes, were performed through the JCVI pan-genome pipeline (14). The Pan-genome Ortholog Clustering Tool (PanOCT) was used to identify flexible genomic islands associated with K. aerogenes versus Ecc and patient-attributable mortality (14, 15). The PanOCT algorithm compared gene content using default parameters except that the minimum percent identity was set to 70%. PanOCT first determines the core genes which are present in almost all of the isolates included in the pan-genome (in this case both the K. aerogenes and Ecc isolates) and then determines “flexible genomic islands” (fgi) (16) that are inserted between core genes. These flexible genomic islands and the genes they contain can then be queried for those that are differentially present in K. aerogenes and Ecc BSI isolates.

Definitions.

The BSI outcome was defined as one of four possible endpoints: (i) cure: no evidence of recurrent infection within the hospital admission; (ii) recurrence: clinical resolution of the initial episode of infection after treatment but culture-confirmed BSI with the same organism documented within the hospital admission; (iii) attributable mortality: persistent signs or symptoms of infection, positive blood cultures, or a persistent focus of infection at the time of death in the absence of another explanation for death; or (iv) death due to underlying causes: deemed not to be due to K. aerogenes or Ecc BSI by evaluation of one of the investigators (J.T.T.). Complications, including septic shock, acute kidney injury (AKI), acute lung injury (ALI) or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), or shock liver were defined per standard guidelines (17–21). Poor clinical outcome was defined as the presence of ≥1 of the following: death prior to discharge, recurrent BSI, and/or complication of BSI. The multidrug resistant (MDR), extensively drug-resistant (XDR), and pandrug resistant (PDR) phenotypes were defined per standard guidelines: MDR as resistance to at least one drug in ≥3 relevant classes, XDR as resistance to at least one drug in all but ≤2 relevant classes, and PDR as resistance to all relevant drugs (22). Additional definitions may be found in the supplemental material.

Statistical analysis.

Baseline characteristics and clinical events are presented as either means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges for continuous variables and frequencies with proportions for categorical variables. Statistical comparisons between groups for continuous variables were made with the Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s t test. For categorical variables, comparisons were made using Fisher’s exact test. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to determine risk factors associated with total in-hospital mortality, attributable mortality, and poor clinical outcome. Covariates in the multivariable logistic regression model included BSI species, age, race, gender, route of BSI (i.e., community- versus hospital-acquired), source of BSI (e.g., genitourinary tract), days to effective antibiotic therapy, and chronic APACHE-II score. Antibiotic resistance genes were compared using Fisher’s exact test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Analyses were done using Stata 16.0.

Data availability. All of the genomes determined in this study are available at NCBI under BioProject no. PRJNA259658.

RESULTS

Patient demographics.

There were 150 patients with K. aerogenes (46/150 [31%]) or Ecc (104/150 [69%]) BSI enrolled over the study period. The clinical characteristics of patients with K. aerogenes versus Ecc BSI were similar (Table 1). Patients with Ecc BSI were more commonly hemodialysis-dependent (24/104 [23%]) compared to those with K. aerogenes BSI (4/46 [9%]; P = 0.04). Otherwise, there were no significant differences between patients with K. aerogenes versus Ecc BSI for rates of other clinical characteristics.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of patients with K. aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae complex (Ecc) bloodstream infections at Duke University from 2002 to 2015a

| Clinical characteristics | K. aerogenes (n = 46) | Ecc (n = 104) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 65 (59, 71) | 57 (51, 68.5) | 0.1 |

| No. by race (%) | |||

| White | 28 (61) | 72 (69) | 0.2 |

| Black | 14 (30) | 30 (29) | |

| Other/unknown | 4 (9) | 2 (2) | |

| No. female gender (%) | 10 (22) | 37 (36) | 0.1 |

| No. with past medical history (%) | |||

| Recent glucocorticoid use | 12 (26) | 19 (18) | 0.3 |

| Neoplasm | 18 (39) | 42 (40) | 1.0 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 15 (33) | 38 (37) | 0.7 |

| Transplant | 5 (11) | 12 (12) | 1.0 |

| Surgery in past 30 days | 14 (30) | 44 (42) | 0.2 |

| Hemodialysis dependence | 4 (9) | 24 (23) | 0.04 |

| Rheumatologic disorder | 1 (2) | 3 (3) | 1.0 |

| No. by site of acquisition (%) | |||

| Community-acquired | 21 (46) | 57 (55) | 0.4 |

| Hospital-acquired | 25 (54) | 47 (45) | |

| No. by source of infection (%) | |||

| Urine/pyelonephritis | 7 (15) | 16 (16) | 0.1 |

| Pneumonia | 4 (9) | 4 (4) | |

| Abscess | 5 (11) | 7 (7) | |

| Line-associated | 5 (11) | 28 (27) | |

| Skin/soft tissue | 0 (0) | 7 (7) | |

| Biliary tract | 5 (11) | 6 (6) | |

| Other | 6 (13) | 8 (8) | |

| Source not identified | 14 (30) | 28 (27) | |

| Mean days to appropriate antibiotic therapy (SD) | 0.8 (1.2) | 0.7 (1.0) | 0.4 |

| No. with appropriate antibiotics on day 0 (%) | 26 (57) | 62 (60) | 0.2 |

| No. with appropriate antibiotics after day 0 (%) | 19 (41) | 41 (39) | |

| APACHE-II acute physiology score, mean (SD) | 8.6 (6.5) | 7.1 (4.4) | 0.1 |

| APACHE-II chronic illness score, mean (SD) | 3.9 (2.1) | 3.8 (2.1) | 0.8 |

| No. with score of 0 (%) | 10 (22) | 25 (24) | 0.8 |

| No. with score of 5 (%) | 36 (78) | 79 (76) | |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; Ecc, Enterobacter cloacae complex.

Clinical outcomes.

The overall rates of total and attributable (i.e., due to the BSI) in-hospital mortality were 23% (35/150) and 15% (22/150), respectively. Neither total in-hospital mortality (28% versus 21%, P = 0.4) nor attributable in-hospital mortality (20% versus 12%, P = 0.3) differed significantly between patients with K. aerogenes and Ecc BSI, respectively (Table 2). The PanOCT algorithm did not identify any flexible genomic islands associated with increased total or attributable in-hospital mortality in patients with K. aerogenes or Ecc BSI. The overall rate of poor clinical outcome was 49% (74/150). Poor clinical outcome was more common in patients with K. aerogenes BSI than Ecc BSI (70% versus 40%, P = 0.001). The rates of all individual BSI complications were higher in K. aerogenes versus Ecc BSI, though only acute kidney injury was statistically significant (43% versus 21%, P = 0.01). By definition, patients on hemodialysis cannot have the complication of acute kidney injury. However, even when these 28 patients were excluded, those with K. aerogenes BSI had increased rate of poor clinical outcomes (P = 0.01). No bacterial clade was associated with poor clinical outcome (Ecc, P = 0.2; K. aerogenes P = 0.6). Clinical outcomes associated with the Ecc clades are shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 2.

Outcomes of patients with K. aerogenes versus Enterobacter cloacae complex (Ecc) bloodstream infections

| Outcomes | K. aerogenes (n = 46) | Ecc (n = 104) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. total in-hospital mortality (%) | 13 (28) | 22 (21) | 0.4 |

| No. with attributable mortality (%) | 9 (20) | 13 (12) | 0.3 |

| No. recurrent bloodstream infection (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 1.0 |

| No. complications (%) | |||

| Septic shock | 14 (30) | 22 (21) | 0.2 |

| Acute kidney injury | 20 (43) | 22 (21) | 0.01 |

| Acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome | 4 (9) | 6 (6) | 0.5 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | 0.2 |

| Shock liver | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | 1.0 |

| No. with poor clinical outcome (%)a | 32 (70) | 42 (40) | 0.001 |

Poor clinical outcomes indicates ≥1 of the following: death prior to discharge, recurrent bloodstream infection, or complication of bloodstream infection.

Multivariable logistic regression models for total in-hospital mortality, attributable mortality, and poor clinical outcome were generated (Table 3). Bacterial species (i.e., K. aerogenes versus Ecc) was not associated with either total in-hospital mortality (odds ratio [OR] 1.2, 95% CI 0.4 to 3.0, P = 0.8) or attributable mortality (OR 1.5, 95% CI 0.4 to 5.1, P = 0.5). In the multivariable logistic regression model of poor clinical outcome, however, K. aerogenes was associated with increased poor outcome (OR 3.3, 95% CI 1.4 to 8.1, P = 0.008).

TABLE 3.

Multivariable logistic regression models for total in-hospital mortality, attributable in-hospital mortality, and poor clinical outcome in patients with K. aerogenes and E. cloacae complex bloodstream infectione Predictors with P < 0.05 are in bold

| Predictor | Total mortality (OR [95% CI]) (P value) | Attributable mortality (OR [95% CI]) (P value) | Poor clinical outcome (OR [95% CI]) (P value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| K. aerogenes | 1.2 [0.4, 3.0] (0.8) | 1.5 [0.4, 5.1] (0.5) | 3.3 [1.4, 8.1] (0.008) |

| Age | [1.0, 1.1] (0.05) | 1.1 [1.0, 1.1] (0.01) | 1.0 [1.0, 1.1] (0.04) |

| Racea | 0.7 [0.2, 1.8] (0.4) | 0.3 [0.1, 1.2] (0.09) | 0.7 [0.3, 1.6] (0.4) |

| Female gender | 1.4 [0.5, 4.4] (0.5) | 2.0 [0.5, 9.0] (0.3) | 0.8 [0.3, 1.9] (0.6) |

| Hospital-acquired | 1.1 [0.4, 3.0] (0.9) | 2.6 [0.7, 9.8] (0.2) | 1.8 [0.8, 4.3] (0.2) |

| Infection sourceb | |||

| Pneumonia | 2.5 [0.2, 26.8] (0.4) | 5.2 [0.2, 124.1] (0.3) | 0.4 [0.05, 3.2] (0.4) |

| Abscessc | 0.8 [0.1, 9.9] (0.8) | 0.2 [0.03, 1.0] (0.05) | |

| Line | 0.6 [0.1, 4.1] (0.6) | 2.5 [0.2, 36.5] (0.5) | 0.1 [0.03, 0.4] (0.002) |

| Skind | 0.6 [0.1, 3.9] (0.6) | ||

| Biliary | 1.7 [0.2, 13.5] (0.6) | 7.3 [0.4, 119.5] (0.2) | 0.4 [0.1, 1.9] (0.2) |

| Other | 8.9 [1.4, 57.3] (0.02) | 30.4 [2.0, 471.4] (0.02) | 0.9 [0.2, 4.6] (0.9) |

| Unknown | 6.4 [1.4, 29.8] (0.02) | 8.1 [0.8, 88.4] (0.08) | 0.6 [0.2, 2.0] (0.4) |

| Antibiotics after day 0 | 1.2 [0.4, 3.1] (0.7) | 0.6 [0.2, 2.2] (0.5) | 0.7 [0.3, 1.6] (0.4) |

| Chronic APACHE-II of 5 | 3.1 [1.0, 9.8] (0.06) | 4.3 [0.9, 22.0] (0.08) | 1.6 [0.01, 1.8] (0.1) |

Race analyzed as binary (white versus nonwhite).

Reference is patients with genitourinary source of infection.

Abscess source not included in attributable mortality model due to the small number of cases and events.

Skin source not included in total mortality and attributable mortality models due to the small number of cases and events.

Predictors with P < 0.05 are in bold; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Bacterial phylogeny.

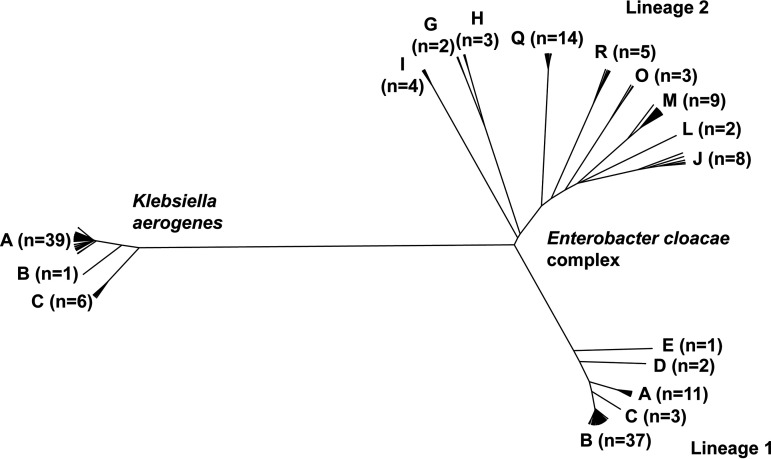

Prior work demonstrated that there are 22 known Ecc clades (3). The 104 Ecc BSI isolates included in this study encompassed 14 (64%) of these clades (Fig. 1). More broadly, the Ecc BSI isolates could be grouped into two lineages, with one lineage encompassing Ecc clades A to E and the other encompassing clades G to J, L to M, O, and Q to R (Fig. 1). To our knowledge, K. aerogenes has no prior clade designations. Using an average nucleotide identify approach, we identified three K. aerogenes clades, labeled A to C (Fig. 1). The K. aerogenes BSI isolates were primarily in the designated A clade (39/45 [87%]).

FIG 1.

Phylogenetic tree of K. aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae complex isolates with clade designations. The number of bacterial isolates in each clade are listed.

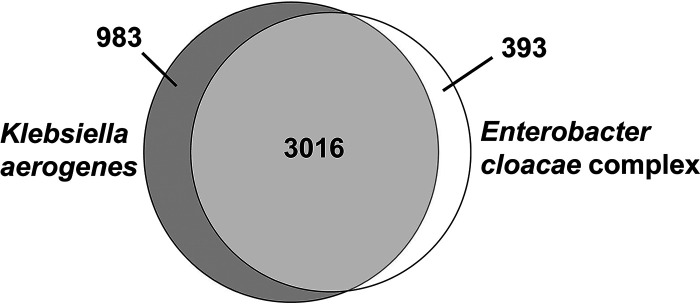

The PanOCT algorithm was used to identify the specific genetic islands that distinguish K. aerogenes from the Ecc BSI isolates. The total number of genes was 4,392, with 3,016 (69%) shared between K. aerogenes and Ecc, 983 (22%) unique to K. aerogenes, and 393 (9%) unique to Ecc (Fig. 2). By unique to a given group, we mean that 90% or more of the isolates of that group contained the gene while 10% or fewer of isolates of the other group contained the same gene. We identified 323 flexible genetic islands specific to K. aerogenes, and 191 specific to Ecc. Close inspection of genes unique to K. aerogenes revealed multiple genes with putative functions in cellular processes that are often associated with bacterial virulence (Table S2), including iron acquisition (8 fgi with 67 total genes), fimbriae/pili attachment (8 fgi with 106 total genes), flagella movement and attachment (5 fgi with 11 total genes), and metal homeostasis (4 fgi with 34 total genes).

FIG 2.

Venn diagram of genes shared and specific to Klebsiella aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae complex in bloodstream infection isolates.

Antibiotic resistance.

The rates of K. aerogenes and Ecc resistance to individual antibiotics are listed in Table S3. Rates of resistance to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (19% versus 0%, P < 0.001) and gentamicin (10% versus 0%, P = 0.03) were higher in Ecc isolates relative to K. aerogenes. The MDR phenotype was similar between Ecc and K. aerogenes (30% versus 33%, P = 0.8). Only Ecc had XDR isolates (3/104 [3%] versus 0/46 [0%]; P = 0.6). No PDR isolates were identified.

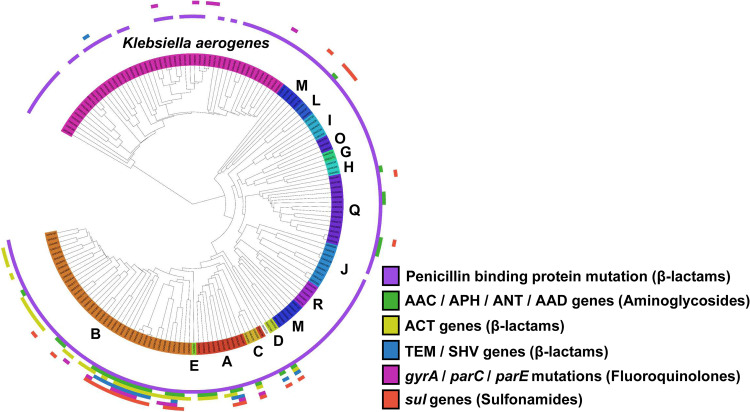

In order to determine the mechanisms by which K. aerogenes and Ecc develop resistance to antibiotics, we used whole-genome sequencing to identify antibiotic resistance genes and antibiotic resistance mutations present in each bacterial isolate (Fig. 3). Penicillin binding protein 3 (PBP3) was the most commonly present resistance gene, found in 94% (141/150) of K. aerogenes and Ecc isolates. PBP3 is an essential protein that catalyzes cross-linking of the peptidoglycan wall, though the variant in this study is homologous to PBP3 in Haemophilus influenzae, where it has been implicated in resistance to β-lactam antibiotics.

FIG 3.

Phylogenetic tree of K. aerogenes and E. cloacae complex (Ecc) with the presence of antibiotic resistance genes per strain. The colors in the inner ring indicate the different Ecc clades (labeled A to E, G to J, L to M, O, Q to R) and K. aerogenes (all clades same color). Antibiotic resistance genes in each strain are indicated by bars in the outer concentric rings. The identified antibiotic resistance genes are noted in the key.

Figure 3 illustrates increased acquisition of antibiotic genes within Ecc lineage 1 (i.e., clades A to E), which corresponds to species E. hormaechei (clades A to E) (3). Ecc lineage 1 was associated with the MDR phenotype (23/54 [43%]) relative to Ecc lineage 2 (8/50 [16%]; P = 0.005) and to all other non-Ecc lineage 1 bacterial isolates in this study (23/96 [24%]; P = 0.03). The MDR phenotype in Ecc lineage 1 was driven by the acquisition of multiple antibiotic resistance genes, including the AAC/APH/ANT/AAD aminoglycoside resistance genes (22/54 [41%]), ACT β-lactam resistance genes (33/54 [61%]), TEM/SHV genes that confer the extended-spectrum β-lactamase phenotype (12/54 [22%]), gyrA/parC/parE fluroquinolone resistance genes (13/54 [24%]), and sul genes that confer resistance to sulfonamides (18/54 [33%]) (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to understand differences between K. aerogenes and Ecc BSI with respect to patient demographics, clinical outcomes, bacterial phylogenetics, and antibiotic susceptibility patterns. To our knowledge, it is the first study to examine such differences in the two patient populations. It revealed three major findings.

First, the clinical characteristics of patients with K. aerogenes versus Ecc BSI were similar. Hemodialysis dependence was the only identified risk factor for Ecc BSI. Though no prior studies have addressed the risk factors for BSI with K. aerogenes (or Enterobacter aerogenes, as it was previously named) versus Ecc BSI, a large recent study did find that hemodialysis dependence was an independent risk factor for Enterobacter species BSI relative to noninfected control patients (23).

Second, we found that poor clinical outcome was significantly more common in patients with K. aerogenes versus Ecc BSI. Poor clinical outcome is a collapsed variable that is defined as present when the patient either dies prior to hospital discharge, has recurrent infection, or experiences a complication of the BSI. A remarkable 70% of patients with K. aerogenes BSI had poor clinical outcome. Patients with K. aerogenes BSI had numerically higher rates of almost all the individual components that define this variable. However, of these individual components, only the rate of AKI was statistically significant between the two groups. Understanding why patients with K. aerogenes BSI had an increased rate of AKI is complicated by the fact that sepsis-induced AKI may occur through diverse mechanisms. Sepsis-induced AKI is generally thought to stem from global renal ischemia, cellular damage, and acute tubular necrosis (24). However, there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that it may occur even in the absence of hypoperfusion. For example, cytokine levels (e.g., IL-6 and IL-10) and oxidative stress have been shown to also play roles in sepsis-induced AKI (25–27). While it is not clear why K. aerogenes was associated with increased AKI, it is tempting to speculate that the multiple additional iron acquisition genes may be playing a role, as bacterial proliferation has been shown to be supplemented by iron sufficiency and suppressed by iron restriction (28, 29). Further, elevated serum iron levels have been associated with increased mortality in patients with sepsis (30).

Third, we found that antibiotic resistance was driven in large part by the acquisition of resistance genes in Ecc lineage 1, which encompasses clades A to E. This lineage is E. hormaechei (clades A to E). Ecc lineage 1 had significantly higher antibiotic resistance relative to either Ecc lineage 2 or all other non-Ecc lineage 1 isolates included in this study. As shown in Fig. 3, this increased resistance stemmed from acquisition of multiple genes that are active against aminoglycosides (AAC, APH, ANT, and AAD), β-lactams (ACT, TEM, and SHV), fluoroquinolones (parC, parE, and gyrA), and sulfonamides (sul genes). The only XDR isolates (n = 3) in this study were in Ecc lineage 1.

This study has several limitations. First, it involved only a single health system. However, given that we enrolled a relatively large number of patients over a 14 year period, we believe that our results are generalizable. Second, detailed management decisions were not available for each patient to compare how treatment may have affected clinical outcomes. However, we have included data involving timing of appropriate antibiotic therapy, which is one of the most critical factors in sepsis outcomes.

In summary, the bacteria formerly known as Enterobacter aerogenes was recently renamed Klebsiella aerogenes on the basis of whole-genome sequence-based phylogenetics. The clinical and bacterial virulence gene differences between K. aerogenes and the remaining Enterobacter isolates had not been studied prior to this work. Here, we found that the clinical characteristics of patients in the two groups were quite similar, though the clinical outcomes differed substantially. K. aerogenes BSI was associated with increased poor clinical outcome relative to Ecc BSI. The etiology behind this difference is unknown, though could be related to the multiple putative virulence genes (e.g., iron acquisition, flagella production, fimbriae production, and/or metal homeostasis) that were specifically identified in the K. aerogenes isolates.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author contributions included conception and design (A.W., G.S., D.E.F., V.G.F., J.T.T.), acquisition of data (F.R., V.G.F., J.T.T.), analysis and interpretation of data (A.W., G.S., D.E.F., L.P.P., V.G.F., J.T.T.), and manuscript preparation (A.W., G.S., F.R., L.P.P., D.E.F., V.G.F., J.T.T.).

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number 1KL2TR002554 (to J.T.T.) and NIH K24-AI093969 (to V.G.F). It was also supported in part by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the NIH and Department of Health and Human Services under award number U19AI110819 to the J. Craig Venter Institute (G.S. and D.E.F.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brooke MS. 1953. The differentiation of Aerobacter aerogenes and Aerobacter cloacae. J Bacteriol 66:721–726. doi: 10.1128/JB.66.6.721-726.1953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davin-Regli A, Pagès JM. 2015. Enterobacter aerogenes and Enterobacter cloacae; versatile bacterial pathogens confronting antibiotic treatment. Front Microbiol 6:392. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chavda KD, Chen L, Fouts DE, Sutton G, Brinkac L, Jenkins SG, Bonomo RA, Adams MD, Kreiswirth BN. 2016. Comprehensive genome analysis of carbapenemase-Pproducing Enterobacter spp.: new insights into phylogeny, population structure, and resistance mechanisms. mBio 7:e02093-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02093-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tindall BJ, Sutton G, Garrity GM. 2017. Enterobacter aerogenes Hormaeche and Edwards 1960 (Approved Lists 1980) and Klebsiella mobilis Bascomb et al. 1971 (Approved Lists 1980) share the same nomenclatural type (ATCC 13048) on the 4 Approved Lists and are homotypic synonyms, with consequences for the name Klebsiella mobilis Bascomb et al. 1971 (Approved Lists 1980.). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 67:502–504. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sutton GG, Brinkac LM, Clarke TH, Fouts DE. 2018. Enterobacter hormaechei subsp. hoffmannii subsp. nov., Enterobacter hormaechei subsp. xiangfangensis comb. nov., Enterobacter roggenkampii sp. nov., and Enterobacter muelleri is a later heterotypic synonym of Enterobacter asburiae based on computational analysis of sequenced Enterobacter genomes. F1000Res 7:521. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14566.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thaden JT, Park LP, Maskarinec SA, Ruffin F, Fowler VG Jr, van Duin D. 2017. Results from a 13-year prospective cohort study show increased mortality associated with bloodstream infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa compared to other bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 61:e02671-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02671-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambert ML, Suetens C, Savey A, Palomar M, Hiesmayr M, Morales I, Agodi A, Frank U, Mertens K, Schumacher M, Wolkewitz M. 2011. Clinical outcomes of health-care-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance in patients admitted to European intensive-care units: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 11:30–38. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thaden JT, Fowler VG, Sexton DJ, Anderson DJ. 2016. Increasing incidence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in community hospitals throughout the southeastern United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37:49–54. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiner LM, Webb AK, Limbago B, Dudeck MA, Patel J, Kallen AJ, Edwards JR, Sievert DM. 2016. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the national healthcare safety network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011–2014. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 37:1288–1301. doi: 10.1017/ice.2016.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ani C, Farshidpanah S, Bellinghausen Stewart A, Nguyen HB. 2015. Variations in organism-specific severe sepsis mortality in the United States: 1999–2008. Crit Care Med 43:65–77. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maskarinec SA, Thaden JT, Cyr DD, Ruffin F, Souli M, Fowler VG. 2017. The risk of cardiac device-related infection in bacteremic patients is species specific: results of a 12-year prospective cohort. Open Forum Infect Dis 4:ofx132. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofx132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wesevich A, Sutton G, Fouts D, Fowler VG Jr, Thaden JT. 2019. Newly-named Klebsiella aerogenes is associated with poor clinical outcomes relative to Enterobacter cloacae complex in patients with bloodstream infection. IDWeek 2019, Washington DC, USA, 2 to 6 October 2019, poster 221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tatusova T, DiCuccio M, Badretdin A, Chetvernin V, Nawrocki EP, Zaslavsky L, Lomsadze A, Pruitt KD, Borodovsky M, Ostell J. 2016. NCBI prokaryotic genome annotation pipeline. Nucleic Acids Res 44:6614–6624. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inman JM, Sutton GG, Beck E, Brinkac LM, Clarke TH, Fouts DE. 2019. Large-scale comparative analysis of microbial pan-genomes using PanOCT. Bioinformatics 35:1049–1050. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouts DE, Brinkac L, Beck E, Inman J, Sutton G. 2012. PanOCT: automated clustering of orthologs using conserved gene neighborhood for pan-genomic analysis of bacterial strains and closely related species. Nucleic Acids Res 40:e172. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan AP, Sutton G, DePew J, Krishnakumar R, Choi Y, Huang XZ, Beck E, Harkins DM, Kim M, Lesho EP, Nikolich MP, Fouts DE. 2015. A novel method of consensus pan-chromosome assembly and large-scale comparative analysis reveal the highly flexible pan-genome of Acinetobacter baumannii. Genome Biol 16:143. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0701-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy MM, Rhodes A, Phillips GS, Townsend SR, Schorr CA, Beale R, Osborn T, Lemeshow S, Chiche JD, Artigas A, Dellinger RP. 2015. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: association between performance metrics and outcomes in a 7.5-year study. Crit Care Med 43:3–12. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ragaller M, Richter T. 2010. Acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Emerg Trauma Shock 3:43–51. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.58663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, Levin A, Acute Kidney Injury Network. 2007. Acute Kidney Injury Network: report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care 11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, Watson HG. 2009. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Br J Haematol 145:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeto RK, Fenn B, Rockey DC. 2000. Ischemic hepatitis: clinical presentation and pathogenesis. Am J Med 109:109–113. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00461-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Magiorakos AP, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, Carmeli Y, Falagas ME, Giske CG, Harbarth S, Hindler JF, Kahlmeter G, Olsson-Liljequist B, Paterson DL, Rice LB, Stelling J, Struelens MJ, Vatopoulos A, Weber JT, Monnet DL. 2012. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:268–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Álvarez-Marín R, Navarro-Amuedo D, Gasch-Blasi O, Rodríguez-Martínez JM, Calvo-Montes J, Lara-Contreras R, Lepe-Jiménez JA, Tubau-Quintano F, Cano-García ME, Rodríguez-López F, Rodríguez-Baño J, Pujol-Rojo M, Torre-Cisneros J, Martínez-Martínez L, Pascual-Hernández Á, Jiménez-Mejías ME, Spanish Network for Research in Infectious Diseases/Enterobacter spp. Bacteriemia Project g. 2020. A prospective, multicenter case control study of risk factors for acquisition and mortality in Enterobacter species bacteremia. J Infect 80:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarbock A, Gomez H, Kellum JA. 2014. Sepsis-induced acute kidney injury revisited: pathophysiology, prevention and future therapies. Curr Opin Crit Care 20:588–595. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0000000000000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murugan R, Karajala-Subramanyam V, Lee M, Yende S, Kong L, Carter M, Angus DC, Kellum JA, Genetic, Inflammatory Markers of Sepsis I. 2010. Acute kidney injury in non-severe pneumonia is associated with an increased immune response and lower survival. Kidney Int 77:527–535. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Payen D, Lukaszewicz AC, Legrand M, Gayat E, Faivre V, Megarbane B, Azoulay E, Fieux F, Charron D, Loiseau P, Busson M. 2012. A multicentre study of acute kidney injury in severe sepsis and septic shock: association with inflammatory phenotype and HLA genotype. PLoS One 7:e35838. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu L, Gokden N, Mayeux PR. 2007. Evidence for the role of reactive nitrogen species in polymicrobial sepsis-induced renal peritubular capillary dysfunction and tubular injury. JASN 18:1807–1815. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freidank HM, Billing H, Wiedmann-Al-Ahmad M. 2001. Influence of iron restriction on Chlamydia pneumoniae and C. trachomatis. J Med Microbiol 50:223–227. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-3-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh PF, Lin TL, Lee CZ, Tsai SF, Wang JT. 2008. Serum-induced iron-acquisition systems and TonB contribute to virulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae causing primary pyogenic liver abscess. J Infect Dis 197:1717–1727. doi: 10.1086/588383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lan P, Pan KH, Wang SJ, Shi QC, Yu YX, Fu Y, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Hua XT, Zhou JC, Yu YS. 2018. High serum iron level is associated with increased mortality in patients with sepsis. Sci Rep 8:11072. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29353-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.